Abstract

The profession of pharmacy has come to encompass myriad identities, including apothecary, dispenser, merchandiser, expert advisor, and health care provider. While these identities have changed over time, the responsibilities and scope of practice have not evolved to keep up with the goals of the profession and the level of education of practicing pharmacists in the United States. By assuming that the roles of the aforementioned identities involve both product-centric and patient-centric responsibilities, our true professional identity is unclear, which can be linked to the prevalence of the impostor phenomenon within the profession. For pharmacy to truly move forward, a unified definition for the profession is needed by either letting go of past identities or separating these identities from each other by altering standards within professional degree programs and practice models. Without substantial changes to the way we approach this challenge as a profession, the problems described will only persist and deepen.

Keywords: student pharmacists, pharmacists, impostor phenomenon, professional identity

INTRODUCTION

What do you see when you look in the mirror? The question is rather simple, but for pharmacists, the answer is likely complicated and inconsistent across individuals and practice settings. Elaborate metaphors aside, the issue of how we respond to this simple inquiry related to our professional “reflections” is one of the core existential crises facing the pharmacy profession and, by extension, pharmacy education.

Many in the profession who look in the proverbial mirror may see themselves reflected back wearing their white coats, proud of the service to others and commitment to excellence that the white coat represents. This identity development may begin with the symbolic white coat ceremony, as students are prompted to consider their evolution toward identifying as a student pharmacist. As novice student pharmacists insert each arm into their new white coat and straighten the lapels to embrace the responsibilities of becoming a pharmacist for the first time, they may actually find themselves asking, what does it really mean to be a pharmacist? And yet, others who wear the white coat (or perhaps even those most proud of wearing it) may discover they now struggle with how others view them in their white coats.

The concept of impostor phenomenon may begin the moment a student becomes a student pharmacist by donning their white coat. Imposter phenomenon is defined as the internal experience of intellectual “phoniness” that is often experienced by high-achieving individuals who, by definition, are “focused on attaining success but never being satisfied irrespective of how much is achieved.” 1 These individuals, including pharmacists, may have fraudulent feelings when evaluating their current or future roles and responsibilities while simultaneously never feeling satisfied. Literature has pointed to student pharmacists, pharmacy residents, and pharmacists experiencing feelings of imposter phenomenon at various stages of their careers. 2-4 Although considerable focus is being placed on understanding and overcoming the imposter phenomenon, it must first be acknowledged that the emergence and presence of the phenomenon as a challenge in the profession cannot be extricated from the existential identity crisis facing pharmacy as a whole. Simply put, imposter phenomenon itself could be viewed as a symptom of the larger challenge encompassing all of pharmacy: Who are we, and what is our role on the team and in the health care system? This identity crisis may be due, in part, to rapid advancements in science and technology, increased workforce pressures, and inherent public expectations that make defining the pharmacist’s contribution to health care somewhat complicated. 5

One way the pharmacy education system has tried to alleviate this professional identity crisis is by requiring interprofessional education activities within pharmacy curricula. Interprofessional education activities are intended to help health care professions students understand the different roles, values, and perspectives they each bring to the table and to combine those assets into an effective, collaborative team. 6 Unfortunately, despite these efforts, not only do pharmacy students still often fail to understand their role within the health care team, 7, 8 but they are also not viewed as favorably as other professions. 9 Initial feelings of inadequacy give way to professional identity formation over many years, as competence and confidence develop. The lack of clear roles and responsibilities for our profession has large impacts for trainees, practitioners, and the future of pharmacy. 10, 11 This ambiguity intensifies the imposter phenomenon that trainees and even practicing pharmacists may experience because they are unable to clearly articulate their role in the health care team. 8 Though a sizable focus is placed on recognizing certain aspects of individual imposter phenomenon and how to overcome it, this projects onto the identity crisis the profession is experiencing as a whole. If current pharmacists and the Academy are unable to articulate the roles and responsibilities of a pharmacist under a unified definition, how can student pharmacists be expected to answer that call?

DISCUSSION

The image of pharmacy, as reflected by an individual pharmacist, is also complicated by the history and evolution of the profession over time. As pharmacy education has evolved from primarily product-centric responsibilities (BSPharm) to patient-centric responsibilities (PharmD), 12 pharmacists should be prepared to assume new and emerging roles that may place them in uncharted waters. This initial move from the BSPharm to the PharmD in 2000 could have initiated the feelings of imposter phenomenon for the profession, as preceptors and educators with BSPharm degrees were forced to educate and train student pharmacists on a new identity that they themselves had yet to form. Or, worse, and perhaps more likely in some cases, changes in the profession may have been unwelcome to some already in practice, particularly when those changes did not match up with corresponding changes to payment models. Regardless of the internal effect that the transition to the PharmD has had on the profession, the impact that pharmacists have on direct patient care outcomes is clear and convincing. Outcomes of pharmacist-led medication management continue to demonstrate positive impacts for patients and the health care system; however, we have yet to truly define our role in the new value-based health care model. This and many other issues bring about the purpose of this article: to call to light the imposter phenomenon that the profession experiences, undoubtedly because the role of a pharmacist in the 21st century is unclear, as is the way in which we need to move past traditional perceptions to truly advance our profession.

Kellar and colleagues frame the five prominent pharmacist identity discourses over the past 100 years as apothecary, dispenser, merchandiser, expert advisor, and health care provider. 10 But, the traditional and most widely recognized role of a pharmacist has been related to dispensing medications. 12 Considering the highly regulated nature of the profession of pharmacy, these traditional responsibilities have included following rules and statutes, complying with controlled substance and other medication-related laws, and conducting transactional activities. Instead of focusing on outcomes, traditional responsibilities often force pharmacists into a passive and compliant mindset. In 1985, the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists proclaimed that the profession would now be a clinical profession. 13 While the American College of Clinical Pharmacy answered that call with their definition of “the area of pharmacy concerned with the science and practice of rational medication use,” 14 other pharmacy organizations did not publicly endorse this definition, leading us to still ask, what does it mean to be a clinical pharmacist?

In some respects, pharmacy programs are teaching all five roles, in addition to new opportunities that require enhanced skills and expertise, thus retaining the product-centric focus of more traditional pharmacist roles as well as expanding to the patient-centric pharmacist roles seen today. 15 Clinical pharmacists are supposed to be responsible and accountable for the safe and effective use of medications and optimizing clinical outcomes. However, this responsibility is not just relegated to pharmacists, as interprofessional teams may blur the lines of responsibilities to truly care for a patient. 11 Despite the blurred reflection we may see, our profession should still be able to define our unique role in optimizing patient care.

This baseline summary of a pharmacist’s role does not account for the modernization, changes, and evolution of professional training and the pharmacy job market in the past several decades that have led to the amalgamation of present-day pharmacy practice. It is imperative to acknowledge these significant developments in education, training, and responsibilities and their combined impact on pharmacists’ identity within health care and as health care providers, or student pharmacists may graduate without an appreciation for or understanding of their role. 11

Many institutions have realized the need for postgraduate training by providing a facilitated learning environment to train future clinical pharmacists. There has since been significant growth in pharmacy services in various specialties, and several studies have illustrated the increasing responsibilities that pharmacists undertake in different patient care settings and their value as part of the interprofessional team. 16, 17 With the increase in postgraduate training opportunities, increased certification offerings, and job descriptions that require or prefer postgraduate education, pharmacists who lack this experience may have amplified impostor feelings when considering career changes. Further, fraudulent feelings may emerge when failing to secure postgraduate training or pursuing job opportunities when one may not fulfill all the stated job experience requirements.

Furthermore, with the sustained expansion of clinical activities across practice settings, pharmacists have continued to add more responsibilities without adjusting the language and definition of the profession to account for these modifications. For example, when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Partnership for Patients program started to decrease readmission rates, pharmacy departments around the country expanded to assist in transitions of care programs. 18 However, a lack of staffing and financial resources to support these expanded services proved to be the most significant barriers in this effort. To account for the demand in additional staffing without added resources, pharmacy departments increased the scope of their responsibilities, and the profession exemplified its “diversification by edict” mentality, further impairing the lack of a unified identity for all pharmacists. For example, pharmacists have expanded into decentralized roles to support patient care by performing clinical tasks such as antimicrobial stewardship, medication reconciliation, and therapeutic drug monitoring. However, the profession’s major source of funding/revenue is generated from dispensing medications. These pharmacists have now been tasked with taking on more clinical work while still being expected to perform their core role of dispensing medications at the same level they always have.

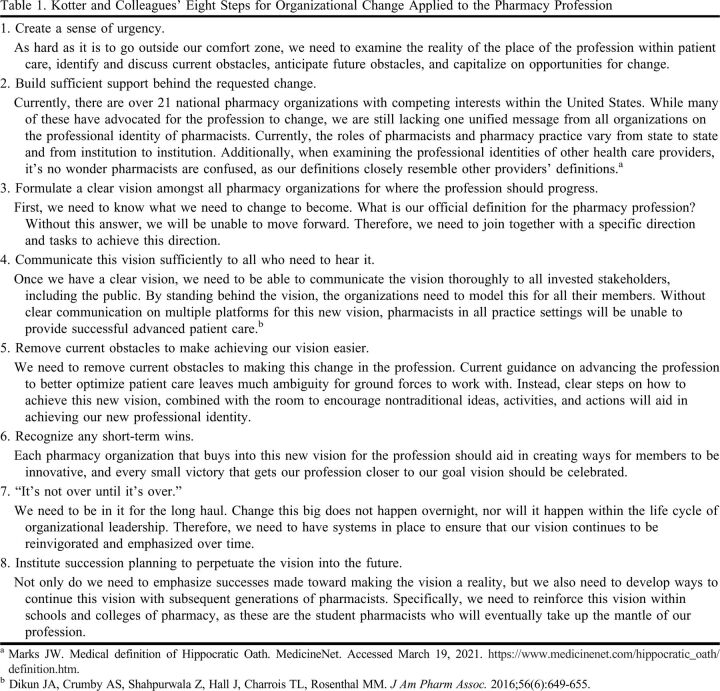

To push the profession forward, the Academy needs to be mindful of several critical mistakes to avoid, as doing so could force the profession backward. Kotter and colleagues developed an eight-step model useful for implementing organizational change; however, these steps can also be applied to the pharmacy profession (Table 1). 19 The type of change suggested in this model will take time, though change pursued and implemented at too rapid a pace can have its own consequences. Both the academic and practice settings leave little room for error or failure, leaving many pursuing perfection despite its impossibility. Pharmacists may also feel the need to consistently validate their competence and justify their value. This maladaptive perfectionism leaves pharmacists being driven by fear of failure and an overwhelming need to hide their lack of perfectionism. 20 We need to examine this mindset closely and offer proactive methods for student pharmacists to prepare not only for the feelings of imposter phenomenon but also for coping with mistakes, insecurities, and self-doubt. 21 Furthermore, this desire for perfectionism can also be driven by the need to meet expectations of the public and other professionals; however, do we even know what these expectations are?

Table 1.

Kotter and Colleagues’ Eight Steps for Organizational Change Applied to the Pharmacy Profession

CONCLUSION

We, as pharmacists, have struggled to recognize our proverbial reflections clearly in the mirror because we have no clear definition of what it truly means to be a pharmacist. In the absence of a unified definition, 12 many pharmacists may attempt to live up to all the names and roles by trying to be all things to all people. This creates both an unreasonable and unsustainable expectation on the individual to live up to the unmet (and possibly unknown) expectations of the various constituencies in our lives and practice settings, thereby exacerbating the feelings of imposter phenomenon and overachievement. It is time to accelerate our practice transformation. 22 Our profession needs to take the following steps:

Define and clearly articulate our role as the “medication expert” to other health care providers, the public, and ourselves.

Push forward with achievable standards for the entire pharmacy profession in a way that demonstrates our effort and engagement to optimizing patient care. 23

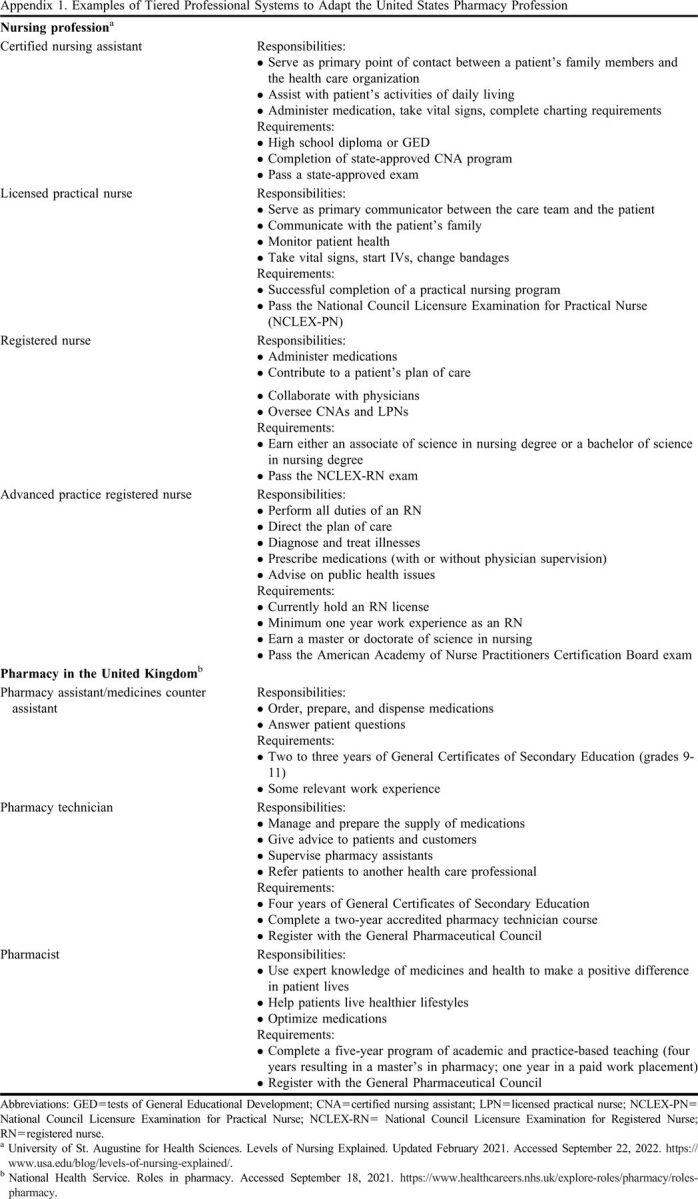

Consider a tiered system within pharmacy education, as demonstrated within nursing education or pharmacy practice in the United Kingdom, thereby giving students the flexibility to determine which identity suits them best based on established definitions for the profession (Appendix 1).

Perhaps it is time that we look in the mirror and truly ask ourselves, who do we see? Who do we truly want to be?

Appendix 1.

Examples of Tiered Professional Systems to Adapt the United States Pharmacy Profession

REFERENCES

- 1.Clance PR, Imes SA. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 1978;15(3):241‐247. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan JB, Ryba NL. Prevalence of impostor phenomenon and assessment of well-being in pharmacy residents. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(9):690-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle J, Malcom DR, Barker A, Gill R, Lloyd M, Bonenfant S. Assessment of impostor phenomenon in student pharmacists and faculty at two doctor of pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2021;85(5):Article 8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the impostor phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Ed. 1998;32:456-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John C. “The changing role of the pharmacist in the 21st century.” The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018;300(7909). https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/opinion/the-changing-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-the-21st-century [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung H, Park KH, Min YH, Ji E. The effectiveness of interprofessional education programs for medical, nursing, and pharmacy students. Korean J Med Educ. 2020;32(2):131-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curley LE, Jensen M, McNabb C, et al. . Pharmacy students’ perspectives on interprofessional learning in a simulated patient care ward environment. Am J Pharm Ed. 2019;83(6):6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble C, O’Brien M, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: students’ perceptions of their curricular experience and professional identity formation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6(3):327-339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurston MM, Chesson MM, Harris EC, Ryan GJ. Professional stereotypes of interprofessional education naïve pharmacy and nursing students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(5):Article 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellar J, Paradis E, van der Vleuten CPM, oude Egbrink MGA, Austin Z. A historical discourse analysis of pharmacist identity in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(9):Article 7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore GD, Bradley-Baker LR, Gandhi N, et al. . Pharmacists are not mid-level providers. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(3):8566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter B. Evolution of clinical pharmacy in the US and future directions for patient care. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(3):167-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Directions for clinical practice in pharmacy: proceedings of an invitational conference conducted by the ASHP Research and Education Foundation and the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1985;42(6):1287-1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):816-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle CJ. We are educating pharmacists, not “PharmDs”. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(9):Article 7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas MC, Acquisto NM, Shirk MB, Patanwala AE. A national survey of emergency pharmacy practice in the United States. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2016;73(6):386-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacci JL, Bigham KA, Dillon‐Sumner L, et al. . Community pharmacist patient care services: a systematic review of approaches used for implementation and evaluation. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2:423-432. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, American Pharmacists Association. ASHP-APhA medication management in care transitions best practices. https://www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Practice/Resource-Centers/Transitions-of-Care?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly. Accessed March 19, 2021.

- 19.Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Rev. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2. Accessed March 19, 2021.

- 20.Thomas M, Bigatti S. Perfectionism, imposter phenomenon, and mental health in medicine: a literature review. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:201-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaDonna KA, Ginsburg S, Watling C. “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: what physicians’ self-assessment of their performance reveals about imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):763-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chase PA, Allen DD, Boyle CJ, DiPiro JT Scott SA, Maine LL. Advancing Our Pharmacy Reformation- Accelerating Education and Practice Transformation: Report of the 2019-2020 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):ajpe8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ocampo ACG, Wang L, Kiazad K, Restubog SLD, Ashkanasy NM. The relentless pursuit of perfectionism: a review of perfectionism in the workplace and an agenda for future research. J Organ Behav. 2020;41:144-168. [Google Scholar]