Abstract

The alkynylation of 4-siloxyquinolinium triflates has been achieved under the influence of copper bis(oxazoline) catalysis. The identification of the optimal bis(oxazoline) ligand was informed through a computational approach that enabled the dihydroquinoline products to be produced with up to 96% enantiomeric excess. The conversions of the dihydroquinoline products to biologically relevant and diverse targets are reported.

Keywords: enantioselective catalysis, computational studies, alkynylations, heterocyclic cations, complex alkaloid synthesis

Quinolone and its derivatives are regarded as important biologically relevant heterocycles. These motifs can be found in numerous alkaloid-based active pharmaceutical ingredients and secondary metabolites. Some prominent examples include martinellic acid, a bradykinin receptor antagonist, the antibiotic helquinoline, and other valuable products including levonantradol, L-689,560, and the Hancock alkaloids (Figure 1).1−5

Figure 1.

Prominent examples of quinoline-based bioactive compounds.

Tetrahydroquinoline-based bioactive targets can make for challenging synthetic landscapes, especially if possessing multiple stereogenic centers like many of the compounds depicted in Figure 1. We were motivated by the challenge of generating quinolone-derived compounds with substituents at the 2-position, which is stereogenic (highlighted in purple in Figure 1). This motif is frequently observed in both small-molecule drug candidates and naturally occurring molecules. Tactical approaches toward the generation and absolute control of this 2-stereocenter include both intramolecular and intermolecular approaches. From an intramolecular standpoint, aza-Michael reactions of unprotected amines to provide dihydroquinolones in an enantioselective manner have been reported with several different organic catalysts, including phosphoric acid derivatives and thioureas.6 Intermolecular strategies typically center on conjugate addition reactions of organometallic reagents, such as Grignard reagents and organozinc reagents, to 4-quinolones.7,8 While high enantiocontrol can be achieved in these cases, these methods generally suffer from the use of sensitive reagents as well as expensive or non-commercially available ligands. With such limits of available methodologies, we hypothesized that an alkynylation reaction of 4-siloxyquinolinium triflates, reactive species generated in situ from quinolones, could give rise to a straightforward, robust, and highly enantioselective synthesis of desirable dihydroquinolones. Herein are the details of a computationally guided program that enabled the discovery of a hardy copper (bis)oxazoline catalyst system for the construction of a broad range of biologically attractive dihydroquinolines, along with exquisite enantiocontrol (up to 96% ee).

The in situ generation of heterocyclic cations can be a secret weapon in the creation of challenging stereocenters (Scheme 1). Akiba and co-workers are pioneers in demonstrating that the treatment of chromones with silyl triflates generates 4-siloxybenzopyrylium triflates.9 Ion pairs A and B (Scheme 1) are eager electrophiles that readily participate in desirable carbon–carbon bond forming events. Inspired by the attractive reactivity patterns of A, our group established protocols for the enantioselective alkylation and alkynylation of 4-siloxybenzopyrylium triflates.10 More importantly, the compatibility of A with both organic catalysis and organometallic catalysis opens up a range of possibilities in the context of influencing bond-forming events and stereocontrol.

Scheme 1. Heterocyclic Cations Can Operate as Key Intermediates in the Synthesis of Biologically Attractive Targets.

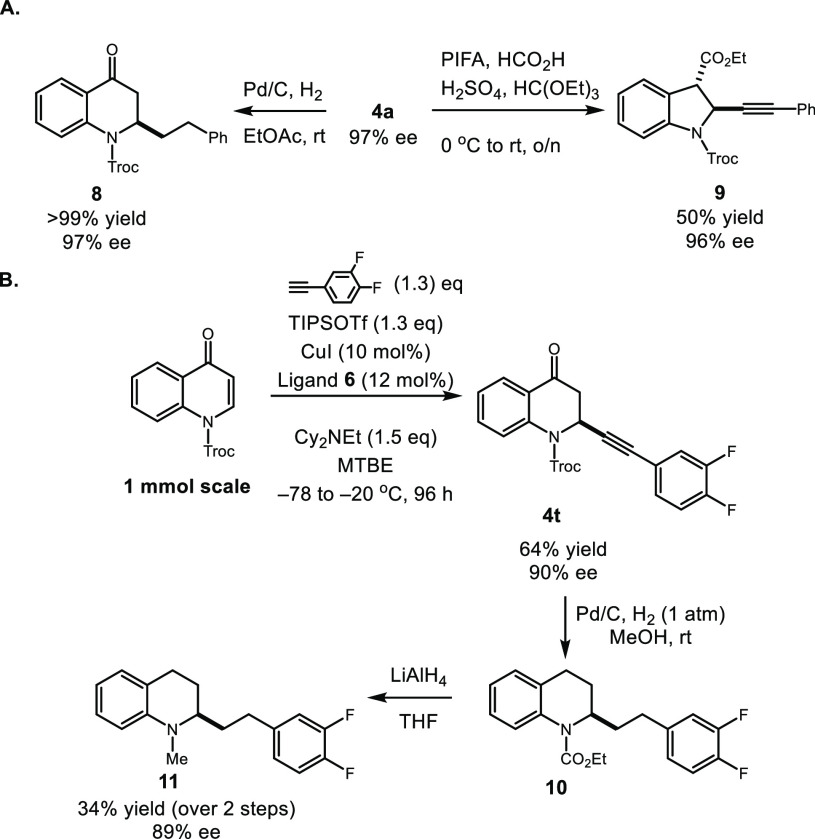

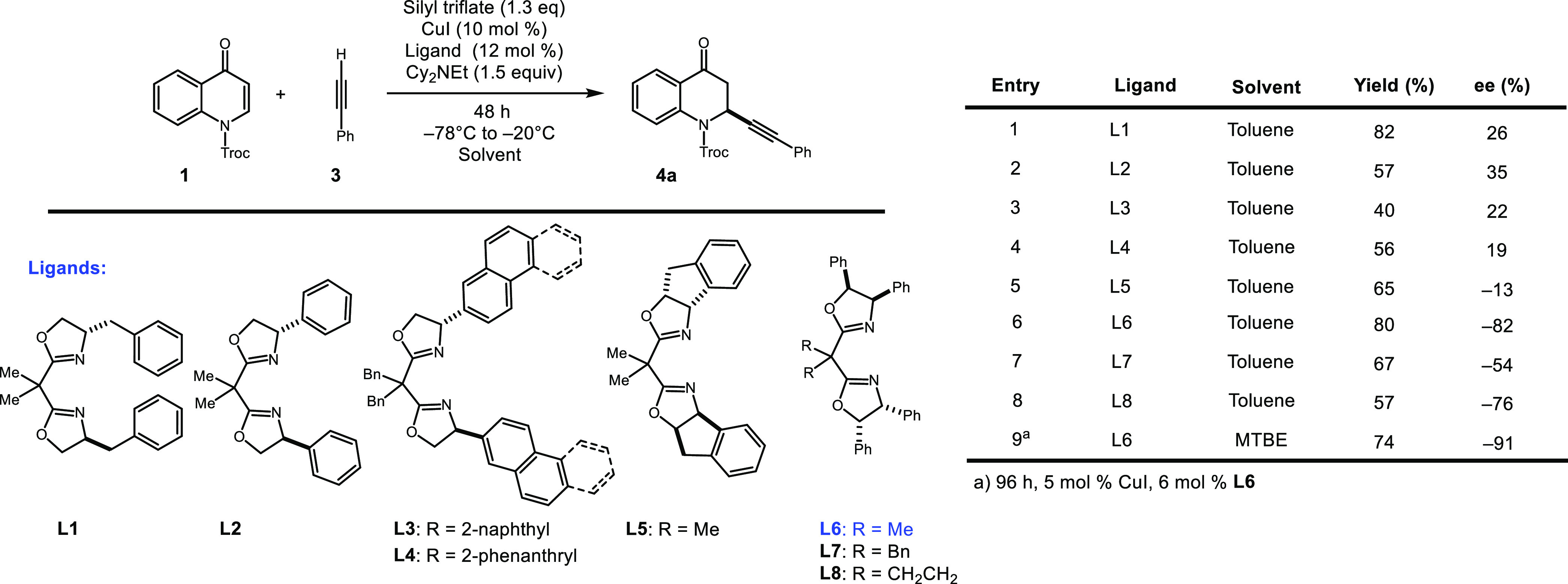

Our discovery of highly enantioselective alkynylations of benzopyrylium triflates in the presence of a copper bis(oxazoline) catalyst prompted our initiation of investigations into the facially selective alkynylation of quinolinium triflates. During our preparation of this article, Harutyunyan published a separate account on the addition of copper acetylides to quinolones, although there were only 3 enantioselective examples with modest stereocontrol (i.e., 54–86% ee).11 Building from our previous studies, our initial efforts employed benzyl bis(oxazoline) ligand-1 (L1) in the reaction between 2,2,2-trichloroethoxycarbonyl (Troc)-protected quinolone 1 and phenyl acetylene 3 (Table 1). An initial success of just 9% enantiomeric excess was achieved with trimethylsilyltriflate (TMSOTf), but it was evident that substantial ligand optimization was required (entry 1, Table 1). A slight increase in yield and enantiomeric excess was attained when switching to more bulky silyl triflates (tert-butyl dimethyl and triisopropylsilyl, entries 2 and 3). With triisopropryl silyl triflate (TIPSOTf) identified as the optimal Lewis acid, base screening next revealed that Cy2NEt dramatically increased the yield and slightly improved the selectivity (entry 5).

Table 1. Optimization of Alkynylation of Quinolinium Triflates.

| entry | silyl triflate | base | yield (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TMSOTf | iPr2NEt | 30 | 9 |

| 2 | TBSOTf | iPr2NEt | 15 | 13 |

| 3 | TIPSOTf | iPr2NEt | 40 | 22 |

| 4 | TIPSOTf | NEt3 | 19 | 24 |

| 5 | TIPSOTf | Cy2NEt | 82 | 26 |

In silico studies were performed on the reaction between the quinolinium triflate generated from 1 and phenyl acetylene 3 with the benzyl bis(oxazoline) ligand L1 with the intention of identifying interactions controlling the facial selectivity of the enantiodetermining step. The plan was to use this information to aid in the selection of ligands to increase enantioselectivity. Scheme 2 depicts the R and S transition states calculated with the density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d) (SDD for Cu) level of theory12 with their respective non-covalent interaction (NCI) plots.13 The transition state (A) leading to the observed major R-4a enantiomer (vide infra) plausibly benefits from favorable π-interactions between one of the benzyl arms, copper acetylide, and the main aromatic ring of the quinolinium ion. Moreover, a distance of 2.95 Å between the Troc group’s carbonyl oxygen and one methyl group’s hydrogen off of the backbone of the ligand was observed, potentially further stabilizing the transition state through electrostatic forces. The existence of these NCIs in the R transition (A) state versus the S transition state (B) was confirmed using NCIPLOT analysis (Scheme 2, green regions = attractive NCIs).

Scheme 2. Transition States of Enantio-Determining Steps for 1 with Ligand-1 as Determined at the B3LYP/SDD/6-31+G(d) Level of Theory.

Enthused by the theoretical observation of NCIs driving the enantiocontrol in the reaction, we hypothesized that additional aromatic characters on the ligand backbone may lead to an increase in facial selectivity. A library of ligands with varying and enhanced aromatic characters were next put to the test. We first found that when phenyl box ligand L2 was applied, the selectivity of the reaction increased to 35% ee (Scheme 3, entry 2). Moving along in our study, we were surprised to find that L3 and L4, containing 2-naphthyl and 2-phenanthryl substituents, were giving rise to lower enantiomeric excess of 22 and 19% ee, respectively. Similarly, indanyl-derived ligand L5 gave rise to just 13% ee (Scheme 3, entry 5). We were delighted to find that tetraphenyl box ligand L6 performed better than benzyl ligand L1 and phenyl ligand L2, furnishing product 4a with 80% yield and 82% ee. Upon switching the solvent to methyl tert-butyl ether and reducing catalyst and ligand loading to 5 and 6 mol %, respectively, the selectivity was improved to 91% ee (Scheme 3, entry 9).

Scheme 3. Effect of Ligand Scaffold on Enantiomeric Excess.

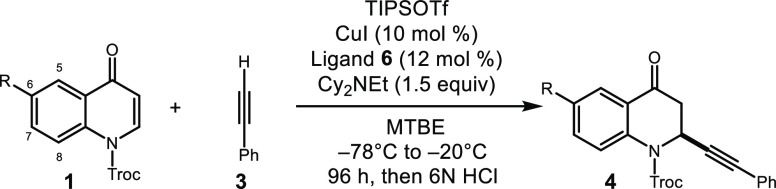

With the most optimal enantioselective conditions and protecting group identified (see Supporting Information), the focus was shifted to the substrate scope (Table 2). We first examined the scope with respect to the Troc-protected quinolone substrates and found that both electron-withdrawing and -donating groups were well tolerated in the 6-position and afforded the corresponding quinolone products (4b–4f) effectively. In nearly all cases, the optimized alkynylation conditions gave products in moderate to excellent (40–80%) yields and exceptional enantioselectivity (88–93%). Some structurally similar substrates (4b and 4c) provided the same selectivity yet drastically different reactivity patterns. In the case of 4b, low solubility of the starting material was observed, likely contributing to its poor chemical conversion. It should be noted that in all cases, unreacted starting material and deprotected quinolone could be recovered from the reaction mixture.

Table 2. Quinolone Substrate Scope.

Our attention was next turned toward exploring the scope of the terminal alkynes on quinolone 1 (Table 3). Aryl acetylenes bearing various substitutions gave rise to the desirable alknylated products with moderate to excellent levels of enantiocontrol. For example, para-substituted phenyl acetylenes performed well, including, chloro, bromo, nitro, and trifluoromethyl, thereby furnishing products (4i–4l) in 88–93% ee. para-Methoxy and methylated alkyne reaction partners also afforded products 4h and 4g, albeit with moderate selectivity (81 and 77% ee). The other desired alknylated products, such as 4p (96% ee) and the cuspareine precursor, 4t, were also prepared in high yields and enantioselectivity (90% ee). Heteroaryl groups, such as thiophene 4q, could be incorporated and provided the corresponding product at 47% yield and 88% ee. Moreover, alkenyl acetylenes also gave the desired products 4r and 4s with high enantioselectivity (80 and 87% ee, respectively).

Table 3. Alkyne Substrate Scope.

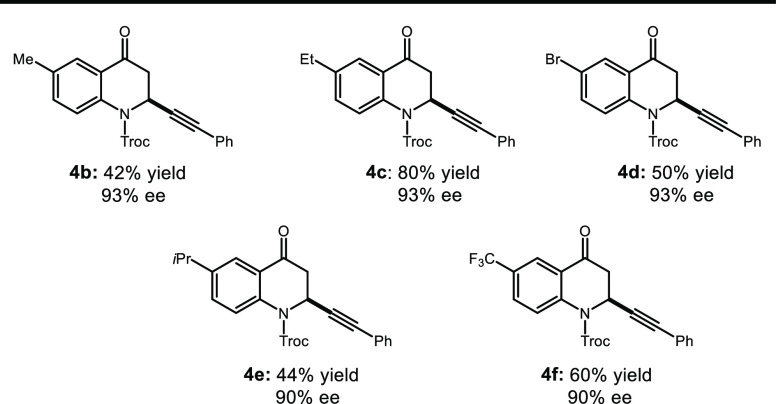

The absolute configuration of the newly formed stereocenter in 4j was determined to be S based on X-ray crystallographic analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of (S)-4j.

From this, the remaining substrates were also reasoned to favor the S enantiomer as the major product by analogy. A possible reaction pathway14 and off-cycle racemization route are depicted in Scheme 4. We hypothesize that the ligand initially coordinates to CuI to give complex I. The reaction of I with phenyl acetylene and Cy2NEt provides copper acetylide II, which can then react with quinolinium ion 2 (formed in situ with TIPSOTf) in the proposed enantio-determining step to furnish 5. Although unlikely, 5 may also undergo a racemization process16 that goes through intermediate 7 to generate opposite product enantiomer 6. Both 5 and 6 may then yield their respective final products upon treatment with HCl.

Scheme 4. Plausible Reaction Pathway.

Given previous pieces of evidence of Lewis-acid induced racemization or the presence of higher-order copper/ligand complexes in similar systems,15 relevant mechanistic studies were carried out to help rule out other potential reaction pathways. To probe for an alternative elimination pathway, product S-4a was subjected to the standard alkynylation conditions with or without alkyne. As shown by the data in Scheme 5, racemization of the product was not observed. Aside from this, a series of standard alkynylation reactions with model substrate 1 and phenyl acetylene 3 were conducted in the presence of L2 with varying enantiopurities (Figure 3).

Scheme 5. Racemization Study.

Figure 3.

Linear effect of alkynylation of substrate 1 using (S,S)-L2 with different ee values with a 96 h reaction time in MTBE.

A linear effect was observed in this alkynylation reaction, which is indicative of no catalyst self-assimilation but does not exclude the possibility a different copper catalyst species in the catalytic cycle.

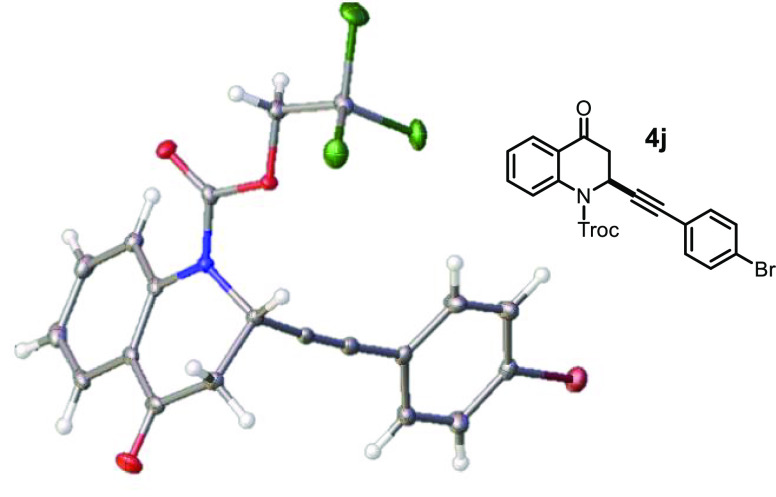

To demonstrate the synthetic utility of our newly generated highly enantioenriched 2-alkynylated dihydroquinolines, several transformations were further carried out to construct an array of biologically significant chiral compounds. The alkynylated product 4a (97% ee after recrystallization) could be diastereoselectively converted into an indoline 9 (Scheme 6A), a prominent motif in many biological alkaloids.22

Scheme 6. Select Synthetic Manipulations of 4.

The scalability of our robust alkynylation method was illustrated in the synthesis of the di-fluorinated analogue of cuspareine (Scheme 6B). Dihydroquinoline 4t could be readily prepared in 64% yield and 90% ee. An unprecedented hydrogenative transesterification of Troc by Pd/C with one atmosphere of H2 in methanol, followed by treatment with LiAlH4, delivered di-fluorinated cuspareine analogue 11 in 34% yield and 89% ee (unoptimized) over two steps.

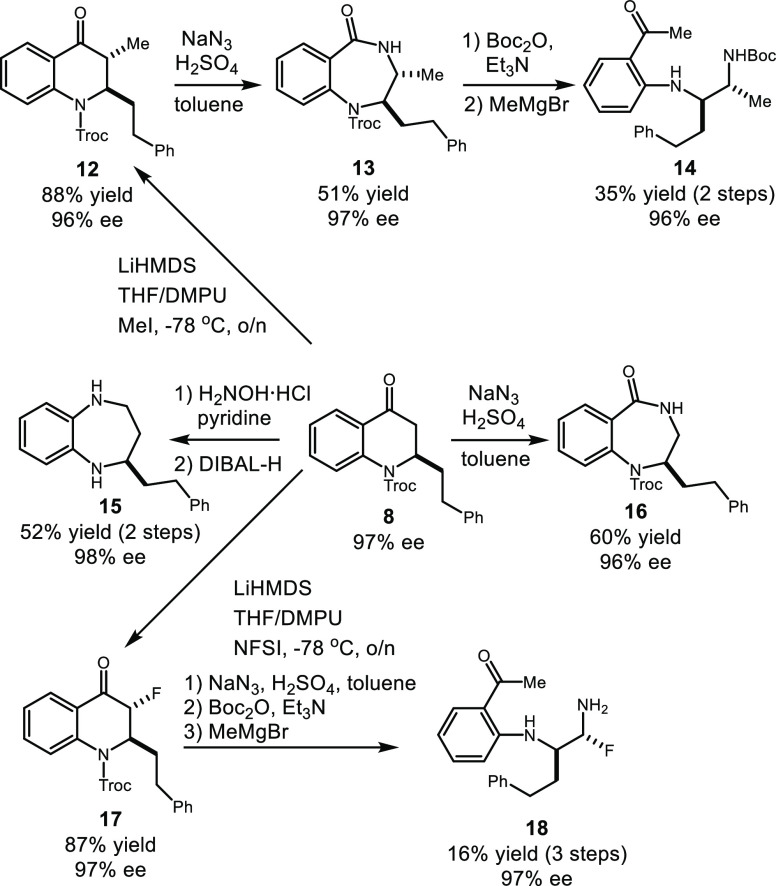

The selective hydrogenation of the internal alkyne by Pd/C with one atmosphere of H2 was achieved when switching methanol to EtOAc to afford ketone 8, which could be further transformed into chiral seven-membered heterocycles and 1,2-diamines (Scheme 7).17−19,21,22 The Schmidt rearrangement of quinolone 8 furnished the core structure of a selective inhibitor of mitochondrial F1F0 ATP hydrolase 16 in 60% yield and 96% ee.20 In contrast, 1,5-benzodiazepine 15, another important skeleton frequently encountered in medicinal chemistry, was generated in 52% yield and 98% ee over two steps upon the treatment of pyridine hydrochloride followed by DIBAL-H. A highly diastereoselective electrophilic procedure was successfully developed to introduce alkyl and fluorine substituents at the C3 position of ketone 8, providing the methylated and fluorinated compounds 12 and 17, respectively.21 A similar Schmidt rearrangement converted 12 into 7-membered heterocycle 13, which upon Boc-protection and subsequent Grignard addition rendered trans chiral 1,2-diamine 14 in 35% yield and 96% ee over 2 steps. Correspondingly, the previously inaccessible and valuable fluorinated trans 1,2-diamine 18 was obtained in 16% yield and 97% ee over 3 steps via the same sequence. To the best of our knowledge, our report represents the first syntheses of those chiral 1,2-diamines in a highly diastereo- and enantioselective manner.

Scheme 7. Select Synthetic Manipulations of 8.

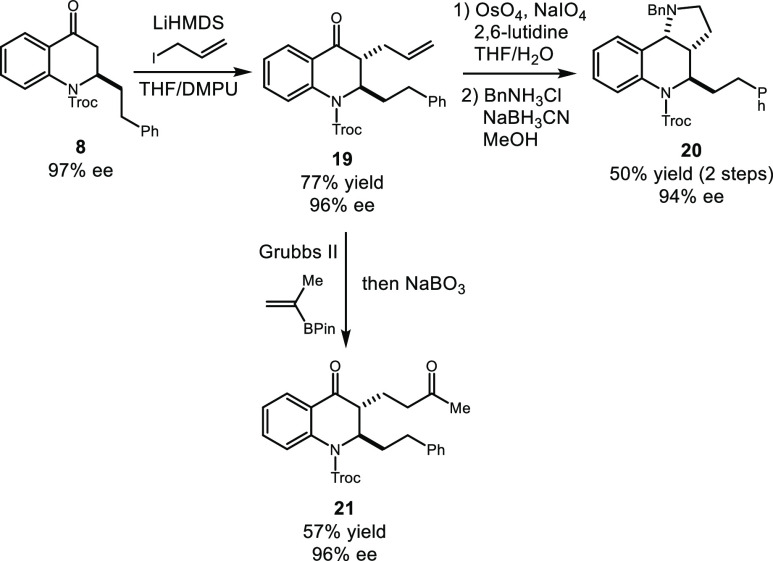

Finally, martinellic acid and levonantradol analogues (20 and 21) were accessed with highly diastereoselective and enantioselective controls (Scheme 8). An allyl substituent was selectively installed to generate alkene 19 in 77% yield and 96% ee, which underwent an oxidative cleavage of the terminal alkene followed by a double reductive amination using benzyl amine and sodium cyanoborohydride to give rise to martinellic acid derivative 20 in 50% yield and 94% ee in a two-step sequence. Cross-metathesis of alkene 29 with commercially available isopropenylboronic acid pinacol ester in the presence of Grubbs second-generation catalyst followed by the oxidation of the resulting vinylboronate with sodium perborate afforded diketone 21 with no erosion of enantioselectivity (57% yield and 96% ee), the precursor that could lead to a levonantradol analogue via Robinson annulation.

Scheme 8. Select Synthetic Manipulations of 8.

In summary, the first highly enantioselective copper bis(oxazoline) catalyzed alkynylation of quinolone via the facial selective dearomatization of in situ generated quinolinium triflates has been developed. The use of commercially available copper iodide and bis(oxazoline) ligands in MTBE with Troc-protected quinolone is key for the success of this reaction. This robust protocol features low catalyst loading (5 mol %) and broad substrate scope with variable functional groups. In most cases, high enantioselective controls were achieved with moderate to excellent yields. The application of early stage DFT calculations expedited the identification of the optimal ligand in a rational way. The synthetic potential of 2-alkynylated dihydroquinolines were exhibited in the syntheses of a diverse array of biologically relevant chiral N-heterocyclic alkaloids and 1,2-diamines. The applications of this novel useful methodology in the syntheses of N-chiral natural products are ongoing in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

NIH NIGMS and the NSF NRT are gratefully acknowledged for the partial funding of this work. A.S. is grateful for her experience as an NSF REU trainee. Generous allocations of computational resources were provided by the Ohio Supercomputer Center.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c01536.

Experimental details and characterization data (PDF)

Author Contributions

Y.G. and T.A.B. equally contributed. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

NIH (1R35GM12480401), NSF REU (1659529), and NSF NRT (2021871).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Asolkar R. N.; Schröder D.; Heckmann R.; Lang S.; Wagner-Döbler I.; Laatsch H. Helquinoline, a New Tetrahydroquinoline Antibiotic from Janibacter limosus Hel 1. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 17–23. 10.7164/antibiotics.57.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joss R. A.; Galeazzi R. L.; Bischoff A.; Do D. D.; Goldhirsch A.; Brunner K. W. Levonantradol, a new antiemetic with a high rate of side-effects for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1982, 9, 61–64. 10.1007/bf00296765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakotoson J.; Fabre N.; Jacquemond-Collet I.; Hannedouche S.; Fourasté I.; Moulis C. Alkaloids fromGalipea officinalis. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 762–763. 10.1055/s-2006-957578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherup K. M.; Ransom R. W.; Graham A. C.; Bernard A. M.; Salvatore M. J.; Lumma W. C.; Anderson P. S.; Pitzenberger S. M.; Varga S. L. Martinelline and Martinellic Acid, Novel G-Protein Linked Receptor Antagonists from the Tropical Plant Martinella iquitosensis (Bignoniaceae). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 6682–6685. 10.1021/ja00130a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews on 4-quinolones and their derivatives, see:; a Nibbs A. E.; Scheidt K. A. Asymmetric Methods for the Synthesis of Flavanones, Chromanones, and Azaflavanones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 449–462. 10.1002/ejoc.201101228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ahmed A.; Daneshtala M. Nonclassical biological activities of quinolone derivatives. J. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 15, 52–72. 10.18433/j3302n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Welsch M. E.; Snyder S. A.; Stockwell B. R. Privileged scaffolds for library design and drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 347–361. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Michael J. P. Indolizidine and quinolizidine alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 139–165. 10.1039/b612166g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For citations on related intramoleculer aza-Michael reactions:; a Saito K.; Moriya Y.; Akiyama T. Chiral Phosphoric Acid Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis of 2-Substituted 2,3-Dihydro-4-quinolones by a Protecting-Group-Free Approach. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3202–3205. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu X.; Lu Y. Asymmetric Synthesis of 2-Aryl-2,3-dihydro-4-quinolones via Bifunctional Thiourea-Mediated Intramolecular Cyclization. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5592–5595. 10.1021/ol102519z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu X.; Lu Y. Bifunctional thiourea-promoted cascade aza-Michael-Henry-dehydration reactions: asymmetric preparation of 3-nitro-1,2-dihydroquinolines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 4063–4065. 10.1039/c0ob00223b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kanagaraj K.; Pitchumani K. Per-6-amino-β-cyclodextrin as a Chiral Base Catalyst Promoting One-Pot Asymmetric Synthesis of 2-Aryl-2,3-dihydro-4-quinolones. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 744–751. 10.1021/jo302173a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Cheng S.; Zhao L.; Yu S. Enantioselective Synthesis of Azaflavanones Using Organocatalytic 6-endo Aza-Michael Addition. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014, 356, 982–986. 10.1002/adsc.201300920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Harutyunyan S. R. Highly Enantioselective Catalytic Addition of Grignard Reagents to N-Heterocyclic Acceptors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12950–12954. 10.1002/anie.201906237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani R.; Yamagami T.; Kimura T.; Hayashi T. Asymmetric Synthesis of 2-Aryl-2,3-dihydro-4-quinolones by Rhodium-Catalyzed 1,4-Addition of Arylzinc Reagents in the Presence of Chlorotrimethylsilane. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5317–5319. 10.1021/ol052257d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H.; Kume T.; Yamamoto Y.; Akiba K. Reaction of 4-t-butyldimethylsiloxy-1-benzopyrylium salt with enol silyl ethers and active methylenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 6355–6358. 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)91372-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For citations on enantioselective alkylation and alkynylation of 4-siloxybenzopyrylium triflates:; a Guan Y.; Attard J.; Mattson A. E. Copper Bis(oxazoline)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Alkynylation of Benzopyrylium Ions. Chem.–Eur. J. 2020, 26, 1742–1747. 10.1002/chem.201904822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guan Y.; Buivydas T. A.; Lalisse R. F.; Attard J. W.; Ali R.; Stern C.; Hadad C. M.; Mattson A. E. Robust, Enantioselective Construction of Challenging, Biologically Relevant Tertiary Ether Stereocenters. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6325–6333. 10.1021/acscatal.1c01095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hardman-Baldwin A. M.; Visco M.; Wieting J.; Stern C.; Kondo S.; Mattson A. E. Silanediol-Catalyzed Chromenone Functionalization. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3766–3769. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestro A.; Lemaire S.; Harutyunyan S. R. Cu(I)-Catalyzed Alkynylation of Quinolones. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 1228–1231. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For citations on the level of theory, see:; a Becke A. D. Density-Functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Stephens P. J.; Devlin F. J.; Chabalowski C. F.; Frisch M. J. Ab Initio Calculation of Vibrational Absorption and Circular Dichroism Spectra Using Density Functional Force Fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kim K.; Jordan K. D. Comparison of Density Functional and MP2 Calculations on the Water Monomer and Dimer. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 10089–10094. 10.1021/j100091a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Nicklass A.; Dolg M.; Stoll H.; Preuss H.; Nicklass A.; Dolg M.; Stoll H.; Preuss H. Ab Initio Energy-Adjusted Pseudopotentials for the Noble Gases Ne through Xe : Calculation of Atomic Dipole and Quadrupole Polarizabilities. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 8942–8952. 10.1063/1.468948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Hariharan P. C.; Pople J. A. The Influence of Polarization Functions on Molecular Orbital Hydrogenation Energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. 10.1007/bf00533485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Ditchfield R.; Hehre W. J.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. 10.1063/1.1674902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Gordon M. S. The Isomers of Silacyclopropane. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1980, 76, 163–168. 10.1016/0009-2614(80)80628-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Hariharan P. C.; Pople J. A. Accuracy of AHnequilibrium geometries by single determinant molecular orbital theory. Mol. Phys. 1974, 27, 209–214. 10.1080/00268977400100171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Hehre W. J.; Ditchfield R.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian-Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257–2261. 10.1063/1.1677527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Garcia J.; Johnson E. R.; Keinan S.; Chaudret R.; Piquemal J.-P.; Beratan D. N.; Yang W. NCIPLOT: A Program for Plotting Noncovalent Interaction Regions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 625–632. 10.1021/ct100641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For related reactions that support this hypothesized pathway, see:; a Srinivas H. D.; Maity P.; Yap G. P.; Watson M. Enantioselective Copper-Catalyzed Alkynylation of Benzopyranyl Oxocarbenium Ions. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 4003–4016. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhong K.; Shan C.; Zhu L.; Liu S.; Zhang T.; Liu F.; Shen B.; Lan Y.; Bai R. Theoretical Study of the Addition of Cu-Carbenes to Acetylenes to Form Chiral Allenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5772–5780. 10.1021/jacs.8b13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For citations on non-linear effects:; a Dasgupta S.; Rivas T.; Watson M. P. Enantioselective Copper(I)-Catalyzed Alkynylation of Oxocarbenium Ions to Set Diaryl Tetrasubstituted Stereocenters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14154–14158. 10.1002/anie.201507373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu Y.; Yi Z.; Yang X.; Wang H.; Yin C.; Wang M.; Dong X.-Q.; Zhang X. Efficient Access to Chiral 2-Oxazolidinones via Ni-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation: Scope Study, Mechanistic Explanation, and Origin of Enantioselectivity. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11153–11161. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Dasgupta S.; Liu J.; Shoffler C. A.; Yap G. P.; Watson M. P. Enantioselective, Copper-Catalyzed Alkynylation of Ketimines To Deliver Isoquinolines with α-Diaryl Tetrasubstituted Stereocenters. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 6006–6009. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Girard C.; Kagan H. B. Nonlinear Effects in Asymmetric Synthesis and Stereoselective Reactions: Ten Years of Investigation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2922–2959. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley E. R.; Sherer E. C.; Pio B.; Orr R. K.; Ruck R. T. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Resolution Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of β-Chromanones by an Elimination-Induced Racemization Mechanism. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1446–1451. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G.; Li G.; Huang J.; Fu D.; Nie X.; Cui X.; Zhao J.; Tang Z. Regioselective, Diastereoselective, and Enantioselective One-Pot Tandem Reaction Based on an in Situ Formed Reductant: Preparation of 2,3-Disubstituted 1,5-Benzodiazepine. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 5110–5119. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c03064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan X.-C.; Zhang C.-Y.; Zhong F.; Tian P.; Yin L. Synthesis of chiral anti-1,2-diamine derivatives through copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric α-addition of ketimines to aldimines. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4473. 10.1038/s41467-020-18235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-Y.; Li S.; Fan T.; Zhang Z.-J.; Song J.; Gong L.-Z. Enantioselective Formal [4 + 3] Annulations to Access Benzodiazepinones and Benzoxazepinones via NHC/Ir/Urea Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14388–14394. 10.1021/acscatal.1c04541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann L. G.; Ding C. Z.; Miller A. V.; Madsen C. S.; Wang P.; Stein P. D.; Pudzianowski A. T.; Green D. W.; Monshizadegan H.; Atwal K. S. Benzodiazepine-based selective inhibitors of mitochondrial F1F0 ATP hydrolase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 35, 1031–1034. 10.1002/chin.200423178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina Betancourt R.; Phansavath P.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V. Straightforward Access to Enantioenriched cis-3-Fluoro-dihydroquinolin-4-ols Derivatives via Ru(II)-Catalyzed-Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation/Dynamic Kinetic Resolution. Molecules 2022, 27, 995. 10.3390/molecules27030995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiral indolines and tetrahydroquinolines; a Campbell E. L.; Zuhl A. M.; Liu C. M.; Boger D. L. Total Synthesis of (+)-Fendleridine (Aspidoalbidine) and (+)-1-Acetylaspidoalbidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3009–3012. 10.1021/ja908819q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li J.; Wang T.; Yu P.; Peterson A.; Weber R.; Soerens D.; Grubisha D.; Bennett D.; Cook J. M. General Approach for the Synthesis of Ajmaline/Sarpagine Indole Alkaloids: Enantiospecific Total Synthesis of (+)-Ajmaline, Alkaloid G, and Norsuaveoline via the Asymmetric Pictet–Spengler Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6998–7010. 10.1021/ja990184l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.