Abstract

Objective

Digital divide in health-related technology use is a prominent issue for older adults. Improving eHealth literacy may be an important solution to this problem. This study aimed to explore the associations between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy among older Chinese adults.

Methods

A total of 2,144 older adults (mean age, 72.01 ± 6.96 years) from Jinan City, China participated in this study. The eHealth Literacy Scale was used to measure eHealth literacy in older adults. A linear regression model was used to analyze the associations among health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy in older Chinese adults.

Results

The mean eHealth literacy score of the older adults was 17.56 ± 9.61. After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and experience of Internet usage, the results of the linear regression showed that health literacy (B = 0.258, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.215–0.302, P< 0.001) and digital skills (B = 0.654, 95% CI = 0.587–0.720, P < 0.001) were positively associated with eHealth literacy. Sensitivity analyses revealed that this association remained robust.

Conclusions

The level of eHealth literacy in older Chinese adults is low. Health literacy and digital skills are associated with eHealth literacy in older adults. In the future, eHealth literacy intervention research should be considered from the perspective of health literacy and digital skills.

Keywords: eHealth literacy, health literacy, digital skill, older adults, China

Background

With the rapid development of electronic health and information technology, a large amount of health information can be transmitted through the Internet, and an increasing number of older adults have begun using the Internet to obtain information and services. 1 According to the China Internet Development Statistics Report, as of June 2022, the Internet use rate of older adults aged 60 and above reached 44.5%. 2 Previous studies have found that the Internet can provide older adults with a variety of online health resources to manage their general and mental health issues and improve their self-care abilities. 3 However, owing to the unevenness of online health resources, older adults must have high eHealth literacy to be able to use these resources scientifically. Previous studies have revealed that older adults with higher eHealth literacy can better utilize digital technology to improve their wellbeing and health, promote self-management of chronic diseases, and improve their quality of life.4,5

In 2006, Norman et al. 6 defined eHealth literacy as the ability of individuals to find, understand, and evaluate online health information through electronic media and apply health information to make relevant decisions and solve health problems. Norman et al. also developed an eHealth literacy assessment tool, the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALs), 7 which is widely used worldwide. 8 A systematic review found that eHealth literacy in older adults was associated with health-related outcomes, 9 such as quality of life, 10 health behavior, 11 and cognitive function. 12 However, it should be noted that older adults face the most difficulty in accessing digital healthcare services and technological opportunities, and unlike young adults, many older adults lack experience with the use of digital health technologies. 13 This means that the level of eHealth literacy in older adults is low, and this has been confirmed in previous studies.14,15 Therefore, in the current era of ageing and informatization, it is urgent to clarify the factors related to eHealth literacy in older adults and formulate relevant intervention plans to effectively solve the outstanding difficulties encountered by older adults in the use of digital health knowledge and service technologies.

The findings of literature reviews have shown that, when analyzing the factors related to eHealth literacy, many studies have paid more attention to sociodemographic characteristics (age, 3 sex, marital status, 16 educational level 17 income, 18 etc.), and experience of Internet usage, 19 and less attention to factors such as health literacy and digital skills. The findings of a previous study have suggested that whether or not an individual has eHealth literacy depends on their ability to use digital devices and previous health knowledge reserves. 20 However, the associations between these two crucial factors and eHealth literacy have rarely been explored in other previous studies. Meanwhile, when eHealth literacy was proposed, Norman et al. constructed a conceptual model, the Lily model, to clarify the connotation of eHealth literacy. The Lily model held that eHealth literacy was the result of a combination of traditional literacy (basic listening, speaking, reading, writing, computing, and understanding skills), information literacy (the ability to find, evaluate, and effectively utilize required information), media literacy (the ability to choose and understand various information media, question and evaluate, and create and produce responses), computer literacy (the ability to use computer hardware and software to solve problems), health literacy (the ability to access, evaluate, understand, and utilize health information and services), and scientific literacy (mastering basic knowledge and scientific methods, and scientific cognitive ability to health). 6 However, it was not validated using a population-based observational study and was only discussed conceptually. At present, the relationship between these six kinds of literacy and eHealth literacy has not been fully clarified. Previous studies on adults, 21 college students, 22 and patients with spinal cord injuries 23 have found that health literacy is related to eHealth literacy. It can be inferred that individuals mainly rely on their original health literacy when understanding and evaluating the health information that they obtain on the Internet. However, it is unclear whether this finding can be generalized to the older population. In addition, the relationship between digital skills and eHealth literacy in older adults remains unclear. Digital skills are derived from computer literacy, which refers to the skills to understand and use various digital devices and resources. 24 With the accelerated digitalization of society, digital skills have become an important and indispensable skill for people's daily life and work. 25 However, there is a lack of research focusing on the associations between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy, especially among older adults.

In view of the shortcomings of previous studies, it is necessary to conduct a study on the relationship between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy in older adults. Therefore, this study aimed to explore this association to provide a scientific basis for improving eHealth literacy in older adults in the future.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study of older adults in Jinan, Shandong Province, China, from March to May 2021. A multistage, stratified cluster random sampling method was used to select participants. In the first stage, each district and county in Jinan city were divided into three layers, high, middle, and low, according to the annual per capita gross domestic product level. Two districts or counties were randomly selected from each layer. In the second stage, two towns or streets were randomly selected from the six randomly selected districts or counties, totaling 12 streets or towns. In the third stage, all older adults in two communities or administrative villages were randomly selected from the 12 randomly selected streets or towns, totaling 24 communities or administrative villages.

The participants' inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥60 years, residence in Jinan for more than 6 months, experience of Internet usage, provision of informed consent, and voluntary cooperation with the investigation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: the presence of hearing and language disorders; serious diseases such as malignant tumors, dementia, schizophrenia; and disability.

Procedures

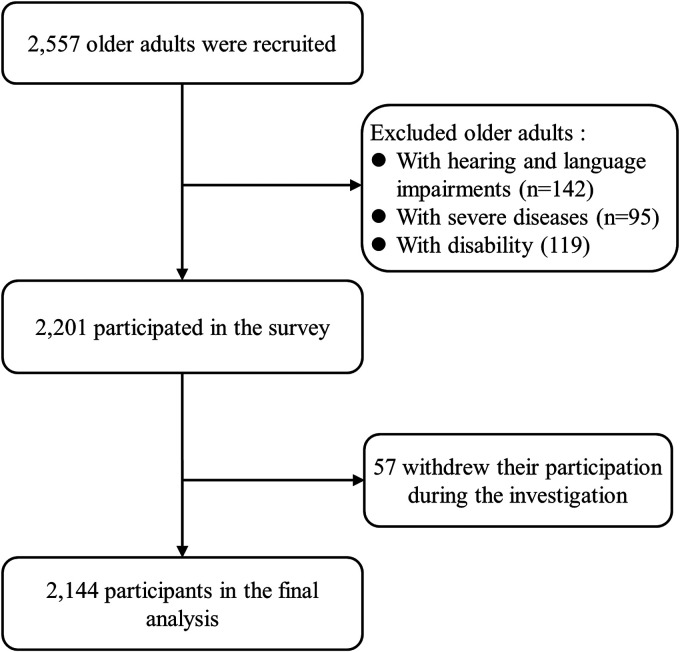

After identifying the selected communities or administrative villages at the sampling stage, we contacted the community or administrative village staff by telephone to introduce them to the content, purpose, and value of the study. After receiving their support, our investigator went to the community or administrative village for an enrolled survey. The investigators consisted of uniformly trained medical undergraduate students. Community or administrative village staff took the investigators into the homes of older adults to conduct paper-based questionnaires with those older adults who met the criteria. All surveys were conducted in an interview style, in which the investigator read the questions, the participants verbally responded, and then the investigator filled in the questionnaire. In this study, 2,557 older adults who met the inclusion criteria were selected as the research participants; 356 met the exclusion criteria and 57 withdrew their participation during the investigation, and were thus excluded. Finally, data from 2,144 older adults were included in the analysis, and the questionnaire response rate was 97.41%. Figure 1 shows the selection process of the participants in this study. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (No: XYGW-2020-101). All the participants provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

The selection process of participants.

Measures

eHealth literacy

The eHEALs was compiled by Norman et al. 7 and translated into Chinese by Yu et al., 26 which was used to assess eHealth literacy by assessing individuals' self-perceived ability to find, understand, and evaluate online health information through electronic media. The scale has a single-factor structure with eight items for assessing the elderly population in the Chinese community. 27 A five-point Likert scoring method was used for each item, and one to five points were scored from “very inconsistent (1)” to “very consistent (5).” The scores range from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating a higher level of eHealth literacy. The scale has good reliability and validity and has been used in older adults. 10 In this study, Cronbach's α coefficient for the scale was 0.983.

Health literacy

The Health Literacy Self-Perception Scale 28 developed by Taiwanese scholars based on the characteristics of older adults was used to assess health literacy by assessing individuals' self-perceived ability to find, understand, and use health information and services. The scale includes 10 items of self-evaluation, and each item is scored using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (5),” and the total score is derived from the sum of all item scores, with higher scores indicating better health literacy. The scale has good reliability and validity in the elderly population. In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.944.

Digital skill

Digital skill was assessed using a self-developed electronic device use and Internet use skills questionnaire (Supplemental material 1), which indirectly reflects individual digital skills through the measurement of skills on how to use the Internet and digital devices. The questionnaire assessed the following: (1) use of electronic devices to type; (2) use of electronic devices to take pictures and videos; (3) use of search engines (Baidu, Sogou, etc.); (4) download of software and various materials; (5) online chatting (WeChat, QQ, etc.); (6) online shopping; (7) online payment (Alipay payment, online banking, etc.); and (8) listening to songs and watching videos online. Each item is scored using a five-point Likert scale (1 = no/very unskilled, 2 = somewhat/unskilled, 3 = fair, 4 = skilled, 5 = very skilled). The total score is derived from the sum of the item scores, with higher scores indicating a higher skill level.

Covariates

The covariates in this study included sociodemographic characteristics and experience of Internet usage. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, sex, residence, marital status, educational level, average personal monthly income, occupation, self-assessed health status, and chronic disease status. Age was divided into three categories: 60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥80 years. Marital status was divided into two categories: married and unmarried (unmarried/divorced/widowed). Health status (1 = poor, 2 = fair, and 3 = good) and chronic disease status (suffering or not suffering from chronic diseases) were self-reported.

Experience of Internet usage includes the duration of Internet usage, the frequency of Internet usage, and the time spent on the Internet each time. We asked the older adults about their experience through the following questions: “How long have you been online since you learned?”; “How often have you been online in the past month?”; and “How long do you spend online each time?”. We categorized their answers to each question as follows: duration of Internet usage: < 1, 1 to 2, 2 to 3, and ≥3 years; frequency of Internet usage: less than once per week, 1 to 2 times per week, 3 to 4 times per week, 5 to 6 times per week, 1 time per day, and multiple times per day; frequency of internet access: occasional (less than once per week and 1–2 times per week), sometimes (3–4 times per week and 5–6 times per week), and often (once a day and many times a day); and time spent on the internet each time: < 1, 1 to 2, 2 to 3, and ≥3 hours.

Data analysis

STATA 17.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for data analysis. All tests were bilateral, and the test level was set at α = 0.05. Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and classification variables were described as frequency (constituent ratio).

The t-test and analysis of variance were used to compare the differences in eHealth literacy, health literacy and digital skills among different sociodemographic characteristics and experience of Internet usage. We conducted two linear regression models to explore the association between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy: model 1 was unadjusted while model 2 was adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and experience of Internet usage. We used the Breusch-Pagan test to test for heteroscedasticity, 29 and the results showed that there was heteroscedasticity. Therefore, we adopted robust standard errors to eliminate bias. 30 In addition, to further verify the heterogeneity of the results, we performed subgroup analysis to determine whether the association differed by sex, age, and residence. Finally, we excluded participants with functional limitations, depressive symptoms, and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) from the sensitivity analysis because participants with these three adverse health events may rarely use the Internet. The measurements of functional limitations, depressive symptoms, and MCI are shown in Supplemental material 2.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive analysis and differences in the scores of health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy among participants with different characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The mean eHealth literacy score of 2,144 older adults was 17.56 (SD: 9.61). In addition, the mean scores of health literacy and digital skill were 32.32 (SD: 8.29) and 14.29 (SD: 7.72), respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants according to health literacy and digital skill.

| Variables | Sample | Health literacy (mean ± SD) | P-value | Digital skill (mean ± SD) | P-value | eHealth literacy (mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 32.32 ± 8.29 | 14.29 ± 7.72 | 17.56 ± 9.61 | ||||

| Age group, years, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 60–69 | 753(35.1) | 33.59 ± 7.64 | 17.26 ± 8.58 | 20.49 ± 9.76 | |||

| 70–79 | 1,069(49.9) | 32.12 ± 8.35 | 13.13 ± 6.87 | 16.56 ± 9.42 | |||

| ≥80 | 322(15.0) | 30.03 ± 9.02 | 11.22 ± 5.77 | 14.03 ± 7.87 | |||

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 1,075(50.1) | 33.90 ± 7.78 | 14.97 ± 7.88 | 18.77 ± 9.70 | |||

| Female | 1,069(49.9) | 30.74 ± 8.50 | 13.61 ± 7.48 | 16.34 ± 9.37 | |||

| Residence, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Urban residents | 829(38.7) | 34.90 ± 7.66 | 17.36 ± 8.68 | 20.56 ± 10.24 | |||

| Rural residents | 1,315(61.3) | 30.70 ± 8.27 | 12.37 ± 6.33 | 15.66 ± 8.67 | |||

| Marital status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Unmarried | 498(23.2) | 29.96 ± 8.41 | 12.27 ± 6.76 | 14.89 ± 8.87 | |||

| Married | 1646(76.8) | 33.04 ± 8.13 | 14.91 ± 7.88 | 18.36 ± 9.68 | |||

| Educational level, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Primary school and below | 1,329(62.0) | 29.97 ± 8.14 | 12.01 ± 5.96 | 15.11 ± 8.47 | |||

| Junior high school | 494(23.0) | 34.94 ± 7.09 | 16.73 ± 8.08 | 20.23 ± 9.97 | |||

| High school and above | 321(15.0) | 38.04 ± 6.48 | 20.00 ± 9.35 | 23.59 ± 9.74 | |||

| Average monthly personal income (CNY), n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <2000 | 1,053(49.1) | 29.53 ± 8.42 | 11.48 ± 5.68 | 14.27 ± 8.05 | |||

| 2000–3000 | 720(33.6) | 33.77 ± 7.08 | 15.56 ± 7.62 | 19.36 ± 9.49 | |||

| >3000 | 371(17.3) | 37.44 ± 6.86 | 19.82 ± 9.16 | 23.40 ± 10.20 | |||

| Occupation, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Farmers | 661(30.8) | 30.61 ± 8.06 | 12.28 ± 6.24 | 15.19 ± 8.46 | |||

| Workers | 760(35.4) | 30.73 ± 8.53 | 12.78 ± 6.81 | 15.88 ± 8.92 | |||

| Public workers | 250(11.7) | 37.80 ± 6.16 | 19.29 ± 8.80 | 23.93 ± 9.62 | |||

| Businessman | 114(5.3) | 36.30 ± 7.70 | 20.13 ± 9.06 | 23.33 ± 9.86 | |||

| No fixed work | 359(16.7) | 33.78 ± 7.35 | 15.89 ± 7.94 | 19.19 ± 9.94 | |||

| Self-reported health, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Poor | 451(21.0) | 28.35 ± 8.6 | 11.56 ± 6.02 | 13.98 ± 7.94 | |||

| Medium | 702(32.7) | 31.55 ± 7.46 | 13.64 ± 6.91 | 16.67 ± 8.95 | |||

| Good | 991(46.2) | 34.68 ± 7.92 | 16.01 ± 8.48 | 19.82 ± 10.14 | |||

| Chronic disease, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1,509(70.4) | 31.78 ± 8.18 | 13.73 ± 7.31 | 16.76 ± 9.24 | |||

| No | 635(29.6) | 33.62 ± 8.44 | 15.63 ± 8.47 | 19.46 ± 10.19 | |||

| Duration of Internet usage (year) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <1 | 1,219(56.9) | 29.54 ± 8.22 | 9.93 ± 4.18 | 12.66 ± 7.00 | |||

| 1–2 | 353(16.5) | 34.33 ± 6.90 | 16.78 ± 5.99 | 21.65 ± 8.40 | |||

| 2–3 | 270(12.6) | 35.60 ± 6.80 | 19.83 ± 7.09 | 23.94 ± 8.30 | |||

| ≥3 | 302(14.1) | 38.30 ± 6.16 | 24.08 ± 7.62 | 26.84 ± 8.65 | |||

| Internet access frequency | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Occasionally | 1,259(58.7) | 29.73 ± 8.21 | 9.87 ± 3.99 | 12.85 ± 7.04 | |||

| Sometimes | 466(21.7) | 34.91 ± 6.87 | 18.48 ± 6.57 | 23.09 ± 8.32 | |||

| Often | 419(19.5) | 37.23 ± 6.74 | 22.92 ± 7.51 | 25.57 ± 9.04 | |||

| Time spent on the internet each time (hours) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <1 | 1,590(74.2) | 30.80 ± 8.29 | 11.58 ± 5.69 | 14.87 ± 8.38 | |||

| 1–2 | 290(13.5) | 36.23 ± 6.43 | 20.75 ± 6.96 | 24.73 ± 8.4 | |||

| 2–3 | 145(6.8) | 36.81 ± 6.69 | 22.79 ± 7.51 | 25.13 ± 8.87 | |||

| >3 | 119(5.6) | 37.61 ± 6.76 | 24.48 ± 7.89 | 26.75 ± 9.09 |

Regression analyses

Table 2 shows the linear regression results for the association between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy. In the unadjusted model, health literacy (B = 0.280, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.238–0.321, P < 0.001) and digital skills (B = 0.767, 95% CI = 0.722–0.813, P < 0.001) were both positively associated with eHealth literacy. After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and experience of Internet usage, health literacy (B = 0.258, 95% CI = 0.215–0.302, P < 0.001) and digital skills (B = 0.654, 95% CI = 0.587–0.720, P < 0.001) remained positively associated with eHealth literacy. Additionally, we conducted subgroup analyses according to sex, age, and residence. The associations of health literacy and digital skills with eHealth literacy were statistically significant in both the unadjusted and adjusted models.

Table 2.

The result of multivariate linear regression analysis.

| Sample | Variable | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Robust SE | β | P | 95% CI of B | B | Robust SE | β | P | 95% CI of B | ||

| Total sample | Health literacy | 0.280 | 0.021 | 0.241 | <0.001 | 0.238–0.321 | 0.258 | 0.022 | 0.223 | <0.001 | 0.215–0.302 |

| Digital skill | 0.767 | 0.023 | 0.616 | <0.001 | 0.722–0.813 | 0.654 | 0.034 | 0.525 | <0.001 | 0.587–0.720 | |

| By sex | |||||||||||

| Male | Health literacy | 0.308 | 0.031 | 0.247 | <0.001 | 0.247–0.369 | 0.302 | 0.032 | 0.243 | <0.001 | 0.239–0.366 |

| Digital skill | 0.756 | 0.033 | 0.614 | <0.001 | 0.692–0.819 | 0.615 | 0.048 | 0.500 | <0.001 | 0.520–0.709 | |

| Female | Health literacy | 0.243 | 0.029 | 0.220 | <0.001 | 0.186–0.300 | 0.217 | 0.030 | 0.197 | <0.001 | 0.159–0.275 |

| Digital skill | 0.782 | 0.033 | 0.624 | <0.001 | 0.718–0.846 | 0.698 | 0.048 | 0.558 | <0.001 | 0.604–0.791 | |

| By age group | |||||||||||

| 60–69 years | Health literacy | 0.374 | 0.039 | 0.293 | <0.001 | 0.297–0.451 | 0.337 | 0.040 | 0.264 | <0.001 | 0.258–0.416 |

| Digital skill | 0.651 | 0.035 | 0.572 | <0.001 | 0.582–0.720 | 0.560 | 0.047 | 0.492 | <0.001 | 0.467–0.652 | |

| 70–79 years | Health literacy | 0.259 | 0.028 | 0.229 | <0.001 | 0.203–0.315 | 0.244 | 0.030 | 0.216 | <0.001 | 0.185–0.302 |

| Digital skill | 0.865 | 0.033 | 0.631 | <0.001 | 0.801–0.928 | 0.808 | 0.044 | 0.590 | <0.001 | 0.722–0.894 | |

| ≥80 years | Health literacy | 0.206 | 0.048 | 0.236 | <0.001 | 0.111–0.301 | 0.207 | 0.053 | 0.237 | <0.001 | 0.102–0.312 |

| Digital skill | 0.645 | 0.110 | 0.472 | <0.001 | 0.428–0.861 | 0.346 | 0.137 | 0.253 | 0.012 | 0.076–0.615 | |

| By residence | |||||||||||

| Urban residents | Health literacy | 0.285 | 0.040 | 0.213 | <0.001 | 0.206–0.363 | 0.265 | 0.043 | 0.198 | <0.001 | 0.181–0.348 |

| Digital skill | 0.742 | 0.034 | 0.629 | <0.001 | 0.675–0.810 | 0.617 | 0.052 | 0.523 | <0.001 | 0.515–0.719 | |

| Rural residents | Health literacy | 0.274 | 0.024 | 0.261 | <0.001 | 0.226–0.322 | 0.250 | 0.026 | 0.239 | <0.001 | 0.200–0.300 |

| Digital skill | 0.803 | 0.034 | 0.586 | <0.001 | 0.737–0.869 | 0.689 | 0.043 | 0.502 | <0.001 | 0.605–0.772 | |

Note: β: standardized regression coefficient; B: unstandardized regression coefficient; CI: confidence interval; SE: standard errors.

Sensitivity analyses

After excluding participants with functional limitations, depressive symptoms, and MCI, the results of sensitivity analyses showed that health literacy and digital skills remained positively associated with eHealth literacy, both in the unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 3). These results suggested that the associations of health literacy and digital skills with eHealth literacy were robust.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses of associations among health literacy, digital skill, and eHealth literacy.

| Sample | Variable | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Robust SE | β | P | 95% CI of B | B | Robust SE | β | P | 95% CI of B | ||

| Excluding function limitations | Health literacy | 0.316 | 0.035 | 0.227 | <0.001 | 0.247–0.385 | 0.315 | 0.036 | 0.227 | <0.001 | 0.244–0.386 |

| Digital skill | 0.737 | 0.030 | 0.611 | <0.001 | 0.678–0.795 | 0.633 | 0.045 | 0.525 | <0.001 | 0.545–0.721 | |

| Excluding depressive symptoms | Health literacy | 0.280 | 0.023 | 0.231 | <0.001 | 0.235–0.325 | 0.263 | 0.024 | 0.217 | <0.001 | 0.217–0.310 |

| Digital skill | 0.769 | 0.024 | 0.624 | <0.001 | 0.723–0.815 | 0.649 | 0.036 | 0.527 | <0.001 | 0.579–0.719 | |

| Excluding MCI | Health literacy | 0.282 | 0.024 | 0.229 | <0.001 | 0.234–0.330 | 0.267 | 0.025 | 0.216 | <0.001 | 0.217–0.316 |

| Digital skill | 0.768 | 0.024 | 0.623 | <0.001 | 0.722–0.814 | 0.665 | 0.032 | 0.540 | <0.001 | 0.603–0.727 | |

Note: β: standardized regression coefficient; B: unstandardized regression coefficient; CI: confidence interval; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; SE: standard errors.

Discussion

We performed a cross-sectional survey of 2,144 older Chinese adults to analyze the associations between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy. The results suggested that health literacy and digital skills were both positively related to eHealth literacy among older Chinese adults. In addition, the subgroup and sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the associations we found.

This study of older Chinese adults reported a mean eHealth literacy score of 17.56, which is lower than those reported in the United States (30.94 ± 6.00), South Korea (30.50 ± 4.62), 31 and Norway (25.66 ± 6.23). 32 This shows that the eHealth literacy of older Chinese adults is low and that intervention is urgently needed for improvement. Currently, eHealth literacy has been widely studied in the general population, patients, and students.33,34 However, research on eHealth literacy among older adults is limited. 9 Although there have been studies exploring factors related to eHealth literacy in older adults, they have only focused on sociodemographic characteristics, Internet usage, and attitude toward Internet health information. 19 As mentioned in the introduction of this article, eHealth literacy ultimately depends on whether individuals have sufficient digital skills and health literacy. The former determines whether they can use the Internet to search for and obtain online health information, while the latter determines whether they can identify and judge information. However, Norman, the proponent of eHealth literacy, only conceptually explained that health literacy and digital skills are among the core skills of eHealth literacy 6 but did not conduct empirical research. Therefore, it is necessary to further verify whether the Lily model of eHealth literacy is established in empirical research.

In this study, a higher health literacy level was associated with eHealth literacy in older adults, which was the first finding in the older population. Conceptually, both health literacy and eHealth literacy contain three core skills of collecting, evaluating, and applying health information, which are conceptually related to each other. A previous study among 1873 college students in China showed a significant positive correlation between health literacy and eHealth literacy. 22 However, a Canadian study did not find a significant correlation between the two, 35 which may be related to the health literacy measurement tools adopted. In the abovementioned study, the Newest Vital Sign 36 was used to evaluate an individual's health literacy. However, this tool mainly measures an individual's understanding and computing ability of the information on nutrition labels, 36 and it is unable to comprehensively measure health literacy. Differences in the content of the assessments may be one of the reasons for the inconsistency with our results. In this study, the possible reason why health literacy was associated with eHealth literacy is that individuals with high health literacy levels have the necessary skills to obtain and understand health information more efficiently online 37 and better distinguish and judge the correctness, scientific nature, and effectiveness of online health information, so as to make better use of eHealth information to promote personal health. In addition, individuals with high health literacy level may be more motivated to take a variety of measures to improve their health status, 38 encouraging them to pay more attention to health information from other sources, thus indirectly relating to eHealth literacy.

The results of this study found that digital skills were also associated with eHealth literacy among older adults, which is similar to the findings of a study of Greek citizens. 39 In addition, previous research on nursing students found that digital literacy affects eHealth literacy, 40 which supports our research findings. The concept of eHealth literacy includes the connotation of online health information collection ability, which must be highly related to digital skills. Older adults with a high level of digital skills are more proficient in using electronic devices correctly and efficiently using search engines to find and obtain online health information, to improve eHealth literacy. In addition, older adults with high digital skills are more likely to obtain online health information and services 41 and have more opportunities to use a variety of online resources to improve their health status, which may stimulate the subjective initiative of individuals, thus promoting their active access to and use of online health resources. In addition, previous studies have found a significant negative correlation between the pressure to use a computer and eHealth literacy among older adults. 42 Older adults with a high level of digital skills may have a stronger self-efficacy in using electronic devices, which may reduce their computer use pressure and improve their ability to obtain and use online health information and services, thus showing a high level of eHealth literacy. However, it should be noted that the results of a study of middle-aged adults in South Korea found that digital skills were not significantly associated with eHealth literacy, 43 contrary to our findings. This difference may be related to the different research populations and measurement tools for digital skills, which suggests that it is necessary to further explore the relationship between digital skills and eHealth literacy in a wider population.

This study has some limitations. First, we used a cross-sectional research design, and the research results could not infer a causal relationship between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy. In the future, a randomized controlled study should be conducted to analyze the impact of health education and digital education on eHealth literacy in older adults to clarify the causal relationship between the three. Second, owing to geographical constraints, whether the results of this study can be extended to other countries and regions remains to be verified. Finally, the measurement of health literacy and digital skills was self-reported, which may have introduced reporting bias. In the future, more objective measurements, such as health knowledge and practical operations, can be used to evaluate the health literacy and digital skills of older adults, which may help reduce the overestimation or underestimation caused by self-reporting.

Despite these limitations, this study has several advantages. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the relationship between health literacy, digital skill, and eHealth literacy among older adults. Our research results present a new idea for improving eHealth literacy in older adults in the future, which is that health literacy and digital skills should be improved first. Second, we controlled for a large number of covariates in the regression model, making our results more robust. Moreover, we conducted a heterogeneity analysis, and the results showed that the associations between health literacy, digital skills, and eHealth literacy were consistent across groups, which implies that future interventions could be generalized rather than requiring targeted interventions for specific groups. In addition, we conducted three sensitivity analyses to further demonstrate the robustness of our associations. Finally, our study corroborates the content of the Lily model of eHealth literacy.

Conclusions

The level of eHealth literacy in older Chinese adults is low. Health literacy and digital skills are associated with eHealth literacy in older adults. In the future, eHealth literacy intervention research should be considered from the perspective of health literacy and digital skills.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231178431 for Associations between health literacy, digital skill, and eHealth literacy among older Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study by Shaojie Li, Guanghui Cui, Yongtian Yin and Huilan Xu in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of this study for their time and dedication.

Footnotes

Contributorship: SL designed the study, completed the data analysis, and manuscript writing. YY and GC collected the data. HX revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (No: XYGW-2020-101).

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Huilan Xu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4845-2252

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Yoon H, Jang Y, Kim S, et al. Trends in internet use among older adults in the United States, 2011–2016. J Appl Gerontol 2021; 40: 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center CINI. The 50th statistical report on China's internet development, http://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2022/0914/c88-10226.html (2022, accessed 9-15 2022).

- 3.Choi NG, DiNitto DM. The digital divide among low-income homebound older adults: internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/internet use. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15: e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bevilacqua R, Strano S, Di Rosa M, et al. eHealth literacy: from theory to clinical application for digital health improvement. Results from the ACCESS training experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 11800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevilacqua R, Casaccia S, Cortellessa G, et al. Coaching through technology: a systematic review into efficacy and effectiveness for the ageing population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norman CD, Skinner HA. Ehealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet Res 2006; 8: e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHEALS: the ehealth literacy scale. J Med Internet Res 2006; 8: e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Lee EH, Chae D. Ehealth literacy instruments: systematic review of measurement properties. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e30644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie L, Zhang S, Xin M, et al. Electronic health literacy and health-related outcomes among older adults: a systematic review. Prev Med 2022; 157: 106997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li S, Cui G, Yin Y, et al. Health-promoting behaviors mediate the relationship between eHealth literacy and health-related quality of life among Chinese older adults: a cross-sectional study. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Aspects Treat Care Rehabil 2021; 30: 2235–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui G, Li S, Yongtian Y. The relationship among social capital, eHealth literacy and health behaviours in Chinese elderly people: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020; 21: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S-J, Yin Y-T, Cui G-H, et al. The associations among health-promoting lifestyle, eHealth literacy, and cognitive health in older Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall AK, Bernhardt JM, Dodd V, et al. The digital health divide: evaluating online health information access and use among older adults. Health Educ Behav 2015; 42: 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoogland AI, Mansfield J, Lafranchise EA, et al. Ehealth literacy in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2020; 11: 1020–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paige SR, Miller MD, Krieger JL, et al. Electronic health literacy across the lifespan: measurement invariance study. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhen L, Han Z, Yan Z, et al. Current situation and influencing factors of e-health literacy among rural older adults in Zhengzhou. Mod Prev Med 2020; 47: 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tennant B, Stellefson M, Dodd V, et al. Ehealth literacy and web 2.0 health information seeking behaviors among baby boomers and older adults. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiferaw KB, Tilahun BC, Endehabtu BF, et al. E-health literacy and associated factors among chronic patients in a low-income country: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020; 20: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Zhao H, Fu J, et al. Current status and influencing factors of digital health literacy among community-dwelling older adults in Southwest China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022; 22: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn S, Bond R, Nugent C. Quantifying health literacy and eHealth literacy using existing instruments and browser-based software for tracking online health information seeking behavior. Comput Human Behav 2017; 69: 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Giudice P, Bravo G, Poletto M, et al. Correlation between eHealth literacy and health literacy using the eHealth literacy scale and real-life experiences in the health sector as a proxy measure of functional health literacy: cross-sectional web-based survey. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S, Cui G, Kaminga AC, et al. Associations between health literacy, eHealth literacy, and COVID-19-related health behaviors among Chinese college students: cross-sectional online study. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e25600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh G, Sawatzky B, Nimmon L, et al. Perceived eHealth literacy and health literacy among people with spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study. J Spinal Cord Med 2022; 46: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Laar E, van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM, et al. The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: a systematic literature review. Comput Human Behav 2017; 72: 577–588. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen N, Li Z, Tang B. Can digital skill protect against job displacement risk caused by artificial intelligence? Empirical evidence from 701 detailed occupations. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0277280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo S, Yu X, Sun Y, et al. Adaptation and evaluation of Chinese version of eHEALS and its usage among senior high school students. Chin J Health Educ 2013; 29: 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou H, Wang J, Li Y. Reliability and validity analysis of the Chinese version of e-Health Literacy Scale in elder population of community. Med Higher Vocational Educ Mod Nursing 2019; 2: 448–451. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung M-H, Chen L-K, Peng L-N, et al. Development and validation of the health literacy assessment tool for older people in Taiwan: potential impacts of cultural differences. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015; 61: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breusch TS, Pagan AR. A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econom J Econom Soc 1979; 47: 1287–1294. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stock JH, Watson MW. Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors for fixed effects panel data regression. Econometrica 2008; 76: 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang E, Chang SJ, Ryu H, et al. Comparing factors associated with eHealth literacy between young and older adults. J Gerontol Nurs 2020; 46: 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brørs G, Wentzel-Larsen T, Dalen H, et al. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the electronic Health Literacy Scale (eHEALS) among patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: cross-sectional validation study. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e17312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faux-Nightingale A, Philp F, Chadwick D, et al. Available tools to evaluate digital health literacy and engagement with eHealth resources: a scoping review. Heliyon 2022; 8: e10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman JL, Caldwell PHY, Scott KM. How adolescents trust health information on social media: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr 2023; 23: 703–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monkmana H, Kushniruka AW, Barnetta J, et al. Are health literacy and eHealth literacy the same or different? Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 245: 178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3: 514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackert M, Mabry-Flynn A, Champlin S, et al. Health literacy and health information technology adoption: the potential for a new digital divide. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xesfingi S, Vozikis A. Ehealth literacy: in the quest of the contributing factors. Interact J Med Res 2016; 5: e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeon J, Kim S. The mediating effects of digital literacy and self-efficacy on the relationship between learning attitudes and Ehealth literacy in nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today 2022; 113: 105378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vehawn J, Richards R, West JH, et al. Identifying barriers preventing Latina women from accessing WIC online health information. J Immigr Minor Health 2014; 16: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arcury TA, Sandberg JC, Melius KP, et al. Older adult internet use and eHealth literacy. J Appl Gerontol 2020; 39: 141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee J, Tak SH. Factors associated with eHealth literacy focusing on digital literacy components: a cross-sectional study of middle-aged adults in South Korea. Digital Health 2022; 8: 20552076221102765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231178431 for Associations between health literacy, digital skill, and eHealth literacy among older Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study by Shaojie Li, Guanghui Cui, Yongtian Yin and Huilan Xu in DIGITAL HEALTH