Abstract

This study assesses whether prior marital quality moderates the impact of divorce or widowhood on subsequent depression. Poor marital quality may buffer depression associated with divorce/widowhood; conversely, the effect of divorce/widowhood on depression could be exacerbated by previous marital quality. Three waves from the National Survey of Families and Households based on respondents, ages 50 and older, (N = 2,570) included eight marital quality measures. We find limited evidence suggesting higher marital quality elevates, while lower marital quality decreases, depression after divorce. No moderating effects were found for widowhood. Additionally, health condition is more important than current marital status for elders’ well-being after divorce or widowhood. Heterogeneity in the context of the marriage before divorce should be considered when examining marital termination effects on elders’ depression.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, divorce, marital quality, older adults, widowhood

Although accumulated research has found a negative effect of marital termination on individuals’ well-being (Das, 2013; Metsä-Simola & Martikainen, 2013; Utz, Caserta, & Lund, 2011), according to life course theories (Dannefer, 2008; Elder, 1994), the time and place of such transitional events (i.e., divorce or widowhood) can also affect their influence on individuals’ well-being. As emphasized by Elder (1994, p. 12), “The developmental antecedents and consequences of life transitions, events, and behavioral patterns vary according to their timing in a person’s life.”

Compared with the loss of a spouse by widowhood, divorce is more unexpected for older adults. Although divorce rate among older adults has been increasing in the last decades because of the baby boom generation enters older age, Brown and Lin (2012) pointed out that divorce is still more common among middle-aged people than older adults. Using an Irish longitudinal data, Kamiya, Doyle, Henretta, & Timonen (2013) pointed out that divorce in later life had a direct impact on depressive symptoms. According to national longitudinal data, Lin (2008) showed that divorced elderly fathers have less financial support from their adult children than bereaved fathers (Lin, 2008).

In the meantime, because divorce has become more common than for past generations (Bowen & Jensen, 2015; Cherlin, 2010), divorce in later life may bring about fewer challenges for elders than for their predecessors. Since the population of single older adults has increased in the past decades, research on widowhood and divorce has become important to both policymakers and the general public.

Moreover, no consistent conclusions regarding the role of marital quality in moderating the impact of marital termination on subsequent well-being have been reached. Some studies found that experiencing a problematic marriage reduces distress or grief after divorce or widowhood (Amato & Hohmann-Marriott, 2007; Carr et al., 2000; Symoens, Colman, & Bracke, 2014). Others have found evidence to suggest that having low marital quality actually increases depressive symptoms upon marital transitions (Booth & Hawkins, 2005; Kalmijn & Monden, 2006). Many such studies are limited, however, by small sample sizes or do not include both divorce and widowhood in their analyses. The effect of different dimensions of marital quality as a moderator remains obscured because these studies only used simple measurement. As a result, the role of marital quality in the trajectory of psychological well-being after divorce/widowhood is still not well understood.

An understanding of the effect of previous marital quality on the relationship between marital termination and depressive symptomatology among older adults is critical for several reasons. First, the population of single older adults has increased in recent decades, largely due to divorce (Brown & Lin, 2012; Lin & Brown, 2012). Although widowhood has been a relatively common occurrence in this population, the ever-expanding numbers of elder divorcees is a relatively new phenomenon. How they adapt psychologically, therefore, is important for clinicians and policymakers to understand (Cherlin, 2010). Second, understanding how marital quality might condition reactions to negative events such as marital termination is critical to building family theory (Carr, 2004). Third, given the aging of the population, there is a need for a better understanding of how the family context in which such individuals are aging may affect their quality of life (Cherlin, 2010; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010).

In the current study, we examine how marital quality conditions the psychological ramifications of divorce or widowhood among older individuals. In particular, we test opposing hypotheses, regarding the buffering vs. exacerbating effects of poor marital quality in the marital termination-depression association. In the process, our study enhances knowledge of family processes and draws attention to the role of marital quality in later-life marital transitions and their influence on psychological well-being.

Prior marital quality and depressive symptoms

To date, studies have come to no consistent conclusion regarding the relationship between prior marital quality and personal well-being after widowhood or divorce. Some studies found that if a marriage provides intimate bonds and a sense of security, individuals will experience distress upon marital termination (Kamiya et al., 2013). After losing a partner, either through divorce or death, finding another partner is often a difficult endeavor. The latest study on remarriage in later life found out that 76.1% of women and 75% of men who divorced in their later life were unpartnered; 94% of women and 75% of men who widowed in their later life remained single (Brown, Lin, Hammersmith, & Wright, 2016). Lacking an intimate partner in one’s life is positively associated with depression. This should obtain even if a divorce is deliberately sought by both partners. Kamiya et al. (2013) found out that both divorce and widowhood are directly associated with depression. Carr et al. (2000) found that greater marital closeness before widowhood was associated with higher levels of negative feelings after being widowed.

However, ending a marriage can also be viewed as the beginning of a new life. For example, divorce can be a self-protective action that people can take to assist in getting away from a toxic relationship. Marital termination in such cases could be considered a solution instead of a problem. Mirowsky (2013) pointed out that unhappily married couples would often think of divorce. In Diaz, Molina, MacMillan, Duran, and Swart’s (2013) study, most of the respondents perceived divorce as a solution to unhappy marriage. Amato and Hohmann-Marriott (2007) found that divorced individuals who reported high-stress marriages, compared with those in low-stress marriages, reported an increase in happiness after divorce. Similar improvement in psychological well-being after having divorce from an unhappy marriage was also revealed in Waite, Luo, and Lewin’s (2009)’s study. Carr et al. (2000) and Wheaton (1990) also found that experiencing a conflictual marriage decreased the level of grief after becoming widowed. Our first hypothesis is, therefore,

H1: Lower marital quality weakens the damaging effect of marital termination on depressive symptomatology.

On the other hand, the loss of a marriage might result in an increase in depressive symptoms. For example, individuals may be reluctant to admit that they have unsatisfying marriages, postpone exiting from such relationships, and continue to “invest” in them in hopes of a future “recovery” (Ackert, Church, & Deaves, 2003; Fogel & Berry, 2006). By the time individuals’ marriages are terminated, it is possible that their investment in the relationship was too extensive for them to enjoy the escape from the situation.

In a similar vein, previous trauma may influence a person’s life even after the person has left the stressful environment (Freud, 1959). Therefore, individuals who terminate a marriage would experience distress even if their marital quality had been poor. For example, individuals may have treated their ex-spouses poorly. After the relationship ends, they are likely to experience guilt over the mishandling of their partner. A recent study on divorced people found out that divorcees would feel guilty for not working hard enough to save their marriages or not looking for help when marital crises came (Kiiski, Maatta, & Uusiautti, 2013). Guilt is associated with moral self-condemnation, such that individuals would seek forgiveness to avoid feeling immoral (Gecas, 1989). Lacking such forgiveness, they may experience depression. With the event of widowhood, survivors who have mistreated a former spouse have no opportunity to redeem themselves, which may also increase depression. Considering the foregoing, we tender a second, contrary hypothesis:

H2: lower marital quality strengthens the damaging effect of marital termination on depressive symptomatology.

Method

Data

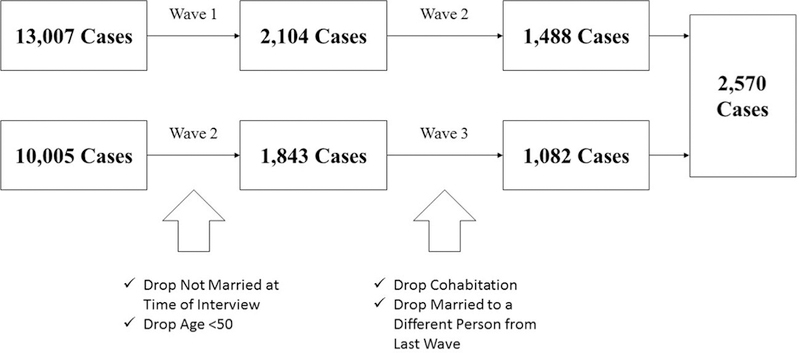

The National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) is based on a face-to-face original national probability sample of US households. Wave I was undertaken in 1987 and 1988 (N = 13,007). Wave II resurveyed 10,005 of the original respondents in 1992–1994. Wave III (N = 4,600), gathered in 2001 and 2002, recontacted select groups from the original respondents of Wave I who were 45 and older by January 1, 2001 and those who had at least one child. The present study was based on a two-period specification of the data. All respondents who were at least 50 years of age and married in the initial (1987 and 1988) survey were selected. In the Wave II follow-up, it was determined whether they were still married, divorced, or widowed. If their marriage was disrupted, and they were not currently cohabiting or remarried, they were coded as either divorced or widowed, depending on which circumstance terminated their marriage.

Our intent was to compare the currently widowed and divorced with those who were continuously married across waves. Therefore, those with marital terminations who were subsequently cohabiting or remarried at the follow-up were dropped from the study. If they were still married to the Wave I (1987 and 1988) partner at Wave II (1992–1994), they were followed to Wave III (2001 and 2002) of the survey, with their marital quality taken from the Wave II measurements. Additionally, any Wave I respondents reaching 50 years of age and currently married in Wave II were added to the sample. Hence, all cases currently married and aged 50 or older at Wave II were written out as “new” cases to the data set, with Wave II counting as “time 1” and Wave III counting as “time 2.” Once again, respondents whose marriage was disrupted between Waves II and III who were remarried or currently cohabiting in Wave III were dropped from the study. The entire sample is structured as a two-period data. Time 1 contained information of marital quality when all respondents were married. The marital quality in time 1 would help to predict the depressive symptoms in time 2 after considering the transition of marital status between time 1 and time 2.

There were 2,104 respondents who were married and at least 50 years old in Wave I. Because of cohabitation or being married to a different person, 616 cases were dropped in Wave II. There were 1,843 respondents who were married and at least 50 years old in Wave II, and 761 of these were dropped in Wave III because they were either cohabiting with or married to a different partner. Hence, there are 1,488 cases in the period from Waves I to II and 1,082 cases in the period from Waves II to III. Figure 1 depicts the sampling strategy for the current analyses. The total sample size was 2,570, with 368 persons who were widowed and 73 persons who divorced during the survey.

Figure 1.

Sample analysis strategy.

Measurement

Depressive symptomatology, the outcome variable, was measured at both times 1 and 2 using the 12-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). Respondents were asked how many days in the previous week they felt or experienced each of the following items: 1) lonely, 2) fearful, 3) depressed, 4) sad, 5) bothered by things that usually do not bother them, 6) felt like not eating, 7) unable to shake off the blues, 8) had trouble concentrating, 9) felt everything was an effort, 10) slept restlessly, 11) talked less than usual, and 12) were unable to get going. Each item was coded 0–7, and all 12 items were summed to create the scale. The scale ranged from 0 to 84, with 84 reflecting maximum depressive symptomatology. For a valid scale score, respondents had to have answered at least 50% of the items in the scale. Alpha reliability for the scale was .94 in Wave I, .96 in Wave II, and .90 in Wave III.

Marital status was composed of two dichotomous variables: one for those who were widowed at time 2, and one for those who divorced at time 2. Those who were still married to the same person at time 2 were treated as the reference group.

The construct of marital quality was assessed with eight questions (Choi & Marks, 2008; DeMaris, 2000, 2007; Waite, Luo, & Lewin, 2009). Marital happiness was assessed with the following statement: “Taking all things together, how would you describe your relationship”? Responses were scored on a seven-point scale (from 1 = “very unhappy” to 7 = “very happy”). The score was then centered for ease of interpretation in moderator analyses. Those who scored 0 on the marital happiness scale were those with an average level of marital happiness at that time.

Overbenefitting and underbenefitting referred to whether respondents felt that their relationships were fair in the following four domains: household chores, working for pay, spending money, and childcare. The answers were measured with a five-point scale: 1 = “very unfair to me”; 2 = “somewhat unfair to me”; 3 = “fair to both”; 4 = “somewhat unfair to the partner”; and 5 = “very unfair to the partner.” To create the overbenefit scale, each answer was recoded into a three-point scale from 0 (no overbenefit) to 2 (high overbenefit). Any score less than 4 on each fairness item was recoded as 0. Those who answered 4 were recoded as 1, and those who answered 5 were recoded as 2. The overbenefit items were then summed as a single scale. The higher the score, the more the respondent felt that he or she overbenefited in the marriage. For underbenefit, any score higher than 2 on each fairness item was coded as 0. Those who answered 2 were given 1 point of underbenefit on each item, and those who answered 1 were given 2 points. The underbenefit items were similarly summed into a single scale. The higher the score, the more the respondent felt that he or she underbenefited in the marriage. The alpha reliability for the underbenefit scale was .76 in Wave 1 and .67 in Wave 2. The alpha reliability for the overbenefit scale was .64 in Wave 1 and .71 in Wave 2. We considered these scales to be valid for everyone who answered at least 50% of the respective items.

Time spent together was measured by: “During the past month, about how often did you and your partner spend time alone with each other, talking, or sharing an activity?” Responses were coded as: 1 = “never,” 2 = “less than once a month,” 3 = “several times a month,” 4 = “about once a week,” 5 = “several times a week,” and 6 = “almost every day.” The score was then centered. The frequency of sex was measured by how often the respondent had sex during the past month. To avoid extremely unrealistic answers (i.e., 90 times in the past month), top coding was used to recode any value that was more than 30 times to 30.

Disagreement in the marriage was measured by asking how often during the last year the respondents and their spouses had disagreements on household tasks, money, spending time together, sex, in-laws, and childcare. Responses were measured using a six-point scale (1 = “never,” 2 = “less than once a month,” 3 = “several times a month,” 4 = “about once a week,” 5 = “several times a week,” and 6 = “almost every day”). The scale score was the sum of the items. The total score ranged from 6 to 36, and higher scores indicated more disagreements experienced in the marriage. The score was then centered to facilitate interpretation in interaction models. The alpha reliability for the scale was .99 in Wave 1 and .98 in Wave 2. Respondents had to have answered at least 50% of the items to get a valid score. Marital verbal aggression was measured by how often (0 = “never” and 4 = “always”) respondents argued heatedly or shouted at each other during the last year. Marital trouble was based on two questions: whether the respondents thought that their marriage was in trouble during the past year and whether the respondents thought their marriage “is in trouble now.” Marital trouble was coded as 1 if either or both of the answers were yes and 0 if the respondents answered no to both items.

The control variables in the study were household annual income and self-reported health, which previous research suggests may be associated with depressive symptoms. For example, marital termination usually causes a reduction in personal income; moreover, a decrease in income can increase individuals’ depression (Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006). Household annual income was measured at both times 1 and 2 in hundred thousands of dollars. Self-reported health scores were measured using the question: “Compared with other individuals your age, how would you describe your health?” Because the NSFH changed the scale from a five-point scale (from 1 = “very poor” to 5 = “excellent”) in Wave I to a seven-point scale (from 1 = “very poor” to 7 = “excellent”) in both Waves II and III, health scores were converted to standard scores based on the mean and standard deviation of the variable in the relevant waves. The main respondents’ self-reported health scores were obtained at both times 1 and 2.

Since the fixed effect model does not include time-invariant variables (i.e., race, gender, or education), these demographic features are not in the model. However, one of the advantages of using the fixed effect model is that this technique can control for time-invariant variables as well as unobserved variables.

Analytical strategy

We first report means and standard deviations for the whole sample and use ANOVA to test for the differences in study variables by marital status. We then use fixed effect regression modeling to assess the impact of marital transitions on depression across waves of the survey. The change in the response from time 1 to 2 is regressed on the changes in predictor variables from time 1 to 2, with marital status changes captured by time-varying dummy variables. Missing values on the response or the predictors were handled through listwise deletion. According to Allison (2002), listwise deletion is the missing-data strategy that is most robust to violation of the missing-at-random assumption for the independent variables. For the modeling sequence, we first tested the main effect of marital status on depressive symptoms. Then we added income and health as control variables to test whether the main effect of marital status remained significant. In subsequent models (Models 1–8 in the interaction effects table), we included the individual marital quality measures as moderators and tested the interaction effects separately in each model.

Results

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for all study variables. The average age of respondents was 61. The ANOVA F test shows whether these variables differ by marital status (still married, divorced, or widowed). Those who were still married at time 2 had the lowest time 1 depression. Divorced individuals had the highest time 1 depression among the three groups, followed by widowed individuals. Divorced individuals evinced the greatest level of underbenefit at time 1; however, there was no difference on overbenefit among the three groups. In terms of the amount of time spent together during their previous marriages, divorced individuals spent the least amount of time together. Widowed respondents had the lowest frequency of sex at time 1. Divorced respondents had the highest level of marital disagreement at time 1, followed by still married and widowed individuals. Divorced respondents also had the highest level of verbal aggression among the three groups. Divorced respondents had the highest probability of believing that their marriage was in trouble, while widowed respondents had the lowest probability of such thoughts among the three groups.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables by marital status at time 2.

| Variable | Total | Still married | Widowed | Divorced | ANOVA F | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

|

N = 2,570 |

N = 2,129 |

N = 368 |

N = 73 |

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Depression 1 | 11.24 | 14.88 | 10.41 | 13.86 | 15.08 | 18.78 | 16.14 | 17.77 | 19.26*** |

| Depression2 | 12.25 | 15.05 | 11.13 | 14.04 | 17.82 | 18.17 | 16.47 | 18.63 | 34.36*** |

| Age | 61.14 | 7.96 | 60.54 | 7.76 | 65.39 | 7.82 | 57.37 | 7.53 | 70.34*** |

| Marital happiness* | 6.06 | 1.34 | 6.10 | 1.30 | 6.07 | 1.30 | 4.77 | 1.98 | 32.45*** |

| Underbenefit | .44 | 1.16 | .41 | 1.11 | .58 | 1.32 | .72 | 1.62 | 5.40* |

| Overbenefit | .25 | .82 | .26 | .84 | .19 | .74 | .33 | .71 | 1.45 |

| Time together | 5.34 | 1.22 | 5.37 | 1.15 | 5.40 | 1.33 | 4.03 | 1.89 | 42.29*** |

| Sex frequency | 3.46 | 4.19 | 3.69 | 4.23 | 2.15 | 3.59 | 3.39 | 4.58 | 16.16*** |

| Disagreement* | 9.72 | 4.20 | 9.75 | 4.19 | 9.12 | 3.92 | 11.92 | 5.10 | 12.40*** |

| Verbal aggression | 1.74 | .88 | 1.73 | .87 | 1.74 | .92 | 2.01 | 1.12 | 3.76* |

| Marital trouble | .11 | .32 | .11 | .31 | .09 | .29 | .40 | .49 | 30.76*** |

| Income 1 | .00 | 1.00 | .04 | 1.07 | −.22 | .57 | −.09 | .44 | 9.82** |

| Income 2 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | .85 | −.03 | 1.42 | .24 | 2.03 | 2.31+ |

| Health 1 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | .99 | .01 | 1.07 | −.04 | .98 | .08 |

| Health 2 | .00 | 1.00 | .02 | .99 | −.10 | 1.04 | −.17 | 1.03 | 1.19 |

p ≤ .1,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Marital happiness and disagreement are not centered in this table. The centered variables are used in the fixed effect model.

Table 2 shows the results of fixed effect models of depressive symptoms, based on marital transition status and the other predictors. In Model 1, widowhood is positively associated with the level of depressive symptoms. However, divorced status appears to make no difference, compared with still married individuals. Time also shows a positive effect, though it is only marginally significant. After controlling for health and income, Model 2 shows that the effect of widowhood is no longer significant, compared with still married individuals. The effect of time is not significant either. On the other hand, health is significantly and negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Fixed effect models of depression (main effects).

| M1 |

M2 |

|

|---|---|---|

| B | B | |

|

| ||

| Divorced | −.11 | −1.96 |

| Widowed | 1.91* | 1.58 |

| Time | .69+ | .60 |

| Income | −.01 | |

| Health | −1.26*** | |

| R 2 | .71 | .77 |

p ≤ .1

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Table 3 presents the moderating effects of marital quality in the relationship between marital status and depressive symptoms. Model 1 reveals a significant interaction between marital happiness and marital transition status in their effects on depression. The happier the previous marriage had, the more depression the divorcees were. In addition, health is still significant and negatively associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Fixed effect models of depression including interactions of marital status with marital quality indices.

| M1 B |

M2 B |

M3 B |

M4 B |

M5 B |

M6 B |

M7 B |

M8 B |

|

|

| ||||||||

| Divorced | 2.32 | −.49 | −.84 | −.53 | −1.94 | .60 | −1.79 | 4.91 + |

| Widowed | 1.46 | 1.44 | 2.05+ | 1.69+ | 2.65* | 2.00* | 1.58 | 1.62 |

| Time | .63 | .61 | .65+ | .63 | .30 | .49 | .59 | .59 |

| Income | −.21 | −.03 | −.03 | −.04 | −.05 | −.11 | −.02 | −.03 |

| Health | −1.21*** | −1.26*** | −1.25*** | −1.19*** | −1.39*** | −1.27*** | −1.26*** | −1.26*** |

| Divorced* Marital happinessc | 2.33* | |||||||

| Widowed*Marital happinessc | −.49 | |||||||

| Divorced*Underbenefit | −1.05 | |||||||

| Widowed*Underbenefit | .50 | |||||||

| Divorced*Overbenefit | .13 | |||||||

| Widowed*Overbenefit | −1.36 | |||||||

| Divorced*Time spendingc | 1.23 | |||||||

| Widowed*Time spendingc | −.57 | |||||||

| Divorced*Sex frequency | .28 | |||||||

| Widowed*Sex frequency | −.09 | |||||||

| Divorced*Marital disagreementc | −.70+ | |||||||

| Widowed*Marital disagreementc | −.25 | |||||||

| Divorced*Verbal aggression | −.66 | |||||||

| Widowed*Verbal aggression | .40 | |||||||

| Divorced*Marital trouble | −17.66*** | |||||||

| Widowed*Marital trouble | −.35 | |||||||

| R 2 | .77 | .76 | .76 | .76 | .75 | .75 | .77 | .77 |

p ≤ .1

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001;

Centered variables.

Models 2–5 examine interaction effects involving equity factors, time spent together, and frequency of sex on the one hand and marital transition status on the other hand. No significant interactions emerged in these analyses. Model 6, on the other hand, shows a marginally significant interaction between marital disagreements and marital transitions. At greater levels of disagreement, the effect of divorce on depression becomes increasingly negative, consistent with a buffering effect.

Model 7 does not show any significant interaction between verbal aggression in the prior marriage and marital transition status on depressive symptoms. Model 8, on the other hand, shows a very significant interaction of marital transition status with whether the marriage was perceived to be in trouble (p < .001). That is, among those who perceived that their marriage was in trouble earlier on, divorce resulted in a lower level of depression, compared to those remaining married.

Discussion

Our primary interest in this study was to assess the extent to which marital quality might moderate the impact of marital termination on depression. The results suggest that respondents’ general feelings about the quality of their marriages (e.g., their marital happiness), their level of marital disagreement, and having a feeling that one’s marriage is in trouble moderate the positive effect of divorce on depressive symptoms. Thus, hypothesis 1, which states that lower marital quality weakens the corrosive influence of divorce on individuals’ depressive symptoms at a later point in time, is partially supported.

In this study, marital happiness alleviates the negative effect of divorce on depressive symptoms; the more marital happiness enjoyed before divorce, the more depressive symptoms people experience after divorce. This finding could well be driven either by divorces initiated by spouses rather than respondents, or the occurrence of traumatic events such as infidelity that suddenly disrupted an otherwise satisfactory marriage. For example, those who reported higher marital happiness are most likely not the ones who initially asked for a divorce. If the spouse is the one who initiated a divorce, an individual may feel a sense of betrayal, which strengthens the impact of divorce on depressive symptoms. Previous evidence suggests that who makes the decision of marital separation matters for psychological well-being (Hewitt & Turrell, 2011). Particularly, those who did not make the decision to separate report a lower level of mental health than those who were the initiators of the separation (Hewitt & Turrell, 2011).

This finding also echoes results of previous studies showing that higher marital satisfaction makes adjustment more difficult after a marital separation (Carr & Boerner, 2009). Individuals who recall a happy previous marriage may have to work hard to cope with a marital disruption (Bowlby, 1982).

On the other hand, having higher levels of marital disagreement or having a feeling that one’s marriage is in trouble weakens the relationship between subsequent divorce and depressive symptoms. Our findings echoed previous studies, suggesting that divorce can be a solution instead of a problem for a strained marriage (Wheaton, 1990). People can improve their well-being through divorce if they have an unhappy marriage (Booth & Hawkins, 2005). For example, individuals in stressful marriages feel relieved after divorce (Amato & Hohmann-Marriott, 2007). Although not surprising, this finding confirms that divorce can eventuate in better psychological outcomes for those with high-conflict or otherwise problematic relationships.

A major contribution of this study is in parsing out which aspects of marital quality appear to matter for psychological health after marital termination. Perceived marital happiness, the frequency of disagreements, and the perception that a marriage “is in trouble” are especially salient in this regard. On the other hand, we found that other aspects of marital quality (e.g., over or underbenefiting inequity, the amount of time spent together, sexual frequency, and verbal aggression) do not appear to condition the effect of divorce on subsequent mental health.

One explanation for the latter situation is that various aspects of marital quality have differential implications for the ongoing marriage as opposed to the aftermath of its disruption. For example, prior research suggests that house-work inequity has negative effects on individuals’ marital happiness and well-being during marriage (Longmore & DeMaris, 1997; Frisco & Williams, 2003). Our findings suggest that such perceptions are not influential for the impact of marital termination on depressive symptoms. One possible reason is that the measurement of under or overbenefit pertained mostly to household tasks such as childcare or daily chores. For older adults, although individuals may experience a reduction in benefits following marital termination, they may also experience a reduction in daily tasks as they only have to care for themselves. Similarly, if time spent apart or sex is not perceived as having the same level of importance as when individuals were young (Lindau et al., 2007), then they may not be applicable to the marriage in question. Thus, it is critical for future research to examine potential moderators of the effect of marital termination that are of particular concern to older couples.

In showing no significant interaction effects between verbal aggression and divorce on depressive symptoms, our findings are also at variance with a recent study by Kalmijn and Monden (2006). This discrepancy may be due to the fact that Kalmijn and Moden did not distinguish between NSFH items such as “argued heatedly or shouted at each other,” which represents a serious marital conflict, and “discussed disagreements calmly,” which represents a much more positive style (e.g., marital disagreement) of conflict resolution.

Our study also showed that, in terms of long-term consequences, marital status may not affect older adults’ psychological well-being very much as long as they are healthy and/or financially secure. After considering other factors such as income and health, there were no differences in levels of depressive symptoms between individuals who were still married and individuals who were widowed and between individuals who were still married and individuals who were divorced. Several authors have shown that good health and financial resources help minimize depressive symptomatology (Garatachea et al., 2009; Kasckow et al., 2013; Wang & Amato, 2000).

In contrast to the earlier studies, we found no interaction effects between previous marital quality and widowhood on depressive symptoms. For example, Carr et al. (2000) argued that older adults who had a conflict-ridden relationship before widowhood reported lower levels of yearning compared to widowed individuals who had higher levels of marital closeness and dependence on their spouses. One possible reason could be that our study examined only the depressive symptoms. Other aspects of well-being, such as anger or yearning, might reveal buffering or exacerbating effects of marital quality on widowhood. Future studies should examine other indicators of well-being that might be more sensitive to the moderating effect of marital quality as compared with divorce or widowhood.

Study limitations

There are some limitations to this study which may have biased the results. First, the NSFH has a question about physical violence between couples which was not tested as an aspect of marital quality in the study because of the limited number of cases reporting such abuse. Kalmijn and Monden (2006) found a positive association between physical aggression and depressive symptoms after divorce. However, since physical violence is not common among older couples, with only a few respondents experiencing such extreme events, it was not possible to test such interaction effects. Future studies could examine how such a stressful event plays a role in the etiology of divorce. Second, our study only tested depressive symptoms, whereas widowhood may cause other long-term psychological problems such as anger rather than depressive symptoms (Carr et al., 2000). Future studies should examine other mental health constructs that might be longer term sequelae of divorce or widowhood.

Conclusion

The present findings indicate that older adults are adversely affected by a divorce when they experience better marital quality before the disruption. On the other hand, previous marital quality does not interact with widowhood when examining the influence of widowhood on depressive symptoms. Future studies should consider a diverse range of conditions existing before marital transitions when examining the consequences of divorce or widowhood among older adults.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the valuable comments of Dr. Gary Lee on an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- Ackert LF, Church BK, & Deaves R (2003). Emotion and financial markets. Economic Review, 88, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, & Hohmann-Marriott B (2007). A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 621–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00396.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, & Hawkins DN (2005). Unhappily ever after: Effects of long-term, low-quality marriages on well-being. Social Forces, 84, 451–471. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GL, & Jensen TM (2015). Late-life divorce and postdivorce adult subjective well-being. Journal of Family Issues. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52, 664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Lin I-F (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Lin I-F, Hammersmith AM, & Wright MR (2016). Later life marital dissolution and repartnership status: A national portrait. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D (2004). Gender, preloss marital dependence, and older adults’ adjustment to widowhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 220–235. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00016.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, & Boerner K (2009). Do spousal discrepancies in marital quality assessments affect psychological adjustment to widowhood?. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 495–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00615.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Kessler RC, Nesse RM, Sonnega J, & Wortman C (2000). Marital quality and psychological adjustment to widowhood among older adults: A longitudinal analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55, S197–S207. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A (2010). Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72, 403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, & Marks NF (2008). Marital conflict, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(2), 377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00488.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D (2008). The waters we swim: Everyday social processes, macrostructural realities, and human aging. In Schaie KW & Abeles RP (Eds.), Social structures and aging individuals: Continuing challenges, (pp. 3–18). New York: Springer Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Das A (2013). Spousal loss and health in late life: Moving beyond emotional trauma. Journal of Aging and Health, 25, 221–242. doi: 10.1177/0898264312464498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A (2000). Till discord do us part: The role of physical and verbal conflict in union disruption. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00683.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A (2007). The role of relationship inequity in marital disruption. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(2), 177–195. doi: 10.1177/0265407507075409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz N, Molina O, MacMillan T, Duran L, & Swart E (2013). Attitudes toward divorce and their relationship with psychosocial factors among social work students. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 54, 505–518. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2013.810983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57, 4–15. doi: 10.2307/2786971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel SO, & Berry T (2006). The disposition effect and individual investor decisions: The roles of regret and counterfactual alternatives. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 7, 107–116. doi: 10.1207/s15427579jpfm0702_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freud S (1959). Mourning and melancholia. London: Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frisco ML, & Williams K (2003). Perceived housework equity, marital happiness, and divorce in dual-earner households. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 51–73. doi: 10.1177/0192513X02238520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garatachea N, Molinero O, Martínez-García R, Jiménez-Jiménez R, González-Gallego J, & Márquez S (2009). Feelings of well-being in elderly people: Relationship to physical activity and physical function. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 48, 306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gecas V (1989). The social psychology of self-efficacy. Annual Review of Sociology, 15, 291–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.15.1.291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt B, & Turrell G (2011). Short-term functional health and well-being after marital separation: Does initiator status make a difference? American Journal of Epidemiology, 173, 1308–1318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, & Monden CWS (2006). Are the negative effects of divorce on well-being dependent on marital quality? Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1197–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00323.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya Y, Doyle M, Henretta JC, & Timonen V (2013). Depressive symptoms among older adults: The impact of early and later life circumstances and marital status. Aging & Mental Health, 17, 349–357. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.747078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow JW, Karp JF, Whyte E, Butters M, Brown C, Begley A, ... Reynolds CF (2013). Subsyndromal depression and anxiety in older adults: Health related, functional, cognitive and diagnostic implications. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiiski J, Määttä K, & Uusiautti S (2013). “For better and for worse, or until ... ”: On divorce and guilt. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 54, 519–536. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2013.828980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin I-F (2008). Consequences of parental divorce for adult children’s support of their frail parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 113–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00465.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin I-F, & Brown SL (2012). Unmarried boomers confront old age: A national portrait. The Gerontologist , 52, 153–165. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, & Waite LJ (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(8), 762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, & Demaris A (1997). Perceived inequity and depression in intimate relationships: The moderating effect of self-esteem. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60, 172–184. doi: 10.2307/2787103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metsä-Simola N, & Martikainen P (2013). Divorce and changes in the prevalence of psychotropic medication use: A register-based longitudinal study among middle-aged finns. Social Science & Medicine, 94, 71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J (2013). Analyzing associations between mental health and social circumstances. In Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, & Bierman A (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health, (pp. 143–165). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_8 [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, & Giarrusso R (2010). Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1039–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00749.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symoens S, Colman E, & Bracke P (2014). Divorce, conflict, and mental health: how the quality of intimate relationships is linked to post-divorce well-being. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 220–233. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DA, Liu H, & Needham B (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz RL, Caserta M, & Lund D (2011). Grief, depressive symptoms, and physical health among recently bereaved spouses. The Gerontologist, 52, 460–471. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Luo Y, & Lewin AC (2009). Marital happiness and marital stability: Consequences for psychological well-being. Social Science Research, 38, 201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, & Amato PR (2000). Predictors of divorce adjustment: Stressors, resources, and definitions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 655–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00655.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B (1990). Life transitions, role histories, and mental health. American Sociological Review, 55, 209–223. doi: 10.2307/2095627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]