Abstract

Purpose

Many countries prohibit payment for gamete donation, which means fertility clinics do not have to compensate donors. However, acquiring and utilizing donor sperm can still be expensive for fertility clinics. This study evaluates international fertility workers’ views on charging patients for altruistically donated sperm.

Methods

Using social media and email, we disseminated a SurveyMonkey survey with a question that was specifically focused on opinions about charging patients for altruistically donated sperm. Clinicians were able to select multiple pre-populated answer choices as well as write answers that reflected their views as an open-ended response. Snowball sampling was utilized to reach international fertility clinicians.

Results

Of 112 respondents from 14 countries, 88% believe it is acceptable to charge for altruistically donated sperm based on one or more of four different assenting categories: so patients appreciate that sperm is valuable, because it generates funds for the running of the clinic, to cover specific costs associated with sperm, and to make a profit for the clinic.

Conclusions

The consensus that charging for altruistically donated sperm is acceptable was not surprising since recruiting and processing donor sperm can be expensive for clinics. However, there were geographical differences for specific assenting answer choices which may be based on countries’ income, and healthcare system, as well as religious and cultural beliefs.

Keywords: Sperm donation, Profit, Altruism, International, Clinician perspectives

Introduction

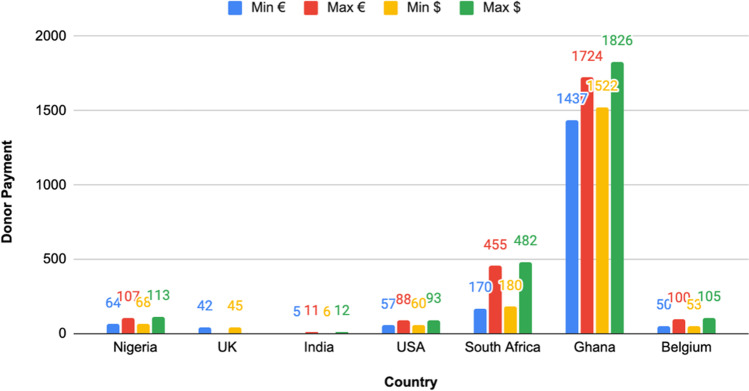

Social norms and legal regulation regarding compensation for sperm donation vary across countries. Some countries, such as New Zealand and Canada, completely prohibit compensation and anything else that can be seen as commercializing gametes [1, 2]. At the other end of the spectrum, countries like the USA allow sperm to be treated as unregulated market commodities. There are countries that take a middle ground, allowing for recompense for financial losses (e.g., transportation) and for nonfinancial losses (e.g., donor time and inconvenience) [3]. This is typically referred to as “altruistic donation” since clinics are not paying for the “commodity” of sperm but rather are renumerating individuals for their “service,” akin to compensation for jury duty in the USA and Canada [4]. The rates of compensation for altruistic and commercial donation vary by country (Fig. 1 [5–9]).

Fig. 1.

Range of compensation converted to euros and USD for sperm donors in countries that participated in the survey

Average payment for sperm donors in countries that participated in the survey

Acquiring donor sperm can also be expensive for fertility clinics, as they incur costs during every step from donor recruitment, sample quarantine, and donor rescreening to processing the semen and eventually inseminating a patient [10]. Only 5% of men who wish to donate sperm are cleared by clinics to become donors [10, 11]. Clinics typically take 8 weeks to 6 months to screen (and rescreen) donors, a process that typically includes health questionnaires including sexual and detailed multi-generation family history, blood typing, genetic testing, screening for infectious diseases, semen analysis, and test freeze-thaw, as well as considerations of donor motivation and implications counseling. These processes take both time and money [10, 11]. Once a donor is approved, costs for a clinic to acquire and store the sperm in the USA is around $675 (594 euros) which includes $350 (~308 euros) for lab processing including analysis of fertility status of the sperm and $325 (286 euros) for STI testing [12].

Nonetheless, sperm banking is big business. The global sperm bank market was valued at approximately USD 4.33 billion in 2019 and is expected to reach around USD 5.45 billion by 2026, expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 3.3% [13]. Sperm banks (or clinics) in Europe usually charge patients between 380 and 1060 euros per straw depending on the donor’s country of origin and anonymity requirements (open donations usually cost more) [14], while patients in the USA pay between $940 and $1020 per vial [12]. Patients also pay treatment costs: around $440 (416 euros) for natural cycle intrauterine Insemination (IUI) or around $630 (595) euros for stimulated IUI [15]. Thus, acquiring and utilizing a single straw of donated sperm can cost European patients between 796 and 1655 euros and Americans $1380 and $1650 [12–14].

Given the different practices regarding sperm donor compensation around the world, we were interested in asking fertility clinic workers what they think about charging for altruistically donated sperm. To our knowledge, there is limited discussion in the academic literature on this topic. Since specialists working in fertility clinics are the ones faced with this dilemma, we decided to solicit their views for this project. We were particularly interested in how views on this issue may vary internationally.

Methods

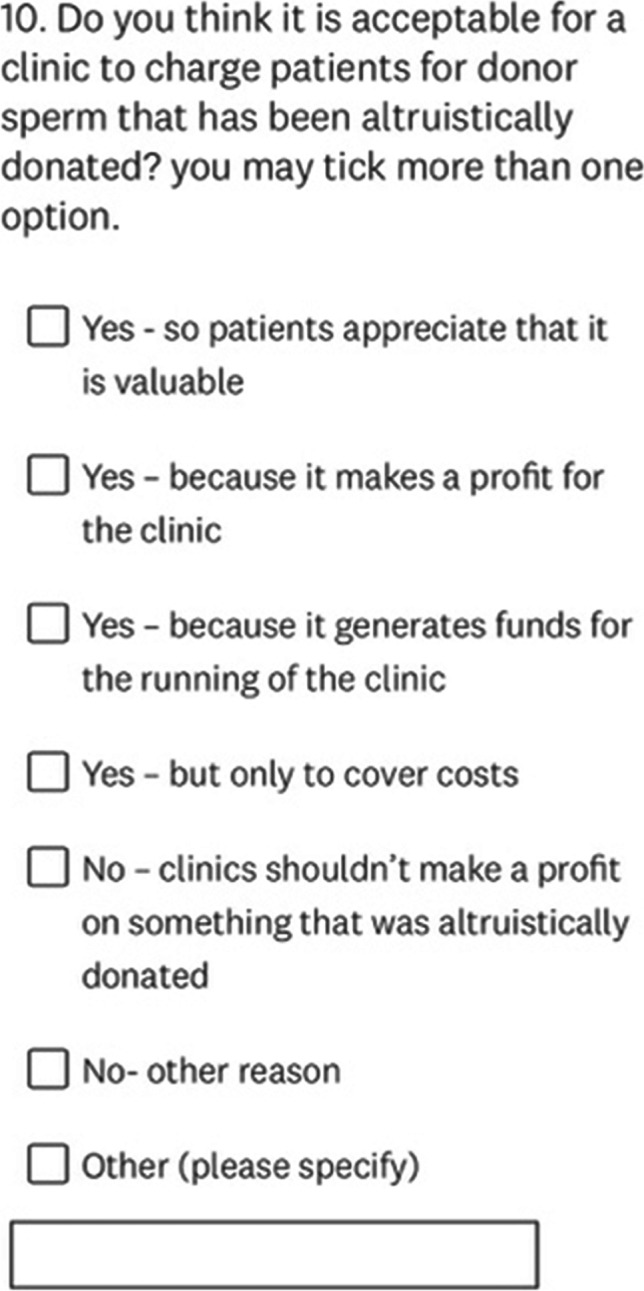

This project is part of a larger parent study [16] in which we examined the views of fertility specialist working in Assisted Reproductive Technology clinics on evaluation and treatment for male infertility. Our methods consisted of distributing, via personal social media accounts (Twitter and Facebook) and email (to known fertility clinician colleagues working in the UK, USA, and Nigeria), a SurveyMonkey (an online survey design software) survey. In addition, snowball sampling was utilized, since respondents were encouraged to share the survey to reach more international fertility clinicians. No paid advertisements were utilized, and respondents were not compensated. To our knowledge, all survey respondents are fertility clinicians; however, the survey was fully anonymized other than asking the location they work. No demographic information such as gender, age, race, length of time working in the industry, or specific occupation title or workplace (sperm bank, IVF clinic, etc.) was collected. This pilot study data is derived from a single question (Fig. 2) on a multiple-question survey based on responses to the question, “Do you think it is acceptable for a clinic to charge patients for donor sperm that has been altruistically donated?” Respondents were able to select more than one pre-populated answer choice, including four assenting and two dissenting. The assenting answer choices are yes because “it allows patients to appreciate that sperm is valuable,” “it generates funds for running the fertility clinics,” “to cover costs associated with utilizing the sperm,” and “to make a profit for the clinic.” The dissenting choices are “no, clinics shouldn’t make a profit on something that was altruistically donated,” or “no, other reason.” Respondents could also write-in any answer that reflected their views in the “other (please specify)” free-response section. The data from the pre-populated answer choices were compared based on overall number of assenting vs dissenting responses, specific reasoning for assenting responses, and geographic location. The free-text answers were used to provide explanations to pre-populated responses as well as guide literature searches to develop hypothesis for explaining survey results.

Fig. 2.

Screen capture of exact SurveyMonkey question distributed to participants. Participants were able to select more than one answer choice as well as type responses in the “other” free text box

Results

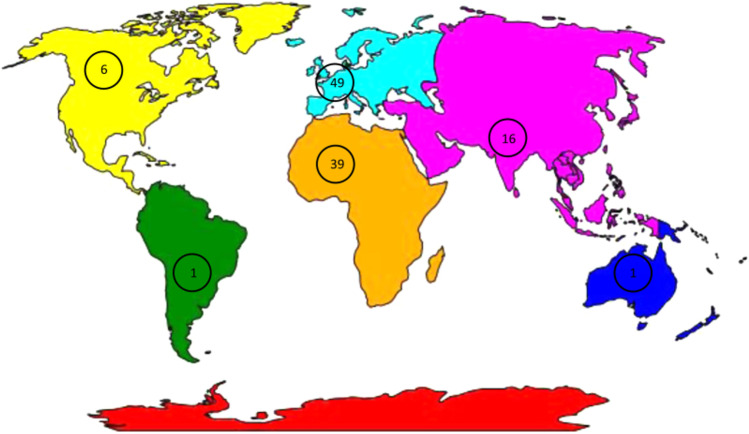

Our survey received 112 individual participants (P) from 14 countries including the following: the UK (P=45, 40.2%); Nigeria (P=37, 33%); India (P=12, 10.7%); the USA (P=6, 5.4%); Turkey and Belgium (each P=2, 1.8% respectively); Argentina, Australia, Ghana, Malaysia, Nepal, South Africa, Spain, Netherlands (each P=1, 0.9% respectively) (Fig. 3). Forty-six of these international survey respondents selected two or more of the multiple answer choices available. Since participants (P) were able to select multiple answer choice responses (N) there were 182 total responses with 160 supporting an assenting answer (N=160) and 22 dissenting choices (N=22).

Fig. 3.

The distribution of participants (P) based on continent of origin of 112 fertility clinicians who responded to the question should fertility clinics charge patients for altruistically donated sperm. Europe (blue, P= 49), Africa (orange, P= 39), South Asia (pink, P= 16), North America (yellow, P= 6), South America (green, P= 1), and Australia (dark blue, P= 1). Clinicians from 14 countries responded, with Nigeria and the UK accounting for the majority at 40.2% and 33.0% respectively

Fertility clinician respondents to survey regarding charging for altruistically donated sperm based on country

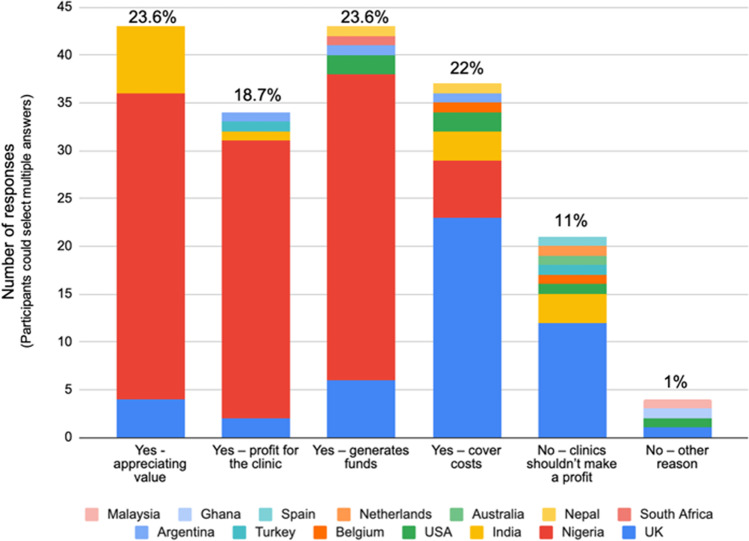

Eighty-eight percent (N=160) of responses supported charging for altruistically donated sperm based on one or more of the following four assenting reasons: 23.6% (N=43) believe it allows patients to appreciate that sperm is valuable, 23.6% (N=43) because it generated funds for running the fertility clinics, 22% (N=40) to cover costs associated with utilizing the sperm, and 18.7% (N=34) to make a profit for the clinic. Eleven percent (N=20) of responses opposed charging for altruistically donated sperm to make a profit. An additional 1% (N=2) of the responses were no for other reasons but did not specify (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The number of responses (N) based on participant’s country of origin to each of the categories ask in the survey including: yes—so patients appreciate sperm value (N=43, 23.6%); yes—because clinics can profit (N=34, 18.7%); yes—because it generated funds to run the clinic (N=43, 23.6%); yes—only to cover costs associated with sperm (N=40, 22%); no—clinics should not profit (N=20, 11%); and no—other (N=2, 1%). Eighty-eight percent (N=160) of the overall responses (N=182) cited a “Yes” answer supporting charging for altruistically donated sperm

International fertility workers response to the survey asking is it acceptable for a clinic to charge patients for donor sperm that has been altruistically donated

Slightly under a quarter of participant responses (23.6% (N=43)) support charging patients so they appreciate the value of the sperm. Notably, participants from just three countries—Nigeria, India, and the UK—were in support of this category. Similarly, almost a quarter (23.6% (N=43)) of the responses, from six countries, are in support of charging for sperm in order to generate funds for running the clinic. Nigeria accounted for 74.4% of the responses in this category. Nigerians also accounted for most of the responses coming from 5 countries (18.7% (N=34)) who support charging to generate a profit. In the free text section, Nigerians focused on a lack of national protocols allowing them to make profits (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey responses by country and with free text

| Yes - charging for altruistically donated sperm is acceptable - so patients appreciate that it is valuable | |

| Country | Free response |

| Nigeria |

“It is not appreciated if done for free” “If given freely, it will not be valued, so they have to pay for it” “It’s for the good of the patient so he/she can value the process and for the running of the centre” “Why not, it’s the right thing to do, it should not be given free to clients, they will not value it” |

| Yes - charging for altruistically donated sperm is acceptable – because it makes a profit for the clinic | |

| Country | Free response |

| Nigeria |

“This is how we make money as there are no set rules or protocol to follow unlike other countries” “We do not have a protocol, so we run it as it (suits) us” “It’s only normal for clients to pay for their services and this is one of it” |

| UK | “Yes, because meeting the right quality standards and taking responsibility for outcomes is a costly and risky enterprise. A profit motive can drive quality and investment.” |

| Yes - charging for altruistically donated sperm is acceptable – because it generates funds for running of the clinic | |

| Country | Free response |

| Nigeria |

“It could never be completely free as it takes significant costs to process, test, store, etc.” “Money will be made for the running of the affairs of the clinic” “Used for funding of the fertility centres (equipment and payments of staff)” “The government doesn’t sponsor this process, so we have to fund it ourselves so it’s a good way to keep it rolling” “Needed to fund the fertility hospital to keep it running” “Money needs to be made for the running of the fertility centre that that is one of the ways it can be made, we do not have sponsorship like other developed countries” |

| Yes - charging for altruistically donated sperm is acceptable – but only to cover costs | |

| Country | Free response |

| UK |

“It could never be completely free as it takes significant costs to process, test, store, etc.” “The costs of donor recruitment, screening, and quarantine storage need to be covered and this is not covered by the NHS in the area I work in” |

| Nigeria | “It’s normal to take money because we pay for the gametes as well so it is vice versa” |

| USA | “Even if the sperm has been donated there are still costs related to genetic testing of the viability of the sperm, storage, thawing and eventual use” |

Ten countries, the greatest number in any category (22% (N= 40)), support charging for sperm but only to cover costs associated with utilizing it. In contrast to the other answer choices where Nigerian respondents dominated, the UK comprised 57.5% of this category. In addition, participants from three different countries supported their reasoning in the free text section, giving this category the greatest response diversity (Table 1).

The minority of people (12% (N=20)) oppose making a profit from altruistic donations (Fig. 3). This dissenting response came from seven countries, with the UK in the majority ((60% (N=16)) (Table 1). In addition, 1% of total respondents also answered no but for other reasons. No respondent who selected a response in either no category left their reasoning in the free response section. Zero Nigerian respondents supported this category which is notable given that the UK and Nigeria contributed to most of the data with 40.2% and 33.0% of the total responses respectively (Fig. 3).

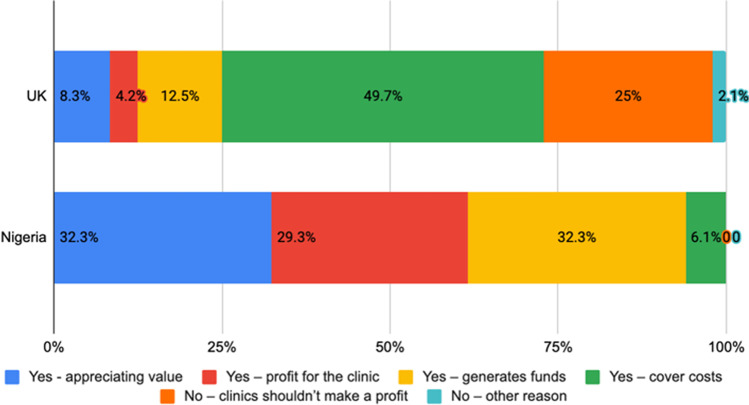

Nigeria and UK accounted for 73.2% of the total data, with their responses for each category differing considerably. 32.3% of participant responses from Nigeria agree with charging for donated sperm so patients appreciate its value while only 8.3% from the UK agree (Fig. 5). Similarly, 29.3% of Nigerian responses support charging to generate a profit and 32.3% to generate funds for running the clinic compared to 4.2% and 12.5% respectively from the UK. On the flip side, 49.7% of UK responses support charging to cover costs while only 6.1% of Nigerians agree. In addition, 27% of the UK responses opposed charging for altruistically donated sperm, while no one from Nigeria did.

Fig. 5.

The percentage of responses (N) by category for total number of Nigerian and UK survey participant responses respectively. Forty-five (P) UK clinicians participated and left 48 (N) responses with N=4 (8.3%) for yes, to appreciate value, N=2 (4.2%) for yes to generate profit, N=6 (12.5%) for yes to generate funds, N=23 (49.7%) yes to cover costs, N=12 (25%) for no, clinic’s shouldn’t make a profit, and N=1 (2.1%) for no, other reason. Thirty-seven (P) Nigerian clinicians participated and left 99 (N) responses with N=32 (32.3%) for yes, to appreciate value, N=29 (29.3%) for yes to generate profit, N=32 (32.3%) for yes to generate funds, and N=6 (6.1%) for yes to cover costs

Response from UK and Nigerian fertility workers to the survey asking if it is acceptable to charge for altruistically donated sperm

See Fig. 5.

Discussion and conclusion

To our knowledge, our study is one of the first to examine the views of professionals working in fertility clinics about charging patients for altruistically donated sperm. Based on overall responses to the assenting answer choices, almost 90% of the survey respondents supported charging self-funded patients for altruistically donated sperm. Generating funds for running the clinic, however, had the most diverse array of international support which may be explained by the cost of processing the sperm donations. As previously highlighted, STI and genetic testing as well as cryostorage and downstream lab processing of a sample can cost close to 600 euros, which the clinic will need to recoup from patients. Passing these costs on to patients may be the only realistic option that allows the clinic to run and provide treatment services. However, many were opposed to clinics making a profit from altruistic sperm donations, perhaps due to concerns that financial gains diminish human dignity by turning gametes into a commodity rather than supporting a donor’s desire to help others by providing the “gift of life” [17, 18]. By simply charging patients for the costs involved rather than adding a profit margin to the cost of sperm could seem more ethical to fertility clinicians while still being a sound business move. The implications here are that since reproductive medicine is a big business, it is a normal part of the process for clinics to charge for sperm regardless of whether it is altruistically donated or not. We are not here to make normative claims regarding if charging for altruistically donated sperm is right or wrong, but to point out that this is the descriptive practice that occurs.

Fewer UK respondents supported charging to generate a profit compared to those that agreed with generating funds, which may be explained by the UK’s broad-based and well-funded universal healthcare system [19]. Given that infertility care is frequently covered by the government, though coverage may vary across the UK [20], there may be less financial need to generate a profit than in countries with less consistent government assistance. In contrast, many non-western countries supported charging for sperm to generate a profit, which may be due to the lack of public funding for healthcare. According to the World Health Organization, the Nigerian government does not put the recommended amount of money into funding a healthcare system so it relies on 70% out of pocket payments for routine care [21]. India’s public healthcare system is also underfunded leading to 65% of basic healthcare costs being out of pocket for patients [22]. Because the healthcare systems are underfunded, fertility clinics must charge patients for all aspects of acquiring and utilizing donor sperm for artificial donor insemination. In addition to this, since the government does not regulate fertility clinics, they must act as a business and have profit margins in order to pay employees.

On top of healthcare system structure, there were also geographical differences based on culture and religion for supporting charging for altruistic sperm donation. For example, fertility clinicians in Nigeria place importance on patients appreciating the value of donated sperm, which may be due to the cultural significance placed on having children. In western Africa, which includes Nigeria, the family size preference is 6 children which is driven by the idea that parenthood brings identity and continuity [23, 24]. Specific reasons Nigerians in particular want children are for happiness and companionship, to maintain the family lineage, to assist in providing for the families’ economic security, and for gaining respect among their community [25]. The overwhelming desire to have children may explain why some Nigerians suffering with infertility are willing to spend between 55 and 100% of their yearly income on fertility treatments [26]. While people in the global North also venerate parenthood and are willing to spend significant sums of money to achieve it, one’s social worth is not dependent upon parenthood to the same degree [27]. In some places in the global South, there is the belief that a person who “has no children has no value in this world” [26]. This is particularly the case for women (regardless of which partner is physiologically infertility [24, 28, 29]), who may be the subject of local gossip, suffer verbal abuse at the hands of her husband and his extended family, or divorced and kicked out of the home without any financial or social security [30–32]. In contrast, many women in the global North who choose to delay having children in order to focus on careers are viewed by their communities as being voluntarily childless, and are encouraged to seek out fertility care should the need arise [27]. In short, the significant social stigma of infertility in Nigeria may contribute to the perception that sperm are valuable and consequently cost money.

Similarly, the stigmatization of infertility, coupled with religious beliefs, may explain why many participants from India also reported that sperm are valuable. In many Indian communities, social pressure, especially from the man’s family, is placed on the couple if they fail to conceive within 1 year of marriage, leading to subsequent loss of status [33]. Religious beliefs may provide an additional explanation to support patients finding value in donated sperm. Hinduism, which accounts for 79.8% of India’s population, condones use of donor sperm within a marriage (with the stipulation the sperm comes from a relative) [34, 35]. This supportive position stands in stark contrast to other religions, such as Catholicism and Islam, which traditionally oppose the use of donated gametes [35].

One limitation of this pilot study is that administering the survey by email and over social media could have caused sample bias, inadvertently excluding those without social media accounts. Other limitations include small sample size and that most respondents were from Nigeria and the UK since two of the authors have origins in these countries. In addition, clinicians working in the fertility industry, who therefore derive their livelihood from fertility care, may be extrinsically motivated to support charging for sperm compared to the general population.

Future research surveys obtaining more responses from other countries could clarify how cultural norms, religious beliefs, and healthcare systems affect responses by providing specific answer choices that encompass these suggested explanations. In addition, fertility clinicians should also be asked if they would support charging for sperm to fund compensation for donors if it is permitted in their country. Other directions for future research involve asking about the ethics of charging for altruistically donated oocytes since some clinicians believe financial compensation for oocyte donors is more important than sperm donors since the process is more invasive, risky, and time-consuming [36]. Additional future research could solicit opinions from fertility clinics business managers, as they are likely more familiar with the financial side of running a clinic.

As demand for sperm donation grows while supply decreases [37], we should continue to assess the role compensation plays for various stakeholders. Since many countries only allow altruistic donation, it is important to examine how fertility clinics will remain financially solvent given the various expenses associated with sperm donation and enhanced genetic screening. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of how the tension between the beliefs that sperm is invaluable and that sperm should not be commodified plays out in the context of altruistic sperm donation could be illuminating.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Manuscript has been read and approved by all authors. The manuscript has not been published and is not under review elsewhere.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yee S. ‘Gift without a price tag’: altruism in anonymous semen donation. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(1):3–13. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henein M, Ells C. Towards a Patient-centred regulation of gamete donation in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(9):1338–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuffield Council on Bioethics . Human bodies: donation for medicine and research. London: Nuffield Council on Bioethics; 2011. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid L, Ram N, Brown RB. Compensation for gamete donation: the analogy with jury duty. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2007;16(1):35–43. doi: 10.1017/S0963180107070041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commission, E. Commission Staff Working Document on the implementation of the principle of voluntary and unpaid donation for human tissues and cells Accompanying the document report from the commission to the european parliament, the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of the regions on the implementation of Directives 2004/23/EC, 2006/17/EC and 2006/86/EC setting standards of quality and safety for human tissues and cells. Brussels. 2016.

- 6.Cohen G, et al. Sperm donor anonymity and compensation: an experiment with American sperm donors. J Law Biosci. 2016;3(3):468–488. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsw052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eshemokha Udomoh. Cost of sperm donation in Nigeria + Requirements for sperm donation in Nigeria. Nigerian Health Blog; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhayana Neha. Students become sperm donors. New Delhi India: HT Digital Streams Ltd.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aevitas Fertility Clinic Sperm Bank . Become a sperm donor. South Africa: Aevitas Fertility Clinic; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidhu RS, et al. Reasons for rejecting potential donors from a sperm bank program. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1997;14(6):354–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02765841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almeling R. Gender and the value of bodily goods: commodification in egg and sperm donation. Law Contemp Probl. 2009;72(3):37–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Sperm Bank of California . How Much Does it Cost? Berkely, CA, USA: Reproductive Technologies INC.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dataintelo, Global Sperm bank market by service types (sperm storage, semen analysis, and genetic consultation), donor types (known donor and anonymous donor), end-uses (donor insemination and in vitro fertilization), and regions (Asia Pacific, Europe, North America, Middle East & Africa, and Latin America) – global industry analysis, growth, share, size, trends, and forecast from 2022 to 2030, in sperm bank market size, share, growth report 2020-2026. 2019: Dataintelo.com. p. 115.

- 14.European Sperm Bank . Prices of donor sperm. Denmark: European Sperm Bank ApS; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moolenaar LM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of assisted conception for male sub fertility. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30(6):659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olisa NP, Campo-Engelstein L, Martins da Silva S. Male infertility: what on earth is going on? Pilot international questionnaire study regarding clinical evaluation and fertility treatment for men. Reprod Fertil. 2022;3(3):207–215. doi: 10.1530/RAF-22-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong D, et al. An overview on ethical issues about sperm donation. Asian J Androl. 2009;11(6):645–652. doi: 10.1038/aja.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tober DM. Semen as gift, semen as goods: reproductive workers and the market in altruism. Body Soc. 2001;7(2-3):137–160. doi: 10.1177/1357034X0100700205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roe AM, Liberman A. A comparative analysis of the United kingdom and the United States health care systems. Health Care Manag. 2007;26(3):190–212. doi: 10.1097/01.HCM.0000285010.03526.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority. UK statistics for IVF and DI treatment, storage, and donation. Fertility Treatment. 2019; trends and figures. 2021. [cited 2022 5 May]

- 21.Okafor C. Improving outcomes in the Nigeria healthcare sector through public-private partnership. Afr Res Rev. 2016;10(4):1–17. doi: 10.4314/afrrev.v10i4.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . National health accounts estimates for India financial year 2015-16. India: National Health Care Systems Resource Centre; 2018. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amoo EO, et al. Fertility, Family size preference and contraceptive use in Sub-Saharan Africa: 1990-2014. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018;22(4):44–53. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2018/v22i4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoefman K, et al. The impact of functional and social value on the price of goods. PloS One. 2018;13(11):e0207075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Balen F, Trimbos-Kemper TCM. Involuntarily childless couples: their desire to have children and their motives. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;16(3):137–144. doi: 10.3109/01674829509024462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieuwenhuis SL, et al. The impact of infertility on infertile men and women in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria: a qualitative study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2009;13(3):85–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greil A, McQuillan J, Slauson-Blevins K. The social construction of infertility. Sociol Compass. 2011;5(8):736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00397.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ugwu EO, Onwuka CI, Okezie OA. Pattern and outcome of infertility in Enugu: the need to improve diagnostic facilities and approaches to management. Niger J Med. 2012;21(2):180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugwu EO, et al. Acceptability of artificial donor insemination among infertile couples in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:201–205. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S56324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui W. Mother or nothing: the agony of infertility. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):881–882. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.011210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimka RA, Dein SL. The work of a woman is to give birth to children: cultural constructions of infertility in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;17(2):102–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friday EO, et al. The social meaning of infertility in Southwest Nigeria. Health transition review : the cultural, social, and behavioural determinants of health. 1997;7(2):205–220. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts L, et al. Women and Infertility in a pronatalist culture: mental health in the slums of Mumbai. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:993–1003. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S273149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Central Intelligence Agency. Field listing - religions. The World Factbook. [cited 2021 September 22]

- 35.Sallam HN, Sallam NH. Religious aspects of assisted reproduction. Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn. 2016;8(1):33–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezeome I. Attitude of Nigerian obstetrician-gynecologists toward gamete donation. Niger J Clin Pract. 2021;24(6):896. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_270_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goedeke S, Shepherd D, Rodino IS. Support for recognition and payment options for egg and sperm donation in New Zealand and Australia. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(1):117–129. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]