Key Points

Question

Does mitochondrial dysfunction underlie altered skeletal muscle metabolism and exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study including 27 patients older than 60 years with HFpEF and 45 healthy age-matched controls, high-resolution respirometry of vastus lateralis muscles from patients with HFpEF revealed markedly reduced bioenergetic capacity associated with peak exercise oxygen consumption and exercise performance (6-minute walk distance, Short Physical Performance Battery, and leg strength).

Meaning

In this study, detailed analysis of mitochondrial function provided evidence that skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction can play a role in HFpEF exercise intolerance, which may impact the development of therapeutic strategies that target mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with HFpEF.

This cross-sectional study evaluates the associations of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function using respirometric analysis of biopsied muscle fiber bundles from patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) with exercise performance.

Abstract

Importance

The pathophysiology of exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) remains incompletely understood. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that abnormal skeletal muscle metabolism is a key contributor, but the mechanisms underlying metabolic dysfunction remain unresolved.

Objective

To evaluate the associations of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function using respirometric analysis of biopsied muscle fiber bundles from patients with HFpEF with exercise performance.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional study, muscle fiber bundles prepared from fresh vastus lateralis biopsies were analyzed by high-resolution respirometry to provide detailed analyses of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, including maximal capacity and the individual contributions of complex I–linked and complex II-linked respiration. These bioenergetic data were compared between patients with stable chronic HFpEF older than 60 years and age-matched healthy control (HC) participants and analyzed for intergroup differences and associations with exercise performance. All participants were treated at a university referral center, were clinically stable, and were not undergoing regular exercise or diet programs. Data were collected from March 2016 to December 2017, and data were analyzed from November 2020 to May 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Skeletal muscle mitochondrial function, including maximal capacity and respiration linked to complex I and complex II. Exercise performance was assessed by peak exercise oxygen consumption, 6-minute walk distance, and the Short Physical Performance Battery.

Results

Of 72 included patients, 50 (69%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 69.6 (6.1) years. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial function measures were all markedly lower in skeletal muscle fibers obtained from patients with HFpEF compared with HCs, even when adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index. Maximal capacity was strongly and significantly correlated with peak exercise oxygen consumption (R = 0.69; P < .001), 6-minute walk distance (R = 0.70; P < .001), and Short Physical Performance Battery score (R = 0.46; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, patients with HFpEF had marked abnormalities in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Severely reduced maximal capacity and complex I–linked and complex II–linked respiration were associated with exercise intolerance and represent promising therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is the most prevalent form of HF, particularly among older adults and women.1,2 As our population continues to get older, the prevalence of HFpEF is increasing,3,4 as are risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.5,6

The primary clinical manifestation of chronic stable HFpEF is severe exercise intolerance, which is associated with impaired quality of life, and can be measured objectively and reproducibly as reduced peak exercise oxygen uptake (peak VO2).7,8,9,10 However, the pathophysiology of exercise intolerance is incompletely understood, and there are few effective therapies. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that in addition to underlying cardiac dysfunction, noncardiac factors contribute to exercise intolerance in HFpEF.9,11,12 Our group and others reported that reduced cardiac output accounts for only approximately 50% of the reduced peak VO2 in patients with HFpEF,9,13 supporting a role for peripheral factors. Endurance exercise training significantly improves peak VO2 in clinically stable older patients with HFpEF, with most of the improvement mediated by noncardiac factors, such as skeletal muscle function.14,15 Altogether, these studies suggest that skeletal muscle alterations significantly contribute to exercise intolerance in patients with HFpEF.

Several lines of evidence indicate that skeletal muscle metabolism is impaired in patients with HFpEF.12 While patients with HFpEF have a lower lean mass, the increase in VO2 during exercise relative to lean mass is lower in those with HFpEF compared with healthy controls (HCs), suggesting intrinsic metabolic differences.16 We have reported that older patients with HFpEF have abnormal skeletal muscle oxygen utilization that is associated with severely reduced peak VO2.16 Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy, Weiss et al17 reported reduced skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism and its relation to muscle fatigue. Further, Dhakal et al,13 using hemodynamic monitoring during exercise, showed that oxygen extraction was significantly reduced in HFpEF and is a major contributor to reduced peak VO2.

Examination of skeletal muscle biopsies has shown that patients with HFpEF have a decreased number of type I oxidative fibers.18 Patients with HFpEF have lower vastus lateralis mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity as reported by citrate synthase activity and the expression of mitochondrial structural proteins.19 The significant associations of these parameters with measures of exercise capacity support that these deficits may contribute to severely reduced exercise capacity. Additionally, we observed that the mitochondrial fusion regulator, mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), is significantly decreased in HFpEF skeletal muscle and may also contribute to exercise intolerance. Importantly, these mitochondrial parameters were directly related to peak VO2 and 6-minute walk distance.

Despite evidence suggesting multifaceted skeletal muscle mitochondrial impairments, respirometric analyses of skeletal muscle tissue, the criterion-standard assessment of mitochondrial function, in the context of HFpEF are lacking. Using a rat model of HFpEF, Bowen et al20 reported impaired mitochondrial respiration that was ameliorated with exercise training. More recently, skeletal muscle maximal mitochondrial respiration was found to be 40% to 55% lower in a postmenopausal rat model of HFpEF compared with controls.21 This was accompanied by a 15% to 30% decrease in specific force generation, suggesting a role for mitochondrial abnormalities in skeletal myopathy.

To elucidate the role of mitochondria in impaired skeletal muscle metabolism in patients with HFpEF, the study presented here used high-resolution respirometry of freshly obtained skeletal muscle specimens to provide detailed analyses of mitochondrial function, including precise assessments of the maximal capacity of the electron transfer system and the individual contributions of complex I–linked and complex II–linked respiration. These bioenergetic data were then associated with key measures of exercise performance across HFpEF and age-matched HC participants.

Methods

Participants

Participants with HFpEF were selected based on detailed inclusion criteria, as described previously7,9,15,22,23,24 and in accord with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommendations current at the time of study design.25 HFpEF was defined as symptoms and signs of HF and preserved resting left ventricular systolic function (50% or greater), left ventricular diastolic dysfunction of grade 1 or higher, and body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 28 or greater. HF signs and symptoms were confirmed by a board-certified cardiologist and met the criteria of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey HF clinical score of 3 or higher and the criteria of Rich et al.26,27 Exclusions included significant ischemic or valvular heart disease, pulmonary disease, anemia, or other disorder that could explain the patients’ symptoms.7,9,23 Given the strong age dependence of HFpEF, patients and controls were 60 years and older at study entry. Participants in this study were drawn from a parent clinical trial of patients with HFpEF. The results of that trial, including a detailed description of the study participants, have been published.28

Age-matched, healthy, sedentary persons were recruited to serve as HCs. Potential HCs were excluded if they had chronic medical illness, were taking chronic medications other than preventive low-dose aspirin, had abnormal findings on physical examination (including blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher), had abnormal results on the screening tests (including electrocardiography, exercise echocardiography, and spirometry), or regularly undertook vigorous exercise.16,29 The protocol for this study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Exercise Performance

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing was performed on a treadmill using the modified Naughton protocol for patients with HFpEF and using the modified Bruce protocol for HCs, as previously described.7,24,30 Expired gas analysis was conducted using a commercially available system (CPX-2000 and Ultima; MedGraphics), calibrated before each test with a standard gas of known concentration and volume. Breath-by-breath gas exchange data were measured continuously during exercise and averaged every 15 seconds, and peak values were averaged from the last two 15-second intervals during peak exercise.

A 6-minute walk test was performed using the method of Guyatt et al.31 The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) consists of a usual gait speed test, a usual gait speed test using a narrow course (20 cm), 5 repeated chair stands, and a 30-second standing balance tests (side-by-side, semitandem, and full tandem).32,33 Each component is scored on a scale of 0 to 4 for a total score of 0 to 12, with a higher score indicating better physical function.

Peak upper leg strength (in newton meters) was measured on a dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems) at 60° per second, with the participant seated and the hips and knees flexed at 90°. To stabilize the hip joint and the trunk, participants were secured with straps at the chest, hip, and thigh. Seat height and depth, and the position of the lever arm ankle pad were adjusted to accommodate each participant. Participants were asked to extend the knee and push as hard as possible against the ankle pad. Strength of the right and left legs recorded as peak torque was used for analyses.

Skeletal Muscle Biopsy

Vastus lateralis biopsies were performed in the morning after an overnight fast, as previously described.18,34,35 Participants were asked to refrain from taking aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other compounds that may affect bleeding, platelets, or bruising for the week prior to the biopsy and to refrain from strenuous activity for 36 hours prior to biopsy. Muscle was obtained from the vastus lateralis by percutaneous needle biopsy using a University College Hospital needle under local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine.36 Visible blood and connective tissue were removed from muscle specimens, and portions for mitochondrial analyses were immediately analyzed by respirometry.

High-Resolution Respirometry of Permeabilized Skeletal Muscle Fibers

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation can be evaluated by measuring the rate of oxygen consumption in cells and tissues.37,38,39 High-resolution respirometry of permeabilized skeletal muscle fiber bundles was performed following a protocol in which substrates and inhibitors are sequentially added to measure oxygen flux mediated by mitochondrial complexes I and II respiration, as well as maximal uncoupled respiration maximal capacity. Together, these primary outcomes (complex I respiration, complexes I and II respiration, and maximal capacity) report on the maximal bioenergetic capacity of the electron transport system and the contributions of the 2 major electron transport chain entry points to this capacity. Following previously published protocols,40 approximately 2.5 mg (wet weight) of tissue were loaded into each of 2 chambers of an Oroboros Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros), and steady-state rate of respiration measurements were obtained after every substrate addition and expressed as picomoles per second per milligram of tissue.41 High-resolution oxygen flux measurements were measured in 2-mL buffer Z containing 20mM of creatine and 25μM of blebbistatin to inhibit contraction.41 This injection protocol was completed as follows: 2mM of malate, 4mM of adenosine diphosphate, 20mM of pyruvate, 10mM of glutamate (complex I substrates), 10mM of succinate (complex II substrates), 10μM of cytochrome c to test for mitochondrial membrane integrity, 2 additions of 0.25μM of carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoro methoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) followed by a titration of 0.5μM of FCCP to obtain maximal electron transfer capacity, 0.5μM of rotenone, and 5μM of antimycin A. Each sample was run in duplicate, and all data were normalized to measured muscle fiber bundle wet weight. All assays were performed under a high initial oxygen concentration (350uM to 400uM) in the O2K chamber (Oroboros Instruments).

Statistical Analysis

Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to check for normal distribution of all variables. Log transformations were performed for parameters with nonnormal distribution. Intergroup (HFpEF vs HC) comparisons of participant characteristics were made by independent-samples t tests and χ2 tests. Intergroup differences in bioenergetics parameters were compared using independent-samples t tests; additionally, to account for the differences in sex, BMI, and age, adjustments for these variables were made using analysis of covariance. Intergroup in-exercise and physical function measures were assessed using independent-samples t tests as well as adjustment for sex using analysis of covariance. Pearson correlation coefficients were assessed between all variables, both raw and normalized values, and partial correlations adjusted for age, sex, and BMI were also assessed. Significance between groups was defined as P < .05, and all P values were 2-tailed. Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 26 (IBM).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of 72 included patients, 50 (69%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 69.6 (6.1) years. A total of 27 patients with HFpEF and 45 age-matched HCs were included. Patients with HFpEF had characteristics typical of population-based studies of chronic, stable HFpEF with New York Heart Association class II to III symptoms with increased left ventricular mass and abnormal Doppler left ventricular diastolic function compared with HCs and with typical comorbidities (27 [100%] with hypertension and 10 [37%] with diabetes), and 25 [93%] were taking diuretics (Table 1). Patients with HFpEF and HCs were well matched for age; however, there were more women in the HFpEF group. Body mass, fat mass, percentage body fat, and BMI were higher in those with HFpEF compared with HCs, in accord with observations in multiple population-based studies and trials that have reported significantly higher BMI in patients with HFpEF compared with the general population.42,43,44,45,46

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) and Age-Matched Healthy Controls (HCs).

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with HFpEF (n = 27) | HCs (n = 45) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.4 (5.8) | 70.2 (6.2) | .22 |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 4 (15) | 9 (20) | .39 |

| Women | 23 (85) | 36 (80) | |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 163.8 (8.3) | 165.8 (9.7) | .38 |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 104.9 (20) | 74.1 (14.3) | <.001 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)a | 38.9 (6.2) | 26.8 (3.7) | <.001 |

| Body surface area, mean (SD), m2 | 2.08 (0.22) | 1.82 (0.21) | <.001 |

| Total fat mass, mean (SD), kg | 51.8 (12.3) | 29.6 (7.7) | <.001 |

| Total lean mass, mean (SD), kg | 54.4 (10.1) | 43.4 (9.7) | <.001 |

| Body fat, mean (SD), % | 49 (5) | 39 (7) | <.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 144.9 (20.5) | 121.6 (11) | <.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 75 (11) | 69 (9) | .01 |

| Ejection fraction, mean (SD), % | 61 (4) | 59 (4) | .45 |

| Left ventricular mass, mean (SD), g | 205.4 (45.8) | 156.8 (33.8) | <.001 |

| Left ventricular mass index, mean (SD) | 98.3 (18.8) | 83.8 (4.4) | .02 |

| Left atrial diameter, mean (SD), cm | 3.9 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.5) | .12 |

| E/A ratio, mean (SD) | 0.97 (0.32) | 0.86 (0.23) | .21 |

| e′ septal, mean (SD), cm/s | 6.4 (1.9) | 7.8 (1.5) | .02 |

| E/e′ ratio, mean (SD) | 13.3 (6.4) | 9.4 (2.8)b | .031 |

| N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide, median (IQR), pg/mL | 86 (82-145)c | NA | NA |

| Diastolic filling pattern | |||

| Normal | 1 (4) | 3 (20) | .03 |

| Impaired | 24 (89) | 8 (53) | |

| Pseudonormal | 2 (7) | 4 (27) | |

| Restrictive | 0 | 0 | |

| History of hypertension | 27 (100) | NA | NA |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 2 (7) | NA | NA |

| History of coronary heart disease | 5 (19) | NA | NA |

| Diabetes | 10 (37) | NA | NA |

| New York Heart Association HF class | |||

| I | 1 (4) | NA | NA |

| II | 8 (31) | NA | NA |

| III | 12 (46) | NA | NA |

| IV | 5 (19) | NA | NA |

| Medications | |||

| Diuretics | 25 (93) | NA | NA |

| Angiotensin-II receptor blockers | 11 (41) | NA | NA |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 10 (37) | NA | NA |

| β-Blockers | 12 (44) | NA | NA |

| Calcium channel blockers | 6 (22) | NA | NA |

| Nitrates | 1 (4) | NA | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Measured in only 15 HCs.

Values derived from the parent clinical trial.28

Exercise Performance

Patients with HFpEF had severely reduced peak VO2 compared with HCs (Table 2).9,47 This was evident despite similar peak exercise respiratory exchange ratio in HFpEF vs HC, which was 1.08 or more in both groups, indicating exhaustive exercise effort. There was nonsignificantly lower peak heart rate in patients with HFpEF vs HC. Six-minute walk distance was also significantly reduced in HFpEF compared with HC. Both SPPB chair stand and walk (4 m) times were higher in patients with HFpEF compared with HC, resulting in overall lower SPPB scores in patients with HFpEF. Left leg strength was significantly reduced in patients with HFpEF compared with HCs.

Table 2. Cardiopulmonary and Hemodynamic Responses During Peak Treadmill Exercise and Physical Function Measures.

| Measure | Raw data, mean (SD) | Adjusted data, mean (SE)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with HFpEF | HCs | P value | Patients with HFpEF | HCs | P value | |

| Peak VO2, mL/kg/min | 14.8 (3.0) | 26.0 (6.6) | <.001 | 15.0 (1.0) | 25.9 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Peak VO2, mL/min | 1539 (393) | 1923 (643) | .007 | 1569 (84) | 1905 (65) | .002 |

| Peak VCO2, mL/min | 1665 (433) | 2162 (832) | .005 | 1703 (105) | 2139 (82) | .002 |

| Ventilatory anaerobic threshold, mL/min | 1111 (271) | 1001 (367) | .91 | 1022 (57) | 988 (44) | .64 |

| Peak respiratory exchange ratio | 1.08 (0.07) | 1.11 (0.10) | .17 | 1.08 (0.02) | 1.11 (0.01) | .21 |

| Peak heart rate, beats per min | 138 (22) | 152 (16) | .002 | 138 (4) | 152 (3) | .003 |

| Peak systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 190 (22) | 176 (17) | .003 | 190 (4) | 176 (3) | .002 |

| Peak diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 81 (10) | 79 (11) | .68 | 81 (2) | 79 (1) | .50 |

| 6-min Walk distance, m | 373 (61) | 546 (94) | <.001 | 375 (16) | 545 (12) | <.001 |

| SPPB 4-m walk time, s | 5.1 (1.0) | 3.7 (0.9) | <.001 | 5.1 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.1) | <.001 |

| SPPB chair time, s | 14.1 (4.0) | 9.6 (2.0) | <.001 | 14.1 (0.6) | 9.6 (0.4) | <.001 |

| SPPB total score, units | 9.9 (1.6) | 11.6 (1.1) | <.001 | 9.9 (0.2) | 11.6 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Right leg strength, N · m | 87.0 (27.2) | 101.5 (37.3) | .14 | 87.9 (7.2) | 100.6 (5.0) | .15 |

| Left leg strength, N · m | 79.9 (21.3) | 107.7 (35.2) | .006 | 81.9 (7.1) | 105.6 (4.4) | .007 |

Abbreviations: HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HC, healthy control; peak VCO2, peak carbon dioxide output; peak VO2, peak exercise oxygen consumption; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Adjusted for sex.

Skeletal Muscle Bioenergetic Characteristics

A representative trace depicting the high-resolution respirometry protocol used for this project is shown in eFigure 1 in Supplement 1. Comparisons of bioenergetic measures between patients with HFpEF and HCs are shown in Table 3. Across complex I respiration, complexes I and II respiration, and maximal capacity, the mean oxygen consumption rates per mg muscle were significantly reduced in patients with HFpEF compared with HCs. When the data were adjusted for sex, age, and BMI, individually and together, differences remained statistically significant.

Table 3. Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Respirometry.

| Parameter | Oxygen consumption rate, mean (SE), pmol/s−1/mg muscle | P valuea | P valueb | P valuec | P valued | P valuee | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with HFpEF (n = 27) | HCs (n = 45) | ||||||

| Complex I respiration | 10.7 (3.8) | 28.2 (8.0) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Complexes I and II respiration | 15.9 (5.4) | 40.1 (11.8) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Maximal capacity | 24.4 (9.4) | 61.4 (13.7) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HC, healthy control.

Unadjusted.

Adjusted for sex.

Adjusted for age.

Adjusted for body mass index.

Adjusted for sex, age, and body mass index.

Correlations Between Skeletal Muscle Bioenergetics and Measures of Physical Function

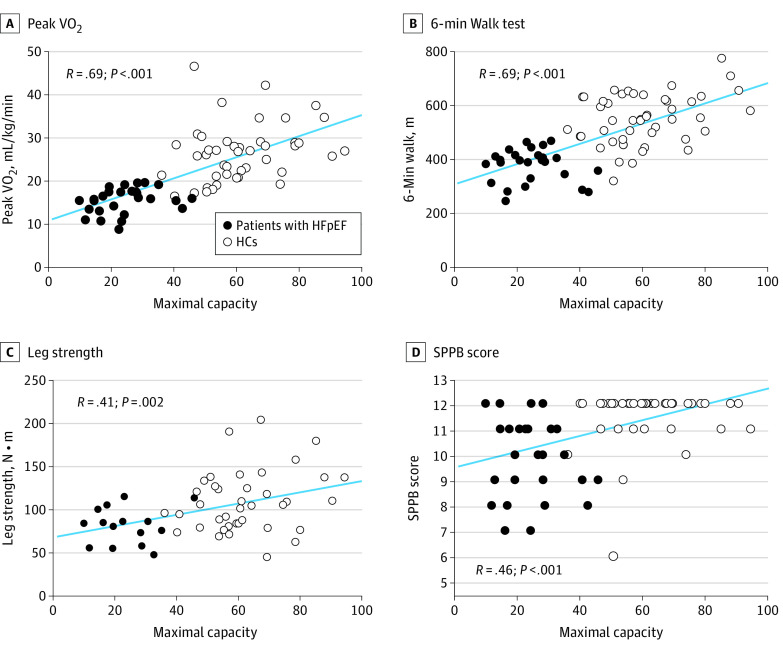

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine correlations between skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and measures of physical function across participants with HFpEF and HCs. The results are summarized in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Both absolute and relative peak VO2 (per kg weight) were significantly positively correlated with complex I respiration (R = 0.70; P < .001), complexes I and II respiration (R = 0.69; P < .001), and maximal capacity (R = 0.69; P < .001) (Figure, A). Similarly, 6-minute walk distance (R = 0.69; P < .001) and leg strength (R = 0.41; P < .001) had positive correlations with skeletal muscle respiration (Figure, B and C). SPPB scores were positively correlated with skeletal muscle fiber respiration (R = 0.46; P < .001), while its individual components, gait time and chair stands, showed negative correlations (Figure, D; eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess whether the correlation between skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and peak VO2 differed between the patients with HFpEF and HCs using both stratified correlation analysis (eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 1) and regression analysis with an interaction term. Results of the sensitivity analyses indicate similar correlations between patients with HFpEF (R = 0.28; P = .15) and HCs (R = 0.28; P = .06) for peak VO2 and maximal capacity, respectively, and all tests for interaction were nonsignificant.

Figure. Associations of Maximal Capacity With Exercise Capacity and Physical Ability.

The blue line indicates the simple linear regression line. HC indicates healthy control; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; peak VO2, peak exercise oxygen consumption; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Discussion

This study using respirometry of skeletal muscle fiber bundles obtained from biopsy in patients with HFpEF compared with age-matched HCs, to our knowledge, provides the first direct evidence indicating that cellular-level mitochondrial dysfunction underlies skeletal muscle metabolic abnormalities in those with HFpEF and is associated with multiple objective measures of severe exercise intolerance, including reduced peak VO2, 6-minute walk distance, SPPB, and leg strength. These mitochondrial abnormalities represent potential therapeutic targets, as the function of these organelles is linked to many common disease processes and potentially modifiable by both pharmacological interventions as well as behavioral interventions, such as diet and exercise.48

Patients with chronic HFpEF have severe exercise intolerance that is associated with impaired quality of life.7,9,15 To date, the mechanistic underpinnings of HFpEF exercise intolerance remain incompletely understood, thus hampering efforts to develop effective interventions. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that in addition to cardiac factors, noncardiac peripheral factors, including abnormal skeletal muscle metabolism, contribute to the severe exercise intolerance in patients with HFpEF.9,12,15,49,50,51,52 We have previously reported that mitochondrial content and oxidative capacity are significantly reduced in skeletal muscle biopsy samples from patients with HFpEF.19 Furthermore, we reported that expression of Mfn2, a key mediator of mitochondrial fusion, is similarly decreased. Notably, these mitochondrial impairments were associated with measures of exercise intolerance, specifically peak VO2 and 6-minute walk distance. However, these previous studies examining mitochondria in patients with HFpEF were limited due to the reliance on stored frozen tissues samples, which prevented analyses of mitochondrial function by respirometry, a direct and precise approach for assessing mitochondrial function.

In this study, we used high-resolution respirometric profiling of permeabilized skeletal muscle fiber bundles to provide, to our knowledge, the first direct analysis of mitochondrial function in patients with HFpEF. The major new finding is that compared with age-matched HCs, patients with HFpEF had lower mitochondrial respiration across measures of oxidative phosphorylation capacity of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide plus hydrogen (NADH) pathway through complex I respiration, convergent NADH and succinate (NS) pathways through complexes I and II respiration, and electron transfer capacity of the convergent NS pathway. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that excess adipose tissue is associated with impaired mitochondrial function and reduced mitochondrial density.53,54 Given that more than 80% of patients with HFpEF are overweight or obese, twice the rate found in the general older population,44,45 we analyzed whether this difference could contribute to impaired skeletal muscle function. Adjusting for BMI did not affect the differences in mitochondrial respiration we observed between participants with HFpEF and HCs. Thus, our results indicate that factors unrelated to obesity also contribute to skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with HFpEF. This is consistent with findings from an animal model of HFpEF, which showed reduced skeletal muscle mitochondrial density compared with controls, despite no difference in body mass.20 Similarly, adjusting for age did not account for differences in mitochondrial respiration.

Among healthy persons, skeletal muscle mitochondrial function has been shown to be directly related to physical function and exercise capacity, supporting our observation that mitochondrial abnormalities in patients with HFpEF are associated with their severely impaired physical function.55,56 Coen et al57 reported that the respiratory capacity of muscle fibers and maximal phosphorylation capacity are associated with peak VO2 and walk speed in older adults. Notably, the average peak VO2 in that study was 22.0 mL·min−1·kg−1, while the average peak VO2 in our HFpEF cohort was 14.8 mL·min−1·kg−1, in line with differences associated with disease.

Mitochondrial abnormalities are emerging as promising therapeutic targets for a number of common disorders, particularly those associated with aging, such as HFpEF.48 Notably, mitochondrial function is modifiable and responsive to interventions. The present data provide the foundation for future studies to examine interventions, such as exercise training, which has been shown to positively affect skeletal muscle mitochondria function.58,59 The present data suggest the possibility that alterations in mitochondrial function may underlie our previous observation that the increase in arteriovenous oxygen difference, which accounts for 90% of the increase in peak VO2 in patients with HFpEF following exercise training, is primarily due to noncardiac factors, particularly skeletal muscle function,14,15,60 since arterial stiffness and conduit arterial endothelial dysfunction do not appear to improve with exercise training in HFpEF.51 This concept should be confirmed in future exercise intervention studies using bioenergetic profiling strategies similar to those used in the present study. Pharmacological interventions targeting mitochondrial abnormalities are also in development. For example, Szeto-Schiller peptides have been shown to target mitochondrial dysfunction in myocytes and are being tested in clinical trials.61 Additional potentially therapeutic molecules targeting mitochondria include coenzyme Q10, MitoQ, mitochondrial division inhibitor 1, and nicotinamide mononucleotide.48 Notably, previous clinical trials have been focused on effects on cardiac function in patients with HFpEF. The present data suggest that clinical trials targeting mitochondrial abnormalities in HFpEF may have beneficial effects on skeletal muscle metabolism and exercise performance.

Strengths and Limitations

A primary strength of this article is the use of high-resolution respirometry to directly assess mitochondrial function in freshly isolated permeabilized skeletal muscle fiber bundles. These precise ex vivo measurements have significantly advanced our understanding of human muscle metabolism. To our knowledge, the study presented here is the largest to use these assays in patients with HFpEF. Other strengths include an age-matched HC group and the multiple measures of physical function and exercise capacity, including peak VO2, 6-minute walk distance, SPPB, and leg strength, to determine their association with the mitochondrial abnormalities.

This study has limitations. Patients with HFpEF compared with HC participants were well matched for age and sex distribution but had higher BMI. While this reflects the nature of HFpEF, since more than 80% of patients with HFpEF are overweight or obese, twice the rate of the general population, it creates uncertainty regarding independent effects, since excess adiposity may affect skeletal muscle mitochondria53,59,62; hence, the potential associations of obesity with skeletal muscle mitochondria should be considered in the interpretation of these results. However, we included models adjusting for BMI individually and in conjunction with age and sex in our analyses and found that differences between participants with HFpEF and HCs were largely unaffected. Another potential difference that could affect our readouts of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function is the relative abundance of type 1 muscle fibers, which have a distinct metabolic phenotype. Our team has previously reported that the relative abundance of type 1 fibers is lower in the skeletal muscle of participants with HFpEF18; however, comparative data reporting on the abundance of type 1 fibers are not available in this study.

Several studies in both animal models and humans have reported that physical activity and sedentary behavior are related to skeletal muscle mitochondrial function.63,64 A limitation of this work is that differences in physical activity and sedentary behavior, which have been reported in patients with HFpEF,65,66 were not measured in this study. While we cannot definitely decipher whether skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction is a cause or consequence of differences in physical activity in HFpEF compared with HCs, it should be noted that reduced physical function (such as pVO2) in HFpEF is not merely due to sedentary behavior. This concept is supported by multiple lines of evidence for skeletal myopathy in HFpEF, as previously reviewed by our team.60 Similarly, the data presented in this article serve to highlight the presence of severe skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with HFpEF and reports on the correlations of these measures with multiple measures of physical ability and fitness. However, the causal relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and exercise intolerance in patients with HFpEF remains to be determined.

Conclusions

In this study, older patients with HFpEF showed marked abnormalities in mitochondrial function that were significantly associated with their reduced exercise capacity and muscle strength. These results provide new insights into potential novel therapeutic targets.

eTable 1. Correlation Between Skeletal Muscle Respiration and Physical Function

eTable 2. Correlation Between Skeletal Muscle Respiration and Peak VO2 by HFpEF Status

eFigure 1. Representative High-Resolution Respirometry Trace

eFigure 2. Association Between Skeletal Muscle Respiration and Peak VO2 in HFpEF and Healthy Controls

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):251-259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Gottdiener JS, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group . Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients ≥65 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(4):413-419. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01393-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunlay SM, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(10):591-602. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieske B, Tschöpe C, de Boer RA, et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(3):391-412. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Riet EE, Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Limburg A, Landman MA, Rutten FH. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. a systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(3):242-252. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seferović PM, Petrie MC, Filippatos GS, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(5):853-872. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, et al. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2144-2150. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Russell SD, et al. Impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2006;114(20):2138-2147. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, John JM, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Determinants of exercise intolerance in elderly heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):265-274. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito F, Mathieu-Costello O, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Limited maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: partitioning the contributors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(18):1945-1954. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan MJ, Knight JD, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR. Relation between central and peripheral hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. muscle blood flow is reduced with maintenance of arterial perfusion pressure. Circulation. 1989;80(4):769-781. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.80.4.769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey A, Shah SJ, Butler J, et al. Exercise intolerance in older adults with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(11):1166-1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhakal BP, Malhotra R, Murphy RM, et al. Mechanisms of exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the role of abnormal peripheral oxygen extraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(2):286-294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleg JL, Cooper LS, Borlaug BA, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group . Exercise training as therapy for heart failure: current status and future directions. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(1):209-220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(2):120-128. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Kritchevsky S, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Impaired aerobic capacity and physical functional performance in older heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: role of lean body mass. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(8):968-975. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss K, Schär M, Panjrath GS, et al. Fatigability, exercise intolerance, and abnormal skeletal muscle energetics in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(7):10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitzman DW, Nicklas B, Kraus WE, et al. Skeletal muscle abnormalities and exercise intolerance in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306(9):H1364-H1370. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00004.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina AJ, Bharadwaj MS, Van Horn C, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial content, oxidative capacity, and Mfn2 expression are reduced in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction and are related to exercise intolerance. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4(8):636-645. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowen TS, Rolim NP, Fischer T, et al. ; Optimex Study Group . Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction induces molecular, mitochondrial, histological, and functional alterations in rat respiratory and limb skeletal muscle. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(3):263-272. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley RC, Betancourt L, Noriega AM, et al. Skeletal myopathy in a rat model of postmenopausal heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2022;132(1):106-125. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00170.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haykowsky MJ, Herrington DM, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Hundley WG, Kitzman DW. Relationship of flow-mediated arterial dilation and exercise capacity in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(2):161-167. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(6):659-667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott JM, Haykowsky MJ, Eggebeen J, Morgan TM, Brubaker PH, Kitzman DW. Reliability of peak exercise testing in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(12):1809-1813. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147-e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1190-1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schocken DD, Arrieta MI, Leaverton PE, Ross EA. Prevalence and mortality rate of congestive heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20(2):301-306. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90094-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brubaker PH, Nicklas BJ, Houston DK, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of resistance training added to caloric restriction plus aerobic exercise training in obese heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2023;16(2):e010161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.122.010161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stehle JR Jr, Leng X, Kitzman DW, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB, High KP. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, a surrogate marker of microbial translocation, is associated with physical function in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1212-1218. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitzman DW, Brubaker P, Morgan T, et al. Effect of caloric restriction or aerobic exercise training on peak oxygen consumption and quality of life in obese older patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(1):36-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, et al. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. CMAJ. 1985;132(8):919-923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt MC, et al. ; Health ABC Study Group . Measuring higher level physical function in well-functioning older adults: expanding familiar approaches in the Health ABC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(10):M644-M649. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.M644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitzman DW, Whellan DJ, Duncan P, et al. Physical rehabilitation for older patients hospitalized for heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(3):203-216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bharadwaj MS, Tyrrell DJ, Lyles MF, Demons JL, Rogers GW, Molina AJ. Preparation and respirometric assessment of mitochondria isolated from skeletal muscle tissue obtained by percutaneous needle biopsy. J Vis Exp. 2015;7(96):52350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyrrell DJ, Bharadwaj MS, Van Horn CG, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Molina AJ. Respirometric profiling of muscle mitochondria and blood cells are associated with differences in gait speed among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1394-1399. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicklas BJ, Leng I, Delbono O, et al. Relationship of physical function to vastus lateralis capillary density and metabolic enzyme activity in elderly men and women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20(4):302-309. doi: 10.1007/BF03324860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu M, Neilson A, Swift AL, et al. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292(1):C125-C136. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maruszak A, Żekanowski C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(2):320-330. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onyango IG, Dennis J, Khan SM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and the rationale for bioenergetics based therapies. Aging Dis. 2016;7(2):201-214. doi: 10.14336/AD.2015.1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doerrier C, Garcia-Souza LF, Krumschnabel G, Wohlfarter Y, Mészáros AT, Gnaiger E. High-Resolution FluoRespirometry and OXPHOS protocols for human cells, permeabilized fibers from small biopsies of muscle, and isolated mitochondria. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1782:31-70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7831-1_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perry CG, Kane DA, Lin CT, et al. Inhibiting myosin-ATPase reveals a dynamic range of mitochondrial respiratory control in skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 2011;437(2):215-222. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah AM, Solomon SD. Phenotypic and pathophysiological heterogeneity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(14):1716-1717. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, et al. Cardiac structure and function and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the echocardiographic study of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(5):740-751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, et al. ; RELAX Trial . Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(12):1268-1277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haass M, Kitzman DW, Anand IS, et al. Body mass index and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (I-PRESERVE) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):324-331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anjan VY, Loftus TM, Burke MA, et al. Prevalence, clinical phenotype, and outcomes associated with normal B-type natriuretic peptide levels in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(6):870-876. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haykowsky MJ, Kouba EJ, Brubaker PH, Nicklas BJ, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Skeletal muscle composition and its relation to exercise intolerance in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(7):1211-1216. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy MP, Hartley RC. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for common pathologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(12):865-886. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhella PS, Prasad A, Heinicke K, et al. Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(12):1296-1304. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, et al. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(11):845-854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Herrington DM, et al. Effect of endurance exercise training on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(7):584-592. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puntawangkoon C, Kitzman DW, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Reduced peripheral arterial blood flow with preserved cardiac output during submaximal bicycle exercise in elderly heart failure. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bharadwaj MS, Tyrrell DJ, Leng I, et al. Relationships between mitochondrial content and bioenergetics with obesity, body composition and fat distribution in healthy older adults. BMC Obes. 2015;2:40. doi: 10.1186/s40608-015-0070-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, et al. ; CALERIE Pennington Team . Calorie restriction increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4(3):e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez-Freire M, Scalzo P, D’Agostino J, et al. Skeletal muscle ex vivo mitochondrial respiration parallels decline in vivo oxidative capacity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscle strength: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Aging Cell. 2018;17(2):17. doi: 10.1111/acel.12725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coen PM, Menshikova EV, Distefano G, et al. Exercise and weight loss improve muscle mitochondrial respiration, lipid partitioning, and insulin sensitivity after gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes. 2015;64(11):3737-3750. doi: 10.2337/db15-0809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coen PM, Jubrias SA, Distefano G, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics are associated with maximal aerobic capacity and walking speed in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(4):447-455. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Porter C, Reidy PT, Bhattarai N, Sidossis LS, Rasmussen BB. Resistance exercise training alters mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(9):1922-1931. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toledo FG, Goodpaster BH. The role of weight loss and exercise in correcting skeletal muscle mitochondrial abnormalities in obesity, diabetes and aging. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;379(1-2):30-34. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitzman DW, Haykowsky MJ, Tomczak CR. Making the case for skeletal muscle myopathy and its contribution to exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(7):10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Daubert MA, Yow E, Dunn G, et al. Novel mitochondria-targeting peptide in heart failure treatment: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of elamipretide. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(12):10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Menshikova EV, Ritov VB, Toledo FG, Ferrell RE, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE. Effects of weight loss and physical activity on skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(4):E818-E825. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00322.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Powers SK, Wiggs MP, Duarte JA, Zergeroglu AM, Demirel HA. Mitochondrial signaling contributes to disuse muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(1):E31-E39. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00609.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Distefano G, Standley RA, Zhang X, et al. Physical activity unveils the relationship between mitochondrial energetics, muscle quality, and physical function in older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(2):279-294. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rariden BS, Boltz AJ, Brawner CA, et al. Sedentary time and cumulative risk of preserved and reduced ejection fraction heart failure: from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Card Fail. 2019;25(6):418-424. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pandey A, Berry JD. Physical activity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: moving toward a newer treatment paradigm. Circulation. 2017;136(11):993-995. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Correlation Between Skeletal Muscle Respiration and Physical Function

eTable 2. Correlation Between Skeletal Muscle Respiration and Peak VO2 by HFpEF Status

eFigure 1. Representative High-Resolution Respirometry Trace

eFigure 2. Association Between Skeletal Muscle Respiration and Peak VO2 in HFpEF and Healthy Controls

Data Sharing Statement