Abstract

CDKL5 deficiency disorder (CDD), a severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, is being diagnosed earlier with improved access to genetic testing, but this may also have unanticipated impacts on parents’ experience receiving the diagnosis. This study explores the lived experience of parents receiving a diagnosis of CDD for their child using mixed methods. Thirty-seven semistructured interviews were conducted with parents of children with a diagnosis of CDD, which were coded and analyzed to identify themes. Grief was a nearly universal theme expressed among participants. Parents of younger children discussed grief in the context of receiving the diagnosis, whereas parents of older children indicated they were at different stages along the grieving journey when they received the diagnosis. Parents with less understanding of their child’s prognosis (poorer prognostic awareness) connected their grief to receiving the diagnosis as this brought a clear understanding of the prognosis. Several themes suggested what providers did well to improve the diagnostic experience for parents, much of which aligns with existing literature around how to provide serious news. Additionally, parents identified long-term benefits of having a diagnosis for their child’s medical problems. Although interview data were concordant with a survey of parents’ diagnostic experience from a large international cohort, most participants in this study were relatively affluent, white mothers and further research is needed to better understand if other groups of parents have a different diagnostic experience. This study gives context of parental experience that providers should be aware of when conveying new genetic diagnoses to families.

Keywords: genetics, children, epileptic encephalopathy, neurodevelopment, quality of life, next-generation sequencing, risk factors

Introduction

CDKL5 deficiency disorder (CDD) is a severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy caused by pathogenic variants in the CDKL5 gene.1–3 Typically, individuals experience lifelong epilepsy, which starts in the first months of life, as well as significant motor and intellectual impairment, with ∼25% of female patients and fewer males achieving independent walking and less achieving any verbal expressive language.4,5 Cortical visual impairment is present in most patients as well as potentially debilitating gastrointestinal comorbidities.6 Historically, patients were not diagnosed or diagnosed later in life, often after a prolonged diagnostic odyssey. However, improvements in technologies and accessibility of genetic testing have resulted in an earlier diagnosis for many genetic conditions, particularly early-onset epileptic encephalopathies. Although there are many important benefits of early diagnosis in the era of personalized medicine,7 the associated psychological impacts on families must also be considered, especially for diagnoses associated with poorer prognosis.

The parental experience of receiving a diagnosis for their child of CDD or other severe genetic epilepsy syndrome has rarely been explored in the literature to date. Literature on delivering serious news tends to focus on cancer diagnoses,8–10 with less consideration of genetic diagnoses that can be similarly life-altering for patients and families. Although some literature exists on parents’ experiences living with or raising a child with a particular genetic syndrome,11–13 few studies have addressed the experience of receiving a genetic diagnosis.14–16 The literature suggests that the diagnostic experience can be negative for families, leaving them confused about the implications and unsure about what to do next.14–16 This experience is likely to be exacerbated by earlier diagnosis with families unprepared for the prognostic implications of a challenging diagnosis. To assist providers in appropriately sharing new genetic diagnoses, as well as supporting families after the diagnosis and implementing appropriate care, we must first understand parent perspectives of their diagnostic experiences.

Using semistructured qualitative interviews, this study explored parents’ lived experiences of receiving their child’s CDD diagnosis. Of interest was the overall experience and how this might vary according to the age of the child at the time of diagnosis. We were interested in several aspects of that experience, including the way that providers informed parents; the emotions the parent experienced as a result of receiving the diagnosis; what the families were told at the time of diagnosis and whether this was helpful; parents’ perspective of what was helpful or detrimental about the diagnostic experience; the longer-term impact that the diagnosis had on parents and their family; and the parents’ perception of the diagnosis at the time of the interview.17

Methods

This study describes parents’ experience receiving a diagnosis of CDD using mixed methods. A phenomenological study was conducted to describe the meaning and experiences of receiving the CDD diagnosis for the parents18 using parent interviews conducted in 2018–2019. Since 2012, data have also been collected from families in the International CDKL5 Database (ICDD) on this topic using both Likert-scale questions and open-ended text fields. The themes identified inductively from the parent interviews were applied deductively to the open-field questions. Likert-based survey questions were analyzed quantitatively.

Semistructured interviews were conducted by a trained qualitative research assistant (RM) under the guidance of expert doctoral level qualitative methodologists (MF and MM). The interview guide probed the topics outlined in the study aims above. The interviewer had no prior relationship with the interviewees or their family members and was not connected to the CDD community prior to the study.

The PI of the study (SD) is a physician involved in the care of many of the CDD patients whose parents were interviewed and is involved in the CDD community. Patients were recruited from the Children’s Hospital Colorado Rett Clinic, which provides care for patients with CDD, as well as from the broader CDD community through announcements distributed by the International Foundation for CDKL5 Research. A total of 76 parents were approached by phone, e-mail, or in person, with 37 parents completing an interview. During recruitment or interviewing, 1 parent explicitly declined to participate, 10 parents never completed the consent process, 7 participants did not respond to scheduling requests or were unable to find an interview time, and 1 parent withdrew.

For maximum variation, we intentionally recruited parents of children who represented a range of ages when diagnosed, with a goal of at least 10 participants whose children were diagnosed under the age of 2 years and 10 participants whose children were diagnosed over the age of 10 years. Additionally, mothers and fathers were actively recruited for participation.

All interviews were conducted over the phone and were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and combined with the interviewer’s field notes for analysis. We discontinued recruitment once we reached thematic saturation. RM and SD conducted the data analysis with regular methodologic guidance by MM. Coded data were entered into ATLAS.ti 8 qualitative data management software for data management. The team inductively developed a codebook that began with immersion in the data and independent opencoding of a subset of transcripts. After iteratively developing an agreed upon codebook, a research assistant (RM) coded the remaining transcripts, with 20% of the transcripts double coded by another team member (SD). All discrepancies were reconciled through consensus. Coded data were analyzed within and across participant groups to identify themes. The first phase of this included identification of the range of responses for a given question followed by the creation of relationship maps displaying how certain responses related to other responses. Reporting of data has been performed according to COREQ guidelines.19

The International CDKL5 Disorder Database (ICDD), which has collected data from caregivers of children with CDD since 2012,20 includes a section in its baseline questionnaire relating to parents’ perspectives on whether the diagnosis was explained properly and on their satisfaction with the information provided to them at that time (Likert response options). Survey respondents also had the opportunity to complete an open question to reflect on their experience of receiving a diagnosis for their child and the impact this has had on themselves and their family. Themes identified in the qualitative interviews were used to deductively code the text that parents contributed to the open fields, into binary responses based on the presence or absence of that theme in each response. Coding was performed by HL and MJ.

To ensure rigor in the methods, the research team had a flattened power hierarchy in which all team members had equal power in decisions about the methods and results. The team regularly practiced reflexivity, naming biases, and discussing each person’s role and effects in the research process. The team kept an audit trail of all decisions throughout the study to ensure dependability and confirmability.

Descriptive statistics were used to present any variation in perceptions according to the child’s birth year, region of residence, and age at and calendar year of diagnosis. These relationships were evaluated for significance using chi-square test only for the quantitative (Likert-scaled response) survey data (see Supplementary Table 1).

Results

As outlined in Table 1, the majority of the 37 participants were white, married women and somewhat more affluent and educated than US national averages, which is where all interview participants were recruited. Participants had a wide range of ages at the time of diagnosis and the age of the child at time of diagnosis was also wide ranging with 21 of the participants having children diagnosed at a young age (under 1 or 2 years of age) and 10 participants with children diagnosed when they were over the age of 10 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Interview Participants.

| Demographics | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Female | |

| Female | 31 |

| Male | 4 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 31 |

| Race | |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other race | 3 |

| White | 31 |

| Marital status | |

| Divorced | 1 |

| Married | 32 |

| Single | 1 |

| Widowed | 1 |

| Age of child at diagnosis, y | |

| < 1 | 16 |

| 1–2 | 5 |

| 2–9 | 6 |

| > 10 | 10 |

| Age of Parent at diagnosis, y | |

| 25–30 | 8 |

| 31–40 | 18 |

| 41–60 | 9 |

| Household income | |

| ≥$150,000 | 7 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 7 |

| $60,000–$99,999 | 16 |

| ≤$59,999 | 5 |

| Highest level of education | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 |

| Postsecondary degree | 10 |

| High school diploma or equivalent degree | 6 |

| No degree | 4 |

Conceptual Model

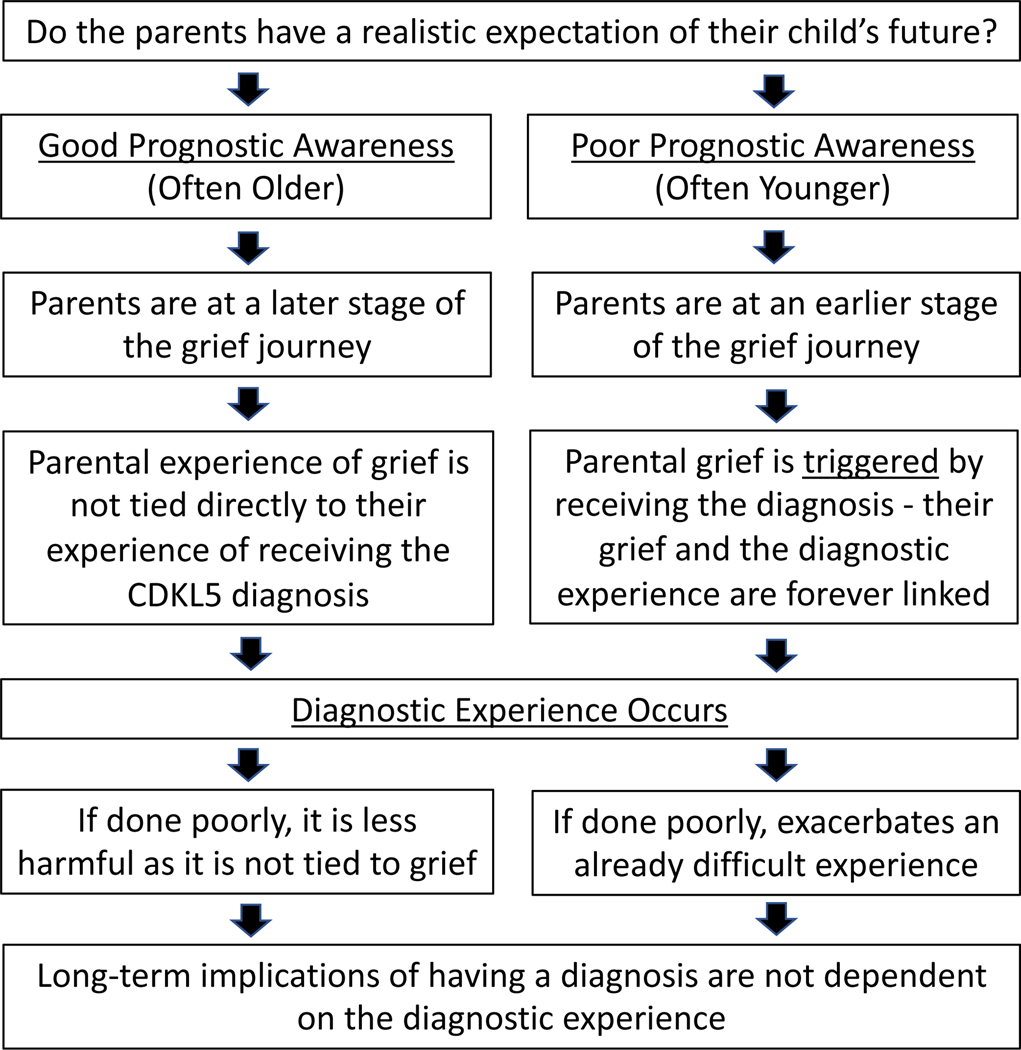

Themes are explored in 3 main categories: the emotional impact of receiving the diagnosis of CDD, parent’s perception of the diagnostic experience, and the implications of having a CDD diagnosis. An overall conceptual model generated from these findings is outlined in Figure 1—specifically, how realistic parents’ expectations are at the time of diagnosis (their prognostic awareness) and how this relates to the timing of their experience with grief and, additionally, that the diagnostic experience is not solely related to the emotions generated by the new diagnosis. Rather, that the way the news is provided can be done well or poorly regardless of the stage the parents are at in their grief journey. Many of the longer-term implications of having a diagnosis did not depend on the diagnostic experience or emotional impact of the diagnosis. Although the model is presented as being binary, there certainly is overlap and exceptions to this basic model.

Figure 1.

Depicts a conceptual framework for the relationship between age and parents’ perception of their child’s prognosis with the impact of receiving a diagnosis on those parents as well as how this relates to the way in which parents are informed of the diagnosis.

Emotional Impact of Receiving a Diagnosis of CDD

Grief is universal but not always associated with receiving the diagnosis.

Grief related to having a child with CDD was nearly universally expressed by parents. Although the grief expressed was multifaceted and varying, foundational to the grief was the disconnect between the parents’ expectations and imagined futures for their children and the reality of the disease. Parents expressed this disconnect in a variety of ways such as describing the disease as “stealing the child’s life,” or as an endless reminder of what could have been. This grief was often named directly as “grief” but at other times described as anger, sadness, shock, disbelief, or isolation.

Parents of children diagnosed at an older age expressed the grief as an episodic phenomenon often connected to significant milestones in life that were not achieved, such as first crawl, walk, speech, first day at school, turning 16, marriage, and so on. Often this grief was not specifically connected with receiving the actual diagnosis of CDD. For these parents of older children at the time of diagnosis, the diagnosis was often associated with a sense of relief or excitement, as they already possessed a clear sense of their child’s potential and likely future. In older children, the diagnosis often came at the end of a long diagnostic odyssey so that the relief and excitement was in response to finally receiving an answer or explanation after so many negative test results.

Grief is associated with the diagnosis when parents have poor prognostic awareness.

Prognostic awareness is how accurately a patient, or parent of a patient, understands the likely prognosis. Parents whose children were diagnosed younger often had poorer prognostic awareness and describe the diagnostic experiences as “shocking” or being “blindsided.” In this circumstance, parents often linked their grief directly with the moment they received the diagnosis of CDD as this was the first time they understood the gravity of their child’s condition, or the diagnosis cemented the severity they had feared. “Nothing’s gonna be the same. She’s my daughter. I’m not going to experience the joys that typical daughters get to experience with their mothers, like hair, nails. Barbies, dress up. . . . I guess I’m not saying its sadness of the disease, as much as sadness that this disease has taken my daughter from me in those ways” (participant 9). Parents of children diagnosed at a younger age expressed grieving episodically as well, but there was a more acute sense of grief on receipt of the CDD diagnosis (see Table 2). The age of the child at the time of diagnosis often played a role, presumably because developmental delays experienced by patients with CDD are not as obvious at a younger age contributing to poorer prognostic awareness.

Table 2.

Grief Association With the Diagnosis by Age at Diagnosis.

| Younger children at the time of diagnosis | Older children at the time of diagnosis |

|---|---|

|

Acute onset of grief at time of diagnosis “We had to go out to the car, and I had to Google this as we were driving home. It was on Googling it that I began to have any real inkling of how serious it was. I remember this was—sorry, I’m gonna cry now. It was December, and the appointment had been at the end of the day. It was daylight when we went in and dark when we came out. I just always felt this was some analogy of our life, that we just came out into the darkness. The first night was so bad. You just bring your child home, and all of a sudden, I felt very disconnected from her. I felt like I didn’t know who she was anymore. She was living, but her diagnosis felt like a death sentence to me. She was this living body and nothing else at the time. We just felt such desperation. We felt so low.” (participant 25) “I guess it was—I don’t know. You had hopes during your pregnancy and after she’s born. She’s born healthy, so you assume. You’re told that the seizures might go away, so you hold on to hope it will go away, and if nothin’ more, but then when you find out that there’s a diagnosis, and the blanket expectation of what CDKL5 was, all of our hopes and dreams felt like they were thrown away.” (participant 4) |

Episodic grief associated with life’s milestones

“We went through stages where we still have stages of grief as she gets older. She just had her 16th birthday. That was a really hard one for me. All the “should haves” always come back up, it seems, a lot around birthdays. ... I feel like I have this at every birthday but especially her 16th. We should have been going and getting her driver’s license, and we should be looking at colleges, and we should look at finding her prom dresses. Instead, we’re making sure her wheelchair fits or make sure her seizure meds are helping. You completely realize, over and over again, the reality of her life is never gonna be what we thought it was gonna be.” (participant 14) Grief prior to diagnosis and excitement at the time of diagnosis. “Well, like I said, this was a slow burn for us ... she’s premature and then she started having seizures and then we were concentrating on our therapy. Getting her back up to speed. Then, we were realizing she’s not caught up, which that was probably my plateau. She’s not caught up and she’s never going to be caught up. Starting with school and IEPs and things like that, that was—those were some of my grief times. My sadness times. Finding out that we had a specific name for what she has was pretty exciting. It really wasn’t sad for me. We worked through all of that. Seriously.” (participant 8) |

Prognostic awareness is influenced by the parental level of medical knowledge.

In addition to age, several other factors seemed to influence parents’ prediagnosis prognostic awareness. There were some parents that had a sense there was something serious going on even at an early age. “We had known that she had epilepsy ‘cause we had—we had a rocky start. From the beginning . . . She’s my fourth child. When she was born, I was concerned over the way that she was presenting” (participant 27). This parent also expressed that she was already grieving for her infant and the diagnosis just confirmed what she already knew. Some parents identified the diagnosis themselves through their own research and requested genetic testing that confirmed their suspicion. In these cases, parents had better prognostic awareness, and although there was still associated grief, it was not described as shocking.

Several parents also reported that they knew something was wrong, but either did not realize that epilepsy in infants could be associated with developmental delays or thought that everything would be okay if they could get the seizures under control. “With her seizures getting a little bit better . . . I really thought that she was getting better. Her neurologist at the time did not properly disabuse me of this idea. In hindsight, I think that the neurologist always knew that what was going on with my daughter was really serious, and she just wasn’t willing or able to be . . . upfront about it. . . . The idea that my daughter would be permanently and severely disabled just hadn’t crossed my mind. . . . I didn’t really understand that epilepsy is so linked with intellectual disability and developmental delay” (participant 25).

Feelings of confusion and isolation

Many parents also reported confusion around the time of the diagnosis often linked to not fully understanding the diagnosis. However, the confusion was not always associated with an overall perception of a negative diagnostic experience, particularly when grief was not as closely linked to receiving the diagnosis. For example, in parents of older patients there was confusion mixed with curiosity. Whereas some parents of younger patients described confusion mixed with irritation and hopelessness. Regardless of the emotional impact of receiving the diagnosis, for most parents there was a hunger for information that followed. Parents of both older and younger patients expressed disappointment around the time of diagnosis that there is no specific treatment for CDD. Of note, some parents expressed ambivalence to the actual diagnosis stating that “it doesn’t change who their child is.”

Similarly, many parents expressed deep feelings of isolation. Parents expressed feeling isolated from their providers, family, friends, or their affected child. Isolation did seem to relate to grief and was often described more intensely by parents of younger children. Parents of older children describing feelings of isolation more in relationship to having a child with CDD including the nature and stigma of the child’s disabilities not just an emotional impact of grieving.

Positive emotions: excitement, sense of clarity or relief with having a name, and relief of guilt.

Some parents expressed excitement with receiving a diagnosis as it meant that they now had an explanation for their child’s disability. This was described more prominently in parents of older children with very good prognostic awareness at the time of diagnosis and was sometimes described as following a prolonged diagnostic odyssey. However, parents of younger children also expressed a sense of validation because they knew there was something wrong. Often this validation was related to having a specific name for what was wrong. “So now this monster has a name. It’s got a name. It’s something I can investigate” (participant 52). Many participants reported finding relief in knowing what the cause was even though CDD is not treatable. “I can deal with just about anything, but if I don’t know what I’m dealing with, then I don’t know how to handle that. Okay, here’s what it is. Now I can research and now I can move forward” (participant 2). In other cases, excitement was related to having something specific to guide management and expectations.

Many parents expressed relief of guilt related to receiving the diagnosis. Mothers especially expressed relief of guilt as they had blamed themselves for their child’s condition, assuming their child’s medical problems resulted from something they did or did not do during pregnancy. This was seen across mothers of children of all ages at the time of diagnosis. Fathers expressed relief that their child’s disability was not because they did not provide or seek out a particular treatment, therapy, or opportunity.

Parents’ Perception of the Diagnostic Experience

Parents’ perception of how they were given the diagnosis was not specifically tied to whether a grieving process was initiated.

Parents expressed a range of experiences with the way they were informed of the diagnosis regardless of the emotional impact which was influenced by their prognostic awareness as discussed previously. Although none of the parents of older children at the time of diagnosis felt that they had a negative diagnostic experience overall, they were still able to point out both “good” and “bad” aspects of how they were told. Similarly, some parents who overall described a negative experience of receiving the diagnosis due to the emotional impact of the diagnosis itself reported that their providers were excellent at conveying the diagnosis.

Parents’ perspective of the diagnostic experience was not determined by the provider type or method of communication.

Parents reported a range of positive and negative experiences across all provider disciplines (geneticist, neurologist, genetic counselor, or general pediatrician), the provider’s level of knowledge about CDD or the length of relationship with the provider. Some parents expressed appreciation at being given the news over the phone and felt the provider knew that was appropriate, whereas others appreciated being told in person.

Factors that support a positive diagnostic experience.

Parents described multiple factors as important for having a positive experience, including establishing a rapport with the physician who had time to address parents’ needs in a manner that is honest, compassionate, and clear as to diagnosis, prognosis, and their own knowledge of CDD. Parents valued the provision of plain language information and the development of a plan for next steps and resources (Table 3).

Table 3.

Parents’ Perception of How They Were Told the Diagnosis.

|

Parents who felt their provider did a good job “I will say that the doctor who’d been following us since she started having the seizures ... she was young..., but she presented me with the diagnosis and she’d actually been on the CDKL5 website and printed out the parent handbook. She went through that with me from front to back, which took at least an hour. We reviewed all of the symptoms, which was—I mean, it was awful. It was devastating but it also made a lot of sense. . . . [I]t was nice just to have it all laid out. ... It was a rude awakening, but she also went through all the various treatments and therapies.... I was able to also connect with . . . [various] parent support group[s]. ... I feel like I had a really positive experience. I was able to come home and actually have some information when I had to break the news to my husband and other family members.” (participant 7) “He let us ask questions, and he let us ask as many questions as we wanted. He didn’t end the conversation. We did.” (participant 3) “He probably ended up staying later than he wanted to at work just to be able to talk to us together on the phone about it.... We ... [h] ad him on speaker. My husband and I were both there. ...I remember him being super tender. He did have just a very calm demeanor when he talked about it. He did say that he was so sorry, and this is not what we wanted to see come back on the genetic testing, that kind of stuff. ... He was fantastic. I just felt like he was our friend telling us.” (participant 3) “I remember looking at it, and it said epilepsy, encephalopathy. ... I said to her, ‘Does this mean that [she]’s going to present with those things?...’ This is her regular neurologist. She was like, ‘I’d like to think not.’ She was like, ‘But I don’t know. This is my first time that I’ve ever seen this diagnosis, so I’m gonna get her into genetics.’” (participant 27) “I thought that was very thoughtful cuz she ... gave me the next step. We’re gonna make an appointment. We’re gonna try this. . . . That was very encouraging.” (participant 32) |

Parent who felt their providers did a poor job “[The provider] was, like, ‘I’m sorry. I’m not feeling well today. I have to go. I came in just to see you,’ like I should be grateful for this amazing appointment.... Then, the neurologist who had stepped in and was like, ‘Do you have any questions?’ I was, like, ‘I don’t know [what to ask]. Is she going to walk or talk?’ She’s, like, ‘I just don’t know. You should find a community of parents who can help you.’ Then she also left the room. The appointment with the geneticist and the neurologist had gone so badly, the piece of paper we got with her actual diagnosis on it . . . said CDKL5, but because they scrawled “Rett-like” all over it in really big letters, I didn’t even realize that she had CDKL5, so I started Googling Rett. That’s how much I didn’t know. . . . For the first probably six hours, I was on Rett pages, and it was only as I was sitting there at midnight in my bed crying and rereading this diagnosis that I was, like, ‘Okay, there’s some other letters here I need to Google.’ That’s how little we had walked away from this appointment with.” (participant 25) “The geneticist was literally in the room for two seconds to tell me, ‘Okay, we’re just letting you know it’s CDKL5. There’s nothing we can do at this point for you. Here’s my card and if you need to call me this is my number.’ Then she walked out.” (participant 39) “I was in the hospital with her. . . . They [neurology team] were rounding [and] my husband had not gotten there yet. . . . The neurologist [accompanied by the rounding team] came in and said, ‘Hey, we found the reason for your daughter’s diagnosis. We’re not going to tell you about it now because it’s not associated with good things, and we don’t want you looking it up. It’s sort of like Rett syndrome, and somebody will come back and talk to you.’... At that point, everybody’s staring at me, and then . . . they all walk out. . . . I’m somewhat familiar with Rett syndrome.... I was really upset and ready to cry. ... I’m holding my [infant] daughter and just got really terrible news, and I don’t know anything about it, and I have no idea when I’m gonna get any information. ... I was completely overwhelmed.... I felt really scared and really sad. Angry, I was really angry in the moment of how they were delivering the diagnosis. I was like, ‘Are you kidding? Is this really how this is gonna happen?’ I don’t know what the right word is, but I just felt really small, like I don’t—there’s all these people watching me, and this is just not—I don’t want anybody to be here right now.” (participant 1008) |

Implication of Having a CDD Diagnosis

Although the focus of the interview was primarily related to the experience receiving the diagnosis, participants also described the impact of having a child with CDD on their family.

Having a child with severe disabilities impacts the whole family.

Several parents reported that having a child with severe disabilities brought them closer to their spouse, helped their other children to learn to be more compassionate people, made them more aware of differences and disabilities in general, and allowed them to have more gratitude for what they have in life. “There’s somebody right there who needs our help. Every single day we have an opportunity to help her and to do it graciously and to do it joyfully” (participant 30).

Others reported that having a child with disabilities created strain with family members outside their immediate family who do not seem to understand their situation. Additionally, several participants discussed the effects of caring for a child with severe disabilities and multiple medical needs on a whole family, including the amount of time and resources that this pulls from other family needs. This can be challenging for siblings of the affected child. One parent described that the family dynamic is “a little bit more child-centered [but] around one child” (participant 3).

Impact of diagnosis on access to services and connecting with a community.

Several parents mentioned that having a specific diagnosis (CDD) improved their ability to get services, such as therapies, and to advocate on behalf of their child. Other parents reported the diagnosis provided a reference to know what to expect and how to get the care their child needed, a “playbook.”

Finally, many participants described the benefits of connecting with the CDD community. “It’s just this amazing, remarkable shared experience like no one in the whole wide world” (participant 30). This included the emotional benefit of connecting with other individuals over a shared experience, but also had practical impacts such as “I’m having trouble with my feeding pump and I don’t know what to do . . . within five minutes, I’ll have 10 mothers telling me a couple different things and it’s fixed” (participant 9).

Comparison With Results From the International CDKL5 Disorder Database

A total of 345 families of children with CDD completed the diagnostic experience section of the questionnaire. Birth years ranged over a period of 40 years from 1981 to 2020, age at diagnosis ranged from 6 months to 35 years, and year of diagnosis from 2004 to 2020. Of the 345 children, 288 (83.5%) were female; 162 (47.0%) were from North America, 76 (22.0%) from Western Europe, 30 (8.7%) from Australia and New Zealand, and 77 (22.3%) from a range of other countries including Russia. Perceptions of diagnostic experience are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Nearly half (46.1%) of caregivers were satisfied with the way their child’s diagnosis was conveyed to them, 29.0% were dissatisfied, and 24.9% neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. Caregivers of children born 2015 or later (42.9%) were more dissatisfied with the way their child’s diagnosis was explained to them than those whose children were born prior to 2015 (23.5%). Similarly, those whose children were diagnosed after 2016 were more dissatisfied (50%) than those diagnosed previously (22.6%). Moreover, caregivers of those who were born from 1981 to 2010 (54.6%) were more satisfied than caregivers of those born subsequently (28.0%). Caregivers who received a diagnosis before 2012 (52.5%) were more satisfied than those who received a diagnosis later (31.3%). Just under one-third (30.3%) of caregivers were satisfied with the information they were provided about family support and resources, but 41.7% were dissatisfied and 28% neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

Of the 345 families, 250 provided comments in the open question section. We used these comments to identify a number of categories similar to those found in the qualitative component, for example, grief, emotional impact, perception of diagnostic experience, and implications of receiving diagnosis. As in the qualitative interviews, “grief” was specifically articulated by nearly a quarter (22.4%), although other terms included were “sadness,” “devastated,” “maternal depression,” and “being upset.” Grief was expressed more often by caregivers living in the United States than elsewhere. With respect to emotional impact, caregivers expressed feelings of positivity, neutrality, and negative emotions. Positivity was expressed using terms such as “relief,” “freedom from guilt,” and “ecstatic.” Caregivers of those born 1981–2005 expressed more positivity than those born in recent years as did those who were diagnosed after the age of 5 years who were also more likely than not to express neutrality about the diagnosis.

Caregivers also specifically expressed their perceptions of the diagnosis experience in the open text using positive terms coded as “encouraging” and “empathic” whereas negative terms included “poorly conveyed,” “misinformation,” “lack of information,” and “lack of counselling.” The percentage with a negative perception (37.6%) was higher than those with a positive perception (6%). Those diagnosed younger and those residing in Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand more often expressed a negative perception of the diagnostic experience.

Access to the International Foundation for CDKL5 Research (IFCR) website, Facebook groups, and building a community with other families were important benefits of receiving a diagnosis, which were expressed more by North American families than those from elsewhere. Another outcome raised by a small proportion (4.8%) of families was impact on nuclear and extended family. However, the benefits to other siblings in terms of building compassion and understanding of differences was not a theme seen in this data set.

Discussion

This study describes parents’ lived experience of receiving a diagnosis of CDD and importantly demonstrates that this experience can differ depending on the child’s age and the parents’ prognostic awareness at the time of diagnosis. Parents of older children or adults at the time of diagnosis reported generally positive (excitement, relief) or neutral (a feeling that the diagnosis did not really change things) diagnostic experiences. Although these parents often reported that they had experienced grief over the course of their child’s life, they did not associate this grief with receiving the diagnosis. Alternatively, many of the parents of younger children at the time of diagnosis had poor prognostic awareness as the extent of their child’s medical challenges was not as evident. For these parents, realization of the prognosis for their child was directly linked with receiving the CDD diagnosis, which then triggered a grieving process. Consistent with the literature, this study supports the concept that grief related to having a child with a severe disability is nearly universal, but also clarifies that this grief is not always connected in the parent’s mind to receiving the diagnosis.15,16,21 Although this finding is intuitive, it is also critical to recognize as technology and availability of genetic testing is facilitating diagnoses at young ages, including in the first year of life.22 There is a rich literature and increasing emphasis in medical training on how to convey serious news.8,23–27 This study identifies additional factors that may influence the diagnostic experience of receiving a life-altering genetic diagnosis like CDD.

In addition to the child’s age, several factors were identified that influenced whether parents had good prognostic awareness. Some parents had more medical knowledge or experience with infant development and were able to recognize the severity of the situation or even discover the diagnosis themselves. However, none of the parents mentioned feeling prepared for the diagnosis by their provider. However, several parents reported feeling misled that good control of their child’s seizures would result in a good prognosis. This is generally contrary to existing literature that suggests that there is a significant risk of intractable epilepsy and developmental challenges for all patients with onset of epilepsy in the first year of life.28 This suggests that there is a window of opportunity to prepare parents for the potential outcomes of genetic testing before ordering the genetic test, an essential goal of pretest genetic counseling.29 This includes expressing concern that their child may have a poor prognosis including significant disability. Many providers may feel that this could cause unnecessary worry for parents, which is a valid concern, but studies like ours suggest that families would often rather know when their providers are concerned.15,16 The themes identified through qualitative interviews were generally supported by the themes identified in the ICDD open-ended questions, and there seemed to be a similar difference in perception based on the age of the child at diagnosis. It was also worth noting that both qualitative methods found a subset of parents who expressed excitement around having found the answer. Very similar themes were uncovered in the larger international CDD data set, around the way news is provided to families and the benefits of having a diagnosis, suggesting that these findings may be broadly applicable across cultural and geographic boundaries.

There is a rich literature related to providers giving serious news, possibly the most pivotal study being the development of the SPIKES framework.8 SPIKES is an acronym for Setting, Patient’s Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Empathy and Strategy/Summary. Patient Perception is about determining what the patient (or parent) already knows or thinks about the situation.8 From this perspective, asking some probing questions prior to giving the diagnosis may be appropriate, particularly related to what the parents think is the developmental and neurologic prognosis for their child. This will allow the new diagnosis discussion to be catered to the parent’s current level of knowledge and prognostic awareness. Furthermore, the themes identified in this study reemphasize the importance of providers being empathic, having an appropriate setting, not being rushed, giving information in chunks, and using lay terminology.8,30–33 Publications from 2000 to 2019 have surprisingly similar themes relating to how serious news should best be provided. Future work needs to continue to focus on provider education around this critical issue.25,26,34 The themes identified here also extend on the recommendations of SPIKES and triangulate well with a recent survey assessing patient perspectives of receiving serious news from 1337 individuals.33 The survey identified 5 recommendations not covered by the SPIKES framework with clear relevance to genetic diagnosis based on this study’s results: (1) ensure a timely follow-up; (2) offer information sheets about the diagnosis; (3) provide contact information for support organizations; (4) provide contact information for counseling services; and (5) convey a sense of determination to aid the parent (patient) going forward.33 These recommendations would rationally address many of the concerns raised by families in our study.

The sense of isolation that patients or parents can have after receiving serious news can be highly impactful and may be even more likely in a rare disease. This can also impact future care if the patient or caregiver feels isolated or resentful of the care team. Having a plan, as suggested above, seemed to help reduce this sense of isolation for several participants. This study reiterates the findings that when serious news is first received, it can be difficult for individuals to take in additional information due to the emotional processing that is required.15,16 A recent pilot study of a 2-tiered appointment process proved helpful for individuals receiving a new diagnosis of motor neuron disease.35 In this model, the initial visit focuses on the most basic and general concepts with a focus on emotional support for the individuals involved. The second visit that occurs shortly after the first provides additional details and plans, after individuals have had time to process the new life-changing information. This model may be useful for genetic diagnosis as there are many highly technical concepts to discuss related to recurrence risk, penetrance, family planning, and possibly even treatment that may be hard for families to absorb during an initial visit.

Longer-term implications of having the diagnosis of CDD were seen as valuable and confirm previous findings related to the ability to access services and having guidance about care.16 This study found a consistent theme related to the value parents had derived from CDD patient advocacy groups both in terms of practical information and a sense of community with others who understand what they are experiencing. This further supports the importance of genetic testing, even for conditions that are not directly treatable such as CDD. This study does not argue that early diagnosis is a problem. On the contrary, this is an inevitability of improved technology and certainly necessary for improved implementation of burgeoning precision treatments.7,22 However, this study does highlight that providers need to convey a new diagnosis in a way that is sensitive to the parents’ prognostic awareness at the time of that diagnosis and the importance of using frameworks such as SPIKES for providing serious news.

The in-depth findings from the qualitative interviews may not be experienced by all parents receiving a CDD or other similar genetic diagnosis. The participants of this study were skewed toward white, affluent mothers, which may have precluded the identification of additional themes that may be more important in other groups that are less well represented in our interviews. Therefore, caution is necessary in generalizing these qualitative results. However, a fairly large sample was collected, particularly for a rare disease, and the themes identified triangulate with the existing quantitative and qualitative literature and are supported by the findings from the ICDD that included responses from 250 international participants. The data from the ICDD questions also suggest there are likely some cultural differences that are important to explore though that data set does not provide the same depth of analysis as the interview format. Nonetheless, future research should make efforts to ensure that minority groups with potentially different cultural perspectives as well as lower socioeconomic and educational levels are well represented among participants. Finally, although this study was dedicated to the diagnosis of CDD specifically, the findings converge well with the existing literature and are likely more generalizable particularly to other early-life genetics syndromes with profound impacts on affected individuals.

Conclusion

This study is the first description of the parents’ experience of receiving a diagnosis of CDD for their child. It demonstrates that this experience can be very different based on the parent’s prognostic awareness at the time of diagnosis and that this is heavily, but not solely, related to the age of the child at the time of diagnosis. Participants’ experiences reinforce existing literature around the use of frameworks like SPIKES to help give serious news well, which is informed by identification of the factors determining whether parents will see a new diagnosis as “bad news” at the time of diagnosis. It is increasingly important that providers give new diagnoses in ways that form a partnership with families both to support them through the implications of the diagnosis and to ensure a functional patient physician relationship with the ability to support the increasingly complicated treatment decisions for precision therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Gina Vanderveen supported the operational needs for this study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the International Foundation for CDKL5 Research.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SD has consulted for Upsher-Smith, Biomarin, Neurogene, Marinus, and Ovid Therapeutics; he has funding from the NIH, International foundation for CDKL5 research, project 8P and Mila’s Miracle Foundation; and he also serves on the advisory board for the nonprofit foundations SLC6A1 Connect, Ring14 USA, and FamilieSCN2A. HL and JD have consulted for Avexis, Anavex, GW Pharma, and Newron on unrelated subject matter. They have both consulted for Marinus and Ovid Therapeutics on related subject matter. HL is currently funded by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (no. 1117105). Both HL and JD have funding from the NIH and Marinus related to this subject matter. AD is currently an employee of Merck. This research was completed while AD was an employee of the University of Colorado. Merck played no role in the research. TAB received funding from the Ponzio Family Chair in Neurology Research/Children’s Hospital Colorado Foundation. Clinical trials sponsored by Rett Syndrome Research Trust, Neuren, Acadia, Ovid, and Marinus. He has consulted for RettSyndrome.org, AveXis, Ovid, Takeda, Taysha, Alcyone, and Marinus. Additional unrelated funding support from NIH, CURE, GRIN2B Foundation, and Simons Foundation.

Footnotes

LT, MF, and MM have no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Weaving LS, Christodoulou J, Williamson SL, et al. Mutations ofCDKL5 cause a severe neurodevelopmental disorder with infantile spasms and mental retardation. Am J Human Genet. 2004; 75(6):1079–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Rosas-Vargas H, et al. Key clinical features to identify girls with CDKL5 mutations. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 10):2647–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fehr S, Wilson M, Downs J, et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(3):266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fehr S, Leonard H, Ho G, et al. There is variability in the attainment of developmental milestones in the CDKL5 disorder. J Neurodev Disord. 2015;7(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehr S, Downs J, Ho G, et al. Functional abilities in children and adults with the CDKL5 disorder. Am J Med Genet A. 2016; 170(11):2860–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demarest ST, Olson HE, Moss A, et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: relationship between genotype, epilepsy, cortical visual impairment, and development. Epilepsia. 2019;60(8):1733–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demarest ST, Brooks-Kayal A. From molecules to medicines: the dawn of targeted therapies for genetic epilepsies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(12):735–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP.SPIKES—a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedrichsen MJ, Strang PM, Carlsson ME. Breaking bad news in the transition from curative to palliative cancer care--patient’s view of the doctor giving the information. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8(6):472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bousquet G, Orri M, Winterman S, Brugiere C, Verneuil L, Revah-Levy A. Breaking bad news in oncology: a meta-synthesis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(22):2437–2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barke J, Coad J, Harcourt D. Parents’ experiences of caring for a young person with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1): a qualitative study. J Community Genet. 2016;7(1):33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somanadhan S, Larkin PJ. Parents’ experiences of living with, and caring for children, adolescents and young adults with mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11(1):138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bose M, Mahadevan M, Schules DR, et al. Emotional experience in parents of children with Zellweger spectrum disorders: a qualitative study. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2019;19:100459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitehead LC, Gosling V. Parent’s perceptions of interactions with health professionals in the pathway to gaining a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis (TS) and beyond. Res Dev Disabil. 2003; 24(2):109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivard MT, Mastel-Smith B. The lived experience of fatherswhose children are diagnosed with a genetic disorder. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(1):38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashtiani S, Makela N, Carrion P, Austin J. Parents’ experiences of receiving their child’s genetic diagnosis: a qualitative study to inform clinical genetics practice. Am J Med Genet. 2014;164a(6):1496–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sokolowski R. Introduction to Phenomenology. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard H, Junaid M, Wong K, Demarest S, Downs J. Exploring quality of life in individuals with a severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Epilepsy Res. 2021;169:106521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glenn AD. Using online health communication to manage chronic sorrow: mothers of children with rare diseases speak. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truty R, Patil N, Sankar R, et al. Possible precision medicine implications from genetic testing using combined detection of sequence and intragenic copy number variants in a large cohort with childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia Open. 2019;4(3):397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Supe AN. Interns’ perspectives about communicating bad news to patients: a qualitative study. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24(3):541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw J, Dunn S, Heinrich P. Managing the delivery of bad news: an in-depth analysis of doctors’ delivery style. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(2):186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dadiz R, Spear ML, Denney-Koelsch E. Teaching the art of difficult family conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(2):157–161.e152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross MK, Doshi A, Carrasca L, et al. Interactive palliative and end-of-life care modules for pediatric residents. Int J Pediatr. 2017;2017:7568091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronen GM, Kraus de Camargo O, Rosenbaum PL. How can we create Osler’s “great physician”? fundamentals for physicians’ competency in the twenty-first century. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(3):1279–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg AT, Wusthoff C, Shellhaas RA, et al. Immediate outcomes in early life epilepsy: a contemporary account. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;97:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayres S, Gallacher L, Stark Z, Brett GR. Genetic counseling in pediatric acute care: reflections on ultra-rapid genomic diagnoses in neonates. J Genet Couns. 2019;28(2):273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCulloch P. The patient experience of receiving bad news from health professionals. Prof Nurse. 2004;19(5):276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasanpour M, Sadeghi N, Heidarzadeh M. Parental needs in infant’s end-of-life and bereavement in NICU: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2016;5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira MUL, Goncalves LLM, Loyola CMD, et al. Communication of death and grief support to the women who have lost a newborn child. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2018;36(4):422–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirza RD, Ren M, Agarwal A, Guyatt GH. Assessing patient perspectives on receiving bad news: a survey of 1337 patients with life-changing diagnoses. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(1):36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorniewicz J, Floyd M, Krishnan K, Bishop TW, Tudiver F, Lang F. Breaking bad news to patients with cancer: a randomized control trial of a brief communication skills training module incorporating the stories and preferences of actual patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):655–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seeber AA, Pols AJ, Hijdra A, Grupstra HF, Willems DL, de Visser M. Experiences and reflections of patients with motor neuron disease on breaking the news in a two-tiered appointment: a qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9(1):e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.