Abstract

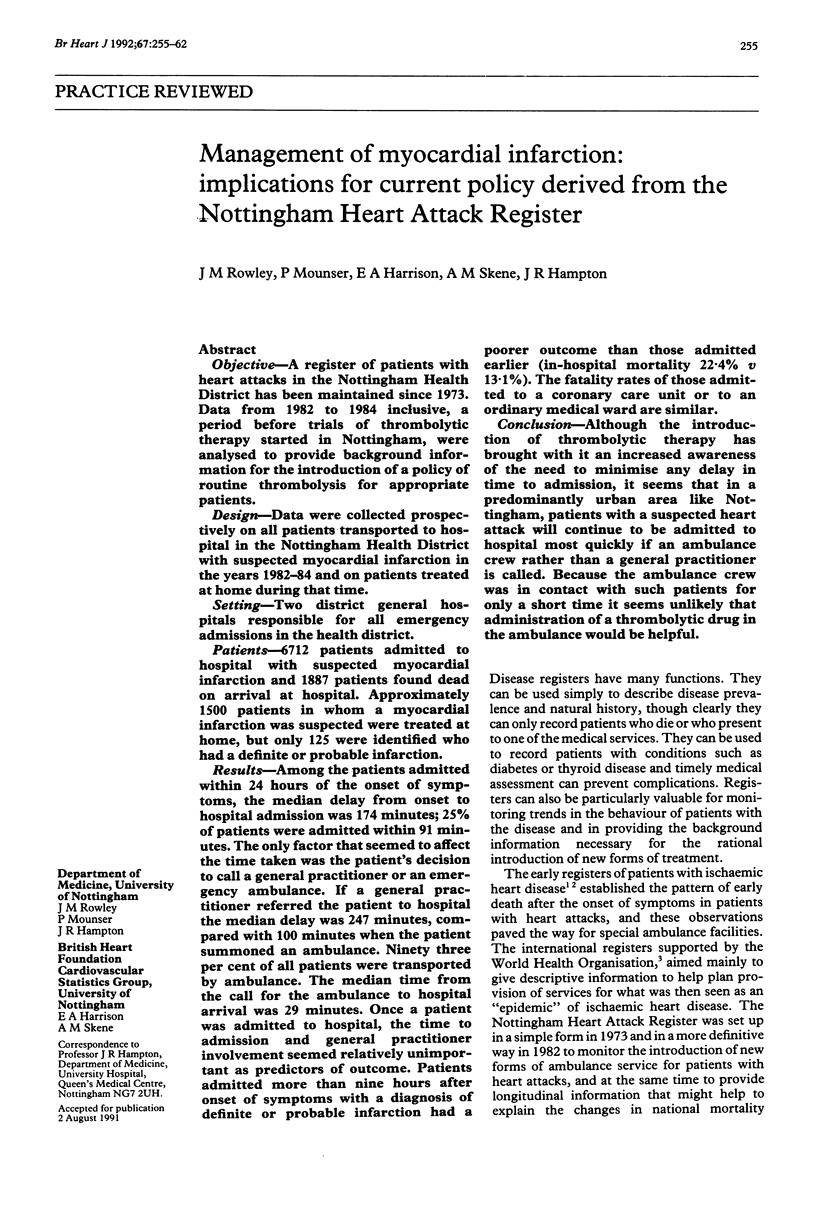

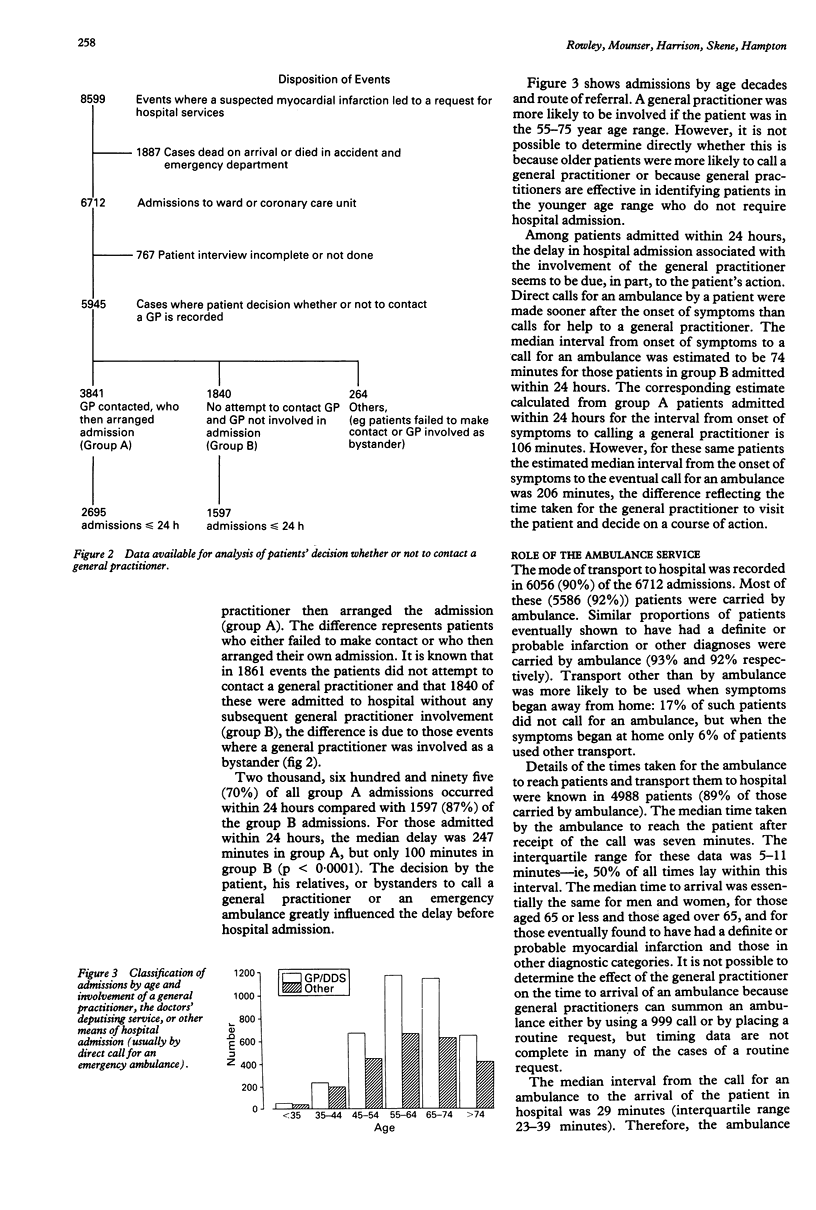

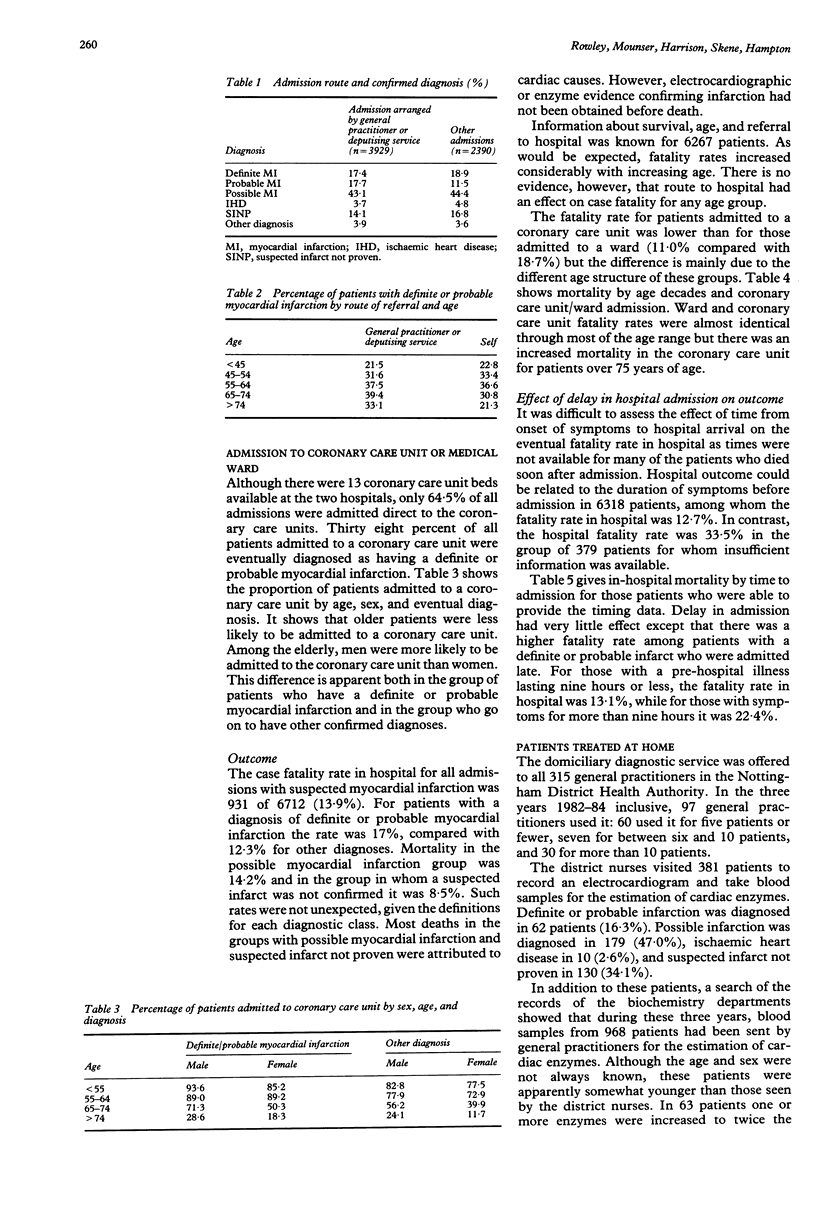

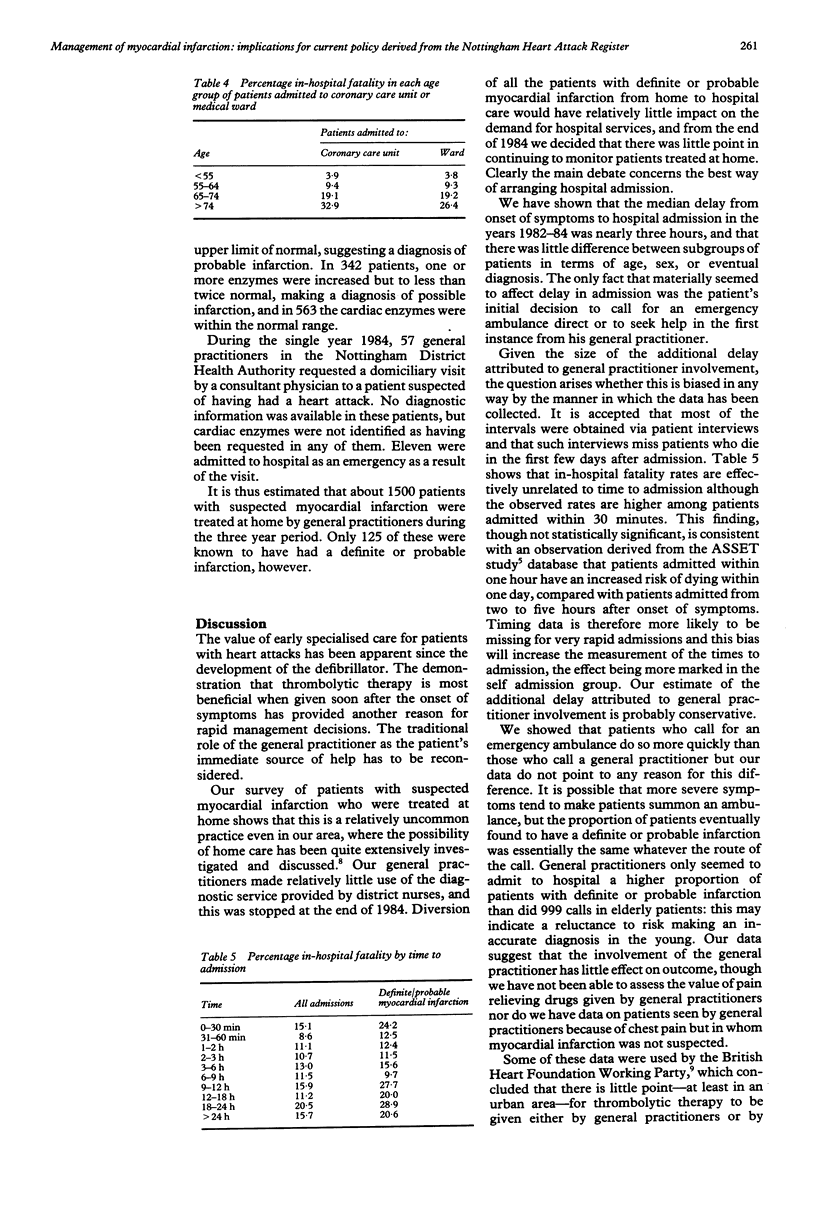

OBJECTIVE--A register of patients with heart attacks in the Nottingham Health District has been maintained since 1973. Data from 1982 to 1984 inclusive, a period before trials of thrombolytic therapy started in Nottingham, were analysed to provide background information for the introduction of a policy of routine thrombolysis for appropriate patients. DESIGN--Data were collected prospectively on all patients transported to hospital in the Nottingham Health District with suspected myocardial infarction in the years 1982-84 and on patients treated at home during that time. SETTING--Two district general hospitals responsible for all emergency admissions in the health district. PATIENTS--6712 patients admitted to hospital with suspected myocardial infarction and 1887 patients found dead on arrival at hospital. Approximately 1500 patients in whom a myocardial infarction was suspected were treated at home, but only 125 were identified who had a definite or probable infarction. RESULTS--Among the patients admitted within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms, the median delay from onset to hospital admission was 174 minutes; 25% of patients were admitted within 91 minutes. The only factor that seemed to affect the time taken was the patient's decision to call a general practitioner or an emergency ambulance. If a general practitioner referred the patient to hospital the median delay was 247 minutes, compared with 100 minutes when the patient summoned an ambulance. Ninety three per cent of all patients were transported by ambulance. The median time from the call for the ambulance to hospital arrival was 29 minutes. Once a patient was admitted to hospital, the time to admission and general practitioner involvement seemed relatively unimportant as predictors of outcome. Patients admitted more than nine hours after onset of symptoms with a diagnosis of definite or probable infarction had a poorer outcome than those admitted earlier (in-hospital mortality 22.4% v 13.1%). The fatality rates of those admitted to a coronary care unit or to an ordinary medical ward are similar. CONCLUSION--Although the introduction of thrombolytic therapy has brought with it an increased awareness of the need to minimise any delay in time to admission, it seems that in a predominantly urban area like Nottingham, patients with a suspected heart attack will continue to be admitted to hospital most quickly if an ambulance crew rather than a general practitioner is called. Because the ambulance crew was in contact with such patients for only a short time it seems unlikely that administration of a thrombolytic drug in the ambulance would be helpful.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armstrong A., Duncan B., Oliver M. F., Julian D. G., Donald K. W., Fulton M., Lutz W., Morrison S. L. Natural history of acute coronary heart attacks. A community study. Br Heart J. 1972 Jan;34(1):67–80. doi: 10.1136/hrt.34.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colling A., Dellipiani A. W., Donaldson R. J., MacCormack P. Teesside coronary survey: an epidemiological study of acute attacks of myocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1976 Nov 13;2(6045):1169–1172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6045.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. D., Hampton J. R., Mitchell J. R. A randomised trial of home-versus-hospital management for patients with suspected myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1978 Apr 22;1(8069):837–841. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. D., Holdstock G., Hampton J. R. Comparison of mortality of patients with heart attacks admitted to a coronary care unit and an ordinary medical ward. Br Med J. 1977 Jul 9;2(6079):81–83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6079.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlen L. J. Incidence and presentation of myocardial infarction in an English community. Br Heart J. 1973 Jun;35(6):616–622. doi: 10.1136/hrt.35.6.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai G. R., Haites N. E., Rawles J. M. One thousand heart attacks in Grampian: the place of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Feb 7;294(6568):352–354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6568.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedoe H. T., Clayton D., Morris J. N., Brigden W., McDonald L. Coronary heart-attacks in East London. Lancet. 1975 Nov 1;2(7940):833–838. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley J. M., Hill J. D., Hampton J. R., Mitchell J. R. Early reporting of myocardial infarction: impact of an experiment in patient education. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 Jun 12;284(6331):1741–1746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6331.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyllie H. C., Taylor M. P., Cuninghame-Green R. A. Acute myocardial infarction in Doncaster. II. Delays in admission and survival. Br Med J. 1972 Jan 1;1(5791):34–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5791.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox R. G., von der Lippe G., Olsson C. G., Jensen G., Skene A. M., Hampton J. R. Trial of tissue plasminogen activator for mortality reduction in acute myocardial infarction. Anglo-Scandinavian Study of Early Thrombolysis (ASSET). Lancet. 1988 Sep 3;2(8610):525–530. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]