Abstract

Background

Over half of patients with elevated blood pressure require multi-drug treatment to achieve blood pressure control. However, multi-drug treatment may lead to lower adherence and more adverse drug effects compared with monotherapy.

Objective

The Quadruple Ultra-low-dose Treatment for Hypertension (QUARTET) USA trial was designed to evaluate whether initiating treatment with ultra-low-dose quadruple-combination therapy will lower office blood pressure more effectively, and with fewer side effects, compared with initiating standard dose monotherapy in treatment naive patients with SBP < 180 and DBP < 110 mm Hg and patients on monotherapy with SBP < 160 and DBP < 100 mm Hg.

Methods/Design

QUARTET USA was a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03640312) conducted in federally qualified health centers in a large city in the US. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to either ultra-low-dose quadruple combination therapy or standard dose monotherapy. The primary outcome was mean change from baseline in office systolic blood pressure at 12-weeks, adjusted for baseline values. Secondary outcomes included measures of blood pressure change and variability, medication adherence, and health related quality of life. Safety outcomes included occurrence of serious adverse events, relevant adverse drug effects, and electrolyte abnormalities. A process evaluation aimed to understand provider experiences of implementation and participant experiences around side effects, adherence, and trust with clinical care.

Discussion

QUARTET USA was designed to evaluate whether a novel approach to blood pressure control would lower office blood pressure more effectively, and with fewer side effects, compared with standard dose monotherapy. QUARTET USA was conducted within a network of federally qualified healthcare centers with the aim of generating information on the safety and efficacy of ultra-low-dose quadruple-combination therapy in diverse groups that experience a high burden of hypertension.

Hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg based on the 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines, is a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality globally.1 In the United States, nearly half of adults have hypertension with sub-optimal control, particularly among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults in whom control rates are less than 25% and have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-4

The benefits of blood pressure lowering in reducing cardiovascular events are unequivocal. Blood pressure lowering by 10 mm Hg systolic reduces all-cause mortality by 11% (relative risk [RR] = 0.89 [95% CI 0.85, 0.95]), coronary heart disease by 16% (RR = 0.84 [95% CI 0.79, 0.90]), and stroke by 36% (RR = 0.64 [95% CI 0.56, 0.73]).5 Therefore, improving blood pressure control is a strategic priority for reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease in the United States and globally.6, 7

However, there are multiple barriers to hypertension control, including patient-and physician-related factors. For patients living in medically underserved and under-resourced communities, the compounding effects of multiple social and structural determinants of health such as food insecurity, unstable housing, community violence, lack of recreation, and overall social vulnerability increases risk of hypertension and related adverse outcomes.8 Chronic perceived stress and repeated exposures to stressful situations that are commonly associated with lower income areas also contribute to poorer health outcomes, including hypertension.9, 10 Finally, while affordability to medication has always been an issue for those with limited resources, in recent years, the emergence of pharmacy deserts – on top of the already existing “food deserts” and lack of access to services – has exacerbated this issue.11 This compounding of factors makes treating patients with chronic conditions, including hypertension, a challenge for clinicians working with underserved communities. Thus, these populations often experience the greatest disparities in hypertension control and resulting morbidity and mortality and are important to include in trials testing novel approaches to blood pressure control.

Current US guidelines typically recommend initiating monotherapy, up titrating or switching drugs if not tolerated, and adding other agents if needed in most patients who have stage 1 or stage 2 hypertension.12 This strategy often takes multiple visits to achieve blood pressure goals, which results in most patients remaining on monotherapy with inadequate blood pressure control. However, upfront low-dose combination therapy is more effective and efficient approach, including 2-, 3-, and even 4-drug combinations.13-15 For example, compared with placebo, a two-drug combination of quarter-dose therapy reduces systolic blood pressure by 10 mm Hg, and a 4-drug combination of quarter-dose therapy systolic blood pressure by 20 mm Hg. These changes contrast with only 5-6 mm Hg to 8-9 mm Hg lowering of systolic blood pressure with doubling from half dose to full dose therapy of a single drug, respectively.15, 16

In August 2021, the QUARTET trial in Australia reported a greater systolic blood pressure lowering effect with an ultra-low-dose, quadruple fixed-dose blood pressure lowering combination among 591 patients with SBP < 180 and DBP < 110 mm Hg.16, 17 Participants in the investigational product arm received a single-pill combination that included irbesartan 37.5 mg, amlodipine 1.25 mg, indapamide 0.625 mg, and bisoprolol 2.5 mg once daily as a “quadpill,” and those in the control arm received a matching comparator pill that included irbesartan 150 mg once daily. Step up therapy was allowed in either arm. At 12-week follow-up, 15% and 40% of intervention and control participants respectively were on additional blood pressure lowering medications. Compared with the control arm, participants randomized to initial quadpill had a mean 6.9 mm Hg (95% CI: 4.9 mm Hg-8.9 mm Hg) greater systolic blood pressure lowering at 12 weeks, which was sustained at 12 months. There were no serious adverse events due to syncope, falls, or acute kidney injury. The study participants largely self-identified as White (82%) and Asian (12%) race/ethnicity with 23% receiving additional government support for health care costs. Thus, there is promising evidence of an ultra-low-dose combination approach, but additional data are needed in more diverse populations and settings, especially among individuals from the low socioeconomic position who bear a disproportionate burden of hypertension and its complications.

Our aim was to investigate, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, whether initiating treatment with ultra-low-dose quadruple-combination therapy ("LDQT"), or 4 drugs in 1 pill, would lower office blood pressure more effectively, and with fewer side effects, compared with initiating standard dose monotherapy in treatment naive patients with SBP < 180 and DBP < 110 mm Hg and patients on monotherapy with SBP < 160 and DBP < 100 mm Hg in federally qualified health centers in a large city in the US.

Methods

The methods described are based on the Standardized Reporting Items: Recommendations for Intervention Trials (SPIRIT) statement and checklist.18

Study design

QUARTET USA was a 12-week double-blind type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation randomized controlled trial that sought to recruit 87 patients with high blood pressure (Figure 1). Eligible and enrolled participants were randomized 1:1 to either the interventional arm to receive a single-pill combination therapy of candesartan 2 mg, amlodipine 1.25 mg, indapamide 0.625 mg, and bisoprolol 2.5 mg, or to the control arm to receive a matched active comparator of candesartan 8 mg. The primary outcome was the mean change from baseline in automated office systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks after adjustment for baseline values. Secondary outcomes included other blood pressure measures at 6- and 12-weeks, proportion of patients with hypertension control (percent with systolic blood pressure < 130 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure < 80 mm Hg) at 6 and 12 weeks, medication adherence defined by pill counts, and mean change in health-related quality of life using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Systems Global Health instrument. Safety outcomes included the percentage of patients with serious adverse events, percentage of patients with adverse events of special interest, and percentage of patients with electrolyte abnormalities. A process evaluation was performed to understand provider experiences of implementation of a low-dose quadruple combination therapy and participant experiences around side effects, adherence, and trust with clinical care.

Figure 1.

QUARTET USA Study Schema.

Funding

The study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R33HL139852).

Participants

The study randomized the first participant on August 30, 2019, and enrollment closed on May 31, 2022. Upon closure of the study, 62 (71%) patients were randomized, and 56 (64%) completed study participation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Setting, locations, and recruitment

Trial participants were recruited from the Access Community Health Network (ACCESS) in the greater Chicagoland area in Illinois. Potentially eligible participants across the ACCESS network were identified through electronic health records in Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). The study staff screened identified patients through chart review in Epic and sent those that were potentially eligible to the patient’s primary health care provider. The primary health care provider at the participating center verified eligibility and then study staff contacted patients by phone. Healthcare providers at participating centers also directly referred potentially eligible participants to the study team. Potentially eligible patients were sent electronic messages through the ACCESS patient portal or were provided with information about the study in their After Visit Summary (AVS). Study staff then sought informed consent and screened interested participants at one of two ACCESS health centers (ACCESS Ashland Family Health Center or ACCESS Martin T. Russo Family Health Center). Randomization, 6-week, and 12-week study visits occurred at the enrolling site.

Intervention

Patients who were eligible to participate in the trial were randomized (1:1 allocation) to one of two study arms, and they took daily: (1) low-dose quadruple therapy (LDQT) comprising: candesartan 2 mg, amlodipine 1.25 mg, indapamide 0.625 mg, and bisoprolol 2.5 mg, or (2) matching comparator of candesartan 8 mg. The LDQT included quarter standard doses of four blood pressure lowering medications, each of which is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hypertension.19, 20 Standard dose for each drug followed methodologies from similar trials, and was defined as the most reported usual maintenance dose recorded by the British National Formulary or Martindale and the Monthly Index of Medical Specialties.19-21 The active comparator followed current clinical practice guidelines for most Americans, initiating treatment with an angiotensin II receptor blocker, which has the most favorable side effect profile of any blood pressure lowering therapy.19

In both arms, if blood pressure was not controlled (systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mm Hg) at the 6-week follow-up assessment, then study staff provided participants with an additional pill of amlodipine 5 mg to supplement their study drug, which may be of particularly effective among some race/ethnic groups, including African-Americans.12

All study drug used in the trial were prepared, packaged, and labelled by a third-party manufacturer according to Good Manufacturing Practice. The trial was conducted under an Investigational New Drug authorization under purview of the Food and Drug Administration. Each participant was assigned a medication kit which includes 2 bottles of study drug with 49 capsules (or 7 weeks’ supply) each. The capsules in the control and active comparator arm were identical in appearance. The unblinded study statistician pregenerated the study randomization sequences, stratified by site, using an independent R script (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing Platform) and uploaded into REDCap, and provided the manufacturer with the randomization sequences and corresponding randomly generated drug kit numbers to preserve the blinding.22 The manufacturer provided standard labeling for all drug kits such that the only link between the study arm assignment and the participant would be the participant’s study ID and their kit number. Participants who were using monotherapy at the time of enrollment were asked to stop their treatment while taking the study drug. Each participant was provided with 1 bottle at the time of randomization and was asked to return it at the 6-week visit when they were provided the second bottle. Participants were counseled by study staff to take their medication once daily at a consistent time, though a specific time of day was not promoted.

Study procedures

Based on medical record review and baseline assessments, study staff screened patients and randomized only after confirming eligibility (Table II). During the screening and randomization visit(s), the participant completed an informed consent form, provided demographics information, and had their blood pressure assessed by the research team. If the participant remained eligible, they provided a blood and urine sample, completed a 12- or one-lead electrocardiogram, and responded to the baseline study questionnaires. Once clinical and laboratory assessments confirmed eligibility, then the participant was randomized, and the study drug was dispensed (Table II).

Table II.

Study timeline and procedures.

| Study timeline | Screening and randomization |

6-Week follow-up visit |

12-week follow-up visit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit Window | −12 weeks | +/− 7 days | +/− 7 days |

| Location | Health center with telehealth screening and eConsent option | Health center | Health center |

| Study activities | |||

| Informed consent | X* | ||

| Demographics † | X* | ||

| Automated office (health center) blood pressure measured in the previous 12 weeks | X* | ||

| Blood pressure and heart rate measurements, by research team | X | X | X |

| Electrocardiogram | X ‡ | ||

| Anthropometrics and medical history | X* | ||

| Concomitant medications | X* | X | X |

| Lifestyle questions | X* | ||

| PROMIS global health | X* | X | |

| Laboratory assessments§ | X ‡ | X | X |

| 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitor | X | X | |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | X* | ||

| Randomization | X | ||

| Study drug dispensation | X | X | |

| Study drug return | X | X | |

| Medication adherence | X | X | |

| Participant status | X | X | X |

| Health service utilization | X | X | |

| Adverse events and serious adverse events | X | X | X |

This form may be completed electronically via a telehealth visit up to 90 days before the date of randomization (12 weeks in the case of previous automated office blood pressure measurement).

Such as date of birth, sex, and ethnicity.

If these tests completed within 3 months of the screening visit, and the results are available, then these tests will not be required at this visit.

Urine test and blood tests. Blood tests include sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, urea, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, AST, ALT, glucose, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. Urinary analysis include hCG (for women only) and urinary albumin and creatinine for both men and women. For women, urine test is required to rule out pregnancy.Abbreviations: PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system.

Blood pressure measurements used for screening, baseline, 6-week, and 12-week visits were performed using an Omron HEM 907 Automated Blood Pressure Monitor. For study participants who had their 6-week and 12-week visits conducted via telehealth due to the pandemic, Omron Series 5 and Series 3 blood pressure monitors were used. Research-grade blood pressure measurements were performed using a standard protocol, including measurement within a quiet room with the participant seated in a chair with both feet on the ground and placement of a well-fitting cuff. After a 5-minute, unobserved rest period, measurements of blood pressure were performed in triplicate at 1-minute intervals. The mean of the second and third measurements were used for analyses.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) was optional, and performed using a SunTech Oscar 2 ABPM device. The participant was fitted with the device during a clinical visit, and the device was programmed to record blood pressures at 30-minute intervals during day-time and 60-minute intervals throughout the night. The participant was asked to wear the device for 26 hours before returning it to the health center. While the participant was wearing the ABPM, they were asked to complete a diary documenting any circumstances surrounding blood pressure measurements such as elevated stress, movement, or discomfort that could influence the results.

Participants were asked to return to the health center within 6 weeks ± 7 days of randomization. During the 6-week visit, participants had their blood pressure and heart rate measured, their medication history verified, and their labs redrawn. The participants were interviewed to assess medication adherence, occurrence of any adverse events, and interim utilization of healthcare services. Participants returned their first bottle of medication and were provided with a refill, as well as add-on amlodipine (5 mg) if indicated based on 6-week blood pressure. Study staff performed a pill count of the returned medication to assess relative adherence to the study medication. After the 6-week visit, participants were asked to return to the health center within 6 weeks ± 7 days for their final assessment. The 12-week visit included the same procedures completed at the 6-week visit as well as completion of the health-related quality of life global health assessment using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), and optional follow up completion of a 24-hour ABPM assessment.23

Adverse events were probed during both the 6- and 12-week visits and focused on events of special interest (Supplement: Known Side Effects), which are known to be associated with the drug components in the interventional arm. A blinded, independent safety monitor reviewed all adverse events monthly and provided an assessment on severity and relatedness to the investigational product. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were immediately communicated to the study team through automated alerts within the electronic data capture system. These were reviewed by a study clinician for the likelihood of relatedness to the study medication and were reported through appropriate regulatory channels. All adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities by an independent reviewer from the lowest level term code to the system organ classes code.24

Participants were provided free transportation to the healthcare center for all visits, when needed.

Outcomes

Primary, secondary, and safety outcomes are listed in Table III.

Table III.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Primary outcome |

|---|

|

| Secondary outcomes |

|

| Safety outcomes |

|

Randomization

A randomization schedule for each site was prepared by the unblinded trial statistician and loaded into RED-Cap.25 Upon confirmation of eligibility by blinded study personnel, participants were randomized via the randomization module which returns a study drug kit number. These methods preserved blinding of treatment allocation, since only the unblinded trial statisticians had access to the master list of drug kit numbers and corresponding treatment codes. All other study personnel were blinded to the randomization sequence and treatment allocation.

Sample size

The initial sample size calculations called for a total of 365 participants to be randomized (1:1 allocation). We anticipated an analytic sample size of 292 based on 365 participants at randomization and a 20% dropout rate by the 12-week follow-up checkpoint. We originally based sample size and power calculations conservatively on an independent 2-sample t test. Based on results of interim analyses, we updated our recruitment target to 87 participants (1:1 allocation). The analytic sample size of 77 was anticipated based on 87 participants at randomization and a conservatively estimated 12% dropout rate by the 12-week follow-up checkpoint based on an 8% dropout rate observed through September 2021.

The initial, conservative plan for primary outcome analyses involving an independent 2-sample t test provided an estimated 80% power to detect a 5 mm Hg difference in SBP between the intervention and comparator arms assuming a 2-sided 5% level of significance and a 15 mm Hg standard deviation in outcome. These estimates were based on a 2017 Cochrane systematic review update evaluating the effects of fixed-dose combination therapy and systematic review on quarter dose combination therapy, and a pilot trial of quarter-dose combination therapy.26 We assumed baseline systolic blood pressure has a moderate correlation with follow-up SBP (r ≈ 0.5-0.6); under this assumption, initial sample size calculations based on analysis of covariance had the potential to allow for over 90% power under the same assumptions for remaining parameters.

At the request of the study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Board, we conducted an interim conditional power analysis, taking into consideration information from both the QUARTET USA trial data as of August 2021 and further the QUARTET (Australia) results.16 These interim analyses, incorporating information to date, suggested that an analytic sample size of at least 77 would provide over 90% conditional power. Assuming a 12% dropout rate target recruitment became 87 randomized participants to detect the same 5 mm Hg difference in SBP change.

Data collection and management

Data were collected on paper case report forms, which were maintained at the study site in a locked, secure location. Data from the paper case report forms were abstracted to electronic case report forms maintained using the Northwestern University REDCap instance. Data were reviewed monthly by the study team following centralized monitoring through Data Status and Quality Reports and REDCap reporting features. The contents of these Data Status and Quality Reports focused on essential study data including screening and consent, enrollment, demographics, medication adherence, protocol adherence, primary and secondary response variables, adverse events and serious adverse events, concomitant medications, and laboratory data. In addition to these aggregate data summarizations, statistical methods for monitoring clinical trial data were employed.27 The general strategies included:

Descriptive statistic summaries overall and by site for essential study data as indicated above.

Missing or out of range values.

Frequency of outlying values overall and by site.

- Process measures overall and by site:

- Screen failure rate

- Deviations and adverse events, including serious adverse events, by site

- Proportion of dropouts / losses to follow-up

Evaluating important response and safety data univariately and longitudinal trajectories over time (within the same person).

Medication adherence.

Statistical analyses

The primary study analysis is a linear mixed model with fixed study arm and baseline outcome value effects and a random participant effect to account for within-participant correlation. We plan to conduct both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Supplemental Table 1).

Secondary analyses and safety analyses will utilize data from all checkpoints via generalized linear mixed modeling methods appropriate to the specific outcome of interest. Adverse event rates will be tabulated overall and by arm, and chi-squared tests or exact methods will evaluate the differences across arms in event rates at the participant level.

Interim analysis

No interim outcome analyses were planned for this study. At the request of the study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Board, we conducted a conditional power analysis in August 2021, taking into consideration information from both the QUARTET USA trial data as of August 2021 and recommendations were made based on these analyses and information from the QUARTET (Australia) results.16

Protocol changes

QUARTET USA was launched 6 months before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study team continuously monitored, evaluated, and tailored the execution of the study under guidance and oversight of the external Data and Safety Monitoring Board to adapt to challenges inherent to the setting in which the trial was conducted, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical operations, and interactions between the two. Protocol modifications made throughout the course of the study are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Process evaluation

The simultaneous collection of efficacy and implementation or process outcomes, usually through quantitative and qualitative evaluation, is the hallmark of a type 1 hybrid trial design that aids in future implementation and scalability. Process evaluations complement the findings from randomized trials and can provide important information that cannot be elicited with quantitative outcomes alone. In the context of a randomized trial, process evaluations can be used to evaluate intervention acceptability, perceived benefits and concerns, and factors that influence implementation. In addition, process evaluations may provide an opportunity to formulate hypotheses leading to further analyses of the trial data.

We planned to enroll 10 health care providers and 30 QUARTET USA participants. Interviewers followed a semi-structured topic guide for both the healthcare providers and QUARTET USA participant interviews to ensure consistency in the topics explored during each interview. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and anonymized. At the end of each interview, the interviewer reflected on the content and noted the main themes arising and any relevant remarks about the context of the interview.

Healthcare provider interviews were performed in English and elicited providers’ views on how healthcare staff can influence patient decisions about treatment for hypertension, benefits and concerns related to LDQT vs standard therapy, and feasibility of implementing an LDQT strategy for hypertension treatment in routine clinical practice. Participant interviews were performed in English or Spanish, after the participant completed their final study visit. Participants and study staff remained blinded to the study drug the participant received. Participant interview topics included:

Their views on the benefits, disadvantages, and acceptability of their current treatment (LDQT or standard monotherapy).

Reports on specific instances where changes occurred to their usual adherence behavior and the circumstances surrounding these changes.

Factors that hinder or facilitate their attitude towards adherence to therapy within the trial.

Factors that would be most likely to make participants’ adherence behavior outside the trial situation differ from that exhibited in the trial.

Probing questions were developed and refined to explore responses to these broad topics.

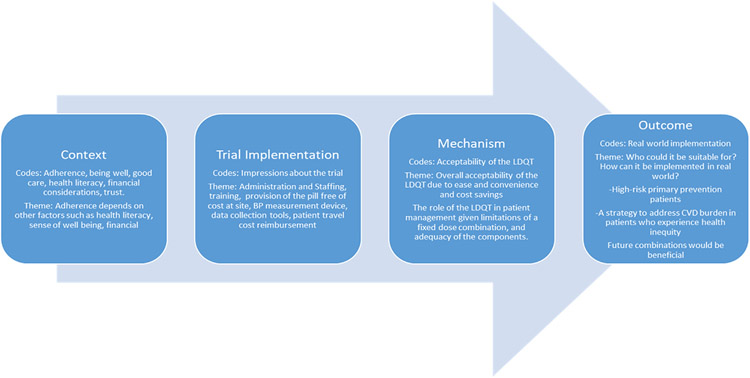

Interviews will be professionally transcribed and coded by at least 2 researchers using Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA). We will use the constant comparative method to code the transcripts independently and develop an initial coding framework encompassing both patients’ and providers’ perspectives, allowing triangulation of findings within each code.28 The coding framework will be refined with input from the study investigators and interview team. The Realist framework of context–mechanism–outcomes will be utilized to develop the themes (Figure 2).29, 30

Figure 2.

Codes and themes within the realist framework (context-mechanism-outcome). CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

Monitoring

Trial monitoring was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice by a third party. Site qualification and initiation visits were completed prior to enrollment of the first participant. A single interim site monitoring visit at each health center was completed to review site compliance. Assessments included 100% of informed consent forms and eligibility, and a random sample of all other forms. Site records and conduct are reviewed with accordance to standards for Food and Drug Administration-regulated interventional trials. Study recruitment, enrollment, and safety data were reported to and reviewed by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board every six months.

Dissemination and data sharing

Data generated through this trial will be shared through National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Biologic Specimen and Data Repository (NHBLI BioLINCC) along with necessary elements for general use including codebook, protocol, case report forms, statistical analysis plan, and reports of primary and secondary outcomes. Data will also be shared with investigators of the QUARTET (Australia) trial for a planned pooled analysis.

Ethics

Informed consent was provided by each participant. Ethical oversight was provided by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. The trial was prospectively registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov under NCT03640312 and the study record was updated in accordance with approved changes to the study protocol.

Discussion

The QUARTET USA trial was designed to evaluate whether a novel approach to blood pressure control will lower office blood pressure more effectively, and with fewer adverse effects, compared with initiation of standard dose monotherapy for treatment naive patients with SBP < 180 and DBP < 110 mm Hg and patients on monotherapy with SBP < 160 and DBP < 100 mm Hg. The QUARTET USA trial was conducted within a network of federally qualified healthcare centers in Chicago, Illinois with the aim of generating evidence on the safety and efficacy of ultra-low-dose quadruple-combination therapy in a diverse patient population that experiences significant hypertension related health disparities and barriers to research participation. These data will be used with results from the QUARTET (Australia) trial in a pooled analysis to increase generalizability of the results and inform future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the patients and teams at Access Community Health Network. We would like to thank members of the QUARTET USA study team who have contributed to the success of the trial, including Ms. Mianzhao (Tracy) Guo, Ms. Alexandra Soriano, Mx. Rolando Serna, Ms. Patricia Helbin, Mr. Edgar Pizarro, Dr. Daneen Woodard, Dr. Natasha Pavlovcik, Dr. Charity Alikpala, Ms. Katherine McKeough, Ms. Sonya Hopkins, and Ms. Eloisa Lopez. We would like to thank members of the QUARTET Australia study team who have contributed to the success of the trial, including Dr. Emily Atkins and Dr. Anthony Rodgers. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R33HL139852). The funders were not involved in the development of the study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication. The program officer representing the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute participated in Data and Safety Monitoring Board activities.

QUARTET USA Operations Committee

Dr. Mark Huffman, Dr. Jody Ciolino, Ms. Abigail Baldridge, Dr. Sadiya Khan, Dr. Stephen Persell, Dr. James Paparello, Dr. Namratha Kandula, Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, Ms. Ashima Chopra, Dr. Olutobi Sanuade, Dr. Jairo Mejia, Ms. Danielle Lazar, Ms. Linda Rosul, Ms. Hiba Abbas, Ms. Fallon Flowers, Ms. Adriana Quintana.

QUARTET USA Data and Safety Monitoring Board members

Dr. Paul Muntner (chair), Dr. Christopher Lindsell, Dr. Kenneth Jamer son, Dr. Emily Ander son, Ms. Perla Herrera.

Footnotes

Disclosures

MDH has pending patents for heart failure polypills. The George Institute for Global Health’s wholly owned enterprise, George Health Enterprises, has received investment funds to develop fixed-dose combination products containing aspirin, statin and blood pressure lowering drugs. Dr. Persell receives unrelated research support from Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd. Dr. Lloyd-Jones is an unpaid fiduciary officer of the American Heart Association.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2022.09.004.

References

- 1.Collaboration NCDRF. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021;398:957–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential U.S. Population Impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hypertension Cascade: Hypertension Prevalence, Treatment and Control Estimates Among US. Adults aged 18 years and older applying the criteria from the American college of cardiology and american heart association’s 2017 hypertension guideline — NHANES 2015–2018. 2021. Accessed 3 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estimated Hypertension Prevalence. Treatment, and Control Among U.S. Adults Tables, Million Hearts; 2018. Accessed 2 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karmali KN, Lloyd-Jones DM, Berendsen MA, et al. Drugs for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an overview of systematic reviews. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:341–9. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Control Hypertension. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/docs/SG-CTA-HTN-Control-Report-508.pdf [accessed 3 March 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guideline for the pharmacological treatment of hypertension in adults. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/344424/9789240033986-eng.pdf [accessed 3 March 2022]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King JB, Pinheiro LC, Bryan Ringel J, et al. Multiple social vulnerabilities to health disparities and hypertension and death in the REGARDS study. Hypertension 2022;79:196–206. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prather AA. Stress is a key to understanding many social determinants of health. Health Aff Blog 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200220.839562/. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: risks and implications for care. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009;6:712–22. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olumhense E, Husain N. Pharmacy deserts’ a growing health concern in Chicago, experts, residents say. Chicago Tribune; 2022. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-met-pharmacy-deserts-chicago-20180108-story.html. Accessed 28 March. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2199–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salam A, Atkins ER, Hsu B, et al. Efficacy and safety of triple versus dual combination blood pressure-lowering drug therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2019;37:1567–73. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salam A, Huffman MD, Kanukula R, et al. Two-drug fixed-dose combinations of blood pressure-lowering drugs as WHO essential medicines: An overview of efficacy, safety, and cost. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:1769–79. doi: 10.1111/jch.14009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow CK, Thakkar J, Bennett A, et al. Quarter-dose quadruple combination therapy for initial treatment of hypertension: placebo-controlled, crossover, randomised trial and systematic review. Lancet 2017;389:1035–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30260-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow CK, Atkins ER, Hillis GS, et al. Initial treatment with a single pill containing quadruple combination of quarter doses of blood pressure medicines versus standard dose monotherapy in patients with hypertension (QUARTET): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled trial. Lancet 2021;398(10305):1043–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01922-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow CK, Atkins ER, Billot L, et al. Ultra-low-dose quadruple combination blood pressure-lowering therapy in patients with hypertension: the QUARTET randomized controlled trial protocol. Am Heart J 2021;231:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, Jordan RE. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ 2003;326:1427. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett A, Chow CK, Chou M, et al. Efficacy and safety of quarter-dose blood pressure-lowering agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension 2017;70:85–93. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webster R, Salam A, de Silva HA, et al. Fixed low-dose triple combination antihypertensive medication vs usual care for blood pressure control in patients with mild to moderate hypertension in sri lanka: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;320:566–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. https://www.R-project.org/ Accessed 3 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009;18:873–80. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. International council for harmonisation of technical requirements for pharmaceuticals for human use. https://www.ich.org/page/meddra Accessed 8 March, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahiru E, de Cates AN, Farr MR, et al. Fixed-dose combination therapy for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009868.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkwood AA, Cox T, Hackshaw A. Application of methods for central statistical monitoring in clinical trials. Clin Trials 2013;10:783–806. doi: 10.1177/1740774513494504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 2009;119:1442–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonell C, Fletcher A, Morton M, et al. Realist randomised controlled trials: a new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:2299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.