Abstract

Epidemiological data regarding the incidence of secondary multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative infection in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Brazil are still ambiguous. Thus, a case-control study was designed to determine factors associated with the acquisition of MDR Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) in patients with and without COVID-19 and describe the mortality rates and clinical features associated with unfavorable outcomes. In total, we assessed 280 patients admitted to Brazilian intensive care units from March/2020 to December/2021. During the study, 926 GNB were isolated. Out of those, 504 were MDR-GNB, representing 54.4% of the resistance rate. In addition, out of 871 patients positive for COVID-19, 73 had secondary MDR-GNB infection, which represented 8.38% of documented community-acquired GNB-MDR infections. The factors associated with patients COVID-19-MDR-GNB infections were obesity, heart failure, use of mechanical ventilation, urinary catheter, and previous use of β-lactams. Several factors associated with mortality were identified among patients with COVID-19 infected with MDR-GNB, including the use of a urinary catheter; renal failure; and the origin of bacterial cultures such as tracheal secretion, exposure to carbapenem antibiotics, and polymyxin. Mortality was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB (68.6%) compared to control groups, where COVID-19 was 35.7%, MDR-GNB was 50%, and GNB was 21.4%. Our findings demonstrate that MDR-GNB infection associated with COVID-19 has an expressive impact on increasing the case fatality rate, reinforcing the importance of minimizing the use of invasive devices and prior exposure to antimicrobials to control the bacterial spread in healthcare environments to improve the prognosis among critical patients.

Keywords: Healthcare-associated infections, Antimicrobial resistance, Public health, SARS-CoV-2, Multi-drug resistance

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an emerging global public health challenge hampering the health of mainly critically ill patients [1], [2]. An estimated annual 4.95 million deaths are associated with bacterial resistance, with projections suggesting that by 2050, approximately 10 million individuals could die each year due to the ineffectiveness of controlling and combating AMR [3], [4]. Additionally, long hospitalization, previous use of antimicrobials, and invasive and surgical procedures are some factors associated with the occurrence of AMR [5], [6].

The emergence and spread of resistant microorganisms is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by several interrelated and interdependent factors [7]. These vary in different regions and include the excessive and inappropriate use of antimicrobial agents, inadequate infection control measures, migration of people, and the lack of development of new and effective antimicrobial agents [8]. However, these factors were further exacerbated by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). The increased hospitalization rates and admission in intensive care units (ICUs), inappropriate or overuse of antibiotics in many patients, and growing global antibiotic use were observed. The long-term consequences of the pandemic are still unknown. However, there is a particular concern, especially with regard to the spread of resistance and underlying patient risk factors [9], [10], [11].

MDR-GNB are resistant pathogens of the highest priority according to the World Health Organization (WHO) due to their dissemination in the hospital environment, causing a variety of infections associated with increased morbidity and mortality [9], [12]. Surveillance of patients with MDR-GNB is essential in healthcare environments to improve patient prognosis [5], especially in critically ill patients with COVID-19, where secondary infections were identified in 50% of deaths [11]. Therefore, identifying predictive factors related to the occurrence of MDR-GNB infections can contribute to containing and preventing their spread, particularly those with COVID-19, and reducing unfavorable outcomes [13], [14].

Nevertheless, investigations on the prediction factors associated with MDR-GNB infections in COVID-19 patients remains limited [13], [15]. Therefore, the present case-control study aimed to investigate the factors associated with the occurrence of MDR-GNB in adults with and without COVID-19 admitted to Brazilian ICUs, and to describe the mortality rates and clinical characteristics of these infections.

Material and methods

Study site and patients

The data were collected from patients hospitalized in a public tertiary care hospital in Dourados, Brazil, between March 2020 and December 2021. This hospital has 237 beds, including infirmaries and the ICUs (adult, pediatric, and neonatal), with an average of 9800 annual admissions. Patients with MDR-GNB isolated from clinical cultures from any source, such as tracheal aspirates, catheter tips, swabs (rectal), and blood and urine cultures, were included in this study. The microbiological samples were cultured followed recommendations of laboratory procedures and methods for different types of samples, including respiratory [16]. Tracheal aspirate, urine, and catheter samples were cultured quantitatively, with a positivity cutoff set at 1000,000 CFU/mL. Semi-quantitative culture techniques were used for blood culture, biopsy, and bronchoalveolar lavage [16].

Patients under 18 years with incomplete records, those transferred to other hospitals before discharge from the ICU, or those who were not monitored for loss of data or incorrect records were excluded. The records of the same patient with different clinical sources of infection were also excluded, and only the first record was considered.

Definitions

MDR was defined as resistance to one or more antimicrobials from three or more tested categories [17]. Nosocomial infection was defined by the clinical diagnosis based on the clinical criteria (sepsis, fever, changes in the frequency or color of secretions, or new radiological findings), initiated> 48 h after hospital admission or within 48 h after hospital discharge, associated with the occurrence of a multidrug-resistant microorganism [18]. In contrast, other infections were considered community-acquired [15]. COVID-19 was defined as a positive real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a nasopharyngeal swab associated with suggestive clinical signs, symptoms, and/or radiological findings. The time from COVID-19 detection and initial presentation to culture time was used to assess likely community (<120 h from admission) or healthcare-associated infection (>120 h from admission). This time point was agreed upon by the study team to define the pathogens associated with health in this study [19].

Study design

A case-control study was performed to identify factors associated with the occurrence of MDR-GNB in patients with or without COVID-19. A case (COVID-19-MDR-GNB) was defined as a patient positive for COVID-19 from whom an MDR-GNB was isolated from clinical cultures from any source during the study. Control 1 was defined as patients positive for COVID-19 admitted in the same study period. Control 2 included patients admitted in the same study period from whom an MDR-GNB was isolated from a clinical culture at least 48 h after admission and no clinical or microbiological evidence of COVID-19. Control 3 included patients admitted in the same study period from whom a susceptible GNB was isolated from a clinical culture at least 48 h after admission and there was no clinical or microbiological evidence of COVID-19. Non-probabilistic controls, randomly recruited in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to cases. Case and controls were matched for age, clinical manifestations, pathogens, and hospital wards. The inclusion of a case or control was only possible once. A two-part analysis was performed as follows: i) a case-control study in which cases were compared with controls to identify potential factors associated with the isolation of MDR-GNB in adult ICU, and ii) a retrospective analysis to measure mortality associated with the isolation of MDR-GNB.

Clinical data

The clinical, nursing, and microbiological records of hospitalized patients were reviewed retrospectively. The following data were recorded: demographics; medical history; comorbidities; location before admission; ward of admission; hospital course (duration and ward location); invasive procedures; surgery; use of invasive medical devices (mechanical ventilation, total parenteral nutrition, urinary catheter, drainage tube, nasogastric tube, tracheal intubation); treatment with immunosuppressive drugs; and source of infection (blood, urinary tract, wound, respiratory source or other). All antibiotics administered for ≥ 24 h during the current hospitalization were recorded. The information collected included the drug name, start date, dose, route of administration, dosing frequency, and total duration of use. Data regarding the clinical outcome (recovery/death) were reviewed, and death owing to any cause or death attributable to infection was assessed.

Bacterial identification and susceptibility testing

The bacterial species identification and screening for antimicrobial resistance were performed using Phoenix® Automated System (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This method used biochemical parameters for bacterial identification, employing conventional, fluorogenic, and modified chromogenic substrates. Antimicrobial panels for susceptibility testing were also assessed. The system software automatically interprets the results [20], [21].

Statistical analysis

The Research Electronic Data Capture (Redcap) was used for the database, and statistical analysis was performed by SAS v.19.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using univariate and multivariate models. Dichotomized and categorical data were analyzed using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. For continuous variables, a t-test or analysis of variance was used. Univariate analyses were performed to verify associations between the dependent and independent variables, and those achieving a prespecified level of significance (P < 0.2) were included in the multivariable analysis. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. To evaluate the strength of associations, a logistic regression analysis was used to estimate crude, adjusted odds ratios (OR), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Additionally, we performed Kaplan-Meier plot analysis to visualize survival curves, cox regression, and log-rank test to compare survival curves.

Results

Patient characteristics

According to routine microbiological analysis carried out at the hospital between 2020 and 2021, a total of 926 GNB were identified. Among these, 422 isolates were susceptible to antibiotics and, 504 were MDR-GNB, representing a high resistance rate of 54.4%. Additionally, 145 patients carrying MDR-GNB strains were included in this study. Out of those, 70 patients were included to compose the MDR-GNB control group ( Fig. 1). Furthermore, in the MDR-GNB control group, 62 strains were identified as community-acquired.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the process of defining and selecting cases and controls. Abbreviations: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); COVID-19, coronavirus 19; MDR, multidrug resistant; Gram-negative bacteria (GNB).

In total, 280 adult patients (compared data from the 70 cases with 210 controls) were included, the median age was 56 years (range 18–92 years), and the majority were women (n = 143; 51%) with 22.07 days (range 1–102 days) of mean length of hospital stay. In the sample studied, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) between cases and controls with respect to baseline demographics.

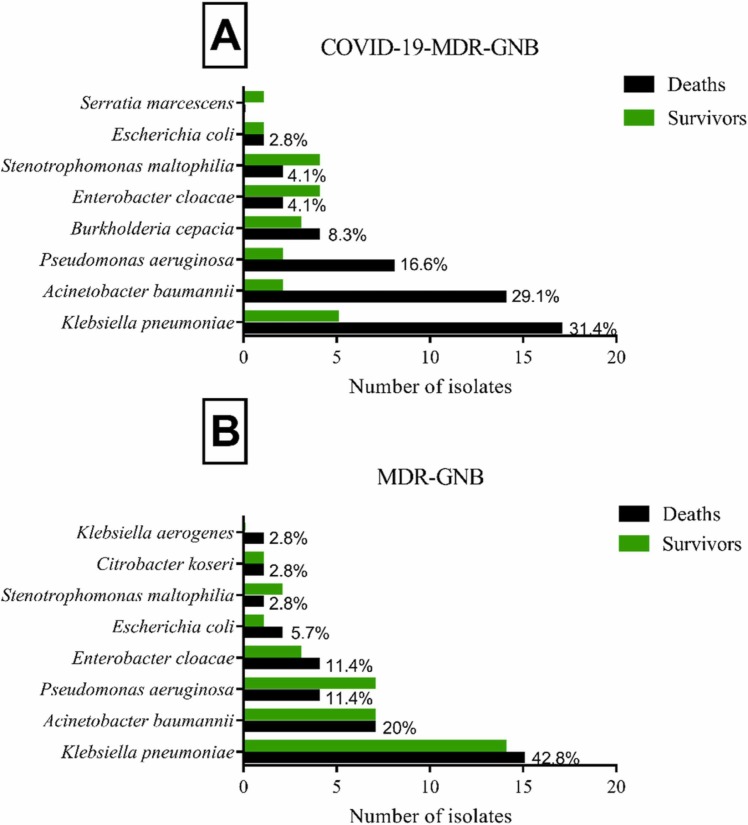

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii are the main MDR-GNB species (68%) isolated in the present hospital during the period studied. For diagnosing COVID-19, 1953 patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital, and 871 had a positive test. Among these, 73 patients had secondary infections with MDR-GNB, which represents a rate of 8.38%. Among these, 70 patients were included to compose the COVID-19-MDR-GNB case group; 22 strains were identified as nosocomial and 48 strains as community-acquired. In patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB and MDR-GNB, the most prevalent microorganism identified was K. pneumoniae, representing 31.4% and 41.4%, respectively ( Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total number of MDR-GNB species isolated from study patients: A) COVID-19-MDR-GNB case group (n = 70); B) MDR-GNB control group (n = 70).

Factors associated with MDR-GNB

Case patients (COVID-19-MDR-GNB) were compared to the control group (COVID-19), aiming to analyze the factors associated with the occurrence of MDR-GNB in hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis. Renal failure, use of mechanical ventilation, central venous catheter, nasoenteral tube, and length of stay up to 30 days were identified as factors associated with the acquisition of MDR-GNB among patients with COVID-19 in a univariate analysis.

Among COVID-19-MDR-GNB, the majority of patients were men; and use of antimicrobials (β-lactams, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, cephalosporins, quinolones, and polymyxins) was associated with the occurrence of MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19. Multivariate analysis revealed that renal failure, hospital stay longer than 30 days, and use of carbapenems and β-lactams were all independently associated with MDR-GNB isolation. Additionally, the outcome of death was independently associated with an increased risk of death by 3.29 in patients with MDR-GNB ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate and multi-variate analysis between COVID-19-MDR-GNB patients compared to COVID-19 control groups.

| Factors | COVID-19-MDR-GNB n = 70 (%) |

COVID-19 n = 70 (%) |

Univariable analysis |

Multi-variable analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |||

| Age (years) | 58.0 (26–86) | 56.3 (36–90) | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Renal insufficiency | 23 (32.9) | 8 (11.4) | 3.79 (1.55–9.22) | 0.002 | 2.84 (1.03–7.80) | 0.043 |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 56 (80) | 43 (61.4) | 2.51 (1.17–5.36) | 0.016 | ||

| Central venous cateter | 37 (52.9) | 17 (24.3) | 3.49 (1.70–7.18) | 0.001 | ||

| Nasoenteral tube | 6 (8.6) | 0 | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.028a | ||

| Length of stay | 28.0 | 16.0 | ||||

| Up to 30 days | 53 (75.7) | 63 (90) | 0.34 (0.13–0.89) | 0.025 | 3.69 (1.25–10.91) | 0.018 |

| Use of antimicrobials | ||||||

| Carbapenems | 39 (55.7) | 22 (31.4) | 2.74 (1.37–5.47) | 0.004 | 3.48 (1.37–8.80) | 0.008 |

| Cephalosporin | 27 (38.5) | 40 (57.1) | 0.47 (0.24–0.92) | 0.028 | ||

| Aminoglycosides | 16 (22.8) | 5 (7.14) | 3.85 (1.32–11.19) | 0.009 | ||

| Polymyxins | 33 (47.1) | 10 (14.2) | 4.24 (1.86–9.64) | 0.001 | ||

| β-lactams | 33 (47.1) | 48 (68.6) | 0.40 (0.20–0.81) | 0.010 | 4.11 (1.63–10.33) | 0.003 |

| Deaths | 48 (68.6) | 25 (35.7) | 3.92 (1.94–7.92) | 0.000 | 3.29 (1.45–7.49) | 0.004 |

Fisher's Exact Test.

To analyze the factors associated with COVID-19 among patients with MDR-GNB, case patients (COVID-19-MDR-GNB) were compared to control group 2 (MDR-GNB). Univariate analysis demonstrated that obesity, cardiac insufficiency, mechanical ventilation, central venous catheter, age between 23 and 60 years, age over 60 years, β-lactam and polymyxins antimicrobials use were identified as factors associated with MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19 ( Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multi-variate analysis between COVID-19-MDR-GNB case atients compared to MDR-GNB control groups.

| Factors | COVID-19-MDR-GNB n = 70 (%) |

MDR-GNB n = 70 (%) |

Univariable analysis |

Multi-variable analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |||

| Age (years) | 58.0 (26–86) | 64.7 (23–92) | ||||

| 23–60 | 37 (52.8) | 25 (35.7) | 2.01 (1.02–3.97) | 0.041 | ||

| ≥ 61 | 33 (47.1) | 45 (64.2) | 0.45 (0.25–0.97) | 0.041 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Obesity | 10 (14.3) | 2 (2.9) | 5.66 (1.19–26.89) | 0.031a | ||

| Cardiac insufficiency | 7 (10) | 23 (32.9) | 4.40 (1.74–11.12) | 0.001 | 4.68 (1.59–13.73) | 0.005 |

| Hospitalization | 28.0 | 29.5 | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 56 (80) | 38 (54.3) | 3.36 (1.58–7.13) | 0.001 | 3.05 (1.28–7.26) | 0.011 |

| Central venous cateter | 37 (52.9) | 24 (34.3) | 2.14 (1.088–4.24) | 0.027 | ||

| Use of antimicrobials | ||||||

| Polymyxins | 33(47.1) | 29 (41.4) | 0.79 (0.40–1.54) | 0.496 | 0.41 (0.17–0.97) | 0.045 |

| β-lactams | 33 (47.1) | 51 (72.8) | 0.33 (0.16–0.67) | 0.002 | 4.22 (1.75–10.14) | 0.001 |

| Origin of culture | ||||||

| Tracheal secretion | 35 (50) | 12 (17.6) | 4.83(2.21–10.52) | 0.000 | ||

| Swabs retal | 17 (24.6) | 38 (55.9) | 0.27(0.13–0.55) | 0.000 | ||

| Microorganisms | ||||||

| Burkholderia cepacia | 7 (10) | 0 | 2.11 (1.76–2.52) | 0.013a | ||

| Deaths | 48 (68.6) | 35 (50) | 2.18 (1.09–4.34) | 0.025 | 2.47 (1.07–5.68) | 0.033 |

Fisher's Exact Test.

Additionally, in the multivariate analysis cardiac insufficiency and mechanical ventilation use were associated with MDR-GNB and COVID-19-MDR-GNB patients, respectively. The mortality rates of COVID-19-MDR-GNB patients were increased 2.47 when compared with MDR-GNB. Additionally, the use of polymyxin was a protective factor for the occurrence of MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19.

Case patients (COVID-19-MDR-GNB) were compared with the control group (GNB) to analyze the associated factors to secondary MDR-GNB infection in patients with COVID-19. In the univariate analysis, several covariates showed statistically significant associations, including systemic arterial hypertension; diabetes; renal insufficiency; acute respiratory failure; smoking; mechanical ventilation; urinary catheter; central venous catheter; nasoenteral tube; use of antimicrobials (β-lactams, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, cephalosporins, and polymyxins); and age between 18 and 60 and over 60 years ( Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multi-variate analysis between COVID-19-MDR-GNB patients compared to GNB control groups.

| Factors | COVID-19-MDR-GNB n = 70 (%) |

GNB n = 70 (%) |

Univariable analysis |

Multi-variable analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |||

| Age (years) | 58.0 (26–86) | 43.9 (18–91) | ||||

| 18–60 | 37 (52.8) | 51 (72.8) | 0.41 (0.20–0.84) | 0.014 | ||

| ≥ 61 | 33 (47.1) | 19 (11.4) | 2.39 (1.18–4.84) | 0.014 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 47 (67.1) | 18 (25.7) | 5.90 (2.83–12.27) | 0.000 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 33 (47.1) | 16 (22.9) | 3.01 (1.45–6.24) | 0.003 | 3.03 (1.09–8.38) | 0.032 |

| Diabetes | 23 (32.9) | 12 (17.1) | 2.36 (1.06–5.24) | 0.032 | ||

| Renal insufficiency | 23 (32.9) | 11 (15.7) | 2.62 (1.16–5.92) | 0.018 | 5.54 (1.29–23.82) | 0.021 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 10 (14.3) | 1 (1.4) | 11.50 (1.43–92.47) | 0.009a | ||

| Smoking | 0 | 6 (8.6) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) | 0.028a | ||

| Hospitalization | 28.0 | 17.1 | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 56 (80) | 18 (25.7) | 11.55 (5.22–25.56) | 0.000 | 17.85 (5.07–62.85) | 0.000 |

| Urinary cateter | 27 (38.6) | 9 (12.9) | 4.25 (1.82–9.95) | 0.001 | ||

| Central venous catheter | 37 (52.9) | 12 (17.1) | 5.41 (2.48–11.80) | 0.000 | ||

| Nasoenteral tube | 6 (8.6) | 0 | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.028a | ||

| Use of antimicrobials | ||||||

| Carbapenems | 39 (55.7) | 20 (28.5) | 3.14 (1.56–6.34) | 0.001 | ||

| Cephalosporin | 27 (38;5) | 41 (58.5) | 0.44 (0.22–0.87) | 0.018 | ||

| Polymyxins | 33 (47.1) | 6 (8.5) | 7.54 (2.88–19.75) | 0.000 | 3.24 (0.97–10.83) | 0.055 |

| β-lactams | 33 (47.1) | 46 (65.7) | 0.46 (0.23–0.91) | 0.027 | 0.08 (0.02–0.32) | 0.000 |

| Deaths | 48 (68.6) | 15 (21.4) | 8.00 (3.73–17.14) | 0.000 | 3.44 (1.22–9.67) | 0.019 |

Fisher's Exact Test.

Furthermore, in the multivariate analysis, systemic arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, mechanical ventilation, use of polymyxins and outcomes in deaths were associated with secondary MDR-GNB infection in patients with COVID-19, with an increase of 3.44 in the mortality rates. Additionally, the use of β-lactams was a protective factor for the occurrence of MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19.

Outcome study

Mortality was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB compared with COVID-19 controls (68.6% vs. 35.7%, respectively; p = 0.000, odds ratio [OR] 392, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.94–7.92), MDR-GNB (68.6% vs. 50%, respectively; p = 0.002, OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.16–0.67) and GNB (68.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively; p = 0.000, OR 8.00, 95% CI 3.73–17.14). Overall, mortality at 30 days for patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB was recorded at 57.1% (n = 40/70). A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed the cumulative probability of death in the 30 days was significantly different among the COVID-19-MDR-GNB, MDR-GNB, GNB, and COVID-19 patient groups (p = 0.008) and higher among patients infected with COVID-19-MDR-GNB strains ( Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier cumulative (cum) survival curve for 30-day mortality of MDR-GNB infection by log-rank test (p = 0.008). The red line represents patients with COVID-19 and infection caused by MDR-GNB strains, the green line represents patients with infection caused by MDR-GNB strains, the blue line represents patients with infection caused by GNB strains, and the black line represents patients with COVID-19.

Additionally, this study also aimed to identify factors associated with mortality. In a multivariate analysis of patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB, the use of a urinary catheter and exposure to polymyxin were associated with mortality. In contrast, systemic arterial hypertension and surveillance swabs were protective factors. While for patients with MDR-GNB, the use of carbapenems and the origin of the bacterial culture as tracheal secretion were factors associated with mortality. For patients with COVID-19, age over 60 years, renal failure, and central venous catheter use were associated with mortality ( Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of factors associated with mortality in cases patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB and COVID-19, MDR controls groups.

| Factors | Deaths n (%) |

Survivors n (%) |

Univariable analysis |

Multi-variable analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |||

| Total | 48 (68.5) | 22 (31.4) | |||||

| COVID-19-MDR-GNB | Comorbidities | ||||||

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 18 (37.5) | 15 (68.1) | 0.28 (0.09–0.81) | 0.017 | 0.15 (0.04–0.60) | 0.007 | |

| Hospitalization | |||||||

| Urinary cateter | 23 (47.9) | 4 (18.1) | 4.14 (1.21–14.05) | 0.020 | 6.00 (1.30–27.65) | 0.021 | |

| Central venous cateter | 30 (62.5) | 7 (31.8) | 3.57 (1.22–10.41) | 0.017 | |||

| Length of stay (days) | 20.5 | 37.8 | |||||

| Up to 30 days | 40 (83.3) | 13 (59.0) | 3.46 (1.10–10.81) | 0.028 | |||

| Use of antibiotics | |||||||

| Polymyxins | 28 (35.7) | 8 (11.4) | 4.89 (1.44–16.60) | 0.009 | 5.76 (1.36–24.42) | 0.017 | |

| Origin of culture | |||||||

| Swabs | 10 (20.8) | 9 (81.8) | 0.33 (0.10–1.01) | 0.049 | 0.23 (0.06–0.93) | 0.040 | |

| Total | 35 (50) | 35 (50) | |||||

| MDR-GNB | Use of antibiotics | ||||||

| Carbapenems | 23 (32.8) | 15 (21.42) | 2.55 (0.97–6.72) | 0.055 | 3.92 (1.27–12.11) | 0.017 | |

| Origin of culture | |||||||

| Tracheal secretion | 10 (14.2) | 2 (2.85) | 6.60 (1.32–32.84) | 0.023 | 7.70 (1.40–42.45) | 0.019 | |

| COVID-19 | Total | 25 (35.7) | 45 (64.2) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≥60 | 15 (60) | 15 (60) | 3.00 (1.09–8.25) | 0.031 | 4.59 (1.06–19.77) | 0.041 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Renal insufficiency | 6 (24) | 2 (4.4) | 6.78 (1.25–36.75) | 0.021 | 24.50 (2.96–202.54) | 0.003 | |

| Acute respiratory failure | 10 (40) | 2 (4.4) | 14.33 (2.81–73.00) | 0.000 | |||

| Hospitalization | |||||||

| Urinary catheter | 13 (52) | 4 (8.8) | 11.10 (3.05–40.42) | 0.000 | |||

| Central venous catheter | 14 (56) | 3 (6.6) | 17.81 (4.33–73.17) | 0.000 | 21.32 (4.29–105.82) | 0.000 | |

| Previous use of antibiotics | |||||||

| Cephalosporin | 9 (36) | 31 (68.8) | 0.25 (0.09–0.71) | 0.012 | |||

| Polymyxins | 6 (24) | 4 (8.8) | 3.23 (0.81–12.82) | 0.151 | 6.71 (1.06–42.46) | 0.043 | |

Treatment of patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB and MDR-GNB

Regarding antibiotic therapy, in COVID-19-MDR-GNB patients, 36 individuals received polymyxin B. Out of these, 27% (10/36) received monotherapy and 60% (6/10) died. On the other hand, 72.22% (26/36) polymyxin B combined with other antibiotics, and 84.61% (22/26) died. The most frequently combination therapies were polymyxin B and amikacin in 46% (12/26) and polymyxin B with meropenem in 34% (9/26), with the observed mortality rates was 75% (9/12) and 88.88% (8/9), respectively. Among MDR-GNB group, 29 patients received polymyxin B. Of those, 27.58% (8/29) received monotherapy and 62% (5/8) died. Polymyxin B combination was used in 72.41% (21/29) and 28.57% (6/21) of those patients died. No statistically significant difference was observed in therapy outcomes among the studied groups.

Regarding treatments, in the COVID-19-MDR-GNB group, 44 patients received corticosteroids such as dexamethasone, 15 dexamethasone and prednisone, and 6 prednisone. In addition, 15 patients were treated with azithromycin, 2 with oseltamivir and 2 with acyclovir. In the MDR-GNB group, 47 patients received dexamethasone, 14 dexamethasone and prednisone, and 2 prednisone. In addition, 37 patients were treated with azithromycin, 11 with oseltamivir and 2 with acyclovir.

Discussion

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, infections caused by MDR-GNB, including Enterobacteriaceae, P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii, represented a global public health concern owing to antimicrobial restriction and increased lethality [12], [22]. This problem was probably exacerbated during the pandemic since hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were generally vulnerable, staying hospitalized for long periods in ICU, requiring a greater number of invasive procedures, mechanical ventilation: factors that contribute to the risk of acquiring MDR-GNB [11], [13].

The ecology of microorganisms and their resistance patterns reflects the institutional epidemiological situation [15]. Our study showed that in the study, P. aeruginosa (29.4%), K. pneumoniae (22.7%), and A. baumannii (15.9%) were the main MDR-GNB species isolated in the hospital. In contrast, as per the reported data described in Taiwan, the most common isolates were E. coli (45,1%), K. pneumoniae (17.3%), and Acinetobacter spp. (14.3%) [9]. The pattern of resistance distribution among pathogens varies geographically, reinforcing the need for local estimates to adapt local responses to the control of MDR-GNB [4].

Additionally, when analyzing the pathogens among patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB, we identified K. pneumoniae (31.4%), A. baumannii (29.1%), and P. aeruginosa (16.6%) as the main pathogens isolated in patients who died. This same pattern of main pathogens was observed among patients with MDR-GNB, although with non-identical rates, namely, K. pneumoniae (42.8%), A. baumannii (20%), and P. aeruginosa (11.4%). Infections caused by resistant Enterobacteriaceae are associated with increased mortality [15], [23]. Previous studies described that the mortality rate among patients with resistant K. pneumoniae infections is high, ranging from 28.6% to 66.6% [6], [24].

In our study, MDR-GNB isolation in patients with COVID-19 was associated with mortality. In addition, in Qatar, mechanical ventilation (p = 0.015, OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.11) was described as a risk factor associated with the isolation of MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB (n = 78) [13]. Additionally, in Spain, a retrospective case-control study assessed patients with COVID-19 and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infection (n = 30), compared to patients without COVID-19 and CRE (n = 24) and identified a 30-day mortality rate of 30% and 16.7%, respectively (p = 0.25). Additionally, K. pneumoniae (80.8%), Serratia marcescens (11%), and Enterobacter cloacae (4.1%) were the most frequent bacteria isolated in these groups [15].

Several risk factors have been described associated with MDR-GNB, including previous use of antibiotics, use of carbapenem, mechanical ventilation, intubation, previous hospitalization, dialysis, use of invasive devices, longer ICU stay, and presence of underlying comorbidities [25]. Additionally, in patients with COVID-19, risk factors associated with mortality have been described associated with men; smokers; age ≥ 60 years, and comorbidities such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, hypercholesterolemia; and ICU admission [26], [27]. Thus, the occurrence of these factors is determinant, making patients subject to risks of acquiring MDR-GNB infections and/or greater complications owing to COVID-19.

Hypertension and cardiovascular disease were described as risk factors associated with the progression of COVID-19 [28]. However, in our study systemic arterial hypertension was a protective factor against mortality in patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB. The underlying effects of antihypertensive treatments, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), have been investigated and shown to increase intrinsic antiviral cellular responses and the cell-epithelial-immune interactions, respectively [29]. Thus, further studies are needed to improve the understanding of these variables.

Furthermore, 30-day mortality rates for patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB and COVID-19 were 57.1% and 34.2%, respectively. The worrying mortality rates identified in our study highlight the need for isolation and identification of the early susceptibility profile of these microorganisms to initiate adequate treatment against these MDR-GNB, which can be potentially fatal in patients with COVID-19. In Taiwan, the 30-day mortality rate among patients with MDR-GNB bacteremia versus patients without MDR-GNB was 27.4% and 13%, respectively [30]. Thus, in our study, the occurrence of MDR-GNB negatively impacted the prognosis of patients with COVID-19, increasing the 30-day mortality. This data is particularly important for hospital infection control services, reinforcing the need for measures to prevent and control the transmission of MDR-GNB, especially among critically ill patients, to improve outcomes and hospital survival.

Our findings demonstrate that in patients with COVID-19-MDR-GNB, polymyxin exposure and urinary catheter were independently associated with mortality, increasing the risks by 5.7 and 6.0-fold, respectively. In contrast, in patients with MDR-GNB, factors associated with mortality were the use of carbapenems and bacterial origin of tracheal secretion, increasing the risks by 3.9 and 7.7-fold, respectively. Additionally, in patients with COVID-19, age over 60 years, use of polymyxin, central venous catheter use, and renal failure are factors associated with mortality, increasing the risks by 4.5, 6.7, 21.3, and 24.5 times, respectively. In the United States and Taiwan, longer hospital stay, surgical re-exploration, urinary catheter as a source of infection, exposure of antibiotics, and use of carbapenems and fluoroquinolones were identified as independent factors associated with MDR-GNB infection [9], [31]. Therefore, procedures to prevent MDR-GNB infection in patients with COVID-19 should include minimizing the use of invasive devices to improve the prognosis [13].

Despite all the control measures instituted in hospitals, patients with COVID-19 may still be at increased risk of secondary bacterial infections with MDR pathogens. They are often exposed to risk factors such as invasive devices, mechanical ventilation, prolonged ICU stay, and extensive use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials [32], [33]. A systematic review evaluated risk factors related to mortality in patients with COVID-19. Chronic comorbidities, acute kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, male sex, advanced age, current smoking, and obesity are associated with lethality [34]. Others studies also reported that secondary bacterial infection has been associated with a negative impact on prognosis in patients with COVID-19 [35], [36], [37].

Our study, the percentage of mortality among patients with COVID-19 was 35.7, corroborating the literature [26]. Mortality among patients with MDR-GNB and GNB was 50% and 21.4%, respectively. Notably, patients with secondary MDR-GNB infection had a substantially higher case fatality rate to 68.7%, imposing a huge burden on healthcare facilities, particularly for those with comorbidities. Improving awareness and early recognition of MDR-GNB infections is crucial, as they can be fatal in COVID-19 patients; identifying at-risk patients and developing surveillance and prevention strategies are necessary to limit their impact.

Another case-control study conducted in Curitiba, southern Brazil, aimed to identify risk factors associated with the acquisition MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19. Male gender, desaturation, mechanical ventilation and hospital admission were identified as independent risk factors for MDR-GNB in patients with COVID-19 [38]. In contrast, our study covered a broader range of patients with MDR-GNB infections, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis of the results, including mortality in each group. The analysis of mortality is an important indicator of the severity of infections and can help identify the effectiveness of treatment and prevention measures. Therefore, both studies underscore the significance of identifying and preventing MDR-GNB infections in patients with COVID-19.

The effective infection control measures in healthcare settings need to be improved. Thus, prospective surveillance studies that systematically and continuously follow patients and/or populations at risk need to be encouraged. Understand the epidemiology and impact of MDR-GNB infections, assess the spread, monitor trends, and evaluate the impact on the hospital environment, may be help implement the preventive and therapeutic interventions [39], [40].

It is important to highlight that the clinical outcomes reported here should be interpreted with caution since the present study did not aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the aforementioned antibiotic combinations. We only describe the frequency of use and the clinical results of patients who underwent these treatments. Other clinical factors, such as age, comorbidities, and disease severity, among others, may have influenced the observed clinical results.

The limitations of our study should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Firstly, this is a retrospective study performed in a single hospital, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings. Therefore, future prospective and multicenter studies are needed to explore potential geographical variations in microbiological epidemiology. Secondly, although the number of patients transferred from other health units was not used as a stratification criterion, this could still impact our findings.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the significant impact of MDR-GNB in mortality, particularly among critically ill patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the occurrence of MDR-GNB increases mortality among patients with COVID-19. Our data reinforce the need to prevent the spread of these strains within the hospital environment, aiming to minimize these risks. Thus, these findings are important health indicators for hospitalized patients with COVID-19, emphasizing the need of surveillance and strategies to reduce the impact of MDR-GNB, especially in hospitalized patients.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted with the approval of the Research Ethics Committee from the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (number 4.014.325/2020).

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted with the approval of the Research Ethics Committee from Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (4.255.410/2020).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (401727/2020-3, 408778/2022-9, and 307946/2022-3), Fundação de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento do Ensino, Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul (325/2022 and 76/2023), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (001).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gleyce Hellen de Almeida de Souza: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation; Alexandre Ribeiro de Oliveira: Methodology, Investigation; Marcelo dos Santos Barbosa and Luana Rossato: Writing - Review & Editing and Supervision; Kerly da Silva Barbosa: Investigation; Simone Simionatto: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2023.05.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Minarini L.A.D.R., Andrade L.N. de, De Gregorio E., Grosso F., Naas T., Zarrilli R., et al. Editorial: antimicrobial resistance as a global public health problem: how can we address It? Front Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.612844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilahun M., kassa Y., Gedefie A., Belete M.A. Emerging carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae infection, its epidemiology and novel treatment options: a review. IDR. 2021;14:4363–4374. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S337611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill J. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations 2016.

- 4.Murray C.J., Ikuta K.S., Sharara F., Swetschinski L., Robles Aguilar G., Gray A., et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Da Silva K.E., Maciel W.G., Sacchi F.P.C., Carvalhaes C.G., Rodrigues-Costa F., da Silva A.C.R., et al. Risk factors for KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: watch out for surgery. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65:547–553. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Da Silva K.E., Baker S., Croda J., Nguyen T.N.T., Boinett C.J., Barbosa L.S., et al. Risk factors for polymyxin-resistant carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in critically ill patients: An epidemiological and clinical study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ukuhor H.O. The interrelationships between antimicrobial resistance, COVID-19, past, and future pandemics. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velazquez-Meza M.E., Galarde-López M., Carrillo-Quiróz B., Alpuche-Aranda C.M. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet World. 2022:743–749. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.743-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin T.-L., Chang P.-H., Chen I.-L., Lai W.-H., Chen Y.-J., Li W.-F., et al. Risk factors and mortality associated with multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infection in adult patients following abdominal surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2022;119:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelfrene E., Botgros R., Cavaleri M. Antimicrobial multidrug resistance in the era of COVID-19: a forgotten plight? Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13756-021-00893-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jean S.-S., Harnod D., Hsueh P.-R. Global threat of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.823684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baiou A., Elbuzidi A.A., Bakdach D., Zaqout A., Alarbi K.M., Bintaher A.A., et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for the isolation of multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Infect. 2021;110:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannou G.N., Locke E., Green P., Berry K., O’Hare A.M., Shah J.A., et al. Risk factors for hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or death among 10 131 US veterans with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pintado V., Ruiz-Garbajosa P., Escudero-Sanchez R., Gioia F., Herrera S., Vizcarra P., et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales infections in COVID-19 patients. Infect Dis. 2022;54:36–45. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1963471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ANVISA, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Microbiologia Clínica para o Controle de Infecção Relacionada a Assistência à saúde. Procedimentos Laboratoriais: Da Requisição Do Exame a Análise Microbiológica e Laudo Final 2013.

- 17.Magiorakos A.-P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.B., Carmeli Y., Falagas M.E., Giske C.G., et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horan T.C., Andrus M., Dudeck M.A. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes S., Troise O., Donaldson H., Mughal N., Moore L.S.P. Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1395–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll K.C., Glanz B.D., Borek A.P., Burger C., Bhally H.S., Henciak S., et al. Evaluation of the BD phoenix automated microbiology system for identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3506–3509. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00994-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CLSI C& LSI. Performance Standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (M100). 2020.

- 22.Jabbour J.-F., Sharara S.L., Kanj S.S. Treatment of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative skin and soft tissue infections: Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2020:1. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000635. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Liu J., Zhang L., Pan J., Huang M., Li Y., Zhang H., et al. Risk factors and molecular epidemiology of complicated intra-abdominal infections with carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae: a multicenter study in China. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:S156–S163. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montrucchio G., Corcione S., Sales G., Curtoni A., De Rosa F.G., Brazzi L. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in ICU-admitted COVID-19 patients: Keep an eye on the ball. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;23:398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palacios-Baena Z.R., Giannella M., Manissero D., Rodríguez-Baño J., Viale P., Lopes S., et al. Risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grasselli G., Greco M., Zanella A., Albano G., Antonelli M., Bellani G., et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1345. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiang G., Xie L., Chen Z., Hao S., Fu C., Wu Q., et al. Clinical risk factors for mortality of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:2723–2735. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng M., He J., Xue Y., Yang X., Liu S., Gong Z. Role of hypertension on the severity of COVID-19: a review. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2021;78:e648–e655. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trump S., Lukassen S., Anker M.S., Chua R.L., Liebig J., Thürmann L., et al. Hypertension delays viral clearance and exacerbates airway hyperinflammation in patients with COVID-19. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:705–716. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-00796-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ting S.-W., Lee C.-H., Liu J.-W. Risk factors and outcomes for the acquisition of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacillus bacteremia: A retrospective propensity-matched case control study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018;51:621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patolia S., Abate G., Patel N., Patolia S., Frey S. Risk factors and outcomes for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli bacteremia. Ther Adv Infect. 2018;5:11–18. doi: 10.1177/2049936117727497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomez-Simmonds A., Annavajhala M.K., McConville T.H., Dietz D.E., Shoucri S.M., Laracy J.C., et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales causing secondary infections during the COVID-19 crisis at a New York City hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76:380–384. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasero D., Cossu A.P., Terragni P. Multi-drug resistance bacterial infections in critically Ill patients admitted with COVID-19. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1773. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9081773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dessie Z.G., Zewotir T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:855. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saeed N.K., Al-Khawaja S., Alsalman J., Almusawi S., Albalooshi N.A., Al-Biltagi M. Bacterial co-infection in patients with SARS-CoV-2 in the Kingdom of Bahrain. WJV. 2021;10:168–181. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v10.i4.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohammadnejad E., Manshadi S.A.D., Taghi Beig Mohammadi M., Abdollai A., Seifi A., Salehi M.R., et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in Covid-19 patients admitted to the intensive care unit of Imam Khomeini complex hospital in Tehran. IJM. 2021 doi: 10.18502/ijm.v13i6.8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shafran N., Shafran I., Ben-Zvi H., Sofer S., Sheena L., Krause I., et al. Secondary bacterial infection in COVID-19 patients is a stronger predictor for death compared to influenza patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:12703. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Macedo V., dos Santos G., de S., da Silva R.N., Couto C.N., de M., et al. The health facility as a risk factor for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Clinics. 2022;77 doi: 10.1016/j.clinsp.2022.100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tacconelli E., Cataldo M.A., Dancer S.J., De Angelis G., Falcone M., Frank U., et al. ESCMID guidelines for the management of the infection control measures to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in hospitalized patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:1–55. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray J., Cohen A.L. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Elsevier,; 2017. Infectious disease surveillance; pp. 222–229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material