Abstract

Introduction

Nephrotoxin exposure is significantly associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) development. A standardized list of nephrotoxic medications to surveil and their perceived nephrotoxic potential (NxP) does not exist for non-critically ill patients.

Objective

This study generated consensus on the nephrotoxic effect of 195 medications used in the non-intensive care setting.

Methods

Potentially nephrotoxic medications were identified through a comprehensive literature search, and 29 participants with nephrology or pharmacist expertise were identified. The primary outcome was NxP by consensus. Participants rated each drug on a scale of 0–3 (not nephrotoxic to definite nephrotoxicity). Group consensus was met if ≥ 75% of responses were one single rating or a combination of two consecutive ratings. If ≥ 50% of responses indicated “unknown” or not used in the non-intensive care setting, the medication was removed for consideration. Medications not meeting consensus for a given round were included in the subsequent round(s).

Results

A total of 191 medications were identified in the literature, with 4 medications added after the first round from participants’ recommendations. NxP index rating consensus after three rounds was: 14 (7.2%) no NxP in almost all situations (rating 0); 62 (31.8%) unlikely/possibly nephrotoxic (rating 0.5); 21 (10.8%) possibly nephrotoxic (rating 1); 49 (25.1%) possibly/probably nephrotoxic (rating 1.5); 2 (1.0%) probably nephrotoxic (rating 2); 8 (4.1%) probably/definite nephrotoxic (rating 2.5); 0 (0.0%) definitely nephrotoxic (rating 3); and 39 (20.0%) medications were removed from consideration.

Conclusions

NxP index rating provides clinical consensus on perceived nephrotoxic medications in the non-intensive care setting and homogeneity for future clinical evaluations and research.

Key Points

| Nephrotoxicity consensus ratings of medications used in the non-intensive care setting were generated. |

| Ten drugs were considered to have probable to probably/definite nephrotoxicity with routine use. |

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a commonly encountered complication with an increasing incidence that occurs in the presence of acute and chronic illnesses [1]. Approximately one in five adults and one in three children hospitalized with an acute illness will develop AKI [2]. Moreover, a consistent association has been demonstrated between AKI and an increased risk of poor long-term outcomes including mortality, progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD), and greater healthcare resource utilization [3–5].

The pathophysiology of AKI is often multifactorial and complex. One significant predictor of AKI development in both the inpatient and outpatient settings is nephrotoxin exposure. Drug-induced AKI (D-AKI) is increasingly being recognized as a relatively common adverse drug event in clinical practice, with approximately 30% of AKI cases being attributable to drugs [6, 7]. Given the rates of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality associated with AKI, early detection and prevention of these adverse events is imperative to improving AKI rates and outcomes [8]. Importantly, clinicians must understand the mechanisms of drug-induced nephrotoxicity and prioritize the safe prescribing of nephrotoxic drugs, monitor for potential nephrotoxicity, and be aware of both patient- and drug-specific risk factors, as well as the drug’s inherent nephrotoxic potential (NxP), to mitigate these events [9].

This call-to-action requires healthcare professionals to synthesize complex and evolving information about potentially nephrotoxic drugs for clinical practice and research [10]. Despite this need, there is a discrepancy in nephrotoxins cited in the literature and a paucity of epidemiological studies that focus on the likelihood or potential of medications to cause AKI. A modified Delphi method (a systematic approach to generate consensus) has become a recognized method to develop nephrotoxin lists, yet there is still discordance among medications included on the available lists [11–14]. Nevertheless, lists of perceived nephrotoxins developed through consensus between experienced clinicians and used for surveillance have led to reduced days of AKI, AKI severity, and AKI incidence in pediatric patients, proving the utility of this method in clinical practice and the standardization of research studies [12, 15].

A standardized list of nephrotoxins and associated NxP ratings is needed to prioritize nephrotoxin stewardship and ensure consistency in patient care and research [10]. Importantly, standardized lists of nephrotoxins and associated NxP ratings should be specific to clinical settings because of varying drug use and nephrotoxicity risk for different patient populations. However, these lists only exist for adult and pediatric critically ill patients [11, 12, 16]. Therefore, the aim of our study was to generate consensus using a modified Delphi method on the NxP index rating of 195 medications used in the non-intensive care setting.

Methods

Delphi Design and Clinician Panel

This study was approved as exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Articles that had previously curated lists of nephrotoxins were consolidated to create the list of nephrotoxins evaluated in this study [7, 11, 17–21]. Clinicians, specifically nephrologists who had a minimum of 5 years of experience or board certification and non-intensive care pharmacists who had 5 years of experience practicing in hospital pharmacy, were identified through the Caring for OutPatiEnts after AKI (COPE-AKI) investigator group and professional affiliations. Emails were utilized to invite clinicians to participate in the study and to distribute the de-identified web-based surveys [22]. A total of 29 clinicians (16 physicians and 13 pharmacists) from 15 different institutions were recruited on the basis of prior recommendations for panel size and heterogeneity [23]. A modified Delphi method was used to generate a consensus NxP index rating [23, 24]. The Delphi method is a structured technique that utilizes various rounds to develop group consensus [23]. Each round was considered complete when a minimum of 18 clinicians responded to the survey, with a minimum of nine pharmacists and nine physicians in each round. Given the survey was de-identified, all inputs were equally weighted to limit stature, seniority, or authority from influencing responses [25].

Delphi Rounds

For each round, participants were tasked to independently rank the NxP of each medication on the basis of clinical experience using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Causality Scale (0 for no NxP in almost all situations; 1 for NxP possible within routine use; 2 for NxP probable within routine use; 3 for NxP definite within routine use). In round one, clinicians were also able to provide further context to their responses, as well as suggest medications that they believed have NxP and were not included in the original 191 medications. Rounds two and three provided a summary of each medication’s previous rating. For the one medication that remained in round three, clinicians were also provided the summary rating for medications in the same drug class and a link to a repository containing an article that described the medication’s effect on kidney function.

Consensus Criteria

Consensus was predetermined as one of two scenarios: ≥ 75% agreement for one single rating of 0–3 or ≥ 75% agreement after combining two consecutive ratings. If consensus was obtained from the latter, the final rating was defined as falling between the two ratings. For example, out of 24 responses, a medication receiving 12 ratings of “1” and nine ratings of “2” received a final consensus rating of 1.5. Medications with ≥ 50% of responses indicating “unknown” or not used in the non-intensive care setting were removed.

Analysis

The Delphi process occurred between December 2021 and March 2022. A total of three rounds were completed. Consensus agreement was assessed after each round by aggregating participants’ scores. Medications that reached consensus were not included in subsequent rounds. All parameters from the previous round were carried forward for the following round unless described otherwise.

Results

Overall, 195 medications were evaluated (191 medications identified in the literature and 4 medications added after the first round from participants’ recommendations). The modified Delphi process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Modified Delphi method flowchart

In the first round, 170/191 medications reached consensus. Of these, 26 were those with ≥ 75% responses for one single rating, 102 reached ≥ 75% after combining two consecutive ratings, and 38 were medications with ≥ 50% indicating “unknown” or that the medication was not used outside the critical care setting. An additional 4 drugs were added for the second round, in addition to the remaining 21 medications from the previous round. Of the 25 medications evaluated in round two, 24 reached consensus, with 7 having ≥ 75% responses for one single rating, 16 having ≥ 75% after combining two consecutive ratings, and one medication as ≥ 50% indicating “unknown” or that the medication was not used outside the critical care setting. Only one medication remained for the third round, which reached a final consensus after having a ≥ 75% response for one single rating.

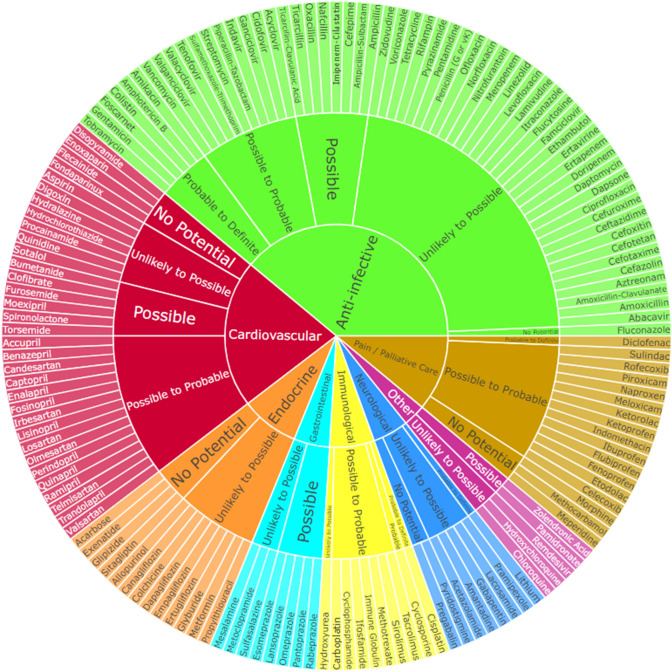

After three survey rounds, the NxP index rating consensus for routine drug use was: 14 (7.2%) no NxP in almost all situations (rating 0); 62 (31.8%) unlikely/possibly nephrotoxic (rating 0.5); 21 (10.8%) possibly nephrotoxic (rating 1); 49 (25.1%) possibly/probably nephrotoxic (rating 1.5); 2 (1.0%) probably nephrotoxic (rating 2); 8 (4.1%) probably/definite nephrotoxic (rating 2.5); 0 (0.0%) definitely nephrotoxic (rating 3); and 39 (20.0%) medications were removed. A summary of the NxP index ratings may be found in Table 1. Differences between physician and pharmacist consensus scores were seen for 44 medications (Table 2). Physicians reported higher nephrotoxicity ratings for 27 of the 44 medications. The difference in rating did not exceed one level on the scale, so (0–1, 1, 2) but not (0–2, 1–3). Figure 2 illustrates the NxP index ratings by drug class.

Table 1.

Consensus ratings of the nephrotoxic potential of 195 medications used in adults in the non-intensive care setting

| 0 (No NxP in almost all situations) | ||||||

| Acarbose | Disopyramide | Enoxaparin | Exenatide | Flecainide | Fluconazole | Fondaparinux |

| Glipizide | Meperidine | Methocarbamol | Morphine | Pregabalin | Pyridostigmine | Sitagliptin |

| 0.5 (NxP unlikely to possible within routine use) | ||||||

| Abacavir | Acetazolamide | Allopurinol | Amantadine | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid | Aspirin |

| Aztreonam | Canagliflozin | Cefazolin | Cefotaxime | Cefotetan | Cefoxitin | Ceftazidime |

| Cefuroxime | Chloroquine | Ciprofloxacin | Colchicine | Dapagliflozin | Dapsone | Daptomycin |

| Digoxin | Doripenem | Empagliflozin | Ertapenem | Ertugliflozin | Ethambutol | Etravirine |

| Famciclovir | Flucytosine | Gabapentin | Glyburide | Hydralazine | Hydrochlorothiazide | Hydroxychloroquine |

| Hydroxyurea | Itraconazole | Lacosamide | Lamivudine | Levofloxacin | Linezolid | Meropenem |

| Mesalamine | Metformin | Metoclopramide | Nitrofurantoin | Norfloxacin | Ofloxacin | Penicillin G/K |

| Pentamidine | Pramipexole | Procainamide | Propylthiouracil | Pyrazinamide | Quinidine | Remdesivir |

| Rifampin | Sotalol | Sulfasalazine | Tetracycline | Voriconazole | Zidovudine | |

| 1 (NxP possible within routine use) | ||||||

| Ampicillin | Ampicillin/sulbactam | Bumetanide | Cefepime | Clofibrate | Esomeprazole | Furosemide |

| Imipenem/cilastatin | Lansoprazole | Moexipril | Nafcillin | Omeprazole | Oxacillin | Pamidronate |

| Pantoprazole | Rabeprazole | Spironolactone | Ticarcillin | Ticarcillin/clavulanic acid | Torsemide | Zoledronic acid |

| 1.5 (NxP possible to probable within routine use) | ||||||

| Accupril | Acyclovir | Benazepril | Candesartan | Captopril | Carboplatin | Celecoxib |

| Cidofovir | Cyclophosphamide | Diclofenac | Enalapril | Etodolac | Fenoprofen | Flurbiprofen |

| Fosinopril | Ganciclovir | Ibuprofen | Ifosfamide | Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) | Indinavir | Indomethacin |

| Irbesartan | Ketoprofen | Ketorolac | Lisinopril | Losartan | Meloxicam | Methotrexate |

| Naproxen | Neomycin | Olmesartan | Perindopril | Piperacillin/tazobactam | Piroxicam | Quinapril |

| Ramipril | Rofecoxib | Sirolimus | Streptomycin | Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | Sulindac | Tacrolimus |

| Telmisartan | Tenofovir | Trandolapril | Valacyclovir | Valganciclovir | Valsartan | Vancomycin |

| 2 (NxP probable within routine use) | ||||||

| Colistimethate | Cyclosporine | |||||

| 2.5 (NxP probable to definite within routine use) | ||||||

| Amikacin | Amphotericin B | Cisplatin | Colistin | |||

| Foscarnet | Gentamicin | Lithium | Tobramycin | |||

| Unknown/not used outside the critical care setting | ||||||

| Acetohexamide | Adefovir | Atezolizumab | Bevacizumab | Capreomycin | Chlorpropamide | Cycloserine |

| Cytarabine | Didanosine | Diflunisal | Dofetilide | Doxacurium | Durvalumab | Eptifibatide |

| Etoposide | Fludarabine | Gallamine | Idarubicin | Imatinib | Ipilimumab | Lomustine |

| Melphalan | Metocurine | Mitomycin | Mivacurium | Nabumetone | Neostigmine | Nivolumab |

| Pancuronium | Pembrolizumab | Pemetrexed | Pentostatin | Pralatrexate | Stavudine | Temozolomide |

| Tocainide | Tolmetin | Topotecan | Trimetrexate | |||

Nephrotoxic potential was not evaluated on the basis of route of administration or high- versus low-dose therapy

Table 2.

Differences in physician and pharmacist nephrotoxicity ratings

| Medication | Physician rating | Pharmacist rating | Medication | Physician rating | Pharmacist rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetazolamide | 0 | 1 | Levofloxacin | 1 | 0 |

| Acyclovir | 2 | 3 | Lithium | 2 | 1 |

| Amphotericin B | 2 | 3 | Meloxicam | 2 | 1 |

| Aspirin | 1 | 0 | Methotrexate | 1 | 2 |

| Celecoxib | 2 | 1 | Nitrofurantoin | 1 | 0 |

| Chloroquine | 0 | 1 | Norfloxacin | 1 | 0 |

| Cidofovir | 1 | 2 | Ofloxacin | 1 | 0 |

| Colistin | 2 | 3 | Piroxicam | 2 | 1 |

| Dapsone | 1 | 0 | Procainamide | 1 | 0 |

| Daptomycin | 1 | 0 | Propylthiouracil | 1 | 0 |

| Etodolac | 3 | 2 | Quinidine | 1 | 0 |

| Famciclovir | 1 | 0 | Rifampin | 1 | 0 |

| Fenoprofen | 1 | 2 | Rofecoxib | 2 | 1 |

| Flurbiprofen | 1 | 2 | Sirolimus | 2 | 1 |

| Flucytosine | 1 | 2 | Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | 1 | 2 |

| Foscarnet | 2 | 3 | Sulfasalazine | 1 | 0 |

| Ganciclovir | 1 | 2 | Sulindac | 2 | 1 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | 3 | Tacrolimus | 3 | 2 |

| Hydralazine | 1 | 0 | Tenofovir | 2 | 1 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0 | 1 | Tetracycline | 1 | 0 |

| Itraconazole | 1 | 0 | Vancomycin | 1 | 2 |

| Ketoprofen | 1 | 2 | Voriconazole | 1 | 0 |

Ratings provided are the most commonly reported responses in each clinician group during the round the medication reached consensus. Excludes medications where the consensus rating was “unknown or not used in the non-intensive care setting” and medications where both clinician groups reported the same ratings. In the instance of a tie, the highest rating is provided

Fig. 2.

Consensus nephrotoxicity ratings by medication therapeutic class. Numeric ratings corresponding to each nephrotoxicity category are as follows: 0, no potential; 0.5, unlikely to possible; 1.0, possible; 1.5, possible to probable; 2.0, probable; 2.5, probable to definite; 3.0, definite (no medication received a 3 rating)

Discussion

A NxP index rating was determined by an interdisciplinary experienced group of non-intensive care clinicians for medications used in the non-intensive care setting. The generation of this list provides clinical consensus on nephrotoxic medications and assists in the prioritization of drugs with greater NxP for nephrotoxin stewardship programs [10]. The rank list additionally may serve as a vital tool to facilitate the development and implementation of clinical decision support systems that are highly predictive of AKI in both the hospital and community settings to mitigate the detrimental effects from cumulative nephrotoxic burden and can be used in future research and practice improvement initiatives [10]. Modifications to alert knowledge are needed to improve performance, minimize false positives and alert fatigue, and include contemporary AKI definitions and actionable nephrotoxin exposure data [26]. Importantly, this modified Delphi study provides consensus on NxP ratings that can guide surveillance in clinical practice.

In the continuum of care for kidney disease, clinicians should opt for fewer nephrotoxic drugs and/or avoid the use of a nephrotoxins. The odds of developing AKI is 1.5 times more likely for patients who receive a nephrotoxic medication and is compounded as patients receiving more than one nephrotoxin [18, 27]. In the non-intensive care setting, increasing nephrotoxin exposure and intensity from two to three medications nearly doubles the risk of developing AKI, and after receiving three or more nephrotoxins 25% of non-critically ill pediatric patients developed AKI [28, 29]. This concept of nephrotoxin intensity has commonly been referred to as nephrotoxic burden, which expands the concept to include the cumulative or aggregate exposure to nephrotoxins that factors in the NxP of each drug [10]. Ehrmann et al. used a similar approach, defining nephrotoxic burden on the basis of the days patients received a nephrotoxin. A significant association was seen between higher drug burden scores and AKI occurrence or worsening AKI for patients with lower severity of disease, however, the NxP of each medication was not accounted for in the burden assessment [30]. Knowledge of the NxP index rating is invaluable in the assessment of nephrotoxin exposure in non-critically ill patients and considers injury potential rather than equal weighting for nephrotoxic burden.

A multitude of methods have previously been employed to generate the NxP for various medications [11–13, 16, 31]. Welch et al. and Sileanu et al. determined the NxP on the basis of how often a drug was cited in the literature as being nephrotoxic. Medications were considered a “known” nephrotoxin if at least three out of four drug information sources listed the drug as nephrotoxic. A “possible” or “new potential” association was assigned if a drug was cited as a nephrotoxin in one to two references or none of the references, respectively [13, 31]. Other studies used a modified Delphi method in various patient populations and care settings to establish a NxP. Wang et al. ranked 62 nephrotoxins as moderate or high risk in a pediatric hospital. However, this was not the primary outcome of the study and minimal detail was provided as to how medications were classified [11]. Goswami et al. also focused on the pediatric population, generating a list of 57 nephrotoxins for surveillance within a collaborative group of pediatric hospitals. The investigators clearly outlined a process to develop and annually update a standardized nephrotoxin list to surveil in clinical practice [12]. Similarly, Gray et al. were transparent in the generation of NxP index ratings specific to adult critically ill patients, and the same methods were employed in our current study [16].

Despite using the same approach as Gray et al., there were several differences between our findings. Overall, only 7 drugs were ranked as probable or probable/definite nephrotoxicity with routine use in both studies, with different NxP index ratings observed for 14 other medications (Table 3). A higher NxP rating was assigned in the intensive care setting for 13 of the medications, with lithium being the only medication ranked higher in the non-intensive care setting. This is not surprising since patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are sicker and predisposed to a multitude of risk factors for AKI development, so the addition of a nephrotoxin could result in a compound effect, with even the smallest changes in serum creatinine being associated with a greater risk [32]. For example, vancomycin is often used in settings with increased risk of AKI, such as sepsis, and often in combination with other nephrotoxic medications, posing a risk of additive toxicities. Thus, there may be confounding in assessment of etiology of AKI, with uncertainty as to whether elevated vancomycin levels are the result of, rather than the cause of, AKI. The differences in reporting also reflect the experience and perception of clinicians in both settings. In general, clinicians in the outpatient and non-intensive care settings are more familiar with lithium compared with those in the ICU, as lithium nephrotoxicity is a slowly progressing disease that occurs over many years [33]. One drug that was ranked as probable in the current study that was not evaluated by Gray et al. was colistimethate. We hypothesize this was not included by Gray et al. due to colistin being more commonly used, however, colistimethate was included in our study to be more comprehensive. Importantly, we observed differences in NxP ratings between colistin and colistimethate (2.5 versus 2). Moreover, a greater number of medications were evaluated in the current study compared with the intensive care Delphi (195 versus 167 medications). These discrepancies are likely due to differences in utilization between care settings and drugs being removed due to the lack of use in either non-critically or critically care patients, respectively. This emphasizes the need for standardized lists of nephrotoxins to be population specific (AKI versus CKD, critically ill versus non-critically ill, children versus adults). Moreover, both studies saw physicians consistently ranked nephrotoxins as having a higher NxP index rating compared with pharmacists, suggesting physicians may be more cautious in considering the nephrotoxicity of medications. Again, this stresses the need for standardized NxP index ratings for consistent evaluation of medications in clinical practice and research.

Table 3.

Comparison of probable to probable/definite nephrotoxic potential in critical care adult modified Delphi study to the nephrotoxic potential in current non-intensive care adult modified Delphi study

| Nephrotoxin | Non-ICU nephrotoxic potential rating | ICU nephrotoxic potential rating |

|---|---|---|

| Agreement in rating between studies (n = 7) | ||

| Amikacin | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Amphotericin B | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Cisplatin | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Colistin | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Foscarnet | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Gentamicin | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Tobramycin | Probable/definite | Probable/definite |

| Discrepancy in rating between studies (n = 14) | ||

| Carboplatin | Possible/probable | Probably/definite |

| Cidofovir | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

| Cyclosporin | Probable | Probable/definite |

| Diclofenac | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

| Ibuprofen | Possible/probable | Probable |

| Indomethacin | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

| Ketoprofen | Possible/probable | Probable |

| Ketorolac | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

| Lithium | Probable/definite | Possible/probable |

| Methotrexate | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

| Naproxen | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

| Rofecoxib | Possible/probable | Probable |

| Tacrolimus | Possible/probable | Probable |

| Vancomycin | Possible/probable | Probable/definite |

Interestingly, we also saw disagreements in NxP ratings among drugs in the same drug class, as did Gray and colleagues. In both studies, remdesivir received a lower NxP index rating compared with tenofovir. Differences in ratings between tenofovir and adefovir, two medications with nearly identical structures and similar indications, were also observed [34]. Additionally, we saw discrepancies within the medication classes angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), in which moexipril was the only medication from the two classes to receive a NxP rating of 1 and the others received the rating of 1.5. Given these medications are in the same drug class and work via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway, we would expect these medications to receive the same NxP rating. This discrepancy may highlight reduced clinician familiarity with this medication and mirror the prescribing patterns in the outpatient setting, where medications such as lisinopril and valsartan are being used more frequently compared with moexipril. Further investigation is required to assess these deviations in NxP index ratings among drugs within a drug class. In addition, epidemiological studies using large real-world data are needed to validate the NxP index ratings generated in this study.

A Delphi is intended to obtain clinician opinion, so the inclusion of a comprehensive list of medications allowed us to gain insight on perception. Still, the selection of appropriate medications to surveil is imperative, and controversies may arise regarding the medications included for NxP evaluation. For example, medications that work via the RAAS pathway are considered renoprotective and not inherently nephrotoxic. We developed a comprehensive list on the basis of the literature, and these drugs have been included in previous studies. However, we must consider both structural and functional changes to the kidney that can result in D-AKI [35]. In the setting of reduced renal perfusion (i.e., bilateral renal artery stenosis, severe hypotension, severe intrarenal arteriosclerosis, etc.) the threshold for injury or worsening of kidney injury is lowered, possibly leading to damage in contextual situations [36]. Consequently, ACEi and ARBs contribute to a decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) via inhibiting vasoconstriction of the efferent arteriole. This effect on intrarenal hemodynamics can result in an increase in serum creatinine without structural damage. Comparably, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors further decrease GFR via inhibiting vasodilatation of the afferent arteriole. In a conventional medical unit, AKI was predominately due to functional etiologies, with approximately 20% of cases being due to dehydration associated with drug-induced renal hypoperfusion (i.e., ACEi, ARBs, diuretics, or NSAIDs) [37]. Structural etiologies of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and glomerular disease represented 16–22% and 7–14% of AKI cases, respectively. Nonetheless, nephrotoxic stewardship strategies should target medications with the potential to result in injury and consider patient- and drug-specific risk factors to mitigate these events.

Limitations

A consensus NxP index rating was generated for medications used in the non-intensive care setting using a modified Delphi method. The use of a modified Delphi technique enabled there to be flexibility in generating consensus using a standardized definition, and participants were able to provide feedback after the first round. We attempted to generate a comprehensive list of medications to evaluate via combining previously defined lists of nephrotoxins, but it is possible some medications were missed, as exhibited with the addition of four medications after round one on the basis of participant feedback. Some other drugs worth considering in future studies may include aliskiren, gemcitabine, sorafenib, sunitinib, azacytidine, streptozocin, everolimus, lenalidomide, deferasirox, acetaminophen, phenytoin, and histamine H2-receptor antagonists. A medication worth clarifying would be the specific forms of tenofovir, as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is more nephrotoxic compared with its counterpart tenofovir alafenamide, and this delineation was not made in the survey [38]. Moreover, the nephrotoxicity potential of medications was not evaluated on the basis of routes of administration or a dose-dependent effect. This may be clinically important for medications such as amphotericin B and methotrexate and should be considered for future studies.

Further divergences may arise from this list on the basis of the patient population or due to being excluded because of lack of perceived use in the non-intensive care setting. Many of the potential nephrotoxins considered chemotherapeutics are unknown, suggesting a lack of experience with these drugs. However, it is possible these medications are not commonly seen in the non-intensive care setting but rather used in outpatient infusion centers. Study participants were asked to rank the perceived NxP on the basis of general use in a non-intensive care setting, but patient- and environment-specific factors may alter the nephrotoxicity of medications, which could limit the generalizability of our results. Moreover, the definition of nephrotoxicity was not provided to the clinicians since there is no definition of agreement to use and is subject to opinion. Because of this, the definition of nephrotoxicity was subject to interpretation by the expert clinicians. Furthermore, our study only included clinicians who practiced in the USA, which may limit the use of our list in our countries pending the utility of these medications in practice. Because the NxP index rating was determined on the basis of consensus agreement and relies on perception and experience, newer drugs that lack familiarity may result in a lower rating. As new drugs and new medication safety data on old medications become available, the rank list will need to be updated. Further epidemiological association studies are necessary to validate the NxP index ratings generated via a modified Delphi method.

Conclusions

Ten drugs were considered to have probable to probably/definite nephrotoxicity by a group of clinicians with experience in nephrology and adult non-intensive care. This NxP index rating provides clinical consensus on perceived nephrotoxic medications and homogeneity for future clinical evaluations. Moreover, the rank list assists in the prioritization of drugs with greater NxP for nephrotoxin stewardship programs in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This work has previously been presented in the form of an abstract presentation at the 2022 ACCP Virtual Poster Symposium.

Declarations

Disclosures

Ivonne H. Schulman contributed to this manuscript in her personal capacity. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

Funding

This study was funded by U01DK130010.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KZA has received support from AKI grant U01DK130010. LF has served as a consultant for Bayer and is a member of the DSMB for Novo Nordisk and CSL Behring. ES serves on the Editorial Board of CJASN and has received royalties as an author for UpToDate. FPW has received support from AKI grants R01DK113191, P30DK079310, and R01HS027626. MRW has served as a scientific advisor for Bayer, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, and Novo Nordisk. SKG has received support from AKI grants U01DK130010 and R01DK121730-01. Authors BAS, PMP, IHS, CRP, EP, OMG, EH declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was reviewed by the University of Pittsburgh International Review Board (STUDY21070204) and designated as exempt for minimal risk before study commencement.

Consent to Participate

Recruitment materials explained that completion of the survey constituted consent to have the respondent’s de-identified results included in the study, but that the respondent could opt out at any time.

Consent for Publication

Recruitment materials explained that completion of the survey constituted consent to have the respondent’s anonymous results included in the study, but that the respondent could opt out at any time.

Data Availability

Available upon request to the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

BS was responsible for concept generation, materials creation, ethics approval, data analysis, manuscript drafting, and revision; KA for concept generation, material review, and manuscript review; PMP for concept generation, material review, manuscript review. LF: concept generation, material review, manuscript review; IS, CP, EP, ES, JF, OMG, EH, MW, and FPW for concept generation and manuscript review; and SKG for concept generation and material review and distribution, manuscript drafting, and revision. All authors read and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Levey A, James M. Acute kidney injury. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(9):ITC66–ITC80. doi: 10.7326/AITC201711070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, et al. World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(9):1482–1493. doi: 10.2215/cjn.00710113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Statistical brief #231: acute renal failure hospitalizations, 2005–2014 (2017).

- 4.USRDS 2016 annual data report: an overview of the epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States (2016).

- 5.Lameire N, Bagga A, Cruz D, et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet. 2013;382(9887):170–179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirali A, Pazhayattil GS. Drug-induced impairment of renal function. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:457–468. doi: 10.2147/ijnrd.s39747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta R, Awdishu L, Davenport A, Murray P, Macedo E, Cerda J. Phenotype standardization for drug-induced kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88(2):226–234. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(3):844–861. doi: 10.2215/cjn.05191107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GhaneShahrbaf F, Assadi F. Drug-induced renal disorders. J Renal Inj Prev. 2015;4(3):57–60. doi: 10.12861/jrip.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane-Gill SL. Nephrotoxin stewardship. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37:303–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, McGregor T, Jones D. Electronic health record-based predictive models for acute kidney injury screening in pediatric inpatients. Pediatr Res. 2017;82(3):465–473. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goswami E, Ogden RK, Bennett WE, et al. Evidence-based development of a nephrotoxic medication list to screen for acute kidney injury risk in hospitalized children. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(22):1869–1874. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxz203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sileanu FE, Murugan R, Lucko N, et al. AKI in low-risk versus high-risk patients in intensive care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):187–196. doi: 10.2215/cjn.03200314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares D, Mambrini J, Botelho G, Girundi F, Botoni F, Martins M. Drug therapy and other factors associated with the development of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a cross-sectional study. Peer J. 2018;6:e5405. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein S, Dahale D, Kirkendall E, Mottes T, Kaplan H, et al. A prospective multi-center quality improvement initiative (NINJA) indicates a reduction in nephrotoxic acute kidney injury in hospitalized children. Kidney Int. 2020;97(3):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray MP, Barreto EF, Schreier DJ, et al. Consensus obtained for the nephrotoxic potential of 167 drugs in adult critically ill patients using a modified Delphi method. Drug Saf. 2022;45(4):389–398. doi: 10.1007/s40264-022-01173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox Z, McCoy A, Matheny M, Bhave G, Peterson N, Siew E. Adverse drug events during AKI and its recovery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(7):1070–1078. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11921112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivosecchi R, Kellum J, Dasta J, Armahizer M, Bolesta S, Buckley M. Drug class combination-associated acute kidney injury. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(11):953–972. doi: 10.1177/1060028016657839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panel BtAGSBCUE American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanlon J, Aspinall S, Semla T. Consensus guidelines for oral dosing of primarily renally cleared medications in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(2):335–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taji L, Battistella M, Grill A. Medications used routinely in primary care to be dose-adjusted or avoided in people with chronic kidney disease: results of a modified Delphi study. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54(7):625–632. doi: 10.1177/1060028019897371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com. Accessed March 16, 2022

- 23.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(4):376–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helmer-Hirschberg O. Analysis of the future: the Delphi method. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane-Gill S, O'Connor M, Rothschild J, Selby N, McLean B, Bonafide C. Technologic distractions (part 1): summary of approaches to manage alert quantity with intent to reduce alert fatigue and suggestions for alert fatigue metrics. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):1481–1488. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cartin-Ceba R, Kashiouris M, Plataki M, Kor DJ, Gajic O, Casey ET. Risk factors for development of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2012/691013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein SL, Jaber BL, Faubel S, Chawla LS. AKI transition of care: a potential opportunity to detect and prevent CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(3):476–483. doi: 10.2215/cjn.12101112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moffett BS, Goldstein SL. Acute kidney injury and increasing nephrotoxic-medication exposure in noncritically-ill children. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(4):856–863. doi: 10.2215/cjn.08110910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehrmann S, Helms J, Joret A, et al. Nephrotoxic drug burden among 1001 critically ill patients: impact on acute kidney injury. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0580-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welch HK, Kellum JA, Kane-Gill SL. Drug-associated acute kidney injury identified in the United States Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system database. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(8):785–793. doi: 10.1002/phar.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singbartl K, Kellum JA. AKI in the ICU: definition, epidemiology, risk stratification, and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2012;81(9):819–825. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis J, Desmond M, Berk M. Lithium and nephrotoxicity: a literature review of approaches to clinical management and risk stratification. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):305. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-1101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Bömmel F, Wünsche T, Mauss S, et al. Comparison of adefovir and tenofovir in the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;40(6):1421–1425. doi: 10.1002/hep.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makris K, Spanou L. Acute kidney injury: definition, pathophysiology and clinical phenotypes. Clin Biochem Rev. 2016;37(2):85–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abuelo JG. Normotensive ischemic acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra064398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bamoulid J, Philippot H, Kazory A, Yannaraki M, Crepin T, et al. Acute kidney injury in non-critical care setting: elaboration and validation of an in-hospital death prognosis score. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):419. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1610-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta SK, Post FA, Arribas JR, Eron JJ, Jr, Wohl DA, et al. Renal safety of tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: a pooled analysis of 26 clinical trials. AIDS. 2019;33(9):1455–1465. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request to the corresponding author.