Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has become a major public health problem after the outbreak caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus. Great efforts to contain COVID-19 transmission have been applied worldwide. In this context, accurate and fast diagnosis is essential.

Methods

In this prospective study, we evaluated the clinical performance of three different RNA-based molecular tests – RT-qPCR (Charité protocol), RT-qPCR (CDC (USA) protocol) and RT-LAMP – and one rapid test for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies.

Results

Our results demonstrate that RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol is the most accurate diagnostic test among those evaluated, while oro-nasopharyngeal swabs are the most appropriate biological sample. RT-LAMP was the RNA-based molecular test with lowest sensitivity while the serological test presented the lowest sensitivity among all evaluated tests, indicating that the latter test is not a good predictor of disease in the first days after symptoms onset. Additionally, we observed higher viral load in individuals who reported more than 3 symptoms at the baseline. Nevertheless, viral load had not impacted the probability of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion

Our data indicates that RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol in oro-nasopharyngeal swabs samples should be the method of choice to diagnosis COVID-19.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, RT-LAMP, RT-qPCR, TR DPP® COVID-19 IgM/IgG Bio-Manguinhos, Accuracy

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 spread around the world causing a pandemic that significantly impacted public health and the economy [1]. Currently, there are vaccines against COVID-19 that reduce, but do not prevent, the risk of infection [2]. Furthermore, there is evidence that these vaccines can lose potency against SARS-CoV-2 variants, allowing the virus to escape from vaccine-induced antibody neutralization [3]. In this context, diagnosis is essential to the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, especially in healthcare workers, a group at higher risk of infection than the general population [4], [5].

Several protocols and commercial tests have been developed to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 virus infection [6]. Reverse transcription followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) is a molecular method widely used to detect viral RNA [7]. Studies have reported high accuracy of this method for SARS-CoV-2 detection, either performed using commercial kits or as part of in-house research [7], [8]. Despite being the test of choice for COVID-19 diagnosis, some studies have demonstrated false negative results when using this method with COVID-19 patients [9], [10]. Also, RT-qPCR tests require sophisticated equipment, highly trained personnel, expensive reagents and, are often carried out in central laboratories [7], [11].

Another nucleic-acid-based diagnostic method – which is easier, simpler, and faster than RT-qPCR – is reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) [12]. This latter test does not need complex laboratory infrastructure and has demonstrated promising results in SARS-CoV-2 detection [13], [14]. RT-LAMP has shown good performance, with accuracy equivalent to the RT-qPCR [15].

Yet other diagnostic tools are serological tests for detecting IgM, IgG or IgA antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 [16], [17], [18]. Among these serological tests, many point-of-care (PoC) tests were developed and are useful to screen populations for SARS-CoV-2 infection in epidemiological surveys [19]. Although some of these rapid tests have good performance [20], others have only performed moderately-well [21]. In addition, the time since the onset of symptoms, clinical severity, and the population profile assessed are factors that can impact test accuracy [21].

Although several studies have reported the performance of different SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests, there are few prospective studies assessing test performance in symptomatic healthcare professionals, a group at high risk for COVID-19. Furthermore, additional studies that evaluate different diagnostic methods in different settings contribute to generating the knowledge regarding the most appropriate and effective use and interpretation of these tests. Herein, we evaluated the performance of three different types of diagnostic test when used on healthcare workers that assist patients in different hospitals in the city of Belo Horizonte, in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Methods

Study population

Healthcare professionals presenting with suspected symptoms of COVID-19 were recruited (between September 2020 and April 2021) from three hospitals in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: (i) Hospital das Clínicas (HC) at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, (ii) Unidade de Pronto Atendimento (UPA) Centro-Sul, and (iii) Hospital Metropolitano Dr. Célio de Castro (HMDCC). These healthcare professionals were interviewed using the survey form presented at the Supplementary file 1. All healthcare professionals working in patient care that had no previous history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and presented at least one of the following symptoms within the previous 7 days: fever (equal or greater than 37.5 °C), cough (dry or productive), fatigue, dyspnea, sore throat, anosmia/hyposmia and/or ageusia was included in the study Pregnant women and volunteers participating in clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines were excluded (Supplementary file 2).

Study design

All participants were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR. To increase the accuracy of the diagnosis we used the Charité Institute protocol [7], and the CDC (USA) protocol [22] Real-Time qPCR Diagnosis. Samples were obtained by self-collection of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, or saliva at days 1, 3 and 5 after the day of the interview (referred to as D1, D3 and D5, respectively). Participants characterized as COVID-19 “cases” had at least one positive result for SARS-CoV-2 detection in at least one RT-qPCR protocol used. COVID-19 “non-cases” had negative results for all samples tested in all RT-qPCR protocols. The same samples used in the RT-qPCR tests were also evaluated by RT-LAMP. Participants were tested at D3 for the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies using the Bio-Manguinhos TR DPP® COVID-19IgM/IgG rapid test (Supplementary file 3).

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from the samples using the QIAmp® Viral RNA Kit (QIAGEN®, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA obtained was either used immediately in RT-qPCR or RT-LAMP or stored until use at − 80 °C.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection using RT-qPCR Charité and CDC (USA) protocols

For SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection using the Charité and CDC (USA) protocols, 5 μL of RNA was added to the GoTaq Probe RT-qPCR System Kit (Promega). Each reaction contained GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix with dUTP (10 μL), GoScript RT Mix for one step RT-qPCR (0.4 μL), sense and antisense primers (400 nM -Charité and 500 nM -CDC), probes (150 nM-Charité and 125 nM-CDC) and nuclease free water to a final volume of 20 μL. The amplification conditions were: 45 °C for 15 min, 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and hybridization at 60 °C for 1 min

For the Charité protocol, samples were considered positive for SARS-CoV-2 when the amplification of both the E gene and the human RNase P gene (RNaseP) were detected at or below the 37th cycle threshold and the 35th cycle, respectively. Samples negative for RNase P were considered invalid and repeated using RNA template obtained from a new extraction reaction.

For the CDC (USA) protocol, RNase P gene amplification was not evaluated, as the template quality had already been determined. Samples were considered as positive for SARS-CoV-2 detection when amplification of both N1 and N2 gene fragments were detected at or below Ct 37. The primers and probes sequences are given in Supplementary file 4.

Reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP)

RT-LAMP was performed according to the method described by Alves and coworkers [15]. SARS-CoV-2 RNA extracted from the infected cells (Inactivated samples of SARS-CoV-2 isolate HIAE-02: SARS-CoV-2/SP02/human/2020/BRA – GenBank accession number MT126808.1) of an in vitro culture was used as positive control. As an internal control, all samples were tested in another tube for the amplification of the human beta-actin gene using ACTB primers. The reactions were carried out at 65 °C for 40 min in Veriti™ thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A sample was considered positive for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 when the tubes for both the target gene (the E and N genes) and the internal control (the beta-actin gene) were yellow. When both the target and internal control tubes were pink, the result was invalid and repeated with RNA template obtained from a new extraction reaction. The primer sequences are given in Supplementary File 5.

Bio-manguinhos TR DPP® COVID-19 IgM/IgG

The rapid test for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibody detection was performed using the Bio-Manguinhos TR DPP® COVID-19 IgM/IgG -kit according to manufacturer's instructions. IgM and IgG reactivity values equal or above 30 were considered positive for the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. This test was carried out on D3.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of the samples classified as either cases or non-cases according to demographic, socioeconomic and health status indicators was analyzed, and associations between the results of the diagnostic tests and the latter variables were tested using either chi-square or Fisher's exact tests.

Diagnostic Test Accuracy (DTA) was evaluated using the most common measures of classification success: sensitivity (sn); specificity (sp); positive predictive value (PPV); negative predictive value (NPV); apparent prevalence (p) positive likelihood ratio (LR+), the negative likelihood ratio (LR-) and, finally, accuracy. The EpiR package version 2.0.39 [23] of the statistical software R version 4.1.2 [24] was used to compute from count data provided in a 2-by-2 contingency table. The confidence interval was calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method.

In forest plots, the Higgins’ I 2 of the heterogeneity was determined by subtracting the number of degrees of freedom from the Cochrane Q statistics, and then dividing the resulting value by the Cochrane Q statistics. Values between 30% and 60% indicate moderate heterogeneity, values between 50% and 90% indicate substantial heterogeneity, and values between 75% and 100% indicate considerable heterogeneity. Heterogeneity may be suspected if the between-study variation is greater than the within-study variation in the forest plot. The R packages EpiR, meta version 2.0.53 and 6.0 respectively, of the statistical software R version 4.1.2 were also used to calculate sensitivity and specificity, while the package forest was used to make the forest plot.

To evaluate the existence of any association between the number of symptoms reported by participants and either viral load or the probability of testing positive by molecular diagnosis, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) (version 1.3.9) [25] models were used. The composite symmetry (exchangeable) correlation structure was used, as it is the only one applicable to data from this study among those currently available in R. GEE generates consistent and asymptotically normal estimators, even with the poor specification of the correlation structure, while the variance of β is robustly estimated by the “sandwich” estimator. Tests and confidence intervals are based on Wald statistics. When the outcome was binary, the logit link function was used, and when it was numeric, the identity link function was used.

Results

Demographics and clinical features at baseline

A total of 166 healthcare professionals were considered for inclusion in the study. Two individuals had COVID-19 symptoms for more than seven days and another was unable to provide samples. Thus, 163 participants were eligible for the study. Of these, two were lost during follow-up due to inability to deliver samples (Supplementary file 3). The study population was 71% female, with a median age of 35. Overall, the positivity rate for COVID-19 in the study population was 59.6%. None of the participants required hospitalization due to COVID-19. No significant difference was observed in the percentage of positivity among the three health centers at which the participants worked, between genders or between specific age-groups ( Table 1). The most frequent symptoms reported by the participants were headache, myalgia, coryza and cough (Table 1). Participants with a COVID-19 diagnosis according to RT-qPCR were 5.10 and 5.19 times more likely to have loss of taste and smell, respectively, when compared to non-diseased individuals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at baseline.

| Characteristics | COVID-19 cases | Number (%) COVID-19 non-cases |

Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health centers | HC | 66 (69) | 39 (60) | 105 (65) | 0.42 |

| HMDCC | 26 (27) | 21 (32) | 47 (29) | ||

| UPA | 4 (4) | 5 (8) | 9 (6) | ||

| Total | 96 (59.6) | 65 (40.4) | 161 (100) | ||

| Age (Years) | Range 21–30 | 27 (28) | 45 (28) | 45 (28) | 0.98 |

| Range 31–40 | 45 (47) | 75 (47) | 75 (47) | ||

| Range 41–62 | 24 (25) | 41 (25) | 41 (25) | ||

| Total | 96 (59.6) | 65 (40.4) | 161 (100) | ||

| Gender | Male | 33 (34) | 46 (29) | 46 (29) | 0.071 |

| Woman | 63 (66) | 115 (71) | 115 (71) | ||

| Total | 96 (59.6) | 65 (40.4) | 161 (100) | ||

| Professional Category | Nurse Technician | 21 (22) | 17 (26) | 38 (24) | 0.148 |

| Nurse | 19 (20) | 17 (26) | 36 (22) | ||

| Physicians | 42 (44) | 17 (26) | 59 (37) | ||

| AOthers | 14 (15) | 14 (22) | 28 (17) | ||

| Total | 96 (59.6) | 65 (40.4) | 161 (100) | ||

| Symptoms | Fever > 37.5 | 34 (35) | 15 (23) | 49 (30) | 0.135 |

| Shortness of breath | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 5 (3) | 1.000 | |

| Nasal congestion | 25 (26) | 9 (14) | 34 (21) | 0.096 | |

| Coryza | 56 (59) | 44 (68) | 100 (62) | 0.300 | |

| Nausea | 6 (6) | 8 (12) | 14 (9) | 0.292 | |

| Diarrhea | 7 (7) | 12 (18) | 19 (12) | 0.057 | |

| Prostration | 8 (8) | 1 (2) | 9 (6) | 0.136 | |

| Tiredness | 17 (18) | 15 (23) | 32 (25) | 0.525 | |

| Chill | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 8 (5) | 1.000 | |

| Headache | 53 (55) | 38 (59) | 91 (57) | 0.805 | |

| Sore throat | 32 (33) | 31 (48) | 63 (39) | 0.095 | |

| Cough | 51 (53) | 34 (52) | 85 (53) | 1.000 | |

| Myalgia | 46 (48) | 27 (42) | 73 (45) | 0.525 | |

| Dysgeusia | 19 (20) | 3 (5) | 22 (14) | 0.012 | |

| Anosmia | 29 (30) | 5 (8) | 34 (21) | 0.001 | |

| BOther(s) | 28 (29) | 20 (31) | 48 (30) | 0.966 |

A -Professionals included in the study: Social workers, Chemical pharmacists, Physical therapists, Speech therapists, Nutritionists, Psychologists, Clinical analysis technicians, Pathology technicians, Pharmacy technicians.

B - Other symptoms reported by the healthcare professionals included: malaise, throat irritation, pain in the face, abdominal pain, inappetence, asthenia, arthralgia, retro orbital pain and sweating.

Performance evaluation of RNA-based and serological diagnostic tests

The performance of the RT-qPCR protocols, RT-LAMP and the TR DPP® COVID-19 IgM/IgG test is demonstrated at Table 2. RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol had the best performance regardless of the biological sample used (Table 2). The use of saliva samples in all RNA-based molecular tests resulted in a lower accuracy compared to tests that used oro-nasopharyngeal swab samples (Table 2). The serological test was the least accurate regardless of the antibody class detected (either IgM or IgG) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Performance indicators of the diagnostic tests for COVID19 applied to symptomatic healthcare professionals.

| Diagnostic tests | COVID-19§ | PERFORMANCE INDICATORS value (lower-upper limits of the 95% CI) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p * | Sn | sp | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR- | Accuracy | |

| RNA-based molecular tests (Overall)# | ||||||||||

| RT-qPCR CDC (USA) + - |

94 2 |

0 65 |

0.58 (0.50–0.66) | 0.98 (0.93–1.00) |

1.00 (0.94–1.00) |

1.00 (0.96–1.00) |

0.97 (0.90–1.00) |

Inf. | 0.02 (0.01–0.08) |

0.99 (0.96–1.00) |

| RT-qPCR Charité + - |

57 39 |

0 65 |

0.35 (0.28–0.43) |

0.59 (0.49–0.69) |

1.00 (0.94–1.00) |

1.00 (0.94–1.00) |

0.65 (0.52–0.72) |

Inf. | 0.41 (0.32–0.52) |

0.76 (0.68–0.82) |

| RT-LAMP + - |

53 43 |

7 58 |

0.37 (0.30–0.45) |

0.55 (0.45–0.65) |

0.89 (0.79–0.96) |

0.88 (0.770.95) |

0.57 (0.47–0.67) |

5.13 (2.49 −10.56) |

0.50 (0.40–0.64) |

0.69 (0.61–0.76) |

| RNA-based molecular tests * * (Saliva) | ||||||||||

| RT-qPCR CDC (USA) + - |

60 2 |

0 41 |

0.58 (0.48–0.68) |

0.97 (0.89–1.00) |

1.00 (0.91–1.00) |

1.00 (0.94–1.00) |

0.95 (0.84–0.99) |

Inf. | 0.03 (0.01–0.13) |

0.98 (0.93–1.00) |

| RT-qPCR Charité + - |

33 29 |

0 41 |

0.32 (0.23–0.42) |

0.53 (0.40–0.66) |

1.00 (0.91–1.00) |

1.00 (0.89–1.00) |

0.59 (0.46–0.70) |

Inf. | 0.47 (0.36–0.61) |

0.72 (0.62–0.80) |

| RT-LAMP + - |

28 34 |

5 36 |

0.32 (0.23–0.42) |

0.45 (0.32–0.58) |

0.88 (0.74–0.96) |

0.85 (0.68–0.95) |

0.51 (0.39–0.64) |

3.70 (1.56–8.80) |

0.62 (0.48–0.80) |

0.62 (0.52–0.72) |

| RNA-based molecular tests * ** (Swab) | ||||||||||

| RT-qPCR CDC (USA) + - |

34 0 |

0 24 |

0.59 (0.45–0.71) |

1.00 (0.90–1.00) |

1.00 (0.86–1.00) |

1.00 (0.90–1.00) |

1.00 (0.86–1.00) |

Inf | Inf | 1.00 (0.941.00) |

| RT-qPCR Charité + - |

24 10 |

0 24 |

0.41 (0.29–0.55) |

0.71 (0.53–0.85) |

1.00 (0.86–1.00) |

1.00 (0.86–1.00) |

0.71 (0.53–0.85) |

Inf | 0.29 (0.17–0.50) |

0.83 (0.71–0.91) |

| RT-LAMP + - |

25 9 |

2 22 |

0.47 (0.33–0.60) |

0.74 (0.56–0.87) |

0.92 (0.73–0.99) |

0.93 (0.76–0.99) |

0.71 (0.52–0.86) |

8.82 (2.31–33.77) |

0.29 (0.16–0.51) |

0.81 (0.69–0.90) |

| Serological tests* ** * | ||||||||||

| TR IgM + - |

18 78 |

1 64 |

0.12 (0.07–0.18) |

0.19 (0.12–0.28) |

0.98 (0.92–1.00) |

0.95 (0.74–1.00) |

0.45 (0.37–0.54) |

12.19 (1.67–89.06) |

0.83 (0.75–0.91) |

0.51 (0.43–0.59) |

| TR IgG + - |

35 60 |

13 52 |

0.30 (0.23–0.38) |

0.37 (0.27–0.47) |

0.80 (0.68–0.89) |

0.73 (0.58–0.85) |

0.46 (0.37–0.56) |

1.84 (1.06–3.20) |

0.79 (0.65–0.96) |

0.54 (0.46–0.62) |

§ Participants were classified as COVID-19 cases if they had at least one positive result in the RT-qPCR test (regardless of the particular protocol and sample type used).

# RNA-based molecular tests performed using saliva and swabs collected samples.

** RNA-based molecular tests performed using saliva collected samples.

*** RNA-based molecular tests performed using swab collected samples.

**** Bio-Manguinhos TR DPP® COVID-19 IgM/IgG Kit.

p * = apparent prevalence; sn = sensitivity; sp = specificity; PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value; LR+ = Positive Likelihood Ratio; LR- = Negative likelihood ratio; accuracy = proportion of correctly classified participants; Inf.: estimate tends to infinity.

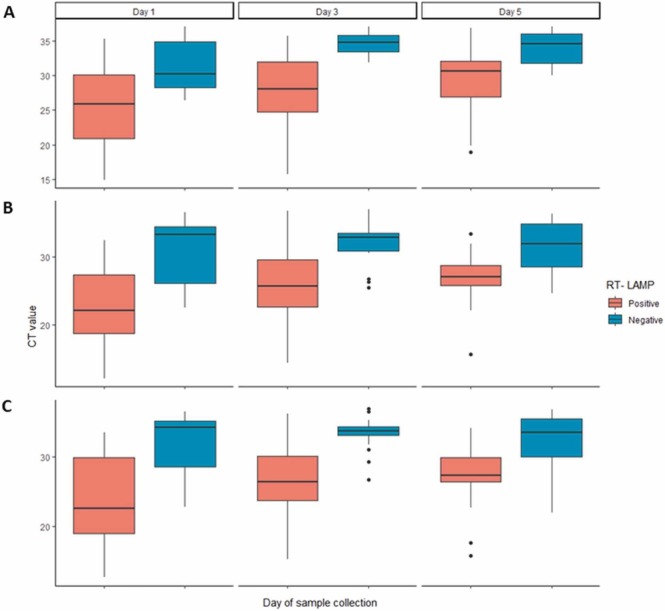

The sensitivity and specificity among all tests and sample types analyzed in this study were compared using a random effects model ( Fig. 1). Among the RNA-based molecular tests applied to saliva samples (g1), only the RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol had sensitivity values higher than the mean sensitivity value calculated for all the tests and samples analyzed together (Fig. 1A). In the saliva sample group, the data distribution for sensitivity is highly heterogeneous. When the random effects model was applied to the results observed in oro-nasopharyngeal swab samples (g2), higher sensitivity values were observed for all the RNA-based molecular tests when compared to the results observed when using the saliva samples (Fig. 1A). Once again, the RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol had the highest sensitivity value, but RT-LAMP also showed a sensitivity value higher than the mean sensitivity value of all the tests and samples combined (Fig. 1A). RT-LAMP correctly classified as SARS-CoV-2 positive samples with lower Ct values for the E gene ( Fig. 2A), and the N1 (Fig. 2B) and N2 gene fragments (Fig. 2C). Although the data obtained in serological tests had low heterogeneity, these tests had sensitivity values below the mean sensitivity values calculated for all tests analyzed together (Fig. 1A). High specificity values were observed for all tests and for all sample types (Fig. 1B), but specificity values for RT-LAMP using either saliva or swabs, and the serological test for detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG were lower than the mean specificity value calculated for all tests and samples analyzed together (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Estimation of the sensitivity and specificity of the different diagnostic tests and biological samples. The diagnostic tests are grouped according to the type of biological sample tested: saliva (g1); oro-nasopharyngeal swab (g2) and sera (g3). The number of positive samples (events) and of samples tested (total) are presented in the table. The “Proportion” column shows the sensitivity (A) and specificity (B) values and the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval. Horizontal lines represent the mean and ranges of the 95% CI for sensitivity (A) and specificity (B) of each individual test/sample type combination performed. The vertical dashed lines represent either the global average of sensitivity (A) or specificity (B). Diamonds represent the distribution of the data for each group of tests pooled.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of RT-LAMP and RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection. Box plots represents the CT value obtained for each of the three different RT-qPCR targets: E gene (A), N1 gene fragment (B) or the N2 gene fragment (C) in samples presenting positive (orange) or negative (blue) results in the RT-LAMP test. Data are grouped along the x-axis according to the day of sample collection.

Supplementary file 1: Survey form used to interview healthcare professionals.

Supplementary file 2: Flowchart for the verification of the eligibility criteria.

Supplementary File 3. Study workflow. Workflow illustrating the study design. One-hundred and sixty-three participants were enrolled in the study (Day 0). Two participants were lost during follow-up before collection of the first sample on Day 1. RNA-based tests were performed using saliva or naso and oropharyngeal swabs collected at Days 1, 3 and 5. A rapid test to detect anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies was performed on day 3. Participants with at least one SARS-CoV-2 positive sample in any RT-qPCR protocol were considered COVID-19 cases.

Assessment of the impact of multiple testing and number of symptoms on the diagnosis outcome

The World Health Organization recommends repeated RT-qPCR testing upon negative results, especially in the presence of COVID-19 symptoms [26]. We calculated the sensitivity achieved when either one, two or three different biological samples were tested and when both the RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP methods were used on the same sample. In general, we observed an increase in sensitivity as the number of samples analyzed increased. However, the use of the CDC (USA) RT-qPCR protocol, even with only one sample, had a higher sensitivity than using either two or three samples and either the Charité RT-qPCR protocol or RT-LAMP tests ( Table 3). Using the combination of both RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP for the diagnosis of COVID-19 resulted in only a small increase in sensitivity (Table 3). To understand the impact of the number of symptoms on the likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19, the outcome of the molecular diagnostic tests according to the number of symptoms and day of follow-up was analyzed. The likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19 by the three RNA-based molecular tests is not, in general, affected by the number of symptoms reported by the participant ( Table 4). However, a decreased probability of testing positive by the Charité RT-qPCR protocol or RT-LAMP was observed during the D5 follow up (Table 4).

Table 3.

Sensitivity for one-sample tests and multiple-sample retests using RNA-base molecular diagnosis to detect SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare professionals.

| mean sensitivity (%) (lower-upper limit of the 95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR CDC (USA) | RT-qPCRCharité | RT-LAMP | RT-qPCR CDC (USA) + RT-LAMP |

RT-qPCRCharité + RT-LAMP |

||

| One sample | (D1 or D3 or D5) | 75.61 (62.39–88.83) |

45.42 (30.39–60.46) |

37.73 (19.55–55.90) |

76.19 (59.74–92.65) |

50.18 (32.01–68.36) |

| Two samples | (D1 +D3 or D1 +D5 or D3 +D5) | 88.64 (84.47–92.81) |

57.51 (49.63–65.39) |

51.28 (44.98–57.59) |

___ | ___ |

| Three samples | (D1 + D3 + D5) | 98.90 | 59.34 | 57.14 | ___ | ___ |

Table 4.

Impact of day of follow-up and number of symptoms on the likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR (Charité) | ||

| Follow-up day | ||

| D1 | ------ | |

| D3 | 0.947 (0.726; 1.235) | 0.689 |

| D5 | 0.685 (0.496; 0.945) | 0.021a |

| Number of symptoms | ||

| ≤ 2 | ------ | |

| 3–4 5–6 ≥ 7 |

3.559 (0.77; 16.444) 3.309 (0.698; 15.681) 4.216 (0.78; 22.777) |

0.104 0.132 0.095 |

| RT-qPCR (CDC (USA)) | ||

| Follow-up day | ||

| D1 | ------ | |

| D3 | 1.11 (0.884; 1.393) | 0.368 |

| D5 | 0.764 (0.578; 1.01) | 0.058 |

| Number of symptoms | ||

| ≤ 2 | ------ | |

| 3–4 5–6 |

1.571 (0.527; 4.679) 1.872 (0.607; 5.767) |

0.417 0.275 |

| ≥ 7 | 3.107 (0.805; 12.00) | 0.1 |

| RT-LAMP | ||

| Follow up days | ||

| D1 | ------ | |

| D3 | 0.836 (0.524; 1.334) | 0.453 |

| D5 | 0.561 (0.318; 0.988) | 0.045a |

| Number of symptoms | ||

| ≤ 2 | ------ | |

| 3–4 5–6 |

2.962 (0.717; 12.237) 2.838 (0.678; 11.878) |

0.134 0.153 |

| ≥ 7 | 2.347 (0.532; 10.364) | 0.26 |

p < 0.05

Association between viral load and symptoms numbers

A significant decrease in the Ct value (i.e., higher viral loads) was observed in participants with more than 3 symptoms reported at baseline for all target genes at D1 and D3, except for the N2 gene fragment and the E gene at D3 for participants with 5–6 or more than seven symptoms, respectively ( Table 5). At D5, a significant decrease in Ct values was only observed for the E gene and the N2 gene fragment in participants with 3 or 4 reported symptoms (Table 5). No correlation was observed between antibody levels and viral load (data not shown).

Table 5.

Association between the number of symptoms reported at baseline and viral load.

| Days after inclusion in the study Ct units (lower-upper limits of the 95% CI) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D3 | D5 | |||||||

| Number of Symptoms/ Test (Target gene) |

RT-qPCR -Charité (E) |

RT-qPCR –CDC (USA) (N1) |

RT-qPCR –CDC (USA) (N2) |

RT-qPCR -Charité (E) |

RT-qPCR –CDC (USA) (N1) |

RT-qPCR –CDC (USA) (N2) |

RT-qPCR -Charité (E) |

RT-qPCR –CDC (USA) (N1) |

RT-qPCR –CDC (USA) (N2) |

| ≤ 2 (n = 18) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| 3–4 (n = 81) | -5.35 * ** (−8.30; −2.41) |

-3.74 * * (−6.53; −0.94) |

-7.50 * ** (−10.90; −4.07) |

-5.70 * ** (−8.43; −2.98) |

-3.67 * * (−6.32; −1.01) |

-4.58 * ** (−7.37; −1.78) |

-4.72 * ** (−7.01; −2.42) |

-2.32 (−4.81; 0.16) |

-6.24 * ** (−9.46; −3.02) |

| 5–6 (n = 48) | -4.05 * (−7.26; −0.83) |

-3.43 * (−6.49; −0.37) |

-4.86 * * (−8.37; −1.35) |

-3.79 * * (−6.56; −1.01) |

-3.10 * (−5.86; −0.33) |

-2.99 (−6.00; 0.03) |

-1.60 (−3.62; 0.422) |

-1.78 (−4.41; 0.86) |

-2.24 (−5.57; 1.09) |

| ≥ 7 (n = 14) | -6.94 * * (−12.20; 1.68) |

-6.26 * * (−10.70; −1.86) |

-9.63 * ** (−14.30; −4.96) |

-2.7 (−6.24; 0.849) |

-4.04 * (−7.37; −0.70) |

-3.93 * (−7.26; −0.60) |

-0.46 (−2.95; 2.03) |

-1.53 (−4.46; 1.41) |

-1.51 (−5.22; 2.19) |

* p < 0.05, * * p < 0.01, * ** p < 0.001

Discussion

Accurate diagnosis is an important tool to control SARS-CoV-2 spread [26]. The current prospective study focused on evaluating the performance of different diagnostic tests on healthcare professionals from Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Our study population was mainly composed of participants with 31–40 years-old, with females representing 71% of the participants. We detected 59.6% positivity in our cohort, more than 2-fold higher than the 20% COVID-19 positivity rate in healthcare professionals reported in Belo Horizonte in the recruitment period [27], [28]. This higher positivity rate might be due to the use of two different RT-qPCR protocols CDC (USA) and Charité) for the determination of disease status. Anosmia and dysgeusia were most prevalent among COVID-19 cases, corroborating other studies that also reported that these symptoms are associated with COVID-19 [29], [30].

Herein, we evaluated the clinical performance of three different RNA-based molecular tests, as well as the rapid test from Bio-Manguinhos for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies. RT-qPCR is the most used test in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 [6], [7], [22]. However, RT-qPCR assays that target different fragments of either the same or different viral genes may vary in their level of test performance [8], [31]. In our cohort, the RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol had the best performance. The N gene, targeted by the CDC (USA) RT-qPCR protocol, has been reported to be the most abundant transcript of SARS-CoV-2 [32] and this may have impacted test performance.

Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the sample type also impacts the sensitivity of diagnostic tests for COVID-19. The most appropriate biological sample for detection of SARS-CoV-2 is still controversial [33], [34]. Our data demonstrate that higher sensitivity is achieved when oro-nasopharyngeal swabs are used, regardless of test used. In addition, greater heterogeneity in the distribution of sensitivity and specificity was observed in the random effect model when saliva samples were analyzed in the molecular tests, reinforcing the belief that oro-nasopharyngeal swabs are the best choice of biological sample to be used in molecular tests for COVID-19. We observed high specificity values for both RT-qPCR protocols evaluated, but these results must be carefully interpreted, as participants had their disease status determined based on a positive result in at least one biological sample using either of the RT-qPCR protocols.

Despite having high specificity, RT-LAMP had the lowest sensitivity among RNA-based molecular tests evaluated. Previous studies have demonstrated that RT-LAMP has limited sensitivity to detect infection in individuals with low viral loads [15], [35], while samples with a RT-qPCR Ct value lower than 30 are correctly identified as positive by RT-LAMP [15]. Our results corroborate this observation, since samples with Ct values lower than 33 were correctly diagnosed by the RT-LAMP.

A recent meta-analysis showed that combining the results from RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP enables sensitivity and specificity higher than 90% [36]. A relevant increase in sensitivity when using this approach was not observed in our study, and the test and retest approach showed more success in accurate diagnosis of COVID-19. Pu and co-workers [36] also reported a high diagnostic value for RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP, as suggested by the positive and negative likelihood values (LR+ and LR-) observed in their meta-analysis. In our study, all evaluated tests had LR+ values higher than 1, and LR- values lower than 1. Of note is that in our study RT-qPCR had LR+ values that tended to infinity and the lowest LR- values.

Regarding the serological tests, low sensitivity was observed for both IgM and IgG detection. Therefore, such test is not a good predictor of disease diagnosis in the first days after symptom onset. Our data corroborate previous studies that report that IgM and IgG seroconversion, in general, occurs 10 days after symptom onset [37], [38].

The cycle threshold (Ct) values observed in RT-qPCR has been used as an indirect (i.e., relative) indicator of viral load, as the Ct value is inversely proportional to the amount of viral material present in the sample [38], [39]. Marks et al. (2021) identified a positive association between viral load and the presence of fever, risk of disease transmission, and increased risk of developing symptoms [39]. In our study, we observed higher viral loads (i.e., lower Ct values) in individuals who reported more than 3 symptoms at baseline, suggesting a positive association between the number of symptoms and viral load. Despite this, in our cohort the number of symptoms reported at baseline did not influence the outcome of the RNA based molecular diagnostic tests. Thus, molecular tests are still an important tool, even in the current epidemiological scenario, where COVID-19 vaccines are responsible for preventing and/or considerably reducing the symptoms experienced with infection by SARS-CoV-2 [40].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data indicate RT-qPCR using the CDC (USA) protocol and oro-nasopharyngeal swabs as the most appropriate to conduct COVID-19 diagnostic test. In individuals with mild COVID-19, the number of symptoms did not impact the chance of testing positive for COVID-19, although it seems to be associated with viral load.

Study limitations

RT-qPCR using CDC (USA) and Charité protocols were used in combination to determine disease status, thus specificity values observed for these tests when applied separately might have been overestimated. Our study population is composed only of symptomatic individuals, therefore the accuracy of the tests in asymptomatic individuals was not assessed. Only non-severe cases of COVID-19 were observed in our study cohort, so the performance of the diagnostic tests for people suffering severe illness was not evaluated. Symptom intensity was also not assessed, so the number of symptoms was the only available measurement to stratify the population according to clinical data.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2023.05.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Jackson J.K., Weiss Martin A., Schwarzenberg A.B., Rebecca M.N., Sutter K.M., Sutherland M.D. Global Economic Effects of COVID-19 2021. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46270.pdf (accessed September 3, 2022).

- 2.Fan Y.-J., Chan K.-H., Hung I.F.-N. Safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis of different vaccines at Phase 3. Vaccines. 2021:9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Beltran W.F., Lam E.C., St, Denis K., Nitido A.D., Garcia Z.H., Hauser B.M., et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell. 2021;184:2372–2383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.013. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai X., Wang M., Qin C., Tan L., Ran L., Chen D., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a Tertiary Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt Fernandes F., de Castro Cardoso Toniasso S., Castelo Branco Leitune J., Borba Brum M.C., Bielefeldt Leotti V., Dantas Filho F.F., et al. COVID-19 among healthcare workers in a Southern Brazilian Hospital and evaluation of a diagnostic strategy based on the RT-PCR test and retest for Sars-CoV-2. Eur Rev Med Pharm Sci. 2021;25:3365–3374. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202104_25748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FIND. SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic pipeline 2021. www.finddx.org/covid19/pipeline (Accessed September 26, 2021).

- 7.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eur Surveill. 2020:25. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Kasteren P.B., van der Veer B., van den Brink S., Wijsman L., de Jonge J., van den Brandt A., et al. Comparison of seven commercial RT-PCR diagnostic kits for COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;128 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., Zhan C., Chen C., Lv W., et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296:E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D., Wang D., Dong J., Wang N., Huang H., Xu H., et al. False-negative results of real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: ROle of Deep-learning-based CT diagnosis and insights from two cases. Korean J Radio. 2020;21:505–508. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bustin S.A., Benes V., Garson J.A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., et al. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notomi T., Okayama H., Masubuchi H., Yonekawa T., Watanabe K., Amino N., et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28 doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb L.E., Bartolone S.N., Ward E., Chancellor M.B. Rapid detection of novel coronavirus/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagura-Ikeda M., Imai K., Tabata S., Miyoshi K., Murahara N., Mizuno T., et al. Clinical evaluation of self-collected saliva by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR), direct RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-loop-mediated isothermal amplification, and a rapid antigen test to Diagnose COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol. 2020:58. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01438-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alves P.A., de Oliveira E.G., Franco-Luiz A.P.M., Almeida L.T., Gonçalves A.B., Borges I.A., et al. Optimization and clinical validation of colorimetric reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification, a fast, highly sensitive and specific COVID-19 molecular diagnostic tool that is robust to detect SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Front Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.713713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Marinis Y., Sunnerhagen T., Bompada P., Bläckberg A., Yang R., Svensson J., et al. Serology assessment of antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19 by rapid IgM/IgG antibody test. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2020;10:1821513. doi: 10.1080/20008686.2020.1821513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller T.E., Garcia Beltran W.F., Bard A.Z., Gogakos T., Anahtar M.N., Astudillo M.G., et al. Clinical sensitivity and interpretation of PCR and serological COVID-19 diagnostics for patients presenting to the hospital. FASEB J. 2020;34:13877–13884. doi: 10.1096/fj.202001700RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Psichogiou M., Karabinis A., Pavlopoulou I.D., Basoulis D., Petsios K., Roussos S., et al. Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers in a country with low burden of COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hengel B., Causer L., Matthews S., Smith K., Andrewartha K., Badman S., et al. A decentralised point-of-care testing model to address inequities in the COVID-19 response. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:e183–e190. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30859-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J.-L., Tseng W.-P., Lin C.-H., Lee T.-F., Chung M.-Y., Huang C.-H., et al. Four point-of-care lateral flow immunoassays for diagnosis of COVID-19 and for assessing dynamics of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020;81:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cota G., Freire M.L., de Souza C.S., Pedras M.J., Saliba J.W., Faria V., et al. Diagnostic performance of commercially available COVID-19 serology tests in Brazil. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/download (Accessed November 8, 2021).

- 23.Stevenson M., Sergeant E., Nunes T., Heuer C., Marshall J., Sanchez J., et al. Tools for the Analysis of Epidemiological Data. R package version 2.0.39 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=epiR (accessed October 8, 2022).

- 24.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria 2022. https://www.R-project.org/. (Accessed October 17, 2022).

- 25.Højsgaard S., Halekoh U., Yan J. The R Package geepack for Generalized Estimating Equations Journal of Statistical 2006.

- 26.WHO. Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in suspected human cases: interim guidance. 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331501 (Accessed September 4, 2022).

- 27.Boletim epidemiológico assistencial 2020. https://prefeitura.pbh.gov.br/sites/default/files/estrutura-de-governo/saude/2020/boletim_epidemiologico_assistencial_115_covid-19_30–09-2020.pdf. (Accessed June 21, 2022).

- 28.Boletim epidemiológico assistencial COVID19 2021. https://prefeitura.pbh.gov.br/sites/default/files/estrutura-de-governo/saude/2021/boletim_epidemiologico_assistencial_252_covid-19_20–04-2021.pdf (Accessed June 21, 2022).

- 29.Lan F.-Y., Filler R., Mathew S., Buley J., Iliaki E., Bruno-Murtha L.A., et al. COVID-19 symptoms predictive of healthcare workers’ SARS-CoV-2 PCR results. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., de Siati D.R., Horoi M., le Bon S.D., Rodriguez A., et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:2251–2261. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang D., Wang Z., Gao Y., Wu X., Dong L., Dai X., et al. Validation of the analytical performance of nine commercial RT-qPCR kits for SARS-CoV-2 detection using certified reference material. J Virol Methods. 2021;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim D., Lee J.-Y., Yang J.-S., Kim J.W., Kim V.N., Chang H. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell. 2020;181(914–921) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Defêche J., Azarzar S., Mesdagh A., Dellot P., Tytgat A., Bureau F., et al. In-depth longitudinal comparison of clinical specimens to detect SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens. 2021:10. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10111362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kritikos A., Caruana G., Brouillet R., Miroz J.-P., Abed-Maillard S., Stieger G., et al. Sensitivity of rapid antigen testing and RT-PCR performed on nasopharyngeal swabs versus saliva samples in COVID-19 hospitalized patients: results of a prospective comparative trial (RESTART) Microorganisms. 2021:9. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9091910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dao Thi V.L., Herbst K., Boerner K., Meurer M., Kremer L.P., Kirrmaier D., et al. A colorimetric RT-LAMP assay and LAMP-sequencing for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in clinical samples. Sci Transl Med. 2020:12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc7075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pu R., Liu S., Ren X., Shi D., Ba Y., Huo Y., et al. The screening value of RT-LAMP and RT-PCR in the diagnosis of COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Virol Methods. 2022;300 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grzelak L., Temmam S., Planchais C., Demeret C., Tondeur L., Huon C., et al. A comparison of four serological assays for detecting anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in human serum samples from different populations. Sci Transl Med. 2020:12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.To K.K.-W., Tsang O.T.-Y., Leung W.-S., Tam A.R., Wu T.-C., Lung D.C., et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marks M., Millat-Martinez P., Ouchi D., Roberts C. h, Alemany A., Corbacho-Monné M., et al. Transmission of COVID-19 in 282 clusters in Catalonia, Spain: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:629–636. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30985-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Robertson C., Stowe J., Tessier E., et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material