Abstract

With the prevalence of live streaming e-commerce in the pandemic, brands and platforms cooperate with streamers to join this emerging e-commerce pattern. In the live streaming e-commerce supply chain composed of brand, third-party self-operated platform and streamers with different power, weak and dominant streamer, this paper investigates how the dominant streamer affects the supply chain decision-making under four scenarios composed of different selling formats and different power. Using a game-theoretic model, we find that the market demand can be enlarged by dominant streamer, and the dominant streamer tends to set lower price and lower marketing effort. Furthermore, the member who has the pricing power can obtain higher profit than the scenario in which they lose the power. And with the deeper of the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus among consumers, the streamers will invest more marketing effort as a compensation. Some managerial implications are showed in this paper.

Keywords: Live streaming e-commerce, Supply chain, Dominant streamer, Game theory, Selling format

Introduction

Live streaming e-commerce has become popular in recent years as a new retailing pattern of social e-commerce in China [30]. It is characterized by interactivity, visualization, entertainment, and professionalization [24]. The advantage of real-time interaction with viewers and product display comparing with traditional e-commerce make it a prevalence [12]. The lower price comparing with online shops is a major driving factor for customers to purchase from live streaming channel.1 According to statistics from Iimedia Research,2 market size of live streaming e-commerce has increased from 15.9 billion in 2016 when Taobao launched live streaming e-commerce firstly to 1200 billion in 2020. It has grown about 75 times to reach a trillion market. Especially after the outbreak of COVID-19, the number of users and duration of use meet an explosive growth trend. Data showed that the number of online live streaming users in China reached 638 million in June 2021, among which live streaming e-commerce users accounted for 38%. By the end of 2020, the number of streamers who engaged in the live streaming e-commerce reached 1.234 million.3 Due to the flourishing performance of live streaming e-commerce, many brands and platforms have great passion to try this emerging pattern during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We view live streaming e-commerce channel as a new online channel for some characteristics. Certain stakeholders exist in this new retailing format and live streaming selling has its own operation mechanism and independent profit distribution. The streamers, as known as influencers (i.e., internet celebrities), who introduce product and interact with consumers in the live room are the main role in live streaming e-commerce supply chain. The online shop holders (brand or platform) pay streamers a certain revenue sharing to pay for their marketing efforts. Brands produce and sell product directly to consumers, or wholesale product to third-party self-operated platform, then the platform sells to consumers. In the practice of live streaming e-commerce, live room often make the slogan and promise of the lowest price to attract consumers. As time goes by, the live streaming channel low price consensus among consumers springs up, that is to say, the price of live streaming channel should be lower than other traditional online channels. Therefore, consumers have low price expectation for live streaming channel. When the actual price does not meet consumers' psychological expectation, how will it affect the supply chain decision-making?

Streamers with different power levels will affect the operation effect, and it is not always profitable for the members of live streaming e-commerce supply chain. Streamers are salesman or internet marketer who sell in the live streaming room, they can be distinguished to top, middle, and tail level by the market. The top streamers commonly hold more than ten million followers in the social media and sell out billions GMV (Gross Merchandise Volume) in one live streaming e-commerce activity, such as Jiaqi Li. Normally, the shop holders who located in the upstream of supply chain makes price decision, however, the shop holders and top streamer have unequal status in the live streaming collaboration. Top Streamers, which are scarce in number, have more discourse power than shop holders, and it is usually the shop holder actively seek cooperation with top streamer. The top streamers who motivated by attracting more viewers or consumers to purchase often bargain with shop holders for the lowest price in practice.4 This behavior could do harm to shop holders for they lose the pricing power to some extent in the collaboration with dominant streamer. In this study, top streamer who has huge fan base and network influence, is regarded as a dominant member in the supply chain of live streaming e-commerce. Therefore, shop holders may face a question that which kind of streamer should cooperate with, a weak one or a dominant one? And how this power influence supply chain decision?

No matter agency or wholesale selling format, the brands attempt live streaming e-commerce. For instance, Uniqlo is a Japanese clothing retailer who sells around the world. It operates an online flagship store at Tmall.com in 2006 with the form of agency selling and the store already has 24.62 million followers (who subscribes it) up to now. Apart from agency selling, some brands cooperate with platform by wholesale. For example, JD.com as an authorized reseller of Apple Inc., it holds a self-operated Apple products flagship store. They all sell through streamer's live streaming room. Though many scholars have study selling format selection problems on e-platforms [28, 31], we combine the selling format selection with streamer's power difference in live streaming e-commerce to explore the decisions under different selling formats, and how streamer's power influence the selling format selection strategy of streamer.

The vigorous development of live streaming e-commerce benefits from the support of supply chain, but the research from the perspective of supply chain decision in this field is still insufficient [19, 22]. Based on above background, the following research questions are raised: (1) Should the shop holders cooperate with dominant streamer? Which kind of streamer, weak or dominant, would be more popular among consumer, brand, and platform? (2) Which kind of selling format would streamer prefer considering live streaming channel low price consensus? (3) Does dominant streamer really can expand market demand? How these two factors, dominant streamer and live streaming channel low price consensus, influence supply chain decisions on price, marketing effort, demand and profits of members?

To explore the above research issues, we build game-theoretical model consisting of brand, platform and streamer. According to two kinds of selling format (agency and wholesale) and two types of streamer (dominant and weak), we investigate optimal price, streamer's marketing effort, market demand and profit of each supply chain member under four different scenarios. In agency selling format, the brand is the shop holder who sells product to consumers directly and pay a commission fee to streamer. In wholesale selling format, the brand wholesales product to platform who operates the online shop. We first derive the equilibrium solutions under four scenarios by backward induction and discuss the impact of live streaming channel low price consensus on optimal decisions. Then we compare the optimal solutions to obtain some managerial insights.

Our study obtains several interesting findings. First, the market demand acquires an expansion when dominant streamers get involved in the live streaming e-commerce supply chain. Second, no matter under which selling format, the member (brand, platform, streamer) who has the pricing power can obtain higher profit than the scenario in which they lose the power. Based on above two points, when cooperating with dominant streamer, the shop holders lose pricing power but gain brand awareness; While with weak streamer, the shop holders own pricing power but gain little brand awareness. In other words, the shop holders can select the type of streamers according to their purpose of introduce live streaming channel, for more profit or awareness. Third, the product price set by dominant streamer always lower than that by weak streamer, however, the dominant streamer would like to set lower marketing effort than weak streamer. Hence, lower price and higher marketing effort cannot coexist in the same kind of streamer. Consumer who aims to buy with lower price is suggested to watch top streamer's live streaming room, while those who want to get better marketing services prefer to watch the live streaming room of ordinary streamers. Forth, the marketing effort decreases with the live streaming channel low price consensus. That is to say, the streamer will bear more marketing effort cost to cope with the low price consensus of consumers. Therefore, the streamer should innovate the live streaming marketing method, and the way to attract consumers with low price is not sustainable. Finally, no matter weak or dominant streamers, the streamers prefer agency to reselling format. This explains that in practice, the number of brand stores participating in live streaming e-commerce activities is far more than that of platform self-operated stores.

Our study has following three aspects of contributions. First, introducing the perspective of live streaming channel low price consensus of consumer and streamer's dominant behavior, we fill this gap in decision-making literature of live streaming e-commerce supply chain. Second, our study reveals the influence of dominant streamer on the decision making and provides suggestions for the shop holders to choose the type of streamer. And we explore which selling format is more profitable for the streamer to cooperation with. Third, we study how the live streaming channel low price consensus influence optimal profits and guide the supply chain members to improve revenue by adjusting marketing behavior and manipulating the live streaming channel low price consensus of consumers. Our study provides important implications on cooperating with dominant streamer for members of the live streaming e-commerce supply chain.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review the related literature. In Sect. 3, we establish the model and figure out the equilibrium solutions in each scenario. We analyze and compare the optimal decision variables and profits under four scenarios to give relevant propositions in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, we make a numerical simulation to present the sensitivity and trend visually. Section 6 presents our conclusions and management implications to the members in live streaming supply chain. A discussion of future research directions is also provided. All proofs are shown in “Appendix”.

Literature review

There are three streams of literature are relevant to our study. The first stream is related to live streaming e-commerce, the second stream is dominant supply chain member, and the last stream is about selling format selection.

Live streaming e-commerce

As we study an emerging online retailing format, the most relevant area of literature is live streaming e-commerce. More and more research findings on live streaming e-commerce were published. Besides, the studies on purchase intention (PI) and customer engagement (CE) were comparatively popular filed [6, 23, 24, 30, 37, 38]. Scholars conducted empirical research through questionnaires and semi-structured interview on consumers who had purchase experience in live broadcasting room [7, 20, 41]. Consumer purchase intention is associated with uncertainties in product quality and consumption habit of viewing livestreaming on the basis of dual-process theory [6]. Perceived expertise, perceived similarity, perceived likeability, and perceived familiarity are four important interpersonal interaction factors promoting purchase intention from the perspective of swift guanxi [7]. Cao et al. [4] examined from both internal and external factors to investigate the relation between customer engagement behavior and live streaming e-commerce environment. Trust factor played a significant role in the mechanism of inducing purchase intention and customer engagement. Li et al. [20] found both cewebrity trust and platform trust affect consumers' intention to reuse a certain platform and cewebrity trust plays a more significant role than platform trust. Furthermore, Chen et al. [5] found that PI is influenced by trust and consumers' trust in the streamer can be transferred to product draw on trust transfer theory. Lu and Chen [23] held the view that broadcasters' physical characteristics and values can reduce product uncertainty and then cultivate trust. A few scholars considered the effect of live streaming e-commerce on impulsive consumption from the aspect of the social presence theory and cognitive-affective framework [41], and the complex interaction effects between IT -based atmospheric cues with affordance theory [32].

However, studies pertain to live streaming e-commerce supply chain operation management are still at a nascent stage. Hou et al.5 established a game model to study how the streamers' characteristics consisting of social influence, endorsement reliability and bargaining power influence firm's livestream adoption strategy and paradoxically found that a larger bargaining power of the streamer may be profitable for the firm which is contrary to common sense. Pan et al. [27] also studied the live stream channel introduction strategy considering switch demand, which refers to the consumers who transfer from live stream channel during live stream time to traditional channel. Liu and Liu [22] explored the optimal platform's recommendation effort and streamer's selling effort, then discussed incentive mechanism by a subsidy policy to encourage streamer's selling effort. Jiang and Cai [19] introduced quantities of impulsive consumption into quantitative model. Fan et al. [10] explored the live commerce spillover effect on manufacture's original channel with Stackelberg game and found that the existence of live commerce spillover effect increases manufacture's profit while it cuts down streamer's. Optimal transaction mechanism between retailer and streamer among only commission fee, only fixed fee and both commission and fixed fee was investigated by He et al. [15]. Wang et al. [34] discussed the distribution contract selection between supplier and platform in the context of live streaming e-commerce and put forward the suggestion on the selection of streamer. In this paper, we extend the study of supply chain decisions in the environment of live streaming e-commerce by considering the involvement of a dominant streamer, and discuss the influence of different power streamers on decision making, which has not been studied before.

Dominant supply chain member

Another literature related to this paper is powerful supply chain members' participation in decision-making. At present, the powerful member mainly focuses on the dominant retailer in wholesale selling format. There are two types of modeling stream to reflect retailer dominance. The main research stream takes dominant retailer as the leader in the wholesale selling format from the perspective of different power structures, that is, the dominant retailer as the leader of Stackelberg and the manufacture as the follower [3, 18, 21, 26]. Retailer dominance can result in higher supply chain efficiency [2]. A firm often benefits from its superiority of power and a balanced power structure is often beneficial to the whole supply chain as well as consumers [33]. Analogously, Zhang et al. [40] proposed that the dominant member which is the leader of Stackelberg can improve his and the overall performance of the supply chain. The other stream considers dominant retailer have the pricing power of wholesale price, that is, the pricing power of wholesale price is transferred from the traditional manufacturer to powerful retailer. The dominant retailer dictates the wholesale price while the weak retailer accepts the wholesale price set by manufacturer [11]. Hu et al. [17] considered the supplier wholesales product to a dominant retailer and the negotiated wholesale price decision based on Nash bargaining problem. The dominant retailer sets a wholesale price constraint which is the gap between retail price and wholesale price to constrain the wholesale price [16] or influences the supplier's wholesale price by negotiating with supplier. [9]. Differ from the above articles, our focus is on how the dominant streamer affect the pricing and supply chain performance. In addition, since streamer do not get involved in the wholesale process, this paper treats the dominant streamer as the decision-maker of the product price in the live streaming room, that is, the pricing power of the live streaming channel is transferred from the shop holders to the dominant streamer.

Selling format selection

There is a mass of literature about selling format selection on online platform. Scholars have done plenty of studies on selling formats configuration. Plenty of studies research on the key factors that influence decision making [14, 28, 31, 35, 36, 39]. Pu et al. [28] considered how does online cost including operating cost and commission fee work on manufacture's optimal online distribution strategy and show that agency selling would be better when the commission fee is sufficiently low. Wei et al. [36] examined this problem by introducing two manufactures' different power structure. Hagiu and Wright [14] pointed out that the selling format should match product category and the marketplace for long tail products would be better if the reseller has a variable cost advantage over marketplace. Tian et al. [31] proposed that the decision intuition hinges on the balance between pricing rights and the responsibility for order fulfillment and showed that high order-fulfillment cost and high competition intensity would lead to preferring pure reseller mode. Manufactures selected from direct selling and agent selling under the critical influence of channel competition intensity and transaction fee [39]. Wei et al. [35] found the decisions are affected by factors including e-tailer's channel roles, referral fees and market shares. Some other studies research on the characteristic of agency (i.e., marketplace) selling format. Abhishek et al. [1] proposed the key difference between agency and reselling is who can control the pricing right. Ryan et al. [29] investigated the strategic introduction of marketplace channel when the retail has already established an online website as a direct channel. Mantin et al. [25] showed that by committing to having an active marketplace the retailer can improve its bargaining position with the manufacturer. Ha et al. [13] expanded the choices to both agency and resell channels on online retail platforms and find that the wholesale price is lower as a result of the addition of agency channel. Chen et al. [8] investigated the effects of reselling and agency contracts on the platform's incentive to share information under recommendation scenario and non-recommendation scenario. However, our work contributes to this literature by adding livestream channel to the traditional online channel and examines how this emerging channel influences streamer's online selling format selection. Few of the above papers add livestream channel to online retail channels, which is the focus of our paper.

Model setup

Problem description

We consider the online shop holder (a brand in agency selling format or a platform in wholesale selling format) cooperates with a streamer who sells product to customers in live streaming room. Besides, we only discuss the live streaming channel in this paper and exclude the situations which relate to online traditional channels. There are two types of streamers who own different powers, weak streamer, and dominant streamer. When cooperating with a weak streamer, shop holders make the product price decision in live streaming channel and the weak streamer decides the marketing effort which is provided by streamer. Then, shop holders offer the weak streamer a fraction of the profit as payment, which is widely applied in practice. However, when it comes to dominant streamer, the situation has changed. The product price decision-making power is transferred from shop holders to dominant streamer. We use dominant streamer to portray the top influencers who have a large fan base and greater influence on the internet, and they often have a large number of followers in social media. In live streaming e-commerce, it is often the shop holder who actively seeks cooperation with them, and they have a higher bargaining power with the shop holder, for example, dominant streamers may not accept the product price quoted by shop holders and ask for a lowest price among the whole selling channels for attracting more consumers watching the live streaming activity. We view the behavior that dominant streamer participates in price making as the dominant streamer make the pricing, which relies on top streamers’ power. Thus, the dominant streamer would determine the product price and marketing effort .

In agency selling format, the brand sells to customers directly, such as the brands’ official flagship stores in Tmall (Tmall.com), and the shop holder is brand. In wholesale selling format, the brand wholesales the product to a third-party self-operated platform (e.g., JD.com) as the wholesale price , and the third-party platform decides the unit product profit , thus, the platform as the shop holder sells the product to customers as the price . Analogously, the platform will transfer the pricing power to streamer if the platform cooperates with a dominant streamer.

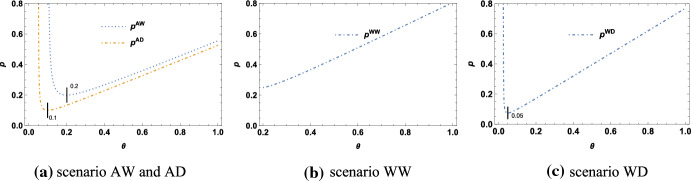

Hence, we get four different live streaming supply chain structures: (I) agency selling format with weak streamer (scenario AW); (II) agency selling format with dominant streamer (scenario AD); (III) wholesale selling format with weak streamer (scenario WW) and (IV) wholesale selling format with dominant streamer (scenario WD). The supply chain diagram is depicted in Fig. 1 as follows.

Fig. 1.

Supply chain structures in four scenarios

Demand function

Here we make some statements and assumptions. First, some products are available in limited quantities and the purchase link was revoked once the products supplied to the live streaming room were sold out in practice. However, we discuss the products which are available for purchasing the whole live time, that is, we assume the supply can meet the demand in this paper. Second, we assume the unit production cost to be zero referring to Abhishek et al. [1] cause the cost variable is not under discussion and this assumption has no impact on the model results.

We assume the willingness to pay for the product in live streaming room is , which is uniformly distributed over [0,1]. As the idea that the price of the live streaming room is lower than that of the traditional online store has been deeply rooted among consumers, thus the willingness to pay for products in the live streaming room has decreased. We use (0 < θ < 1) to denote the popularity of the concept of low price in the live streaming room, in other words, the degree of the live streaming channel low price consensus of consumer. The smaller the is, the greater the degree of the live streaming channel low price consensus of consumer, and the low the willingness to pay. Thus, consumers’ willingness to pay in live streaming channel is ,

Moreover, streamers explain and try out the products during product display in the live streaming room. They show product information to the views, communicate through bullet screen in the real time, and answer consumers' questions about products. The information value and entertainment value provided by streamers’ marketing effort have a positive effect on consumers' purchase intention [7, 12, 23, 37]. We use to denote the marketing effort of the streamer, and the cost of marketing effort satisfies quadratic function which is widely used in previous research [15]. The demand function is derived from consumer behavior and the utility is positive correlation with marketing effort and negative correlation with product price. So the utility function of consumer purchasing in the live streaming room is . The consumer will get utility U from purchasing in the live streaming room, and utility zero from no purchase, therefore, whether a consumer will buy in the live streaming room depends on max {U,0}. The boundary condition of willingness to pay is , and the market demand is . It is obvious that the sensitivity of the market demand on price is , that is, the smaller value is, the greater the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus, consumers are more sensitive to the price of products in the live streaming room, which is consistent with practice. In wholesale selling format, the product price equals to wholesale price plus unit profit (), correspondingly, the market demand is . The notations used in this paper are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations and descriptions

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| θ | The live streaming channel low price consensus of consumer, 0 < θ < 1 |

| k | The cost coefficient of marketing effort, k > 0 |

| r | Commission rate, 0 < r < 1 |

| p | Selling price of the product in live streaming room |

| e | Marketing effort of streamer |

| w | Wholesale price in wholesale selling format |

| m | Unit product profit in wholesale selling format |

| d | Demand of the live streaming channel |

| π | Profit |

We use the subscript b, p and s to denote brand, platform and streamer respectively. And the superscript AW, AD, WW and WD to denote scenario AW, AD, WW and WD respectively.

Scenario AW

In this scenario, the brand sells products through a weak streamer to consumers in agency selling format. The game sequence is as follows. The brand determines price first, then the weak streamer sets marketing effort . Streamers are paid from brands the commission fee per unit of product and bear the cost of marketing effort. Thus, the profits of brand and streamer are and respectively. Solving this optimization problem via backward induction, we can obtain the equilibrium results while for feasible region, in which the optimal results can exist, and the decision variables are positive to exclude the trivial situations. The upper limit of indicates that the commission rate for streamers could not be too high, which is in line with the reality. We summary the equilibrium solutions including price, streamer’s marketing effort, demand, the profits of brands and streamers in Table 2.

Table 2.

Equilibrium solutions under scenario AW and AD

| p* | e* | d* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AW | |||||

| AD |

Scenario AD

In this scenario, the brand sells products through a dominant streamer to consumers in agency selling format. The power of pricing is transferred from brand to dominant streamer due to its influence. Accordingly, the dominant streamer decides the product price and marketing effort for maximizing its profit . The profit of brand in scenario AD is . And the optimization solutions can exist when the commission rate satisfy the condition . Equilibrium solutions including price, streamer’s marketing effort, demand, the profits of brands and streamers are summarized in Table 2.

Scenario WW

In scenario WW, the brand wholesales products to third-party self-operated platform (e.g., JD.com) and the platform cooperates with a weak streamer. In wholesale selling format, the brand is not involved in the subsequent marketing and selling activities. According to the third-party platform has the opportunity to access a large number of consumers, which is an unachievable advantage to brand. We assume that the third-party self-operated platform acts before the brand, that is, the platform has more power than brand. The sequence of this game is as follows. The self-operated platform sets the product price first. Then the brand determines wholesale price and the weak streamer determines marketing effort simultaneously. The profits of the three supply chain members are , , respectively. Here, in order to make the profit of brand a quadratic function about w, to obtain the optimization solutions. We use to denote unit product profit, thus the product price . Backward induction is applied to obtain the equilibrium solutions under the condition . The equilibrium wholesale price, product price, degree of marketing effort, demand, profits of brand, platform and weak streamer are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Equilibrium solutions under scenario WW and WD

| w* | p* | e* | d* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WW | |||||||

| WD |

Scenario WD

In Scenario WD, the brand selects wholesale selling format and the platform cooperates with a dominant streamer. Similar to scenario AD, the dominant streamer has the pricing power. Hence, the dominant streamer decides the product price which is composed of and , and marketing effort simultaneously for maximizing the profit , then the brand sets the wholesale price for maximizing the profit . The profit of third platform is without decision variable. And the optimization solutions can be obtained via backward induction when the commission rate satisfy the condition . The equilibrium wholesale price, product price, degree of marketing effort, demand, profits of brand, platform and weak streamer are summarized in Table 3.

Analysis

In this section, we first analyze the effect of the degree of low price consensus on equilibrium effort, price, demand and profits of pricing members under four scenarios, then compare the equilibrium solutions among different scenarios.

The effect of the degree of low price consensus

Lemma 1

The effect of the degree of low price consensus on equilibrium effort, price, and demand under four scenarios are as follows:

-

(i)

; ; ; .

-

(ii)

; .

-

(iii)

Under scenario AW, if , if , ; Under scenario AD, if , , if , ; Under scenario WW, ; Under scenario WD, if , , if , .

Lemma 1 (i) indicates that the optimal marketing effort decreases with under four scenarios, that is to say, streamers will work harder to promote and display the products in live streaming room with the deeper consensus of low price among consumers, and the streamer also faces a decrease in revenue as a result of marketing effort cost. This may because the marketing effort positively affects market demand, and marketing effort may play a compensatory role when the product price of the live streaming room fails to meet the consumer's expectations.

From Tables 2 and 3, we can see that the optimal demand in the case of weak streamer participation (scenario AW and WW) is fixed value and is not related to consumers' low price consensus and streamer's commission rate. Lemma 1 (i) tells us that the optimal marketing effort increases with the consensus of low price among consumers, but this increased marketing effort has not done much to motivate consumer buying behavior. Interestingly, the equilibrium market demand is the case of dominant streamer is quite different, which is related to consumers’ low price consensus and streamer's commission rate. In addition, the optimal demand decreases with under scenario AD and WD. With the reduction of , the dominant streamer will invest more marketing effort to response to the stronger degree of low price consensus. Meanwhile, the marketing effort also increases with commission rate , and these two sources of marketing effort promotion stimulate the increase in market demand. However, this effort promotion is not effective in the case of weak streamer. On other words, the positive impact of marketing effort on demand is stronger under dominant streamer scenario.

Lemma 1 (iii) implies that the optimal price first decreases then increases with under scenario AW, AD and WD. When the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus of consumer is relatively high, i.e., the value is relatively low, the optimal price decreases with ; when the low price consensus is relatively low, i.e., the value is relatively high, the optimal price increases with . The reasons may be as follows. Low value corresponds to high , and the marketing effort increases with . Thus, the dominant streamer who bearing marketing effort cost will set a higher price to improve profit under scenario AD and WD. Meanwhile, high commission rate means the brand pays more to weak streamer under scenario AW, so that the brand raises price to increase profit. When value is relatively high, the brand and platform will cut price down as a response to the deeper consensus on low price in live streaming channel. High value corresponds to low , thereby leading to low marketing effort. Hence, the shop holders expand demand by reducing price. However, the optimal price under scenario WW always increases with because the region of reduction is excluded from the feasible region.

Lemma 2

The effect of the degree of low price consensus on equilibrium profits of pricing members under four scenarios are as follows:

Under scenario AW, If , , if , ; Under scenario AD, if , if ; Under scenario WW, ; Under scenario WD, if , if .

Analysis in combination with Lemma 1 (iii), the optimal price and profit of pricing members have the same change trend with consensus . The price is determined by dominant streamer when they are involved. While cooperating with weak streamers, the shop holders pricing. Low value deduces high , and the marketing effort increases with . This implies that the impact of consensus on profit of pricing members relates to the commission rate. When the commission rate is low, the marketing effort is low accordingly, thus the brand intends to reduce the price to stimulate demand under scenario AW. With the rise of commission rate, the marketing effort grows as well, thereby expanding the demand and the brand raises the price to gain more profits. Under scenario WW, as the low price consensus deepens, i.e., the value smaller, the price reduced accordingly, then the profit of platform decreases as well combine with fixed demand. Under scenario AD and WD, the dominant streamer inspires the platform formulating higher commission rate for the profit of platform decreases with under a higher , that is, when the live streaming channel members promotes by lower price than other selling channels, the deeper the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus of consumer (i.e., the smaller the value is), the more profit platform can obtain.

Comparative analysis between weak and dominant streamer

Proposition 1

The relationship among optimal price, effort, demand, and wholesale price under four scenarios are as follows:

-

(i)

, .

-

(ii)

, .

-

(iii)

, .

Proposition 1 (i) indicates that the dominant streamer always sets lower product price no matter under which selling format for the consumers are sensitive to price and lower price can attract more consumers to watch the live streaming. When the dominant streamer has the power to decide the product price, the price is made lower than that under weak streamer, which is consistent with practice. The top streamers bargain with shop holders (brand or platform) and publicize that their live streaming rooms offer the lowest price among channels. However, the weak streamers accept the price set by shop holders (brand or platform).

Proposition 1 (ii) shows that the dominant streamer always sets lower marketing effort than weak streamer, because the cost of marketing effort is undertaken by streamer. The cost of marketing effort may include the scene layout in the live streaming room, product presentation script, streamer's live linguistic style training, the lottery in live streaming room to retain fans. Although the marketing effort is always determined by streamers no matter weak or dominant, the decision sequence and pricing power affect the marketing effort. Because the dominant streamer does not lack of the shop holders who want to cooperate with, and its own fan base is the guarantee of sales. However, weak streamer needs to actively seek business opportunities with shop holders and makes hard marketing efforts to attract brand and platform to make up for the lack of influence. In sum, it is better for consumers to get lower price and higher marketing effort, however, these two equilibrium situations cannot coexist in the same type of streamer.

Proposition 1 (iii) implies that the demand can be enlarged by dominant streamer for the lower price and internet appealing power. The dominant streamers bargain with the online shop holders for the goal that old fans can follow them loyally and new fans can be attracted. Thus, the shop holders should prepare enough inventory to support the demand when they cooperate with dominant streamers. In the practice of live streaming e-commerce, the GMV (Gross Merchandise Volume) reached up to 21.5 billion on the first day of pre-sales for 2022 Singles' Day in Li Jiaqi's live streaming room and the consumers watching the live activity reached 460 million.

Proposition 2

The relationship among the optimal profits of brand, platform, and streamer under four scenarios are as follows:

-

(i)

, .

-

(ii)

, .

Proposition 2 (i) and (ii) indicates that the member who has the pricing power can obtain more profit than the other scenario in which it loses the pricing power, because the price setters determine the price for maximizing their own profits. The profit of brand under scenario AW is always higher than that under scenario AD while the profit of streamer under scenario AD is always higher than that under scenario AW. In wholesale selling format, the third-party self-operated platform sets the product price under scenario WW, so that the profit of platform is always higher than that under scenario WD. Another possible explanation is that the price maker is the leader of the Stackelberg game, where the price maker has the first-mover advantage and the following mover makes decision after observing the behavior of first mover.

When brands operate with weak streamers, the optimal demand is a fixed value and the optimal price is higher than that in scenario AD, so that the profit of brand is higher in scenario AW. In cooperation with weak streamers, brand and platform can earn more for higher product prices offset the impact of lower market demand on profits. Then why do they rush to cooperate with dominant streamers? The reason may be the shop holder values the effect of dominant streamers on expanding brand awareness and market share, which is “non-profit income”. It reflects that in reality, there is survival space for weak streamers, because the shop holder can earn more by cooperating with them. On the other hand, it also explains that the shop holder still cooperates with dominant streamers even if they prefer weak streamers from the profit perspective.

However, when it comes to dominant streamer, the marketing effort of dominant streamers is lower than that of weak streamers according to Lemma 1 (i), which brings about lower marketing effort cost. On the other hand, dominant streamers tend to set lower price than weak streamers, which leads to more market demand. The reduction of marketing effort cost and the expansion of market demand have more positive effects on the profit of dominant streamers than the negative effects of price reduction, so that the profit of dominant streamer in scenario AD and WD is higher than that of weak dominant in scenario AW and WW.

Comparative analysis between agency and wholesale selling format

Proposition 3

The relationship among the optimal profit of streamer under four scenarios are as follows:, Proposition 4 shows that streamers prefer agency selling format to wholesale selling format no matter weak or dominant streamers due to the higher profits. This is because the optimal demand in agency selling format is always higher than that in wholesale selling format and there are three members share the live streaming channel revenue in wholesale selling format, while in agency selling format, the brand only needs to pay a fraction of revenue to streamer. Therefore, the third-party self-operated platform should adjust the income composition of streamers to impel them collaborate with platform. This finding is in line with the reality. Taobao (Taobao.com) is a marketplace, and the brands settled in Taobao cooperate with the streamers in live room to directly contact the consumers. However, JD (JD.com) is a third-party self-operated platform, and the number of live rooms and streamers on Taobao is far more than JD.

Numerical simulation

In this section, we present the findings intuitively through numerical examples. We will examine the impact of parameter on the optimal decisions and profits comparison. Without loss of generality and refer to previous literature [10], we assign the cost coefficient of marketing effort to 1, and the commission fee rate to 0.1 according to the business practice that the streamers generally obtain the commission fee between 5 to 25%. All parameter values set in this study are consistent with the assumptions of the model and within the feasible domain.

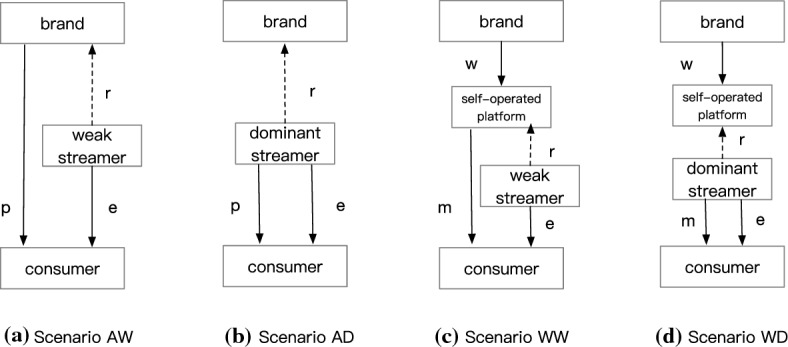

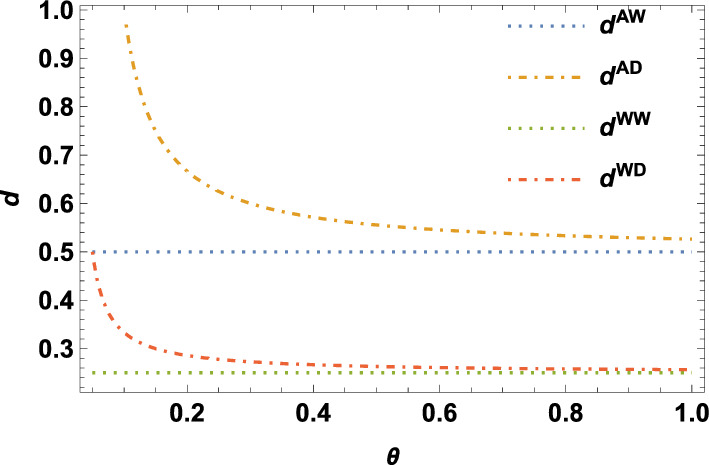

The impact of on optimal decision variables

First, we examine how the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus influence the optimal marketing effort decisions. Figure 2 confirms the results in Lemma 1(i) and Proposition 1(ii). Since the trend is similar under wholesale selling format, here we take the marketing effort under agency as an example. Figure 2 shows that the marketing effort decreases with θ, that is, when the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus increases (the θ value decreases), the marketing effort increases, which is beneficial to consumers. Besides, weak streamers put in more effort than dominant streamers. When dominant streamers have the pricing power in scenario AD and WD, they will set lower marketing effort for undertaking lower marketing effort cost. Combining with the commission rate, the higher the commission rate is, the greater the marketing efforts streamers put in. This illustrates that commission rate can effectively motivate streamers to improve.their efforts in the live streaming room.

Fig. 2.

The impact of and on

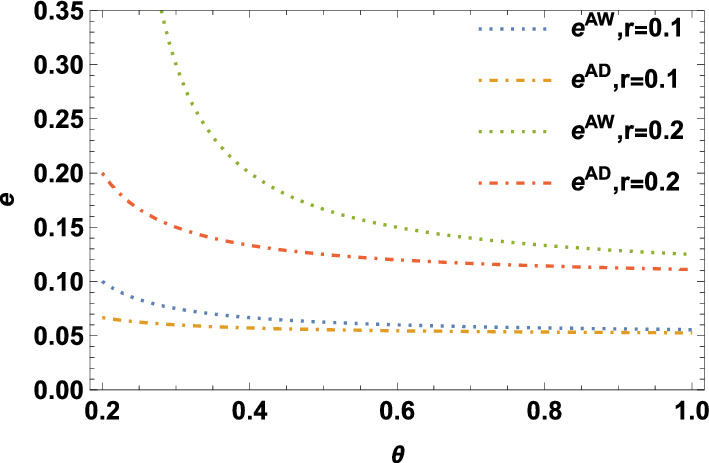

Second, Fig. 3 displays comparison of optimal demand under four scenarios. The demand in wholesale selling format is a fixed value, which confirms the equilibrium solutions in Tables 2 and 3. While the demand in agency selling format decreases with θ, which confirms the results in Lemma 1(ii). With the deeper the concept of low price, the streamers improve marketing effort, thus the demand can be expanded. In addition, it is apparent in Fig. 3 that dominant streamer can expand the demand and the agency selling format is beneficial to expand the demand as well. This confirms Proposition 1(iii) that dominant streamer’s fan base and internet influence play a positive role in enlarging the demand.

Fig. 3.

The impact of on

Third, Fig. 4 shows the results of a numerical experiment to examine how the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus influence the optimal price under four scenarios. As shown in Fig. 4, the optimal price first decreases then increases with under scenario AW, AD and WD, while it always increases with under scenario WW. In this example, the threshold values of under scenario AW, AD and WD are 0.2, 0.1 and 0.05 respectively. When the value exceeds the threshold, as the degree of low price consensus gets deeper, i.e., the value falls, optimal price will be set lower to meet consumers' expectations for the price of live streaming channels. Besides, the price under weak streamer engagement is slightly higher than that under dominant streamer no matter which selling format, which confirms Proposition 1(i).

Fig. 4.

The impact of on

The impact of on optimal profits

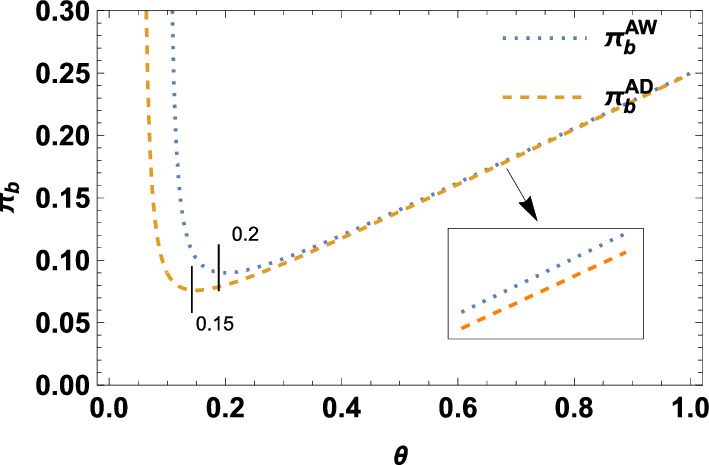

Figure 5 illustrates the profit of brand in agency selling format. We examine how the live channel low price consensus influence brand’s profit and compare the profits between scenario AW and AD. As shown in Fig. 5, when the value is below the threshold, profit decreases with it. Once the value exceeds the threshold, profit increases with it. In this numerical example, the threshold values of under scenario AW and AD are 0.2 and 0.15 respectively. In addition, we can find that the profit of brand in cooperation with weak streamers is higher than that of dominant streamers, which confirms Proposition 2 (i). This is because brand has pricing power under scenario AW and the pricing side is more profitable.

Fig. 5.

The impact of on

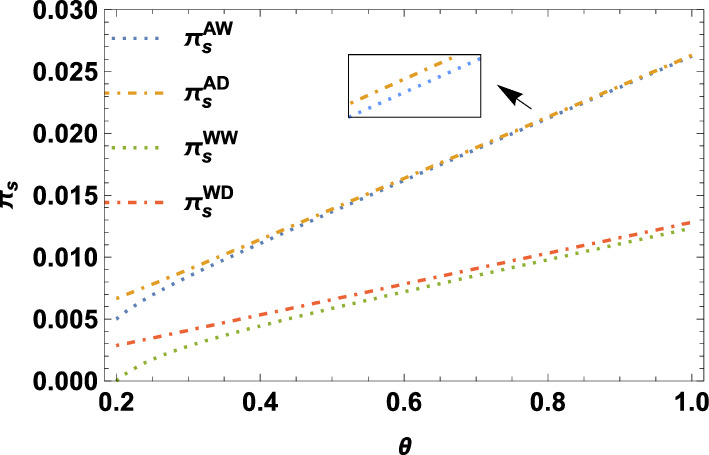

Figure 6 shows the comparison of streamer's profits under four scenarios. As depicted in Fig. 6, the dominant streamer who has the pricing power can obtain more profit than the other scenario under which the weak streamer loses the pricing power, However, the profit gap between dominant and weak streamers is very small under the same selling format. Moreover, it is obvious that the profit of streamer in agency selling format is higher than that in wholesale selling format no matter weak or dominant streamer, which confirms the results in Proposition 3. This phenomenon may because revenue sharing members in wholesale selling format is more than agency selling format.

Fig. 6.

The impact of on

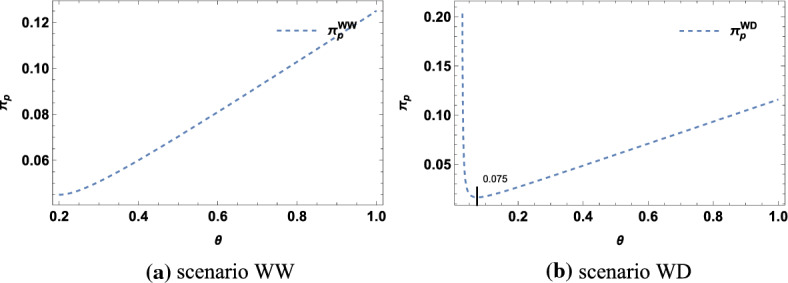

Figure 7 displays the profit of platform in wholesale selling format. Similar to the profit of brand in agency selling format, the profit of profit in cooperation with weak streamers is higher than that of dominant streamers for the platform has pricing power under scenario WW and the pricing side is more profitable, which confirms Proposition 2 (ii). The optimal profit of platform first decreases then increases with under scenario WD. In this numerical example, the threshold values of under scenario WW is 0.075. It has the similar trend with the optimal price under scenario WD for the price is set by platform.

Fig. 7.

The impact of on

Conclusion

Live streaming e-commerce has been developed for almost six years since 2016 in China and gains rapid growth in COVID-19 pandemic period. A batch of streamers are trained to engaged in this emerging industry for the considerable revenue. Some of them accumulate huge number of followers in several social apps such as Douyin and Xiaohongshu in China, then they introduce the products, communicate with consumers in live streaming room as an online seller. The shop holders (brand in agency selling format and third self-operated platform in wholesale selling format) cooperate with streamers who has different influence levels. The dominant streamer who owns millions of fans bargain with shop holders for lower price to attract more consumers. The shop holders who want to take advantage of the huge traffic have to accept the quotation of dominant streamer, thus they are in an inferior position in the live streaming e-commerce supply chain. In this paper, we discuss how the dominant streamer influence the equilibrium solutions under agency and wholesale selling format, then we obtain four scenarios (AW, AD, WW, WD) to examine. By comparing the equilibrium solutions among four scenarios, we draw some conclusions as follows.

First, the demand under dominant streamer engagement is higher than that under weak dominant, that is to say, dominant streamer can expand the market demand in live streaming channel which is exactly what the shop holders who expect to expand awareness want. Second, the members no matter streamer or shop holders gain more profit in the scenario which they have the pricing power than the scenario in which they lose the pricing power. Thus, the members will prefer holding the pricing power to ceding it. Third, the price made by dominant streamers is lower than that made by weak streamers, while the marketing effort made by dominant streamers is lower. Lower price and higher marketing effort are expected results from the perspective of consumers, while the expected results cannot coexist in the same kind of streamer. Fourth, the optimal marketing effort decreases with parameter , that is, when the value decreases, the degree of live streaming channel low price consensus gets deeper, streamers will improve more marketing effort and invest more effort cost. If consumers extraordinary care about the price, streamers will serve the consumers more diligently. Finally, the streamers always prefer agency selling format for higher profit and this preference is irrelated to the power.

Following managerial implications can be obtained from the above analysis. For the shop holders, it is not a wise idea to rely on dominant streamer very much. What is worth to note is that the shop holders can obtain more profit under weak streamers engagement. The dominant streamers ask for pricing power and this behavior may weaken the upstream supply chain members’ power. When the shop holders cooperate with dominant streamers frequently and neglect the weak streamers, this phenomenon may narrow the weak group. Some unknown brands can cooperate with dominant anchors for the purpose of increasing popularity and awareness, however, for some famous brands that consumers are familiar with, it is profitable to cooperate with the weak streamer. For streamers, they should innovate the marketing mode in live streaming channel and reduce the live channel low price consensus of consumers. It is unsustainable to reduce the price in live channel blindly and squeeze profit space. The deeper the low price consensus, the consumers are more sensitive to the live streaming channel price, and the streamers will pay more marketing effort cost. Thus, the streamer can improve the shopping experience of the live broadcast channel with improved after-sale service to maintain consumer loyalty.

There are several limitations to our paper which can be extended in the future. First, brands normally own online mature traditional e-commerce channels, and what is impact of emerging live streaming channel on the original channels? Is it a promotion or a block? We merely discuss the single live streaming channel in this paper. Second, a revenue distribution mechanism should be proposed to stimulate the shop holders (brand or third self-operated platform) move to a common selection in which the streamers and shop holders will not compete the pricing power. Third, the difference between weak and dominant streamers is not just the pricing power, for instance, the number of the followers which reflects influence could be introduced to the demand function to refine the model. The above limitations are not mentioned in this paper and are worthy studying in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX22_1246).

Appendix

Proof of Table 1

Equilibrium solutions under scenario AW

Since the second order partial derivative of is , the profit of streamer under scenario AW is concave in . Thus, by solving , we get . Through backward induction, we substitute into the profit of brand, which is .

Similarly, the second order partial derivative of is , we assume that to ensure the profit of brand under scenario AW is concave in . Thus, by solving , we get , then we substitute into , we can obtain .

By substituting and into , , , we get , , . For ensuring the profit of streamer is positive, we assume that . Thus, the feasible region of scenario AW is .

Equilibrium solutions under scenario AD

Computing the second order partial derivatives of with respect to , , we obtain the following Hessian matrix . Since < 0, and , for ensuring is jointly concave in and , we assume so that By solving and simultaneously, we have and . Then we substitute and into , , to get , and .

Proof of Table 2

Equilibrium solutions under scenario WW

Since the second order partial derivative of with respect to and the second order partial derivative of with respect to are negative, that is, , =. Thus, the profit of streamer and brand under scenario WW are all concave in and respectively. Then, by solving and simultaneously, we obtain and . By substituting and into , for ensuring the second order partial derivative of with respect to , , we assume . Then, by solving , we obtain . Then the other equilibrium solutions can be obtained.

Equilibrium solutions under scenario WD

Since the second order partial derivative of is , the profit of brand under scenario WD is concave in . Thus, by solving , we get . Through backward induction, we substitute into the profit of streamer, which is . Computing the second order partial derivatives of with respect to , , we obtain the following Hessian matrix . Since <0, and for ensuring is jointly concave in and , we assume . By solving and simultaneously, we have and . Then the other equilibrium solutions can be obtained.

Proof of Lemma 1

-

(i)

The first order derivative of with respect to are respectively.

-

(ii)

The first order derivative of with respect to are , respectively.

-

(iii)

The first order derivative of with respect to are respectively. If , if , ; If , , if , ; If , , if , .

Proof of Lemma 2

The first order derivative of with respect to are respectively. If , , if , ; If , if ; If , if .

Proof of Proposition 1

-

(i)

within the common feasible range of scenario AW and AD, which is . within the common feasible range of scenario WW and WD, which is .

-

(ii)

within the common feasible range of scenario AW and AD, which is . within the common feasible range of scenario WW and WD, which is .

-

(iii)

within the common feasible range of scenario AW and AD, which is . within the common feasible range of scenario WW and WD, which is .

-

(iv)

within the common feasible range of scenario WD and WW, which is .

Proof of Proposition 2

-

(i)

and within the common feasible range of scenario AW and AD, which is .

-

(ii)

and within the common feasible range of scenario WW and WD, which is .

-

(iii)

within the common feasible range of scenario WW and WD, which is .

Proof of Proposition 3

within the common feasible range of scenario AW and WW, which is , within the common feasible range of scenario AD and WD, which is.

Data availability

We do not analyze or generate any datasets, because our work proceeds within a theoretical and mathematical approach.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Hou, J., Shen, H., & Xu, F. (2021). A Model of Livestream Selling with Online Streamers. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3896924.

Available at https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/80320.html (Accessed 2022).

Available at https://www.iresearch.com.cn/Detail/report?id=3841&isfree=0 (Accessed 2022).

Available at https://www.163.com/dy/article/GP6TR1E505391QL6.html (Accessed 2022).

Hou, J., Shen, H., & Xu, F. (2021). A Model of Livestream Selling with Online Streamers. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.3896924.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abhishek V, Jerath K, Zhang ZJ. Agency selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic retailing. Management Science. 2016;62(8):2259–2280. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2015.2230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almehdawe E, Mantin B. Vendor managed inventory with a capacitated manufacturer and multiple retailers: Retailer versus manufacturer leadership. International Journal of Production Economics. 2010;128(1):292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bian JS, Lai KK, Hua ZS. Service outsourcing under different supply chain power structures. Annals of Operations Research. 2017;248(1–2):123–142. doi: 10.1007/s10479-016-2228-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao J, Li J, Wang Y, Ai M. The impact of self-efficacy and perceived value on customer engagement under live streaming commerce environment. Security and Communication Networks. 2022;2022:2904447. doi: 10.1155/2022/2904447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C-D, Zhao Q, Wang J-L. How livestreaming increases product sales: Role of trust transfer and elaboration likelihood model. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2022;41(3):558–573. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2020.1827457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, Chen H, Tian X. The dual-process model of product information and habit in influencing consumers’ purchase intention: The role of live streaming features. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 2022;53:101150. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2022.101150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HQ, Zhang SH, Shao BJ, Gao W, Xu YJ. How do interpersonal interaction factors affect buyers' purchase intention in live stream shopping? The mediating effects of swift guanxi. Internet Research. 2022;32(1):335–361. doi: 10.1108/intr-05-2020-0252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Li B, Chen W, Wu S. Influences of information sharing and online recommendations in a supply chain: Reselling versus agency selling. Annals of Operations Research. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10479-021-03968-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du S, Sheng J, Peng J, Zhu Y. Competitive implications of personalized pricing with a dominant retailer. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review. 2022;161:102690. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2022.102690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan TJ, Wang L, Song Y. Impact of live commerce spillover effect on supply chain decisions. Industrial Management & Data Systems. 2022;122(4):1109–1127. doi: 10.1108/imds-08-2021-0482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geylani T, Dukes AJ, Srinivasan K. Strategic manufacturer response to a dominant retailer. Marketing Science. 2007;26(2):164–178. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1060.0239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo L, Hu X, Lu J, Ma L. Effects of customer trust on engagement in live streaming commerce: Mediating role of swift guanxi. Internet Research. 2021;31(5):1718–1744. doi: 10.1108/INTR-02-2020-0078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha AY, Tong S, Wang Y. Channel structures of online retail platforms. M&Som-Manufacturing & Service Operations Management. 2021 doi: 10.1287/msom.2021.1011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagiu A, Wright J. Marketplace or reseller? Management Science. 2015;61(1):184–203. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2014.2042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He Y, Chen L, Mu J, Ullah A. Optimal contract design for live streaming shopping in a manufacturer–retailer–streamer supply chain. Electronic Commerce Research. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10660-022-09591-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B, Meng C, Xu D, Son Y-J. Supply chain coordination under vendor managed inventory-consignment stocking contracts with wholesale price constraint and fairness. International Journal of Production Economics. 2018;202:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu CL, Liu B, Liu YH. Strategic response to a powerful downstream retailer: Difference-setting wholesale pricing contract and partial forward integration. Journal of Systems Science and Systems Engineering. 2022;31(1):89–110. doi: 10.1007/s11518-021-5505-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H, Ke H, Wang L. Equilibrium analysis of pricing competition and cooperation in supply chain with one common manufacturer and duopoly retailers. International Journal of Production Economics. 2016;178:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y, Cai H. The impact of impulsive consumption on supply chain in the live-streaming economy. IEEE Access. 2021;9:48923–48930. doi: 10.1109/access.2021.3068827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li DH, Zhang GZ, Xu Z, Lan Y, Shi YD, Liang ZY, Chen HW. Modelling the roles of cewebrity trust and platform trust in consumers' propensity of live-streaming: An extended TAM method. Cmc-Computers Materials & Continua. 2018;55(1):137–150. doi: 10.3970/cmc.2018.055.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Xu Y, Deng F, Liang X. Impacts of power structure on sustainable supply chain management. Sustainability. 2018;10(1):55. doi: 10.3390/su10010055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu HLS. Optimal decisions and coordination of live streaming selling under revenue-sharing contracts. Managerial and Decision Economics. 2021 doi: 10.1002/mde.3289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu B, Chen Z. Live streaming commerce and consumers’ purchase intention: An uncertainty reduction perspective. Information & Management. 2021;58(7):103509. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2021.103509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma L, Gao S, Zhang X. How to use live streaming to improve consumer purchase intentions: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2022;14(2):1045. doi: 10.3390/su14021045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantin B, Krishnan H, Dhar T. The strategic role of third-party marketplaces in retailing. Production and Operations Management. 2014;23(11):1937–1949. doi: 10.1111/poms.12203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan KW, Lai KK, Leung SCH, Xiao D. Revenue-sharing versus wholesale price mechanisms under different channel power structures. European Journal of Operational Research. 2010;203(2):532–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2009.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan R, Feng J, Zhao Z. Fly with the wings of live-stream selling—Channel strategies with/without switching demand. Production and Operations Management. 2022 doi: 10.1111/poms.13784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pu XJ, Sun SX, Shao J. Direct selling, reselling, or agency selling? Manufacturer's online distribution strategies and their impact. International Journal of Electronic Commerce. 2020;24(2):232–254. doi: 10.1080/10864415.2020.1715530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan JK, Sun D, Zhao XY. Competition and coordination in online marketplaces. Production and Operations Management. 2012;21(6):997–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01332.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Shao X, Li X, Guo Y, Nie K. How live streaming influences purchase intentions in social commerce: An IT affordance perspective. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 2019;37:100886. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2019.100886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian L, Vakharia AJ, Tan Y, Xu Y. Marketplace, reseller, or hybrid: Strategic analysis of an emerging e-commerce model. Production and Operations Management. 2018;27(8):1595–1610. doi: 10.1111/poms.12885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Luo X, Hua Y, Benitez J. Big arena, small potatoes: A mixed-methods investigation of atmospheric cues in live-streaming e-commerce. Decision Support Systems. 2022;158:113801. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2022.113801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang JC, Wang YY, Lai FJ. Impact of power structure on supply chain performance and consumer surplus. International Transactions in Operational Research. 2019;26(5):1752–1785. doi: 10.1111/itor.12466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, Zhao N, Ji X. Reselling or agency selling? The strategic role of live streaming commerce in distribution contract selection. Electronic Commerce Research. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10660-022-09581-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei J, Lu J, Wang Y. How to choose online sales formats for competitive e-tailers. International Transactions in Operational Research. 2021;28(4):2055–2080. doi: 10.1111/itor.12777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei J, Lu JH, Zhao J. Interactions of competing manufacturers' leader-follower relationship and sales format on online platforms. European Journal of Operational Research. 2020;280(2):508–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2019.07.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wongkitrungrueng A, Assarut N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu X, Wu JH, Li Q. What drives consumer shopping behavior in live streaming commerce? Journal of Electronic Commerce Research. 2020;21(3):144–167. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Li Y, Ma Y. Direct selling, agent selling, or dual-format selling: Electronic channel configuration considering channel competition and platform service. Computers & Industrial Engineering. 2021;157:107368. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2021.107368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang TL, Guo XF, Hu J, Wang NN. Cooperative advertising models under different channel power structure. Annals of Operations Research. 2020;291(1–2):1103–1125. doi: 10.1007/s10479-019-03257-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Cheng X, Huang X. “Oh, My God, Buy It!” Investigating impulse buying behavior in live streaming commerce. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. 2022 doi: 10.1080/10447318.2022.2076773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We do not analyze or generate any datasets, because our work proceeds within a theoretical and mathematical approach.