Abstract

EXecutive-functions Innovative Tool 360° (EXIT 360°) is an original 360° instrument for an ecologically valid and multicomponent evaluation of executive functioning. This work aimed to test the diagnostic efficacy of EXIT 360° in distinguishing executive functioning between healthy controls (HC) and patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PwPD), a neurodegenerative disease in which executive dysfunction is the best-defined cognitive impairment in the early stage. 36 PwPD and 44 HC underwent a one-session evaluation that involved (1) neuropsychological evaluation of executive functionality using traditional paper-and-pencil tests, (2) EXIT 360° session and (3) usability assessment. Our findings revealed that PwPD made significantly more errors in completing EXIT 360° and took longer to conclude the test. A significant correlation appeared between neuropsychological tests and EXIT 360° scores, supporting a good convergent validity. Classification analysis indicated the potential of the EXIT 360° for distinguishing between PwPD and HC in terms of executive functioning. Moreover, indices from EXIT 360° showed higher diagnostic accuracy in predicting PD group membership compared to traditional neuropsychological tests. Interestingly, EXIT 360° performance was not affected by technological usability issues. Overall, this study offers evidence that EXIT 360° can be considered an ecological tool highly sensitive to detect subtle executive deficits in PwPD since the initial phases of the disease.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Cognitive ageing, Cognitive neuroscience, Computational neuroscience, Diseases of the nervous system, Neurological disorders, Neurological disorders

Introduction

Virtual reality-based (VR) evaluation can be considered a new promising paradigm for neuropsychological assessment, able to provide an ecological evaluation of everyday cognitive impairments predicting real-world performance1, compared to traditional paper-and-pencil or computerized neuropsychological batteries2. In the last few years, advances in 360° technology emerged as an interesting alternative approach to create VR content by recording familiar environments before, and then showing them to participants on a head-mounted display (HMD)3,4. Furthermore, 360° settings allow participants to be evaluated in virtual scenarios that they experience from a first-person perspective, overcoming some technical (e.g., high skills or cost) and clinical (e.g., vertigo, nausea) limitations of VR1,5. Borgnis and colleagues (2021) have developed EXecutive-functions Innovative Tool 360° (EXIT 360°), an original 360° instrument for an ecologically valid and multicomponent evaluation of executive functioning6. Participants are engaged in a “game for health” in which they are immersed in 360° household environments delivered via a conventional HDM. In these scenarios, subjects have to complete seven everyday subtasks designed to assess several aspects of executive functioning simultaneously and quickly. The need to develop EXIT 360° arose from the literature that showed the inability of traditional neuropsychological tests to detect executive impairments in everyday situations7,8. However, executive dysfunction constitutes a significant public health challenge in several psychiatric and neurological pathologies due to their high impact on personal independence (e.g., preparing meals, managing money, shopping, using a telephone), ability to work, educational success and social relationships8–10. Consequently, its ecologically valid assessment must be early and adequate to plan timely rehabilitation interventions11,12. Over the years, several studies have shown the feasibility and acceptability of VR-based tools in the early assessment of executive functioning in healthy controls and many psychiatric and neurologic pathologies (see review13). However, a recent systematic review (2022) has shown several psychometric issues in the available VR-based assessment tools for executive functioning due to limited studies on construct validity, discriminant validity, usability, and test re-test reliability13.

To date, EXIT 360° appears to be an innovative and interesting solution within the field of neuropsychological evaluation of executive functionality since preliminary studies involving healthy control subjects showed excellent results in construct validity14 and usability15,16. Firstly, EXIT 360° can be considered a usable, learn-to-use, clear, enjoyable, attractive, and friendly assessment tool, regardless of demographic characteristics (age and education) or technological expertise. Moreover, it appeared to be a fast, original, engaging, and challenging tool able to evaluate real-life impairments in several components of executive functioning (e.g., planning, decision-making, problem-solving, attention, visual searching, and working memory) with irrelevant adverse effects.

In light of these characteristics and psychometric proprieties, EXIT 360° could represent a promising tool for evaluating executive dysfunctions in several clinical populations, such as Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Indeed, in addition to the well-documented motor symptoms (e.g., bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity), people with PD frequently develop a wide range of non-motor symptoms (NMS) since the initial stages of the disease course, even before the onset of motor symptoms in the prodromal state17–19. Cognitive dysfunction represents one of the major clinical NMS of PD17, and executive dysfunction is the best-defined cognitive impairment in early-stage non-demented PD20, particularly affecting attention, planning, deduction, inhibition, capacity to elaborate a strategy, set-shifting (flexibility) and working memory21. As a result, patients have trouble in many goal-directed everyday activities, with negative implications for daily functioning (i.e., preparing meals, managing money, shopping, and work)12,22,23 and quality of life23–25. Interestingly, an increasing number of longitudinal studies suggested that early executive dysfunction is predictive of PD conversion in “PD with dementia”26,27. However, some studies showed that traditional standard assessment appeared not sensitive to the early detection of executive deficits22. Therefore, EXIT 360° could permit early detection of executive deficits and, consequently, identify patients at risk of developing dementia, providing early neurorehabilitative interventions22,28.

This study wants to deepen EXIT 360° diagnostic efficacy in distinguishing executive functionality between healthy subjects and patients with PD, also compared with traditional neuropsychological tests for executive functioning. It should be noted that the lack of discriminant validity constitutes a significant limitation in the use of a specific tool since the absence of information on diagnostic specificity and sensitivity in clinical populations makes it impossible to introduce them into clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Recruited sample

Thirty-six patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PwPD group) and 44 healthy controls (HC group) have been involved in this study. PwPD were consecutively recruited by an experienced neurologist at the Parkinson Center of IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi ONLUS (FDG, Milan, Italy). HC were recruited among volunteers, family members and people participating in the public meeting. All participants have met the inclusion criteria: (a) Age between 18 and 90 years (b) education ≥ 5; (c) absence of overt dementia as determined by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test29 (MoCA score ≥ 15.51, cut-off of normality), corrected for age and years of education according to Italian normative data30; (d) ability to provide written, signed informed consent. In addition, patients have met the following inclusion criteria: a) clinically established or probable Parkinson’s disease according to Movement Disorder Society (MDS)31; (b) mild to moderate disease staging, with scores < 3 on the Hoehn and Yahr scale; (c) suspected or confirmed deficits linked to executive functioning confirmed by documented neurological and/or neuropsychological evaluation. Exclusion criteria included (a) severe hearing or visual impairment that could compromise the assessment with EXIT 360°; (b) major systemic, psychiatric, or other neurological illnesses; (c) visual hallucinations or vertigo.

The study was approved by the “Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi-Milan” Ethics Committee. The neuropsychologist provided all participants with a complete explanation of the purpose and risk of the study before they signed the written informed consent based on the revised Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

All participants underwent a one-session evaluation at FDG that involved three main phases: (a) neuropsychological evaluation, (b) EXIT 360° session, and (c) usability assessment32.

Neuropsychological evaluation

All subjects performed, in a clinical setting and before EXIT 360° completion, a neuropsychological evaluation of global and executive functioning, conducted by a trained neuropsychologist using conventional pencil–paper tests:

-

[a]

Montreal cognitive assessment test (MoCA): a sensitive screening tool able to exclude the presence of global cognitive impairment.

-

[b]

Integrated executive functions battery involving Trail Making Test33, phonemic verbal fluency task (F.A.S.)34, Stroop Test35, Digit Span Backward36, Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB)37,38, Attentive Matrices39 and Progressive Matrices of Raven (PMR)40,41 (for a detailed description of administered neuropsychological tests see32).

EXIT 360° session

Each subject underwent an evaluation with EXIT 360°, preceded by a familiarization phase with the device and virtual environment to control any adverse effects (e.g., dizziness, nausea). Detailed characteristics and administration procedure of EXIT 360° have been recently described in a published study protocol32. Briefly, EXIT 360° is a 360°-based assessment tool for a complete assessment of executive functioning, engaging participants in a “game for health” delivered via smartphones, in which they have to perform seven subtasks (e.g., Unlock the Door; Choose the Person; Turn on the light) in 360° domestic environments (e.g., living room and bedroom). All participants sit on a swivel chair and wear the mobile-powered headset that allows for immersing in virtual environments explorable through the head’s movement as in real-life situations42. The test started when they heard, “You are about to enter a house. Your goal is to get out of this house in the shortest time possible. To exit, you will have to complete a path and a series of tasks that you will encounter along your way. Are you ready to start?”. To respond to each task, subjects had to choose between three or more alternatives by moving their head and positioning a small white dot that they saw in the headset on the answer for a few seconds. Participants had to perform all seven subtasks, obtaining one point for a wrong answer or two for a correct one. Overall, EXIT 360° allowed for the collection of Total Score (range 7–14) and Total Reaction Time (i.e., time spent to solve each of the 7 tasks, excluding instructions time. Then, the Total Reaction Time of EXIT 360° was calculated by summing the single reaction times).

Usability assessment

All participants underwent a usability assessment of the technological tool using the System Usability Scale (SUS), a short questionnaire of 10 items on a 5-point scale from “completely disagree” to “strongly agree”43,44.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included the frequencies, percentages, median and interquartile range (IQR) for categorical variables and the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous ones. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the two groups (i.e., PD and HC) were compared using a t-test for independent samples (parametric or non-according to variables) or a chi-squared test for categorical variables. Moreover, ANOVA one-way between subjects was conducted to assess any differences between groups in traditional neuropsychological tests and EXIT 360° scores. Pearson’s correlation was applied to evaluate the possible relationship between the scores of the conventional neuropsychological tests and EXIT 360° scores (Total Score and Total Time). Finally, ROC curves evaluated all the tests’ specificity and sensitivity. Regarding system usability, Pearson’s correlation was conducted to compare EXIT 360° scores with the usability score. Moreover, ANOVA between subjects was performed to evaluate any differences in usability between the two groups. All statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi 1.6.7. Corrections for multiple comparisons were performed using the online calculator of False discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons. A p-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Nonlinear stochastic approximation (i.e., machine learning) methods were used to compare the classification accuracy of traditional neuropsychological assessments versus the EXIT 360° indices for classifying participants into either the “Patients with PD” or “Healthy Controls” groups. Different machine learning algorithms were employed: Logistic Regression and Support Vector Machine algorithms. All these analyses were computed using Python 3.4.

Finally, we conducted an additional analysis dividing the PD sample into two groups according to performance on traditional neuropsychological (NPS) tests for executive functioning: Group PD_NPS + (i.e., patients with pathological/borderline performance in at least one NPS test) and Group PD_NPS- (i.e., patients that reported deficits in everyday activities linked to executive functioning—e.g., managing money or cooking—with a normal performance at NPS). We performed ANOVA between groups (PD_NPS + ; PD_NPI-; HC) to show any difference between the three groups in EXIT 360° and NPS scores. The results were reported in supplementary materials.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by “Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi—Milan” Ethics Committee.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Results

Participants

Table 1 reports the demographic and clinical characteristics of the whole sample (N = 80), divided into two groups (PwPD and HC). PwPD (n = 36) were predominantly female (M:F = 15:21) with a mean age of 68.7 (SD = 8.22, range = 53–84) and age of education = 13 (IQR = 6, range 5–18); HC were predominantly female (M:F = 18:26) with a mean age of 65.5 (SD = 13.8, range = 40–89) and age of education = 13 (IQR = 8.50, range 5–18). No significant differences between the two groups were detected in demographic characteristics and the global cognitive level assessed with the MoCA test. Moreover, all participants showed no cognitive impairment (MoCA score ≥ 15.51).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the whole sample.

| PwPD N = 36 | HC N = 44 | Group comparison (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean (SD)) | 68.7 (8.22) | 65.5 (13.8) | .224 |

| Sex (M: F) | 15:21 | 18:26 | .945 |

| Age of education (years, median (IRQ)) | 13 (6) | 13 (8.50) | .726 |

| MoCA_adjusted score (mean (SD)) | 25.8 (2.41) | 24.7 (2.72) | .082 |

M Male, F Female, SD Standard deviation, IQR Interquartile range, n Number, MoCA Montreal cognitive assessment, PwPD Patients with Parkinson’s Disease, HC Healthy controls.

Traditional neuropsychological evaluation

Table 2 shows significant differences between the two groups in four neuropsychological tests of executive functioning. Specifically, HC achieved higher performance compared to PwPD in FAB score (F (1,78) = 27.81; p < .001) and PMR (F (1,78) = 7.82; p = .007). Moreover, HC group obtains better results compared to PwPD, in TMT-B (F (1,78) = 4.70; p = .033) and TMT-BA (F (1,78) = 5.32; p = .024). However, corrections for multiple comparisons showed the absence of differences between HC and PwPD in TMT-B (corrected p-value = .083) and TMT-BA (corrected p-value = .08).

Table 2.

Comparison of scores at traditional neuropsychological tests.

| PwPD mean (SD) | HC mean (SD) | Group comparison (p-value) | Corrected p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trail making test—A | 32.68 (16.64) | 30.59 (21.91) | .641 | .801 |

| Trail making test—B | 117.28 (105.94) | 78.52 (48.32) | .033 | .083 |

| Trail making test—B–A | 85.5 (98.11) | 49 (34.03) | .024 | .08 |

| Verbal fluency | 37.81 (11.55) | 38 (9.68) | .936 | .936 |

| Stroop test—errors | 0.81 (3.1) | 0.45 (0.76) | .463 | .661 |

| Stroop test—time | 19.58 (13.15) | 22.77 (13.41) | .289 | .482 |

| Digit span backward | 4.47 (1.09) | 4.52 (1.03) | .826 | .918 |

| Frontal assessment battery | 15.71 (1.98) | 17.52 (1.03) | < .001 | .001 |

| Attentive matrices | 47.68 (7.44) | 50.34 (6.57) | .094 | .188 |

| Progressive matrices of Raven | 30.37 (4.04) | 32.49 (2.73) | .007 | .035 |

SD Standard deviation, PwPD Patients with Parkinson’s Disease, HC Healthy controls.

In bold, statistically significant value.

EXIT 360°

Table 3 shows significant differences between the two groups in Total EXIT score (F (1,78) = 70.8; p < .001; η2p = .476) and Total Reaction time (F (1,78) = 52.8; p < .001; η2p = .404). Specifically, the HC group obtained a higher Total score compared to PwPD (mean = 12.5 ± 0.95) and completed the test in less time (mean = 484 ± 133.30).

Table 3.

Comparison of scores at EXIT 360°.

| PwPD Mean (SD) | HC Mean (SD) | Group comparison (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total EXIT score | 10.2 ± 1.46 | 12.5 ± 0.95 | < .001 |

| Total reaction time | 717.4 ± 153.98 | 484 ± 133.30 | < .001 |

SD Standard deviation, PwPD Patients with Parkinson’s Disease, HC Healthy controls.

In bold, statistically significant value.

Correlation between neuropsychological tests and EXIT 360°

Table 4 shows significant correlations (Pearson’s correlation) between traditional paper and pencil neuropsychological tests and the two scores of EXIT 360°.

Table 4.

Correlation between EXIT 360° scores and neuropsychological assessment.

| PMR | AM | FAB | VF | DS | TMT-A | TMT-B | TMT-BA | ST-E | ST-T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXIT-360° Total Score | .464** | .271** | .620** | .305* | .232* | − .309* | − .453** | − .424** | − .251* | − .218 |

| EXIT-360° Total Time | − .333* | − .209 | − .433** | − .084 | − .009 | .170 | .477** | .489** | .199 | .139 |

PMR Progressive matrices of raven, AM Attentive matrices, FAB Frontal assessment battery, VF Verbal fluency, DS Digit span, TMT-A Trail making test-part A, TMT-B Trail making test-part B, TMT-BA Trail making test-part B–A, ST-E Stroop test-errors, ST-T Stroop test-time.

In bold, statistically significant scores.

*p < .05; **p < .001.

Classification of healthy controls or clinical group

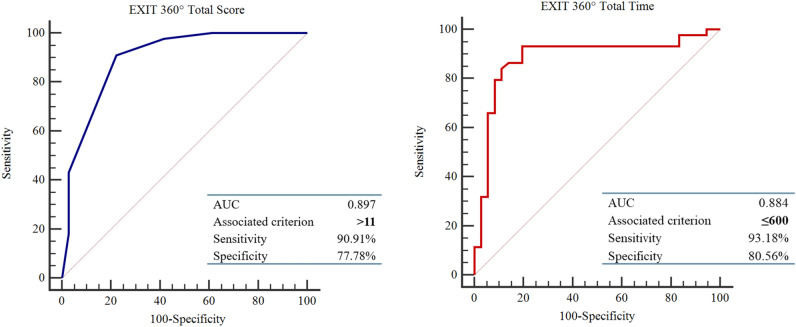

The performance of the classifiers was evaluated by carrying out a relative operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) provides a single measure of overall prediction accuracy. Specifically, ROC curves investigated the diagnostic accuracy of EXIT 360° showing that (Fig. 1):

EXIT Total Score ≤ 11 could accurately discriminate HC and PwPD groups, with high sensitivity (90.91%) and specificity (77.78%) (AUC = 0.897—excellent accuracy value).

EXIT Total Time > 600 could accurately discriminate HC and PwPD groups, with high sensitivity (93.18%) and specificity (80.56%) (AUC = 0.884—excellent accuracy value).

Figure 1.

ROC Curve—EXIT 360° Total Time and Total Score.

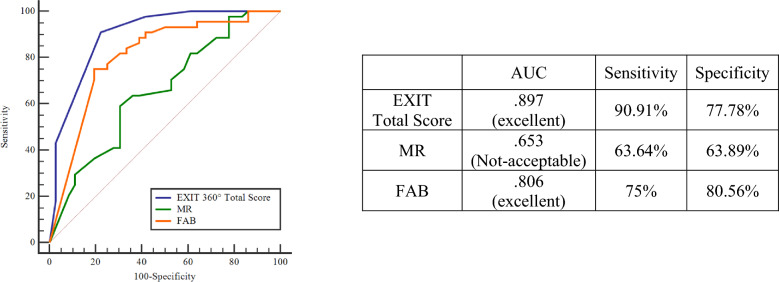

Further analyses showed EXIT Total Score ≤ 11 can discriminate between HC and PwPD with better overall prediction accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity than MR (DeLong test—p < .001) and FAB (DeLong test—p = .04) scores (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

ROC Curve—Comparison between EXIT 360° Total Score and neuropsychological tests. MR Raven’s progressive matrices, FAB Frontal assessment battery.

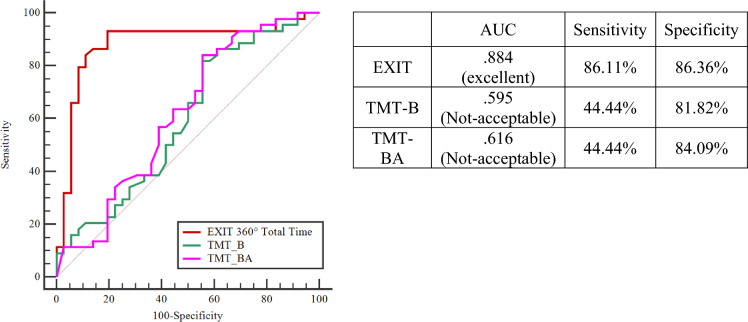

Moreover, EXIT Total Time > 600 allows for discriminating between HC and PwPD with better overall prediction accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity than TMT-B and TMT-BA (DeLong test—p < .001) scores (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

ROC Curve—Comparison between EXIT 360° Total Time Score and neuropsychological tests. TMT Trail making test.

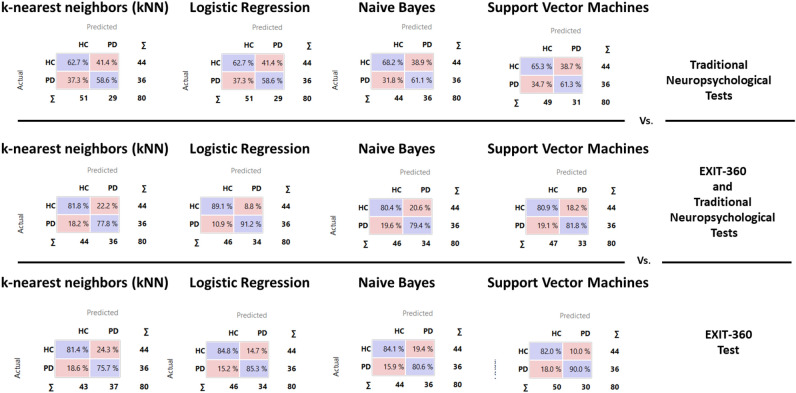

In addition, nonlinear stochastic approximation methods confirmed the ROC analyses, showing an excellent accuracy of EXIT 360° scores in discriminating HC and PwPD. Results showed a precision (i.e., the proportion of true positives among all the instances classified as positive) between 61 and 65% for the conventional neuropsychological assessment of executive functions (Table 5 panel A), while it ranged from 79 to 86% for EXIT 360° (Table 5 panel C) and from 80 to 90% for traditional battery and EXIT 360° together (Table 5 panel B).

Table 5.

Leave one out cross-validation (LOOCV) for the traditional neuropsychological tests [A], the indices of EXIT-360° and the traditional neuropsychological tests [B], and the indices of EXIT-360° [C].

| Methods | AUC | CA | F1 | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [A] Traditional neuropsychological tests | |||||

| k-nearest neighbors (kNN) | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Logistic regression | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| Naive bayes | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Support vector machine (SVM) | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.64 |

| [B] EXIT-360° and Traditional Neuropsychological tests | |||||

| k-nearest neighbors (kNN) | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Logistic regression | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Naive bayes | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Support vector machine (SVM) | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| [C] EXIT-360° | |||||

| k-nearest neighbors (kNN) | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Logistic regression | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Naive bayes | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Support vector machine (SVM) | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.85 |

AUC (Area under the ROC curve) is the area under the classic receiver-operating curve; CA (Classification accuracy) represents the proportion of the examples that were classified correctly; F1 represents the weighted harmonic average of the precision and recall (defined below); Precision represents a proportion of true positives among all the instances classified as positive. In our case, the proportion of conditions correctly identified; Recall represents the proportion of true positives among the positive instances in our data.

Interestingly, all machine learning algorithms showed that the indices from EXIT 360° had a higher capability in predicting PD Group membership compared to traditional neuropsychological tests of executive functioning (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Classification of HC or PwPD. The diagonal values (i.e., purple boxes) represent the elements for which the predicted group is equal to the true group, while of-diagonal elements are those that are mislabeled by the classifier. Logistic Regression and Support Vector Machine algorithms demonstrated that EXIT-360° has a higher capability in predicting PD Group membership with respect to traditional neuropsychological tests of executive functioning.

Usability

The comparison between the PwPD and HC showed the absence of a significant difference in usability score (F (1,78) = .415; p = .521). Indeed, PwPD provided a mean score of 77.3 ± 9.30, while HC showed a mean score of 75.7 ± 12.41. Both scores indicate a satisfactory level of usability, according to the scale’s score acceptability ranges (cut off = 68) and adjective ratings (included between “good” and “excellent”). Moreover, Pearson’s correlation showed no significant relationship between the total usability score and, respectively, EXIT 360° Total score (p = .711) and EXIT 360° Time score (p = .560).

Discussion

This work aimed to determine whether EXIT 360° could integrate the conventional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological assessment in PD, providing a more ecologically valid evaluation of executive functions. Firstly, we examined the performance of PwPD and HC by comparing the traditional neuropsychological battery with the EXIT 360° to evaluate its efficacy in detecting executive deficits. Correlations between performances on EXIT 360° and paper-and-pencil tests were also investigated. Finally, we looked into the predictive validity of EXIT 360° scores in discriminating PwPD from HC in executive functioning. All subjects were in a relatively well-preserved clinical state. However, the neuropsychological assessment of executive functions showed differences between patients and HC in two tests (FAB and PMR). Correlation analyses indicated that neuropsychological tests correlate significantly with EXIT 360° scores, supporting a good convergent validity14. Therefore, EXIT 360° can be considered a tool able to detect several components of executive functioning, including cognitive flexibility, inhibition control, sustained and selective attention and processing speed.

As regards analyses on EXIT 360°, our main findings revealed significantly different performances between patients and cognitively healthy participants in both EXIT 360° scores. Specifically, PD patients, compared with HC, made more errors in completing the subtasks of EXIT 360° and took longer to conclude the test (i.e., a slower processing speed). These results showed that EXIT 360° is an ecological tool highly sensitive to executive impairment in PD since the mild-to-moderate stage of PD (Hoehn e Yahr scores < 3) when motor symptoms outweigh the cognitive ones. This assumes considerable importance in clinical practice since executive deficits in the early stage of PD are predictive of the conversion to dementia20,45–47, with a negative impact on everyday functioning8,24,25. Therefore, identifying patients with a potentially higher risk of dementia appears to be a priority to plan an early and individualized cognitive rehabilitation treatment22,28.

Interestingly, our results align with a previous study on PwPD that showed the efficacy of a VR-based instrument, VMET, in evaluating executive impairments, which had not been fully acknowledged by traditional neuropsychological evaluations22. It is well known that the most crucial issues of the traditional neuropsychological tests are the lack of ecological validity and the ability to measure only one specific component of executive functions without reflecting an accurate and complex picture of a patient’s executive status7,8,48. For this reason, patients with presumed executive deficits can perform similarly to HC on traditional neuropsychological tests yet encountering difficulties in real-world situations22. In this context, the technology 360° may be used to offer a new paradigm in which patients are active participants within an ecological virtual world1,49 in which it is possible to simulate life-like challenges that reproduce everyday situations. In this framework, EXIT 360° has proved to be an innovative tool for detecting executive dysfunction through a function-led approach that combined experimental control with an engaging real-world background.

In addition, results obtained from ROC curve analyses clearly indicated the potential of EXIT 360° scores (accuracy and completion time) in distinguishing between PwPD and HC in terms of executive functioning. Specifically, a total score of ≤ 11 allows for accurate (AUC = .897) discrimination of PwPD compared to HC with high sensitivity and specificity. The same results appear considering the total time score, where a value > 600 allows for accurately (AUC = .884) discriminating between patients and controls in terms of processing speed. Moreover, ROC curve analyses allowed us to demonstrate the ability of EXIT 360° Total Score and EXIT 360° Time Score to discriminate between HC and PwPD with better overall prediction accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity than traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological assessment for executive functioning. Conventional neuropsychological tests, such as FAB, are stronger tools when the cognitive deficit is overt. In line with the previous evidence, EXIT 360° would be a tool more sensible in the early stage of executive impairments since it collected some ecological aspects that impact everyday functioning22,50,51.

These findings were also confirmed by the higher diagnostic accuracy in machine learning classification of participants to the clinical or non-clinical conditions (when using indices from EXIT 360°) with respect to those from neuropsychological assessments. These robust findings demonstrated the efficacy of EXIT 360° for detecting impairment of several components of executive functioning at an early clinical stage of PD. Therefore, EXIT 360° can be considered an ecological tool highly usable for prompt diagnosis of executive dysfunction and early enrolment of patients in targeted rehabilitation.

Interestingly, machine learning analyses have also suggested that integration between neuropsychological tests and EXIT 360° could allow better classification accuracy, with precision ranging between 80 and 90%. This result supported the potentiality of EXIT 360° to integrate the traditional neuropsychological assessment of EFs in PD with a more ecologically valid assessment.

Overall, our results confirm that the 360° technology may play a key role in neuropsychological assessment, in accordance with previous studies5. In particular, our findings follow previous evidence on the 360° version of the Picture Interpretation Test (PIT) ability to detect executive dysfunction in active visual perception, typical of PwPD compared to HC. EXIT 360° can be considered an evolution of the PIT 360°, allowing to evaluate several components of executive functioning in an ecological context. The multicomponent aspect appears critical in the clinical evaluation of PwPD since several studies have shown the presence of several executive impairments in PD, such as planning, attention, working memory, set-shifting, dual-task performance, inhibitory control, and decision making, including social–cognition abilities9,13,52,53. In addition, EXIT 360° reproduces everyday domestic settings, such as the kitchen, bedrooms, living room, and landing, allowing an evaluation of the executive impairments in the environment most experienced by the subject, with wide implications also in terms of rehabilitation. This feature is peculiar to EXIT 360° since all technological-based tools for evaluating executive functions in PD have involved only a few everyday life scenarios, especially supermarkets but never domestic environments13. Finally, in line with a previous study16, EXIT 360° obtained good to excellent usability score and the absence of correlation between total usability score and EXIT 360° indexes. Therefore, low performances of participants did not depend on technological usability.

While the current study’s findings are promising, some limitations and future perspectives should be considered. Firstly, to fully evaluate the potentiality of EXIT 360° as a new screening tool for executive functions, future studies are needed to assess its test–retest and inter-rater reliability. Additionally, although participants do not need to move in the environment, they must explore the environment by moving their heads; therefore, it cannot be excluded that EXIT 360° could involve other cognitive domains, such as motor representation and programming. Future studies should investigate this aspect by including measures of motor functioning in a regression analysis along with executive functions. Moreover, it will be important to investigate the value of EXIT 360° in detecting executive impairments in other neurological populations known to have executive dysfunctioning, such as Multiple Sclerosis, Mild Cognitive Impairments and Alzheimer’s Disease. Finally, it will be of fundamental importance to develop and validate a parallel form of EXIT 360° to make possible a short-term revaluation in a rehabilitation process.

In conclusion, this study offers evidence that a more ecologically valid evaluation of executive functions is more likely to detect subtle executive deficits in PD patients. EXIT 360° captures early executive dysfunctions of PwPD with better accuracy than the traditional neuropsychological assessment. In this context, we think EXIT 360° has a great potentiality in integrating the traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological assessment in PD, with a more ecologically valid assessment of executive functions. This innovative 360°-based instrument, easily accessible and clinically usable, can radically transform patients' and clinicians' assessment experience. Firstly, the times for evaluating executive functionality will be drastically reduced since EXIT 360° lasts at most 15 min. In addition, neurologists and neuropsychologists can get ecologically-valid multicomponent evaluations of executive functioning in PD, collecting the real executive status of patients. The ecological assessment will allow tailoring rehabilitation to the everyday subject’s needs. As previously said, a timely intervention on executive dysfunction in early-stage non-demented PD could minimize the impact of this significant clinical non-motor symptom, increasing the patient's daily functioning and quality of life20,21. Interestingly, as it was designed, EXIT 360° could also be used by a streaming platform that would allow to carry out the remote assessment, overcoming the social distancing limits.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

F.B. (Francesca Borgnis) and P.C. developed EXecutive-functions Innovative Tool 360°; F.B. (Francesca Borgnis), F.B. (Francesca Baglio), and P.C. conceived and designed the experiments. F.B. (Francesca Borgnis) and F.R. performed the experiment and collected data. F.B. (Francesca Borgnis), F.B. (Francesca Borghesi) and P.C. conducted the statistical analysis. M.M. recruited patients with Parkinson’s Disease. E.P. and F.R. supervised the methods and results. F.B. (Francesca Borgnis) wrote the first manuscript under the final supervision of F.B. (Francesca Baglio), P.C. and G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2022–2024).

Data availability

The tool and datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7006781.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-35530-9.

References

- 1.Parsons TD. Virtual reality for enhanced ecological validity and experimental control in the clinical, affective and social neurosciences. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015;9(DEC):1–19. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neguț A, Matu S-A, Sava FA, David D. Virtual reality measures in neuropsychological assessment: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016;30(2):165–184. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2016.1144793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Negro Cousa E, Brivio E, Serino S, Heboyan V, Riva G, de Leo G. New Frontiers for cognitive assessment: An exploratory study of the potentiality of 360 technologies for memory evaluation. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019;22(1):76–81. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ventura S, Brivio E, Riva G, Baños RM. Immersive versus non-immersive experience: Exploring the feasibility of memory assessment through 360 technology. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:2509. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serino S, Baglio F, Rossetto F, Realdon O, Cipresso P, Parsons TD, Cappellini G, Mantovani F, de Leo G, Nemni R, Riva G. Picture interpretation test (PIT) 360°: An innovative measure of executive functions. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16121-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgnis F, Baglio F, Pedroli E, Rossetto F, Riva G, Cipresso P. A simple and effective way to study executive functions by using 360° videos. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15(April):1–9. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.622095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgess PW, Alderman N, Forbes C, Costello A, Coates LMA, Dawson DR, Anderson ND, Gilbert SJ, Dumontheil I, Channon S. The case for the development and use of “ecologically valid” measures of executive function in experimental and clinical neuropsychology. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2006;12(2):194–209. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan RCK, Shum D, Toulopoulou T, Chen EYH. Assessment of executive functions: Review of instruments and identification of critical issues. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2008;23(2):201–216. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013;64:135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26(1):119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohil CJ, Alicea B, Biocca FA. Virtual reality in neuroscience research and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12(12):752–762. doi: 10.1038/nrn3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine B, Stuss DT, Winocur G, Binns MA, Fahy L, Mandic M, Bridges K, Robertson IH. Cognitive rehabilitation in the elderly: Effects on strategic behavior in relation to goal management. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc: JINS. 2007;13(1):143. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borgnis F, Baglio F, Pedroli E, Rossetto F, Uccellatore L, Oliveira JAG, Riva G, Cipresso P. Available virtual reality-based tools for executive functions: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2022;13:833136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borgnis F, Borghesi F, Rossetto F, Pedroli E, Lavorgna L, Riva G, Cipresso P. Psychometric calibration of a tool based on 360° videos for the assessment of executive functions. J. Clin. Med. 2023;12(4):1645. doi: 10.3390/jcm12041645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgnis F, Baglio F, Pedroli E, Rossetto F, Isernia S, Uccellatore L, Riva G, Cipresso P. EXecutive-functions innovative tool (EXIT 360°): A usability and user experience study of an original 360°-based assessment instrument. Sensors. 2021;21(17):5867. doi: 10.3390/s21175867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgnis F, Baglio F, Pedroli E, Rossetto F, Meloni M, Riva G, Cipresso P. A psychometric tool for evaluating executive functions in Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11(5):1153. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aarsland D, Zaccai J, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.: Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2005;20(10):1255–1263. doi: 10.1002/mds.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang, C., Lv, L., Mao, S., Dong, H., & Liu, B. (2020). Cognition deficits in parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms and treatment. Parkinson’s Disease, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Fengler S, Liepelt-Scarfone I, Brockmann K, Schäffer E, Berg D, Kalbe E. Cognitive changes in prodromal Parkinson’s disease: A review. Mov. Disord. 2017;32(12):1655–1666. doi: 10.1002/mds.27135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kudlicka A, Clare L, Hindle JV. Executive functions in Parkinson’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2011;26(13):2305–2315. doi: 10.1002/mds.23868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maggio MG, de Cola MC, Latella D, Maresca G, Finocchiaro C, la Rosa G, Cimino V, Sorbera C, Bramanti P, de Luca R. What about the role of virtual reality in Parkinson disease’s cognitive rehabilitation? Preliminary findings from a randomized clinical trial. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2018;31(6):312–318. doi: 10.1177/0891988718807973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cipresso P, Albani G, Serino S, Pedroli E, Pallavicini F, Mauro A, Riva G. Virtual multiple errands test (VMET): A virtual reality-based tool to detect early executive functions deficit in parkinson’s disease. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;8(DEC):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawson RA, Yarnall AJ, Duncan GW, Breen DP, Khoo TK, Williams-Gray CH, Barker RA, Collerton D, Taylor J-P, Burn DJ. Cognitive decline and quality of life in incident Parkinson’s disease: The role of attention. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016;27:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barone, P., Erro, R., & Picillo, M. (2017). Quality of life and nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. In International Review of Neurobiology (Vol. 133, pp. 499–516). Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Leroi I, McDonald K, Pantula H, Harbishettar V. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease: Impact on quality of life, disability, and caregiver burden. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(4):208–214. doi: 10.1177/0891988712464823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azuma T, Cruz RF, Bayles KA, Tomoeda CK, Montgomery EB., Jr A longitudinal study of neuropsychological change in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2003;18(11):1043–1049. doi: 10.1002/gps.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janvin CC, Aarsland D, Larsen JP. Cognitive predictors of dementia in Parkinson’s disease: A community-based, 4-year longitudinal study. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18(3):149–154. doi: 10.1177/0891988705277540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serino S, Pedroli E, Cipresso P, Pallavicini F, Albani G, Mauro A, Riva G. The role of virtual reality in neuropsychology: The virtual multiple errands test for the assessment of executive functions in Parkinson’s disease. Intell. Syst. Ref. Lib. 2014;68:257–274. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54816-1_14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santangelo G, Siciliano M, Pedone R, Vitale C, Falco F, Bisogno R, Siano P, Barone P, Grossi D, Santangelo F. Normative data for the montreal cognitive assessment in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 2015;36(4):585–591. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1995-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, Poewe W, Olanow CW, Oertel W, Obeso J, Marek K, Litvan I, Lang AE. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015;30(12):1591–1601. doi: 10.1002/mds.26424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borgnis F, Baglio F, Pedroli E, Rossetto F, Meloni M, Riva G, Cipresso P. EXIT 360: Executive-functions innovative tool 360—a simple and effective way to study executive functions in parkinson’s disease by using 360 videos. Appl. Sci. 2021;11(15):6791. doi: 10.3390/app11156791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reitan RM. Trail Making Test. Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novelli G, Papagno C, Capitani E, Laiacona M. Tre test clinici di memoria verbale a lungo termine: Taratura su soggetti normali. Arch. Psicol. Neurol. Psichiatr. 1986;47(2):278–296. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935;18(6):643. doi: 10.1037/h0054651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monaco M, Costa A, Caltagirone C, Carlesimo GA. Forward and backward span for verbal and visuo-spatial data: Standardization and normative data from an Italian adult population. Neurol. Sci. 2013;34(5):749–754. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Appollonio I, Leone M, Isella V, Piamarta F, Consoli T, Villa ML, Forapani E, Russo A, Nichelli P. The frontal assessment battery (FAB): Normative values in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 2005;26(2):108–116. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: A frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55(11):1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spinnler H, Tognoni G. Standardizzazione e taratura italiana di tests neuropsicologici. [Italian normative values and standardization of neuropsychological tests] Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1987;6(8):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caffarra P, Vezzadini G, Zonato F, Copelli S, Venneri A. A normative study of a shorter version of Raven’s progressive matrices 1938. Neurol. Sci. 2003;24(5):336–339. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raven, J. C. (1938). Progressive Matrices: Sets A, B, C, D, and E. University Press, publiched by HK Lewis.

- 42.Serino S, Repetto C. New trends in episodic memory assessment: immersive 360 ecological videos. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1878. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooke J. System Usability Scale (SUS): A Quick-and-Dirty Method of System Evaluation User Information. Digital Equipment Co Ltd; 1986. p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooke J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996;189(194):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceravolo R, Pagni C, Tognoni G, Bonuccelli U. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of dysexecutive syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2012;3:159. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy G, Jacobs DM, Tang M, Côté LJ, Louis ED, Alfaro B, Mejia H, Stern Y, Marder K. Memory and executive function impairment predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.: Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2002;17(6):1221–1226. doi: 10.1002/mds.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paulwoods S, Tröster AI. Prodromal frontal/executive dysfunction predicts incident dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2003;9(1):17–24. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703910022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaytor N, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. The ecological validity of neuropsychological tests: A review of the literature on everyday cognitive skills. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2003;13(4):181–197. doi: 10.1023/B:NERV.0000009483.91468.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riva G. Virtual reality: An experiential tool for clinical psychology. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2009;37(3):337–345. doi: 10.1080/03069880902957056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renison B, Ponsford J, Testa R, Richardson B, Brownfield K. The ecological and construct validity of a newly developed measure of executive function: The virtual library task. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2012;18(3):440–450. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Júlio F, Ribeiro MJ, Patrício M, Malhão A, Pedrosa F, Gonçalves H, Januário C. A novel ecological approach reveals early executive function impairments in Huntington’s disease. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:585. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahdah MN, Bennett M, Prajapati P, Parsons TD, Sullivan E, Driver S. Application of virtual environments in a multi-disciplinary day neurorehabilitation program to improve executive functioning using the Stroop task. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;41(4):721–734. doi: 10.3233/NRE-172183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dirnberger G, Jahanshahi M. Executive dysfunction in P arkinson’s disease: A review. J. Neuropsychol. 2013;7(2):193–224. doi: 10.1111/jnp.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The tool and datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7006781.