Abstract

Neologisms refer to newly coined words or phrases adopted by a language, and it is a slow but ongoing process that occurs in all languages. Sometimes, rarely used or obsolete words are also considered neologisms. Certain events, such as wars, the emergence of new diseases, or advancements like computers and the internet, can trigger the creation of new words or neologisms. The COVID-19 pandemic is one such event that has rapidly led to an explosion of neologisms in the context of the disease and several other social contexts. Even the term COVID-19 itself is a newly coined term. Studying such adaptation or change and quantifying it is essential from a linguistic perspective. However, identifying newly coined terms or extracting neologisms computationally is a challenging task. The standard tools and techniques for finding newly coined terms in English-like languages may not be suitable for Bengali and other Indic languages. This study aims to use a semi-automated approach to investigate the emergence or modification of new words in the Bengali language amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. To conduct this study, a Bengali web corpus was compiled consisting of COVID-19 related articles sourced from various web sources in Bengali. The current experiment focuses solely on COVID-19-related neologisms, but the method can be adapted for general purposes and extended to other languages as well.

Keywords: Neologisms, COVID-19, Linguistic analysis, Word formation, Corpus, Bengali, Language.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on human life globally. It resulted in a high number of casualties and presented unprecedented challenges to various systems such as healthcare, food systems, and the world of work [1]. It has also affected language, as observed by the Oxford English Dictionary, which has taken special attention to documenting the impact of the pandemic on the English language [2]. Throughout history, epidemics and pandemics have contributed significantly to neologisms, and the COVID-19 pandemic has continued this tradition [3]. It is a common phenomenon for languages to undergo changes over time, and one such change during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the rapid emergence of new terminologies. From a linguistic perspective, researchers aim to analyze the new terminologies that have been coined or adopted during the pandemic, to study their meanings and how they affect human social life. This is important because the meaning of individual tokens or certain phrases can shift in the context of language use [4].

Lexicographers typically gather these new English words from various sources such as books, articles, social media, and news, and promptly update language resources, including dictionaries. However, the computational challenge lies in automating the process of identifying newly coined terms from various discourses. Web sources have become the primary resource for discourse or corpora. Conventional tools and techniques, such as the Sketch Engine tool [5], are available for English-like European languages. These are useful for text analysis and mining applications and beneficial for linguists, lexicographers, and translators. Due to the linguistic complexity, these tools are not adaptable to Indic languages like Bengali. Therefore, this paper aims to present a semi-automated technique to find neologisms in Bengali.

Languages can change for various reasons, including technological advancements and adaptations to changes in social systems [6]. For instance, with the popularization of computers among the common people, several new terms (e-mail, bug, click, cursor, mouse,...) were coined that were not in use prior to the advent of computers. Similarly, the term selfie became popularized after the widespread use of smartphones [7].

Literature Review

Previously, neologisms were identified through manual analysis of literature, newspapers, technical and scientific texts, but this process was time-consuming and tedious [8, 9]. The main objective of the task was to extract collocations [10] and identify relationships [11] for the purpose of analysis. However, the introduction of digital technology has transformed linguistic and NLP research, resulting in the development of new data collection methods and tools [12, 13]. Nowadays, a range of automated techniques and tools are available that can scan numerous texts, especially newspapers, to automatically detect newly created words in different languages [14–18]. In this section, we will offer a succinct summary of some of the most notable contributions within this particular area.

The corpus is a frequently utilized resource in the study of neologisms, and researchers commonly employ various methods such as the web-as-corpus approach [19, 20], news corpora [21], and the English edition of Wikipedia [22]. It should be noted that although web sources offer a considerable amount of information for the study of neologisms, they also pose certain challenges, including the presence of noisy data, informal language, and misspellings. Hence, researchers must utilize different preprocessing techniques and tools to cleanse and filter the data prior to analysis. Paryzek [23] examines various methods of extraction for retrieving neologisms. Meanwhile, Grieve et al. [24] shed light on the factors that contribute to the emergence and popularity of neologisms. In their study, Schmid et al. [25] incorporated corpora from social media platforms. There are several agencies [26, 27] who have compiled scientific literature on COVID-19 are sometimes termed as corpus. A study on the linguistic aspects of the English language was conducted by Alyeksyeyeva et al. [28], which identified various jargon, slang, and other terms related to COVID-19 that have been adopted in culture.

Numerous studies have been conducted and are ongoing during the COVID-19 pandemic period, including research on neologisms related to the coronavirus. Akut [29] conducted a morphological analysis of these newly coined terms and categorized them grammatically, noting that the majority were nouns and verbs. Khalfan et al. [30] explored COVID-19 neologisms from a linguistic perspective and attempted to establish a language-mind relationship. Katermina et al. [31] studied the reflection of COVID-19 neologisms in the medical domain, as well as various social phenomena aspects. Estabraq et al. [32] focused on neologisms in social media, analyzing three million tweets collected from January to May 2020. They also provided a list of COVID-19 expressions, their contexts, and lexical deviations. Falk et al. [33] employed a machine learning approach based on support vector machines (SVM) to detect neologisms in a corpus of French RSS feeds sourced from newspapers. They utilized three types of morpho-syntactic features, specifically related, morpho-lexical, and thematic features, to aid in their detection process.

Apart from the above, there are numerous online resources that update the newly coined terms and their information at regular intervals with their interpretation. Notably, some of the most distinguished resources comprise About words by Cambridge University Press,1 New Words by Merriam-Webster,2 New Words by Oxford English Dictionary,3 WordSpy: Dictionary of New Words,4 etc. The CORD-19 dataset, also known as the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset [34], is an expanding repository that receives daily updates from multiple sources. The Canadian government has recently published a glossary specifically related to the pandemic [35].

The lack of research on neologisms associated with COVID-19 in Indic languages has been noted in prior literature. Senapati et al. [36] made an effort to look into it for Bengali languages by employing rudimentary methods like the set difference operation. Moreover, the present methods and tools for examining neologisms are not easily transferable to Bengali or other Indic languages. These circumstances have inspired our inquiry into COVID-19 neologisms specifically in Bengali.

Experimental Setup

This system is designed to focus on newly created words related to COVID-19 in Bengali. It assumes that these words did not exist before the virus was first identified. To ensure that all COVID-19 neologisms are included, a specific Bengali corpus dedicated to COVID-19 is required. Initially, a specialized Bengali web-corpus for COVID-19 is created to serve as a resource for neologisms, which is subsequently utilized in the neologism detection process. The experimental setup involves three phases: developing the COVID-19 online corpus, applying the neologism identification algorithm, and conducting tests.

System Description

Our system is based on the following three assumptions:

No Bengali text prior to the virus was first identified, containing any newly coined term related to COVID-19. Since, the end of January 2020, WHO declared coronavirus as a public health emergency of international concern5 and the first news article related to COVID-19 has published on January 2020, in Anandabazar Patrika6 hence considered the start date of the pandemic January 2020.

Define a Reference dictionary, Lexicon: Ideally, this dictionary, lexicon should contain all Bengali terms except the COVID-19 related neologism. In the implementation, it consists of the TDIL Bengali corpus along with the Bengali Anandabazar Lexicon.7 The TDIL corpus is made up of 3,34,260 sentences and 44,29,574 words in 1,362 files. The Bengali Anandabazar Lexicon, on the other hand, contains 5,45,899 distinct words.

The terms found in an online Bengali dictionary are not newly coined terms. In the implementation Samsad8 online Bangla dictionary is used. Even though the dictionary had been updated in June 2020, it is tested that the COVID-19-related vocabulary had not been added (accessed on 09-03-2023).

Resources Used for the System

Our system’s primary resource is a Reference dictionary that is expected to encompass all Bengali terms, but in reality, it is based on various sources such as the TDIL Bengali corpus [37], news lexicon from Anandabazar Patrika, and randomly selected Bengali text from the web, including Bengali Wikipedia (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic). This dictionary comprises a vast collection of 4,43,260 sentences and 56,29,753 words along with 5,45,899 distinct words from the Anandabazar lexicon. Additionally, the system utilizes an online Bengali dictionary, Samsad,9 to cross-check if any word is present in the dictionary.

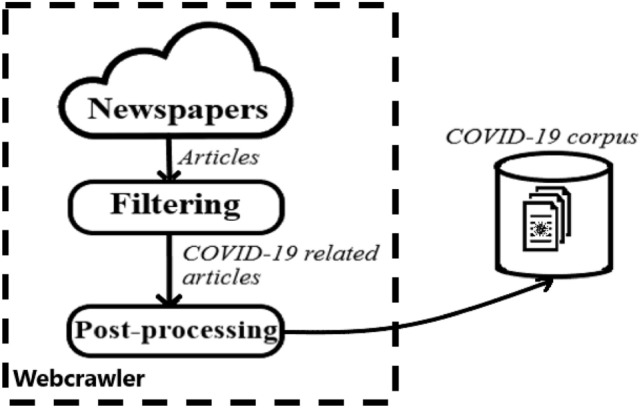

The source of the data used to retrieve neologisms is the Web-as-Corpus [38]. However, the existing crawlers10 are not suitable for accessing the Web-as-Corpus. Hence, we developed a custom web crawler using the Python library BeautifulSoup to retrieve links to news articles and extract text from them. To differentiate COVID-19-related articles from non-COVID-19-related ones, a set of keywords related to COVID-19 is required. These terms, such as corona, covid, virus,... are explicitly collected from COVID-19-related articles.

The web corpus that is obtained requires cleaning to eliminate jargon and unwanted materials. It has been observed that news articles may be linked multiple times on different dates or may be referenced through links on other pages, resulting in duplicated text in the corpus. This can reduce the quality of the corpus and create misleading descriptive statistics. To address this issue, a set data structure is utilized to store links, ensuring that each element is only included once, even if it appears multiple times. The news text may contain various elements such as images, image captions, English words, multilingual text, and numerals, which must be removed. This is typically achieved by filtering out HTML tags and English alphabets. Finally, the cleaned data is saved in a text file in Unicode format, along with the news URLs, including the news headline, publishing date, editor’s name, and news text. The block diagram of the corpus creation system is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

System of the corpus creation from the web

The COVID-19 Corpus

Since the system is focused solely on COVID-19 neologisms, the targeted dataset should ideally include all terms related to COVID-19. Since the beginning of 2020, the topic of COVID-19 has been widely discussed, with newspapers prioritizing coverage of related issues. The best collection of COVID-19 neologisms may be the articles related to COVID-19 that have been collected from the beginning of the pandemic until they became relevant to health issues. The intended dataset for COVID-19 neologisms is online news articles, along with other COVID-19 related articles. At the beginning of 2020, COVID-19 has been a widely discussed topic, and newspapers have given it priority coverage. Even today, COVID-19 / Adenoviruses [39] continues to be a current and relevant topic. As the first news article related to COVID-19 was published on January 23, 2020, in Anandabazar Patrika, we have selected the period from January 1, 2020, to January 28, 2022, for our corpus (Web-as-Corpus).

Our COVID-19 corpus comprises news articles related to COVID-19 published between January 1, 2020, and January 28, 2022, which is a span of 759 days. However, as we have only been able to obtain news articles since January 23, 2020, our corpus contains news articles published during 737 days, starting from January 23, 2020. It’s worth noting that all news articles published on a particular day are stored in a single file, resulting in a total of 737 files for our corpus, covering the time period from January 23, 2020, to January 28, 2022. A summary of the COVID-19 corpus’s size is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The size of the COVID-19 news database

| Sl No | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of files | 737 |

| 2 | Number of news articles | 16,637 |

| 3 | Number of Sentences | 3,49,392 |

| 4 | Number of words | 45,42,113 |

| 5 | Disk space | 85 MB |

Algorithm for the Neologism Detection

The system’s algorithm is presented in the flowchart shown in Fig. 2. This algorithm relies on three assumptions outlined in Section “System Description” and utilizes two key resources: the Lexicon and Dictionary, depicted in Fig. 2, which are described in Section “Resources Used for the System”.

Fig. 2.

System flowchart: execution flow

An additional prepossessing step is performed prior to execution, which is not depicted in Fig. 2. Firstly, the COVID-19 corpus is represented using a set data structure to eliminate redundancy and repetition. This is achieved by storing each element in the set data structure, as the intrinsic property of a set ensures that each element is only stored once, thereby eliminating redundancy and repetition. Next, the FIRE stop word11 and Kaggle stop word12 lists are used to remove stop words from the corpus. The system generates neologisms for words that are not found in the existing lexicon or online dictionary. Once the neologism list is generated, a manual post-processing step is performed to finalize the list.

Results and Discussion

As the verification of the result required human expertise, we were only able to check the system output that had been identified as a neologism. Therefore, we have only reviewed the cases that were classified as true positive and false positive, without being able to examine any false negatives.

Overall, the system detected 7847 neologisms, but upon manual inspection, only 1564 were confirmed to be true. The corpus indicates the presence of 1564 neologisms related to COVID-19. While this figure may seem high, upon closer examination, we have noticed that only 185 of these neologisms were genuine, with the remaining consisting of derivative or inflected forms of those 185 neologisms.

Furthermore, we have computed both the frequency and ranking of the neologisms that were identified. The ranking is based on their frequency in descending order. Neologisms with higher ranks are presented in Fig. 3, while Fig. 4 illustrates neologisms with lower ranks or less frequency. According to the rank list, CORONA and its various forms are the most commonly used words.

Fig. 3.

Frequency wise rank list of COVID-19 related newly added terms in Bengali

Fig. 4.

Lowest frequency wise rank list of COVID-19 related newly added terms in Bengali

Some neologisms with the lowest frequency are displayed in Fig. 4. It’s worth noting that the term "NEOCOV," ranked at 105, was reported in the newspaper13 on January 2022, and is included in our findings.

An analysis reveals that there are 213 derived terms from the newly coined term corona, 81 derived terms from covid, and so on. Figure 5 displays some examples of these derived or inflected forms.

Fig. 5.

Derived neologisms

The newly coined term is created by utilizing different word-formation techniques. Liu et al. [40] identify a range of methods for creating words, including prefixation, suffixation, acronym formation, blending, borrowing, compounding, and more. Many of the newly coined terms fall under one of these categories. Examples of word formation rules, along with corresponding examples, are illustrated in Fig. 6. Furthermore, we have also included some previously existing words with updated meanings.

Fig. 6.

Word-formation rules

Error Analysis

As previously mentioned, our analysis has solely focused on the neologisms identified by our system, which includes both the true positive and false positive cases. As it has identified a total of 7847 neologisms, including 185 true neologisms and 1379 (1564–185) derived forms, an error analysis has been performed to identify weaknesses in the system. The analysis presented here is based on the 6283 (7847–1564) false cases, and the errors have been classified into two main categories: lexical errors and semantic errors. It’s worth noting that we have not analyzed each of the 6283 cases individually, but rather analyzed the major classes of the error. Lexical errors include spelling mistakes, erroneous characters added to words, and words combined with others. On the other hand, semantic errors consist of valid words that are not neologisms, such as names of people, locations, or medicines. The first category has 4603 errors, while the second category has 1680 errors. Figure 7 displays examples of these categories, and Fig. 8 shows a pie chart representing the results along with the error classification.

Fig. 7.

Error classification

Fig. 8.

System identified neologism and errors

Several observations have been made in different phases of the system. It was discovered that the word korona or corona (which was ranked as the top neologism in Fig. 3) already exists in the Bengali lexicon (in the Anandabazar lexicon), but with a different meaning (as shown in Fig. 6). The previous usage of the term korona (Corona) referred to the total solar eclipse, during which the Sun appeared as a black disc with white milky radiation around it, known as the korona (Corona). However, today, "korona" (Corona) is generally interpreted as the coronavirus. That is why, the system failed to recognize corona as a new word, but it did detect its related terms. As a result, we manually included it in the system. The term koarantin or quarantine (ranked 3 in Fig. 3) appears as a neologism in the Bengali novel "Srikanto" (Part Two) written by Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay.14 The context in the novel was the precautions taken during the pandemic disease plague in Burma. However, the term was not commonly used and had become obsolete. Its resurgence occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it has since re-entered the Bengali lexicon.

Conclusion

This paper makes a valuable contribution in multiple aspects. Not only does it pioneer the creation of Bengali neologisms, but it also documents and provides linguistic resources of great value. The paper’s contributions can be summarized briefly as follows:

Firstly, a specific COVID-19 Bengali news corpus has been developed. Secondly, a semi-automated approach to extracting the COVID-19 corpus has been suggested, which can be applied to any language. The system’s results have been thoroughly investigated and documented, yielding a list of 185 true and 1379 derived COVID-19 neologisms. The derived neologisms have been analyzed based on their formation rules.

Additionally, an error analysis has been conducted to identify the major sources of errors. The fine-grained analysis of the errors, features, results, and word formation methods will pave the way for better performance and explore new directions.

Overall, the COVID-19 corpus and the list of neologisms constitute valuable linguistic resources that will greatly aid further research in the domain of linguistic and language processing research.

Author Contributions

I (AS) am the sole contributor to the paper.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Data are taken from the online newspaper Anandabazar Patrika (https://www.anandabazar.com/). Data is automatically collected (web scraping) and saved in text files for research work.

Code Availability

Developed my code. For the web crawler use the python library beautifulsoup and save the web text in the text files. For the implementation and analysis developed the necessary java code. The entire code base is with me.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author Apurbalal Senapati declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or animals

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

I (Apurbalal Senapati), transfer my consent for the publication of identifiable details, which can include photographs and details within the text to be published in the above Journal and Article.

Ethics Approval

I (Apurbalal Senapati) declared that the manuscript has not been submitted or published anywhere. I also, give the assurance that I will not be submitted this manuscript elsewhere until the editorial process is completed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Still S. COVID-19 health system response, quarterly of the European observatory on health systems and policies. Eurohealth. 2020;26(2):108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McPherson F, Stewart P, Wild K. Presentation on “The language of Covid-19: special OED update”, OED. 2020. https://public.oed.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Language-of-Covid-19-webinar_10-09-20_presentations.pdf. Accessed 12 June 2021.

- 3.Asif M, Zhiyong D, Iram A, Nisar M. Linguistic analysis of neologism related to coronavirus (COVID-19). 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3608585. Accessed 17 June 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Luke S. Language evolution, acquisition, adaptation and change, sociolinguistics—interdisciplinary perspectives. In: Jiang X. editor. IntechOpen; 2017. 10.5772/67767, https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/54552. Accessed 17 June 2022.

- 5.Kilgarriff A, Baisa V, Bušta J, et al. The Sketch Engine: ten years on. Lexicogr ASIALEX. 2014;1:7–36. doi: 10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harya TD. Language change and development: Historical linguistics. Premise J Eng Educ. 2016;5(1):103–117. doi: 10.24127/pj.v5i1.418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youngsoo S, Minji K, Chaerin I, Sang CC. Selfie and self: The effect of selfies on self-esteem and social sensitivity. Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;111:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruth O, Mary O. A Systematic approach to the selection of neologisms for inclusion in a large monolingual dictionary. In: Proceedings of the 13th EURALEX International Congress, 2008; pp. 571–79.

- 9.Frank AS. From n-grams to collocations: an evaluation of Xtract. In: The Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, 1991; pp. 279-284.

- 10.Frank AS. From n-grams to collocations: an evaluation of Xtract. In: Proceedings of the 29th annual meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, 1991; pp. 279–84, Association for Computational Linguistics.

- 11.Douglas B. Squibs and discussions co-occurrence patterns among collocations: a tool for corpus-based lexical knowledge acquisition. Comput Linguist. 1993;19(3):531–538. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mejri S, Sablayrolles JF. Présentation: Néologie, nouveaux modèles théoriques et NTIC. Langages. 2011;183:3–9. doi: 10.3917/lang.183.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humbley J, Sablayrolles JF. Néologie et corpus. No. 10 in Neologica. Revue internationale de néologie. 2016.

- 14.Kerremans D, Stegmayr S, Schmid HJ. The NeoCrawler: identifying and retrieving neologisms from the internet and monitoring ongoing change. In: Allan K, Robinson J, editors. Current methods in historical semantics. De Gruyter: Mouton; 2012. pp. 59–96. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingrid F, Delphine B, Christophe G. From non word to new word: automatically identifying neologisms in French newspapers. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC’14), 2014; pp. 4337–344, http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2014/pdf/288_Paper.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

- 16.Maarten J. NeoTag: a POS Tagger for Grammatical Neologism Detection. In: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC’12), 2012; pp. 2118–124. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2012/pdf/1098_Paper.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

- 17.Paul R, Roger G. Comparing corpora using frequency profiling. In: Proceedings of the Workshop on Computer Corpora, 2000; pp. 1–6.

- 18.Ted D. Accurate methods for the statistics of surprise and coincidence. Comput Linguist. 1993;19(1):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laurie B, Antoinette R. Contextual clues to word-meaning. Int J Corpus Linguisti. 2000;5:231–258. doi: 10.1075/ijcl.5.2.07ren. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hohenhaus P. Bouncebackability. A webas-corpus-based study of a new formation, its interpretation, generalization/spread and subsequent decline. SKASE J Theoret Linguist. 2006;3:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renouf A. Tracing lexical productivity and creativity in the British Media: The Chavs and the Chav-Nots. In: Lexical creativity, texts and contexts; 2007, p. 61–92. 10.1075/sfsl.58.12ren

- 22.Tony V, Cristina B. Harvesting and understanding on-line neologisms. In: Cognitive perspectives on word formation; 2010, pp. 399–418.

- 23.Piotr P. Comparison of selected methods for the retrieval of neologisms. Investig Linguisicae. 2008;16:163–181. doi: 10.14746/il.2008.16.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jack G, Andrea N, Diansheng G. Analyzing lexical emergence in Modern American English online. In: english language and linguistics. 2016.

- 25.Daphne K, Susanne S, HansJ S. The Neocrawler: identifying and retrieving neologisms from the internet and monitoring ongoing change. In: Allan K, Robinson JA, editors. Current methods in historical semantics. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton; 2012. pp. 59–96. [Google Scholar]

- 26.A comprehensive knowledgebase for coronaviruses. https://covid-19base.hbku.edu.qa/Gene/ACE2/d=Covid-19. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

- 27.Chen LC, Chang KH, Chung HY. A novel statistic-based corpus machine processing approach to refine a big textual data: an ESP Case of COVID-19 news reports. Appl Sci. 2020;2020(10):5505. doi: 10.3390/app10165505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AlyeksyeyevaIryna I, ChaiukTetyana A, Galitska CA. Coronaspeak as key to coronaculture: studying new cultural practices through neologisms. Int J Eng Linguist. 2020;10(6):202–212. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v10n6p202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katherine BA. Morphological analysis of the neologisms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Eng Lang Stud (IJELS) 2020;15:10. doi: 10.32996/ijels.2020.2.3.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalfan M, Batool H, Shehzad W. Covid-19 neologisms and their social use: an analysis from the perspective of linguistic relativism. Linguist Lit Rev. 2020;6(2):117–129. doi: 10.32350/llr.62.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katermina VV, Lipiridi SC. Reflection on the social and psychological consequences of the coronavirus pandemic in the new vocabulary of the non-professional English language medical discourse. In: Proceedings of the Research Technologies of Pandemic Coronavirus Impact (RTCOV 2020), 2020; pp. 44–49. 10.2991/assehr.k.201105.009 (ISSN: 2352-5398, ISBN: 978-94-6239-268-7).

- 32.Estabraq RI, Suzanne AK, Hussain HM, Haneen AH. A sociolinguistic approach to linguistic changes since the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Multicult Educ. 2020 doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4262696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falk I. From non word to new word: automatically identifying neologisms in French newspapers. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on language resources and evaluation, 2014); pp. 4337-4344. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2014/pdf/288_Paper.pdf.

- 34.Lu Wang L, Lo K, Chandrasekhar Y, Reas R, Yang J, Eide D, Funk K, Kinney R, Liu Z, Merrill W, Mooney P, Murdick D, Rishi D, Sheehan J, Shen Z, Stilson B, Wade AD, Wang K, Wilhelm C, Xie B, Raymond D, Weld DS, Etzioni O, Kohlmeier S. CORD-19: The Covid-19 Open Research Dataset. (2020) ArXiv [Preprint]. 2020. arXiv:2004.10706v2. (PMID: 32510522; PMCID: PMC7251955).

- 35.Translation B. Glossary on the COVID-19 pandemic. 2021. https://www.btb.termiumplus.gc.ca/publications/covid19-eng.html#a. Accessed 17 June 2022.

- 36.Senapati A, Nag A. Neologism related to COVID-19 pandemic: a corpus-based study for the Bengali language. In: Bhateja V, Tang J, Satapathy SC, Peer P, Das R, editors. Evolution in computational intelligence. Smart innovation, systems and technologies. Singapore: Springer; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 37.TDIL Corpus. A nation-wide consortium for machine translation of Indic languages is being funded by the Ministry of Information Technology, Govt. of India; 1995. http://www.tdil-dc.in. Accessed 17 June 2022.

- 38.Adam K, Gregory G. Introduction to the special issue on the web as corpus. Comput Linguist. 2003;29(3):333–347. doi: 10.1162/089120103322711569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News; Multi-country—acute, severe hepatitis of unknown origin in children. 2022. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON376.

- 40.Liu W, Liu W. Analysis on the word-formation of English netspeak neologism. J Arts Hum. 2014;3(12):22–30. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are taken from the online newspaper Anandabazar Patrika (https://www.anandabazar.com/). Data is automatically collected (web scraping) and saved in text files for research work.

Developed my code. For the web crawler use the python library beautifulsoup and save the web text in the text files. For the implementation and analysis developed the necessary java code. The entire code base is with me.