Abstract

Background/Aim: Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) develop in a subset of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) treated with immune-checkpoint-inhibitors (ICIs). Evidence regarding the prognostic impact of irAEs remains limited in these patients.

Patients and Methods: Ninety-one consecutive patients with mRCC treated with ICIs were retrospectively analyzed. Overall survival (OS) rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. In multivariate analysis, predictors of OS were analyzed using the Cox-proportional-hazards-model.

Results: Twenty-nine patients were treated with the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab. According to International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium risk classification, 27/47/17 patients were classified into favorable/intermediate/poor risk categories. The 1, 3, and 5-year OS-rates were 89, 70, and 57%, respectively. A total of 67 irAEs occurred in 44 patients (48%), including 15 patients with grade 3-4. OS was significantly longer in patients with irAEs (p=0.01). In multivariate analysis, Karnofsky performance status, prior nephrectomy, and irAEs were independent significant predictors of OS.

Conclusion: In our study, irAEs were significantly associated with OS in mRCC patients treated with ICIs.

Keywords: Immune-related adverse event, metastatic renal cell carcinoma, immune checkpoint inhibitor

The treatment scenario for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has undergone a complete change over the last few years. The current strategy of systemic therapy for mRCC is rapidly changing due to the increased usage of novel immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (1,2). Nivolumab is a novel targeted agent that has been available in clinical practice for the treatment of mRCC (3). The CheckMate 025 study has demonstrated its promising anti-tumor efficacy and safety profile (3). We have previously reported on the characteristics, efficacies, and safety profile of nivolumab in Japanese patients with mRCC (4-7). Combination therapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab has become the standard first-line treatment for intermediate or poor risk patients with previously untreated mRCC (8,9).

Despite their clinical efficacy, ICIs can cause a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), limiting their use in some patients. The exact pathophysiology of irAE is still unknown, but various hypotheses have been formulated. Potential mechanisms include increased T-cell activity against antigens present in both the tumor and healthy tissue and increased levels of preexisting autoantibodies (10). In recent years, there has been increasing evidence that intestinal bacteria are involved in the function of intestinal CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with anti-tumor immune activity, which may affect the efficacy of ICI (11). Most irAEs tend to be self-limiting; however, in some severe cases (grade ≥3) potentially life-threating events occur (12).

Although the relationship between irAEs and clinical benefit has not yet been clarified, we and others reported a potential association between irAEs and clinical benefit in some cancer types (13-16). In addition, previous retrospective studies have demonstrated a relationship between irAEs and response rates and survival in patients with mRCC (17-19). Hence, there is a need to identify predictive biomarkers of both efficacy and toxicity associated with the use of ICIs to guide treatment decisions.

The present study investigated the prognostic impact of irAEs in patients with mRCC treated with ICIs, including nivolumab monotherapy and the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab. The incidence, grade, and patterns during ICI treatments in mRCC patients in real-world clinical practice in Japan were also assessed.

Patients and Methods

Patient selection. We retrospectively evaluated 91 consecutive patients with mRCC who received ICIs between 2013 and 2022 at our institution. The internal ethics review board of the Cancer Institute Hospital (ID:2012-1008) approved this retrospective study.

Protocol for nivolumab monotherapy and combinations of nivolumab plus ipilimumab. In nivolumab monotherapy, nivolumab (240 mg/body) was intravenously administered every 2 weeks. All patients receiving nivolumab monotherapy had previously had one or more tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies that failed. In combination therapy, nivolumab and ipilimumab were administered intravenously on the same day during the induction phase and were given four times. In the subsequent maintenance phase, nivolumab alone was administered every 2 weeks. In both treatments, the schedule modification of nivolumab from 240 mg/body/2 weeks to 480 mg/body/4 weeks was allowed and postponement of dosing was also allowed depending on the patient conditions or irAEs.

Disease was assessed using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were regularly caried out at 4- to 12-week intervals depending on the patient condition.

Outcome assessment. For the assessment of oncological outcomes during ICI treatments, overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rates (ORRs), and disease control rates (DCRs) were evaluated. OS was calculated from the initiation of ICI treatments to death from any cause. PFS was calculated from the initiation of ICI treatments until disease progression or death from any cause. Patients lost to follow-up were censored at the time of last contact. The treatment efficacy was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 (20). ORR was defined as the sum of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) rates, and DCR was defined as the sum of CR, PR, and stable disease (SD) rates.

Prognostic variables. The prognostic variables were age, sex, prior nephrectomy, histology, method of ICI administration, time of diagnosis to systemic therapy, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), hemoglobin, corrected calcium, neutrophils, platelets, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, neutrophil lymphocyte rate (NLR), and irAEs. Corrected calcium was considered normal up to 10 mg/dl using the following formula: corrected calcium = total calcium + (4 - albumin). The cut-off points of time of diagnosis to systemic therapy, KPS, hemoglobin, corrected calcium, neutrophils, and platelets were determined in accordance with the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) risk classification (3), and those of age and NLR were set with the highest value of ‘sensitivity - (1-specificity)’ in the receiver operating characteristics analysis using overall death as the endpoint.

irAEs of ICI treatments. The irAEs evaluated in this study included cutaneous, gastrointestinal, endocrine, pulmonary, hepatobiliary, and others. The grades were determined according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (21).

Statistics. Continuous variables are expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and were compared using Wilcoxon tests depending on the number of groups in comparison and data distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to assess OS and PFS with comparisons made by the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify risk factors for OS. The risk was expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP-version 13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

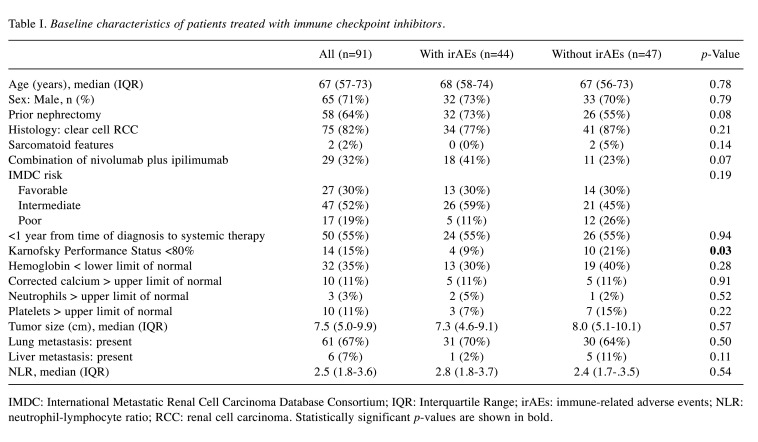

Patient characteristics. During ICI treatments, 44 patients (48%) experienced irAEs of any grade (Table I). Sixty-two and 29 patients were treated with nivolumab monotherapy and the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab, respectively. The median age was 67 years. Fifty-eight patients (64%) had prior nephrectomies. The dominant histotype was clear cell RCC in 75 patients (82%) with 2 sarcomatoid features.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

IMDC: International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium; IQR: Interquartile Range; irAEs: immune-related adverse events; NLR: neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; RCC: renal cell carcinoma. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

The development of irAEs was significantly associated with KPS (p=0.03). Other baseline characteristics did not significantly affect irAE emergences, although patients treated with the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab tended to have more irAEs (p=0.07).

According to the IMDC risk classification, 27, 47, and 17 patients were classified into favorable, intermediate, and poor risk categories, respectively. The 29 patients with combinations of nivolumab plus ipilimumab received first-line treatment, whereas among 62 patients with nivolumab monotherapy, 45, 14, and 3 patients received second-, third-, and fourth-line treatments, respectively, after tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies had failed.

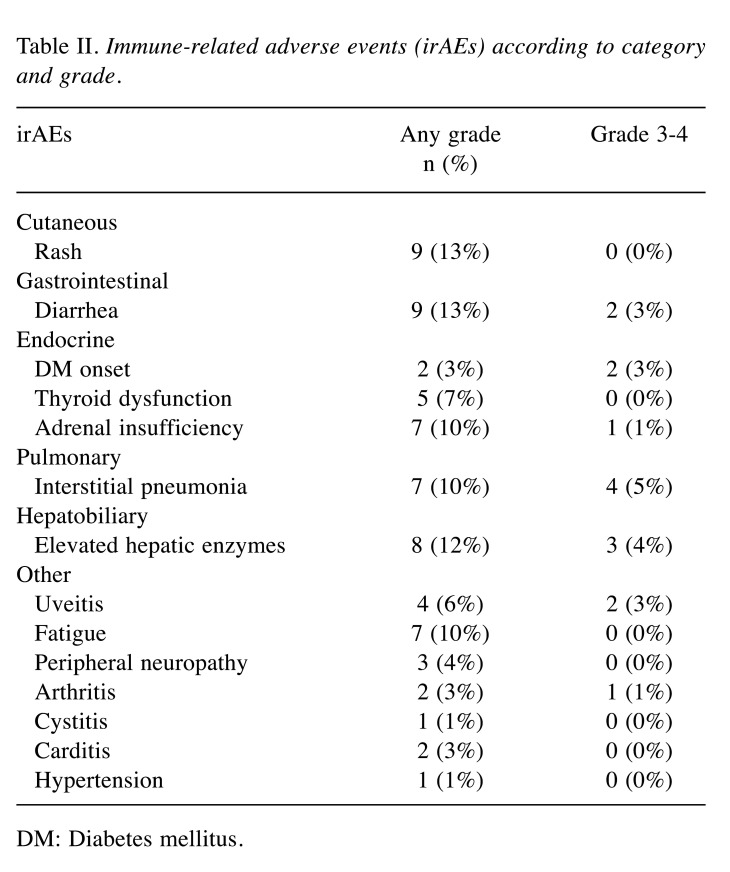

irAE profiles. Overall, 44/91 patients (48%) experienced 67 irAEs of any grade (Table II). The median time from ICI treatments to irAE onset was 3 months (IQR=2-5 months), which was significantly shorter in patients with the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab than in patients with nivolumab monotherapy (2 vs. 4 months; p=0.02). Steroid administrations were used in 19/44 patients (43%) for irAEs. Among the 67 irAEs, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, endocrine, pulmonary, hepatobiliary, and others were 9, 9, 14, 7, 8, and 20, respectively.

Table II. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) according to category and grade.

DM: Diabetes mellitus.

A total of 15 grade 3 or higher irAEs occurred in 15 patients (16%), including 12 patients with grade 3 irAEs and 3 patients with grade 4 irAEs. No patients with grade 5 irAEs were identified. Pulmonary manifestations were most frequently observed (4/15, 27%). Among these 15 patients, 14 patients (93%) received steroid treatments. In addition, one of the patients was using immunosuppressive drugs. Patients receiving the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab had significantly more grade ≥3 irAEs than patients receiving nivolumab monotherapy (38% vs. 7%, respectively, p<0.01).

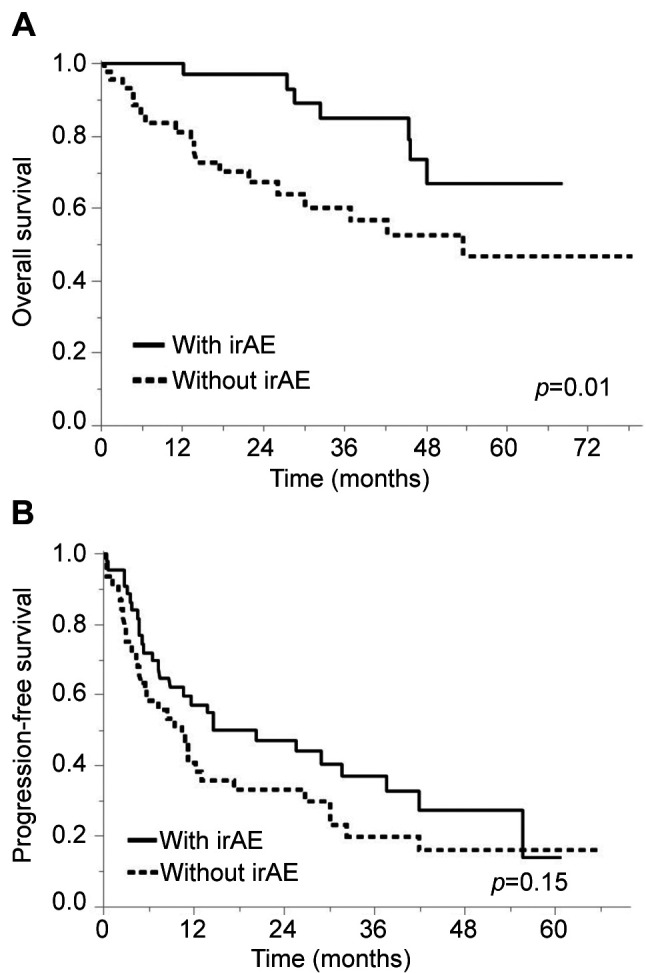

Survival according to irAEs. During a median follow-up of 27 months (IQR=11-49 months), 61 patients (67%) experienced disease progression and 25 patients (27%) died. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 89, 70, and 57%, respectively, and median OS was not reached (Figure 1A). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year PFS rates were 48, 28, and 17%, respectively, and median PFS was 11 months (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B) curves according to immune-related adverse events.

After the initiation of ICI treatments, OS was significantly longer in patients with irAEs than in patients without irAEs (1/3/5-year OS rates: 97/85/67% vs. 81/57/47%, respectively, p=0.01). The irAE group had a better prognosis for OS in both nivolumab monotherapy (p=0.04) and the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab (p=0.01). However, PFS was not different between patients with and without irAEs (1/3/5-year PFS rates: 55/33/14% vs. 38/20/17%, respectively, p=0.15).

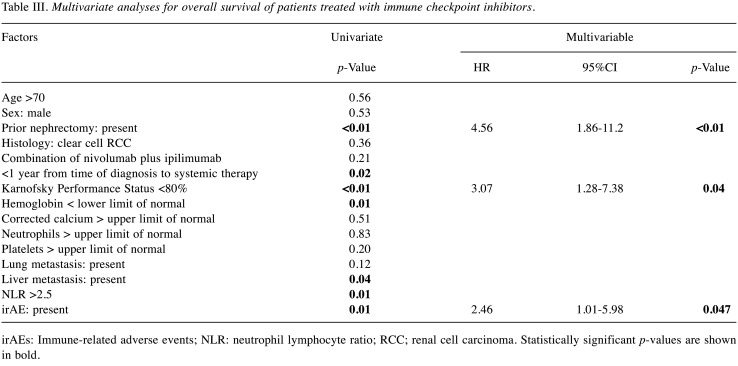

Risk factors for OS. The univariate analysis showed that prior nephrectomy, time of diagnosis to systemic therapy, KPS, hemoglobin, liver metastasis, NLR, and irAE were significant factors affecting OS (Table III). The multivariate analysis showed that the presence of irAE was an independent factor (HR=2.46, 95%CI=1.01-5.98, p=0.047), along with prior nephrectomy (HR=4.56, 95%CI=1.86-11.2, p<0.01) and KPS (HR=3.07, 95%CI=1.27-7.38, p=0.04).

Table III. Multivariate analyses for overall survival of patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

irAEs: Immune-related adverse events; NLR: neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; RCC; renal cell carcinoma. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

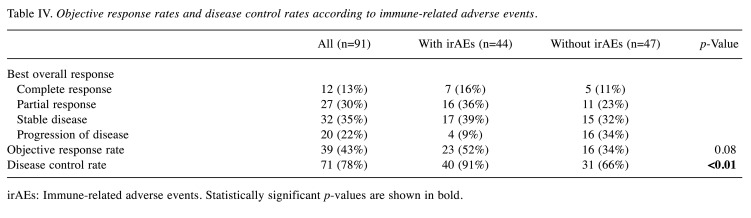

Tumor responses according to irAEs. The magnitudes of tumor responses were compared based on the development of irAEs. The DCRs in patients with irAEs were significantly higher than those in patients without irAEs (91% vs. 66%, respectively, p<0.01), although there were no significant differences in ORRs (52% vs. 34%, p=0.08) (Table IV).

Table IV. Objective response rates and disease control rates according to immune-related adverse events.

irAEs: Immune-related adverse events. Statistically significant p-values are shown in bold.

Discussion

This retrospective study showed that OS was significantly longer in patients with irAEs than in those without irAEs. Multivariate analysis indicated that the presence of irAEs was an independent factor of longer OS. Furthermore, higher DCRs were observed in patients with irAEs. These results indicated that patients who presented with irAEs were not only able to overcome irAEs by proper management but were also able to achieve long-term survival.

The therapeutic strategy depends on the severity grade of irAEs. Usually, grade 1-2 events only need symptomatic treatments and do not require specific therapies (22,23). However, the management of grade 3 or higher irAEs requires steroid treatment (23,24). Our current analysis showed that 44 patients (48%) experienced irAEs, including 15 patients (16%) with grade 3 or higher. Among these 15 patients, 14 patients received steroid treatment, and none were fatal due to irAEs. Steroid therapy is a basic treatment for irAE, but it has been noted that it may impair ICI treatment due to its recognized immunosuppressive activity (22), which is currently controversial.

IrAEs most frequently affect cutaneous, gastrointestinal, endocrine, pulmonary, and hepatobiliary systems. They rarely affect the nervous system, muscles, joints, heart, or eyes (24,25). Our results are similar to these reports. Although a previous report showed that the location of manifested irAEs had prognostic significance for OS and PFS (17), our current analysis was unable to confirm these results. Further analysis in a larger cohort is needed in this area.

Several studies showed the association between prognosis or tumor response and irAEs to ICI treatments in a variety of cancers (13,14,17,19). These associations are interesting dilemmas that oncologists face. Tolerability of ICI without adverse events may indicate a lack of efficacy. However, expression of irAEs can serve as a surrogate marker of response to ICI. Because of this association, it is important to monitor these side effects, which can be effectively treated with the appropriate use of steroids. Close follow-up is essential to ensure that patients who develop irAEs receive treatment promptly and are able to resume treatment in a timely manner after discontinuation. Patient education about symptoms that should be monitored and reported is also important. Further research is needed to identify patients who may develop adverse events and to discover predictive biomarkers that may provide greater benefit from ICI.

In the TKI era, IMDC risk classification is a useful prognostic classification in the treatment of mRCC, and treatment strategies are constructed based on this risk classification (3). KPS is one of the factors in this IMDC risk classification and was also a significant prognostic factor for OS in our multivariate analysis. However, the other five factors in the IMDC risk classification were not significant prognostic factors in our current analysis, and further validation is needed to determine whether the IMDC risk classification is a useful risk classification for mRCC patients treated with ICIs. The other significant prognostic factor for OS in our analysis was prior nephrectomy. Radical or partial nephrectomy, including cytoreductive nephrectomy (CN) for selected mRCC, is considered the backbone of managing kidney cancer patients (26). While the CARMENA trial provided practice-changing evidence that patients with intermediate or poor risk disease should not undergo CN before starting systemic treatment in the TKI era (27), the significance of performing CN in the era of ICI treatment is not clear. Further evidence needs to be gathered regarding the significance of CN in the era of ICI treatment.

This study has several limitations. First, this study was retrospective in nature and had a small sample size that may have introduced potential biases and confounding factors. Second, the combined analysis of nivolumab monotherapy and the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab resulted in cohorts with different patient backgrounds. However, the irAE group had a better prognosis for OS in each treatment group, and the combined analysis of these treatment groups makes it one of the largest cohorts of real-world analysis in Japan. Third, due to its retrospective nature and the system of irAE identification, not all irAEs might have been recognized, and any unrecorded irAEs could have affected our analyses. Fourth, the result of a better OS in the group of patients with irAEs is a possible bias that may have resulted in the occurrence of irAEs in the group of patients who survived longer. However, the significantly higher DCR in patients with irAEs suggests that a larger cohort may result in significant differences in ORR and PFS. We believe that the present results enhance the current understanding of this field and warrant further confirmation in future prospective studies with larger cohorts.

In conclusion, we showed that irAE development was positively associated with oncological outcomes of patients with mRCC treated with ICIs. Although irAEs caused by ICI treatment are a potentially fatal complications, they can lead to a good long-term outcome if properly managed. A multidisciplinary approach with a strategy that is carefully formulated not only by urologists but also by medical oncologists and pulmonologists should be recommended. Further prospective investigations with a larger sample size should be conducted to confirm these findings.

Conflicts of Interest

T. Yuasa received remuneration for a lecture from Ono Pharma (Osaka, Japan), Bristol-Myers Squibb Japan (Tokyo, Japan), and MSD Japan (Tokyo, Japan). S. Takahashi received remuneration for a lecture from MSD and Eisai, and grants from Eisai, Novartis, Taiho, MSD, Chugai, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squib, and Ono Pharmaceutical. The other Authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Y. Yasuda and T. Yuasa conceived the idea of the study. Y. Yasuda developed the statistical analysis plan and conducted statistical analyses and contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y. Yasuda, S. Takahashi, and T. Yuasa drafted the original manuscript. T. Yuasa supervised the conduct of this study. All Authors reviewed the manuscript draft and revised it critically on intellectual content. All Authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

References

- 1.Fujiwara R, Kageyama S, Yuasa T. Developments in personalized therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2022;22(6):647–655. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2022.2075347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuasa T, Urasaki T, Oki R. Recent advances in medical therapy for urological cancers. Front Oncol. 2022;12:746922. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.746922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, Eigl BJ, Ruether JD, Cheng T, North S, Venner P, Knox JJ, Chi KN, Kollmannsberger C, McDermott DF, Oh WK, Atkins MB, Bukowski RM, Rini BI, Choueiri TK. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(34):5794–5799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujiwara R, Inamura K, Yuasa T, Numao N, Yamamoto S, Masuda H, Kawauchi A, Takeuchi K, Yonese J. Efficacy and safety profile of nivolumab for Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25(1):151–157. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujiwara R, Takemura K, Fujiwara M, Yuasa T, Yasuoka S, Komai Y, Numao N, Yamamoto S, Yonese J. Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score as a predictor of prognosis in metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2021;19(2):e78–e83. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiwara R, Komai Y, Oguchi T, Numao N, Yamamoto S, Yonese J, Yuasa T. Improvement of medical treatment in japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2022;2(1):25–30. doi: 10.21873/cdp.10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamada K, Fujiwara R, Takemura K, Komai Y, Oguchi T, Numao N, Yamamoto S, Yonese J, Yuasa T. Tumor shrinkage patterns of nivolumab monotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2022;29(10):1181–1187. doi: 10.1111/iju.14964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, Arén Frontera O, Melichar B, Choueiri TK, Plimack ER, Barthélémy P, Porta C, George S, Powles T, Donskov F, Neiman V, Kollmannsberger CK, Salman P, Gurney H, Hawkins R, Ravaud A, Grimm MO, Bracarda S, Barrios CH, Tomita Y, Castellano D, Rini BI, Chen AC, Mekan S, McHenry MB, Wind-Rotolo M, Doan J, Sharma P, Hammers HJ, Escudier B, CheckMate 214 Investigators. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1277–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato R, Kojima T, Sazuka T, Yamamoto H, Fukuda S, Yamana K, Sugino Y, Hamamoto S, Nakaigawa N, Kabu K, Murakami H, Obara W. A multicentre retrospective study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab for untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2021;41(12):6199–6209. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkrief A, Derosa L, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Routy B. The intimate relationship between gut microbiota and cancer immunotherapy. Gut Microbes. 2019;10(3):424–428. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1527167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, Barlesi F, Kohlhäufl M, Arrieta O, Burgio MA, Fayette J, Lena H, Poddubskaya E, Gerber DE, Gettinger SN, Rudin CM, Rizvi N, Crinò L, Blumenschein GR Jr, Antonia SJ, Dorange C, Harbison CT, Graf Finckenstein F, Brahmer JR. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujii T, Naing A, Rolfo C, Hajjar J. Biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade in cancer treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;130:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussaini S, Chehade R, Boldt RG, Raphael J, Blanchette P, Maleki Vareki S, Fernandes R. Association between immune-related side effects and efficacy and benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;92:102134. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kijima T, Fukushima H, Kusuhara S, Tanaka H, Yoshida S, Yokoyama M, Ishioka J, Matsuoka Y, Numao N, Sakai Y, Saito K, Matsubara N, Yuasa T, Masuda H, Yonese J, Kageyama Y, Fujii Y. Association between the occurrence and spectrum of immune-related adverse events and efficacy of pembrolizumab in Asian patients with advanced urothelial cancer: multicenter retrospective analyses and systematic literature review. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2021;19(3):208–216.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato T, Tomiyama E, Koh Y, Matsushita M, Hayashi Y, Nakano K, Ishizuya YU, Wang C, Hatano K, Kawashima A, Ujike T, Kawasaki K, Morii E, Gotoh K, Eguchi H, Kiyotani K, Fujita K, Nonomura N, Uemura M. A potential mechanism of anticancer immune response coincident with immune-related adverse events in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(9):4875–4883. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, Homma C, Tachibana H, Fukuda H, Yoshida K, Iizuka J, Kobayashi H, Okumi M, Ishida H, Tanabe K. Association between immune-related adverse events and prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(6):355.e21–355.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labadie BW, Liu P, Bao R, Crist M, Fernandes R, Ferreira L, Graupner S, Poklepovic AS, Duran I, Maleki Vareki S, Balar AV, Luke JJ. BMI, irAE, and gene expression signatures associate with resistance to immune-checkpoint inhibition and outcomes in renal cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):386. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-02144-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda T, Ishihara H, Nemoto Y, Tachibana H, Fukuda H, Yoshida K, Takagi T, Iizuka J, Hashimoto Y, Ishida H, Kondo T, Tanabe K. Prognostic impact of immune-related adverse events in metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(10):735.e9–735.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martini DJ, Goyal S, Liu Y, Evans ST, Olsen TA, Case K, Magod BL, Brown JT, Yantorni L, Russler GA, Caulfield S, Goldman JM, Nazha B, Harris WB, Kissick HT, Master VA, Kucuk O, Carthon BC, Bilen MA. Immune-related adverse events as clinical biomarkers in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncologist. 2021;26(10):e1742–e1750. doi: 10.1002/onco.13868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, Lamine F, Maillard M, Fraga M, Shabafrouz K, Ribi C, Cairoli A, Guex-Crosier Y, Kuntzer T, Michielin O, Peters S, Coukos G, Spertini F, Thompson JA, Obeid M. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(9):563–580. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrelli F, Signorelli D, Ghidini M, Ghidini A, Pizzutilo EG, Ruggieri L, Cabiddu M, Borgonovo K, Dognini G, Brighenti M, De Toma A, Rijavec E, Garassino MC, Grossi F, Tomasello G. Association of steroids use with survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(3):546. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aldea M, Orillard E, Mansi L, Marabelle A, Scotte F, Lambotte O, Michot JM. How to manage patients with corticosteroids in oncology in the era of immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertrand A, Kostine M, Barnetche T, Truchetet ME, Schaeverbeke T. Immune related adverse events associated with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:211. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, Bedke J, Capitanio U, Dabestani S, Fernández-Pello S, Giles RH, Hofmann F, Hora M, Klatte T, Kuusk T, Lam TB, Marconi L, Powles T, Tahbaz R, Volpe A, Bex A. European Association of Urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2022 update. Eur Urol. 2022;82(4):399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Méjean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, Colas S, Beauval JB, Bensalah K, Geoffrois L, Thiery-Vuillemin A, Cormier L, Lang H, Guy L, Gravis G, Rolland F, Linassier C, Lechevallier E, Beisland C, Aitchison M, Oudard S, Patard JJ, Theodore C, Chevreau C, Laguerre B, Hubert J, Gross-Goupil M, Bernhard JC, Albiges L, Timsit MO, Lebret T, Escudier B. Sunitinib alone or after nephrectomy in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(5):417–427. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]