Abstract

Background

Today, itching is understood as an independent sensory perception, which is based on a complex etiology of a disturbed neuronal activity and leads to clinical symptoms. The primary afferents (pruriceptors) have functional overlaps with afferents of thermoregulation (thermoceptors). Thus, an antipruritic effect can be caused by antagonizing heat‐sensitive receptors of the skin. The ion channel TRP‐subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) is of particular importance in this context. Repeated heat application can induce irreversible inactivation by unfolding of the protein, causing a persistent functional deficit and thus clinically and therapeutically reducing itch sensation.

Material and methods

To demonstrate relevant heat diffusion after local application of heat (45°C to 52°C for 3 and 5 seconds) by a technical medical device, the temperature profile for the relevant skin layer was recorded synchronously on ex vivo human skin using an infrared microscope.

Results

The results showed that the necessary activation temperature for TRPV1 of (≥43°C) in the upper relevant skin layers was safely reached after 3 and 5 seconds of application time. There were no indications of undesirable thermal effects.

Conclusion

The test results show that the objectified performance of the investigated medical device can be expected to provide the necessary temperature input for the activation of heat‐sensitive receptors in the skin. Clinical studies are necessary to prove therapeutic efficacy in the indication pruritus.

Keywords: concentrated heat, itch, local hyperthermia, pruritus, TRPV1

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic pruritus is a subjectively felt clinical symptom caused by an independent sensory perception due to a complex etiology of a disturbed neuronal activity. 1 In this process, the neurosensory signal is conducted by primary afferent fibers (pruriceptors) from the skin via the spinal cord to the brain. 2 , 3 These pseudounipolar and polymodal pruriceptors are divided according to biophysical criteria into thin myelinated A (diameter 2–5 μm, conduction velocity < 8 m/s) and unmyelinated C fibers (diameter 0.2–1.5 μm, conduction velocity < 2 m/s). 4 , 5 They are integrated into an interactive milieu that is regulated and determined by molecular (e.g., cytokines, ion channels), chemical (e.g., pH), physical (e.g., temperature, tissue tension), and cellular (e.g., lymphocytes, macrophages) environmental conditions. 6 , 7 , 8 Of particular interest is the influence of pruriceptors and thermosensitive nociceptors on sensory neurons (thermoceptors). The latter include both cold (activity <35°C) and heat (activity >25°C/>35°C) receptors. 9 , 10 , 11 The functional overlap of these nociceptive systems allows specific manipulation of the activation behavior of the pruriceptors by activating the thermoceptors. 12 Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) proteins, which are particularly, but not exclusively, expressed on the surface of sensory neurons, are of primary importance as thermosensitive nociceptors. TRPs control the passage of ions across the cell membrane in both cold‐ and heat‐regulated ways. In the present context, heat‐dependent nociceptors are of particular interest, with a threshold temperature at the field skin of approximately 34°C–42°C. 11

TRP‐subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) is a very well‐studied ion channel that multimodally converts cellular signals into membrane depolarization and causes an increase in intracellular calcium. 11 , 13 , 14 It is expressed in high density on peripheral sensory neurons and is directly related to pain perception. 15 Its activation occurs by temperatures >42°C–43°C, a low pH environment, or by chemical ligands containing a vanilloid group, such as capsaicin, by proton transfer of small‐molecule lipophilic substances such as anandamide, a cannabinoid lipid, and other agonists. 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 Other thermoceptors such as TRPV3 (activity between 30°C and 33°C), the potassium channels TRAAK and TREK‐1 as well as voltage‐gated K+ channel ß2 (KVß2) have a subordinate function. 19 , 20 , 21 The particular importance of TRPV1, apart from nociception of pain, lies mainly in mediating IL‐31‐ or histamine‐induced itch. 22 , 23 In addition, TRPV1 initiates itch perception through TRPV4 and is functionally involved in mediating neurogenic inflammatory processes. 24 , 25

Against this background, antagonization of TRPV1 with the aim of analgesic, antipruritic, but also anti‐inflammatory effects are obvious. 14 , 26 A variety of approaches using small‐molecule antagonists and therapeutic antibodies can be found in the literature, predominantly in animal models, but some in humans. 27 However, these pharmacological approaches have limitations because of the ubiquitous expression of TRPV1 and the associated potential risks of systemic application.

For dermatological indications, especially for antipruritic therapy, the epicutaneous application of formulations with small‐molecule antagonists is an option, although these have not yet been developed to market approval. Another possibility of antagonizing TRPV1 arises from the observation that locally applied hyperthermia leads to a sustained local reduction of pain and itching. 28 , 29 This can be explained by the fact that repeated activation of TRPV1 by thermal pulses above 41°C–43°C leads to partial or complete unfolding of the channel protein and thus to its irreversible inactivation. 30 , 31 The heat input necessary for this effect is provided by a technical medical device that normally applies thermal pulses of ∼51° but can be modified to apply thermal pulses of 45°C–52°C for 3 or 5 s. 32 In particular, the thermal conductivity of the upper skin layers within the epithelium, rather than thermal convection or thermal radiation, results in thermal energy input into the relevant skin layers. 33 , 34 Since the skin is a complex tissue and its thermal conductivity ultimately corresponds to the cumulative properties of all its components, the actual thermal input could previously only be estimated. The present investigations were intended to determine the heat input over time specifically for the individual skin layers by means of a realistic experimental set‐up using infrared microscopic measurements on ex vivo human skin.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Camera system

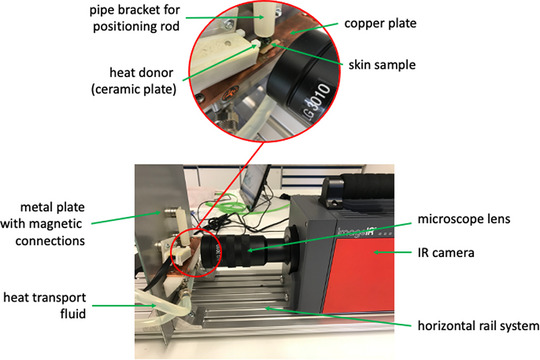

The thermography system ImageIR® 7380 (InfraTec GmbH, Dresden, Germany) was used for the investigations. This is a high‐resolution IR camera with a full frame frequency of 75 Hz, a resolution of 640 × 512 infrared pixels and a measurement accuracy of ±1%. For the measurement, a precision microscope lens LG3010 (M = 3.0×) from the same manufacturer was used for a working distance of 22 mm (Figure 1). The camera system was built by the manufacturer (InfraTec GmbH, Dresden, Germany) and calibrated before use. The data recording and evaluation of the thermography images were carried out using the software IRBIS® 3.1.84 professional (InfraTec GmbH, Dresden, Germany). The raw data were exported into MS Excel format and processed for graphical display.

FIGURE 1.

Experimental setup of the measuring track with representation of the individual components

2.2. Medical device

All measurements were conducted with standard “bite away” electronics (Mibetec GmbH, Sandersdorf‐Brehna, Germany). The marketed version is configurated with a temperature/time interval of ∼51°C for 3 or 5 s. The changes of the configuration of the control parameters, in detail the treatment temperature and time, were done via a programming adapter. 35 The programming adapter enabled a communication between the bite away electronics and a PC system. To modify the relevant treatment parameters a control software MessPC® Win (NetWays GmbH, Nürnberg, Deutschland) was used that could also initiate the treatment start. The remotely initialized start of the treatment was important to avoid interferences by the body heat of an operator. As a protection of the electronics a 3D‐printed housing was used. A magnetic mounting system made it possible to mount the housing on a carrier plate as well as to adjust the electronics and the skin samples.

2.3. Experimental design

The investigations were performed on freshly excised ex vivo mammary skin (Biopredic International, Saint Grégoire, France). The tissue sections were postoperatively cleaned with mull pads and isotonic NaCl solution. The subcutaneous adipose tissue was mechanically dissected and discarded. Circular pieces of skin (20 mm in diameter) were punched, hermetically sealed in tin foil, packed in an occlusive polyethylene bag, and stored at −20°C for 2–3 weeks. At the time of the investigation, the pieces of skin were completely defrosted at room temperature and the surface was dried using cotton pads. After a visual examination for physical damage the pieces of skin were allowed to equilibrate in the holding device and to hydrate. Afterward a prestudy integrity evaluation of skin pieces was carrying out. For evaluating the hydration of the horny layer as a measure of the barrier function, the capacity above the skin surface was measured by means of a corneometer (Courage and Khazaka Electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany) and under standardized conditions. The corneometer has a measuring depth of about 30 μm. Grid‐shaped metal sheets that are isolated against each other within the measuring probe, taking the effect of a condensator, enable the measurement of changes in the capacity according to the water content as nondimensional values at the test areas. The external conditions of measurement were ensured in compliance with the EEMCO‐Guidelines. The integrity was found out when the corneometer value was in the range of 25th−75th percentile of the values (46–57 AU) of a blank population.

The test device consisted of a horizontal rail system on which the camera with the microscope lens was installed. In the direction of the camera optics, a metal plate was fixed at the end of the rail system at an angle of 90°. On this plate, both the holder for both the medical device and for the skin sample could be continuously placed via magnetic connections. Before positioning it on a copper tempering plate at the bottom, the skin was thinly moistened with a pure hydrogel (Raya Hyaluronic Acid Gel, density 1015 cm3, ExperChem Ltd., Weinheim, Germany) to ensure better heat coupling to reduce the skin temperature to 32°C (body surface temperature). The copper plate was tempered to exactly 32°C (±0.2°C) by a circulation thermostat (PT31, Krüss GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) with a heat transport fluid (mixture of water and glycol). In order to standardize the contact pressure of the temperature‐giving ceramic plate of the medical device, a positioning rod was guided over a pipe bracket exactly over the ceramic plate. The positioning rod had a net weight of 4.0 g.

Figure 1 pictures the test setup graphically. It shows the horizontal examination process in which the IR microscope focuses the human skin on the outer, straight edge and thus detects all layers. The ceramic heating plate of the medical device is placed on the skin surface, so that changes in temperature in the respective skin layers can be measured synchronously. Due to the control electronics, the temperature transfer from the ceramic heating plate to the skin as well as the temperature distribution within the skin layers was measured at the initial temperatures from 45°C to 52°C (in 1°C steps) for 3 and 5 s each. The tests were carried out in three independent test runs on the skin of 3 different donors and averaged in the evaluation.

2.4. Data processing

The evaluator software allows the temperature levels to be read out over time for defined range of the two‐dimensional, incorrectly coded IR image (so‐called regions of interest). For this purpose, the image sections of both the IR image and the histological cryocut image for every individual skin sample were clearly assigned to each other, aligned at the lower limit of the ceramic heating plate (Figure 2). In the respective anatomical layers, thus defined, horizontal measuring lines of the same length were defined in the IR image. The course of the temperature progression in the respective layers over time was used as mean values for the comparative evaluation. The data thus determined were exported from the measurement software and processed into MS Excel for Mac (V16.34) for the graphic representation of the data. The graphs were created using DataGraph 4.5 (Visual Data Tools Inc., USA).

FIGURE 2.

Overlay of magnification‐identical image of skin sample cryocut (left) and false color‐coded IR image (right) for the identification of the anatomical skin layers in the IR image

3. RESULTS

The measurement shows a calculated and effective heat transfer from the medical device into the skin. The target temperatures (>42°C–43°C) for activating TRPV1 in the target compartment of the skin (vital epidermis) were reached. 36 With an application of the medical device for over 5 s (Figure 3), the temperature threshold was exceeded much longer compared to 3 s (Figure 4), so that an activation of TRPV1 appears more certain here.

FIGURE 3.

Mean temperature gradients based on the anatomical layers after 3 s application duration. The beginning of the temperature entry and the activation range of the TRPV1 (>42–43°C) are shown

FIGURE 4.

Mean temperature gradients based on the anatomical layers after 5 s application duration. The beginning of the temperature entry and the activation range of the TRPV1 (>42–43°C) are shown

Considering the results of the thermodiffusion into the vital epidermis as the target compartment, it becomes clear that in the given experimental set‐up the application temperature has only a small influence on the temperature curve compared to the application duration (Figures 5 and 6). As stated above, heat conductance into the skin and therefor the achievement of the activation temperature of TRPV1 of 42°C–43°C is dependent on regional as well as intra‐ and interindividual differences of skin texture, justifying a variable application temperature within defined limits. In addition, not only the duration of the necessary tempering level for activating TRPV1 does not appear to be constant, also the level of response of the TRPV1 receptors to heat stimuli varies with different temperatures.

FIGURE 5.

Mean temperature gradients in the vital epidermis (target compartment) based on the application temperature after 3 s application duration

FIGURE 6.

Mean temperature gradients in the vital epidermis (target compartment) based on the application temperature after 5 s application duration

Figures 7 and 8 show the min‐max curves for 3 s application (Figure 7) and 5 s application (Figure 8) for descending application temperature. Here too, it becomes clear that the thermal conductive properties of skin samples from different donors vary and cannot be judged by the anatomical and barrier‐related integrity. This results in a temperature difference of about 2°C for the target compartment. These observations are also due to interindividual, biologically justified variability.

FIGURE 7.

Min/max temperature gradients in the vital epidermis based on the respective application temperature after 3 s application duration

FIGURE 8.

Min/max temperature gradients in the vital epidermis based on the respective application temperature after 5 s application duration

In Figures 3 and 4 the delay of heat diffusion from the heat source to the skin tissue is shown. The constant thermal conductivity of the skin leads to a delay of the temperature maximum in the skin tissue by 5–6 s after 3 s and after 5 s heat application (Figures 3 and 4). The almost synchronous temperature maxima in different skin layers suggest a steady state, which can be justified by the achieved thermal conductivity of the skin tissue.

4. DISCUSSION

The heat output (Q) transmitted by the heat conduction is described by the Fourier law. 37 For the simplified case of a solid body (in this case = skin sample) with two parallel surfaces (top and bottom) is:

TW1 represents the warmer surface (skin surface), TW2 the colder surface (skin base = copper plate), A the surface (surface of the heat sensor), λ the thermal conductivity (temperature‐dependent characteristic of material) and d for the thickness of the body (skin thickness). 38 , 39 The heat transport is also described by the concept of heat flux density (q). 40 Since these laws apply only to media having a homogenic composition, it cannot be applied in the present case. Furthermore, lateral heat dissipation is very likely, so that the calculation of heat conduction variables did not prove successful for biological material with an inhomogeneous and variable composition. 33 , 41 Against this background, the experiments carried out on ex vivo human skin reflect the processes of thermal diffusion at and immediately after the application of the medical device far better. Nevertheless, it must be noted that the experiment does not exactly simulate the vital conditions of perfused skin. The removal of the skin from the tissue bandage also altered the lateral heat diffusion. Due to hygienic and ethical concerns, examinations on perfused, vital skin with lateral IR imaging is not appropriate. The strategy for the experiments was chosen to produce almost realistic results. A lateral heat loss is very likely when skin samples are used, and it can be assumed that the real isotherms in the anatomical layers are slightly higher.

The interpretation of the present data in the light of the intended use of the medical device under real life conditions must consider the wide range of biological variability of the skin. Especially the inter‐ and intra‐individually varying anatomical thickness of the relevant skin layers and their composition, in particular their moisture and lipid content will contribute to a different heat conductance into the skin. 42 In addition, special features arise from the pathological changes in the skin structure accompanying pruritic dermatoses as well as by the intensity of the dermatosis to be treated. Furthermore, it can be assumed that in chronic itching states, both the expression pattern and the functionality of TRPV1 can change. 43 The resulting individual conditions of heat transfer and conduction between micro compartments cause individual heat transfer when applied. 44 However, since under real life conditions the biological characteristics in terms of the thickness of the skin (application area, age, sex) and of the water content, which is particularly relevant for the thermal conductivity of the upper layers (stratum corneum), vary greatly. 45 , 46 , 47 Therefore, on the basis of the available data, it can be assumed that an application of the medical device for 3 s may not always sufficiently effective under all application conditions. Rather, an application should be preferred for 5 s to ensure sufficient heat diffusion. In addition, the data also show that the maximum tissue temperatures reached appear unsuitable for triggering direct thermal damage according to denaturation of structural proteins. Thus, a relevant security risk, even with repeated application, is theoretically very unlikely or excluded. Nevertheless, safety, especially with repeated use, has yet to be demonstrated in clinical trials. In the literature there are some clinical studies with local hyperthermia and with technically comparable parameters. These show both inhibitory effects on histaminergic induced itching and safe use of comparable Peltier devices. 35 , 48 , 49

In summary, it can be stated that the present test results demonstrate a relevant cutaneous heat input with temperature maxima of ≥43°C after application of local hyperthermia of 45°C to 52°C for 5 s with “bite away” electronic (Mibetec GmbH, Sandersdorf‐Brehna, Germany). As shown previously in in vivo experiments, the pain threshold in humans for heat application of 3 s duration is around 48°C to 50°C making it reasonable to apply an standardized temperature of ∼51°C. 50 However, the clinically relevant performance and safety of the medical device must be proven in clinical studies in populations with defined clinical indication of pruritic diseases. This includes different application temperatures, durations and regimes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Johannes Wohlrab has received fees for lecturing and/or consulting, and/or received funding for scientific projects and/or clinical studies from Abbvie, ACA, Actelion, Allergika, Almirall, Agfa, Aristo, Astellas, BayPharma, Baxalta, Beiersdorf, BMS, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bombastus, Celgene, Dermapharm, Ei, Evolva, Evonik, Galderma, Grünenthal, GSK, Hexal, Infectopharm, Janssen‐Cilag, Jenapharm, Johnson & Johnson, Klinge, Klosterfrau, Leo, Lilly, L‘Oréal, Mavena, Medac, Medice, Mibe, MSD, Mylan, Novaliq, Novartis, Pfizer, Pohl‐Boskamp, Riemser, Sanofi, Skinomics, Wolff. Tim Mentel is an employee of Mibetec GmbH. Adina Eichner declares no conflict of interest. The investigations have been fully funded by Mibetec GmbH (Sandersdorf‐Brehna, Germany).

Wohlrab J, Mentel T, Eichner A. Efficiency of cutaneous heat diffusion after local hyperthermia for the treatment of itch. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29:e13277. 10.1111/srt.13277

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yosipovitch G, Misery L, Proksch E, Metz M, Stander S, Schmelz M. Skin barrier damage and itch: review of mechanisms, topical management and future directions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(13):1201‐1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Misery L, Weisshaar E, Brenaut E, et al. Pathophysiology and management of sensitive skin: position paper from the special interest group on sensitive skin of the International Forum for the Study of Itch (IFSI). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2):222‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Najafi P, Carre JL, Ben Salem D, Brenaut E, Misery L, Dufor O. Central mechanisms of itch: a systematic literature review and meta‐analysis. J Neuroradiol. 2020;47(6):450‐457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cevikbas F, Lerner EA. Physiology and pathophysiology of itch. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(3):945‐982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co‐opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171(1):217‐228.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdo H, Calvo‐Enrique L, Lopez JM, et al. Specialized cutaneous Schwann cells initiate pain sensation. Science. 2019;365(6454):695‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmelz M. How do neurons signal itch? Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:643006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Solinski HJ, Rukwied R. Electrically evoked itch in human subjects. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:627617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Riccio D, Andersen HH, Arendt‐Nielsen L. Mild skin heating evokes warmth hyperknesis selectively for histaminergic and serotoninergic itch in humans. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dodt E. The behaviour of thermoceptors at low and high temperatures with special reference to Ebbecke's temperature phenomena. Acta Physiol Scand. 1953;27(4):295‐314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tan CL, Knight ZA. Regulation of body temperature by the nervous system. Neuron. 2018;98(1):31‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lucaciu OC, Connell GP. Itch sensation through transient receptor potential channels: a systematic review and relevance to manual therapy. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36(6):385‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487‐517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gunthorpe MJ, Chizh BA. Clinical development of TRPV1 antagonists: targeting a pivotal point in the pain pathway. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14(1‐2):56‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Winter Z, Buhala A, Otvos F, et al. Functionally important amino acid residues in the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) ion channel—an overview of the current mutational data. Mol Pain. 2013;9:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee Y, Hong S, Cui M, Sharma PK, Lee J, Choi S. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 antagonists: a patent review (2011–2014). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2015;25(3):291‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Almalty AM, Petrofsky JS, Al‐Naami B, Al‐Nabulsi J. An effective method for skin blood flow measurement using local heat combined with electrical stimulation. J Med Eng Technol. 2009;33(8):663‐669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng W, Wen H. Heat activation mechanism of TRPV1: New insights from molecular dynamics simulation. Temperature (Austin). 2019;6(2):120‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lopes C, Liu Z, Xu Y, Ma Q. Tlx3 and Runx1 act in combination to coordinate the development of a cohort of nociceptors, thermoceptors, and pruriceptors. J Neurosci. 2012;32(28):9706‐9715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choveau FS, Ben Soussia I, Bichet D, Franck CC, Feliciangeli S, Lesage F. Convergence of multiple stimuli to a single gate in TREK1 and TRAAK potassium channels. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:755826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maksaev G, Milac A, Anishkin A, Guy HR, Sukharev S. Analyses of gating thermodynamics and effects of deletions in the mechanosensitive channel TREK‐1: comparisons with structural models. Channels (Austin). 2011;5(1):34‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cevikbas F, Wang X, Akiyama T, et al. A sensory neuron‐expressed IL‐31 receptor mediates T helper cell‐dependent itch: involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):448‐460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shim WS, Tak MH, Lee MH, et al. TRPV1 mediates histamine‐induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12‐lipoxygenase. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2331‐2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geppetti P, Nassini R, Materazzi S, Benemei S. The concept of neurogenic inflammation. BJU Int. 2008;101(3):2‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kozyreva TV, Khramova GM. Effects of activation of skin ion channels TRPM8, TRPV1, and TRPA1 on the immune response. Comparison with effects of cold and heat exposure. J Therm Biol. 2020;93:102729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee YM, Kang SM, Chung JH. The role of TRPV1 channel in aged human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;65(2):81‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gao M, Wang Y, Liu L, Qiao Z, Yan L. A patent review of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 modulators (2014‐present). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2021;31(2):169‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pearson J, Lucas RA, Crandall CG. Elevated local skin temperature impairs cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses to a simulated haemorrhagic challenge while heat stressed. Exp Physiol. 2013;98(2):444‐450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henriques FC, Moritz AR. Studies of thermal injury: I. The conduction of heat to and through skin and the temperatures attained therein. A theoretical and an experimental investigation. Am J Pathol. 1947;23(4):530‐549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hagenacker T, Ledwig D, Busselberg D. Feedback mechanisms in the regulation of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) in the peripheral nociceptive system: role of TRPV‐1 and pain related receptors. Cell Calcium. 2008;43(3):215‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luo L, Wang Y, Li B, et al. Molecular basis for heat desensitization of TRPV1 ion channels. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGee MP, Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC. The local pathology of interstitial edema: surface tension increases hydration potential in heat‐damaged skin. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(3):358‐367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kashcooli M, Salimpour MR, Shirani E. Heat transfer analysis of skin during thermal therapy using thermal wave equation. J Therm Biol. 2017;64:7‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Diller KR. Heat transfer in health and healing. J Heat Transfer. 2015;137(10):1030011‐10300112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wohlrab J, Voss F, Muller C, Brenn LC. The use of local concentrated heat versus topical acyclovir for a herpes labialis outbreak: results of a pilot study under real life conditions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:263‐271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bagood MD, Isseroff RR. TRPV1: role in skin and skin diseases and potential target for improving wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11): 6135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen S, Wang J, Casati G, Benenti G. Nonintegrability and the Fourier heat conduction law. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2014;90(3):032134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moritz AR, Henriques FC. Studies of thermal injury: II. The relative importance of time and surface temperature in the causation of cutaneous burns. Am J Pathol. 1947;23(5):695‐720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goudarzi P, Azimi A. Numerical simulation of fractional non‐Fourier heat conduction in skin tissue. J Therm Biol. 2019;84:274‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khalil N, Garzo V. Heat flux of driven granular mixtures at low density: stability analysis of the homogeneous steady state. Phys Rev E. 2018;97(2‐1):022902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moritz AR. Studies of thermal injury: III. The pathology and pathogenesis of cutaneous burns. An experimental study. Am J Pathol. 1947;23(6):915‐941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barbenel JC, Makki S, Agache P. The variability of skin surface contours. Ann Biomed Eng. 1980;8(2):175‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sanchez‐Moreno A, Guevara‐Hernandez E, Contreras‐Cervera R, et al. Irreversible temperature gating in trpv1 sheds light on channel activation. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Petrofsky J, Paluso D, Anderson D, et al. The ability of different areas of the skin to absorb heat from a locally applied heat source: the impact of diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(3):365‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Robertson K, Rees JL. Variation in epidermal morphology in human skin at different body sites as measured by reflectance confocal microscopy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(4):368‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Greene RS, Downing DT, Pochi PE, Strauss JS. Anatomical variation in the amount and composition of human skin surface lipid. J Invest Dermatol. 1970;54(3):240‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kakasheva‐Mazhenkovska L, Milenkova L, Gjokik G, Janevska V. Variations of the histomorphological characteristics of human skin of different body regions in subjects of different age. Prilozi. 2011;32(2):119‐128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yosipovitch G, Duque MI, Fast K, Dawn AG, Coghill RC. Scratching and noxious heat stimuli inhibit itch in humans: a psychophysical study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:629‐634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muller C, Grossjohann B, Fischer L. The use of concentrated heat after insect bites/stings as an alternative to reduce swelling, pain, and pruritus: an open cohort‐study at German beaches and bathing‐lakes. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:191‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dewhirst MW, Viglianti BL, Lora‐Michiels M et al. Basic principles of thermal dosimetry and thermal thresholds for tissue damage from hyperthermia. Int J Hyperth. 2003;19(3):267‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.