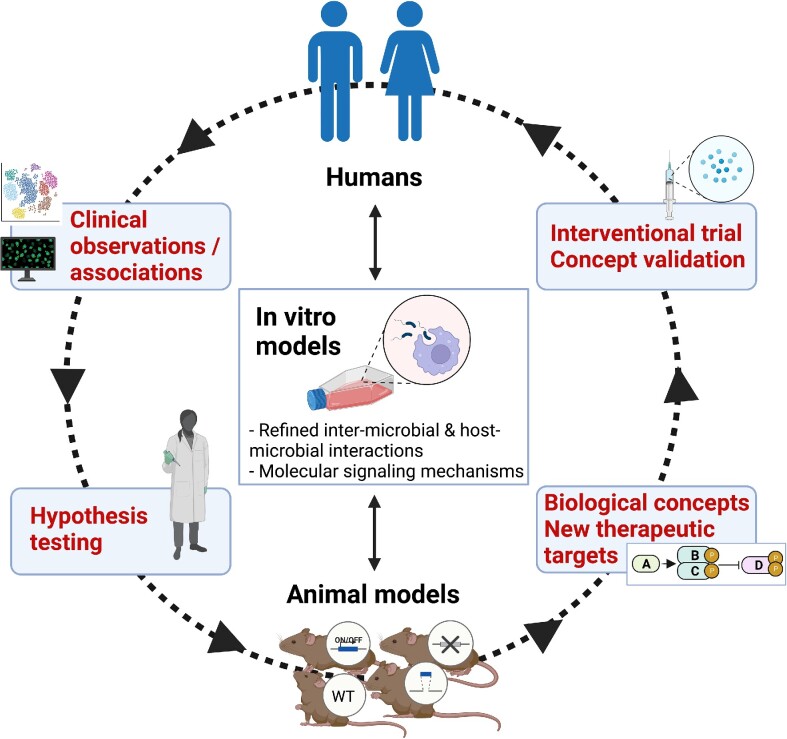

Figure 3.

Animal models are not used or interpreted in isolation. Work in model organisms informs and is being informed by clinical research and in vitro systems as indicated in this feed-forward cycle of knowledge generation. For instance, a clinical observation (e.g. protein “A” is negatively correlated with protein “D”) may prompt a hypothesis that can be tested in an animal model (often with the help of in vitro assays) leading to the conclusion that protein “A” activates a signaling pathway that inhibits protein “D.” If the inhibition of protein “D” in the animal model protects from a disease, then protein “D” can be identified as a candidate therapeutic target. This in turn can be tested for validation in an intervention trial, paving the way to clinical development for the treatment of human patients. One of the greatest contributions of experimental animals, especially mouse models with a plethora of knock-out, knock-in or conditional mutations, is the capacity for testing causality, which cannot be typically addressed in human studies that are mostly correlative.