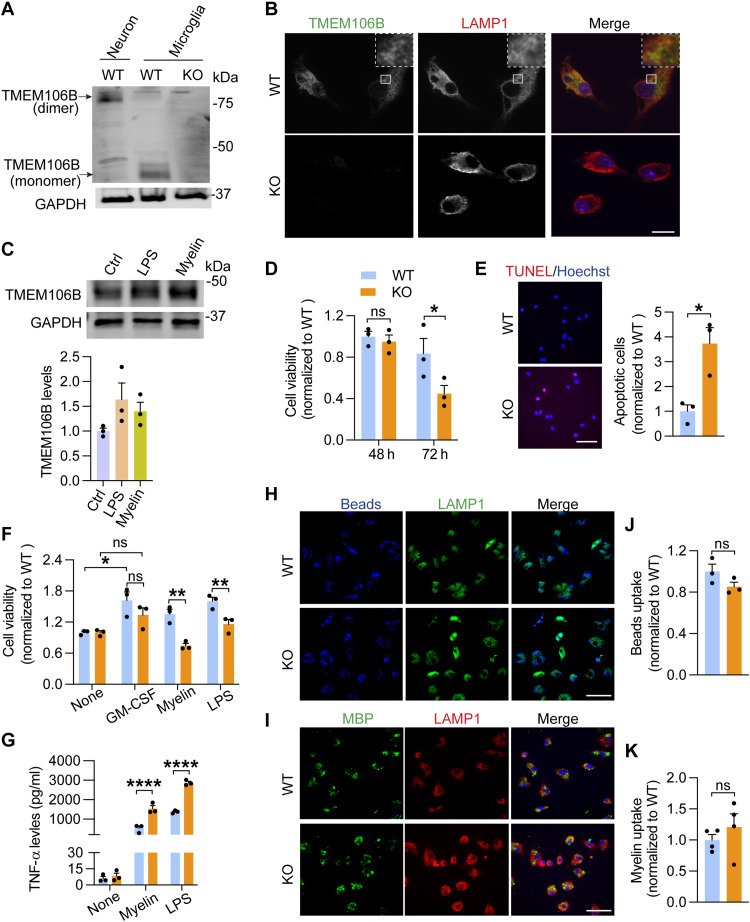

Fig. 8. TMEM106B deficiency in microglia leads to decreased cell viability and enhanced inflammation.

(A) Western blot analysis of primary cortical neuron and microglia lysates as indicated. Lysates were kept cold to allow the detection of TMEM106B dimers. (B) WT and KO microglia were stained with TMEM106B and LAMP1 antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) WT primary microglia were untreated or treated with myelin or LPS treatment for 24 hours. TMEM106B levels relative to GAPDH were quantified from three independent samples. (D) WT and KO primary microglia were grown in cell culture for the indicated times, and the number of microglia was quantified. Data represent the means ± SEM; two-way ANOVA (n = 3). (E) WT and KO primary microglia 72 hours after plating were analyzed for apoptosis using TUNEL staining. Scale bar, 50 μm. The percentage of apoptotic cells was quantified. Data represent the means ± SEM; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (n = 3). (F) WT and KO primary microglia were treated with GM-CSF, myelin, or LPS for 24 hours. The number of microglia was quantified. Data represent the means ± SEM; two-way ANOVA (n = 4). (G) WT and KO primary microglia were either untreated or treated with myelin and LPS for 24 hours and TNF-α levels in the medium were quantified. Data represent the means ± SEM; two-way ANOVA (n = 3). (H to K) WT and KO primary microglia were fed with fluorescence-labeled Latex beads (H) or myelin (I). Cells were stained with LAMP1 and MBP antibodies as indicated. Scale bar, 50 μm. The fluorescence intensities from beads (H) or MBP (I) per cell were quantified. Data represent the means ± SEM; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (n = 3 to 4 independent experiments). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.