Abstract

Nucleic acid testing (NAT) is used to screen transfusiontransmittable infections (TTIs) in donated blood samples and provide an additional layer of blood safety. In this study, we describe our experience in screening viral TTIs using two formats of NAT: cobas® MPX2 polymerase chain reaction- based minipool NAT (PCR MP-NAT) and Procleix Utrio Plus transcription-mediated amplificationbased individual donor-NAT (TMA ID-NAT). Data routinely collected as a part of blood bank operations were retrospectively analysed over a period of 70 months for TTIs. Blood samples were initially screened for HIV, HBV, HCV, syphillis by chemiluminescence and malaria by Rapid card test. In addition to serological testing, all samples were further screened by TMA-based ID-NAT (ProcleixUltrio Plus Assay) during Jan 2015–Dec 2016, and by PCR-based MP-NAT (Cobas® TaqScreen MPX2) during Jan 2017–Oct 2020. RESULTS: A total of 48,151 donations were processed over 70 months, of which 16,212 donations were screened by ProcleixUtrio Plus TMA ID-NAT and 31,939 donations by cobas® MPX2 PCR MP-NAT. Replacement donors and male donors outnumbered voluntary donors and female donors respectively. The overall NAT yield rate of MP-NAT was 1:2281 compared to 1:3242 with ID-NAT, during the respective time period. ID-NAT detected 5 HBV infections missed by serology, whereas MP-NAT detected 13 HBV infections and 1 HCV infection missed by serology. The proportion of donations that were both seroreactive and NAT reactive was higher with MP-NAT (59.8%) compared to ID-NAT (34.6%). Cobas® MPX2MP-NAT had higher overall NAT yield rate compared to ProcleixUtrio Plus ID-NAT and confirmed a higher proportion of seroreactive donations. Due to the ease of operation, simple algorithm, cobas® MPX2 PCR based MP-NAT can be an effective solution for blood screening in India.

Keywords: NAT, Minipool, Transfusion, Transmitted infection

Introduction

According to the recent estimates, the sero-prevalence of the three ‘H’ viral transfusion-transmittable infections (TTIs) among blood donors in India ranges between 2–8% for HBV (hepatitis B virus), 0.5–1.5% for HCV (hepatitis C virus), and 0.16-0.30% for HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) [1]. Though the Government of India has mandated serological screening of these viral TTIs, additional nucleic acid testing (NAT) for these infections could improve sensitivity of screening and overall blood safety. NAT is a molecular technique which detects the viral DNA/RNA in the donor blood samples and helps reduce TTIs thus providing an additional layer of blood safety. NAT was introduced in the late 1990s for blood screening [2], and many developed countries have mandated NAT in blood screening along with serology [3].

In contrast to serological tests which detect the host immune response, NAT detects the presence of viral genetic material. Therefore, when NAT is used in addition to serological testing, it is possible to considerably shorten the window period of TTI detection in donated samples. Furthermore, NAT can also detect mutants and occult infections which are often missed by serological tests [4]. All these factors contribute to improving blood safety. The need for NAT depends on the prevalence and incidence rate of TTIs in the blood donor population, available resources, and evidence of benefit added when combined with serology tests. Hence, the decision to start NAT should be considered alongwith a quality-assured blood transfusion system, such as a volunteer base for blood donation, the provision of donor self-deferral, donor notification and counselling along with sensitive, quality-assured serological methods for testing TTIs.

NAT could be based on any of the two technologies—polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or transcription-mediated amplification (TMA); it could be performed by any of the two methods—individual donor (ID-NAT) and minipool (MP-NAT) [2]. Our blood bank adopted ProcleixUltrio-Plus TMA based ID-NAT from January 2013 to 2016, and we shifted over to cobas® MPX2 PCR based MP-NAT from January 2017. This placed us in a unique position to perform a first-hand comparison of the TTI detection rates of the two NAT methods over a cumulative period of nearly 6 years, and this study presents the results of this comparison.

Methodology

Study Setting, Study Participants

This retrospective, single-centre, observational study was carried out in the blood bank maintained by the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute, New Delhi. All donations collected during 1st January 2015 to 27th October 2020 were included in the present study. As part of the routine blood donation process, all donors (voluntary and replacement) were initially screened through a detailed history and physical examination, and blood was collected following applicable regulatory guidelines issued by the competent authority [5].

Serological Testing

After blood collection, all donations were serologically tested to detect viral TTIs by identifying the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-HCV, anti-HIV-1, and anti-HIV-2 antibodies through chemiluminescence (VITROS® ECi Immunodiagnostic Systems, Ortho Clinical Diagnostics). In addition, the donations were also tested for antibodies against syphilis (TPHA test through chemiluminescence, VITROS® ECi Immunodiagnostic Systems, Ortho Clinical Diagnostics) and malarial antigens (Pl falciparum and Pl. vivax through rapid card test, Care Start TM Malaria). All the tests were carried out as per manufacturer’s specifications, and all seroreactive donations were discarded, regardless of NAT results, without performing any additional tests.

Molecular Screening

In addition to the above serological testing, all the donations were tested for the presence of viral genetic material through NAT. From January 2015 to December 2016, ID-NAT was performed on individual donated samples using the ProcleixUltrio Plus Assay (Novartis Emeryville, CA), which was based on TMA [6, 7]. Subsequently, from January 2017, MP-NAT on minipools of 6 samples was performed using Roche cobas®TaqScreen MPX test v2.0 (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) on the cobas® 201 system (Roche Instrument Center, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), which is a fully automated assay based on PCR.

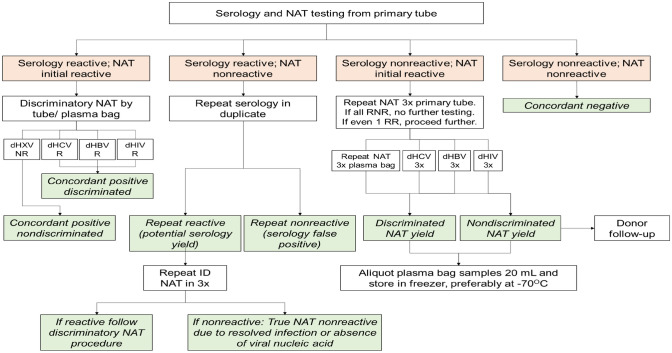

For the TMA-based ID-NAT, target amplification was done by transcription-based nucleic acid amplification method on a semi-automated platform. Detection was achieved by hybridization protection assay (HPA) using single-stranded nucleic acid probes with chemiluminescent labels that are complementary to the amplicon [6, 7]. For initial screening, individual donations in primary tube were run in triplicates. Non-Repeat reactive donations were considered as false positives. Initial reactive donations were further screened in triplicates in plasma bag. The reactive individual donations were then further discriminated in triplicates each for HBV, HCV, and HIV respectively (Fig. 1) [8]. Ultrio Plus Assay detects HIV-1 group M (subtypes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H), group N, and group O genetic variants; genotypes 1 to 6 of HCV, and genotypes A to G of HBV [6, 7].

Fig. 1.

Workflow algorithm for TTI screening using ID-NAT based on TMA that was followed in the present study. Adapted from [8]. Note NAT nucleic acid testing; dHXV discriminatory HCV/ HBV/ HIV; dHCV discriminatory HCV; dHBV discriminatory HBV; dHIV discriminatory HIV; NR nonreactive; R reactive; ID individual donor; RNR repeat nonreactive; RR repeat reactive; 3 × tested in triplicate

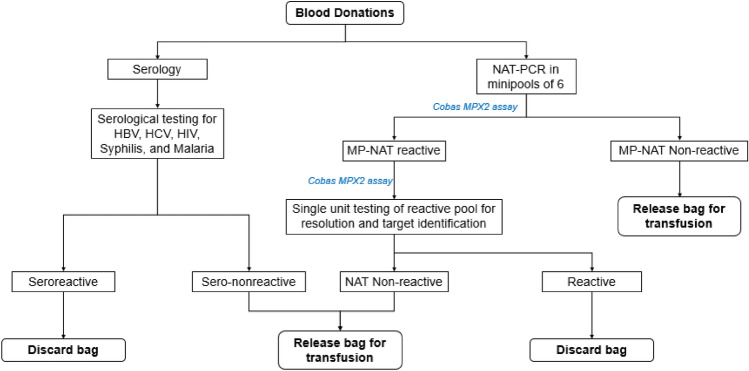

For the PCR-based MP-NAT, all donations were initially screened by Cobas® Taxscreen MPX test v2.0 in minipools of 6, and non-Reactive donations were released. Reactive pools were resolved, and individual donations were subject to repeat testing using the same Cobas® Taxscreen MPX test v2.0. (Fig. 2) [8]. The Cobas® TaqScreen MPX test v2.0 detects HIV-1 group M (subtypes A, AE, AG, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, B/D, and G/BG), group N, group O, and HIV-2 (subtypes A, A/B, B); genotypes 1a, 1b, 2, 2a, 2a/c, 2b, 3a, 3a/b, 4, 4a, 4b/c, 4c, 4d, 4acd, 4p, 4q, 4 h, 5, 5a, 6, 6a, 6a/b, and 6c of HCV; and genotypes A to H of HBV [9].

Fig. 2.

Workflow algorithm for TTI screening using MP-NAT based on PCR that was followed in the present study.Manufacturer's protocol recommends NAT screening for only sero-nonreactive samples; in our centre, all samples were screened by both serology and NAT to maintain uniformity. Note NAT nucleic acid testing; PCR polymerase chain reaction; MP minipool

calculating NAT yield, all NAT reactive donations were considered, and all sero-nonreactive donations showing NAT reactivity were considered NAT yield.

Samples which were seroreactive and/or NAT reactive, regardless of concordance or discordance, were handled as per the ‘Strategy I’ of the 2017 NACO/ NBTC guidelines [10]. Accordingly, all NAT-reactive donations were discarded, regardless of sero-reactivity. Sample testing was repeated in duplicate for further donor counselling and referral.All the initial reactive donors were recalled by the blood bank counsellor and were referred to the concerned authority or testing facility as per NACO/NBTC, after proper counselling and taking informed consent. Further evaluation, management, and follow-up evaluations of these individuals were performed by the appropriate clinical department.

Discordant results with NAT or serology were individually evaluated to resolve the discrepancy.

Data Handling, Statistical Analysis, Data Availability

All data were entered electronically and analysed using Microsoft Excel. For comparing NAT yields between TMA-based ID-NAT and PCR-based MP-NAT, Pearson Chi-square test was performed, with a p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. All other data were described descriptively. All datasets leading to the present conclusions are available with the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Committee and Informed Consents

This study represents a retrospective analysis of data collected routinely according to the standard operating policies of the blood bank. All donors were either voluntary or replacement donors, and gave their informed consent for serological and NAT testing of donated blood samples, including consent for HIV testing, as stipulated by applicable regulations. In addition, ethical approval from scientific committee for this study was also taken (Res/SCM/51/2022/30).

Results

Donor Profile and Serology

During the study period of 70 months, our blood bank processed a total of 48,151 donations, out of which 16,212 donations (33.7%) were screened by TMA-based ID-NAT (January 2015 to December 2016), and 31,939 donations (66.3%) were screened by PCR-based MP-NAT (January 2017 to October 2020). The results of serological testing of the blood donations are shown in Table 1. Male donors and replacement donors outnumbered female donors and voluntary donors respectively. Overall, 2.7% of samples were seroreactive, and the seroreactive samples were predominantly due to the three viral TTIs, with no malarial antigens detected in any of the donations. The proportion of seroreactive donations with viral TTIs remained similar throughout the study period. Among the seroreactive donations, HCV was the most commonly detected viral TTI followed by HBV and HIV (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Basic demographics of donors and results of serological tests during the study period

| Donations screened by ProcleixUltrio Plus TMA-based ID-NAT |

Donations screened by cobas®MPX2 PCR-based MP-NAT |

Overall donations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of donations | 16,212 | 31,939 | 48,151 |

| Time period | Jan 2015–Dec 2016 | Jan 2017–Oct 2020 | Jan 2015–Oct 2020 |

| Duration in months | 24 months | 46 months | 70 months |

| Gender of donors (N, %) | |||

| Male | 15,618 (96.3%) | 30,715 (96.2%) | 46,333 (96.2%) |

| Female | 594 (3.7%) | 1224 (3.8%) | 1818 (3.8%) |

| Type of donors (N, %) | |||

| Voluntary donors | 1028 (6.3%) | 1720 (5.4%) | 2748 (5.7%) |

| Replacement donors | 15,184 (93.7%) | 30,219 (94.6%) | 45,403 (94.3%) |

| Voluntary donors (N, %) | |||

| Male | 948 (92.2%) | 1567 (91.1%) | 2515 (91.5%) |

| Female | 80 (7.8%) | 153 (8.9%) | 233 (8.5%) |

| Overall | 1028 | 1720 | 2748 |

| Replacement donors (N, %) | |||

| Male | 14,670 (96.6%) | 29,148 (96.5%) | 43,818 (96.5%) |

| Female | 514 (3.4%) | 1071 (3.5%) | 1585 (3.5%) |

| Overall | 15,184 | 30,219 | 45,403 |

| Seroreactive donations (N, % of all donations) | |||

| Hepatitis B | 118 (0.7%) | 224 (0.7%) | 342 (0.7%) |

| Hepatitis C | 127 (0.8%) | 241 (0.8%) | 368 (0.8%) |

| HIV | 48 (0.3%) | 133 (0.4%) | 181 (0.4%) |

| Syphilis | 121 (0.7%) | 295 (0.9%) | 416 (0.9%) |

| Malaria | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Overall seroreactive donations | 413* (2.5%) | 892* (2.8%) | 1305* (2.7%) |

| Overall seroreactive donations for viral TTIs | 293 (1.8%) | 598 (1.9%) | 891 (1.9%) |

| Viral TTIs in seroreactive donations (N, % of all donations with viral TTIs) | |||

| Hepatitis B | 118 (40.4%) | 224 (37.5%) | 342 (38.5%) |

| Hepatitis C | 127 (43.5%) | 241 (40.4%) | 368 (41.4%) |

| HIV | 48 (16.4%) | 133 (22.3%) | 181 (20.4%) |

| Overall donations with viral TTIs | 292* (100%) | 597* (100%) | 889* (100%) |

*Two donations, one each with TMA-based ID-NAT and PCR-based MP-NAT, had HIV-HCV co-infection

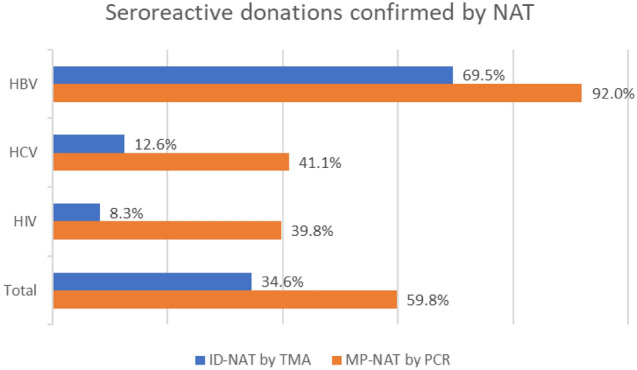

Fig. 3.

Proportion of seroreactive donations confirmed by two NAT techniques, for all three viral TTIs considered individually and together

Molecular Screening by NAT

The NAT results of the donations, with serological testing results of the donations throughout the study period are summarised in Table 2 and Fig. 3.PCR-based MP-NAT was able to detect 13 HBV infections and 1 HCV infection missed by serology, while TMA-based ID-NAT detected a total of 5 HBV infections missed by serology. The HBV NAT yield rate and the overall NAT yield rate were significantly higher with PCR-based MP-NAT compared to TMA-based ID-NAT (HBV yield rate, 1:3242 and 1:2457 for TMA-based ID-NAT and PCR-based MP-NAT respectively, p < 0.001; overall NAT yield rate, 1:3242 and 1:2281 for TMA-based ID-NAT and PCR-based MP-NAT respectively, p < 0.001). Notably, there were no HIV NAT yields throughout the study period. The proportion of overall seroreactive donations that were confirmed by NAT was higher with PCR-based MP-NAT (357/597, 59.8%) than with TMA-based ID-NAT (101/292, 34.6%); this proportion was higher with PCR-based MP-NAT thanTMA-based ID-NAT even with individual viral TTIs. (Fig. 3, Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of outcomes of serology and NAT in both the study periods with respect to the three viral TTIs. The NAT yield and NAT yield rate are also displayed

| ProcleixUltrio Plus TMA ID-NAT N = 16,212(2015–2016) |

Cobas®MPX2 PCR MP-NAT N = 31,939(2017–2020) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | HCV | HIV | Total | HBV | HCV | HIV | Total | |

| No of NAT reactive donations that were | ||||||||

| Seroreactive | 82 | 15 | 4 | 101* | 206 | 99 | 53 | 357 |

| Serononreactive (NAT yield) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Total NAT reactive donations | 87 | 15 | 4 | 106 | 219 | 101# | 52# | 371 |

| NAT yield rate | 1:3242 | – | – | 1:3242 | 1:2457 | 1:31,939 | – | 1:2281 |

| No of seroreactive donations that were | ||||||||

| NAT reactive | 82 | 16 | 4 | 101* | 206 | 99 | 53 | 357 |

| NAT nonreactive | 36 | 112 | 44 | 192 | 18 | 142 | 80 | 240 |

| Total seroreactive donations | 118 | 127 | 48 | 292* | 224 | 241 | 133 | 597 |

| Proportion of seroreactive donations that were | ||||||||

| NAT reactive | 69.5% | 12.6% | 8.3% | 34.6% | 92.0% | 41.1% | 39.8% | 59.8% |

| NAT nonreactive | 30.5% | 87.4% | 91.7% | 65.4% | 8.0% | 58.9% | 60.2% | 40.2% |

*One donation had HIV-HCV coinfection via serology, but was NAT reactive only for HIV and not for HCV; #One donation was HIV-reactive on serology but HCV-reactive on NAT

Discordance rates were low in both TMA-based ID-NAT as well as in PCR-based MP-NAT screening. During 2015–2016, one HIV-HCV co-infection detected by serological screening was detected as being HIV positive only on TMA-based ID-NAT screening. During 2017–2020, an incidence of true discordance was observed, in which serology was HIV-reactive, but PCR-based MP-NAT was HCV-reactive. Furthermore, during the same period, one sample had HIV-HCV coinfection through both serology and NAT.

Discussion

Many blood banks in India continue to depend on serological testing for donor screening, with only select blood banks, located in isolated geographies, using additional screening techniques such as NAT. This dependence of Indian blood banks on serology, which has a low sensitivity for TTI detection, has resulted in high number of TTIs in India. The NACO response to an RTI query in May 2016 reported that 2234 people across India contracted HIV through unsafe blood transfusions, over a duration of 17 months between October 2014 and March 2016 [11]. Supported by such observations, it has been realized that the introduction of universal NAT in Indian blood banks is an essential step to improve blood safety in India. Though some states in India have mandated NAT in blood banks [11], according to a 2017 review, only around 2% of all Indian blood banks (58/2550 blood banks) reported using NAT, and the NAT adaptation was found to be higher in North India compared to the rest of the country [12]. Perhaps the main deterrent for routine NAT in Indian blood banks is economic in origin. The additional cost incurred by routine testing of each donation using NAT invariably passes on to the patient’s pockets, especially since health insurance coverage is quite low in India [13].

There has been considerable literature on both formats of NAT [14–16]. Regardless of the format, previous studies have confirmed the value of NAT in the detection of sero-nonreactive samples harbouring viral TTIs [1, 17]. Our study adds to the existing literature by comparing the NAT yield rates of the two commonly used techniques of NAT. To our knowledge, our study is the first in India to do a comparison of the outcomes of two different NAT platforms in the same centre, albeit on two different set of donors at two different timeframes.

The major finding of our study is that the NAT yield rate with the PCR-based MP-NAT conducted on an automated platform was higher than that with the TMA-based ID-NAT conducted on a semiautomated platform at the same centre. Clinical specificity is higher when donations are screened in minipools rather than by individual donation. This is because screening in the minipool format requires detection of reactivity at both the pool and the individual sample level to assign reactivity to a donation [18]. Many blood banks outside the United States that screen donations in the ID-NAT format perform repeat testing on initially reactive donations, to improve specificity [19]. The high NAT yield with MP-NAT suggests that pooling did not affect the detection capacity of MP-NAT in minipools of 6. It has been debated that pooling of samples results in a reduced capacity of detection [20]; in contrast to this, cobas® MPX2 PCR MP-NAT confirmed more seroreactive donations and had higher NAT yields in our study than ProcleixUltrio Plus TMA ID-NAT. In another 2011 study comparing cobas® MPX in MP-NAT format and ProcleixUltrio in ID NAT format, 15 NAT yield donors who were MP-NAT reactive and ID-NAT non-reactive in index donations were reactive for serology (excluding HBsAg) at baseline or seroconverted on follow-up, thereby indicating the sensitivity of MP-NAT to detect window period donations and occult infections. However, the assay used in this study was different than those used in our study [21].

Apart from our study, a 2009 study from Thailand compared ProcleixUltrio ID-NAT and cobas®MPX MP-NAT and reported that the analytical sensitivity of both systems met the 95% limits of detection claimed by the respective package inserts. However, for HBV, ID-NAT was found to be less sensitive compared to MP-NAT [22]. Similarly, in our study too, we observed that the proportion of seroreactive donations which were also NAT reactive (in other words, NAT confirming seroreactive status) was higher with cobas® MPX2 in MP-NAT compared to ProcleixUltrio in ID-NAT. The 2011 study [22] comparing cobas® MPX in MP6 and ProcleixUltrio in ID formats respectively, had results on a similar line. It showed that of all seroreactive donations, 60.6% were also MP-NAT positive and only 39.4% were ID-NAT positive. The above study showed higher sensitivity of cobas® MPX used as MP than ProcleixUltrioas ID for detection of TTIs, especially NAT yields. Because the cobas® MPX 2 test reports reactivity on a target-specific basis, the blood bank is able to focus its additional testing of initially reactive donations and its assessment of donor risk factors on the specific viral target that is reported as reactive.

In our study, we observed a large number of seroreactive donations that were NAT-nonreactive; the proportion of such donations was higher with TMA-based ID-NAT compared to PCR-based MP-NAT. The reason for some seroreactive donations returning NAT-nonreactive is determined based on the serology cut-off values. For NAT-nonreactive but seroreactive donors with high serology cutoff values, this observation can be due to high antibody titres but low viremia, secondary to disease resolution with therapy or disease suppression, causing undetectable or absent viral genetic material [23, 24]. Most of these donors are in the late phase of the infection in which the viremia phase is over, with low levels of viral genetic material but high titres of antibodies. In fact, around 15–45% of patients with acute HCV infection are reported to undergo spontaneous resolution of infection; such individuals have circulating antibodies but do not harbour HCV RNA [25, 26]. Donors who have been immunized for HBV through HBsAg also tend to be seroreactive for HBsAg and NAT-nonreactive. Around 2–20% of HBsAg reactive donors have been reported in the past to have non-detectable HBV DNA, depending on the limits of detection of the assays used [27]. For seroreactive but NAT-nonreactive donors with low serology cut-off values, the seroreactive status is most likely because of false positive serology results. This is because; serological tests in blood centres are screening assays with high sensitivity.

The Roche MP-NAT used in our study is a fully automated system with ready to use reagents, and had a simpler algorithm with lesser steps, and the same assay was used for both screening and discriminatory assays; all these factors resulted in a user-friendly experience, and we found it easier to operate than the ID-NAT format. By contrast, the ID-NAT assay used in our study was a semi-automated system which required manual pre-analytical work with skilled personnel. Further, the samples for ID-NAT have to be thawed and brought to room temperature before using: this increased the turn-around time. The higher pre-analytical preparatory steps with the ProcleixUltrio-Plus (ID-NAT) requires a contamination free room; by contrast, since there is no need for manual pre-analytical work with the cobas® MPX 2 (MP-NAT), we observed that the chances of contamination are lower.

This is especially significant in the Indian setting, where it has been observed that the training and motivation among the blood bank technologists and in-charges is quite low, due to a variety of reasons [28]. Additionally, the cobas® MPX2 test is a multiplex PCR test that has the ability to simultaneously detect a reactive donation and identify the target virus (HBV, HCV or HIV) with specific dyes in different channels in a single step. This eliminates the need for additional discriminatory testing in reactive donation samples. Moreover, since there is pooling of samples, the reagent requirements and costs of operation are lower with MP-NAT than ID-NAT [12]. The cost of accessories for pre-analytical work is also lower with cobas® MPX2, and the workflow algorithm in ProcleixUltrio Plus assay that needs running in triplicates for each tests further adds to the cost. All these points contribute to the lower overall costs of MP-NAT compared to ID-NAT [14, 22]. Additionally, as seen in our study, cobas® MPX2 PCR MP-NAT was associated with higher number of NAT-reactive samples, higher NAT yield, and higher NAT yield rate. Furthermore, the proportion of seroreactive donations confirmed by NAT was also higher with cobas® MPX2 PCR MP-NAT. While cobas® MPX2 assay detects both HIV-1 and HIV-2, ProcleixUltrio-Plus assay detects only HIV-1. The genotypic coverage (for HBV and HCV) is also higher with cobas® MPX2 than ProcleixUltrio-Plus [6, 7, 9, 29]. All these observations suggest that cobas® MPX2 PCR MP-NAT might be more affordable and user friendly, and thus, more feasible in Indian setting.

Our study is not without limitations. Our results are experiences from a single centre in North India: though valuable, they form just one part of the overall community picture. We did not do a viral load comparison between both the formats. Further, the two NAT formats were used to screen different donor populations in different time periods. A comparison of the cost-effectiveness of ID-NAT and MP-NAT would have provided an additional indicator to evaluate these two types of NAT. Further, future studies with additional serology assays and follow up of the serology and NAT reactives would be useful to understand the true difference between the assays.

Conclusion

To conclude, our study indicates that cobas® MPX2 PCR-based MP-NAT is associated with higher NAT yield rates as well as higher rates of confirmation of seropositive donations when compared to TMA-based ID-NAT. PCR-based MP-NAT has additional advantages, such as lower cost, greater ease of operation due to being fully automated, and simpler testing algorithm. TMA-based ID-NAT too could detect TTIs, however it was less sensitive in identifying seropositives. Screening donor samples with TMA-based ID-NAT was comparatively expensive with added pre-analytical work and complicated testing algorithm with triplicate screening and need for further testing for viral discrimination. More studies are required to explore the cost-effectiveness of routine NAT use in blood banks, and to further evaluate the pros and cons of the two formats of NAT from an Indian perspective. A national policy update that makes NAT mandatory irrespective of the testing format (either MP-NAT or ID-NAT), as part of the routine blood donation screening process is highly essential to improve blood safety.

Acknowledgements

Authors take full responsibility for the content of the manuscript. Medical writing services were provided by Marks Man Healthcare Communications Pvt Ltd., India.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The identity of the patient is not disclosed here in this case. The authors state that there is no conflict of interest present.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amardeep Pathak, Email: amardeep_12@yahoo.com.

Devasis Panda, Email: devasis.f@gmail.com.

Manushri Sharma, Email: manushri.sharma30@gmail.com.

Narender Tejwani, Email: mbbsnt@gmail.com.

Anurag Mehta, Email: mehta.anurag@rgcirc.org.

References

- 1.Pathak S, Chakraborty T, Singh S, Dubey R. Impact of PCR-based multiplex minipool NAT on donor blood screening at a tertiary care hospital blood bank in North India. Int J Med Sci Current Res. 2021;4(1):570–575. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hans R, Marwaha N. Nucleic acid testing-benefits and constraints. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8(1):2–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safic Stanic H, Babic I, Maslovic M, Dogic V, Bingulac-Popovic J, Miletic M, et al. Three-year experience in NAT screening of blood donors for transfusion transmitted viruses in croatia. Transfus Med Hemother. 2017;44(6):415–420. doi: 10.1159/000457965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee K, Coshic P, Borgohain M, Premchand RM, Thapliyal CS, et al. Individual donor nucleic acid testing for blood safety against HIV-1 and hepatitis B and C viruses in a tertiary care hospital. National Med J India. 2012;25(4):207–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Standards for blood banks & blood transfusion services: national AIDS control organization; 2007 [cited 2021 Sept 13]. Available from: http://www.naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/Standards%20for%20Blood%20Banks%20and%20Blood%20Transfusion%20Services.pdf

- 6.ProcleixUltrioPlus Assay product insert. 502432 Rev [13]A, 2012, USA. Gen-Probe, Incorporated

- 7.ProcleixUltrio Assay product insert. 502623 Rev A, 2012, USA. Gen-Probe, Incorporated

- 8.Chaurasia R, Rout D, Zaman S, Chatterjee K, Pandey HC, Maurya AK. Comparison of procleix ultrio elite and procleix ultrio NAT assays for screening of transfusion transmitted infections among blood donors in india. Int J Microbiol. 2016;2016:2543156. doi: 10.1155/2016/2543156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.cobasTaqScreen MPX test, version 2.0 for use on the cobas s201 System: Doc Rev4, 2014, USA. Roche Molecular Systems, Inc

- 10.Guidelines for blood donor selection and blood donor referral: national AIDS control organization (NACO), national blood transfusion services (NBTC), ministry of health and family welfate, Govt of India; 2017 [cited 2021 21 Oct]. Available from: http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/Letter%20reg.%20%20guidelines%20for%20blood%20donor%20selection%20%26%20referral%20-2017.pdf.

- 11.Rajput MK. Regulation of molecular diagnostic (NAT) kits for HBV, HCV and HIV in India. J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2017;11(3):Kl01. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24131.9337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh K, Mishra K. Nucleic acid amplification testing in Indian blood banks: A review with perspectives. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2017;60(3):313–318. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_361_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang A, Dang D, Vallish BN. Importance of evidence-based health insurance reimbursement and health technology assessment for achieving universal health coverage and improved access to health in India. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;24:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrashekar S. Half a decade of mini-pool nucleic acid testing: cost-effective way for improving blood safety in India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8(1):35–38. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hans R, Marwaha N, Sharma S, Sachdev S, Sharma RR. Initial trends of individual donation nucleic acid testing in voluntary & replacement donors from a tertiary care centre in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149(5):633–640. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_822_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain R, Aggarwal P, Gupta GN. Need for nucleic acid testing in countries with high prevalence of transfusion-transmitted infections. ISRN Hematol. 2012;2012:718671. doi: 10.5402/2012/718671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta S, Khillan K, Ranjan V, Wattal C. Nucleic acid amplification test: bridging the gap in blood safety & re-evaluation of blood screening for cryptic transfusion-transmitted infection among Indian donors. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149(3):389–395. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1340_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galel SA, Simon TL, Williamson PC, AuBuchon JP, Waxman DA, Erickson Y, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a new automated system for the detection of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus nucleic acid in blood and plasma donations. Transfusion. 2018;58(3):649–659. doi: 10.1111/trf.14457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weusten J, Vermeulen M, van Drimmelen H, Lelie N. Refinement of a viral transmission risk model for blood donations in seroconversion window phase screened by nucleic acid testing in different pool sizes and repeat test algorithms. Transfusion. 2011;51(1):203–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee K, Agarwal N, Coshic P, Borgohain M, Chakroborty S. Sensitivity of individual and mini-pool nucleic acid testing assessed by dilution of hepatitis B nucleic acid testing yield samples. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8(1):26–28. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louisirirotchanakul S, Oota S, Khuponsarb K, Chalermchan W, Phikulsod S, Chongkolwatana V, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in Thai blood donors. Transfusion. 2011;51(7):1532–1540. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phikulsod S, Oota S, Tirawatnapong T, Sakuldamrongpanich T, Chalermchan W, Louisirirotchanakul S, et al. One-year experience of nucleic acid technology testing for human immunodeficiency virus type 1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus in Thai blood donations. Transfusion. 2009;49(6):1126–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar R, Gupta S, Kaur A, Gupta M. Individual donor-nucleic acid testing for human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus and its role in blood safety. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2015;9(2):199–202. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.154250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makroo RN, Choudhury N, Jagannathan L, Parihar-Malhotra M, Raina V, Chaudhary RK, et al. Multicenter evaluation of individual donor nucleic acid testing (NAT) for simultaneous detection of human immunodeficiency virus -1 & hepatitis B & C viruses in Indian blood donors. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127(2):140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong F, Pan Y, Chi X, Wang X, Chen L, Lv J, et al. Factors associated with spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus in Chinese population. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:527030. doi: 10.1155/2014/527030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta E, Bajpai M, Choudhary A. Hepatitis C virus: screening, diagnosis, and interpretation of laboratory assays. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8(1):19–25. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.126683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Candotti D, Laperche S. Hepatitis B virus blood screening: need for reappraisal of blood safety measures? Front Med. 2018;5:29. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naidu NK, Bharucha ZS, Sonawane V, Ahmed I. Nucleic acid testing: Is it the only answer for safe Blood in India? Asian J Transfus Sci. 2016;10(1):79–83. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.175423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajput MK. Automated triplex (HBV, HCV and HIV) NAT assay systems for blood screening in India. J Clin Diag Res JCDR. 2016;10(2):Ke01-4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16981.7319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]