Significance

SMARCB1 is a tumor suppressor that is universally inactivated in renal medullary carcinoma (RMC), a highly aggressive malignancy that predominantly afflicts young individuals of African descent with sickle cell trait (SCT). We demonstrated using orthogonal in vitro and in vivo models that hypoxia induced by SCT leads to SMARCB1 degradation to protect cells from hypoxic stress. Accordingly, SMARCB1-deficient cells had a survival advantage in extreme hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, consistent with established clinical observations, SMARCB1 loss protected tumor cells from the hypoxia-inducing therapeutic inhibition of angiogenesis used for the treatment of other renal cell carcinomas. These results establish a physiological role for SMARCB1 in response to hypoxic stress and elucidate the connection between SCT and SMARCB1 loss observed in RMC.

Keywords: renal medullary carcinoma, hypoxia, SMARCB1, sickle cell trait

Abstract

Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC) is an aggressive kidney cancer that almost exclusively develops in individuals with sickle cell trait (SCT) and is always characterized by loss of the tumor suppressor SMARCB1. Because renal ischemia induced by red blood cell sickling exacerbates chronic renal medullary hypoxia in vivo, we investigated whether the loss of SMARCB1 confers a survival advantage under the setting of SCT. Hypoxic stress, which naturally occurs within the renal medulla, is elevated under the setting of SCT. Our findings showed that hypoxia-induced SMARCB1 degradation protected renal cells from hypoxic stress. SMARCB1 wild-type renal tumors exhibited lower levels of SMARCB1 and more aggressive growth in mice harboring the SCT mutation in human hemoglobin A (HbA) than in control mice harboring wild-type human HbA. Consistent with established clinical observations, SMARCB1-null renal tumors were refractory to hypoxia-inducing therapeutic inhibition of angiogenesis. Further, reconstitution of SMARCB1 restored renal tumor sensitivity to hypoxic stress in vitro and in vivo. Together, our results demonstrate a physiological role for SMARCB1 degradation in response to hypoxic stress, connect the renal medullary hypoxia induced by SCT with an increased risk of SMARCB1-negative RMC, and shed light into the mechanisms mediating the resistance of SMARCB1-null renal tumors against angiogenesis inhibition therapies.

Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC), which is uniformly characterized by the complete loss of the SMARCB1 tumor suppressor, is a highly aggressive malignancy that predominantly afflicts young individuals of African descent harboring sickle cell trait (SCT) (1), which is characterized by increased sickling of red blood cells in the renal medulla. Regional ischemia induced by red blood cell sickling in the renal medulla has been hypothesized to be a key step in RMC pathogenesis (2). While hypoxia occurs normally in the renal medulla (2), it is elevated in RMC tumors that purportedly arise from the collecting ducts of the renal medulla (3). Indeed, RMC tumors demonstrate a hypoxia signature (4), as well as are refractory to all tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) drugs that target the vascular endothelial growth factor hypoxia signaling pathways and are commonly used for treating all other renal cell carcinomas (5). A striking majority of RMC patients harbor SCT, suggesting a strong connection between SCT and RMC pathogenesis (2, 6). Accordingly, we have previously shown that conditions that aggravate renal medullary hypoxia, such as high-intensity physical exercise, increase the risk of RMC in individuals with SCT and in animal models (7).

To better understand RMC pathogenesis and its resistance to angiogenesis inhibition therapy, we investigated the connection between SMARCB1 loss and hypoxia under the setting of SCT. We found that hypoxia induces SMARCB1 protein downregulation in renal cells and that loss of SMARCB1 protects cells from hypoxic stress in vitro and in vivo. These findings elucidate the selective evolutionary pressure to lose SMARCB1 during RMC pathogenesis and identify a role for SMARCB1 as a critical regulator of cellular response to hypoxic stress in epithelial renal cells.

Results

Red Blood Cell Sickling Induces Chronic Renal Medullary Hypoxia in Mice with SCT.

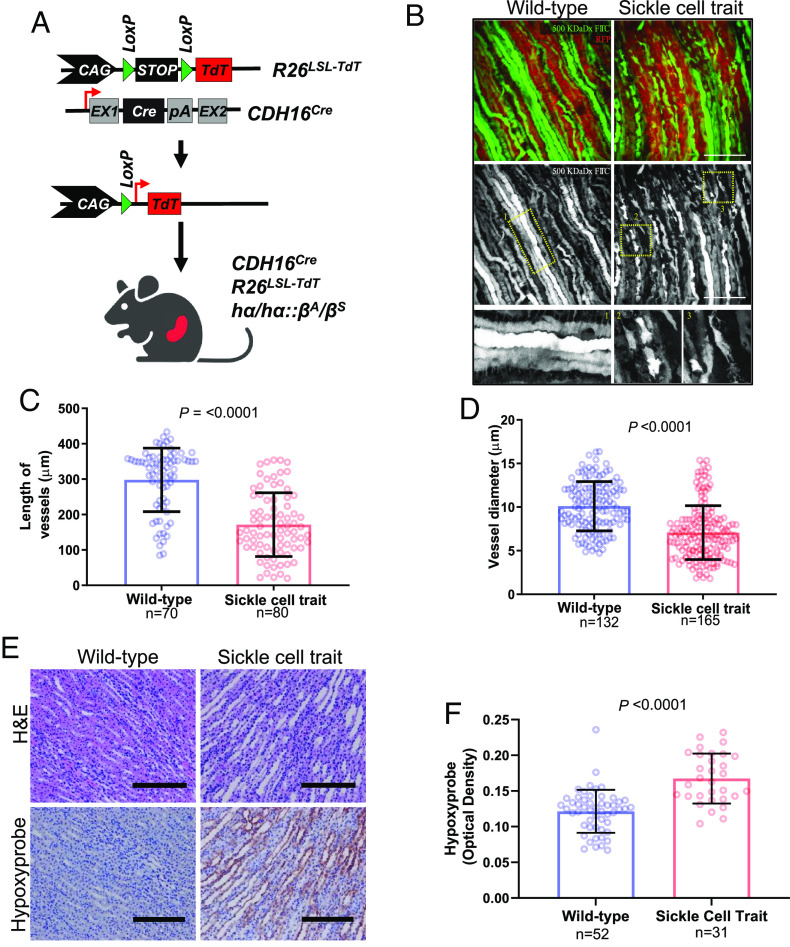

We previously demonstrated that mice with SCT experience significantly increased renal hypoxia after external perturbations, such as high-intensity exercise, when compared to wild-type counterparts, suggesting that sickled red blood cells aggravate renal ischemia under stress (7). To elucidate the association between renal ischemia and SCT, we generated a genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) of SCT that leverages a fluorescence reporter for the identification of epithelial structures in vivo. Specifically, the CDH16Cre strain was crossed with conditional Rosa26LSL-TdT mice and hα/hα::βS/βS mice to generate a GEMM of SCT (hα/hα::βA/βS) that enabled tissue-specific activation of the TdTomato (TdT) fluorescence reporter in the kidney epithelium (Fig. 1A). Both SCT and control GEMM mice expressed human hemoglobin A (HbA), but SCT mice harbored the sickle cell mutation in one allele of the HbA beta-subunit (hα/hα::βA/βS), whereas control GEMM mice harbored wild-type alleles (hα/hα::βA/βA). By leveraging the TdT fluorescence reporter and injected dextran conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), our GEMM models enabled the evaluation of microvasculature integrity and blood flow in the renal inner medulla.

Fig. 1.

Renal ischemia is associated with chronic hypoxia in sickle cell trait mouse model. (A) Schematic of genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) of SCT. (B) 3D image reconstruction of renal epithelia (RFP) and FITC-dextran (GFP) in adult mice (n = 4 to 5) with kidney-specific CDH16Cre and conditional R26LSL-Tom (C and D) Quantification of the diameter (C) and length (D) of the renal blood vessels (10 vessels/image, 3 locations/vessel). (E) IHC of mouse kidneys after injection with Hypoxyprobe. (F) Quantification of the optical density of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) staining for 20× images was done using ImageJ. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test.

We found that the renal inner medulla of adult mice with SCT harbored discontinuous and disorganized blood vessels, including significantly shorter diameters (P-value < 0.0001) and lengths (P-value < 0.0001) of blood vessels, when compared to those observed in control mice (Fig. 1 B–D). To assess whether SCT-associated blood vessel changes could elevate hypoxia in the renal inner medulla, we injected intraperitoneal (IP) pimonidazole hydrochloride (Hypoxyprobe), a chemical probe that binds to tissue with oxygen tension less than 10 mm Hg, into our SCT and control models. Our findings confirmed hypoxia in the renal inner medulla of SCT mice, where SCT-associated microvascular changes were previously observed (Fig. 1 B–D), but not in wild-type controls (P-value < 0.0001) suggesting that the medullary parenchyma is chronically exposed to a hypoxic environment in SCT mice (Fig. 1 E and F). These results demonstrate that chronic hypoxia is present in the renal inner medulla of SCT mice.

SMARCB1 Is Degraded via the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System during Hypoxia.

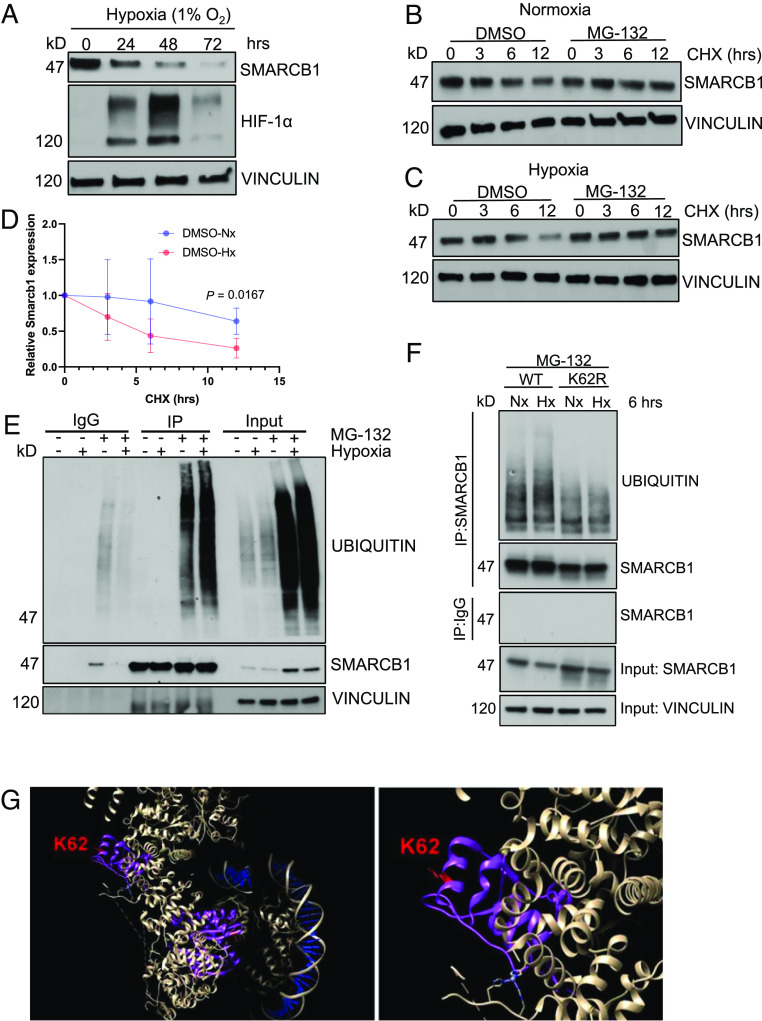

We next investigated the effect of hypoxia on SMARCB1 expression in the epithelial cells of the renal medullary collecting ducts. First, we assessed SMARCB1 protein levels in an in vitro epithelial model derived from the renal inner medullary collecting ducts (mIMCD-3) of a mouse model (8). Because the oxygen level of the renal medulla is approximately 2%, cells were placed in a hypoxia chamber set at 1% oxygen to mimic an extreme hypoxic state of the kidney for periods of 24, 48, and 72 h. We additionally found that SMARCB1 protein levels were inversely associated with oxygen levels, with the most severe degradation of SMARCB1 observed at 0.5% and 1% oxygen over 24 h, while degradation decreased at 2% oxygen, which is representative of physiological normoxia, and higher (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). Hypoxia chambers set at 21% oxygen were used as the normoxia control (9). Western blotting analysis showed that SMARCB1 protein levels in mIMCD-3 cells gradually decreased after prolonged periods of exposure to hypoxia (1%) over 72 h, with the strongest SMARCB1 depletion occurring at 72 h (Fig. 2A). Parallel immunoblotting analysis of HIF-1α, a cellular marker of acute hypoxia, showed increasing levels up to 48 h and a strong reduction at the more chronically hypoxic 72 h timepoint (Fig. 2A). These results are consistent with previous studies that have shown a reduction of HIF-1α at 72 h of hypoxia (10).

Fig. 2.

SMARCB1 is degraded via ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of mIMCD-3 cells after increasing time exposure to hypoxia (1% oxygen). (B) Cycloheximide chase assay of mIMCD-3 cells in 24 h of normoxia and (C) 24 h of hypoxia. Cells were treated with 20 μM cycloheximide for 0, 3, 6, and 12 h. (D) Quantification of SMARCB1 protein expression in mIMCD-3 after cycloheximide (CHX) chase experiment in 24 h of growth in normoxia and hypoxia. (E) Immunoprecipitation (IP) analysis of SMARCB1 ubiquitination after 6 h of hypoxia treatment. (F) MSRT1 cells ectopically overexpressing SMARCB1WT and SMARCB1K62R were cultured in 6 h of normoxia (21% oxygen) and hypoxia (1% oxygen) coupled with 3 h of treatment with 50 μM MG-132 to prevent proteasome degradation for subsequent immunoprecipitation assay. Protein analysis was then used to detect ubiquitin levels on SMARCB1. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test. (G) Crystal structure of SMARCB1 (purple) in the SWI/SNF complex (white) bound to DNA (blue) using cryoelectron microscopy. Lysine residue 62 is indicated in red. The crystal structure was obtained from He et al. and UCSF Chimera software (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/download.html) was used to visualize crystal structure.

To determine whether depletion of SMARCB1 under hypoxic conditions was driven by ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation, we treated mIMCD-3 cells with 20 μM cycloheximide (CHX), an inhibitor of protein translation, for 0, 3, 6, and 12 h coupled with 25 μM proteasome inhibitor MG-132 for 3 h. Our findings showed a significant reduction in SMARCB1 protein levels after 12 h of treatment with CHX treatment in mIMCD-3 cells exposed to 24 h of hypoxia compared to an equivalent time in normoxia (Fig. 2 B–D). Notably, the addition of MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, rescued SMARCB1 protein levels to >85% of pre-CHX treatment levels in mIMCD-3 cells under either normoxia or hypoxia (Fig. 2 B and C), thus indicating that the depletion of SMARCB1 protein levels in mIMCD-3 cells is mediated by ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Altogether, our data indicated that hypoxia accelerates the ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of SMARCB1 in mIMCD-3 cells.

To better understand how hypoxia accelerates SMARCB1 degradation, we investigated whether SMARCB1 ubiquitination was upregulated under hypoxic conditions. We first used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology to generate MSRT1, a SMARCB1-deficient (SMARCB1Null) mouse renal tumor cell line (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). To characterize on- and off-target sgRNA effects, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) analysis on the MSRT1 cell line in comparison to corresponding normal mouse kidney cells. Using Integrative Genomics Viewer, our WES analysis showed that there is efficient sgRNA-targeted cutting of Smarcb1 (exons 1 and 2) and Cdkn2a/b (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–D). WES analysis also indicated that sgRNA for Trp53 did not result in CRISPR/Cas9 cutting of Trp53 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E), but there was a spontaneous focal alteration at both exon 3 and 4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F), explaining the observed loss of p53 protein in immunoblotting analysis after subjecting cells to 10 s of exposure to ultraviolet light to induce the expression of p53 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2H).

Ectopic expression of SMARCB1 was then induced in wild-type SMARCB1 (SMARCB1WT) MSRT1 cells. SMARCB1Null and SMARCB1WT MSRT1 cells were cultured in normoxia and hypoxia conditions for six hours and subsequently treated with 25 μM MG-132 for four hours prior to lysing cells for further immunoprecipitation (IP) analysis. Our findings demonstrated that ubiquitination was observed upon proteasome inhibition in both normoxic and hypoxic conditions but was significantly higher in hypoxia compared to normoxia (Fig. 2E). Together, our data further suggested an increase in SMARCB1 degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system under hypoxic conditions.

Therefore, we hypothesized that SMARCB1 is being ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded at the protein level. To investigate this question, we used site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) to mutate to arginine the lysine residues that have been shown in prior studies to be ubiquitinated in SMARCB1 (SI Appendix, Table S1) (11–20). SDM was also used to induce known hotspot and missense mutations that occur in human cancers (R377H, K363*, K364R) based on the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer database (21). Mutant and wild-type SMARCB1 protein expression were reconstituted in MSRT1 cells. Cells were then cultured for 48 h under hypoxia and normoxia, and immunoblot analysis was used to compare the expression of SMARCB1 mutants and SMARCB1WT under hypoxia to that under normoxia. Consistently, SMARCB1WT protein levels were degraded to less than half of those observed under normoxic conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Our results showed that the K62R mutant is the most efficient at impairing the degradation of SMARCB1 after 48 h of exposure to 1% oxygen in comparison to their normoxia control (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B–D). We, therefore, chose to use SMARCB1K62R as our low-degradation SMARCB1 mutant for further characterization studies.

We hypothesized that the K62R mutant was preventing the degradation of SMARCB1 protein by disrupting ubiquitination. To investigate this, we performed an IP assay for SMARCB1 after 6 h of exposure to normoxia and hypoxia coupled with 3 h of treatment with 50 μM MG-132 to prevent proteasome degradation for sequential protein analysis of ubiquitin protein on SMARCB1WT and SMARCB1K62R. Our results in Fig. 2F showed that SMARCB1K62R has consistently less ubiquitination compared to SMARCB1WT, supporting the notion that lysine residue 62 is a major site of ubiquitination on SMARCB1 for ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation.

To interrogate whether the K62R mutation is adversely affecting SMARCB1 integrity, we examined the 3.7-angstrom-resolution cryoelectron microscopy structure of the human SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex bound to the nucleosome that was previously published by He et al. (22). Using the UCSF Chimera software (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/download.html), we visualized SMARCB1 protein shown in purple in Fig. 2G. The structure analysis showed that lysine residue 62 is in a region of SMARCB1 that does not interact with other subunits of the SWI/SNF complex or the bound nucleosome. The positioning of lysine residue 62 suggests that it is a readily accessible region of the protein that enables rapid modulation at the protein level, such as ubiquitination, in response to environmental changes. Therefore, its mutation most likely only disrupts ubiquitination and sequential degradation.

SMARCB1 Protein Expression Is Significantly Lower in the Renal Medullary Tubule Cells of RMC Patient Nephrectomy Samples and Mouse Models with SCT.

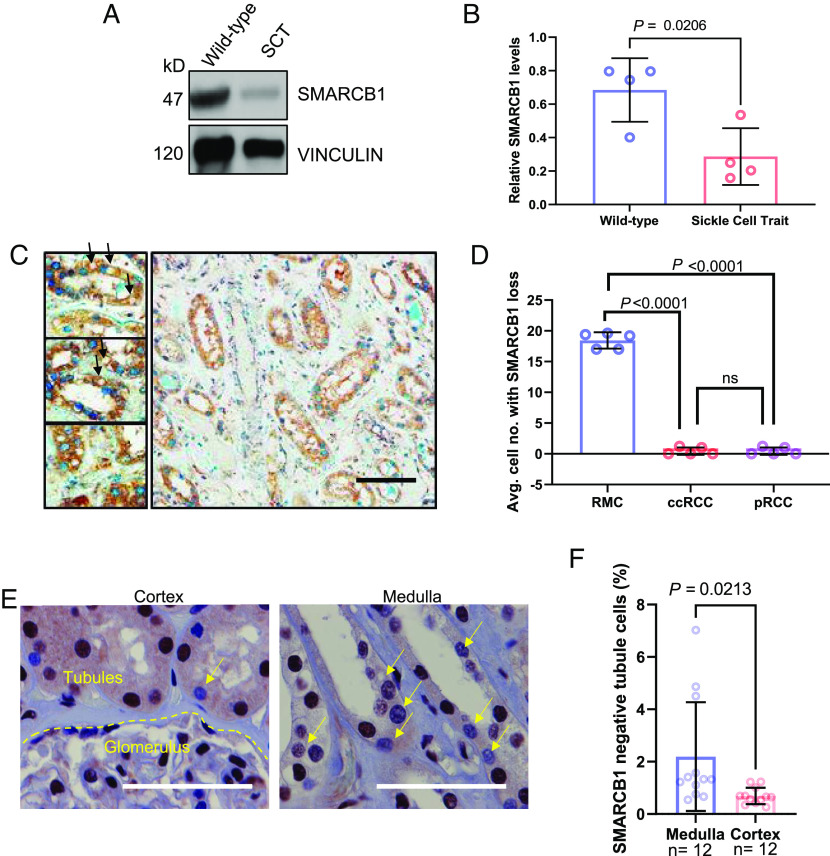

Because oxygen tension is a critical factor for SMARCB1 protein stability and since kidneys of mice with SCT are hypoperfused (Fig. 1), we assessed SMARCB1 protein levels in renal tissues harvested from our SCT models. Immunoblotting analysis revealed a decrease in SMARCB1 protein levels specifically in kidneys from SCT mice when compared to those from WT controls (Fig. 3 A and B). To further corroborate the relevance of these observations, we performed an IHC analysis to compare SMARCB1 protein levels between normal adjacent renal medullary tissue from nephrectomy samples of patients with RMC (n = 5), the most common SMARCB1-deficient renal cell carcinoma, with that of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) (n = 5) and papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC) (n = 5), the two most common SMARCB1-positive renal cell carcinomas. Our findings revealed a significantly higher number of tubule cells that displayed lower or no positivity for SMARCB1 nuclear signal in morphologically normal renal medullary tissue from RMC patients with SCT when compared to those from ccRCC or pRCC patients who do not have SCT (Fig. 3 C and D). In addition, we utilized IHC analysis to compare the protein expression levels of SMARCB1 in the cortical and medullary regions of normal adjacent renal tissue from nephrectomy samples of two patients with RMC, both of whom had SCT. We found that, compared with the cortex, the inner medulla had significantly higher numbers of tubules with negative SMARCB1 protein expression by IHC (Fig. 3 E and F). Altogether, these data indicate that there is a selective pressure to decrease SMARCB1 protein levels under hypoxic conditions, leading to decreased renal medullary SMARCB1 in the setting of SCT.

Fig. 3.

SMARCB1 protein expression is significantly lower in the renal medullary tubule cells of RMC patient nephrectomy samples and mouse models with sickle cell trait. (A) Representative image of immunoblotting analysis of kidney lysates from wild-type mice and mice with SCT. (B) Quantification of immunoblotting analysis of SMARCB1 protein in mouse kidney lysates. (C) RMC adjacent kidneys with SMARCB1 loss characterized using IHC analysis. SMARCB1 is indicated in blue (Alkaline phosphatase) staining and eIF2-alpha is indicated in HRP 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. The arrows indicate SMARCB1 loss. (D) Quantification of SMARCB1 protein in IHC experiment comparing normal adjacent kidney tissue in different renal tumors. Five 40X images were taken per patient and quantified. The average of five images is shown per patient and represented as a single dot in the plot. (E) IHC analysis of SMARCB1 protein expression in normal adjacent renal tissue from nephrectomy samples of two patients with RMC. Yellow arrows indicate SMARCB1-deficient tubule cells. (F) Quantification of SMARCB1-deficient tubule cells. The number of SMARCB1-deficient tubule cells was expressed as a percentage of total tubule cells in the 40X images. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test.

Inhibiting the Degradation of SMARCB1 Is Detrimental to Renal Tumor Cell Growth under Hypoxic Stress.

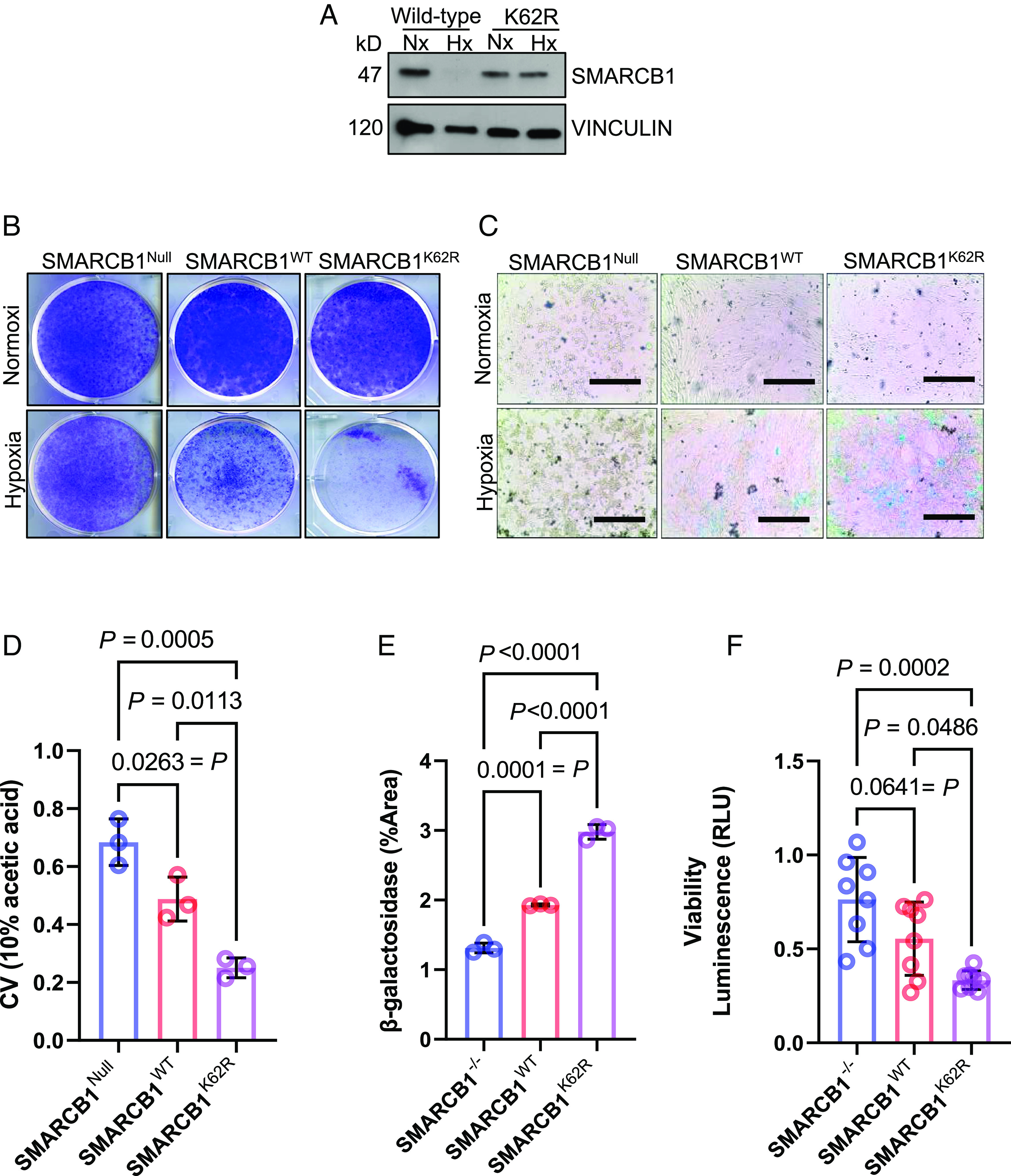

To investigate the benefit conferred by SMARCB1 degradation during hypoxia, we used a clonogenic assay to assess the effect of impairing SMARCB1 degradation on renal tumor cell survival under normoxia and hypoxia. MSRT1 cells were reconstituted with SMARCB1WT or SMARCB1K62R and the parental MSRT1 (SMARCB1null) cells were used as the control. Exposure to hypoxia significantly decreased SMARCB1WT protein levels expressed by MSRT1 cells whereas SMARCB1K62R levels were unaffected by hypoxia (Fig. 4A). There were no significant growth differences between SMARCB1Null, SMARCB1WT, and SMARCB1K62R MSRT1 cells grown in normoxia, whereas all cells had decreased growth in hypoxia (Fig. 4B). SMARCB1K62R reconstitution significantly decreased the growth of MSRT1 cells under hypoxia when compared to the growth of MSRT1 cells harboring either SMARCB1Null or SMARCB1WT (Fig. 4 B–F). These results suggest that SMARCB1 degradation confers a proliferative advantage to renal tumor cells specifically under the context of hypoxia.

Fig. 4.

SMARCB1-deficient tumors are resistant to hypoxic stress, while SMARCB1-proficient tumors are sensitive to hypoxic stress. (A) Western blotting analysis of MSRT1 cells overexpressed with either SMARCB1WT or SMARCB1K62R. (B) Clonogenic assay of MSRT1 tumors overexpressed with either SMARCB1Null, SMARCB1WT, and SMARCB1K62R grown in either normoxia or hypoxia. (C) Representative images of β-galactosidase staining of MSRT1 cells overexpressed with SMARCB1Null, SMARCB1WT, and SMARCB1K62R. (D) Quantification of clonogenic assay. Crystal violet was dissolved from cells using 10% acetic acid. (E) Quantification of β-galactosidase using FIJI ImageJ software. (F) Luminescent (RLU) activity indicating cell viability in MSRT1 with SMARCB1Null, SMARCB1WT, and SMARCB1K62R after prolonged exposure to normoxia and hypoxia. For all quantification experiments shown in D–F, the cell viability of cells in hypoxic condition was normalized to its corresponding normoxic condition. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test.

To further investigate the mechanism underlying the growth inhibition observed in our clonogenic assay, we used a beta-galactosides (β-gal) assay to evaluate cellular senescence in MSRT1 cells harboring reconstituted SMARCB1WT or SMARCB1K62R with SMARCB1Null as the control. Our results showed that under hypoxic conditions, significantly elevated β-galactoside positivity was detected in both SMARCB1K62R and SMARCB1WT cells, with significantly higher levels of senescence observed in SMARCB1K62R cells, after 6 d of growth (Fig. 4 C and E). In addition, cell viability of SMARCB1K62R cells cultured under hypoxia for 24 h was significantly lower than those of SMARCB1Null and SMARCB1WT cells (Fig. 4F). Together, these data suggest that SMARCB1 degradation may enable the survival and proliferation of renal cells under hypoxic conditions.

SMARCB1 Loss Confers a Survival Advantage for Renal Tumor Cells under Hypoxic Stress In Vivo.

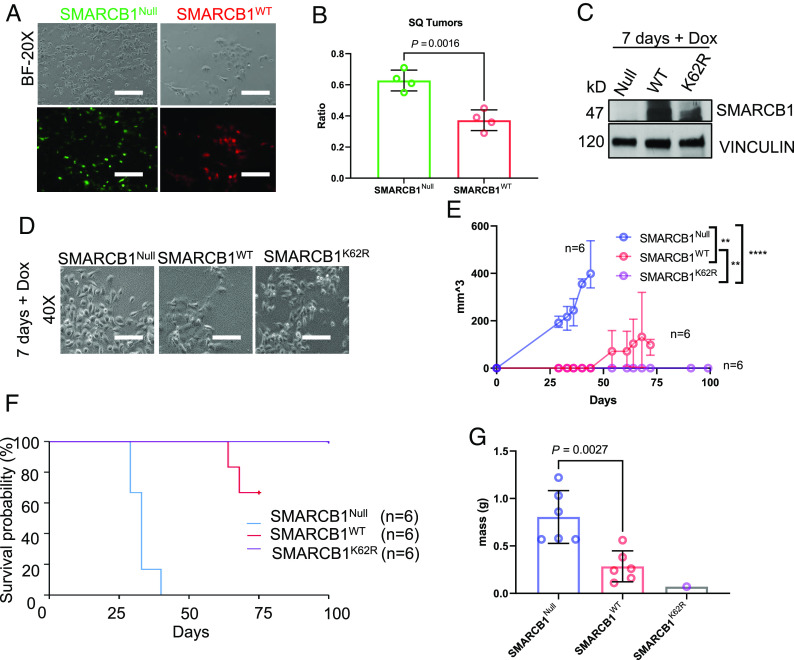

To evaluate the growth advantage in vivo of SMARCB1 deficiency in renal tumor cells, we used MSRT1 cells and performed a competition assay with SMARCB1Null cells endogenously expressing green fluorescent reporter (GFP) and SMARCB1WT cells labeled ectopically with red fluorescent reporter (RFP) (Fig. 5A). A 1:1 mixture of SMARCB1Null (GFP only) and SMARCB1WT cells (GFP + RFP) was then subcutaneously transplanted into immune-compromised NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice. Tumors were harvested for flow cytometry analysis upon reaching approximately 100 mm3 in size. Analysis of GFP (SMARCB1Null) versus GFP/RFP (SMARCB1WT) showed that SMARCB1Null cells were significantly enriched compared to SMARCB1WT cells in renal tumors (Fig. 5B), supporting that SMARCB1Null cells have a growth advantage in a hypoxic tumor environment.

Fig. 5.

SMARCB1-deficient tumor cells are more resistant to hypoxia and expand under hypoxic conditions. Preventing the degradation of SMARCB1 significantly impairs tumor expansion. (A) Microscopic images of SMARCB1Null mouse renal tumors (GFP) and SMARCB1WT cells (GFP/RFP) prior to subcutaneous injection into NSG mice. (B) Flow cytometry evaluation of SMARCB1Null and SMARCB1WT tumor cells that were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and injected subcutaneously into NSG mice. (C) Immunoblotting analysis of SMARCB1 protein expression in RMC219-tet-empty vector (SMARCB1Null) and RMC219-tet-inducible SMARCB1WT and RMC219-tet-inducible SMARCB1K62R after 7 d of treatment with 2 μg of Doxycycline (DOX). (D) Corresponding microscopic images of RMC219-tet-inducible cells showing that cells are healthy prior to subcutaneous injection in NSG mice. (E) Growth curve of subcutaneous tumors in NSG mice. (F) Kaplan–Meier survival curve of RMC219 subcutaneous tumors. For time-to-event event-free survival analysis, 200 mm3 was set as the endpoint. (G) Final tumor mass of RMC219 subcutaneous tumors. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test.

To investigate the effect of SMARCB1K62R, SMARCB1WT, and SMARCB1Null on tumor growth in vivo, we generated RMC patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models by using RMC219 cells (23). Specifically, RMC219 cells were transduced with either tetracycline-inducible pIND20-fSNF5-HA vector encoding for SMARCB1WT or SMARCB1K62R, or an empty vector (EV) as the negative control. Cells were grown in vitro on doxycycline (DOX) for 7 d to induce the expression of SMARCB1WT or SMARCB1K62R before 50,000 cells were transplanted subcutaneously into NSG mice (Fig. 5 C and D). Our findings demonstrated that SMARCB1Null tumors grew faster than SMARCB1WT and SMARCB1K62R tumors over the 7 d post-transplantation, with SMARCB1K62R tumors showing almost no growth (Fig. 5E). Accordingly, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that survival of SMARCB1Null PDX models was significantly lower than that of SMARCB1WT and SMARCB1K62R PDX models (Fig. 5F). Moreover, all SMARCB1K62R PDX models survived until day 100, whereas only 4 out of 6 SMARCB1WT PDX models survived until day 75 (Fig. 5F). These remaining four SMARCB1WT PDX models were euthanized at day 75 for tissue harvesting. SMARCB1K62R PDX models were monitored until day 100, at which point small lesions were still barely palpable. Final tumor weight showed that tumor masses in SMARCB1Null PDX models were significantly greater than those from the two PDX models with reconstituted SMARCB1 (Fig. 5G). These data suggest that disruption of ubiquitin-mediated degradation of SMARCB1 confers a growth disadvantage to RMC tumor cells in vivo.

SCT Promotes Tumor Cell Expansion in SMARCB1-Deficient Renal Tumors.

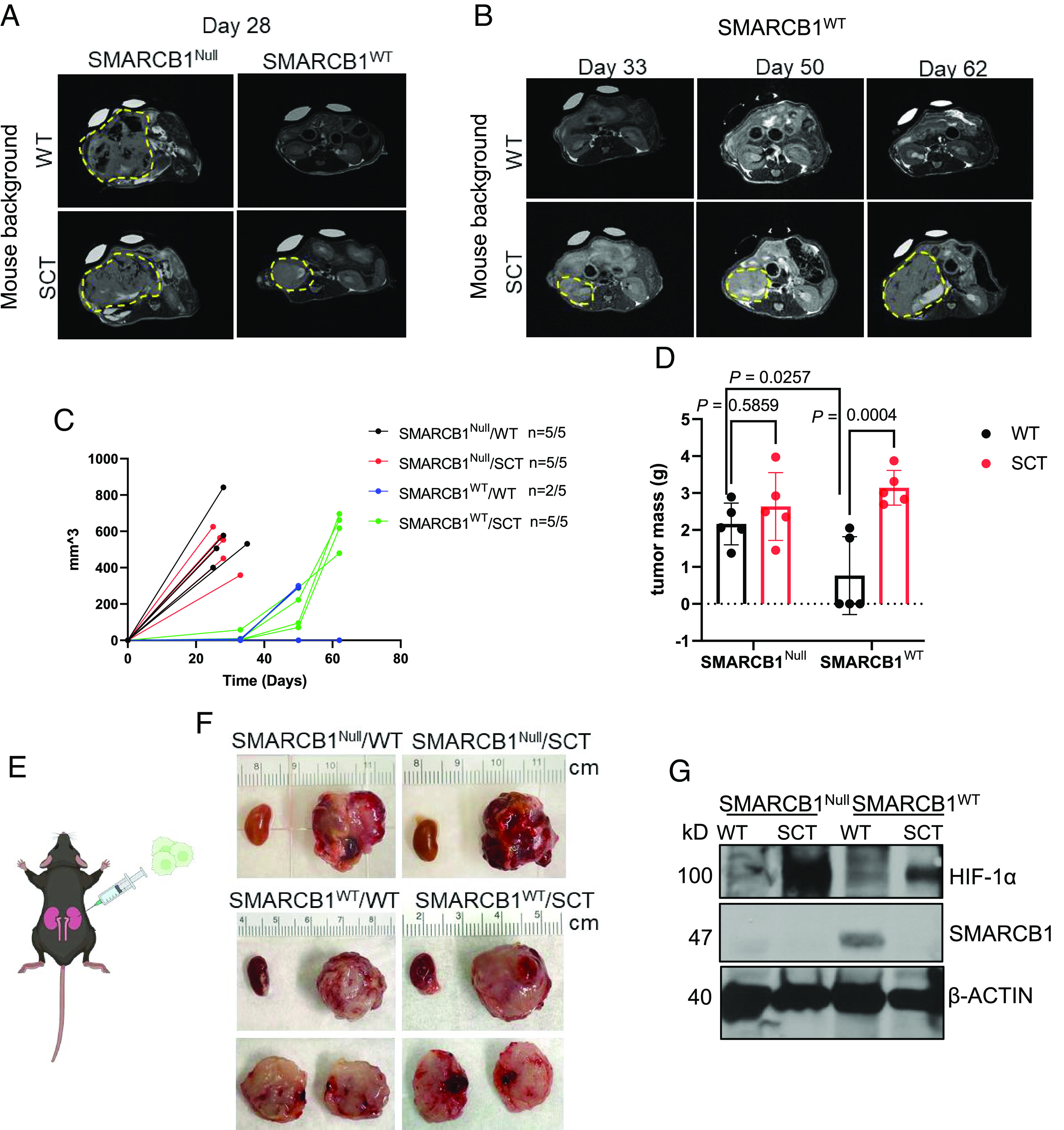

We next sought to investigate the effect of SCT on renal tumor cell expansion using a syngeneic mouse model generated by crossing the Townes SCT mouse with the Rosa26-Cas9 knock-in mouse strain that had been kept on a C57BL/6J pure background. To recapitulate the human phenotype, we orthotopically transplanted MSRT1 reconstituted with SMARCB1Null or SMARCB1WT into the right kidneys of adult mice with SCT and wild-type mice (Fig. 6E). The right kidney was chosen for tumor cell transplantation because RMC predominantly affects the right kidneys in patients (2, 6, 24), and the right renal medulla is more hypoxic than the left in the setting of SCT (7). Tumor burden in all mice were monitored with MRI every 2 to 3 wk. SMARCB1Null renal tumors developed rapidly, and all wild-type (n = 5) and SCT (n = 5) mice harboring SMARCB1Null renal tumors became moribund and were euthanized within 40 d after initial transplantation (Fig. 6C). Conversely, SMARCB1WT tumors grew at a much slower rate than that of SMARCB1Null renal tumors in both wild-type and SCT background mice posttransplantation (Fig. 6 A and B). Notably, SMARCB1WT tumors were detected earlier in SCT mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). While two of the five wild-type mice harboring SMARCB1WT tumors became moribund from complications related to their tumor burden, the remaining three wild-type mice harboring SMARCB1WT tumors continued to show no indications of tumor growth up to 80 d post-transplantation (Fig. 6C). Conversely, all SCT mice harboring SMARCB1WT tumors became moribund by day 70 post-transplantation and were euthanized due to complications from tumor burden (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Sickle cell trait promotes tumor growth and aggressiveness in SMARCB1-deficient tumors. (A and B) Representative coronal T2-weighted MRI sections of tumor-bearing mice after orthotopic injection of MSRT1-SMARCB1Null and MSRT1-SMARCB1WT tumor cells into right kidney of wild-type mice (n = 5) and mice with sickle cell trait (n = 5). (C) Growth curve of primary kidney tumors. Tumor volume was quantified using coronal T2-weighted MRI sections at various timepoints after initial orthotopic injection of cells. ImageJ was used to calculate the tumor volume from T2-weighted MRI sections. (D) Final tumor mass of primary kidney tumors. (E) Schematic of orthotopic right kidney injections of MSRT1 tumor cell line. (F) Gross images of right primary kidney tumor compared to normal left kidney. Ruler increments are in cm. (G) Immunoblotting analysis of SMARCB1 and HIF-1α protein expression in orthotopic kidney tumors. β-ACTIN was used as the internal control for the immunoblotting analysis. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test.

There was no significant difference in final tumor mass between wild-type and SCT mice harboring SMARCB1Null renal tumors (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, the final mass of SMARCB1WT tumors in SCT mice was comparable to SMARCB1Null tumors in wild-type or SCT mice, while the mass of SMARCB1WT tumors in wild-type mice was significantly lower than the mass of SMARCB1Null tumors in wild-type or SCT mice (Fig. 6D). To investigate whether renal hypoxia in the SCT mice was promoting the growth of SMARCB1WT cells transplanted into the SCT background mice, using HIF-1a as a marker of hypoxia we compared the protein levels of SMARCB1 in the MSRT1 kidney tumor transplants to hypoxia levels based on HIF-1a expression (Fig. 6G). We found that the levels of SMARCB1 protein were lower in the SMARCB1WT tumors transplanted in mice with SCT background where there was greater HIF-1a protein expression, further supporting our hypothesis that SMARCB1 is degraded in the highly hypoxic conditions created by red blood cell sickling (Fig. 6G). However, contrary to the results of the in vitro clonogenic assay in which SMARCB1Null and SMARCB1WT cells had equivalent growth in normoxia (Fig. 4 B–D), SMARCB1WT tumor cells failed to grow in the wild-type background mice but grew in the SCT background mice (Fig. 6C). This result can be explained by the fact that SMARCB1WT tumors from the wild-type background are less hypoxic than the SCT background based on HIF-1α expression (Fig. 6G). Therefore, the wild-type hypoxic microenvironment conferred a selective pressure against tumors reconstituted with SMARCB1WT, causing less growth. In contrast, in vitro experiments were performed in highly oxygenated conditions of 21% oxygen in which there is no HIF-1α expression (Fig. 2A). Together, our findings demonstrated that SMARCB1 degradation promotes renal tumor cell expansion in the hypoxic microenvironment of the kidney under the setting of SCT, thus elucidating the connection between SMARCB1 loss and SCT that has been observed in patients with RMC.

SMARCB1Null Renal Tumors Are Insensitive to Angiogenesis Inhibition.

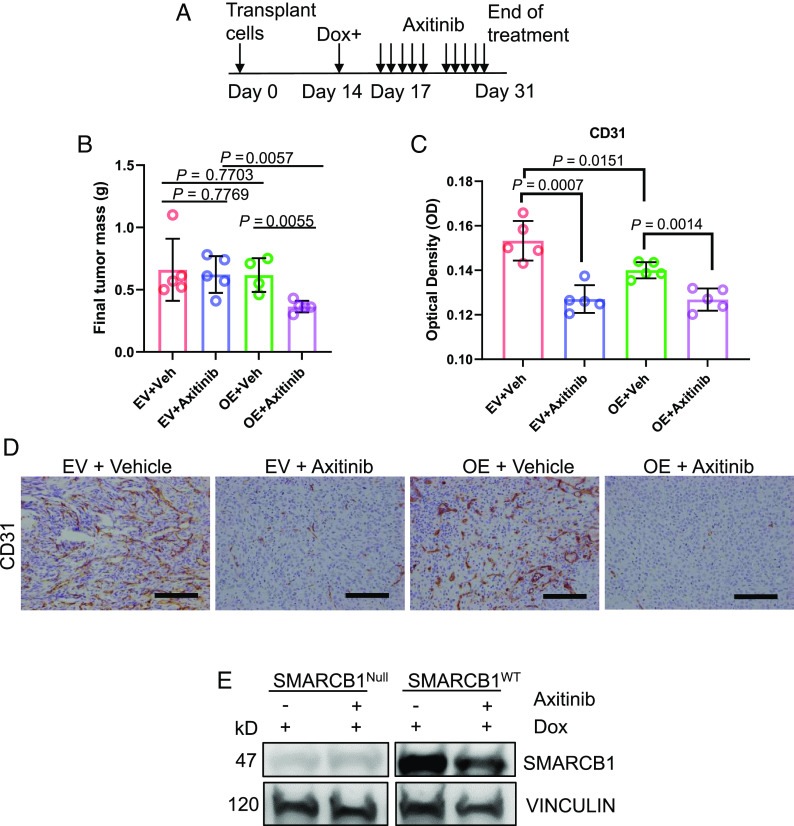

Unlike other renal cell carcinomas, RMC is refractory to TKIs that target angiogenesis (24). We hypothesized that this unique resistance to the hypoxic conditions induced by angiogenesis inhibitors is due to the protective effect of SMARCB1 loss. To test this hypothesis, we used in vivo RMC219 xenografts transduced with tetracycline-inducible pIND20-fSNF5-HA (OE) vector for SMARCB1WT re-expression or with a corresponding EV as the control, because SMARCB1WT reconstitution can potentially decrease the proliferation of RMC219 in vivo. Transplanted RMC219 cells were allowed to grow to equal volumes of approximately 100 mm3 for 14 d before mice were then placed on DOX water for three days to activate SMARCB1WT (Fig. 7A). Mice were kept on DOX water for the entire duration of the experiment. On day 17, RMC219 xenograft mice were orally treated with 30 mg/kg of axitinib (Selleckchem), a selective anti-angiogenic TKI, or vehicle (control) for 2 wk (5 d treated and 2 d off), and tumor growth was monitored every 3 to 4 d throughout treatment (Fig. 7A). Our findings showed that the final tumor mass between SMARCB1Null tumors in RMC219 xenograft mice and those in vehicle controls were similar, indicating that SMARCB1Null RMC219 tumors were resistant to axitinib (Fig. 7B). However, SMARCB1WT tumors in RMC219 xenograft mice treated with axitinib demonstrated significantly reduced growth compared to those treated with vehicle control (Fig. 7B). All tumors were harvested for IHC analysis on day 31. Our findings showed that tumors treated with axitinib harbored significantly less CD31 (cluster of differentiation 31), a marker of endothelial cells, thus confirming the on-target effect of axitinib on angiogenesis (Fig. 7 C and D). We also performed an immunoblot analysis of the tumors harvested on day 31 and confirmed that SMARCB1 protein expression remained relatively stable for untreated tumors. Expectantly, there was a reduction in SMARCB1 protein expression after axitinib treatment as result of increased hypoxia (Fig. 7E). Altogether, these results suggest that SMARCB1 loss confers a selective survival advantage under the context of therapeutic angiogenesis inhibition.

Fig. 7.

SMARCB1Null renal tumors are insensitive to angiogenesis inhibition. (A) Axitinib treatment schedule. (B) Final tumor mass of RMC219-tet-inducible cell lines that were injected subcutaneously (SQ) into NSG mice. Each dot represents one mouse. (C) and corresponding quantification of the optical density of CD31 IHC analysis. (D) Representative IHC image of CD31 staining of subcutaneous tumors treated with axitinib. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test. (E) Representative immunoblotting analysis of final tumors after axitinib treatment. Data are expressed as mean value ±SD, with the P value calculated by Student’s t test.

Discussion

Elucidation into the mechanisms driving RMC is urgently needed to improve the therapeutic options against this aggressive cancer. Here, we have assessed the survival advantage enabled by SMARCB1 loss, which occurs in all RMC cases, under the setting of SCT, which is strongly associated with the development of RMC. Our findings demonstrated that SMARCB1 is ubiquitinated and degraded in hypoxia in mouse cell lines and suggest that the degradation of SMARCB1 in inner renal medullary cells is a physiological response to the extreme hypoxic conditions of the inner medulla of the kidney. Although the reduction of SMARCB1 protein levels may physiologically protect renal cells from the hypoxic conditions of the renal medulla, our findings demonstrated that the sickling of red blood cells could exacerbate and prolong this hypoxia in the renal medulla (Fig. 1). This prolonged hypoxia thus broadens the window of opportunity for advantageous somatic mutations to arise and expand (25). Consequentially, the complete loss of a powerful tumor suppressor like SMARCB1 can contribute to driving tumorigenesis. Indeed, we found that the loss of SMARCB1 conferred a survival advantage to renal cell carcinoma cells under hypoxic conditions. To further support this notion, our study demonstrated that, compared to control mice, SCT mice develop relatively more aggressive renal tumors as a consequence of SMARCB1 degradation in response to the extreme hypoxia caused by sickling red blood cells (Fig. 6). Our findings may help explain why SMARCB1 loss is a consistent hallmark of all RMC cases that occur under the setting of SCT (1, 26).

These findings suggest that the protective effect of SMARCB1 loss under hypoxia enables the resistance of RMC to the antiangiogenic therapies used for treating other renal cell carcinomas (1, 5). In subcutaneous transplant mouse models with RMC219-tet-inducible SMARCB1, the reconstitution of SMARCB1WT, but not SMARCB1Null, increased the sensitivity of RMC219 tumors to the anti-angiogenic TKI, axitinib (Fig. 7). Additionally, we demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo that the tumorigenicity of renal tumor cells significantly increases with SMARCB1 protein loss in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4 and 5). These insights into the distinctly protective effects of SMARCB1 loss under hypoxia can guide the development of therapeutic strategies that prioritize targeting of other pathways in RMC (27).

SMARCB1 is a core subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex and our results are consistent with an emerging body of literature describing the role of the SWI/SNF complex in cellular hypoxia response (28–31). The SWI/SNF complex can directly regulate the expression of HIF1 and HIF2 target genes (27, 28), and its nuclear localization is subjected to oxygen regulation which may influence the expression of SWI/SNF target gene pathways (29). Furthermore, SMARCB1 can promote the ubiquitination and degradation of the nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 3 (NR4A3), which is a mediator of pro-survival pathways under hypoxic conditions (30), suggesting that SMARCB1 loss is prosurvival in hypoxia. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms via which SMARCB1 degradation, and its subsequent effect on pathways regulated by the SWI/SNF complex, can protect cells from hypoxic stress.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate a delicately balanced scenario in which SMARCB1 degradation lends a protective function in renal cells under the hypoxic microenvironment of the inner renal medulla, but the absence of this tumor suppressor within the prolonged extreme hypoxic environment induced by sickling red blood cells enables the tumorigenesis of RMC. Our study, therefore, offers some clarity into the strong association between SCT and developing RMC as well as the widespread prevalence of SMARCB1 loss in RMC tumors. Further, our data suggest that the protective effect of SMARCB1 degradation on the survival of renal medullary cells under hypoxia may explain the resistance of SMARCB1-deficient tumors, such as RMC, to therapeutic agents targeting hypoxia pathways, and can thus provide some insight into developing more effective therapeutics against RMC.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model Studies.

Mouse strains.

The Townes model of SCT (hα/hα::βA/βS) was generated by Tim Townes’s laboratory and obtained through Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 013071) (32). The Cdh16-Cre strain was generated by Peter Igarashi’s laboratory and obtained through Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 012237). The Rosa26LSL-TdT was generated by Hongkui Zeng’s laboratory and obtained through the Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 007908) (33). Strains were kept in a mixed C57BL/6J and 129Sv/Jae background. The Rosa26-Cas9 knockin mouse was generated by Feng Zhang and purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 026179) (34). The strain was kept in a C57BL/6J pure background. NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. All animal studies and procedures were approved by the UTMDACC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In Vitro Studies.

Cell lines.

mIMCD-3 (mouse inner medulla collecting duct) mouse cell lines were purchased from ATCC.

RMC219-Tet-inducible SMARCB1 cell line: The tetracycline-inducible pIND20-fSNF5-HA vector (35) was kindly donated by Bernard E. Weissman. The pInducer20 empty backbone (36) was a gift from Stephen Elledge (Addgene plasmid # 44012). Lentivirus was generated in HEK-293T cells and used to generate stable tet-inducible cell lines as previously described (37). RMC219 (also called JHRCC219), a human tumor cell line that was established in a previous study (23), was infected with tetracycline-inducible pIND20-fSNF5-HA vector. Cells were treated with 2 μg DOX for 3 d to reconstitute SMARCB1 (SNF5).

MSRT1 (Melinda Soeung renal tumor 1) was generated using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology as described in SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3 and Supporting methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant to MDACC (grant P30 CA016672) from the National Cancer Institute, by MD Anderson's Prometheus informatics system and by the Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology's Eckstein Laboratory. Dr. Pavlos Msaouel was supported by a Career Development Award by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, a Research Award by KCCure, the MD Anderson Khalifa Scholar Award, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation Fellowship, a Translational Research Partnership Award (KC200096P1) by the United States Department of Defense, an Advanced Discovery Award by the Kidney Cancer Association, the MD Anderson Physician-Scientist Award, and philanthropic donations by Mike and Mary Allen. We thank David W. Dwyer and Dr. Karen C. Dwyer at Advanced Cytometry & Sorting Facility at South Campus (NCI P30CA016672) for supporting flow cytometry data analysis, UTMDACC. We thank the Department of Veterinary Medicine & Surgery, UTMDACC. We thank Lucinette Marasigan for her valuable support in animal experiments, and the MDACC Small Animals Imaging Facility for their constant expert assistance in animal imaging. We would particularly like to thank Dr. Chieh-Yuan (Alex) Li, Dr. Jintan Liu, and Dr. Hideo Tomihara for sharing their valuable insight during the early conception of this work. Also, thank you to Dr. Dadi Jiang and Dr. Youming Guo for allowing us to use their hypoxia chamber for in vitro cell culture experiments during the revision of this manuscript. Biorender was used to generate some of the schematics.

Author contributions

M.S., Z.C., E.D., I.-L.H., F.C., M.D.P., D.D.S., C.L.W., A.C., A.V., N.M.T., G.F.D., P.M., and G.G. designed research; M.S., L.P., Z.C., E.D., I.-L.H., F.C., H.K., C.N.L., C.Z., S.J., N.M.Z., and R.M. performed research; M.D.P., N.F., S.J., N.M.Z., R.M., D.D.S., E.H.C., A.C., V.G., T.P.H., N.M.T., G.F.D., P.M., and G.G. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; M.S., L.P., E.D., L.Z., and P.M. analyzed data; D.L. contributed to writing and reviewing the final manuscript; and M.S., A.K.D., S.G., D.L., A.V., P.M., and G.G. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

Pavlos Msaouel has received honoraria for service on a Scientific Advisory Board for Mirati Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Exelixis; consulting for Axiom Healthcare Strategies; non-branded educational programs supported by Exelixis and Pfizer; and research funding for clinical trials from Takeda, Bristol Myers Squibb, Mirati Therapeutics, Gateway for Cancer Research, and UT MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Melinda Soeung, Email: MSoeung@mdanderson.org.

Pavlos Msaouel, Email: PMsaouel@mdanderson.org.

Giannicola Genovese, Email: GGenovese@mdanderson.org.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Msaouel P., et al. , Updated recommendations on the diagnosis, management, and clinical trial eligibility criteria for patients with renal medullary carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 17, 1–6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Msaouel P., Tannir N. M., Walker C. L., A model linking sickle cell hemoglobinopathies and SMARCB1 loss in renal medullary carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 2044–2049 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Msaouel P., et al. , Comprehensive molecular characterization identifies distinct genomic and immune hallmarks of renal medullary carcinoma. Cancer Cell 37, 720–734.e713 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Msaouel P., et al. , Comprehensive molecular characterization identifies distinct genomic and immune hallmarks of renal medullary carcinoma. Cancer Cell 37, 720–734. e13 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoumpourlis P., Genovese G., Tannir N. M., Msaouel P., Systemic therapies for the management of non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma: What works, what doesn’t, and what the future holds. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 19, 103–116 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez O., Rodriguez M. M., Jordan L., Sarnaik S., Renal medullary carcinoma and sickle cell trait: A systematic review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 62, 1694–1699 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro D. D., et al. , Association of high-intensity exercise with renal medullary carcinoma in individuals with sickle cell trait: Clinical observations and experimental animal studies. Cancers 13, 6022 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauchman M. I., Nigam S. K., Delpire E., Gullans S. R., An osmotically tolerant inner medullary collecting duct cell line from an SV40 transgenic mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 265, F416–424 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu X., Chaudhury A., Higgins J. M., Wood D. K., Oxygen-dependent flow of sickle trait blood as an in vitro therapeutic benchmark for sickle cell disease treatments. Am. J. Hematol. 93, 1227–1235 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum J. I., Bijli K. M., Murphy T. C., Kleinhenz J. M., Hart C. M., Time-dependent PPARγ modulation of HIF-1α signaling in hypoxic pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Med. Sci. 352, 71–79 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akimov V., et al. , UbiSite approach for comprehensive mapping of lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 631–640 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose C. M., et al. , Highly multiplexed quantitative mass spectrometry analysis of ubiquitylomes. Cell Syst. 3, 395–403.e4 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stukalov A., et al. , Multilevel proteomics reveals host perturbations by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Nature 594, 246–252 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarraf S. A., et al. , Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature 496, 372–376 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stes E., et al. , A COFRADIC protocol to study protein ubiquitination. J. Proteome Res. 13, 3107–3113 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Povlsen L. K., et al. , Systems-wide analysis of ubiquitylation dynamics reveals a key role for PAF15 ubiquitylation in DNA-damage bypass. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1089–1098 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li W., et al. , Integrative analysis of proteome and ubiquitylome reveals unique features of lysosomal and endocytic pathways in gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells. Proteomics 18, e1700388 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner S. A., et al. , A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 10, M111.013284 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Udeshi N. D., et al. , Methods for quantification of in vivo changes in protein ubiquitination following proteasome and deubiquitinase inhibition. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 11, 148–159 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zehir A., et al. , Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 23, 703–713 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tate J. G., et al. , COSMIC: The catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D941–D947 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He S., et al. , Structure of nucleosome-bound human BAF complex. Science. 367, 875–881 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong Y., et al. , Tumor xenografts of human clear cell renal cell carcinoma but not corresponding cell lines recapitulate clinical response to sunitinib: Feasibility of using biopsy samples. Eur. Urol. Focus 3, 590–598 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah A. Y., et al. , Management and outcomes of patients with renal medullary carcinoma: A multicentre collaborative study. BJU Int. 120, 782–792 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Y., et al. , Selection of metastasis competent subclones in the tumour interior. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1033–1045 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleming S., Distal nephron neoplasms. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 32, 114–123 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Msaouel P., Carugo A., Genovese G., Targeting proteostasis and autophagy in SMARCB1-deficient malignancies: Where next? Oncotarget 10, 3979–3981 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenneth N. S., Mudie S., van Uden P., Rocha S., SWI/SNF regulates the cellular response to hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4123–4131 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sena J. A., Wang L., Hu C. J., BRG1 and BRM chromatin-remodeling complexes regulate the hypoxia response by acting as coactivators for a subset of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor target genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 3849–3863 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dastidar R. G., et al. , The nuclear localization of SWI/SNF proteins is subjected to oxygen regulation. Cell Biosci. 2, 30 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu B., et al. , SMARCB1 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of NR4A3 via direct interaction driven by ROS in vascular endothelial cell injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2048210 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu L. C., et al. , Correction of sickle cell disease by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Blood 108, 1183–1188 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madisen L., et al. , A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cortez J. T., et al. , CRISPR screen in regulatory T cells reveals modulators of Foxp3. Nature 582, 416–420 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei D., et al. , SNF5/INI1 deficiency redefines chromatin remodeling complex composition during tumor development. Mol. Cancer Res. 12, 1574–1585 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meerbrey K. L., et al. , The pINDUCER lentiviral toolkit for inducible RNA interference in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3665–3670 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu K., Ma H., McCown T. J., Verma I. M., Kafri T., Generation of a stable cell line producing high-titer self-inactivating lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 3, 97–104 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.