Abstract

Reproductive isolation poses a major obstacle to wide hybridization and introgression breeding of plants. Hybrid inviability in the postzygotic isolation barrier inevitably reduces hybrid fitness, consequently causing hindrances in the establishment of novel genotypes from the hybrids among genetically divergent parents. The idea that the plant immune system is involved in the hybrid problem is applicable to the intra- and/or interspecific hybrids of many different taxa. The lethality characteristics and expression profile of genes associated with the hypersensitive response of the hybrids, along with the suppression of causative genes, support the deleterious epistatic interaction of parental NB-LRR protein genes, resulting in aberrant hyper-immunity reactions in the hybrid. Moreover, the cellular, physiological, and biochemical reactions observed in hybrid cells also corroborate this hypothesis. However, the difference in genetic backgrounds of the respective hybrids may contribute to variations in lethality phenotypes among the parental species combinations. The mixed state in parental components of the chaperone complex (HSP90-SGT1-RAR1) in the hybrid may also affect the hybrid inviability. This review article discusses the facts and hypothesis regarding hybrid inviability, alongside the findings of studies on the hybrid lethality of interspecific hybrids of the genus Nicotiana. A possible solution for averting the hybrid problem has also been scrutinized with the aim of improving the wide hybridization and introgression breeding program in plants.

Keywords: Plant breeding, Wide hybridization, Nicotiana species, Hybrid inviability, Plant immune system, Chaperone complex

Introduction

Sustainable agriculture fulfills an essential and urgent need for food security in an era of global climate change and population explosion. To cope with this issue, the development of a more efficient farming system, as well as novel cultivars that tolerate severe environments, should be considered. Above all, plant breeding based on both conventional and molecular technologies plays an important role in developing genotypes with enhanced characteristics that are better suited for accommodating climate change conditions. Although molecular breeding—including genome editing technology—is useful for further improving the elite cultivars (Basso et al. 2020), crossbreeding using landraces and wild relatives as a parent has the potential to address both biotic and abiotic stresses in the absence of objective genetic resources or functional information of genes in pre-existing cultivars or genome informatics. One such successful example is the NERICA (the New Rice for Africa) cultivars which were created by crossing African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and Asian rice (O. sativa), thus combining the tolerance of O. glaberrima to a harsh environment and the high yield potential of O. sativa. These cultivars have consequently played a prominent role in the harvest of rice in African countries (FAO 2011). Another example is Triticale, a self-pollinated cereal crop developed by crossing wheat (Triticum spp.) and rye (Secale cereale). This man-made crop adapts to wider environmental conditions—wherein it can be grown with stronger tolerance to stress conditions than normal wheat—but research for the improvement of its agronomical and nutritional traits is still underway (Mergoum et al. 2019). Efforts to prepare the interspecific hybrids among the plant species belonging to 46 genera were described in a book on plant breeding published in 1957 (Kagawa 1957). This means that enrichment of the cultivated germplasm with valuable traits by wide hybridization has been important for crop improvement. Examples of valuable cultivars developed by interspecific hybridization were reported in multiple crops (Singh et al. 2021). To this end, the application of useful genes belonging to a wild source is beneficial to further crop improvement (von Wettberg et al. 2020), making the wide hybridization and introgression breeding program a valid tool for addressing drought, pest, and disease in the near future.

However, hybrid inviability (HI)—often observed in the hybrid progenies among the distantly related species—is a major drawback of wide hybridization and introgression breeding, leading to a reduction in the probability of obtaining the hybrids with the desired gene combination of the parents. HI is a class of postzygotic isolating barriers found in both plants and animals that cause developmental difficulties, with full or partial lethality in the hybrid progenies (Coyne and Orr 2004). While many examples of reproductive isolation in native plant taxa were reported (Baack et al. 2015), inviability of interspecific F1 or F2 hybrid progenies of several important crops was well documented, e.g., rice (Chen et al. 2014), wheat (Mizuno et al. 2010), rye (Ren and Lelley 1988), potato (Valkonen and Watanabe 1999), tomato (Krüger et al. 2002), tobacco (Mino et al. 2002; Tezuka et al. 2010), cotton (Deng et al. 2019), apple (Schuster 2000), pear (Montanari et al. 2016), and grapes (Filler et al. 1994). Consequently, HI poses a major obstacle to wide hybridization and introgression breeding programs in agronomically important plants. Although in vitro techniques that rescue the hybrid embryos are effective in reducing some types of incompatibility in distant hybridization (Pramanik et al. 2021), hybrid lethality (HL)—a type of HI that is usually observed in the hybrids at the seedling or later growing stage—is doomed to hinder the ultimate goal of the breeding program. Consequently, strict regulation of the HL fosters more efficient wide hybridization breeding. Thus, it is worth considering the underlying mechanisms and functions of HL in order to facilitate the efficacy of wide hybridization breeding.

The present review describes the HL identified in the interspecific hybrids of the genus Nicotiana, one of the largest genera in the family Solanaceae, which contains 83 species subdivided into 13 sections (Berbeć and Doroszewska 2020). It was reported in the literature prior to 2019 that 445 combinations of the Nicotiana interspecific hybrids have been produced, but several of them could not survive beyond the seedling stage (Berbeć and Doroszewska 2020). Several wild Nicotiana species are resistant to diseases and pests that are harmful to common tobacco plants, indicating that they are valuable resources for tobacco plant improvement. Despite the public health threats of cigarette smoking, tobacco has been considered as a useful medicinal plant, along with the potential to obtain novel biologically active molecules (Sanchez-Ramos 2020) and ornamental value. Thus, this apparent significance of the plant necessitates further improvement of its hybrid species.

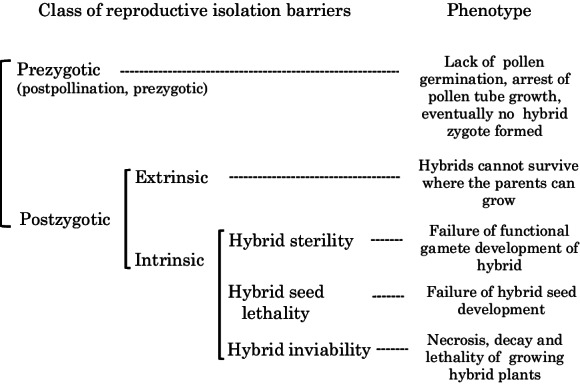

Plant reproductive isolating barrier

Although the present review is not intended to be comprehensive, preceding the discussion of the HL of Nicotiana interspecific hybrids is a brief overview of the two major reproductive isolation barriers—i.e., prezygotic and postzygotic barriers (Fig. 1). Prezygotic barriers—more precisely, post-pollination and prezygotic barriers in the context of artificial hybridization—are the form of gametic isolation that manifests as pollen-pistil (stigma and style) cross-incompatibility. Lack of pollen germination on the stigma and arrest of pollen tube growth in the style, eventually leading to deterrence in hybrid zygote formation, comprise the typical features. This incompatibility has been reported in various interspecific hybrids of several plant taxa, e.g., Capsicum (Onus and Pickersgill 2004), Sorghum (Hondnett et al. 2005), Sesamum (Ram et al. 2006), Solanum (Baek et al. 2015), Prunus (Szymajd et al. 2015), and Arabidopsis (Müller et al. 2016). The mechanisms linked to self-incompatibility (SI) are involved in pollen-pistil interspecific reproductive barrier; e.g., unilateral incompatibility (UI)—one cross direction between parental species fails hybrid seed production but the reciprocal cross succeeds—observed among species in the tomato clade (Solanum section Lycopersicon) relates to the action of SI genes (Baek et al. 2015). By contrast, the presence of genetic factors apart from the SI locus has been suggested to be involved in cross-incompatibility among the species hybrids of asparagus (Marcellán and Camadro 1996), carrot (Ibañez and Camadro 2015), and potato (Maune et al. 2018). SI independent factors involved in UI between maize and teosinte (Kermicle 2006; Liu et al. 2019), as well as an interspecies barrier in Brassicaceae (Li et al. 2018; Fujii et al. 2019), have also been reported. More comprehensive information about pollen-pistil interaction as a reproductive isolating barrier can be found in a recent review article by Broz and Bedinger (2021).

Fig. 1.

Classification of plant reproductive isolation barriers

Postzygotic barriers consist of both extrinsic and intrinsic causes. The former depends on the environmental conditions in which the parents can grow, but their hybrids are difficult to survive. For example, the F1 hybrids between two neighboring populations of Senecio lautus—each inhabits respectively sand dune and rocky headlands—suffered more individual losses to predators and dry conditions than their parents (Melo et al. 2014). In contrast, the latter stems from the genotype of the hybrids, leading to developmental problems that are relatively independent of the environmental conditions. Intrinsic postzygotic isolation barriers are further divided into hybrid sterility, hybrid seed lethality (HSL), and HI. The Dobzhansky-Muller (DM) model explains the genetics of postzygotic isolation barriers: deleterious epistatic interaction between two parental loci results in hybrid problems among the species, although the loci function normally in the parents, which are perfectly viable and fertile (Coyne and Orr 2004).

While examples of intra- and interspecific hybrid sterility have been observed in several plant taxa (Moyle and Nakazato 2008; Sweigart and Flagel 2015; Simon et al. 2016), the causal genes for hybrid sterility have been extensively analyzed in intersubspecific rice hybrid (Oka 1974; Yanagihara et al. 1992; Wan et al. 1996; Song et al. 2005; Zhu et al 2005; Wang et al 2006; Li et al. 2007, 2020; Zhao et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2008, 2017). To this end, more than 50 sterility loci belonging primarily to nuclear genes have been genetically identified, and 10 loci relating to hybrid sterility were cloned and characterized at a molecular level (Li et al. 2020). Negative interaction between various alleles at a single locus and/or various alleles with other loci is the genetic cause of intersubspecific hybrid sterility of Oryza sativa (Ouyang and Zhang 2013), and this is the case for interspecific hybrid sterility between O. sativa and its relative species (Li et al. 2020). Besides, a sterility locus (qHMS7) containing two tightly linked open reading frames (ORF2 and ORF3) that affect pollen viability was found in F1 hybrids between O. sativa and O. marionalis (Yu et al. 2018). Recent advancement of research on genetic factors for hybrid sterility of rice can be seen in a review by Li et al (2020).

Chromosome pairing abnormalities—eventually producing non-viable gametes—in hybrids are another dynamic involved in the generation of hybrid sterility (Stebbins 1971). The occurrence of meiotic abnormality in F1 hybrid depends on the lack of chromosomal pairing caused by non-homologous DNA sequence between parental species. The low similarity in the sequences between parental chromosome sets inhibits the single strand-based DNA homology search in prophase I and diminishes the number of D-loop structure which is required for homologous pairing, synapsis, and recombination (Storme and Mason 2014). Though the spontaneous formation of unreduced gametes by the action of meiotic restitution occasionally produces seeds on interspecific hybrid plants (Zhang et al. 2008; Chung et al. 2013), artificial chromosome doubling and production of amphidiploids are the most common methods for restoring fertility in this type of hybrid sterility.

HSL and HI act as potent hindrances to wide hybridization breeding, as it forcibly increases the loss of the seeds and plants of F1 hybrid. HSL―usually associated with failure of hybrid endosperm development―was observed in the interspecific F1 hybrid of Mimulus (Oneal et al. 2016), tomato (Florez-Rueda et al. 2016), and Arabidopsis (Lafon-Placette et al. 2017). As distinct patterns of HLS are observed in reciprocal crosses between species, genetic loci with parent-of-origin effects that relate to defects in genomic imprinting are involved in this hybrid lethality (Fishman and Sweigart 2018; Ouyang and Zhang 2018). On the other hand, the features of plant HI are reminiscent of hyperactivation of plant defense responses, characterized by necrosis, decay, and lethality of hybrid plants. The factors involved in plant HI are usually loci encoding components of the plant immune system, primarily NLR protein genes (Bomblies 2010). As the sequences of these protein genes are quite diverse due to the long-term battle between plants and pathogens (Baggs et al. 2017), deleterious DM-type interactions among parental NLR genes provoke improper hyper-immunity in the hybrid as a corollary of “collateral damage of NLR diversity” (Barragan and Weigel 2021). A hybrid problem caused by the involvement of the plant immune system has been observed in tomato (Krüger et al. 2002), Arabidopsis (Bomblies et al. 2007), lettuce (Jeuken et al. 2009), Capsella (Sicard et al. 2015), cabbage (Xiao et al. 2017), rice (Yamamoto et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2014), cotton (Deng et al. 2019), and tobacco (Ma et al. 2020). Up-to-date information about the roles of autoimmunity in plant hybrid inviability was comprehensively compiled in a recent review article by Calvo-Baltanás et al. (2021).

HL of Nicotiana interspecific hybrids

Fifty-three species of Nicotiana subdivided into twelve sections inhabit the North and South American continents. On the other hand, the largest section Suaveolentes has diverged to form about 30 species in the Australian continent and surrounding Pacific islands, while another species belonging to this section, N. africana, is endemic in Namibia of Southern Africa (Chase et al. 2018). The species belonging to the Nicotiana section (N. sect.) Suaveolentes are allopolyploid; hence, they are of hybrid origin, followed by dysploidy chromosome number reduction, and eventually formed as aneuploid species within the section. The ancestor species of this section arose from hybridization between a progenitor of N. sylvestris (a progenitor of N. tabacum) as a paternal parent and an unidentified maternal parent, and the additional possibility of this species being formed from the ancestral species of section Noctiflorae and Petunioides was presented (Kelly et al. 2012; Clarkson et al. 2017). As this has occurred approximately six million years ago in South America, where N. tabacum originated (Clarkson et al. 2017), the species in N. sect. Suaveolentes were isolated temporally as well as spatially from N. tabacum. However, the details regarding intercontinental relocation or dispersal of the progenitor remain an enigma (Chase et al. 2018).

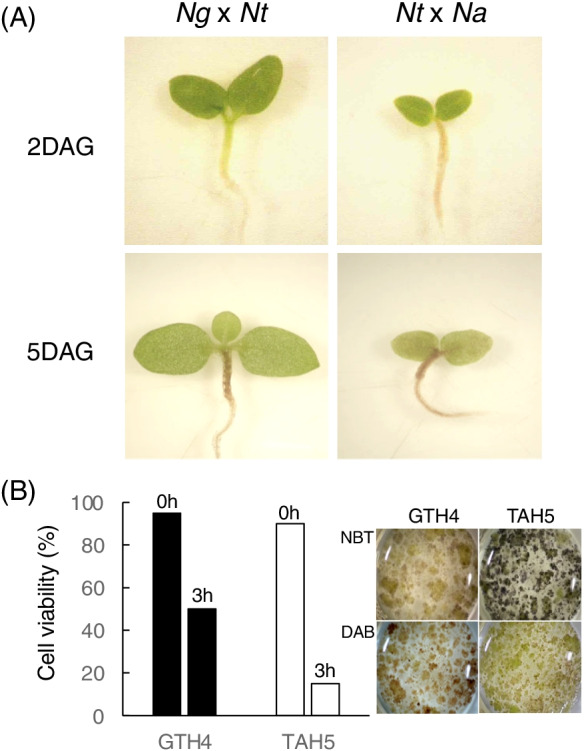

Marubashi et al. have extensively studied the nature of lethality existing in the Nicotiana interspecific hybrids, especially the hybrids between several species of N. sect. Suaveolentes and N. tabacum (Yamada et al. 1999; 2000; 2001; Marubashi and Kobayashi 2002; Masuda et al. 2003; Yamada and Marubashi 2003; Kobori et al. 2005). Moreover, Yamada et al. (1999) classified the lethal phenotype of the Nicotiana F1 hybrid seedlings into four types (types I–IV), of which respective species hybrid combinations complied. It was observed that the expression of three types (types I–III) of lethality was suppressed at permissive temperatures (ca. 36 °C), but type IV lethality was not. Subsequently, another temperature-dependent lethality (type V) was identified in the F1 hybrid between N. tabacum and N. occidentalis (N. sect. Suaveolentes) (Tezuka and Marubashi 2012) (five lethality phenotypes were listed in Appendix 1). Furthermore, HL found in the hybrids between species of N. sect. Suaveolentes and N. tabacum generally complied with type II lethality, characterized by browning of the hypocotyls and roots in the seedlings after germination (Fig. 2A). As N. tabacum—a natural amphidiploid with component genomes S and T—was originated from hybridization of two ancestral species, i.e., N. sylvestris (SS) and N. tomentsiformis (TT), a role of subgenome (S or T) which contributes to the lethality of F1 hybrid between N. tabacum and species of N. sect. Suaveolentes can be analyzed by using those ancestral species. Based on the hybridization of N. suaveolens and N. debneyi with the two ancestral species, the causative factors of HL in N. tabacum were shown to be present in the S subgenome (Inoue et al. 1996; Tezuka et al. 2007). The location of one causative factor of HL was subsequently narrowed down to the Q chromosome of the S subgenome by crossing between N. suaveolens and the monosomic line series of N. tabacum with chromosome-specific DNA markers (Marubashi and Onosato 2002; Tezuka and Marubashi 2006). Similar outcomes were observed for ten other Suaveolentes species (Tezuka et al 2007; 2010; 2012), suggesting that these species have a common factor that deleteriously interacts with the factor present on the Q chromosome of N. tabacum. However, F1 hybrids between N. tabacum and two species of N. sect. Suaveolentes—N. benthamiana and N. fragrans—did not exhibit any lethality (DeVerna et al. 1987; Tezuka et al. 2010), suggesting that such a common factor is absent or functionally suppressed in these two species. Based on this finding, Iizuka et al. (2012) conducted a genetic analysis of the causative genes for HL in species of N. sect. Suaveolentes; they analyzed lethal phenotype segregation in the populations from the three-way cross of (N. debneyi × N. fragrans) × N. tabacum. Heterozygosity (+ / −) at HL locus in F1 hybrid (N. debneyi (+ / +) × N. fragrans (− / −)) was expected to give a ratio of 1:1 segregation for lethal and non-lethal phenotype in the populations from the three-way cross. To this end, they named the causative allele in Suaveolentes species as Hla1-1 at the hybrid lethality A1 (HLA1) locus after a thorough analysis of lethal phenotype segregation in the trispecific hybrid populations.

Fig. 2.

(A) Type II lethality of F1 hybrid seedling of N. gossei (Ng) × N. tabacum (Nt) and N. tabacum (Nt) × N. africana (Na) 2 and 5 days after germination (DAG) at 26 °C. Note that browning of hypocotyl and root, along with growth arrest, appeared earlier in Nt × Na. (B) Viability of cultured F1 hybrid cells of GTH4 (Ng × Nt) and TAH5 (Nt × Na), 0 and 3 h after transferring from 37 to 26 °C (left panel). Detection of cellular O2・- and H2O2 by nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), respectively (right panel). The cells were observed 40 min after the temperature shift was shown. Note that TAH5 generated more O2・-, while GTH4 generated more H2O2 at the same time points (Mino and Shomura, unpublished data)

On the other hand, Ma et al. (2020) reported that Nt6549g30—encoding NLR protein of N. tabacum—is a causative factor that provokes HL by crossing with any of nine species of N. sect. Suaveolentes including N. africana. A factor locating on the H chromosome (corresponding to be linkage group 11) in N. tabacum has been thought of as a trigger for HL by crossing with N. africana (Gerstel et al. 1979; Hancock et al. 2015). Bindler et al. (2011) reported that linkage group 11 in N. tabacum created by large-scale microsatellite markers belonged to the S subgenome. Furthermore, Tezuka et al. (2012) indicated that several SSR markers for linkage group 11 correspondingly detected the Q chromosome. According to this collective evidence, Nakata et al. (2021) considered that the H chromosome mentioned by Hancock et al. (2015) and Ma et al. (2020) is the same as the Q chromosome. Knockout of Nt6549g30 by the CRISPR-Cas9 system suppressed the HL in the hybrids between species of N. sect. Suaveolentes and N. tabacum (Ma et al. 2020), thus confirming that this gene is involved in HL. Nakata et al. (2021) reported that Nt6549g30 is located on the distal part of the Q chromosome, and deletion of this part of the chromosome overcame the HL of the F1 hybrid between N. suaveolens and N. tabacum. In summary, these outcomes indicate that the factor for HL in N. tabacum—which interacts with the corresponding factor (Hla1-1) in the respective species of N. sect. Suaveolentes—is located on the Q chromosome (linkage group 11) of the S subgenome, and it is an NLR gene that induces a hyper-immunity reaction in the hybrid. Tezuka et al. (2021) recently reported that the HLA1 locus of N. debneyi was mapped to a linkage group LG1. Further analysis using CAPS markers revealed that the candidate region of the HLA1 is equivalent to a 682-kb interval in the genome sequence of N. benthamiana in which three genes probably associated with plant immunity are contained.

The notation for Hla1-1 of respective species in the genus Nicotiana can be tentatively described as, e.g., NsHla1-1 for N. suaveolens, NaHla1-1 for N. africana, and N. tabacum hybrid lethality 1 (NtHL1) for N. tabacum. Thus, it can be representatively argued that deleterious interactions between NsHla1-1 and NtHL1 are the genetic causes of HL in the F1 hybrid between N. suaveolens and N. tabacum (Kawaguchi et al. 2021).

Physiology, biochemistry, and cytology of HL in Nicotiana interspecific F1 hybrid

To delineate the cellular events involved in HL, in vitro cultures prove useful as it is easier to perform cytological observation as well as chemical and other cellular treatments with these systems. Type II lethality of F1 hybrid seedlings was usually suppressed under permissive temperature (35–37 °C), and this was the case for cultured cells derived from cotyledon or hypocotyl tissue of the F1 hybrid seedling grown at the permissive temperature. The suppression of lethality in the hybrid seedlings at permissive temperatures diminished within a very short duration, after moving the plants to a non-permissive temperature (26–28 °C) (Yamada et al. 2000). In addition, the cultured cells maintained at permissive temperatures also started to die after being transferred to non-permissive temperature (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the nature of HL expressed in the seedlings persisted in the cultured cells (Mino et al. 2005).

Physiology and biochemistry of HL could be evidenced in the seedlings, and cultured cells of the F1 hybrids indicated that the processes follow several features of hypersensitive cell death. Certain characteristics of animal apoptosis have been observed in hypersensitive cell death in plants (Morel and Dangl 1997). As it is a molecular and cytological hallmark of apoptotic cell death in animals, generation of oligonucleosomal fragments of DNA (DNA laddering) detected by electrophoresis and TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling assay can be used as a criterion to verify whether an HL complies with apoptosis or programmed cell death (PCD). Genomic DNA laddering in the cells was previously reported in the seedling of the F1 hybrid between N. glutinosa × N. repanda (Marubashi et al. 1999). As these species belong to N. sect. Undulatae and Repandae, respectively, the HL phenotype of seedlings appeared much slower than did the hybrids between species of N. sect. Suaveolentes and N. tabacum. However, this hallmark of PCD was also observed in the quick emergence of HL which was observed in the cells of seedlings and calli of F1 hybrids between N. suaveolens (N. sect. Suaveolentes) and N. tabacum (Yamada et al. 2000). This indicates that the PCD is the fundamental process underlying HL in the interspecific hybrids of Nicotiana.

Generation of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), another biochemical marker of PCD, corroborates the nature of PCD during HL expression. Superoxide anion (O2・-) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were detected in the tissue where type II lethality appeared in the seedlings of the F1 hybrid between N. gossei (N. sect. Suaveolentes) and N. tabacum (Mino et al. 2002). Using the scavengers and inhibitors of ROS, Mino et al. (2004) reported that suppression of H2O2 generation effectively inhibited the progression of type II lethality, whereas suppression of O2・- generation did not, suggesting that H2O2 acted as a more critical signal for HL manifestation than O2・-. This was further supported by a comparison of the two F1 hybrids—N. gossei × rice superoxide dismutase (O2・- scavenger) overexpression N. tabacum line and N. gossei × rice ascorbate peroxidase (H2O2 scavenger) overexpression N. tabacum line. The latter suppressed the progress of type II lethality more efficiently than the former, indicating that H2O2 is causatively linked to HL rather than O2・- (Mino et al. 2004). Using hybrid cultured cells of N. gossei × N. tabacum, Yamamoto et al. (2017) reported that a large quantity of cellular O2・- acts as a suppressor of HL, and this was also the case for nitrogen oxide (NO), another regulatory signaling molecule of PCD. Furthermore, the excess amount of O2・- reduced the cellular concentration of NO, and vice versa, suggesting that the quantitative balance between them plays an important role in the progress of HL. This is attributed to the generation of H2O2 via disproportionation of O2・-, whereby H2O2 cooperatively acts with NO to promote the lethality of F1 hybrids between N. gossei and N. tabacum (Yamamoto et al. 2017).

During the process of HL, PCD-associated gene expression was observed: pathogenesis-related protein 1a and protein inhibitor II were upregulated in the seedlings of N. gossei × N. tabacum (Mino et al. 2002). In addition, elevated expression of multiple genes related to disease resistance was also detected in cultured hybrid cells of N. suaveolens × N. tabacum (Masuda et al. 2007). Contrastingly, the typical phenotype of type II lethality—tissue browning of hypocotyl and root—was provoked by the rapid expression of the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) gene which encodes the rate-limiting enzyme in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Shiragaki et al. 2020). Surprisingly, inhibition of this enzyme suppressed not only the accumulation of phenolic compounds and tissue browning, but also HL in the seedling of N. suaveolens × N. tabacum (Shiragaki et al. 2020). As PAL is thought to be involved in salicylic acid (SA) biosynthesis in plants, it induces plant defense responses via the production of SA (Lefevere et al. 2020). Mino et al. (2006) used cultured cells and seedlings of the F1 hybrid between N. gossei and N. tabacum to demonstrate that mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade played a major role in the cellular signaling pathway provoking HL. In tobacco, two MAPKs—SA-induced protein kinase (SIPK) and wounding-induced protein kinase (WIPK)—were activated by elicitors or following infection with a pathogen (Pedley and Martin 2005). However, SIPK, rather than WIPK, was identified as a mainstream signaling pathway in HL manifestation (Mino et al. 2007a). Interestingly, activation of the MAPK pathway induced not only hypersensitive cell death, but also PAL expression in N. tabacum (Yang et al. 2001). This suggests that the activation of SIPK leading to SA production via the elevation of PAL activity eventually magnifies its signal intensities, forming a positive feedback loop. Consequently, the magnitude of the hypersensitive cell death signal enforced by this loop accelerates HL expression in the hybrid. Thus, inhibition of PAL may eventually suppress the loop acceleration and HL.

Microscopic features of HL in the cultured cells of N. gossei × N. tabacum revealed that the intracellular structure quickly collapsed after transferring from permissive to non-permissive temperature. The disappearance of a cytoplasmic strand, indicating the arrest of cytoplasmic streaming, was observed in the cells within 15 min of transfer. Subsequently, the frequency of cells without membrane boundary of the vacuole started to increase after 3 h, while plasmolysis and cytoplasmic acidification were observed 4 h after the change in temperature (Mino et al. 2005). Formation of knob-like bodies on the tonoplast, small vesicles in the cytoplasm, and the destruction of the tonoplast were observed in the cells of F1 hybrid seedlings grown at the non-permissive temperature, but not at the permissive temperature. Occurrences of those intracellular abnormalities were suppressed by the treatment with caspase-1 inhibitor (Mino et al. 2007b). Caspases are a family of endoproteases—the nexus of the critical regulatory network controlling apoptosis and inflammation—that are involved in maintaining the homeostasis in animal cells (Mcllwain et al. 2013). Although the caspases are absent in plants, caspase-1 like protease—which is functionally equivalent to the caspases—plays an important role in cell death in plants (Woltering 2004). One such protease, vacuolar processing enzyme (VPE), is a plant legumain with significant homology to animal caspase-1 in structure and function that functions as a key factor in tonoplast collapse in the cells of F1 hybrid seedlings of N. gossei × N. tabacum (Mino et al. 2007b). The activities of VPE transiently increased prior to the emergence of the type II lethality phenotype at the non-permissive temperature, whereas those at permissive temperatures remained constant (Mino et al. 2007b). Furthermore, an increase in the transcripts of VPE and its activities at non-permissive temperatures was also observed in the cultured cells of the F1 hybrid of N. suaveolens × N. tabacum (Ueno et al. 2016). The early stage of the cells at non-permissive temperatures revealed macroautophagic-like intracellular structure, increasing the transcripts of autophagy-related genes, accompanied by elevated VPE activities, in contrast to those at permissive temperatures which did not (Ueno et al. 2016). Thus, cellular signaling via the SIPK cascade—which was potentially triggered by deleterious interaction between parental NLR proteins—initiates autophagic responses including the destruction of the tonoplast by elevated VPE activities. The occurrence of the above phenomena in an individual cell of the hybrid plants led to the typical phenotypic feature of type II lethality in the hybrid seedlings.

Does genetic background of the hybrid affect patterns of HL phenotype?

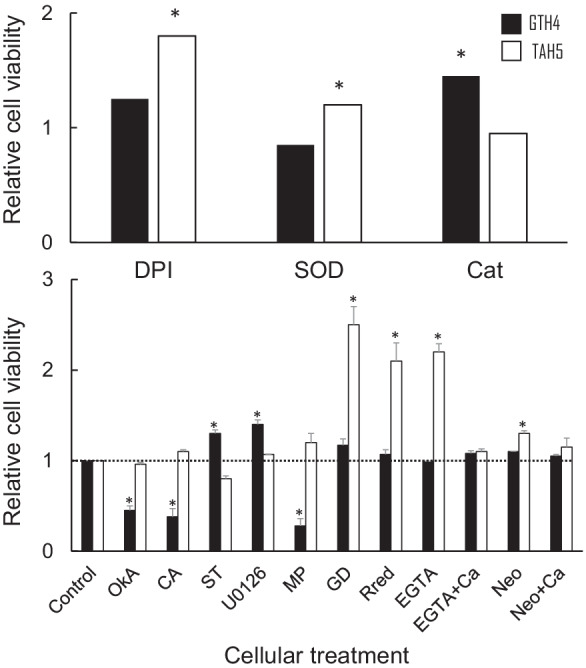

Type II lethality is a typical HL phenotype in the F1 hybrids among species of N. sect. Suaveolentes and N. tabacum. However, details of the HL phenotype vary considerably in the combination of parental species. Nuclear and genomic DNA fragmentation was observed in F1 hybrids of N. suaveolens × N. tabacum (Yamada et al. 2001), while no such typical apoptotic features was observed in F1 hybrids of N. gossei × N. tabacum (Mino et al. 2002; 2005) and N. africana × N. tabacum (unpublished data). In contrast, the rate of initiation and progression of type II lethality differed between the F1 hybrids of N. gossei × N. tabacum (Ng/Nt) and N. tabacum × N. africana (Nt/Na) (Fig. 2A). The Nt/Na hybrid seedlings proceeded to die faster than did the Ng/Nt hybrid seedlings after germination, and the plant growth was eventually arrested earlier in Nt/Na than in Ng/Nt. This difference in the rate of cell death was further verified in cultured cells belonging to the two hybrids. Nt/Na died ca. 1.7 times faster than Ng/Nt after being transferred from permissive to non-permissive temperature (Fig. 2B). In addition, Nt/Na generated more O2・-, while Ng/Nt generated more H2O2 than their respective counterparts at the same time point, following the temperature change (Fig. 2B). Various cellular treatments further clarified the difference in PCD nature between Ng/Nt and Nt/Na (Fig. 3). The scavenger (SOD) and inhibitor (DPI) of O2・- generation effectively suppressed the cell death of Nt/Na, but not that of Ng/Nt, while scavenger of H2O2 (Cat) had little effect on cell death suppression of Nt/Na, but was effective for Ng/Nt. This suggested that O2・- is a more important signaling cue for the initiation of HL in the F1 hybrid of N. tabacum × N. africana (Fig. 3, top panel). However, questions remain regarding the mechanisms underlying the difference in cell death between Ng/Nt and Nt/Na. Do the two hybrids comply with different signaling processes while executing cell death? To answer this question, a pharmacological study would prove useful. Cellular treatments using inhibitors of protein kinase/phosphatase signaling (OkA, CA, ST, U0126) and blocker/promoter of Ca2+ signaling (Gd, Rred, EGTA, NEO, CaCl2), along with an activator of heterotrimeric G proteins (MP), revealed that cellular signaling pathways to initiate HL differed between Ng/Nt and Nt/Na (Fig. 3, bottom panel). As mentioned earlier, SIPK (MAPK) is a major cellular signaling pathway that induces HL in the F1 hybrid seedlings of Ng/Nt, and the effects of inhibitors on protein kinase/phosphatase signaling of the cultured cells confirmed this. However, this was not the case for the F1 hybrid of Nt/Na. In contrast, the role of Ca2+ was more prominent in Nt/Na than in Ng/Nt. Influx of both extracellular (apoplast) and intracellular (endoplasmic reticulum and vacuole) sources of Ca2+ to the cytoplasm was important for the initiation of HL of Nt/Na, but not for Ng/Nt. Since it stimulates the Gα-subunit as a target, MP activates heterotrimeric G protein without the stimulus of an upstream signaling event in both plants and animals (Assmann 2002; Miles et al. 2004). While the number of genes encoding proteins is lower in plants than in animals, heterotrimeric G proteins are involved in disease resistance and apoptotic hypersensitive response in rice (Suharsono et al. 2002) as well as oxidative burst in Arabidopsis (Junghee et al. 2005). Although heterotrimeric G proteins transmit extracellular signals received from cell surface receptors to the plasma membrane Ca2+ channel (Aharon et al. 1998), they also modulate MAPK networks. In fact, the ectopic expression of Gα can stimulate ERK1/2 (a type of MAPK), and MP can activate JNK (another type of MAPK) (Goldsmith and Dhanasekaran 2007). Consequently, MP accelerates cell death of cultured cells of Ng/Nt, which mainly depends on the MAPK signaling pathway, rather than the Ca2+ signaling pathway. In contrast, Ca2+ binding to EF hand motifs and phosphorylation synergistically activates the enzyme activity of the respiratory burst oxidase homolog and promotes ROS generation in Arabidopsis (Ogasawara et al. 2008). Elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ and apoplastic ROS may also activate ROS-activated plasma membrane Ca2+ channels to sustain further Ca2+ influx (Kurusu et al. 2015). This may explain how both Ca2+ and O2・- controlled the initiation and progression of HL in the F1 hybrid of N. tabacum × N. africana. Since the Ca2+ functions as a second messenger in the cell, its signature is decoded by four downstream Ca2+ sensors in plants: the calcineurin B-like proteins, Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), the calmodulins (CaMs), and the calmodulin-like proteins (CMLs) (Sheen 1996; Valmonte et al. 2014; Aldon et al 2018). Although CDPKs positively regulate PCD in plants (Durian et al. 2020; Ren et al. 2021) and MAPK phosphorylation by CDPKs is involved in plant immune responses (Bredow and Monaghan 2019), the Ca2+ signature is also directly transmitted to respective targets via the several pathways; e.g., the activated CaMs by binding Ca2+ interacts with various CaM-binding proteins including transcription factors which are involved in plant defense responses (Reddy et al 2011; Pieterse et al 2012). A similar case is observed with CMLs (Cheval et al 2013). This suggests that some Ca2+ signals are directly transmitted to the target molecule other than protein kinase-mediated pathway. Thus, this may explain the reason why the progress of HL in the F1 hybrid of N. tabacum × N. africana was solely affected by the effects of Ca2+.

Fig. 3.

Effects of cellular treatment on the viability of cultured cells of N. gossei x N. tabacum (GTH4) and N. tabacum x N. africana (TAH4). Percent cell viability of the control group 3 h after the temperature change (37 to 26 °C) was adjusted as 1, and relative viabilities of respective treatments were calculated. Mean values marked with an asterisk differed significantly from control values (1.0) according to the Mann–Whitney U test (a = 0.05) (n = 5). Vertical bars in the bottom figure represent SE. DPI: diphenyleneiodonium (inhibitor of NADPH oxidase), SOD: superoxide dismutase (scavenger of O2・−), Cat: catalase (scavenger of H2O2), Oka: okadaic acid, CA: calyculin A (protein phosphatase inhibitor), ST: staurosporine (protein kinase inhibitor), U0126 (MAPKK inhibitor), MP: mastoparan (G protein activator), GD: gadolinium chloride, Rred: ruthenium red (blocker of calcium ion channel on plasma membrane), EGTA: ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (calcium ion chelator), Neo: neomycine (blocker of calcium influx from endoplasmic reticulum and vacuole to cytoplasm), Ca: calcium chloride (Mino and Shomura, unpublished data). Experimental conditions have been described in the Appendix 2

The variation in the necrotic features of common wheat F1 hybrids among the varieties was due to the presence of multiple necrosis alleles at the Ne1 and Ne2 loci (Hermsen 1963). Furthermore, two types of hybrid necrosis found in F1 hybrids between tetraploid wheat (AABB) and Aegilops tauschii (DD) accessions were controlled by two loci in the D genome—Nec1 (chromosome 7D) and Net2 (chromosome 2D) (Mizuno et al 2010; 2011). Thus, it is conceivable that a combination of parental causal genes resulted in the different lethal phenotypes of the hybrids. However, this finding is not conclusive. The performance of NLR genes—the most common causative factor involved in HI—is prone to be influenced by genetic background, as evidenced by transgenic experiments that revealed that the same rice blast disease–resistant genes confer resistance to one disease-susceptible line of rice but not the other (Wang et al 2019). Taking into consideration that the Hla1-1 interacting with NtHL1 is functionally common among the species in N. sect. Suaveolentes, the variations in the detailed phenotype of type II lethality of respective F1 hybrid combinations (N. tabacum and species in N. sect. Suaveolentes) may be attributed to the differences in the genetic background of each hybrid. Based on the results obtained thus far, autoimmunity signals from deleterious interactions of NLR proteins may be perceived by different sets of receptors and transmitted to respective downstream signal transduction pathways. These circumstances eventually result in varying HL phenotypes in the F1 hybrids of each species combination. Although this is a plausible explanation for the phenotypic variation of type II lethality among the hybrids, the possibility that other causative factors are involved in the processes of HL cannot be ruled out. The following section discusses the possible role of the chaperone complex as the machinery associated with HL in the F1 hybrid of N. gossei × N. tabacum.

The role of chaperone complex in HL expression

Plant NLR protein genes are thought to be involved in hybrid necrosis and lethality in several plant species (refer to the “Plant reproductive isolating barrier” section). Autoimmune responses in the intraspecific F1 hybrid Arabidopsis were observed to result from aberrant interaction of NLR proteins from parental accessions (Uk-1 and Uk-3) (Tran et al. 2017). The interaction of two unlinked NLR loci in the F1 hybrid genome—DM1 from UK-3 and DM2d from UK-1—caused autoimmunity, wherein DM1 acted as the primary signal transducer and DM2d induced DM1 complex activation via heteromerization, with signaling cues inducing HR cell death. Interestingly, Tran et al. (2017) mentioned that the HL phenotype of this hybrid appeared in the wildtype genetic background, but it was almost completely suppressed in the genetic background of eds1-1, rar1-21, or sgt1b. EDS1, a member of the EDS1 protein families, forms a heterodimer with PAD4 (phytoalexin deficient 4) and SAG101 (senescence-associated gene 101) in Arabidopsis, transducing signals from NLR receptors to transcriptional defenses and host plant PCD, indicating that it functions as a downstream node that perceives signals from both the cell surface and intracellular immune receptor systems (Dongus and Parker 2021). In contrast, RAR1 and SGT1 compose the chaperone complex HSP90-SGT1-RAR1, which directly interact with NLR proteins. As they potentially jeopardize the cells by inducing hypersensitive reactions, NLR proteins must be correctly folded and maintained in effector recognition forms in the cells, followed by proper disposal after use to prevent inappropriate cell death signaling (Shirasu 2009). HSP90 functions in conjunction with both SGT1 and RAR1 as co-chaperones to stabilize several plant NLR receptor proteins. Since the inhibition of HSP90 in the chaperone complex impairs resistance against pathogens and reduces the quantity of NLR proteins in cells, it is suggested that NLR proteins are the true clients of the HSP90 chaperone complex (Kadota and Shirasu 2012).

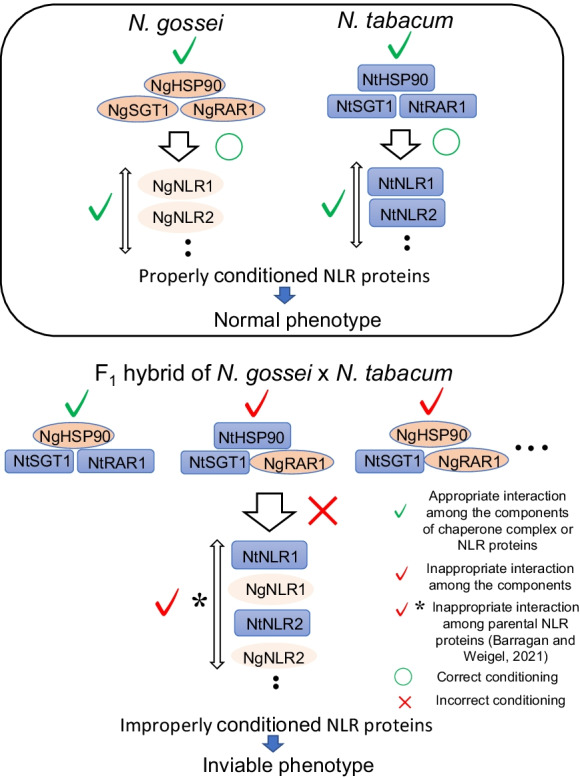

The initiation and progression of death in the cultured cells obtained from the F1 hybrid between N. gossei and N. tabacum was dependent on temperature, but the non-lethal variant cell line lost this characteristic. The former was named GTH4, while the latter is GTH4S (Mino et al. 2006). Since cell death requires de novo expression of genes and protein syntheses, variations in proteomic profiles between the two cell lines were analyzed. Consequently, SGT1 of N. gossei was found to be absent in GTH4S but present in GTH4, while SGT1 of N. tabacum was present in both the cell lines (Katsuyama et al. 2021). SGT1 is a highly conserved and multifunctional protein present in a eukaryote, and its biological functions can be assigned to three distinct domains—namely, TPR, CS, and SGS (Shirasu 2009). The amino acid located at the 5th position in the N terminus of the CS domain—an important region for interacting with HSP90 and RAR1—differed between NtSGT1and NgSGT1: it was glutamate (E) for NtSGT1 but glycine (G) for NgSGT1 (Katsuyama et al. 2021). This amino acid corresponds to E155 and E163 of SGT1a and SGT1b, respectively, of A. thaliana, and negatively charged amino acids (E or D) at this position are generally well conserved in plants. The substitution of this amino acid from E to G slightly affected the interaction between SGT1 and HSP90, but it had little effect on HL, since the amino acid of three species of N. sect. Suaveolentes producing a lethal F1 hybrid by crossing with N. tabacum was E. Although the identity of the amino acid sequence between NtSGT1 and NgSGT1 was very high (97%), transient expression of NgSGT1 in the leaves of N. tabacum provoked a cell death reaction, whereas NtSGT1 did not. A similar case was observed for RAR1, which also demonstrated a high sequence identity (97%) between NtRAR1 and NgRAR1. Moreover, an unfavorable reaction in the cells of N. tabacum was induced by the expression of NgRAR1, whereas NtHSP90, NgHSP90, and NtRAR1 had no such effect. In contrast, a comparison of the effects of simultaneous expression of the combination of three genes (HSP90, SGT1, RAR1) from either parental species on cell death induction revealed that RAR1 in the chaperone complex was found to be a major regulator of downstream signaling events. In any parental combination of HSP90 and SGT1, NtRAR1 as a third component suppressed cell death, but NgRAR1 induced cell death (Katsuyama et al. 2021). It has been proposed that ready-state-matured NLR proteins in cells are processed as per the following steps: (1) the CORD1 domain of RAR1 binds to the ND domain of HSP90 along with ATP; (2) the CORD2 domain of the same RAR1 binds the ND domain of the other HSP90 to maintain the open conformation of the HSP90 dimer; (3) this state then promotes HSP90 dimer interaction with SGT1 and client NLR proteins; (4) once ATP is hydrolyzed in the HSP90 dimer, mature and competent NLR proteins are released from the chaperone complex (Kadota and Shirasu 2012). This scheme predicted that RAR1 dynamically controls conformational changes of the HSP90 dimer and might explain how RAR1, rather than HSP90 and SGT1, affected cell death of N. tabacum via transient expression experiments. To delineate the role of the chaperone complex in the HL of the F1 hybrid, the treatment with geldanamycin (GdA) proved useful. GdA inhibits the function of HSP90 by binding to the N-terminal ATP/ADP-binding pocket (Jhaveri et al. 2012), thus making it more likely to compromise the function of the chaperone complex. Therefore, inhibition of HSP90 will clarify how the chaperone complex works in the process of HL expression. The inhibitor was effective in suppressing the cell death of N. tabacum following the transient expression of three genes containing NgRAR1 and GTH4 after the temperature change, indicating that the chaperone complex plays an important role in determining cell fate, probably via the quality control of NLR proteins (Katsuyama et al. 2021).

Plant NLR proteins have a long co-evolutionary history with pathogens, corresponding to a variety of pathogen effectors that induce disease defense responses (Jones and Dangle 2006). To this end, numerous genes encoding immune receptors with sequence diversity are found in the plant genome (Leister 2004; Baggs et al. 2017), and hence, they should be correctly conditioned to avoid unfavorable reactions in cells. It has been reported that SGT1 and RAR1 in the chaperone complex play an important role in defense against many different pathogens via the specific regulation of respective NLR proteins that induce HR reactions in plants (Shirasu et al. 1999; Tornero et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2010; Xing et al. 2013; Song et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2017). Specificity of the interaction between NLR proteins and the components of the chaperone complex is critical, as the single amino acid substitution in the C-terminal LRR is known to alter RAR1-dependent host signaling (Halterman and Wise 2004). Moreover, overexpression of SGT1—originally obtained from Arachis diogoi—in the leaves of N. tabacum induced HR-like cell death (Kumar and Kirti 2015). Thus, ensuring the correct interaction between the chaperone complex and NLR proteins is necessary for respective evolutionary lineages to maintain resistance specificity to pathogens or to prevent inappropriate cell death signaling. Six orthologs of NLR proteins differ widely between N. tabacum and N. benthamiana, thus ensuring that NLR proteins of each species is adequately controlled by their respective chaperone complex systems. Based on this expectation, cell death patterns in N. benthamiana induced by transient expression of HSP90-SGT1-RAR1 (a mixture of components obtained from both N. tabacum and N. gossei) varied from those in N. tabacum (Katsuyama et al. 2021). The presence of NgRAR1 in any combination with HSP90 and SGT1 correctly induced cell death in N. tabacum, but this effect was not observed in N. benthamiana. Therefore, the chaperone complex that was established in one evolutionary lineage incorrectly modulated NLR proteins belonging to another evolutionary lineage. This suggests that the erroneous interaction of cellular components that induced lethality in hybrids occurs not only among the NLR proteins from the parents, but also among NLR proteins and chaperone complexes that are also mixtures of parental components (Fig. 4). Thus, the possibility of deleterious DM-type epistatic interactions between the chaperone complex and NLR proteins in the hybrid could be considered as another cause of HL.

Fig. 4.

Complicated deleterious relationships between the chaperone complex and NLR proteins in F1 hybrids from N. gossei and N. tabacum. cf. Normal states in parental species (top panel). The scheme was drawn based on the results of Katsuyama et al. (2021)

A possible approach to obtain viable F1 hybrids that are normally lethal

Removing the causative genes from the parents would be the most appropriate way to avert the hybrid problem. Artificial microRNAs (amiRNAs) that inactivate NB-LRR genes in the DM1 region of A. thaliana strain Uk-3 successfully recovered phenotypically normal F1 hybrids by crossing with Uk-1, while amiRNAs for other genes in this region had no effect on suppressing the necrotic features of the F1 hybrids (Bomblies et al. 2007). Furthermore, Deng et al. (2019) reported that silencing the CC-NBS-LRR genes via VIGS restored the normal phenotype in the leaves of the F1 hybrid between Gossypium barbadense and G. hirsutum, which usually exhibits a lethal necrotic spot in the leaves. Similarly, CRISPR-Cas9–based gene editing effectively suppressed the HL phenotype in the F1 hybrids between eight species of N. sect. Suaveolentes and N. tabacum by introducing frameshift mutation into Nt6549g30 (NLR gene) in N. tabacum (Ma et al. 2020). The role of the plant immune system in HL has been expounded in several important crop species (refer to the “Plant reproductive isolating barrier” section). Although no direct evidence was presented, involvement of autoimmunity was also expected in the HL occurring in the hybrid between tetraploid wheat and Aegilops tauschii, as several defense-related genes were upregulated in the hybrid (Mizuno et al. 2010). Bomblies and Weigel (2007) proposed that selection pressure introduced via the plant breeding programs for disease resistance might possibly increase the chance of deleterious epistatic interaction in the hybrids between crop cultivars and their counterparts. If this is the case, any autoimmune-type HL observed in the hybrids from wide hybridization may be attributable to NLR genes. However, the number of NLR genes in the plant genome is generally quite high, functionally redundant, and variable (Wu et al. 2017; Barragan and Weigel 2021). Consequently, searching for the causative NLR genes involved in HL is time-consuming and will be difficult unless proper genetic molecular makers are available for the plants.

Taking into consideration that the causative factors of HL can be restricted to NLR genes, it is worthwhile to suppress the function of individual components of the chaperone complex (HSP90-SGT1-RAR1). As a steady-state accumulation of NLR proteins and the resistance against pathogens requires the action of RAR1 (Muskett et al. 2002; Hann and Rathjen 2007) as well as SGT1 (Mestre and Baulcombe 2006; Botër et al. 2007), malfunction of these components in the chaperone complex reduces the cellular NLR proteins below the threshold concentrations required to provoke HR. This is the reason why hybrid necrosis in Arabidopsis was suppressed in the genetic background of rar1-21 or sgt1b (Tran et al., 2017). The number of isoforms of SGT1 and RAR1 is generally low. For instance, two in Arabidopsis (Austin et al. 2002) and three in wheat (Wang et al. 2015) as well as peanut (Yuan et al. 2021) have been identified for SGT1, while for RAR1, one each have been identified in peanut (Yuan et al. 2021), barley (Azevedo et al. 2002), Arabidopsis (Muskett et al. 2002), and potato (Bhaskar et al. 2008), along with two in common tobacco (Katsuyama et al. 2021). In addition, since the sequence of functional domains in respective protein genes is highly conserved in plants, the basic design and construction of the vector that induces loss of function mutation in SGT1 and RAR1 will be widely applicable to several different crop species. However, the crucial role played by SGT1 in growth and development (Azevedo et al. 2006; Gray et al. 2003) suggests that knockout of all copies of SGT1 should be avoided. In contrast, RAR1 is required for disease resistance in plants (Warren et al. 1999; Tornero et al. 2002; Staal et al. 2006), but its null mutation does not affect any plant growth (Takahashi et al. 2003). Thus, it is worth exploring the development of a null mutant of RAR1 for both parents, to minimize the appearance of a lethal F1 hybrid during hybridization.

Concluding remarks

Instances of HI abound in both plants and animals (Coyne and Orr 2004). Reproductive isolation barriers including HI play an important role in speciation and can contribute to the generation of biodiversity in nature. In contrast, HI is a major drawback to the wide hybridization and introgression breeding program of plants which contributes to the development of novel genotypes with stronger tolerance to biotic or abiotic stresses than conventional cultivars. Circumventing HI in the breeding program is a pressing need for facilitating the sustenance of agriculture in the near future. The involvement of the plant immune system in the HI of plant hybrids is supported by the evidence of cellular events, biochemical and physiological reactions in hybrid cells, as well as the identification and characterization of causative genes. Thus, to address the agenda, induced null mutation and/or silencing of NLR genes might be effective in suppressing the HL of F1 hybrids (Bomblies et al. 2007; Deng et al. 2019; Ma et al. 2020). Another possibility is to inhibit the function of genes in the chaperone complex. Both SGT1 and RAR1, especially the latter, are available targets for gene editing to prepare null mutants of the parents who are expected to provide the viable F1 hybrids. As the respective components in the chaperone complex are indispensable to providing resistance against many kinds of baneful pathogens (refer to the “The role of chaperone complex in HL expression” section), nullifying their functions seems to be inappropriate to confer disease resistance to hybrid progenies. However, these F1 hybrids do not become commercial cultivars, per se, as they are usually sterile and contain undesired traits of wild relatives that are unsuitable for commercial cultivation. They must be further improved upon by crossing with elite cultivars and successive selection processes and hence ensuring that the function of the chaperone complex and disease resistance can be progressively restored in the progenies. The lines with various helpful traits selected from these progenies are expected to become novel elite cultivars for near-future crop production.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Mr. Takumi Yamamoto for his contribution to collect a part of the data in Fig. 3. This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Abbreviations

- CAPS

Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence

- CHORD1and 2

Cysteine- and histidine-rich domain 1 and 2

- CRISPR-Cas9

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-Cas9

- CS

CHORD-containing protein and SGT1 domain

- EDS1

Enhanced disease susceptibility 1

- HSP90

Heat shock protein 90

- NB-LRR protein

Nucleotide-binding site and leucine-rich repeat protein

- NLR protein

NB and LRR–containing protein

- ND

Nucleotide-binding domain

- RAR1

Required for Mla 12 resistance

- SGS

SGT1-specific domain

- SGT1

Suppressor of G2 allele of Skp1

- SSR

Simple sequence repeats

- TPR

Tetratricopeptide repeat

- VIGS

Virus-induced gene silencing

Appendix 1

Table 1

Table 1.

Phenotypes of five lethality observed in interspecific F1 hybrid of genus Nicotiana

| Lethality type | Phenotype | Representative cross combination |

|---|---|---|

| Type I* | Browning of shoot apex and root tip | N. nudicaulis × N. tabacum |

| Type II*: | Browning of hypocotyl and root | N. debneyi × N. tabacum |

| Type III*: | Yellowing of true leaf | N. paniculate × N. nudicaulis |

| Type IV*: | Multiple shoot formation | N. paniculate × N. glutinosa |

| Type V**: | Fading shoot color | N. tabacum × N. occidentalis |

*, Yamada T et al. (1999) Breed Sci 49:203–210;

**, Tezuka T, Marubashi W (2012) PLoS ONE 7(4): e36204

Appendix 2

-

Cell culture and determination of cell viability

After 3 to 4 days of subculture in fresh liquid medium, the cells were transferred to 26 ºC or 37 ºC, and their viability was determined by a previously reported method (Mino et al. 2005).

-

Cellular treatment

The pharmacological treatments of the cells were performed 0.5 h before transferring the cells from 37 ºC to 26 ºC. Cell viability was determined 3 h following the temperature shift. Moreover, to explore the effects of calcium ion (Ca2+), the cells were cultured for 10 days in the calcium-free medium to reduce intracellular Ca2+ concentration. The concentration of each reagent treatment was as follows: okadaic acid (OkA), 0.1 μM; calyculin A (CA), 0.1 μM; staurospolin (ST), 1 μM; U0126, 100 μM; mastoparan (MP), 5 μM; gadolinium chloride (GD), 5 μM; ruthenium red (Rred), 50 mM; ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1 mM; CaCl2 (Ca), 1 mM; and neomycine (Neo), 100 μM.

-

Statistics

The percentage data were transformed into arcsine values to calculate the standard error (SE) of the mean. Differences between the means were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test at a 5% level of significance.

Mino M et al. (2005) Plant Cell Rep 24:179–188.

Author contribution

Masanobu Mino, the corresponding author, certifies that all authors have participated sufficiently in preparing the manuscript. Masanobu Mino gave the basic idea for the article, performed the literature search, wrote manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Takahiro Tezuka proposed ideas for improving the quality of the article and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Sachiko Shomura performed the experiments, collected and analyzed the data in Figs. 2 and 3, and reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aharon GS, Gelli A, Snedden WA, Blumwald E. Activation of a plant plasma membrane Ca2+ channel by TGalpha 1, a heterotrimeric G protein alpha-subunit homologue. FEBS Lett. 1998;424:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldon D, Mbengue M, Mazars C, Galaud J-P (2018) Calcium signalling in plant biotic interactions. Int J Mol Sci 19, 665; 10.3390/ijms19030665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Assmann SM. Heterotrimeric and unconventional GTP binding proteins in plant cell signaling. Plant Cell. 2002;12:S355–S373. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MJ, Muskett P, Kahn K, Feys BJ, Jones JDG, Parker JE. Regulatory role of SGT1 in early R gene-mediated plant defenses. Science. 2002;295:2077–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.1067747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo C, Sadanandom A, Kitagawa K, Freialdenhoven A, Shirasu K, Schulze-Lefert P. The RAR1 interactor SGT1, an essential component of R gene-triggered disease resistance. Science. 2002;295:2073–2076. doi: 10.1126/science.1067554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo C, Betsuyaku S, Peart J, Takahashi A, Noël L, Sadanandom A, Casais C, Parker J, Shirasu K. Role of SGT1 in resistance protein accumulation in plant immunity. EMBO J. 2006;3:2007–1016. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baack E, Melo MC, Rieseberg LH, Ortiz-Barrientos D. The origins of reproductive isolation in plants. New Phytol. 2015;207:968–984. doi: 10.1111/nph.13424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek YS, Covey PA, Petersen JJ, Chetelat RT, McClure B, Bedinger PA. Testing the SI x SC rule: pollen-pistil interaction in interspecific crosses between members of the tomato clade (Solanum section Lycopersicon. Solanaceae) Am J Bot. 2015;102:302–311. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggs E, Dagdas G, Krasileva KV. NLR diversity, helpers and integrated domains: making sense of the NLR identity. Curr Opi Plant Biol. 2017;38:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barragan AC, Weigel D. Plant NLR diversity: the known unknowns of pan-NLRomes. Plant Cell. 2021;33:814–831. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koaa002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso MF, Arraes FBM, Grossi-de-Sa M, Moreira VJV, Alves-Ferreira M, Grossi-de-Sa MF. Insight into genetic and molecular elements for transgenic crop development. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:509. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbeć A, Doroszewska T (2020) The use of Nicotiana species in tobacco improvement. In: Ivanov NV, Sierro N, Peitsch MC (eds) The Tobacco Plant Genome, Compendium of Plant Genomes, Springer-Verlag, pp 101–146. 10.1007/978-3-030-29493-9

- Bhaskar PB, Raasch JA, Kramer LC, Neumann P, Weilgus SM, Austin-Phillips S, Jiang J. SgtI, but not RarI, is essential for the RB-medicated broad-spectrum resistance to potato late blight. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229/8/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindler G, Plieske J, Bakaher N, Gunduz I, Ivanov N, Van der Hoeven R, Ganal M, Donini P. A high density genetic map of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) obtained from large scale microsatellite maker development. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:219–230. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1578-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomblies K, Lempe J, Epple P, Warthmann N, Lanz C, Dangl JL, Weigel D. Autoimmune response as a mechanism for a Dobzhansky-Muller-type incompatibility syndrome in plants. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(9):2236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbil.0050236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomblies K, Weigel D (2007) Hybrid necrosis: autoimmunity as a potential gene-flow barrier in plant species. Nat Rev Genet 8:382–393. 10/1038/nrg2082 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bomlies K. Doomed lovers: mechanism of isolation and incompatibility in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:109–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botër M, Amigues B, Peart J, Breuer C, Kadota Y, Casais C, Moore G, Kleanthous C, Ochsenbein F, Shirasu K, Guerois R. Structural and functional analysis of SGT1 reveals that it interaction with HSP90 is required for the accumulation of Rx, and R protein involved in plant immunity. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3791–3804. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredow M, Monaghan J. Regulation of plant immune signaling by calcium-dependent protein kinases. MPMI. 2019;32:6–19. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-18-0267-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz AK, Bedinger PA. Pollen-pistil interactions as reproductive barriers. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2021;72:615–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-080620-102159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Baltanás V, Wang J, Chae E. Hybrid incompatibility of the plat immune system: an opposite force to heterosis equilibrating hybrid performances. Front Plant Sci. 2021;11:576796. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.576796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase MW, Christenhusz MJM, Conran JG, Dodsworth S, de Assis FNM, Felix LP, Fay MF. Unexpected diversity of Australian tobacco species (Nicotiana section Suaveolentes, Solanaceae) Curtis’s Bot Magaz. 2018;35:212–227. doi: 10.1111/curt.12241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen H, Lin Y-S, Shen J-B, Shan J-X, Qi P, Shi M, Zhu M-A, Huang X-H, Feng Q, Han B, Jiang L, Gao J-P, Lin H-X. A two-locus interaction causes interspecific hybrid weakness in rice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhao Z, Liu L, Kong W, Lin Y, You S, Bai W, Xiao Y, Zheng H, Jiang L, Li J, Zhou J, Tao D, Wan J. Genetic analysis of a hybrid sterility gene that causes both pollen and embryo sac sterility in hybrid between Oryza sativa L. and Oryza longistaminata. Heredity. 2017;119:166–173. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2017.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ding J, Ouyang Y, Du H, Yang J, Cheng K, Zhao J, Qui S, Zhang S, Yao J, Liu K, Wang L, Xu C, Li X, Xue Y, Xia M, Ji Q, Lu J, Xu M, Zhang Q. A triallelic system of S5 is a major regulator of the reproductive barrier and compatibility of indica-japonica hybrid in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11436–11441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval C, Aldon D, Galaud J-P, Ranty B. Calcium/calmodulin-mediated regulation of plant immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:1766–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M-Y, Chung J-D, Ramanna M, van Tuyl JM, Lim K-B (2013) Production of polyploids and unreduced gametes in Lillum auratum × L. henryi hybrid. Int J Biol Sci 9:693–701. https://www.ijbs.com/v09p0693.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clarkson JJ, Dodsworth S, Chase MW. Time-calibrated phylogenetic trees establish a lag between polyploidization and diversification in Nicotiana (Solanaceae) Plant Syst Evol. 2017;303:1001–1012. doi: 10.1007/s00606-017-1416-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA, Orr A (2004) Speciation. Sinauer Associates, Inc. Massachusetts U.S.A

- Deng J, Fang L, Zhu X, Zhou B, Zhang T. A CC-NBS-LRR gene induces hybrid lethality in cotton. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:5145–5156. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVerna JW, Myers JR, Collins GB. Bypassing prefertilization barriers to hybridization in Nicotiana using in vitro pollination and fertilization. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;73:665–671. doi: 10.1007/BF00260773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongus JA, Parker JE. EDS1 signalling: at the nexus of intracellular and surface receptor immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2021;62:102039. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durian G, Sedaghatmehr M, Matallana-Rmirex LP, Schilling SM, Schaepe S, Guerra T, Herde M, Whitte C-P, Mueller-Roeber B, Schulze WX, Balazadeh S, Romeis T. Calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK1 controls cell death by in vivo phosphorylation of senescence master regulator ORE1. Plant Cell. 2020;32:1610–1625. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nation (2011) Current status and options for crop biotechnologies in developing countries. Chapter 1 in proceedings of the FAO international technical conference on “Biotechnologies for agricultural development”. ISBN 978–92–5–106906–6

- Filler DM, Luby JJ, Ascher PD. Incongruity in the interspecific crosses of Vitis L. Morphological abnormalities in the F2 progeny. Euphytica. 1994;78:227–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00027521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman L, Sweigart AL. When two rights make a wrong: the evolutionary genetics of plant hybrid incompatibilites. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018;69:701–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Rueda AM, Paris M, Schmidt A, Widmer A, Grossniklaus U, Städler T. Genomic inprinting in the endosperm is systematically perturbed in abortive hybrid tomato seeds. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:2935–2946. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S, Tsuchimatu T, Kimura Y, Ishida S, Tangpranomkorn S, Shimosato-Asano H, Iwano M, Furukawa S, Itoyama W, Wada Y, Shimizu KK, Takayama S. A stigmatic gene confers interspecies incompatibility in the Brassicaceae. Nature Plants. 2019;5:731–741. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel DU, Burns JA, Burk LG. Interspecific hybridization with an African tobacco, Nicotiana africana Merxm. J Here. 1979;70:342–344. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith ZG, Dhanasekaran DN. G protein regulation of MAPK networks. Oncogene. 2007;26:3122–3142. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray WM, Muskett PR, Chunag H-W, Parker JE. Arabidopsis SGT1b protein is required for SCFTIR1-mediated auxin response. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1310–1319. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halterman DA, Wise RP. A single-amino acid substitution in the sixth leucine-rich repeat of barley MLA6 and MLA13 alleviates dependence of RAR1 for disease resistance signaling. Plant J. 2004;38:215–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock WG, Kuraparthy V, Kernodle SP, Lewis RS (2015) Identification of maternal haploids of Nicotiana tabacum aided by transgenic expression of green fluorescent protein: evidence for chromosome elimination in the N. tabacum × N. africana interspecific cross. Mol Breed 35:179. 10.1007/s11032-015-0372-8

- Hann DR, Rathjen JP (2007) Early events in the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas syringae on Nictiana benthamiana. Plant J 49:607–618. 10.111/j.1365-313X.2006.02981.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hermsen JGTH. Hybrid necrosis as a problem for the wheat breeder. Euphytica. 1963;12:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00033587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hondnett GL, Burson BL, Rooney WL, Dillon SL, Price HJ. Pollen-Pistil Interaction Result in Reproductive Isolation between Sorghum Bicolor and Divergent Sorghum. Species. 2005;45:1403–1409. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2004.0429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez MS, Camadro EL. Reproductive behavior of the wild carrots Daucus pusillus and Daucus montanus from Argentina. Botany. 2015;93:279–286. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2014-0243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka T, Kuboyama T, Marubashi W, Oda M, Tezuka T. Nicotiana debneyi has a single dominant gene causing hybrid lethality in crosses with N. tabacum. Euphytica. 2012;186:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0570-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue E, Marubashi W, Niwa M. Genomic factors controlling the lethality exhibited in the hybrid between Nicotiana suaveolens Lehm. and N. tabacum L. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93:341–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00223174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeuken MJW, Zhang NW, McHale L, Pelgrom K, den Boer E, Lindhout P, Michelmore RW, Visser RGF, Niks R. Rin4 causes hybrid necrosis and race-specific resistance in an interspecific lettuce hybrid. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3368–3378. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhaveri K, Taldone T, Modi S, Chiosis G. Advances in the clinical development of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) inhibitors in cancers. Biochimi Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:742–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JDG, Dangle JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junghee HJ, Wang S, Chen JG, Jones AM, Fedoroff NV. Different signaling and cell death roles of heterotrimeric G protein a and b subunits in the Arabidopsis oxidative stress response to ozone. Plant Cell. 2005;17:957–970. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota Y, Shirasu K. The HSP90 complex of plants. Biochimi Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:689–697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa F (1957) Crop breeding based on the interspecific and intergeneric hybridization (Japanese title to English translation). in Japanese, Sangyo Tosho Co. Ltd

- Katsuyama Y, Doi M, Shioya S, Hane S, Yoshioka M, Date S, Miyahara C, Ogawa T, Takada R, Okumura H, Ikusawa R, Kitajima S, Oda K, Sato K, Tanaka Y, Tezuka T, Mino M (2021) The role of chaperone complex HSP90-SGT1-RAR19 as the associated machinery for hybrid inviability between Nicotiana gossei Domin and N. tabacum L. Gene 776:145443. 10.1016/j.gene.2021.145443 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi K, Ohya Y, Maekawa M, Iizuka T, Hasegawa A, Shiragaki K, He H, Oda M, Morikawa T, Yokoi S, Tezuka T (2021) Two Nicotiana occidentalis accessions enable gene identification for type II hybrid lethality by the cross to N. sylvestris. Sci Rep 11:17093. 10.1038/s41598-021-96482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kelly LJ, Leitch AR, Clarkson JJ, Knapp S, Chase MW. Reconstructing the complex evolutionary origin of wild allopolyploid tobacco (Nicotiana section Suaveolentes) Evolution. 2012;67:80–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermicle JL. A selfish gene governing pollen-pistil compatibility confers reproductive isolation between maize relatives. Genet. 2006;172:499–506. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.048645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori S, Masuda Y, Marubashi W. Heat treatment temporarily suppresses expression of programmed cell death in hybrid tobacco cells (Nicotiana suaveolens x N. tabacum) expressing hybrid lethality. Plant Biotec. 2005;22:345–348. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.22.345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger J, Thomas CM, Golstein C, Dixon S, Smoker M, Tang S, Mulder L, Jones JDG. A tomato cysteine protease required for Cf-2-dependent disease resistance and suppression of autonecrosis. Science. 2002;296:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.1069288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Kirti PB. Pathogen-induced SGT1 of Arachis diogoi induces cell death and enhanced disease resistance in tobacco and peanut. Plant Biotech J. 2015;13:73–84. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurusu T, Kuchitsu K, Tada Y. Plant signaling networks involving Ca2+ and Rboh/Nox-mediated ROS production under salinity stress. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:427. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafon-Placette C, Johannessen IM, Hornslien KS, Ali MF, Bjerkan KN, Bramsiepe J, Glöckle BM, Rebernig CA, Brysting AK, Grini P, Köhler C (2017) Endosperm-based hybridization barriers explain the pattern of gene flow between Arabidopsis lyrate and Arabidopsis arenosa in central Europe. Proc Ntl Acd Sci USA 114:E1027-E1035. https://www.pnas.org/content/114/6/E1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lefevere H, Bauters L, Gheysen G. Salicylic acid biosynthesis in plants. Frot Plant Sci. 2020;11:228. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leister D. Tandem and segmental gene duplication and recombination in the evolution of plant resistance gene. Trend Genet. 2004;20:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Chen L, Jiang L, Zhu S, Zhao Z, Liu S, Su N, Zhai H, Ikehashi H, Wan J (2007) Fine mapping of S32(t), a new gene causing hybrid embryo sac sterility in a Chinese landrace rice (Oryza sativa L.) Theor Appl Genet 114:515–524. 10.1007/s00122-006-0450-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zhou J, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Pu Q, Tao D. New insights into the nature of interspecific hybrid sterility in rice. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:555572. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.555572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liu B, Deng S, Zhao H, Li H, Xing S, Fetzer DD, Li M, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB, Liu P. Evolution of interspecies unilateral incompatibility in relatives of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:2742–2753. doi: 10.1111/mec.14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Hokin SA, Kermicle JL, Hartwig T, Evans MM. A pistil-expressed pectin methylesterase confers cross-incompatibility between strains of Zea mays. Nature Commun. 2019;10:2304. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10259-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Hancock WG, Nifong JM, Kernodle SP, Lewis RS. Identification and editing of a hybrid lethality gene expands the range of interspecific hybridization potential in Nicotiana. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:2915–2925. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcellán ON, Camadro EL. Self- and cross-incompatibility in Asparagus officinalis and Asparagus densiflorus cv. Sprengeri Can J Bot. 1996;74:1621–1625. doi: 10.1139/b96-196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marubashi W, Yamada T, Niwa M. Apoptosis detected in hybrids between Nicotiana glutinosa and N. repanda expressing lethality. Planta. 1999;210:168–171. doi: 10.1007/s004250050667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubashi W, Onosato K. Q chromosome controls the lethality of interspecific hybrids between Nicotiana tabacum and N. suaveolens. Breed Sci. 2002;52:137–142. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.52.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marubashi W, Kobayashi M. Temperature-dependent apoptosis detected in the hybrid between Nicotiana debneyi and N. tabacum expressing lethality. Plant Biotec. 2002;19:267–270. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.19.267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y, Yamada T, Marubashi W. Time course analysis of apoptosis during hybrid lethality in tobacco hybrid cell (Nicotiana suaveolens x N. tabacum) Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:420–427. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda Y, Yamada T, Kuboyama T, Marubashi W. Identification and characterization of gene involved in hybrid lethality in hybrid tobacco cells (Nicotiana suaveolens × N. tabacum) using suppression subtractive hybridization. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:1595–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maune JF, Camadro EL, Erazzú LE. Cross-incompatibility and self-incompatibility: unrelated phenomena in wild and cultivated potatoes? Botany. 2018;96:33–45. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2017-0070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcllwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;3(5):a008656. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo MC, Grealy A, Brittain B, Walter GM, Ortiz-Barrientos D. Strong extrinsic reproductive isolation between parapatric populations of an Australian groundsel. New Phytol. 2014;203:323–334. doi: 10.1111/nph.12779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergoum M, Sapkota S, ElDoliefy AEA, Naraghi, SM, Pirseyedi S, Alamri SM, AbuHammad W (2019) Triticale (x Triticosecale Wittmarck) breeding. In: Al-Khayri JM, Jain M, Johnson DV (Eds) Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Cereals. Springer Verlag. Chapter 11 pp405–451

- Mestre P, Baulcombe DC. Elicitor-medicated oligomerization of the tobacco N disease resistance protein. Plant Cell. 2006;18:491–501. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]