Abstract

BACKGROUND

Early in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there was a significant impact on routine medical care in the United States, including in fields of transplantation and oncology.

AIM

To analyze the impact and outcomes of early COVID-19 pandemic on liver transplantation (LT) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States.

METHODS

WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. We retrospectively analyzed data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database regarding adult LT with confirmed HCC on explant in 2019 and 2020. We defined pre-COVID period from March 11 to September 11, 2019, and early-COVID period as from March 11 to September 11, 2020.

RESULTS

Overall, 23.5% fewer LT for HCC were performed during the COVID period (518 vs 675, P < 0.05). This decrease was most pronounced in the months of March-April 2020 with a rebound in numbers seen from May-July 2020. Among LT recipients for HCC, concurrent diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis significantly increased (23 vs 16%) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD) significantly decreased (18 vs 22%) during the COVID period. Recipient age, gender, BMI, and MELD score were statistically similar between two groups, while waiting list time decreased during the COVID period (279 days vs 300 days, P = 0.041). Among pathological characteristics of HCC, vascular invasion was more prominent during COVID period (P < 0.01), while other features were the same. While the donor age and other characteristics remained same, the distance between donor and recipient hospitals was significantly increased (P < 0.01) and donor risk index was significantly higher (1.68 vs 1.59, P < 0.01) during COVID period. Among outcomes, 90-day overall and graft survival were the same, but 180-day overall and graft were significantly inferior during COVID period (94.7 vs 97.0%, P = 0.048). On multivariable Cox-hazard regression analysis, COVID period emerged as a significant risk factor of post-transplant mortality (Hazard ratio 1.85; 95%CI: 1.28-2.68, P = 0.001).

CONCLUSION

During COVID period, there was a significant decrease in LTs performed for HCC. While early postoperative outcomes of LT for HCC were same, the overall and graft survival of LTs for HCC after 180 days were significantly inferior.

Keywords: Liver transplantation, Hepatocellular carcinoma, COVID-19, Mortality, Graft failure, United Network for Organ Sharing database

Core Tip: Overall, 23.5% fewer liver transplants for hepatocellular carcinoma were performed during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) early pandemic. Among liver transplant recipients for hepatocellular carcinoma, concurrent diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis significantly increased. Liver transplant outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma was worse during the early COVID-19 pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

Since December 2019, after an initial cluster of cases of pneumonia was reported in Wuhan, China, the global spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was swift, and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. This pandemic significantly impacted healthcare in the United States including transplantation[1,2] and cancer care[3], especially early in the pandemic when there were challenges in access to routine healthcare[4]. While the number of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) including alcoholic hepatitis increased during the pandemic, liver transplantation (LT) for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were postponed due to the lower severity of the underlying liver disease[5]. The aim of this study was to analyze the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on LT for HCC in the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and selection criteria

We evaluated all patient 18 years of age and older undergoing LT who were confirmed as HCC on pathology in the United States. Since WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, we defined pre-COVID period as March 11 to September 11, 2019, and COVID period as March 11 to September 11, 2020. Patients who received re-transplant during the study were excluded. All study methods were approved by New York Medical College Institutional Review Board.

Patient characteristics and outcome variables

All data were collected from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry. Demographic data included diagnosis, age, gender and race. Evaluable recipient factors included body mass index (BMI), underlying etiology for liver disease, pre-transplant diabetes mellitus (DM) status, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, presence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score at transplant. Milan criteria and UCSF criteria were created based on the pathological findings[6,7]. HCC related factors included tumor size, number, presence of vascular invasion, and histological grade. High risk features of HCC were defined if one or more of the followings were present: More than 3 tumors, largest tumor > 5.0 cm, presence of vascular invasion, presence of metastases, and poorly differentiated[8]. Donor related factors included donor causes of death, BMI, hepatitis C virus (HCV) sero-status, cold ischemia time, distance between donor and recipient hospitals, and donor risk index[9].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and R studio version 4.1.1 (R Studio, Inc., Boston, MA, United States). Non-parametric analysis was used to compare continuous variables between groups (Mann-Whitney U test 2 groups and for categorical data with the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data). The overall and graft survival were calculated from the date of transplant to the date of event using the Kaplan-Meier Method. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Cox regression analysis was applied to assess the association of multiple covariate factors with survival between two groups. Results were presented as hazard ratios (HR) and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and two-sided P values. For all statistical analyses, P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Recipient characteristics

During the study period, a total of 8384 individuals received LT, of which 1193 were confirmed as HCC on explant pathology. Of these patients, 675 underwent transplantation during the pre-COVID period and 518 underwent transplantation during the COVID period (Table 1). While there was a 4% reduction in all-cause LT during the COVID period, the reduction of LT for HCC was 23.5%. This decrease was most pronounced in months of March-April 2020 with a rebound in numbers seen from May-July 2020. Compared to pre-COVID period, the concurrent underlying primary etiology of liver disease among LT recipients for HCC showed a significant increase in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (23% vs 16%) and significant decrease in ALD (18% vs 22%) during the COVID period. The median waiting list time among patients who underwent LT, decreased during the COVID period (279 days vs 300 days, P = 0.041). There were no significant differences in the rates of pre-transplant diabetes, AFP levels, and MELD score at transplant between the two periods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, n (%)

|

Variable

|

COVID, n = 518

|

Pre-COVID, n = 675

|

P

value |

| Recipient | |||

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 64.0 (60.0, 67.8) | 63.0 (59.0, 67.0) | 0.2 |

| Male | 405 (78) | 529 (78) | 0.98 |

| Race, White | 328 (63) | 388 (57) | 0.12 |

| African American | 36 (6.9) | 47 (7.0) | |

| Hispanic | 108 (21) | 153 (23) | |

| Asian | 39 (7.5) | 69 (10) | |

| Others | 7 (1.4) | 19 (2.8) | |

| BMI median (IQR) kg/m2 | 29.3 (25.7, 33.2) | 28.9 (25.3, 33.0) | 0.26 |

| Etiology, HCV | 180 (35) | 258 (38) | 0.034 |

| HBV | 33 (6.4) | 43 (6.4) | |

| ALD | 95 (18) | 149 (22) | |

| NASH | 118 (23) | 107 (16) | |

| Others | 92 (18) | 118 (17) | |

| Blood Type, A | 203 (39) | 235 (35) | 0.13 |

| AB | 18 (3.5) | 27 (4.0) | |

| B | 76 (15) | 82 (12) | |

| O | 221 (43) | 331 (49) | |

| Diabetes | 208 (40) | 255 (38) | 0.4 |

| HCV positive serostatus | 229 (46) | 319 (49) | 0.28 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 229 (45) | 330 (49) | 0.19 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 66 (13) | 106 (16) | 0.19 |

| Hemodialysis at transplant | 8 (1.6) | 8 (1.2) | 0.59 |

| TIPSS | 30 (5.8) | 32 (4.7) | 0.42 |

| AFP ng/mL, median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0, 15.0) | 7.0 (4.0, 16.0) | 0.21 |

| MELD score, median (IQR) | 10 (8, 14) | 10 (8, 14) | 0.33 |

| MELD exception | 510 (98) | 658 (97) | 0.24 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | 0.51 |

| Waiting days, median (IQR) | 279 (221, 392) | 300 (228, 424) | 0.041 |

| Patient location at transplant | 0.62 | ||

| ICU at time of transplant | 2 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Non-ICU inpatient at time of transplant | 19 (3.7) | 31 (4.6) | |

| Outpatient | 487 (96) | 639 (95) | |

| Donor | |||

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 45.0 (32.0, 59.0) | 44.0 (30.0, 56.0) | 0.027 |

| Male | 326 (63) | 421 (62) | 0.84 |

| Race, White | 322 (62) | 428 (63) | 0.058 |

| African American | 104 (20) | 117 (17) | |

| Hispanic | 73 (14) | 92 (14) | |

| Asian | 15 (2.9) | 17 (2.5) | |

| Others | 4 (0.8) | 21 (3.1) | |

| BMI median (IQR) kg/m2 | 27.8 (24.4, 33.2) | 27.0 (23.8, 30.9) | < 0.001 |

| Blood Type, A | 204 (39) | 237 (35) | 0.12 |

| AB | 14 (2.7) | 16 (2.4) | |

| B | 80 (15) | 88 (13) | |

| O | 220 (42) | 334 (49) | |

| HCV NAT positive | 37 (7.1) | 39 (5.8) | 0.34 |

| HCV antibody positive | 59 (11) | 76 (11) | 0.94 |

| Donor causes of death: Anoxia | 234 (45) | 265 (39) | 0.026 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 158 (31) | 221 (33) | |

| Head trauma | 104 (20) | 172 (25) | |

| Central nervous system tumor | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | |

| Others | 20 (3.9) | 13 (1.9) | |

| Donor after cardiac death | 62 (12) | 80 (12) | 0.95 |

| Organ Share, Local | 241 (47) | 508 (75) | < 0.001 |

| Regional | 174 (34) | 145 (21) | |

| National | 103 (20) | 22 (3.3) | |

| Donor risk index, median (IQR) | 1.68 (1.45, 2.06) | 1.59 (1.35, 1.91) | < 0.001 |

COVID: Coronavirus disease; IQR: Interquartile range; BMI: Body mass index; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; TIPSS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; ICU: Intensive care units; NAT: Nucleic acid amplification test.

Donor characteristics

The donor age (COVID 45 years-old vs pre-COVID 44 years-old, P = 0.027) and BMI (27.8 kg/m2 vs 27.0 kg/m2, P < 0.001) were significantly higher during the COVID period (Table 1). Although the distance between donor and recipient hospitals significantly increased during COVID period (88 miles vs 50 miles, P < 0.001), cold ischemia time was not significantly affected (5.87 hours vs 5.78 h, P = 0.84). The donor risk index was significantly higher during the COVID period (1.68 vs 1.59, P < 0.01) (Table 1).

Tumor characteristics

During the COVID period, the overall number of tumors with equal or greater than one high-risk features was the same (Table 2). However, there was a significantly higher rate of vascular invasion during the COVID period compared to pre-COVID period (16% vs 11%, P = 0.016). There were no significant differences in histological grade, outside of Milan criteria, and outside of UCSF criteria during the both periods.

Table 2.

Pathological characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in liver transplant, n (%)

|

Variable

|

COVID, n = 518

|

Pre-COVID, n = 675

|

P

value |

| Number of tumors | |||

| 1 | 229 (44) | 333 (49) | |

| 2 | 116 (22) | 146 (22) | |

| 3 | 80 (15) | 77 (11) | |

| 4 | 36 (6.9) | 47 (7.0) | |

| 5 | 22 (4.2) | 33 (4.9) | |

| 6 | 31 (6.0) | 38 (5.6) | |

| Tumor numbers > 3 | 89 (17) | 118 (17) | 0.89 |

| Outside UCSF criteria | 131 (25) | 178 (26) | 0.71 |

| Outside Milan criteria | 203 (39) | 262 (39) | 0.84 |

| Tumor max size, cm median (IQR) | 2.80 (1.80, 4.00) | 2.90 (1.90, 4.00) | 0.92 |

| Worst tumor histology | |||

| Complete tumor necrosis | 132 (25) | 185 (27) | 0.5 |

| Moderate differentiated | 265 (51) | 344 (51) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 26 (5.0) | 41 (6.1) | |

| Well differentiated | 95 (18) | 105 (16) | |

| Vascular invasion | 6 (1.2) | 11 (1.6) | 0.019 |

| Macro | |||

| Micro | 77 (15) | 65 (9.6) | |

| None | 435 (84) | 599 (89) | |

| Lymph node involvement | 8 (1.5) | 4 (0.6) | 0.1 |

| Extra hepatic spread | 7 (1.4) | 6 (0.9) | 0.76 |

| Intrahepatic metastasis | 42 (8.1) | 36 (5.3) | 0.066 |

| Previous treatment for HCC | 511 (99) | 657 (97) | 0.21 |

| High risk features | 174 (34) | 198 (29) | 0.12 |

COVID: Coronavirus disease; IQR: Interquartile range; UCSF: University of California San Francisco; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

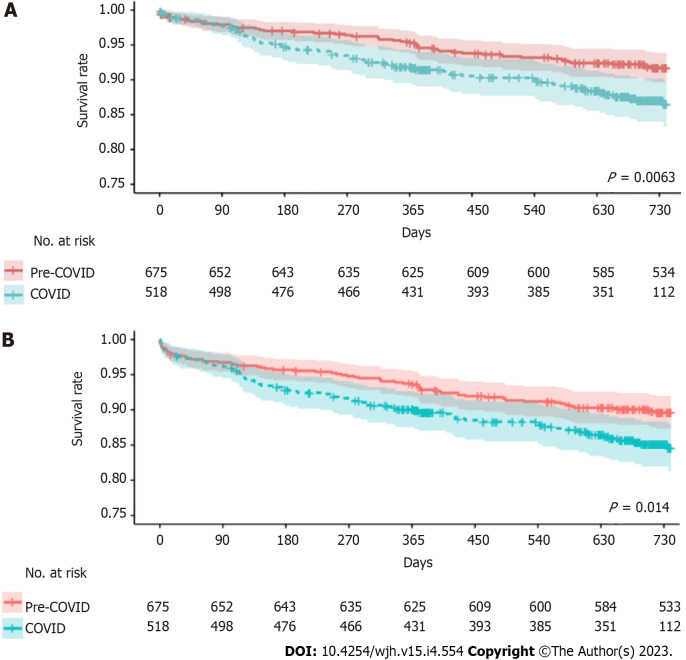

Outcomes

Median follow-up period was 705 days in COVID period and 1059 days in pre-COVID period. Two-year overall survival (COVID period 86.5% vs pre-COVID 91.7%, P = 0.0063) and graft survival (COVID period 84.5% vs pre-COVID 89.6%, P = 0.014) were significantly inferior during the COVID period (Figure 1) (Table 3). The 180-day overall survival (COVID period 94.7% vs pre-COVID 97.0%, P = 0.048) and graft survival (COVID period 92.8% vs pre-COVID 95.7%, P = 0.035) were inferior during the COVID period. The 90-day overall survival (COVID period 97.7% vs pre-COVID 97.9%, P = 0.95) and graft survival (COVID period 96.1% vs pre-COVID 96.7%, P = 0.71) were comparable between the two periods. The risk of acute rejection after transplant before discharge was the same between pre-COVID and COVID period (17 vs 11, P = 0.061) and incidence of treatment of rejection within 6 months and 1 year were same.

Figure 1.

Post-transplant survival curves between pre-coronavirus disease and coronavirus disease period. A: Comparison of overall survival between pre-coronavirus disease (COVID) and COVID period; B: Comparison of graft survival between pre-COVID and COVID period.

Table 3.

Outcomes of liver transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma, n (%)

|

Variable

|

COVID, n = 518

|

Pre COVID, n = 675

|

P

value |

|

| Month | March | 68 (13) | 132 (20) | 0.008 |

| April | 86 (17) | 123 (18) | ||

| May | 108 (21) | 97 (14) | ||

| June | 78 (15) | 95 (14) | ||

| July | 84 (16) | 99 (15) | ||

| August | 94 (18) | 129 (19) | ||

| Distance from donor hospital, miles, median (IQR) | 88 (23, 188) | 50 (8, 164) | < 0.001 | |

| Cold ischemia time, hours median (IQR) | 5.87 (4.71, 7.07) | 5.78 (4.65, 7.12) | 0.84 | |

| Acute rejection before discharge | 17 (3.3) | 11(1.6) | 0.061 | |

| Treatment rejection within 6 month | 27 (6.4) | 38 (6.6) | 0.88 | |

| Treatment rejection within 1 year | 35 (8.4) | 45 (8.4) | 0.99 | |

| Length of stay, days median (IQR) | 8 (6, 11) | 8 (6, 12) | 0.60 | |

| Survival rate | ||||

| 90-day overall survival | 97.7 | 97.9 | 0.95 | |

| 180-day overall survival | 94.7 | 97.0 | 0.048 | |

| Two-year overall survival | 86.5 | 91.7 | 0.0063 | |

| 90 day graft survival | 96.1 | 96.7 | 0.71 | |

| 180 day graft survival | 92.8 | 95.7 | 0.035 | |

| Two-year graft survival | 84.5 | 89.6 | 0.014 | |

IQR: Interquartile range; COVID: Coronavirus disease.

Cox regression analysis was performed for overall survival and graft survival (SupplementaryTable 1 and 2). On multivariable analysis (Table 4), COVID period (HR, 1.85; 95%CI: 1.28-2.68, P = 0.001), recipient diabetes (HR 1.47; 95%CI: 1.04-2.06, P = 0.027), MELD score at transplant (HR, 1.04; 95%CI: 1.01-1.07, P = 0.016) significantly impacted recipient overall survival. On pathology, intrahepatic metastasis (HR 2.03; 95%CI: 1.20-3.42, P = 0.008) and poorly differentiated cancer (HR 2.76; 95%CI: 1.48-5.15, P = 0.001) significantly impacted recipient overall survival.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis of factors affecting overall mortality

|

Variable

|

HR

|

95%CI

|

P

value |

| COVID period | 1.85 | 1.28, 2.68 | 0.001 |

| Recipient age | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 0.15 |

| Recipient diabetes | 1.47 | 1.04, 2.06 | 0.027 |

| MELD score | 1.04 | 1.01, 1.07 | 0.016 |

| Donor age | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.02 | 0.10 |

| Donation after cardiac death | 0.59 | 0.31, 1.14 | 0.12 |

| Pathology | |||

| Intrahepatic metastasis | 2.03 | 1.20, 3.42 | 0.008 |

| Lymph node invasion | 2.49 | 0.90, 6.86 | 0.078 |

| Worst tumor histology | |||

| Complete tumor necrosis | reference | - | |

| Well differentiated | 1.11 | 0.63, 1.97 | 0.70 |

| Moderate differentiated | 1.27 | 0.81, 1.99 | 0.30 |

| Poorly differentiated | 2.76 | 1.48, 5.15 | 0.001 |

HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence intervals; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; COVID: Coronavirus disease.

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to examine the effect of COVID-19 on LT for HCC in the United States using the UNOS database. During COVID period, there was a significant reduction in the number of LTs performed for HCC compared to pre-COVID period. Even with overall reduction in the number LTs performed during the same period, the decrease was much pronounced in patients with underlying HCC (4% decrease in all-cause LT vs 23.5% decrease in LT for HCC). In addition, both graft and patient survival after 180 days during COVID period were significantly inferior compared to pre-COVID period.

During early pandemic, the unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on healthcare system disrupted both transplantation and oncological care. Due to resource reallocation, cancer patients experienced delays in diagnosis and treatment, as well as treatment interruptions including surgery and chemotherapy[3,4]. HCC is an aggressive form of liver cancer which requires a prompt, multimodal approach for diagnosis and management. Similar to outpatient management of other cancers, challenges in care of HCC were prompted by overall disruption of healthcare during COVID-19[10,11]. Despite efforts to optimize care, there was an overall reduction in HCC surveillance and subsequent treatment during the early COVID pandemic[12-14]. Because of the unknown risk-benefit of proceeding with liver transplantation and introducing iatrogenic immune-suppression, liver transplantation was limited to patients who had higher risk of imminent death while on the waitlist[1,2]. Since LT candidates for HCC often had lower MELD scores, this likely contributed to the disproportional decrease in LT for HCC during early COVID period.

The current leading indication for liver transplant in the United States is ALD[15]. During the COVID pandemic, there was a significant increase in alcohol misuse, which resulted higher rates of hospitalization from ALD, progression to fulminant liver disease and LT for acute and chronic ALD[16,17]. However, when looking at the underlying primary etiology of HCC for patients who received LT for HCC, the number and ratio of ALD significantly decreased during the COVID, while the number and ratio of NASH significantly increased. Though further studies are needed to investigate the cause of this seemingly contradictory finding, one possible explanation is increased alcohol recidivism in HCC patients with ALD as the primary underlying etiology, which could disqualify them as LT candidates in most transplant centers.

Similar to the decrease in graft and patient survival seen in all-cause LT during the early COVID period[5], the cause for significant decrease in graft and patient survival after 180 days in LT for HCC is likely multifactorial. During early COVID, many centers decreased the use of immunosuppression to mitigate the risk of infection[18]. Such conservative approaches may have contributed to increased rates of acute rejection prior to discharge[5]. In our cohort, although it is not statistically significant, we observed a similar trend in increased rates of rejection prior to discharge in those who were transplanted during COVID period. During the follow up, the incidences of acute rejection were comparable between pre-COVID and COVID period.

Another potential contributing factor towards inferior graft and patient survival in LT for HCC during the COVID period is the progression of HCC at the time of LT. Although there were no significant differences in histological grade and the number of patients outside Milan/USCF criteria, there was a significantly higher rates of vascular invasion during the COVID period compared to pre-COVID period. Vascular invasion is one of the known risk factors for recurrent HCC and detection of metastasis post-LT, which is associated with high morbidity and mortality[19]. As delays in oncological care and radiological testing were prevalent during this period, any such delay may have resulted in progression of HCC which was not grossly evident prior to LT.

In February 2020, the new liver allocation policy was also implemented which allowed for broader sharing of the organs across different organ procurement organizations[20]. This likely contributed to increase in donor risk index and farther distances between donor and recipient hospitals. Long term impact of these factors on the graft and overall outcomes still needs to be determined.

Limitations

This study was performed retrospectively using UNOS database. Other indirect effects of COVID-19, such as psychosocial impact, medication non-compliance, rates of recidivism of alcohol use, rates of community/household spread of COVID-19 are not available in the database and may impact the outcomes.

CONCLUSION

During the early-COVID period (from March 11, 2020 to September 11, 2020), the overall number of LT for HCC decreased and post-transplant graft and patient survival were inferior compared to pre-COVID period.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic significantly impacted healthcare in the United States including transplantation and cancer care, especially early in the pandemic when there were challenges in access to routine healthcare.

Research motivation

To analyze the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Liver transplantation (LT) for Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States.

Research objectives

All patient 18 years of age and older undergoing LT who were confirmed as HCC on pathology in the United States.

Research methods

Since WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, we defined pre-COVID period as March 11 to September 11, 2019, and COVID period as March 11 to September 11, 2020.

Research results

Overall, 23.5% fewer LT for HCC were performed during the COVID period (518 vs 675, P < 0.05). Among pathological characteristics of HCC, vascular invasion was more prominent during COVID period (P < 0.01), while other features were the same. Among outcomes, 90-day overall and graft survival were the same, but 180-day overall and graft were significantly inferior during COVID period (94.7 vs 97.0%, P = 0.048). On multivariable Cox-hazard regression analysis, COVID period emerged as a significant risk factor of post-transplant mortality (Hazard ratio 1.85; 95%CI: 1.28-2.68, P = 0.001).

Research conclusions

During COVID period, there was a significant decrease in LTs performed for HCC. While early postoperative outcomes of LT for HCC were same, the overall and graft survival of LTs for HCC after 180 days were significantly inferior.

Research perspectives

To analyze the effects of COVID-19 pandemic in the long-term effects for LT for HCC.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: All study methods were approved by New York Medical College Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was waived for patients in the study because of the study's retrospective nature and the use of a retrospective database.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Peer-review started: December 29, 2022

First decision: January 30, 2023

Article in press: March 29, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jain V; Sintusek P, Thailand S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

Contributor Information

Inkyu S Lee, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Kenji Okumura, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States. kenji.okumura@wmchealth.org.

Ryosuke Misawa, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Hiroshi Sogawa, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Gregory Veillette, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Devon John, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Thomas Diflo, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Seigo Nishida, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Abhay Dhand, Department of Surgery, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States; Department of Medicine, Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY 10595, United States.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data reported here have been supplied by the UNOS as the contractor for the OPTN. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Cholankeril G, Podboy A, Alshuwaykh OS, Kim D, Kanwal F, Esquivel CO, Ahmed A. Early Impact of COVID-19 on Solid Organ Transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2020;104:2221–2224. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danziger-Isakov L, Blumberg EA, Manuel O, Sester M. Impact of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:925–937. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, Ebert BL, Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:565–567. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riera R, Bagattini ÂM, Pacheco RL, Pachito DV, Roitberg F, Ilbawi A. Delays and Disruptions in Cancer Health Care Due to COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:311–323. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okumura K, Nishida S, Sogawa H, Veillette GR, Bodin R, Wolf DC, Dhand A. Inferior Liver Transplant Outcomes during early COVID-19 pandemic in United States. J Liver Transpl . 2022;7:100099 – 100099. doi: 10.1016/j.liver.2022.100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394–1403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, Camerini T, Roayaie S, Schwartz ME, Grazi GL, Adam R, Neuhaus P, Salizzoni M, Bruix J, Forner A, De Carlis L, Cillo U, Burroughs AK, Troisi R, Rossi M, Gerunda GE, Lerut J, Belghiti J, Boin I, Gugenheim J, Rochling F, Van Hoek B, Majno P Metroticket Investigator Study Group. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewin SM, Mehta N, Kelley RK, Roberts JP, Yao FY, Brandman D. Liver transplantation recipients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis have lower risk hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:1015–1022. doi: 10.1002/lt.24764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, DebRoy MA, Greenstein SM, Merion RM. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fancellu A, Sanna V, Scognamillo F, Feo CF, Vidili G, Nigri G, Porcu A. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive review of current recommendations. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:3517–3530. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i15.3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inchingolo R, Acquafredda F, Tedeschi M, Laera L, Surico G, Surgo A, Fiorentino A, Spiliopoulos S, de'Angelis N, Memeo R. Worldwide management of hepatocellular carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:3780–3789. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandhi M, Ling WH, Chen CH, Lee JH, Kudo M, Chanwat R, Strasser SI, Xu Z, Lai SH, Chow PK. Impact of COVID-19 on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Management: A Multicountry and Region Study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021;8:1159–1167. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S329018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akbulut S, Garzali IU, Hargura AS, Aloun A, Yilmaz S. Screening, Surveillance, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Narrative Review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12029-022-00830-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarino M, Cossiga V, Capasso M, Mazzarelli C, Pelizzaro F, Sacco R, Russo FP, Vitale A, Trevisani F, Cabibbo G The Associazione Italiana Per Lo Studio Del Fegato AISF HCC Special Interest Group. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on the Management of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Med. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/jcm11154475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Alcoholic Liver Disease Replaces Hepatitis C Virus Infection as the Leading Indication for Liver Transplantation in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1356–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bittermann T, Mahmud N, Abt P. Trends in Liver Transplantation for Acute Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2118713. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cholankeril G, Goli K, Rana A, Hernaez R, Podboy A, Jalal P, Da BL, Satapathy SK, Kim D, Ahmed A, Goss J, Kanwal F. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Liver Transplantation and Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease in the USA. Hepatology. 2021;74:3316–3329. doi: 10.1002/hep.32067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandal S, Boyarsky BJ, Massie A, Chiang TP, Segev DL, Cantarovich M. Immunosuppression practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multinational survey study of transplant programs. Clin Transplant. 2021;35:e14376. doi: 10.1111/ctr.14376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straś WA, Wasiak D, Łągiewska B, Tronina O, Hreńczuk M, Gotlib J, Lisik W, Małkowski P. Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Liver Transplantation: Risk Factors and Predictive Models. Ann Transplant. 2022;27:e934924. doi: 10.12659/AOT.934924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.System notice: Liver and intestinal organ distribution based on acuity circles implemented Feb. 4 United Network for Organ Sharing 2022 Available from: https://unos.org/news/system-implementation-notice-liver-and-intestinal-organ-distribution-based-on-acuity-circles-implemented-feb-4/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data reported here have been supplied by the UNOS as the contractor for the OPTN. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the United States Government.