Highlights

-

•

Three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G related immunogenic lncRNA subtypes in OC were identified.

-

•

The three subtypes showed heterogeneity in terms of prognosis, mutation pattern, TIME component, and response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy.

-

•

A set of risk predictive system forming from 10 lncRNA for OC was developed.

-

•

Risk predictive system we developed could reflect the prognosis and TME characteristics of OC populations with different clinical characteristics to some extent.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, RNA methylation, Mutation, Tumor immune microenvironment, Chemotherapy

Abstract

Introduction

Complex outcome of ovarian cancer (OC) stems from the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) influenced by genetic and epigenetic factors. This study aimed to comprehensively explored the subclasses of OC through lncRNAs related to both N6-methyladenosine (m6A)/N1-methyladenosine (m1A)/N7-methylguanosine (m7G)/5-methylcytosine (m5C) in terms of epigenetic variability and immune molecules and develop a new set of risk predictive systems.

Material and methods

The lncRNA data of OC were collected from TCGA. Spearman correlation analysis on lncRNA data of OC with immune-related gene expression and with m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G were respectively conducted. The m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G related immune lncRNA subtypes were identified on the basis of the prognostic lncRNAs. Heterogeneity among subtypes was evaluated by tumor mutation analysis, tumor microenvironment (TME) component analysis, response to immune checkpoint blocked (ICB) and chemotherapeutic drugs. A risk predictive system was developed based on the results of Cox regression analysis and random survival forest analysis of the differences between each specific cluster and other clusters.

Results

Three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes of OC showing distinct differences in prognosis, mutation pattern, TIME components, immunotherapy and chemotherapy response were identified. A set of risk predictive system consisting of 10 lncRNA for OC was developed, according to which the risk score of samples in each OC dataset was calculated and risk type was defined.

Conclusions

This study classified three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes with distinct heterogeneous mutation patterns, TME components, ICB therapy and immune response, and provided a set of risk predictive system consisted of 10 lncRNA for OC.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) has a lifetime risk of about 2% for women and is the second most common factor leading to gynecological cancer deaths in women worldwide [1,2]. The outcome of OV is also complicated because the disease is often diagnosed at late stage and consists of several subtypes with different biological and molecular properties showing inconsistencies in the availability and accessibility of treatment [2]. The complexity of these malignant tumors stems from the microenvironment affected by genetic factors. And the complexity also varies according to the change of epigenetic factors [3]. Understanding tumor microenvironment (TME) and epigenetic characteristics is the key to the diagnosis, treatment options and survival of OC.

The immune components of tumor microenvironment account for a large part of innate immune cells, adaptive immune cells, extracellular immune factors and cell surface molecules. All immune components are clearly defined as tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) [4]. Immune contexture of TIME is a key coordinating factor in the progression of OC and a necessary target for combined therapy [5]. Research based on the immune contexture of TIME has also successfully promoted the development of immunotherapies. But other important issues, such as how to evaluate patients’ benefit from therapeutic interventions, should be addressed, and there is an urgent need to combine advanced sequencing techniques and image-based approaches to the study of the genome of clinical tumor samples and preclinical models [6].

RNA methylation in epigenetic variability plays an important role in tumor biology, including proliferation, metastasis, metabolism, apoptosis and therapeutic drug resistance. The most common RNA modifications are N6-methyladenosine (m6A), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N7-methylguanosine (m7G) and 5-methylcytosine (m5C) [7]. Generally speaking, RNA modification occurs on mRNA, tRNA and rRNA. Recent reports have found that lncRNAs also undergo extensive RNA modification, including m6A, m1A and m5C [8,9]. m6A modification enriching in rhPM1-AS1 improves the methylated transcriptional stability of lncRNA rhPM1-AS1 and then promotes the proliferation and metastasis of OC cells by regulating the miR-596-LETM1 axis [10]. Zhang et al. revealed the role of lncRNA regulated by m5C methylation in the prognosis of bladder cancer [11]. However, the relationship between lncRNA and tumor immunity influenced by RNA modification has not been widely studied.

In this study, the RNA-seq of lncRNA data for OC were extracted from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) public database, and Spearman correlation analysis was conducted on m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G and immune molecules, respectively. The m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes was obtained to classify OC patients, and a set of risk predictive system was established according to the difference in expression data of subtypes. By identifying the prognosis and immunotherapy response of each sample of risk type, this study provides a new perspective for the management of OC.

Materials and methods

Collection of OC dataset and extraction of expression profile

Data sets of OC samples were retrieved in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), Gene-Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC, https://icgc.org) databases. The processing standard of samples in each dataset was the same, only samples with survival status and survival time of 30 days or longer were retained. The eligible samples in TCGA, GSE102073 in GEO and ICGC were 363, 85 and 93, respectively. We downloaded the latest version of the GTF file from the GENCODE website (https://www.gencodegenes.org/), divided the expression profile of each dataset into mRNA and lncRNA according to the comments in the file, and converted the fragment per kilobase million (FPKM) count into TPM values.

Screening m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA

Spearman correlation test was employed to analyze the correlation between lncRNA expression and immune-related gene expression and the four types of RNA methylation m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G, respectively. Immune-related lncRNAs and m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related lncRNAs were screened according to the threshold of |correlation (cor)| > 0.3 and False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05. The m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA was identified by selecting the common genes between immune-related lncRNA and m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related lncRNA.

Consensus clustering for m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA expression of OC

Based on the expression data of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA in OC and the survival data of samples, m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNAs showing prognostic significance were screened with p<0.05 as the cut-off value by performing conducting univariate Cox regression analysis in "survival" package, followed by subsequent classification using "ConsensusClusterPlus" [12] package. The parameter was clusterAlg= "km", distance = "euclidean", reps=500, pItem=0.8, maxK=9, reps=500, pItem=0.8. The output image included consensus distribution function (CDF) curve, CDF delta area curve and consensus matrix. The purpose of drawing CDF curve and CDF delta area curve was to find k where the distribution reached the approximate maximum value to represent the maximum stability. Consensus matrix helps find the 'cleanest' cluster partition where items either cluster together to give a high consensus (dark blue colour) or do not cluster together to give a low consensus (white) [12].

Mutation analysis of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes

The analyzed mutation indexes of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes included single nucleotide variation (SNV), tumor mutation burden (TMB), mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH), homologous recombination defects (HRD). SNV is the variation of a single nucleotide at the genome level and is the main form of genetic variation in the genome [13], including missense mutation, frame shift ins, nonsense mutation, in frame ins, frame shift del, splice site, in frame del and multi hit. TMB is defined as the number of mutations per DNA megabases excluding SNV, germline, copy number variation, and structural variation [14,15]. MATH is a simple quantitative measure of genetic heterogeneity within tumors and is commonly applied in exome sequencing data from normal and tumor samples so that tumor-specific mutations can be identified [16]. HRD refers to the loss of cell ability to repair DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination and is closely associated with BRCA1/2 mutations. HRD score is defined as the unweighted sum of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) score, telomeric allelic imbalance (TAI) score and large-scale state transitions (LST) score [17]. The SNV data set of level 4 came from GDC (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), these abrupt data were processed using MuTect2 software [18]. The R package "maftools" was utilized to draw the mutation waterfall diagram for the mutant genes, and the tmb function and inferHeterogeneity function of the package were adopted to exmaine TMB and MATH, respectively. Scores for HRDs was calculated by referring to the study of Thorsson et al. [19].

TIME activity analysis

ESTIMATE quantified the stromal score and immune score of the tumor sample according to the characteristics of stromal cells and immune cells that made up the main non-tumor components of the tumor sample and combined to reflect the tumor purity [20]. This algorithm was applied to the OC samples in this study. CIBERSORT [21] analyzed the relative scores of 22 immune cells in the OC gene expression profile from TCGA according to "leukocyte signature matrix (LM22)". Seven steps of effective killing of cancer cells through anticancer immune response are defined as anticancer immune cycle [22]. The characteristic genes of anticancer immune cycle were obtained from TIP [23]. The 29 functional gene expression signatures (Fges) defined by the major functional components and immune, stromal as well as some other cellular populations of the tumor represent the comprehensive characteristics of TME [24]. The anti-cancer immune response steps and 29 Fges scores of each sample were calculated using single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA).

Development and verification of a set of risk predictive system based on differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) between subtypes

The DElncRNA between each specific cluster and other clusters was analyzed by "limma" package [25]. The genes filtered through the significant threshold FDR < 0.05 and |log2FC| > log2 (1.5) were used for further univariate Cox regression analysis. The rfsrc function and var.select function in "randomForestSRC" packetage were applied to the prognostically related DElncRNAs obtained from univariate Cox regression analysis to develop a random survival forest model. The MASS package was then used to simplify the DElncRNAs and the risk coefficient was calculated with the help of multivariate Cox retrospective analysis. The expression of each DElncRNA was multiplied by its risk coefficient and summed to obtain the risk score for each sample. After standardizing the risk score by z-score, the samples with standardized risk score 〈 0 were defined as high-risk types, while those with 〉 0 were defined as low-risk subtypes. Kaplan-Meier log-rank test was performed to calculate significant difference in survival between high-risk type and low-risk type, and further combined with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to verify the accuracy of the risk prediction system.

Prediction of degree of response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy and chemotherapy

ICB is the most common immunotherapy. Considering the expression of immune checkpoint is an important part of the prediction of ICB treatment, according to the information of immune activation and immune inhibition checkpoints from a past study [26], the corresponding immune checkpoint expression in risk score types was analyzed. A variety of methods have emerged to predict immunotherapy, such as Th1/IFN γ gene signature for predicting the outcome of immunotherapy with MAGE-A [27], T cell inflamed gene expression profile (GEP) [28], and Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) [29] for predicting first-line anti-PD1 or anti-CTLA4 response. The correlation between ssGSEA score and risk score of these models was calculated. IC50 information of five drugs related to the treatment of OC was obtained from Genome of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database and input into "pRRophetic" package [30], and a model was produced by ridge regression to predict the responses of samples to the five drugs.

Collection of clinical OC tissues

A total of 30 OC tissue samples were obtained from patients who underwent oophorectomy at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Guangzhou Women and Children's Medical Center. The Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Women and Children's Medical Center approved the current study (082B00), which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Prior to the inclusion into the study, all the patients provided informed consent for the utilization of their tissues and data.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was employed for the detection of CD45 expression in OC tissues. In brief, paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 4-μm sections and subjected to deparaffinization with xylene and rehydration in a graded alcohol series, followed by incubation in an oven (65 °C) for 40 min (min). Sequential endogenous peroxidase blocking and antigen retrieval were carried out. Tissue slices were incubated with anti-CD45 antibody (1:100, Abcam, USA) in a humid chamber at 4 °C for 12 h (h). Subsequently, the slices were treated with anti-rabbit secondary antibody and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate, and developed with DAB. Then, the slices were stained with Mayer's hematoxylin, dehydrated, sealed with neutral size, and visualized under an Olympus CX31 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Two pathologists blinded to the clinical characteristics of the OC patients independently evaluated the IHC results using the H-score system. CD45-positive cell intensity was assigned with a score of 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong). The percentage (0–100%) of stained cells was multiplied by the dominant intensity pattern of staining (0–3), and the H-score values ranged from 0 to 300. The expression of CD45 was dichotomized based on the median value.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

The extraction of total RNA was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Thereafter, cDNA synthesis was performed with HiScript QRT SuperMix (Vazyme) for qPCR. An SYBR Green PCR Kit (Vazyme) was used in qPCR. The list of all the RT-qPCR primers used in this study are presented below:

PCOLCE-AS1-forward:5′-CTAGGCTTGGGGGACCTCTG-3′, PCOLCE-AS1-reverse:5′-TAAGAGATGGGTCCTGGGCAA-3′; OCIAD1-AS1-forward:5′-TCTAGCAGAGTCCTTGACACC-3′, OCIAD1-AS1-reverse:5′-ACCTGTGTGTTCTACCATCAATCA-3′.

Statistical analysis

All the statistics were analyzed by R program. The difference between two and three groups of continuous variables was measured by Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Kruskal-Wallis tests, respectively. The survival curve was plotted by Kaplan-Meier method, and the survival difference was compared by log-rank tests. The correlation between variables was tested by Spearman correlation analysis. Statistical significance was measured using p value, with p < 0.05 showing a statistical significance.

Results

Identification of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA with prognostic significance for OC

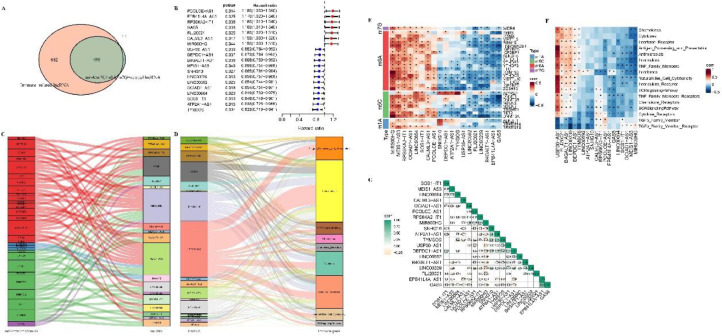

After distinguishing the lncRNA expression profile of OC samples from TCGA, the correlation between lncRNA and m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G and immune-related genes was analyzed. Among them, a total of 510 lncRNAs were significantly related to m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G, 1181 lncRNAs were significantly related to immune genes, and 499 lncRNAs of the two parts, that is, m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA, were in intersection (Fig. 1A). Univariate Cox regression analysis identified that 19 lncRNAs (m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA) showing a correlation of p <0.05 with sample survival were considered as having a prognostic value (Fig. 1B). Among the 19 lncRNAs, those whose main modification type was m6A included PCOLCE-AS1, EPB41L4A-AS1, RPS6KA2-IT1, GAS5, FLJ20021, CALML3-AS1, MIR600HG, USP30-AS1, B4GALT1-AS1 and MEIS1-AS3. m1A occurred only in SNHG10 and MEIS1-AS3. Excepted for PCOLCE-AS1, m5C modification was found in the rest 18 lncRNA, and this RNA modification was the main type of RNA modification for DEPDC1−AS1, LINC00592, ATP2A1−AS1, LINC00239, OCIAD1−AS1, LINC00664, and TYMSOS. M7G existed only in FLJ20021 and MIR600HG, and was not the main type of RNA modification in these two lncRNAs (Fig. 1C). USP30-AS1 was the most important immune gene among the 19 lncRNAs, because it was the main regulatory gene in most immune regulatory pathways, including in antigen processing and presentation, antimicrobials, cytokine receptors, cytokines and natural killer cell cytotoxicity and so on (Fig. 1D). Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated that MIR600HG, MEIS1-AS3, RPS6KA2-IT1, OCIAD1-AS1, LINC00664 were significantly positively correlated with most m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G, while FLJ20021, LINC00239, B4GALT1-AS1, GAS5 and m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G were significantly negatively correlated (Fig. 1E). USP30-AS1, FLJ20021, LINC00239, B4GALT1-AS1 were positively correlated with ssGSEA scores of immune molecules (Fig. 1F). Moreover, there was a certain degree of correlation among the 19 lncRNAs (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Identification of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA with prognostic significance for OC. A: The intersection of lncRNA significantly related to m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G and lncRNA significantly related to immune genes. B: Univariate Cox regression analysis showed the p value and hazard ratio (HR) of 19 m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA with prognostic significance. C: The alluvial map shows four types of RNA modifications in 19 lncRNAs, 19 lncRNA are represented by different color boxes on the right, and RNA modification types are also represented by different color boxes on the left, red for m6A, blue for m1A, green for m5C, purple for m7G. D: The alluvial map shows the association between 19 lncRNA and immunity, with 19 lncRNA on the left and immune molecular pathways on the right. E: Spearman correlation matrices of 19 lncRNAs and m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G. F: Correlation between m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA that have prognostic significance for OC and immune-related molecular functions or pathways that have prognostic significance for OC. G: Spearman correlation analysis among 19 lncRNA.

Three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G related immune lncRNA subtypes were identified by consensus clustering

The expression of 19 prognostic m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNAs in the OC data set of TCGA served as the input for consensus clustering analysis. When k = 3, both the CDF curve and the CDF delta area curve showed that choosing k = 3 would produce the optimal clustering results (Fig. 2A, 2B). Therefore, we generated a consensus matrix at k=3 when a clear boundary between the three clusters and a high degree of consistency within the cluster could be observed (Fig. 2C). Among the OC samples from TCGA, 94 samples belonged to C1, 153 samples were classified as C2, and 116 samples belonged to C3. The survival probability of the three clusters manifested significant differences. Under the same survival chances, C1 had the shortest survival time, followed by C2 and C3 (Fig. 2D). Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis demonstrated that C1, C2 and C3 subtypes could be clearly distinguished from each other (Fig. 2E). All the 19 lncRNAs defining 3 subtypes had significant differences in gene expression between the three clusters (Fig. 2F). Most m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related genes also showed significant expression differences among the three clusters (Fig. 2G). We also detected significant differences in the ssGSEA score of immune molecules among the three subtypes, and almost all of them had the highest level in C3 (except for TGF β family member and TGF β family member receptor) (Fig. 2H). The results displayed in Fig. 2F-2H were presented in the form of heat maps in Fig. 2I, and the trends were consistent with the results described in the box diagram.

Fig. 2.

Three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G related immune lncRNA subtypes were identified by OC consensus clustering. A, B: CDF curves and the delta area of the relative change in the area under the CDF curve for k = 2–9, respectively. C: The consensus matrix for k = 3. D: Survival changes of each cluster from the OC dataset of TCGA. E: PCA for three subtypes in the OC dataset from TCGA. F: The expression levels of 19 lncRNAs in the three subtypes were compared by log2(TPM+1) value. G: The expression level of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related genes in each subtype. H: The ssGSEA score of immune molecules in the three subtypes. I: The heat map shows the expression patterns of immune molecules, m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA and m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related genes in each subtype.

Mutation patterns of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes

The genome changes underlying three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes were summarized in terms of TMB, MATH, HRD, and SNV. Although TMB and MATH were present in each m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-associated immune lncRNA subtype, none of them showed significant differences among the three subtypes (Fig. 3A, 3B). However, there were significant differences in HRD score of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, with C3 having the highest HRD score and C1 having the lowest HRD score (Fig. 3C). Phenotypic distribution of immunoreactive phenotypes in C3 was significantly higher than that in C1 and C2, while the proportion of mesenchymal and proliferative phenotypes in C3 was significantly lower than that in C1 and C2 (Fig. 3D). Among the six immune subtypes defined by Thorsson, C2 was the highest in proportion among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, but this immune subtype showed a significantly different proportion among the three defined subtypes, with the proportion in C3 being significantly higher than that in C1 and C2 (Fig. 3E). The three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes also showed their own specific SNV patterns. TP53 and TTN were the two genes with the highest mutation rate among the three subtypes, with the highest mutation rate being found in C2. The main mutation type of TP53 in each subtype was missense mutation. The main mutation pattern of TTN in C2 was missense mutation, and the main mutation type in C3 was multi hit, and the types of missense mutation and multi hit mutation of TTN were comparable in C1. But the overall SNV of C3 was the highest (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Mutation patterns of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. A: TMB of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. B: MATH of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. C: HRD scores of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. D: The distribution of phenotypic differences among three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. E: The distribution proportion of the six immune subtypes defined by Thorsson in the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes we defined. F: The waterfall chart shows the mutation rate and mutation type of 20 genes in each m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtype according to the mutations proportion from high to low.

Different immune microenvironment of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes

As the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes had different mutation patterns and somatic variation was related to immune infiltration, here we compared the immune microenvironment of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. According to the results of ESTIMATE analysis, stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score and tumor purity all showed significant differences among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. Among them, the first three TME score were the highest in C3, but the tumor purity was the lowest the three subtypes (Fig. 4A). The highest content of immune cell in the three subtypes of TME was M0 macrophages, resting memory CD4+ T cells, M2 macrophages, M1 macrophages, CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs). And the abundance of resting memory CD4+ T cells, M0 macrophages and Tregs in C1 and C2 was significantly higher than that in C3. In contrast, the abundance of CD8+ T cells and M1 macrophages was significantly higher in C3 than in C1 and C2 (Fig. 4B). The seven steps of anti-tumor immune response also showed significantly different enrichment scores among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, with that in C3 being the highest (Fig. 4C). For 29 Fges, the ssGSEA score in C3 was significantly higher than that in C1 and C2 (Fig. 4D). On the whole, compared with C1 and C2, the activities of 29 Fges and anti-tumor immune response steps in C3 were significantly improved (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Different immune microenvironments of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. A: ESTIMATE analysis showed stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score and tumor purity of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. B: The abundance of 22 immune cells in 3 m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. C: The enrichment scores of the seven steps of anti-tumor immune response in 3 m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. D: The change trend of 29 Fges in 3 m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. E: The ssGSEA score of 29 Fges and anti-tumor immune response steps in each m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtype.

Different response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes

The performance of indicators related to ICB treatment response among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes was evaluated. The three subtypes showed different T cell inflamed GEP score, Th1/IFN γ ssGSEA score and cytolytic activity. Compared with C1 and C2, the levels of these three ICB treatment response-related indexes in C3 were significantly higher (Fig. 5A-5C). Compared with C1, the overall expression level of immune inhibition and immune activation checkpoint genes were significantly increased in C3, which could be observed in both heat maps and mountain maps (Fig. 5D, 5E). TIDE for predicting immunotherapy response showed significant differences in T cell exclusion score among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. The T cell exclusion score of C1 and C2 was significantly higher than that of C3, and the T cell exclusion score of the first two subtypes was > 0, while the T cell exclusion score of the latter was < 0. The TIDE score of the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes was all above 0 with significant differences. Relative to C1 and C2, the TIDE score of C3 decreased significantly (Fig. 5F). Five drugs (Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Gefitinib, Olaparib) for the treatment of OC were selected for sensitivity study. Each therapeutic drug showed significant differences in estimated IC50 among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, and all of them were the lowest in C3, meaning that the same amount of these five drugs were used in the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes and it was easier to achieve the inhibitory effect on C3 (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

Different response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. A-C: T cell inflamed GEP score, Th1/IFN γ ssGSEA score and cytolytic activity in three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. D: The heat map of immune inhibition and immune activation checkpoint gene expression in three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. E: Mountain map of immune inhibition and immune activation checkpoint gene expression in three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. F: T cell exclusion score and T cell dysfunction score and TIDE score of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtype. G: The sensitivity of Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Gefitinib and Olaparib in three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes.

Generation and validation of a set of risk predictive systems

Due to different molecular characteristics, TME status and therapeutic response of the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, it is necessary to screen differential molecules among the three subtypes. We identified DElncRNAs using differential expression analysis from each m6A/m5C/m1A/ M7G-related immune lncRNA subtype in the OC cohort of TCGA as well as the remaining samples in the cohort. There were 89 DElncRNAs between C1 and non-C1 samples in TCGA OC cohort (Figure S1A), 315 DElncRNAs between C2 and the rest of the samples (Figure S1B), and 391 DelncRNAs between C3 and non-C3 samples in the cohort (Figure S1C). Because of the overlap in these DElncRNAs, all these DElncRNAs actually added up to 507. Among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, a high expression of 507 DElncRNAs was the most obvious in C2 (Figure S1D). Univariate Cox regression analysis on the OC cohort of TCGA demonstrated that 36 out of 507 DElncRNAs were significantly associated with the prognosis of OC, including 11 DelncRNAs significantly associated with poor survival of OC and 25 DelncRNAs associated with good prognosis of OC (Fig. 6A). The minimal depth variable selection of random survival forest model showed that 14 DElncRNAs were the most highly predictive variables (Fig. 6B). The stepAIC method in the MASS package deleted 4 DElncRNAs from the 14 DElncRNAs, and the remaining 10 DElncRNAs were employed to build a risk predictive system (Fig. 6C). The specific formula was as follows: Risk score=0.087 × LINC00189+ (−0.098 × LINC00664) + (−0.174 × LEMD1-AS1) + 0.144 × C9orf106 + 0.139 × GAS5 + (−0.203 × IFNG-AS1) + (−0.138 × TYMSOS) + (−0.231 × OCIAD1-AS1) + 0.08 × RPS6KA2-IT1+0.126 × PCOLCE-AS1. The standardized risk scores of samples in the OC cohort of TCGA, GSE102073 and ICGC were calculated using the risk predictive system and zscore and were divided into two risk types. Whether in TCGA (HR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.6–2.12; p< 0.0001), GSE102073 cohorts (HR: 4.07; 95 CI%: 2.06−8.05; p = 0.00055) or ICGC cohort (HR: 1.64; 95 CI%: 1.28−2.11; p = 0.013), samples with a low-risk subtype showed a significant survival advantage than those with a high-risk subtype (Fig. 6D-6F). In the OC cohort of TCGA, GSE102073 and ICGC, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) based on the risk predictive system was 0.69 ([95% CI]: 0.58–0.8), 0.7 ([95% CI]:57–0.83) and 0.61([95% CI]:0.4–0.82), respectively, and the AUC in 3 years was 0.69 ([95% CI]: 0.63–0.72), 0.88 ([95% CI]: 0.76–0.99) and 0.7 ([95% CI]: 0.59–0.81), respectively; The AUC score was 0.71 ([95% CI]: 0.65–0.78), 0.79 ([95% CI]: 0.6–0.98) and 0.7 ([95% CI]: 0.56–0.84) in 5 years, respectively (Fig. 6G–6I).

Fig. 6.

Generation and validation of a set of risk predictive systems. A: Volcanic maps shows univariate Cox regression analysis of 507 DElncRNAs, the red dot is the DElncRNAs significantly associated with the poor prognosis of OC, and the green dot is the DElncRNAs significantly related to the good prognosis of OC. B: 14 DElncRNA selected by random survival forest model. C: Multivariate Cox regression forest map of 10 DElncRNAs. d-F: The survival difference between the two risk types in OC cohort of TCGA, GSE102073 cohort and ICGC. G-I: ROC curve based on risk predictive system for OC cohort of TCGA, GSE102073 cohort and ICGC.

Prognostic significance of risk predictive system in different clinical characteristics

The risk score of samples with different clinical characteristics was analyzed. Risk score did not show significant difference between the samples with age ≤ 60 years olf and age > 60 years old. In the clinical grade grouping, there was no significant difference in risk score among the four grades. The risk score showed significant difference in the tumor stage group, and the cluster of high tumor stage was accompanied by a high-risk score (Fig. 7A). The risk score showed significant differences among the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes (C1, C2 and C3 according to the descending order of risk score) (Fig. 7B). The main subtypes of the high-risk group were C1 and C2, while the main subtypes of the low-risk group were C2 and C3 (Fig. 7C). The samples were subdivided according to different clinical characteristics, and then the risk score was calculated using the risk prediction system and the prognosis was estimated. The prediction system could not significantly distinguish the survival difference between stage Ⅱ (HR: 7.48; 95 CI%: 0.43−129.3; p = 0.11) and stage Ⅳ (HR: 1.75; 95 CI%: 0.85−3.58; p = 0.12). Risk predictive system showed a strong performance in predicting the survival of stage Ⅲ (HR: 2.31; 95 CI%: 1.7 − 3.16; p<0.0001), G2 (HR: 2.41; 95 CI%: 1.01−5.74; p = 0.041) and G3 (HR: 2.22; 95 CI%: 1.65−2.98; p<0.0001) samples, and could effectively distinguish the prognostic differences between different risk types (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Prognostic significance of risk predictive system in different clinical characteristics. A: The risk score of samples with different clinical characteristics were age and tumor stage and grade from left to right. Age, tumor stage and grade are shown from left to right. B: Risk score of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes. C: The alluvial map shows the sample subtypes that make up the high-risk group and the low-risk group. D: Risk predictive system predictes survival in stage Ⅱ, stage Ⅲ, stage Ⅳ, G2 and G3, respectively.

Comparison of prognostic performance of the risk predictive system and previously published immune-related lncRNA signatures

To evaluate whether our 10 lncRNAs-based prediction signature could perform better in predicting the prognosis of OC, we compared the risk predictive system with three previously published lncRNA signatures for OC, specifically, the signature based on 6 immune-related lncRNAs [31], the signature based on 10 differentially expressed and methylated lncRNAs [32], and the signature based on 29 lncRNA pairs [33]. The lncRNAs in the first two models and the corresponding Cox regression coefficient were respectively used to calculate the risk scores of the samples in the TCGA-OC cohort, and the grouping method was above or below 0 after zscore. According to the lncRNAs in the first two models and the corresponding Cox regression coefficient, the risk scores of the samples in the TCGA-OC cohort were calculated respectively, and the grouping was based on whether zscore was above or below 0. 29. The lncRNA pairs signature was calculated by adding the multiplication between the regression coefficient and the expression of the matched DEirlncRNA pairs, and the high-risk group and low-risk group were distinguished by the cut-off value of the 5-year ROC curve. Any of the three risk score calculations significantly distinguished the overall survival between high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. S2A-2C). By comparing the AUC of the ROC curves, we found that the accuracy of 6 immune-related lncRNAs signature and 10 differentially expressed and methylated lncRNAs signature in predicting 1 -, 3 -, and 5-year OS was not as high as our risk predictive system (Figure S2D-2E). The AUC of 29 lncRNA pairs signature for 1-year, 3-year and 5-year OS were all slightly higher than our risk predictive system (Figure S2F). Additionally, the concordance index (C-index) of our risk prediction system was also significantly higher than that of the 6 immune-related lncRNAs signature and 10 differentially expressed and methylated lncRNAs signature but slightly lower than the 29 lncRNA pairs signature (Figure S2G). Although the prognosis accuracy of 29 lncRNA pairs signature was slightly higher than that of our risk predictive system, the signature involved too many lncRNAs, which was not cost-effective to detect as many as 10 lncRNAs in clinical practice.

The influence of risk predictive system on TME

To understand the effect of risk score on TME, we distinguished the TME characteristics of different risk subtypes. Significant differences in stromal score between high-risk and low-risk types were observed, but we did not find significant differences in immune score and tumor purity between the two risk subtypes. Samples with a high risk exhibited significantly higher stromal scores than those with a low risk score (Fig. 8A). Among the immune cells with high content of TME, helper follicular T cells, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, activated dendritic cells showed significant differences in abundance between the two risk subtypes. Compared with the samples with a high risk, the abundance of helper follicular T cells, M1 macrophages, and activated dendritic cells in the low-risk samples was increased significantly, while that of M2 macrophages was significantly decreased (Fig. 8B). 15 out of the 29 Fges showed different ssGSEA scores between the two risk subtypes, among which immune suppression by myeloid, Treg, B cell, NK cell, effector cells, T cells, Th1 signature, effector cell traffic and tumor proliferation rate had higher ssGSEA score in low-risk samples, while cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), matrix, protumor cytokines and EMT signature were higher in the samples with high-risk subtype (Fig. 8C). Relative to low-risk type, trafficking of immune cells to tumors (step 4) and recognition of cancer cells by T cells (step 6) and killing of cancer cells (step 7) in the seven steps of antitumor immune response were significantly enriched in high-risk subtypes (Fig. 8D). The Spearman correlation analysis on all the above TME-related indicators and risk score showed that risk score was positively correlated with the levels of stromal sore, M2 macrophages and neutrophils. The risk score was significantly negatively correlated with many indexes related to TME, including plasma cells, helper follicular T cells, M1 macrophages and 14 fges score as well as anti-tumor immune response step 3, step 4, step 6 and step 7 (Fig. 8E).

Fig. 8.

The influence of risk predictive system on TME. A: Stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score and tumor purity shown by different risk types. B: The abundance of infiltrating immune cells in different risk types. C: The ssGSEA score difference of 29 Fges between two risk types. D: The difference in ssGSEA score between the two risk types of the 7 steps of the antitumor immune response. E: Spearman correlation analysis between risk score and TME related indexes.

The role of risk score in predicting immunotherapy response and chemotherapy drug sensitivity

To verify the role of risk score in predicting immunotherapy response and chemotherapy drug sensitivity, the correlation between several predictive indexes of immunotherapy-related responses and risk score was analyzed. Risk score was significantly negatively correlated with T cell inflamed GEP score and Th1/IFN γ ssGSEA score and cytolytic activity, but with a lower degree of correlation. Compared with the high-risk samples, the low-risk samples showed significantly elevated T cell inflamed GEP score, Th1/ IFN-γ ssGSEA score and cytolytic activity (Fig. 9A–9C). Immune inhibition checkpoint gene, including ADORA2A, BTLA, CEACAM1, CTLA4, IDO1, LAG3, TIGIT as well as immune activation checkpoint gene CD27 and ICOS, TNFRSF18 all showed a higher expression in low-risk samples than in high-risk samples (Fig. 9D). Correlation analysis also showed significant negative correlation between risk score and them (Fig. 9E). Compared with the samples with a high risk, the low-risk samples had significantly down-regulated CAF and cancer associated M2 macrophages (TAM.M2) scores. However, MDSC, T cell exclusion and T cell dysfunction and TIDE scores did not show significant differences between high- and low-risk samples (Fig. 9F). OC is a tumor closely related to defects in DNA repair mechanisms in which HRD leads to a better response of OC to chemotherapy drugs and targeted drug therapy [34]. Therefore, the correlation between risk score and HRD was analyzed. There was a significant negative correlation between the two. Compared with the high-risk samples, the HRD score of the samples with low-risk type was significantly improved (Fig. 9G), indicating that low-risk samples may be more responsive to chemotherapy therapy. However, the five chemotherapy and targeted drugs did not show a difference in sensitivity between the two risk subtypes (Fig. 9H).

Fig. 9.

The role of risk score in predicting immunotherapy response and chemotherapy drug sensitivity. A: T cell inflamed GEP score of two risk types in the OC cohort of TCGA and Spearman correlation analysis between risk score and T cell inflamed GEP score. B: Th1/ IFN-γ ssGSEA score between two risk types in the OC cohort of TCGA and Spearman correlation analysis between the two variables. C: Differences in cytolytic activity between two risk types in TCGA's OC cohort and correlation of cytolytic activity with risk score. D: Differences in immune checkpoint gene expression between two risk types. E: The correlation between risk score and gene expression in immune checkpoint. F: The MDSC, CAF, TAM.M2, T cell exclusion, T cell dysfunction and TIDE scores of samples with low-risk type and high-risk type. G: HRD score difference between two risk types in the OC cohort of TCGA and Spearman correlation analysis between risk score and HRD. H: Differences in sensitivity of five chemotherapy drugs between two risk types.

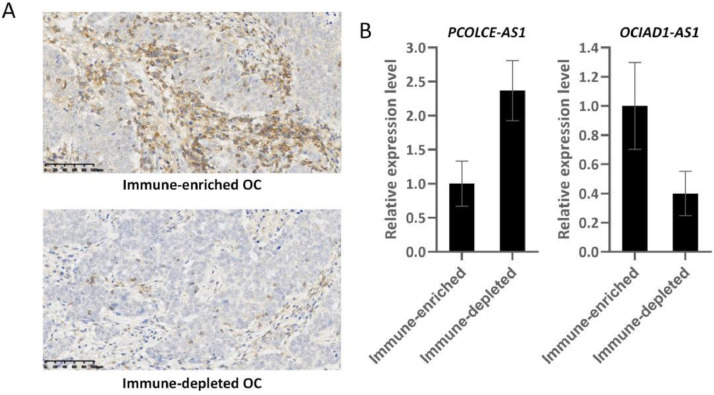

The expression of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 in immune-enriched and depleted oc tumors

The role of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 in OC has not been reported in histological studies. To investigate the effect of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 on the TME in OC, we performed IHC testing to examine the expression of CD45 in OC tumors. CD45 is a commonly-used immunohistochemical marker for white blood cells. CD45 deficiency in humans results in a severe immunodeficiency phenotype [35,36]. Therefore, the CD45-positive OC were defined as immune-enriched OC, whereas the CD45-negative tissues were defined as immune-depleted OC (Fig. 10A). PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 level were compared between immune-depleted OC and immune-enriched OC tissues. The level of PCOLCE-AS1 was noticeably elevated in immune-depleted OC tissue than in immune-enriched OC tissues, while OCIAD1-AS1 was remarkably elevated in immune-enriched OC tissues than in immune-depleted OC (Fig. 10B). These data indicated that PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 may be influential indicators of OC tumor immunity.

Fig. 10.

The expression of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 in immune-enriched and depleted OC tumors. A: Representative immunohistochemical staining for CD45 in OC tumors. B: PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 level between immune-enriched and depleted OC tissues, p<0.001.

Discussion

RNA modification participates in a variety of biological processes of immune cells in TIME, including in the development, differentiation, activation, migration and polarization, thereby regulating the immune response and participating in some immune-related diseases, including in cancers [37]. However, the interaction network between RNA modification and tumor immunity is still unclear to a large extent and requires further improvement. As RNA modification regulates the activity of lncRNAs in cancer, conversely, lncRNAs also regulates RNA methylation in cancers [38]. In this study, to establish a link between RNA modification and tumor immunity, we screened the lncRNAs associated with m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G and with immune molecules respectively, and selected lncRNAs related to both m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G and immune molecules for further exploring the effect of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNAs on OC.

By analyzing the unique categories and subclasses of TIME in patients' tumors, the ability to predict and guide immunotherapeutic responses could be improved, and new therapeutic targets will be revealed [39]. The OC classification based on immune-related lncRNAs [40] and the glioma prognostic model based on m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G related lncRNAs have been reported [41]. M6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related lncRNA has not yet been applied to explore the classification of OC. In this study, we screened 499 m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNAs, 19 of which showed significant prognostic value for OC and could divide OC into three subgroups. We not only focused on the prognosis of three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes, but also explored their genetic variation, TME components and therapeutic response. In terms of prognosis, there were significant differences among the three clusters, with C1 having the least favorable prognosis, followed by C2, and C3 with a better prognosis than C1 and C2. C3 with the optimal prognosis showed the highest levels of HRD score and SNV in comparison with C1 and C2, indicating that C3 had the lowest genomic stability. Genomic instability has been shown to be able lead to activate immune responses [42]. We found that unlike C 1 and C2, the main distribution in C3 was immunoreactive phenotype, and tha the immune-related indexes in TME such as immunescore, anti-tumor immune response steps, infiltrating immune cells and 29 Fges indicating global TME were highly enriched in C3, fully verifying the activation of immune response in C3.

Certain types of RNA modifications (m6A and m5C) participate in chemotherapy resistance and acquire therapeutic resistance to checkpoint inhibitors [43,44]. As the three OC subtypes in this study were produced by consensus clustering of m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA, they were likely to have different sensitivities to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. The results of analyzing the indicators related to ICB response confirmed that the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes had different responses to ICB treatment and different sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs, both of which were easier to implement in C3.

The analysis of the differential lncRNAs of the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes revealed a set of advanced lncRNA-based OC risk predictive system. A total of 507 DElncRNAs were identified among the three subtypes, 10 of which were selected as components of the risk scoring model. External validation results showed that this risk predictive system was an effective prognostic tool for OC. We also demonstrated that compared to the three immune-associated lncRNA signatures developed by previous study, the current risk predictive system achieved a relatively higher accuracy in predicting 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival of patients with OC, and its composition was relatively concise. Some lncRNAs in this set of risk predictive system have been reported to be related to tumor biology. At present, LINC00189 has only been found to be associated with recurrence-free survival of cervical cancer [45]. The carcinogenic effect of LINC00664 in oral squamous cell carcinoma is largely realized through regulating the miR-411–5p/KLF9 pathway [46]. In vitro cell experiments showed that LEMD1-AS1 plays an anti-tumor role in OC by targeting the miR-183–5p/TP53 axis [47]. GAS5 acts as a tumor suppressor in different tumor types, and its upregulation is involved in tumor sensitivity to chemotherapy or radiotherapy [48]. The expression of IFNG-AS1 is abnormally high in serum and tissue of patients with colon adenocarcinoma, which is related to TNM stage and poor prognosis of patients [49]. TYMSOS drives the adverse progression of gastric cancer through via molecular mechanism of ceRNA [50]. The expression of PCOLCE-AS1 was positively correlated with the survival rate of breast cancer patients [51]. The role of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 in OC has not been reported. This study explored the level of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 between immune-depleted OC and immune-enriched OC tissues. The level of PCOLCE-AS1 was significantly elevated in immune-depleted OC tissues than in immune-enriched OC tissues, while OCIAD1-AS1 was remarkably elevated in immune-enriched OC tissues than in immune-depleted OC, highlighting the potential of PCOLCE-AS1 and OCIAD1-AS1 serving as indicators to influence OC tumor immunity. The 10 lncRNAs were taken as a whole in this study to identify the TME characteristics, response to immunotherapy, and sensitivity to anticancer drugs of the OC population. We found that the high-risk group had significantly increased stromal score, M2 macrophage, CAFs, matrix, EMT, protumor cytokines, and greatly reduced number of M1 macrophage, macrophage and DC traffic, B cell, NK cell, T cell, effector traffic, MHCⅠ, tumor proliferation rate and significant inhibition of step 4, step 6, step 7 when compared to the low-risk group. Higher T cell imflamed GEP score [52], Th1/IFNγ ssGSEA score [27], and cytolytic activity [53] were all associated with better immunotherapy response, while CAF induced immunotherapy resistance [54]. Low-risk type samples showed significantly improved T cell inflamed GEP score, Th1/ IFNγ ssGSEA score, cytolytic activity, expression level of immune checkpoint molecules and downregulated CAF. Therefore, it was likely that the low-risk score responded better to immunotherapy, which also indicated that the risk predictive system we developed might be a potential tool for predicting OC response to immunotherapy.

To sum up, lncRNAs significantly correlated with m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G and with immune molecules were integrated, based on which three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G related immune lncRNA subtypes of OC were classified, showing differences in mutation pattern, TIME component and response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy.These findings provides a more detailed explanation for the heterogeneity of OC. The differential lncRNA analysis on the three m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related immune lncRNA subtypes revealed a set of risk predictive system for OC, which could reflect the prognosis and TME characteristics of OC populations with different clinical characteristics to some extent. Our results provided important insights into the co-regulation of RNA modification and immunity on the biology of OC, and might promote the development of therapeutic options for OC.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research Foundation of Guangzhou Women and Children's Medical Center for Clinical Doctor (2020RC003, 2021BS044, 2020BS028), the Guidance in Medical and Health Program of Xiamen, China (3502Z20224ZD1148), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (2023A04J1244), Plan on enhancing scientific research in GMU (02–410–2302169XM), and Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province (20201299).

Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Women and Children's Medical Center approved the current study (082B00), which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Prior to the inclusion into the study, all the patients provided informed consent for the utilization of their tissues and data.

Data availability statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kefei Gao: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Wenqin Lian: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rui Zhao: Writing – review & editing. Weiming Huang: Writing – review & editing. Jian Xiong: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Li Yuan and Zhongming Guo for their kindly assistance in sample collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101704.

Contributor Information

Weiming Huang, Email: huangweiming_fezx@yeah.net.

Jian Xiong, Email: 2022760187@gzhmu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Gupta K.K., Gupta V.K., Naumann R.W. Ovarian cancer: screening and future directions. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2019;29(1):195–200. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lheureux S., Braunstein M., Oza A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer: evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69(4):280–304. doi: 10.3322/caac.21559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A., Pius C., Nabeel M., Nair M., Vishwanatha J.K., Ahmad S., et al. Ovarian cancer: current status and strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med. 2019;8(16):7018–7031. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu T., Dai L.J., Wu S.Y., Xiao Y., Ma D., Jiang Y.Z., et al. Spatial architecture of the immune microenvironment orchestrates tumor immunity and therapeutic response. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021;14(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baci D., Bosi A., Gallazzi M., Rizzi M., Noonan D.M., Poggi A., et al. The ovarian cancer tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) as target for therapy: a focus on innate immunity cells as therapeutic effectors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(9) doi: 10.3390/ijms21093125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pansy K., Uhl B., Krstic J., Szmyra M., Fechter K., Santiso A., et al. Immune regulatory processes of the tumor microenvironment under malignant conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(24) doi: 10.3390/ijms222413311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teng P.C., Liang Y., Yarmishyn A.A., Hsiao Y.J., Lin T.Y., Lin T.W., et al. RNA modifications and epigenetics in modulation of lung cancer and pulmonary diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(19) doi: 10.3390/ijms221910592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rong D., Sun G., Wu F., Cheng Y., Sun G., Jiang W., et al. Epigenetics: roles and therapeutic implications of non-coding RNA modifications in human cancers. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2021;25:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou H., Rauch S., Dai Q., Cui X., Zhang Z., Nachtergaele S., et al. Evolution of a reverse transcriptase to map N(1)-methyladenosine in human messenger RNA. Nat. Methods. 2019;16(12):1281–1288. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0550-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J., Ding W., Xu Y., Tao E., Mo M., Xu W., et al. Long non-coding RNA RHPN1-AS1 promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis of ovarian cancer by acting as a ceRNA against miR-596 and upregulating LETM1. Aging. 2020;12(5):4558–4572. doi: 10.18632/aging.102911. (Albany NY) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S., Cao H., Ye L., Wen X., Wang S., Zheng W., et al. Cancer-associated methylated lncRNAs in patients with bladder cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019;11(6):3790–3800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkerson M.D., Hayes D.N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):1572–1573. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faison W.J., Rostovtsev A., Castro-Nallar E., Crandall K.A., Chumakov K., Simonyan V., et al. Whole genome single-nucleotide variation profile-based phylogenetic tree building methods for analysis of viral, bacterial and human genomes. Genomics. 2014;104(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomasini P., Greillier L. Targeted next-generation sequencing to assess tumor mutation burden: ready for prime-time in non-small cell lung cancer? Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(Suppl 4):S323–S3S6. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lv J., Zhu Y., Ji A., Zhang Q., Liao G. Mining TCGA database for tumor mutation burden and their clinical significance in bladder cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2020;40(4) doi: 10.1042/BSR20194337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mroz E.A., Tward A.D., Hammon R.J., Ren Y., Rocco J.W. Intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity and mortality in head and neck cancer: analysis of data from the cancer genome atlas. PLoS Med. 2015;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telli M.L., Timms K.M., Reid J., Hennessy B., Mills G.B., Jensen K.C., et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (hrd) score predicts response to platinum-containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3764–3773. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beroukhim R., Mermel C.H., Porter D., Wei G., Raychaudhuri S., Donovan J., et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463(7283):899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorsson V., Gibbs D.L., Brown S.D., Wolf D., Bortone D.S., Ou Yang T.H., et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2018;48(4):812–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshihara K., Shahmoradgoli M., Martinez E., Vegesna R., Kim H., Torres-Garcia W., et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman A.M., Liu C.L., Green M.R., Gentles A.J., Feng W., Xu Y., et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 2015;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen D.S., Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu L., Deng C., Pang B., Zhang X., Liu W., Liao G., et al. TIP: a Web Server for Resolving Tumor Immunophenotype Profiling. Cancer Res. 2018;78(23):6575–6580. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagaev A., Kotlov N., Nomie K., Svekolkin V., Gafurov A., Isaeva O., et al. Conserved pan-cancer microenvironment subtypes predict response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(6):845–865. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.014. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C.W., Shi W., et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auslander N., Zhang G., Lee J.S., Frederick D.T., Miao B., Moll T., et al. Robust prediction of response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in metastatic melanoma. Nat. Med. 2018;24(10):1545–1549. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dizier B., Callegaro A., Debois M., Dreno B., Hersey P., Gogas H.J., et al. A Th1/IFNgamma gene signature is prognostic in the adjuvant setting of resectable high-risk melanoma but not in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26(7):1725–1735. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erratum for the Research Article "Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy" by R. Cristescu, R. Mogg, M. Ayers, A. Albright, E. Murphy, J. Yearley, X. Sher, X. Q. Liu, H. Lu, M. Nebozhyn, C. Zhang, J. K. Lunceford, A. Joe, J. Cheng, A. L. Webber, N. Ibrahim, E. R. Plimack, P. A. Ott, T. Y. Seiwert, A. Ribas, T. K. McClanahan, J. E. Tomassini, A. Loboda, D. Kaufman. Science. 2019;363(6430). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Jiang P., Gu S., Pan D., Fu J., Sahu A., Hu X., et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018;24(10):1550–1558. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geeleher P., Cox N., Huang R.S. pRRophetic: an R package for prediction of clinical chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PLoS One. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng Y., Wang H., Huang Q., Wu J., Zhang M. A prognostic model based on immune-related long noncoding RNAs for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2022;15(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13048-021-00930-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abildgaard C., do Canto L.M., Rainho C.A., Marchi F.A., Calanca N., Waldstrom M., et al. The long non-coding RNA SNHG12 as a mediator of carboplatin resistance in ovarian cancer via epigenetic mechanisms. Cancers. 2022;14(7) doi: 10.3390/cancers14071664. (Basel) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun X., Li S., Lv X., Yan Y., Wei M., He M., et al. Immune-related long non-coding RNA constructs a prognostic signature of ovarian cancer. Biol. Proced. Online. 2021;23(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12575-021-00161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farolfi A., Gurioli G., Fugazzola P., Burgio S.L., Casanova C., Ravaglia G., et al. Immune system and DNA repair defects in ovarian cancer: implications for locoregional approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(10) doi: 10.3390/ijms20102569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kung C., Pingel J.T., Heikinheimo M., Klemola T., Varkila K., Yoo L.I., et al. Mutations in the tyrosine phosphatase CD45 gene in a child with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. Nat. Med. 2000;6(3):343–345. doi: 10.1038/73208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tchilian E.Z., Wallace D.L., Wells R.S., Flower D.R., Morgan G., Beverley P.C. A deletion in the gene encoding the CD45 antigen in a patient with SCID. J. Immunol. 2001;166(2):1308–1313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui L., Ma R., Cai J., Guo C., Chen Z., Yao L., et al. RNA modifications: importance in immune cell biology and related diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7(1):334. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi Y.C., Chen X.Y., Zhang J., Zhu J.S. Novel insights into the interplay between m(6)A modification and noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2020;19(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01233-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Binnewies M., Roberts E.W., Kersten K., Chan V., Fearon D.F., Merad M., et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018;24(5):541–550. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X., Gao J., Wang J., Chu J., You J., Jin Z. Identification of two molecular subtypes of dysregulated immune lncRNAs in ovarian cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021;246(5):547–559. doi: 10.1177/1535370220972024. (Maywood) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shao D., Li Y., Wu J., Zhang B., Xie S., Zheng X., et al. An m6A/m5C/m1A/m7G-related long non-coding rna signature to predict prognosis and immune features of glioma. Front. Genet. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.903117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen M., Linstra R., van Vugt M. Genomic instability, inflammatory signaling and response to cancer immunotherapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 2022;1877(1) doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shriwas O., Mohapatra P., Mohanty S., Dash R. The impact of m6A RNA modification in therapy resistance of cancer: implication in chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.612337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song H., Zhang J., Liu B., Xu J., Cai B., Yang H., et al. Biological roles of RNA m(5)C modification and its implications in Cancer immunotherapy. Biomark. Res. 2022;10(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40364-022-00362-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y., Zhang X., Zhu H., Liu Y., Cao J., Li D., et al. Identification of potential prognostic long non-coding RNA biomarkers for predicting recurrence in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020;12:719–730. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S231796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C., Wang Q., Weng Z. LINC00664/miR-411-5p/KLF9 feedback loop contributes to the human oral squamous cell carcinoma progression. Oral Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1111/odi.14033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo R., Qin Y. LEMD1-AS1 suppresses ovarian cancer progression through regulating miR-183-5p/TP53 axis. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:7387–7398. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S250850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambrou G.I., Hatziagapiou K., Zaravinos A. The non-coding RNA GAS5 and its role in tumor therapy-induced resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(20) doi: 10.3390/ijms21207633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z., Cao Z., Wang Z. Significance of long non-coding RNA IFNG-AS1 in the progression and clinical prognosis in colon adenocarcinoma. Bioengineered. 2021;12(2):11342–11350. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.2003944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu Y., Wan C., Zhou G., Zhu J., Shi Z., Zhuang Z. TYMSOS drives the proliferation, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells by regulating ZNF703 via sponging miR-4739. Cell Biol. Int. 2021;45(8):1710–1719. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X., Gao S., Li Z., Wang W., Liu G. Identification and analysis of estrogen receptor alpha promoting tamoxifen resistance-related lncRNAs. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/9031723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haddad R.I., Seiwert T.Y., Chow L.Q.M., Gupta S., Weiss J., Gluck I., et al. Influence of tumor mutational burden, inflammatory gene expression profile, and PD-L1 expression on response to pembrolizumab in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2022;10(2) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rooney M.S., Shukla S.A., Wu C.J., Getz G., Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kieffer Y., Hocine H.R., Gentric G., Pelon F., Bernard C., Bourachot B., et al. Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast clusters linked to immunotherapy resistance in cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(9):1330–1351. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.