Abstract

Employing the stressor-strain-outcome framework, this study demonstrates that COVID-19 information overload on social media exerts a significant effect on the level of fatigue toward COVID-19-related messages. This feeling of message fatigue also makes people avoid another exposure to similar types of messages while diminishing their intentions to adopt protective behaviors in response to the pandemic. Information overload regarding COVID-19 on social media also has indirect effects on message avoidance and protective behavioral intention against COVID-19, respectively, through the feeling of fatigue toward COVID-19 messages on social media. This study emphasizes the need to consider message fatigue as a significant barrier in delivering effective risk communication.

Keywords: Message fatigue, Risk communication, Information overload, Message avoidance, Behavioral intention

Introduction

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020, has brought many unexpected negative impacts and disrupted our daily lives in various aspects including physical and mental health, economy, education, and social lives (Atalan, 2020; Cao et al., 2020; Daniel, 2020; Prime et al., 2020). Driven by the need to protect public health and slow down the transmission of deadly virus, several governments around the world had placed on lockdown and imposed restrictions on mobility and social activities. These restrictions brought higher levels of social media consumption as some individuals regarded them as the only tool to relieve their feeling of isolation during long-term social distancing (Valdez et al., 2020).

In response to the global public health emergency, effective and appropriate risk communication has been emphasized to stop spreading the deadly virus around the world. The WHO (2022a) defines risk communication as “the real-time exchange of information, advice, and opinions between experts or officials and people who face a threat (from a hazard) to their survival, health or economic or social wellbeing” (para., 1). Risk communication has been used to disseminate accurate and timely information to the public about health risks and natural disasters (e.g., a disease outbreak) and instruct people on how to reduce the risks and protect themselves (WHO, 2022a).

In the past decade or so, social media channels have become beneficial and critical for risk communication. Social media allow public health institutions and news media outlets to convey health-related messages to a variety of audiences, share them on multiple platforms at once and receive real-time feedback from the public (Heldman et al., 2013). In this regard, social media can be expected to play an important and positive role in risk communication, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite these advantages of social media in risk communication, such as immediate and widespread information sharing, extremely repetitive exposure to messages about a health risk or disease on social media may create cognitive overload and further provoke negative reactions from users. This phenomenon can be explained by a cognitive load theory arguing that people experience heavy cognitive load when demanded to process a task or information that exceeds their capabilities, thereby leading to negative outcomes (Sweller, 1988). One major negative reaction is a sense of fatigue (Bright et al., 2015). Indeed, when receiving too many or repeated messages about the same topic through social media, people become mentally exhausted or feel fatigued by the messages (Dhir et al., 2018). Further, this reaction can negatively influence the persuasion effectiveness of the messages by bringing resistance and ineffective outcomes such as avoiding similar-themed messages and diminishing motivations to behave in reducing the risk (Guo et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2016).

As one of the possible dark sides of social media in risk communication, examining this feeling of fatigue toward health-related messages on social media is warranted. To date, several studies have demonstrated that repeated exposure to social media messages is related to health-related risks such as obesity (Kim & So, 2018), tobacco (So & Popova, 2018), and unprotected sex (Robinson et al., 2003) causing a sense of fatigue. As the pandemic lasts more than two years, COVID-19-related messages continue to pour in, and people keep receiving those messages on social media. The exposure to similar types of messages has partially to do with social media algorithms that push popular messages to the top of their news feeds. The more people share and comment on certain messages, the messages will keep showing up on individual news feeds. Therefore, social media users may feel fatigued by similar kinds of COVID-19-related messages that constantly reappear on their feeds.

Concerning this phenomenon, to our best knowledge, few studies have examined message fatigue about COVID-19 on social media. For example, Liu et al. (2021) examined how COVID-19 information overload influences social media users’ psychology and behaviors during the pandemic, especially among Gen Z. The authors demonstrated that Gen Z in the United Kingdom showed higher levels of social media fatigue when they encountered an enormous volume of COVID-19 messages (i.e., higher level of information overload), which increased intention to discontinue their social media use. However, their study examined psychological distress – fatigue – toward social media platforms rather than focusing on the content or messages about COVID-19 shared on social media.

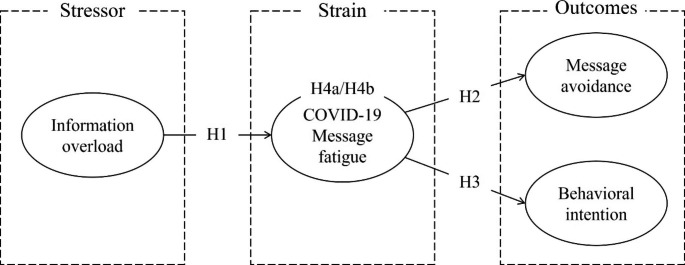

The present study seeks to demonstrate COVID-19 message fatigue on social media empirically and its relevant factors for the following purposes. First, our overarching goal is to understand the potential downside of social media use in risk communication. Second, we seek to extend the stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) framework by Koeske and Koeske (1993), to the context of COVID-19 message fatigue on social media by identifying significant and relevant factors. Specifically, we propose information overload as a stressor (S), COVID-19 message fatigue as a strain (S), and information avoidance and intentions for protective behaviors against COVID-19 as outcomes (O). We expect this study will contribute to developing a theoretical model of message fatigue on social media and its meaningful outcomes.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Risk communication and role of social media

Risk communication was introduced in response to health risks and environmental disasters (e.g., earthquakes, tornados, and hurricanes) in the late 20th century. No matter what kind of risks we encounter, effective risk communication is necessary to handle such risks efficiently and to prevent potential disasters in the future. In the past decades, scholars have studied the roles of risk communication and its effectiveness. Effective risk communication should be simple and clear, and provide reasonable solutions (Freimuth et al., 2000). Also, it should be aimed at influencing people’s perceptions about the risk and/or encouraging behavioral changes to protect themselves (Heath & O’Hair, 2008; Reynolds & Seeger, 2005; Visschers et al., 2009).

Regarding COVID-19, robust and effective risk communication is necessary around the world to reduce the spread of virus. Indeed, the WHO (2022b) updated checklists for risk communication and community engagement (RCCE). It was a call for countries across the world to prepare for the outbreak, how to respond to COVID-19 and implement effective risk communication strategies that would help reduce the public health risk. The RCCE checklist was composed of goals (e.g., develop, build, and maintain trust with the public through ongoing two-way communication) and actions (e.g., risk communication system, public communication).

Earlier, scholars argued that the “technocratic approach” which considers risk communication as a one-way linear process was inadequate to achieve effective risk communication (Grabill & Simmons, 1998). Instead, risk communication should be participatory. The use of social media makes it possible to break down the linear process. Wendling et al. (2013) argued social media allow users to actively engage in discussions, and information circulates and spreads very quickly, which in turn improves the effectiveness of risk communication. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, social media became the main information source for many and played a significant role in rapidly disseminating information about the pandemic and increasing risk awareness (Chan et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Malecki et al., 2020). While the aforementioned studies pointed out the positive role of social media in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, they overlooked the negative aspects of social media, namely, message fatigue about COVID-19 on social media. An enormous amount of COVID-19 information has been generated and shared on social media, which has overwhelmed information receivers (i.e., high levels of information overload), consequently leading to negative impacts on their psychological well-being (Islam et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021).

However, message fatigue related to COVID-19 on social media has not been extensively examined. Moreover, due to the unexpected outbreak of COVID-19, studies thus far have yet to explain the predictors and outcomes of COVID-19 message fatigue and to propose psychological mechanisms behind social media use in risk communication. Thus, drawing upon the stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) approach, the present study investigates how overexposure to information about COVID-19 on social media influences message fatigue. Further, we examine impacts of this psychological fatigue by focusing mainly on avoidance of the COVID-19 messages and motivations for protective behaviors against COVID-19.

A stressor-strain-outcome model

We adopt the stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) framework developed by Koeske and Koeske (1993) to identify possible predictors and consequences of COVID-19 message fatigue on social media. Koeske and Koeske (1993) first proposed the SSO framework to explain the burnout phenomenon in workplaces assessing the relationship between mental conditions (e.g., stress and emotional exhaustion) and professional performances (e.g., job satisfaction and personal accomplishment), which was mediated by emotional states (e.g., burnout). They found a significant process between stress and work performance, thereby providing a empirical basis for conceptualizing the process of stress, strain, and outcome.

This SSO framework consists of three principal variables: namely, stressor (unpleasant and irritating environmental stimuli), strain (emotional exhaustion caused by the stimuli), and outcome (psychological or behavioral reactions) (Koeske & Koeske, 1993). This model suggests the stressor(s) directly leads to strain which has a direct influence on the outcome as follows: stressor → strain → outcome. In other words, strain mediates the relationship between stressor and outcome, being a significant effect of the perceived stressor and a predictor of outcome.

Previous studies have widely adopted the SSO framework to investigate negative aspects of communication technologies (e.g., Cao et al., 2018; Dhir et al., 2018, 2019; Guo et al., 2020; Luqman et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Yu et al. 2019; Zhang et al., 2016). For example, Cao et al. (2018) explored antecedents and outcomes of problematic social media usage through the SSO framework. Particularly, they regarded excessive social media use as a stressor; life invasion, technology exhaustion, and privacy invasion as strain factors, and academic performance as an outcome. Similarly, Guo et al. (2020) adopted the SSO model to understand message avoidance behavior in social media usage. The results demonstrated individuals who were exposed to irrelevant information and had higher levels of information overload and social overload were more likely to feel fatigued toward social media, and this psychological reaction increased information avoidance behavior. The authors, therefore, could support the SSO framework’s applicability in examining negative aspects of social media use. Based on these previous findings, the present research also applies the SSO framework to understanding COVID-19 message fatigue on social media. We explain each component of the SSO model applied to the context of this study in the following.

Stressor: information overload

People use social media for many different reasons. Some primarily use social media to seek information such as news and share it with others (Whiting & Williams, 2013). That is, many individuals use social media as a primary information source nowadays. However, as social media have become pervasive and more people depend on them as information sources, an extensive amount of information has been generated and shared by social media users. Too much information can cause people to feel overwhelmed and overloaded. Indeed, Zhang et al. (2016) found that people tend to become stressed when receiving an overwhelming amount of information on social media. Regarding this tendency, the phenomenon of information overload has gained academic attention as people are exposed to abundant information on social media that exceeds their cognitive ability for information processing (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; (A. R. Lee et al., 2016, 2017).

Information overload is closely associated with negative psychological or emotional reactions. Recent studies have demonstrated more people have experienced increasing levels of fatigue on social media due to the overwhelming amount of information exposure. For example, Zhang et al. (2020) examined the effects of information overload on social fatigue and found that people were more likely to feel fatigued when experiencing higher levels of information overload. Similarly, in Shi et al.’s (2020) study, information overload predicted social media exhaustion and fatigue, indicating that individuals with an excessive amount of information exposure tended to feel emotional exhaustion. These studies suggest that perceived information overload plays a significant role as a stressor. Hence, we also expect that perceived information overload caused by COVID-19-related messages on social media would be a significant stressor of COVID-19 message fatigue.

Strain: message fatigue

Message fatigue refers to a state of being tired and exhausted from prolonged exposure to similar-themed or/and redundant messages (Frew et al., 2013; Kinnick et al., 1996; So et al., 2017). There are several conditions that people tend to feel fatigued toward a certain message as follows: (a) when being exposed to a similar message frequently exceeding their desired levels (perceived overexposure), (b) when receiving repetitive messages (perceived redundancy), (c) when being mentally burned out in receiving the messages (exhaustion), or (d) when being bored on a given topic of the messages (tedium) (So et al., 2017). Based on the previous studies, we conceptualize COVID-19 message fatigue as an internal state of being bored and exhausted from the overwhelming amount of repetitive messages relating to COVID-19.

Drawing on the SSO framework, many researchers have examined fatigue as a significant strain and empirically demonstrated a positive relationship between perceived information overload and psychological fatigue. For example, A. R. Lee et al. (2016) considered information overload as one of the significant determinants of fatigue on social media and found that individuals with higher levels of perceived information overload tended to feel fatigued toward social media. Hwang et al. (2020) similarly observed that perceived information overload positively influenced cognitive fatigue when using instant messaging. In line with these previous findings, we also regard COVID-19 message fatigue on social media as one of the major strains caused by higher levels of perceived information overload. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1

Perceived information overload of COVID-19 messages is positively related to COVID-19 message fatigue.

Outcome: message avoidance and behavioral intention

Based on the terminology of advertising avoidance (Cho, 2004; Guo et al., 2020) defined the term message avoidance as “a kind of passive behavior in which users consciously ignore some information and avoid some friends’ information due to lack of time, energy, knowledge, or personal interest” (p. 2). This behavior can occur as one of the prominent effects of message fatigue. More people exhibit avoiding another exposure to similar-themed messages on social media (Kinnick et al., 1996; So et al., 2017). That is, message fatigue caused by information overload can influence message avoidance behavior.

Several studies have identified message fatigue results in message avoidance behavior. For instance, Kinnick et al. (1996) mainly focused on message fatigue toward social problems discussed on social media and found that people who received redundant and predominant messages relating to the problems tended to avoid content about a similar issue. Similarly, So and colleagues (2017) also demonstrated that message fatigue on health-related messages was positively related to message avoidance, indicating that individuals with high levels of fatigue toward the messages on social media tended to avoid another exposure to the same kinds of messages. As one of the outcomes of COVID-19 message fatigue, we hypothesize that individuals who feel this kind of fatigue would be more likely to avoid incoming similar messages on social media:

H2

COVID-19 message fatigue is positively related to COVID-19 message avoidance behavior.

Along with message avoidance, negative psychological and emotional reactions toward a message reduce its effectiveness (Shi & Smith, 2016). That is, message fatigue can reduce receivers’ motivations to engage in behaviors (i.e., behavioral intention) suggested by the messages. As an important component of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), behavioral intention refers to the motivations that influence the likelihood of performing a given behavior; the stronger the intention to perform the behavior, the more likely the behavior will be actually performed (Ajzen, 1991).

Previous studies have demonstrated the relationship between fatigue toward a given topic and behavioral intentions. For example, Kim and So (2018) examined anti-obesity messages and their negative effects on intentions to adopt healthy behaviors promoted in those messages. Their experimental results showed that fatigued individuals with anti-obesity messages were less likely to follow certain recommended behaviors of the messages such as using small plates. Similarly, Reynolds-Tylus et al. (2021) identified a negative association between fatigue towards similar messages and participants’ intentions to perform behaviors recommended in those messages.

Message fatigue diminished behavioral intentions to adopt advocated behaviors in the messages through psychological reactance (Brehm& Brehm,1981). With the same logic, we suggest that COVID-19 message fatigue would reduce behavioral intentions to perform protective behaviors against COVID-19 such as washing hands frequently, wearing facial masks, social distancing, quarantining when feeling sick, or getting vaccinated. Indeed, recent studies directly examined how COVID-19 message fatigue was related to preventive behavioral intentions. For example, Guan et al. (2022) found that as individuals were tired of having COVID-19 messages, they were less likely to follow the behaviors such as wearing masks and washing their hands. Hence, we propose:

H3

COVID-19 message fatigue is negatively related to behavioral intentions for protective behaviors against COVID-19.

The mediating role of COVID-19 message fatigue

Based on the literature review and the SSO framework, it is expected that COVID-19 message fatigue may play a mediating role between perceived information overload and COVID-19 message avoidance behavior, and between perceived information overload and behavioral intention, respectively. This study investigates whether COVID-19 message fatigue would become a mediator, as perceived information overload could bypass COVID-19 message fatigue and directly lead to COVID-19 message avoidance and/or behavioral intentions against COVID-19. It is possible that social media users directly avoid messages related to COVID-19 and/or are less likely to follow protective behaviors when they are overwhelmed by the amount of information about COVID-19. S. Lee et al. (2016) showed perceived news information overload directly led to news avoidance behavior. Thus, information overload of COVID-19 messages can directly induce individuals’ message avoidance and/or reduce behavioral intentions for protection. We thus propose:

H4a

COVID-19 message fatigue mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and COVID-19 message avoidance.

H4b

COVID-19 message fatigue mediates the relationship between perceived information overload and behavioral intentions for protection against COVID-19.

Taken together, based on the SSO framework and the existing literature, this study proposes the following theoretical model examining relationships between perceived information overload, COVID-19 message fatigue, message avoidance, and behavioral intention (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of this study based on the SSO framework

Method

Participants and procedure

The research was approved by the IRB at the authors’ institution at the time of data collection. An online survey hosted on Qualtrics was implemented to test the proposed model and hypotheses of this study. Participants who were over the age of 18 and social media users were recruited from the departmental research pool at a large Southwestern university in the United States. College students were mainly targeted because young adults aged between 18 and 29 years old spent the largest amount of time on social media (Pew Research Center, 2019). The survey took approximately 15–20 min to complete. The participants were given course credits for their completion. We could collect 478 responses. Of them, 31 responses were discarded from the data because there were too many items unanswered, and the final sample size became 447 (Mage = 19.73; Age ranged from 18 to 32 years). Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants (N = 447)

| Measure | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 181 | 40.5% |

| Female | 262 | 58.6% | |

| Non-binary | 4 | 0.9% | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 326 | 72.9% |

| Hispanic | 37 | 8.5% | |

| African American | 17 | 3.8% | |

| Native American | 9 | 2.0% | |

| Asian | 41 | 9.2% | |

| Multiethnic | 17 | 3.8% | |

| Average daily time | < 1 h | 20 | 4.5% |

| spent on SNS usage | 1–2 h | 109 | 24.4% |

| 2–3 h | 157 | 35.1% | |

| > 3 h | 161 | 36.0% |

Data analysis

Data were analyzed utilizing SPSS 28.0 and AMOS 24.0. We first examined multivariate normality and then descriptive statistics analysis was conducted to examine the characteristics of the sample and major variables of the present study. For a multivariate normal distribution, skewness, kurtosis, and outliers were evaluated based on the following criteria: values of skewness ranged between − 2 and + 2, and values of kurtosis ranged between − 7 and + 7 when utilizing SEM (Hair et al., 2010). Then, as a preliminary analysis, we calculated Pearson’s correlation to examine the intricate relationships between the variables of this study.

We also examined the reliability, convergent and discriminant validity of each construct based on the criteria suggested by scholars (Fornell & Lacker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010; Henseler et al., 2015). Specifically, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) were tested for scale reliability. If their values are greater than 0.70, then we concluded the scale was reliable. Convergent validity was tested by using average variance extracted (AVE), of which the value should be greater than 0.50 to be regarded as sufficient. The discriminant validity of the constructs was evaluated with the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, and the cut-off value was lower than 0.90.

Further, structural equation modeling (SEM) procedure using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was conducted. We first tested the measurement model by using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and then conducted SEM to test the hypothesized structural associations among the variables of this study. In line with Hu and Bentler’s (1999) suggestion, the following multiple indices were used to evaluate fitness of the model to the data: chi-square statistic (χ2), χ2/df ratio, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square (SRMR). The goodness-of-fit was determined based on the following criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999): χ2/df < 3, CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.08. All the estimates were indicated in standardized scores.

Measures

Information overload (IO). The IO scale developed by Karr-Wisniewski and Lu (2010) was used to measure the participants’ perceived level of information overload on social media. The scale consisted of three items (e.g., “I am often distracted by the excessive amount of information in social media”). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores on these items represented feeling higher levels of information overload on social media.

COVID-19 message fatigue. Fatigue toward COVID-19 messages was assessed using the message fatigue scale developed by So et al. (2017). This scale was originally developed to measure the level of fatigue about anti-obesity and safe sex messages, including 17 items with four dimensions (i.e., overexposure, redundancy, exhaustion, and tedium). Since the present study focused on fatigue toward COVID-19 messages on social media, we modified the scale by mostly replacing the word, safe sex/obesity with COVID-19. Due to the similarly worded items between the measurements of information overload and COVID-19 message fatigue and potential overlap between the two constructs, only two dimensions – exhaustion (4 items; e.g., “I am burned out from hearing that unprotected COVID-19 is a serious problem”) and tedium (4 items; e.g., “Health messages about COVID-19 are boring”) – dimensions were included in the main analysis for COVID-19 message fatigue. That is, we conducted a second-order factor analysis with exhaustion and tedium dimensions. Based on the results of the reliability and validity tests of this scale, we removed an item (i.e., exhaustion – item #4) that violated the criteria of validity (i.e., low factor loading). Higher scores indicated higher levels of feeling fatigued about COVID-19 messages on social media.

Message avoidance. Avoiding behavior of COVID-19 messages was assessed using the message avoidance scale which was originally developed to measure advertising avoidance on the Internet (Cho, 2004; Shin & Lin, 2016). For the present study, we replaced the word, advertising with COVID-19 messages on social media. The scale consisted of 4 items (e.g., “I intentionally ignore some messages about COVID-19 on social media”). The items were scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) with more avoidance of COVID-19 information on social media corresponding to higher scores.

Behavioral intention. Fifteen kinds of behaviors were included to measure one’s intention to engage in protective behaviors against COVID-19. These behaviors were suggested by the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. Respondents were asked to indicate the likelihood of following these actions on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores represented a higher likelihood to perform preventive actions against COVID-19. Example behaviors included in the scale were: wearing a mask or cloth in public areas, avoiding mass gatherings (more than 10 people), and using hand sanitizer.

Since this scale of behavioral intention had not been tested before, both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted for testing reliability and validity. According to the results of EFA, four items (i.e., BI4, BI9, BI12, and BI14) had lower factor loadings (< 0.40) and thus they were removed from the remaining analyses (Hair et al., 2010). The EFA also showed that 11 items loaded on three factors, and we named them as follows: (a) hygiene, (b) social restrictions, and (c) vaccination. We further conducted a three-factor second-order CFA to check the validity and found that the unifying second-order factor had an acceptable model fit: χ2(40) = 153.42, p < .001, χ2/df = 3.84, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.06 and SRMR = 0.04.

Results

Preliminary analyses

A summary of descriptive statistics and Pearson’s r correlation analyses among major variables of this study are indicated in Table 2. We concluded that the data were normally distributed in that values of skewness ranged between − 0.72 and − 0.07 and kurtosis ranged between − 0.91 and 0.45. As shown in Table 2, information overload was positively correlated with both COVID-19 message fatigue (r = .23, p < .001) and message avoidance (r = .45, p < .001) while being negatively correlated with intentions to perform protective behaviors against COVID-19 (r = − .33, p < .001). COVID-19 message fatigue was positively correlated with message avoidance (r = .63, p < .001) and negatively correlated with intentions to perform the recommended behaviors (r = − .51, p < .001). Finally, message avoidance was negatively correlated with behavioral intentions (r = − .53, p < .001). The results of this correlational analysis provided a solid basis for SEM.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation between variables (n = 447)

| Variables |

M

(SD) |

Skewness (Kurtosis) |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Information overload | 3.35 (0.83) |

− 0.57 (0.14) |

- | |||

| 2 | COVID-19 message fatigue | 4.28 (1.64) |

− 0.08 (-0.89) |

0.23*** | - | ||

| 3 | Message avoidance | 4.24 (1.68) |

− 0.13 (-0.94) |

0.45*** | 0.63*** | - | |

| Exhaustion |

4.37 (1.77) |

− 0.14 (-1.03) |

0.22*** | 0.61*** | - | − 0.51*** | |

| Tedium |

4.30 (1.66) |

− 0.06 (-0.78) |

0.23*** | 0.59*** | - | − 0.51*** | |

| 4 | Behavioral intention | 5.21 (1.29) |

− 0.86 (0.41) |

− 0.33*** | − 0.51*** | − 0.53*** | - |

| Hygiene |

5.65 (1.39) |

-1.32 (1.42) |

− 0.30*** | − 0.32*** | − 0.40*** | - | |

| Social restriction |

4.91 (1.51) |

− 0.59 (-0.38) |

− 0.30*** | − 0.56*** | − 0.53*** | - | |

| Vaccination |

5.05 (1.76) |

− 0.75 (-0.47) |

− 0.24*** | − 0.36*** | − 0.40*** | - |

Note. ***p < .001

Individual item reliability, internal consistency reliability, and convergent validity of the measurements were assessed by the AVE, CR, and Cronbach’s α. As indicated in Table 3, we confirmed that each construct was reliable and valid for further analyses.

Table 3.

Results of reliability and convergent validity tests

| Items | Factor loading | α | CR | AVE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information overload (IO) | IO1 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.51 | ||

| IO2 | 0.77 | ||||||

| IO3 | 0.63 | ||||||

| COVID-19 Message fatigue (MF) | Exhaustion | MF1 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.76 | |

| MF2 | 0.94 | ||||||

| MF3 | 0.93 | ||||||

| MF4 | 0.71 | ||||||

| Tedium | MF5 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.80 | ||

| MF6 | 0.91 | ||||||

| MF7 | 0.92 | ||||||

| MF8 | 0.85 | ||||||

| Message avoidance (MA) | MA1 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.76 | ||

| MA2 | 0.96 | ||||||

| MA3 | 0.88 | ||||||

| MA4 | 0.70 | ||||||

| Behavioral intention (BI) | Hygiene | BI6 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.74 | |

| BI7 | 0.88 | ||||||

| BI8 | 0.85 | ||||||

| BI10 | 0.82 | ||||||

| Social restrictions | BI1 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.65 | ||

| BI2 | 0.82 | ||||||

| BI3 | 0.71 | ||||||

| BI5 | 0.85 | ||||||

| BI13 | 0.77 | ||||||

| Vaccination | BI11 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.57 | ||

| BI15 | 0.74 | ||||||

For the discriminant validity of each construct, HTMT analysis was conducted. As shown in Table 4, we found that the estimated ratio of HTMT for all variables is less than the provided criteria of 0.90.

Table 4.

HTMT analysis for discriminant validity

| Information overload (IO) | Message fatigue (MF) | Message avoidance (MA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MF | 0.28 | ||

| MA | 0.54 | 0.67 | |

| Behavioral intention | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.57 |

Common method bias

Common method bias (CMB) was examined because all the variables were from different sources using cross-sectional and self-reported measures and having multipoint Likert-type scales (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To determine the extent of CMB, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted based on the following criteria: the simultaneous loading of all the items in a principal component factor analysis should be below 50% of the total variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). We found that the total variance for a single factor of this study was 41.76%, suggesting that CMB did not affect the data.

Measurement model

Based on the findings of the reliability and validity tests of the latent variables, CFA was conducted to examine the measurement model with four interrelated latent variables (i.e., information overload, two-factor second-order COVID-19 message fatigue, message avoidance, and three-factor second-order behavioral intentions) and 26 observed variables. The results of CFA demonstrated that the measurement model had a good fit to the data: χ2(288) = 791.12, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.75, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR = 0.05. In addition, all factor loadings of the measured variables on the latent variables were significant (p < .001), and it was thus concluded that all the indicators represented and operationalized its latent factors well.

Structural model

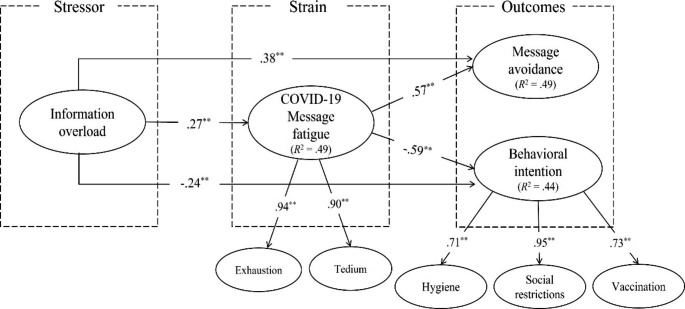

We implemented SEM to investigate the structural model and test the hypotheses including the mediating effects among variables of this study. With respect to the structural model, we first developed a model that included information overload as the predictor, second-order COVID-19 message fatigue as a mediator, and both message avoidance behavior and second-order behavioral intentions as the outcomes (see Fig. 2). The findings of SEM revealed that our hypothesized mediation model had an acceptable fit overall: χ2(289) = 797.00, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.76, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR = 0.05.

Fig. 2.

A mediational model of the relationships between perceived information overload, COVID-19 message fatigue, message avoidance, and behavioral intention. Note. Standardized coefficients are indicated. Solid lines represent significant paths; **p < .01

As illustrated in Fig. 2, perceived information overload was found to have a positive and significant association with COVID-19 message fatigue (b = 0.27, p < .01), supporting H1. COVID-19 message fatigue was positively associated with COVID-19 message avoidance behavior (b = 0.57, p < .01) whereas it was negatively and significantly linked with intentions to perform protective behaviors against COVID-19 (b = − 0.59, p < .01). Therefore, both H2 and H3 were supported.

To test the mediation effects of COVID-19 message fatigue, one between perceived information overload and message avoidance, and another between perceived information overload and behavioral intention, we added direct paths from perceived information overload to both message avoidance and behavioral intention. As indicated in Table 5, the indirect effect of perceived information overload on message avoidance through COVID-19 message fatigue (IO → MF → MA) was significant (b = 0.16, p < .01, 95% CI [0.09, 0.24]). Similarly, perceived information overload exerted a significant indirect effect on behavioral intention via COVID-19 message fatigue (IO → MF → BI; b = − 0.16, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.25, − 0.09]). These results supported H4a and H4b, demonstrating that COVID-19 message fatigue could partially mediate the relationships between perceived information overload and message avoidance, and between perceived information overload and behavioral intention.

Table 5.

The results of the mediation effect test

| Path | b | p | 95% CI | Mediation type observed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| IO → MF → MA | Indirect effect (a ⋅ b) | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.24 | Partial mediation |

| Direct effect (c’) | 0.38 | 0.001 | 0.26 | 0.48 | ||

| Total effect | 0.53 | 0.000 | 0.43 | 0.62 | ||

| IO → MF → BI | Indirect effect (a ⋅ b) | − 0.16 | 0.000 | − 0.25 | − 0.09 | Partial mediation |

| Direct effect (c’) | − 0.24 | 0.001 | − 0.37 | − 0.12 | ||

| Total effect | − 0.40 | 0.001 | − 0.52 | − 0.28 | ||

Note. IO: perceived information overload, MF: COVID-19 message fatigue, MA: message avoidance, BI: behavioral intention

Discussion

Considering that COVID-19 was a newly emerging and continuously evolving virus, a great amount of relevant information was disseminated to the public to inform threat of the virus and to reduce a person’s susceptibility to it. Many public health organizations used social media to communicate this health risk effectively as such platforms allow them to spread their information quickly and exponentially and gather feedback in real time. However, these positive roles of social media could be diminished and even reversed to the negative if individuals are exposed to excessive number of messages.

To understand how social media might challenge health risk communication, we investigated the dark side of social media usage in risk communication among US college students. More specifically, this study adopted the SSO framework to investigate how perceived information overload induces COVID-19 message fatigue and further how such fatigue affects message avoidance behavior and intentions to perform preventive behaviors against COVID-19. We also tested a mediational model that examined the direct and indirect effects of perceived information overload on message avoidance and behavioral intentions by considering COVID-19 message fatigue as a mediator.

Key findings

First, in line with previous studies that demonstrated the relationship between information overload and social media fatigue (e.g., Dhir et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2016a), our study confirmed the positive association between perceived information overload and the sense of fatigue toward COVID-19 messages. This represents that COVID-19 information overload can be a significant stressor, which causes COVID-19 message fatigue, the strain. This finding can be explained by cognitive overload as a part of cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988). According to this theory, our brains process information we receive every day from a variety of contexts (e.g., newspapers, radio, the Internet, interactions with others). However, when there is a massive amount and extremely repetitive information about a specific topic, we feel cognitive overload because our brains have limited cognitive capacities to absorb and handle them (Sweller, 1988). In the response to this overload, we feel psychological burdens, stress, and emotional exhaustion toward the information (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Hwang et al., 2020; Kominiarczuk & Ledzińska, 2014; Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008). As the COVID-19 pandemic got longer, social media users received a great deal of information, and they were constantly exposed to similar COVID-19-related messages. Such overexposure and too much repetition will cause cognitive overload in our brains, which would in turn bring psychological overwhelm and discomfort.

Additionally, we found that people were more likely to avoid another exposure to similar messages (e.g., social media posts) related to COVID-19 and less likely to perform recommended behaviors in the messages when they felt fatigued with the overexposure and extreme repetition of COVID-19 information on social media. These results were consistent with previous literature that fatigued individuals skip or avoid messages where relevant health issues are indicated (e.g., Kim & So, 2018; So et al., 2017) and show lower intentions to behave in the recommended way as the message suggests (e.g., Kim & So, 2018; Reynolds-Tylus et al., 2021). A possible explanation for this result is the relationship between emotions and behaviors that the cognitive-affective-conative model (Lavidge & Steiner, 1961) proposes. This theory argues that affective factors directly influence conational or behavioral outcomes. Specifically, when individuals get information, their negative emotions such as fatigue and frustration yield negative behavioral consequences such as information avoidance and discontinuance (Dai et al., 2020). Those who have feelings of fatigue toward COVID-19 messages may intentionally stay away from another exposure to similar types of messages on social media and be demotivated to follow the recommended protective behaviors because they do not want to experience such discomfort.

Finally, in accordance with our expectations, COVID-19 message fatigue partially mediated the association between perceived information overload and message avoidance as well as the association between perceived information overload and behavioral intention to follow protective behaviors against COVID-19. Those who were overloaded by information about COVID-19 on social media were more likely to feel fatigued toward COVID-19 messages, and then showed message avoidance behavior and lower levels of COVID-19 protective behavioral intention such as wearing a mask and controlling their social activities. In other words, perceived information overload exerted its direct and indirect effects through COVID-19 message fatigue on message avoidance and behavioral intention against COVID-19.

These significant findings can be explained by cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988) and psychological reactance theory (Brehm & Brehm,1981). The cognitive load theory argues that when people encounter massive tasks or information that exceed their capabilities to handle them, it reduces their effectiveness. That is, the cognitive surplus that requires excessive processing capabilities can trigger negative psychological responses toward a target. According to the psychological reactance theory, as a form of psychological response, reactance is aroused to regain lost freedom when it is threatened by some stimuli. That is, when individuals feel that their autonomy to act in their free will is threatened, they feel unpleasant and discomfort. Individuals respond to such threats with certain reverse behaviors such as reacting in the opposite way of what they are told.

When we are exposed to unwanted amount and type of messages that exceed our expectations (e.g., overexposure and too redundant messages), our freedom of information consumption (in terms of topic and amount) may be under threat. Once this freedom threat is generated, we may try to deal with this violation by showing reverse reactions such as showing fewer behavior changes or adopting opposite attitudes and/or behaviors to what those messages promote and persuade, thereby decreasing their persuasive effectiveness (Quick et al., 2013). In the context of COVID-19-related messages on social media, too much information about the virus leading to cognitive overload may hinder a fatigued user’s motivation to seek additional information about COVID-19 and to follow COVID-19 protective behaviors recommended by the relevant messages.

Theoretical implications

Our study includes several theoretical implications. First, this study theoretically elaborates on the roles of social media in the context of health risk communication, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic with a focus on COVID-19 message fatigue. Social media can be useful for health risk communication in conveying and sharing health-related information to a large number of users and increasing their risk perceptions (Heldman et al., 2013). However, as this study empirically demonstrated, too much information exposed through social media platforms triggers psychological fatigue, which in turn leads to ignoring relevant messages on social media and being demotivated to perform the recommended behaviors in those messages. That is, people may show such reactions (i.e., intentional ignorance of the COVID-19-related messages and lower behavioral intentions) as their defense strategies to alleviate negative and undesirable feelings (i.e., fatigue). Thus, these findings provide an understanding of the negative aspects of social media use in facilitating health risk communication on such outlets.

Additionally, as mentioned in the beginning, Koeske and Koeske (1993) initially developed the SSO framework to explore how stress leads to negative outcomes in work-specific environments. However, this model has not been tested in demonstrating social media-induced fatigue, especially regarding COVID-19-related messages. A mechanical-based theory, which focuses on the process from stimuli to behavior, has not been applied in the COVID-19 pandemic context such as employing the SSO framework to examine information overload and message fatigue on social media during the pandemic. In this regard, our study shows a mechanism of how our cognition, psychological status, and behaviors interplay. That is, our findings confirm the validity of the SSO framework by demonstrating that perceived information overload can trigger social media users’ conational factors (i.e., COVID-19 message avoidance and intention to adopt COVID-19 preventive behaviors) during the COVID-19 pandemic when they are exhausted by too much and too repetitive COVID-19-related messages on social media.

Our research demonstrates that our feelings of cognitive overload can influence behaviors when being exposed to information on social media. This implies that perception of information overload influences our psychological status and behavioral outcomes. Being exposed to too many similar messages on social media is a catalyst of psychologically exhaustive tasks which lead to fatigue and behaviors that are not consistent with the messages’ intentions. Overall, the results of this study help understand the mechanism of information overload in the age of digital media and information society. This study allows us to understand perceived information overload on social media not only explains why individuals get fatigued and exhausted from certain types of messages but also why they may show undesired behaviors.

Practical implications

This study also has several practical implications. First and foremost, our findings can be used to create an effective information dissemination strategy for government and public health organizations when they design health message campaigns via social media. Bearing in mind that overexposure to similar messages can create message fatigue, which in turn makes people avoid such messages and not adopt the recommended behaviors, health message designers may want to focus on creating diverse types of messages (e.g., textual, images, videos). They may also do better if focused on creating quality and impactful messages rather than spreading the same kind of messages over and over through social media. This way, social media users may still be intrigued to learn about various health risks delivered from diverse types of messages and not feel tired and unmotivated to try recommended behaviors in the messages.

In addition to the information strategy for public health campaigns, our findings may be useful to individual social media users in reflecting on their own experiences of social media uses especially those during the COVID-19 pandemic. They may be able to relate to our findings if they have felt fatigued about seeing and reading the same kinds of messages on social media repeatedly, and as a result, some may have actually avoided more exposure to similar kinds of messages and felt unmotivated to follow recommended behaviors against COVID-19. They may have wondered why they had such a reaction to those health-risk messages when in fact, those messages were trying to tell people what was safe and what could save their lives. Our findings provide an explanatory mechanism for such puzzling reactions and thus, more understanding of seemingly unreasonable public behaviors.

In general, these study findings can be used to suggest the public about moderate amount of social media usage as healthy behavior due to the potentially negative effects of overexposure on social media. Most likely, heavy users of social media would be exposed to more messages on social media; thus, if they do not want to feel fatigued about similar kinds of messages, the most effective and immediate solution would be to cut down the amount of exposure time. Although we cannot limit individual users’ free will and choice of how much time they spend on social media, research findings as these can at least inform them of the undesirable impact of information overload and overexposure to similar kinds of messages on social media.

Limitations and directions for future research

A few limitations of this study are worth mentioning for improvement in future research. The first limitation concerns the nature of the sample. We recruited participants (i.e., college students) from one university in one country during a specific time period (October - December 2020). This situation obstructs the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to collect data from different countries and various pandemic phases. Second and relatedly, the cross-sectional design of this study prevents us from making any definite claims of causality among the variables studied and an alternative ordering between them may occur in reality. In addition, this study used the self-reporting method which might include selection and response biases in reflecting participants’ actual thoughts and feelings. Further research should adopt longitudinal or multiple methods such as interviews and experiments to verify the causal relationships between variables.

Another potential direction for future research would be examining the content and valence of many COVID-19 messages. The reason for participants’ lowered motivation for engaging in protective behaviors during the pandemic could also be related to the nature of messages such as mis/disinformation related to the pandemic and negative comments from participants’ contacts on social media. Mis/disinformation about the risks of COVID-19 vaccines and the effectiveness of face masks and social distancing in stopping the spread of the virus could give people doubts especially when they are repeated many times and shared by close contacts (Lee et al., 2022). Thus, future studies can also adopt a content analysis to investigate the accuracy of COVID-19 information shared on social media and examine whether the accuracy of information plays a moderating role between perceived information overload and message avoidance and/or behavioral intention.

Conclusion

The primary purpose of repetitive messaging in risk communication is to increase awareness about potential or imminent danger, thereby enhancing risk perception and protecting public health and life. However, the feeling of message fatigue may lead us to be reluctant to accept similar types of messages despite their utility and necessity, and further decrease our intentions to adopt the protective behaviors alleviating the risk. The findings of this study showed that perception of COVID-19 information overload on social media significantly predicted the level of fatigue toward those messages. This feeling of message fatigue seemed to make people avoid another exposure to similar types of messages while diminishing their intentions to adopt protective behaviors against the COVID-19 pandemic. We also identified this message fatigue as a significant mediator between those two relationships. As COVID-19 spread accelerated, information on COVID-19 was constantly updated and sources of the information refreshed their messages on social media. As demonstrated in our study, relevant information sources such as WHO and CDC may need to consider receivers’ likelihood of feeling fatigued by their overly redundant messages and find a more effective messaging strategy balancing between repetitiveness and reactance.

Appendix

COVID-19 Message Fatigue (MF) scale.

| MF1 | I am burned out from hearing that unprotected COVID-19 is a serious problem. |

|---|---|

| MF2 | I am sick of hearing about consequences of unprotected COVID-19. |

| MF3 | I am tired of hearing about the importance of protecting ourselves from COVID-19. |

| MF4 | COVID-19-related messages make me want to sigh. |

| MF5 | Health messages about COVID-19 are boring. |

| MF6 | COVID-19-related messages make me want to yawn. |

| MF7 | I find messages about COVID-19 to be dull and monotonous. |

| MF8 | COVID-19-related messages are tedious. |

-

2.

Information Overload (IO) scale.

[In response to COVID-19 pandemic…]

| IO1 | I am often distracted by the excessive amount of information on social media. |

|---|---|

| IO2 | I am overwhelmed by the amount of information that I process on a daily basis from social media. |

| IO3 | I feel some problems with too much information in social media to synthesize instead of not having enough information |

-

3.

(modified) Message Avoidance (MA) scale.

| MA1 | I intentionally ignore some messages about COVID-19 on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, etc.). |

|---|---|

| MA2 | I intentionally don’t pay attention to some messages about COVID-19 on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, etc.). |

| MA3 | I scroll down Web pages to avoid some messages about COVID-19 on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, etc.). |

| MA4 | I use technical means to avoid some messages about COVID-19 on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, etc.). |

-

4.

Behavioral Intention (BI) scale.

| BI1 | I will likely keep limiting person-to-person interactions. |

|---|---|

| BI2 | I will likely avoid engaging in mass gatherings (10 or more people) in the near future. |

| BI3 | I will likely keep wearing a mask or cloth covering my mouth and nose in public areas. |

| BI4 | I intend to stay at home when I feel sick. |

| BI5 | I will likely always maintain at least 6-feet of physical distance (practice social distancing) |

| BI6 | I will likely wash my hands frequently with soap and water for at least 20 s after I have been in a public place. |

| BI7 | I intend to keep using a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. |

| BI8 | I intend to avoid touching my eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands. |

| BI9 | I will likely cover my mouth and nose when I cough or sneeze in public places. |

| BI10 | I will likely clean and disinfect frequently touched surfaces (e.g., tables, desks, handles, keyboards, cell phone and laptop screens, etc.) daily. |

| BI11 | I intend to get a flu vaccine to save healthcare resources for the care of patients with COVID-19 in the near future. |

| BI12 | I will likely monitor my health daily. |

| BI13 | I intend not to make unnecessary trips. |

| BI14 | When I have been in close contact with someone who has COVID-19, I intend to stay at home. |

| BI15 | I intend to get a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available in the near future. |

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Code and data availability

Data for this work are available at https://osf.io/d538b/?view_only=1bdef0f3fcd94edfa171527b3632b42a.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Juhyung Sun, Email: jsun@ou.edu.

Sun Kyong Lee, Email: sunnylee@korea.ac.kr.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atalan A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2020;56:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm, J. W., & Brehm, S. S. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. Academic Press.

- Bright LF, Kleiser SB, Grau SL. Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;44:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Masood A, Luqman A, Ali A. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and poor academic performance: Antecedents and consequences from stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Computers in Human Behavior. 2018;85:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research. 2020;287:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A. K., Nickson, C. P., Rudolph, J. W., Lee, A., & Joynt, G. M. (2020). Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: Early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia, 1–4. 10.1111/anae.15057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cho C. Why do people avoid advertising on the internet? Journal of Advertising. 2004;33(4):89–97. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2004.10639175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B, Ali A, Wang H. Exploring information avoidance intention of social media users: A cognition–affect–conation perspective. Internet Research. 2020;30(5):1455–1478. doi: 10.1108/INTR-06-2019-0225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel SJ. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects. 2020;49(1):91–96. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A, Yossatorn Y, Kaur P, Chen S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management. 2018;40:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A, Kaur P, Chen S, Pallesen S. Antecedents and consequences of social media fatigue. International Journal of Information Management. 2019;48:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eppler MJ, Mengis J. The concept of information overload: A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. The Information Society. 2004;20(5):325–344. doi: 10.1080/01972240490507974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Lacker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18:39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth V, Linnan HW, Potter P. Communicating the threat of emerging infections to the public. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2000;6(4):337–347. doi: 10.3201/eid0604.000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frew, P. M., Williams, V. A., Shapiro, E. T., Sanchez, T., Rosenberg, E. S., Fenimore, V. L., & Sullivan, P. S. (2013). From (un)willingness to involvement: Development of a successful study brand for recruitment of diverse MSM to a longitudinal HIV research. International Journal of Population Research, 1–9. 10.1155/2013/624245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Grabill JT, Simmons WM. Toward a critical rhetoric of risk communication: Producing citizens and the role of technical communicators. Technical Communication Quarterly. 1998;7(4):415–441. doi: 10.1080/10572259809364640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, M., Li, Y., Scoles, J. D., & Zhu, Y. (2022). COVID-19 message fatigue: How does it predict preventive behavioral intentions and what types of information are people tired of hearing about? Health Communication, 1–10. 10.1080/10410236.2021.2023385 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Guo Y, Lu Z, Kuang H, Wang C. Message avoidance behavior on social network sites: Information irrelevance, overload, and the moderating role of time pressure. International Journal of Information Management. 2020;52:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. 7. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Heath RL, O’Hair HD. Handbook of risk and crisis communication. London, United Kingdom: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Heldman AB, Schindelar J, Weaver JB. Social media engagement and public health communication: Implications for public health organizations being truly “social. Public Health Reviews. 2013;35(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03391698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hwang MY, Hong JC, Tai KH, Chen JT, Gouldthorp T. The relationship between the online social anxiety, perceived information overload and fatigue, and job engagement of civil servant LINE users. Government Information Quarterly. 2020;37(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2019.101423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam AN, Laato S, Talukder S, Sutinen E. Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2020;159:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karr-Wisniewski P, Lu Y. When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26(5):1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, So J. How message fatigue toward health messages leads to ineffective persuasive outcomes: Examining the mediating roles of reactance and inattention. Journal of Health Communication. 2018;23(1):109–116. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1414900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnick KN, Krugman DM, Cameron GT. Compassion fatigue: Communication and burnout toward social problems. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 1996;73:687–707. doi: 10.1177/107769909607300314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koeske GF, Koeske RD. A preliminary test of a stress-strain-outcome model for reconceptualizing the burnout phenomenon. Journal of Social Service Research. 1993;17(3–4):107–135. doi: 10.1300/J079v17n03_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kominiarczuk N, Ledzińska M. Turn down the noise: Information overload, conscientiousness and their connection to individual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;60:S76. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavidge RJ, Steiner GA. A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness. Journal of Marketing. 1961;25(6):59–62. doi: 10.1177/002224296102500611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AR, Son SM, Kim KK. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kim K, Koh J. Antecedents of news consumers’ perceived information overload and news consumption patterns in the USA. International Journal of Contents. 2016;12(3):1–11. doi: 10.5392/IJoC.2016.12.3.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lindsey N, Kim K. The effect of news consumption via social media and news information overload on the perceptions of journalistic norms and practices. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;75:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Sun J, Jang S, Connelly S. Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Scientific Reports. 2022;12:13681. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Liu W, Yoganathan V, Osburg VS. COVID-19 information overload and generation Z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technological Forecasting & Social Change. 2021;166:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luqman, A., Masood, A., Shahzad, F., Shahbaz, M., & Feng, Y. (2020). Untangling the adverse effects of late-night usage of smartphone-based SNS among University students. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1–17. 10.1080/0144929X.2020.1773538

- Malecki, K., Keating, J. A., & Safdar, N. (2020). Crisis communication and public perception of COVID-19 risk in the era of social media. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 1–6. 10.1093/cid/ciaa758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center (2019). Social media fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020;75(5):631–643. doi: 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick, B. L., Shen, L., & Dillard, J. P. (2013). Reactance theory and persuasion. In J. P. Dillard & L. Shen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of persuasion: Advances in theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 167–183). Sage

- Ragu-Nathan TS, Tarafdar M, Ragu-Nathan BS, Tu Q. The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Information Systems Research. 2008;19(4):417–433. doi: 10.1287/isre.1070.0165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Seeger MW. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication. 2005;10(1):43–55. doi: 10.1080/10810730590904571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds-Tylus, T., Lukacena, K. M., & Truban, O. (2021). Message fatigue to bystander intervention messages: Examining pathways of resistance among college men. Health Communication, 36(13), 1759–1767. 10.1080/10410236.2020.1794551 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T., Mayer, J., & Weaver, F. (2003, November). Prevention message fatigue as an influence on condom use among urban MSM. In 131st Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association

- Shi J, Smith SW. The effects of fear appeal message repetition on perceived threat, perceived efficacy, and behavioral intention in the extended parallel process model. Health Communication. 2016;31(3):275–286. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.948145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C, Yu L, Wang N, Cheng B, Cao X. Effects of social media overload on academic performance: A stressor–strain–outcome perspective. Asian Journal of Communication. 2020;30(2):179–197. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2020.1748073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin W, Lin TTC. Who avoids location-based advertising and why? Investigating the relationship between user perceptions and advertising avoidance. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;63:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- So J, Popova L. A profile of individuals with anti-tobacco message fatigue. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2018;42(1):109–118. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.42.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So J, Kim S, Cohen H. Message fatigue: Conceptual definition, operationalization, and correlates. Communication Monographs. 2017;84(1):5–29. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2016.1250429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweller J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science. 1988;12:257–285. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez D, Ten Thij M, Bathina K, Rutter LA, Bollen J. Social media insights into US mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal analysis of Twitter data. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(12):e21418. doi: 10.2196/21418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visschers VH, Meertens RM, Passchier WW, De Vries NN. Probability information in risk communication: A review of the research literature. Risk Analysis: An International Journal. 2009;29(2):267–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling C, Radisch J, Jacobzone S. The use of social media in risk and crisis communication. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance. 2013;24:1–42. doi: 10.1787/5k3v01fskp9s-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting A, Williams D. Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qualitative Market Research. 2013;16(4):362–369. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2013-0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2022a). Risk communication and community engagement (RCCE). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications

- World Health Organization (2022b). General information on risk communication. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/risk-communications/guidance

- Yu, L., Shi, C., & Cao, X. (2019, January). Understanding the effect of social media overload on academic performance: a stressor-strain-outcome perspective. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 2657–2666.

- Zhang S, Zhao L, Lu Y, Yang J. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behaviour in social network services. Information & Management. 2016;53(7):904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2016.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Ding, X., & Ma, L. (2020). The influences of information overload and social overload on intention to switch in social media. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1–14. 10.1080/0144929X.2020.1800820

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this work are available at https://osf.io/d538b/?view_only=1bdef0f3fcd94edfa171527b3632b42a.