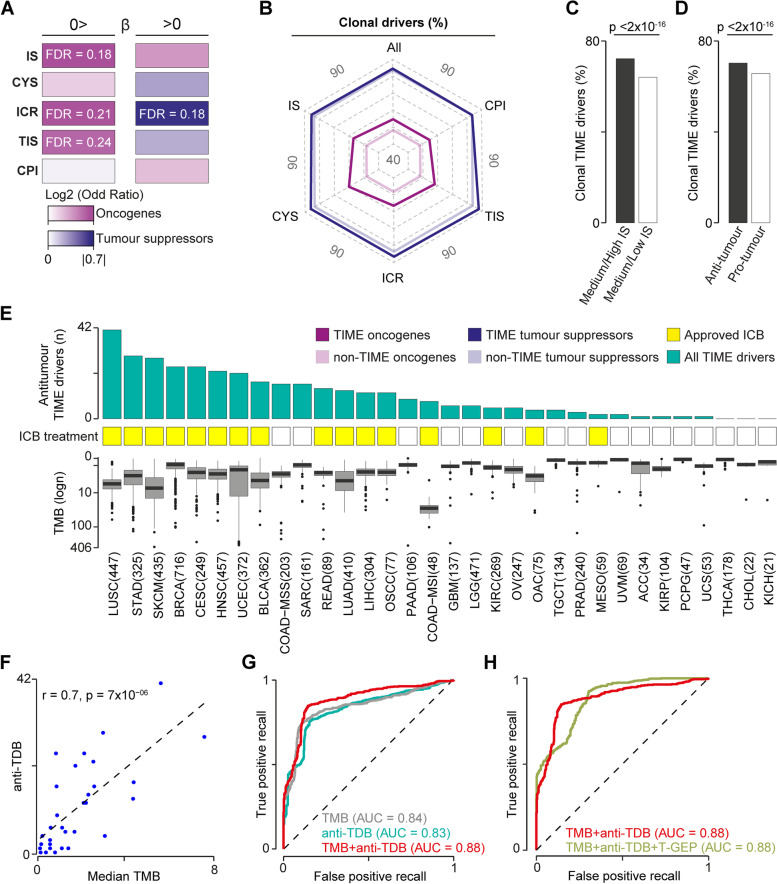

Fig. 2.

Effects of tumour suppressors and oncogenes on TIME and ICB response. A Enrichment of TIME drivers predictive of medium/low ( or medium/high ( TIME levels in tumours suppressors and oncogenes. B Proportions of TIME and non-TIME tumour suppressors or oncogenes with clonal damaging alterations. C Proportions of clonal TIME drivers predictive of high or low immune infiltration. D Proportions of clonal TIME drivers predictive of an anti-tumour (CYS, TIS, ICR , or CPI < 0) and pro-tumour (CYS, TIS, ICR , or CPI > 0) TIME. E Number of antitumour TIME drivers, approval ICB treatment and TMB across cancer types. The number of samples for each cancer type is shown brackets. F Pearson’s correlation between the median TMB and the number of antitumour TIME drivers in 31 cancer types, excluding COAD-MSI. ROC curves comparing the performance of TMB and anti-TDB (G) and T-cell-inflamed GEP (H) in predicting response to ICB. Recall rates and AUCs were calculated across 100 cross-validations. AUC, area under the curve; CPI, cancer-promoting inflammation; CYS, cytotoxicity score; ICB, immune checkpoint blockade; ICR, immunologic constant of rejection; IS, immune score; anti-TDB, antitumour TIME driver burden; GEP, gene expression profile; TIME, tumour immune microenvironment; TIS, tumour inflammation signature; TMB, tumour mutational burden; TOB, TIME oncogene burden; TTB, TIME tumour suppressor burden. TCGA abbreviations are listed in Additional File 2: Table S1. Proportions (A–D) were compared using Fisher’s exact test. In A, Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple testing was applied