Abstract

In an endeavor to identify small molecules for the management of non-small-cell lung carcinoma, 10 new hydrazone derivatives (3a–j) were synthesized. MTT test was conducted to examine their cytotoxic activities against human lung adenocarcinoma (A549) and mouse embryonic fibroblast (L929) cells. Compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3i were determined as selective antitumor agents on A549 cell line. Further studies were conducted to figure out their mode of action. Compounds 3a and 3g markedly induced apoptosis in A549 cells. However, both compounds did not show any significant inhibitory effect on Akt. On the other hand, in vitro experiments suggest that compounds 3e and 3i are potential anti-NSCLC agents acting through Akt inhibition. Furthermore, molecular docking studies revealed a unique binding mode for compound 3i (the strongest Akt inhibitor in this series), which interacts with both hinge region and acidic pocket of Akt2. However, it is understood that compounds 3a and 3g exert their cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on A549 cells via different pathway(s).

1. Introduction

Cancer remains a deadly global health concern with more than 200 different types, affecting over 60 human organs.1 Among all cancers, lung cancer is the primary cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality in males, while, in females, it ranks second for mortality, after breast cancer, and third for incidence, after breast and colorectal cancer.2 The disease is notorious for its exceptional potency to spread to distant parts of the body (metastasis), as well as its ability to progress rapidly in its early stages.3

There are two groups of lung cancer, namely, small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).1 85% of lung cancer cases are attributed to NSCLC.4

Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy are currently available approaches for NSCLC therapy.5 The best treatment strategy for patients with early-stage NSCLC is still surgical intervention. However, surgery is no longer an option for patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC.6,7 Major treatment approaches for unresectable NSCLC are chemotherapy and radiotherapy.7 Platinum-based chemotherapeutics, taxanes, and other chemotherapeutics (e.g., vinorelbine, gemcitabine, and pemetrexed) are used either alone or in combination.5 Despite their benefits in NSCLC therapy, these chemotherapeutics damage healthy cells as well as cancer cells and therefore they cause severe adverse effects and toxicity.8 Resistance to radio(chemo)therapy is also a significant barrier to NSCLC therapy resulting in tumor recurrence and disease progression.9 The current challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC lead to poor prognosis and low survival rate.10

Akt belongs to the family of serine/threonine-specific protein kinases essential for regulating crucial cellular processes including cell survival, proliferation, growth, apoptosis, and glucose metabolism. The abnormal overexpression or activation of Akt is involved in a variety of human malignancies and therefore inhibiting Akt has emerged as a pivotal strategy for the treatment of various types of cancer, particularly B-cell malignancies, NSCLC, and breast cancer.11−13 Despite the large number of Akt inhibitors developed to date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved any Akt inhibitors yet.11

Hydrazides-hydrazones are frequently occurring eligible motifs in druglike small molecules due to their distinctive characteristics and several pharmaceutical applications for the treatment of many diseases, particularly severe bacterial infections, cancer, and inflammation.14−18 Hydrazones have been reported to exert striking antitumor action via induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, inhibition of angiogenesis, and a plethora of cancer-related biological targets (e.g., Akt).19−26

Benzoxazoles are privileged building blocks for the synthesis of biologically active ligands targeting a plethora of crucial targets/pathways due to their unique features allowing them to effectively bind to diverse biological targets with distinct affinities.27−31 Several studies have revealed that benzoxazoles exert marked cytotoxic activity against a variety of cancer cell lines through diverse mechanisms including induction of apoptosis, inhibition of Akt phosphorylation, and so on.32−39

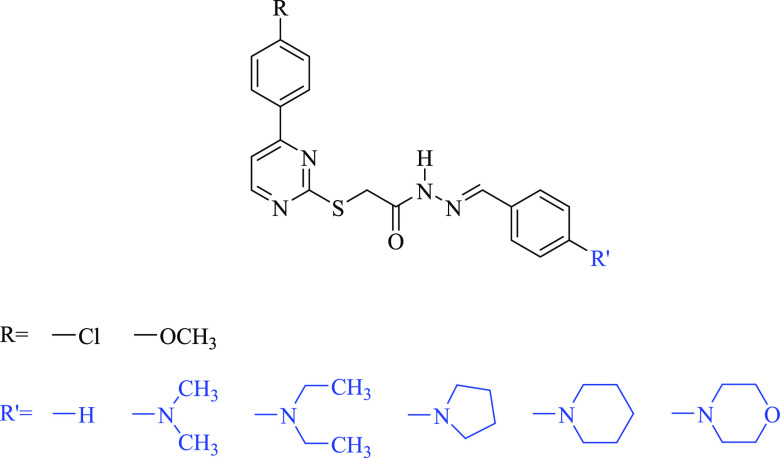

The publications related to hydrazones19−26 and benzoxazoles32−39 exerting pronounced anticancer activity through inhibition of target enzymes involved in the pathogenesis of lung cancer motivated us to design novel anti-NSCLC agents by means of the molecular hybridization of the benzoxazole core with the hydrazide group, which was conjugated with the benzylidene moiety substituted at the para position with dialkylamino groups (dimethylamino, diethylamino), nitrogen-containing electron-withdrawing groups (nitro substituent), five- (pyrrolidine) or six-membered heterocyclic motifs (piperidine, morpholine and piperazine), heteroaromatic rings (imidazole, triazole) based on our previous work (Figure 1),21 and the structure–activity relationships of existing Akt inhibitors11 together with the bioisosteric replacement. In this context, the designed compounds were synthesized readily and assessed for their cytotoxic properties on human lung adenocarcinoma (A549) and mouse embryonic fibroblast (L929) cells. In vitro experimental studies were carried out for promising anti-NSCLC agents to shed light on their mechanism of action.

Figure 1.

Pyrimidine-based hydrazones reported previously as anticancer agents by our research team.21

2. Results and Discussion

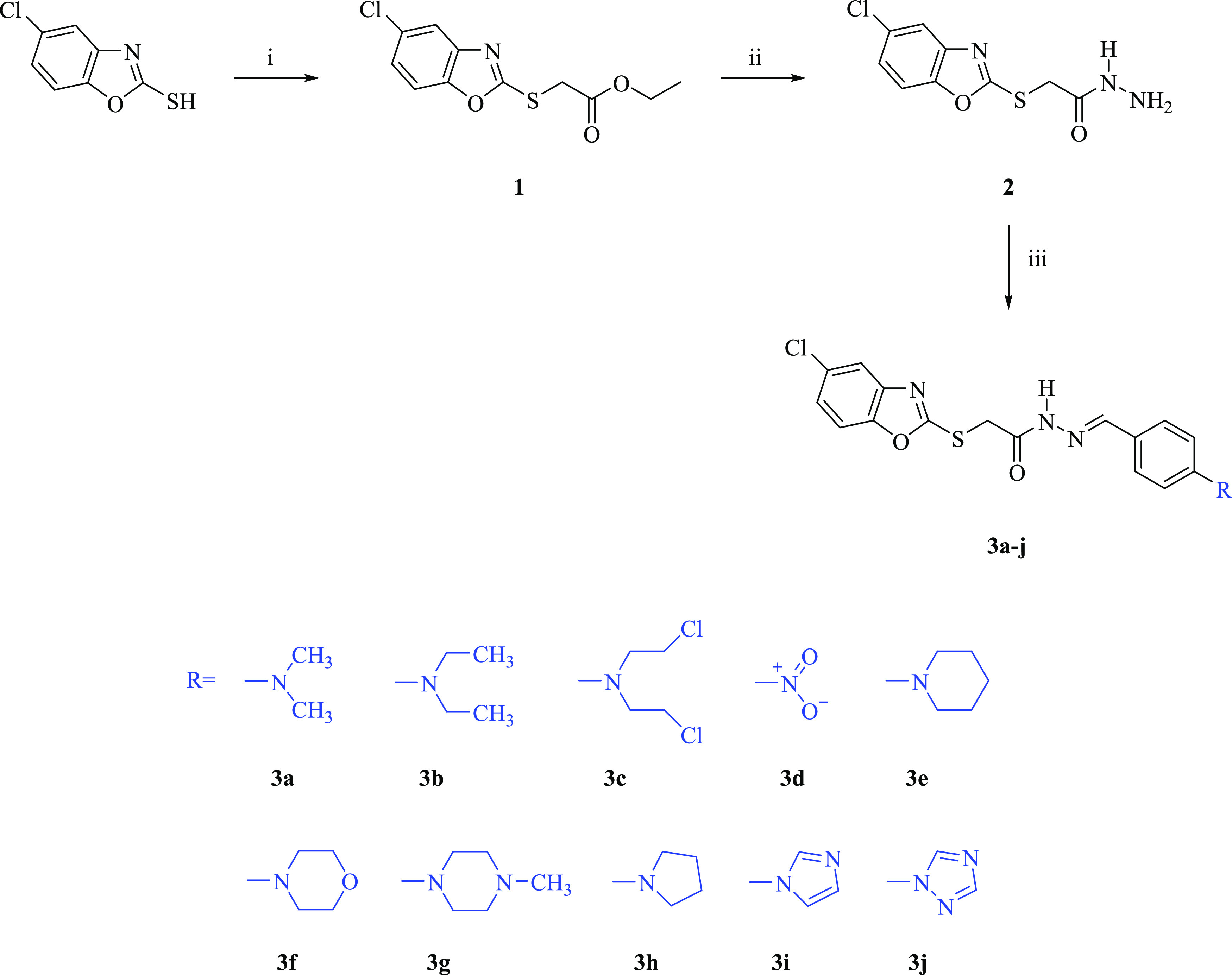

2.1. Chemistry

The hitherto unreported hydrazones (3a–j) were prepared as depicted in Scheme 1. The base-catalyzed reaction of 5-chloro-2-mercaptobenzoxazole with ethyl chloroacetate yielded ethyl 2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetate (1), which subsequently underwent a reaction with hydrazine hydrate affording the corresponding hydrazide (2). Finally, compound 2 was reacted with 4-substituted benzaldehydes to obtain compounds 3a–j. Infrared (IR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR, 1H and 13C), and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) were used to verify their chemical structures. These spectra are provided in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 3a–j.

(i) ClCH2COOEt, K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 10 h; (ii) NH2NH2.H2O, ethanol, stirring at room temperature, 5 h; (iii) ArCHO, ethanol, reflux, 8 h.

In the IR spectra of compounds 3a–j, the N–H stretching band of the hydrazone group was detected at 3207.62–3159.40 cm–1, while the C=O stretching band was detected at 1705.07–1654.92 cm–1. In the 1H NMR spectra of compounds 3a–j, S-CH2 protons gave rise to two singlets in the range of 4.25–4.73 ppm. The peaks at 11.47–12.09 ppm were attributed to the N–H proton of the hydrazone moiety, while the peaks in the region 7.88–8.26 ppm were assigned to the CH=N proton. In the 13C NMR spectra of compounds 3a–j, the S-CH2 carbon gave rise to a singlet in the region 34.76–35.02 ppm. The signals due to the CH=N and the C=O carbons were detected in the range of 142.95–145.19 ppm and 167.08–168.27 ppm, respectively. In all HRMS spectra, the predicted and measured m/z values for [M + H]+ were consistent with each other.

2.2. Biochemistry

The hydrazide (2) and the hydrazones (3a–j) were assessed for their cytotoxic features on A549 human lung adenocarcinoma and L929 mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. The IC50 values of the compounds are presented in Table 1. Compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3i showed cytotoxic effects on A549 cells with IC50 values of 91.35 ± 21.89, 176.23 ± 56.50, 46.60 ± 6.15, and 83.59 ± 7.30 μM, respectively. The selectivity index (SI) values of compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3i were found as >5.47, >2.84, 5.94, and >5.98, respectively. It can be concluded that these agents exert cytotoxic activity against A549 cells without influencing normal (L929) cells at their effective doses.

Table 1. IC50 and SI Data for Compounds 2, 3a–j, and Cisplatin.

| compound | IC50 (μM) |

SIa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A549 cell line | L929 cell line | ||

| 2 | >500 | >500 | |

| 3a | 91.35 ± 21.89 | >500 | >5.47 |

| 3b | 410.15 ± 220.38 | >500 | |

| 3c | >500 | >500 | |

| 3d | >500 | >500 | |

| 3e | 176.23 ± 56.50 | >500 | >2.84 |

| 3f | 250.61 ± 45.87 | >500 | |

| 3g | 46.60 ± 6.15 | 276.67 ± 28.87 | 5.94 |

| 3h | >500 | >500 | |

| 3i | 83.59 ± 7.30 | >500 | >5.98 |

| 3j | >500 | >500 | |

| Cisplatin | 23.89 ± 2.71 | ||

SI = IC50 for L929 cells/IC50 for A549 cells.

According to the data presented in Table 1, the replacement of the dimethylamino group (compound 3a) with the diethylamino substituent (compound 3b) led to a significant decline in anticancer activity. This outcome indicated that the elongation of the alkyl chains reduced the cytotoxic effect on A549 cells. The bis(2-chloroethyl) and the nitro groups caused the loss of anticancer activity.

Among the six-membered heterocyclic rings (piperidine, morpholine, and piperazine) attached to the 4th position of the benzylidene motif, the piperazine ring gave rise to a significant increase in anticancer activity against A549 cells. On the contrary, the introduction of the pyrrolidine scaffold into the 4th position of the benzylidene group (compound 3h) resulted in the loss of anticancer activity. Taking into account the IC50 values of compounds 3i and 3j (Table 1), the 1H-imidazole core increased the cytotoxic effect on A549 cell line, while the 1H-1,2,4-triazole ring caused the loss of anticancer activity.

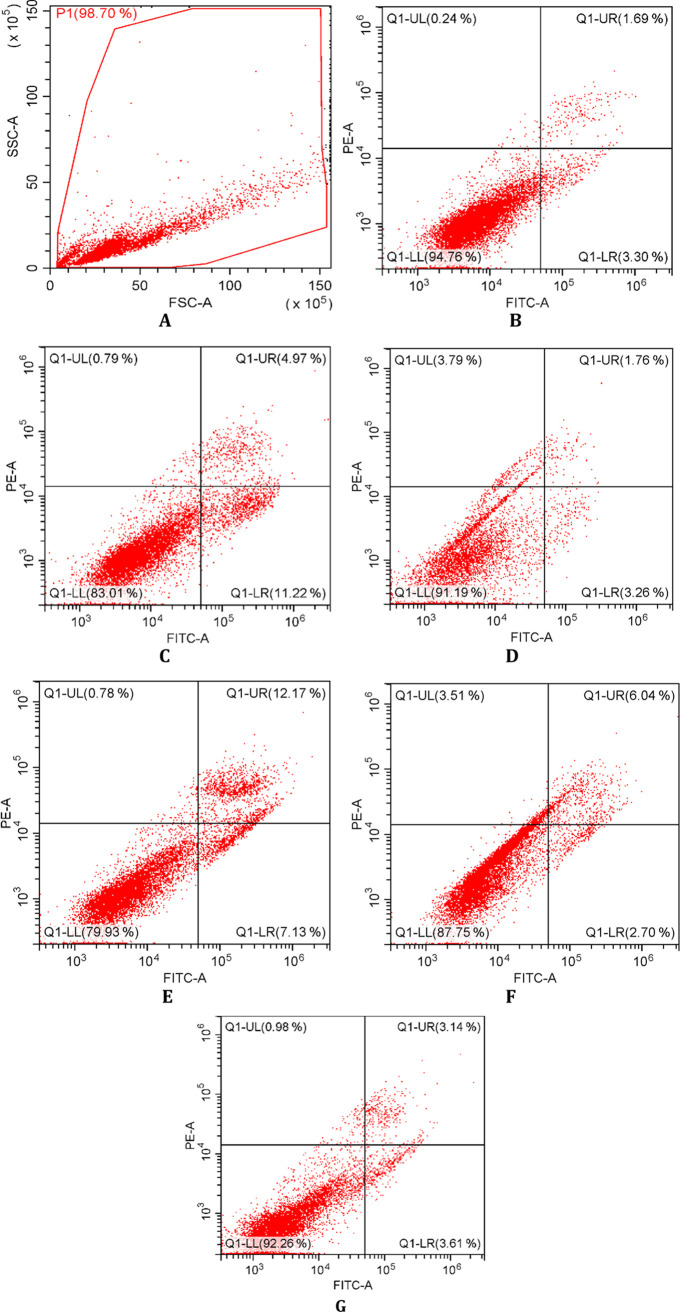

Further studies were carried out for compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3i to illuminate their mechanism of anti-NSCLC action. In this context, after incubation of A549 cells exposed to these agents and cisplatin for 24 h, flow cytometry-based apoptosis detection assay was performed. The percentages of A549 cells undergoing early apoptosis caused by compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, 3i, and cisplatin (at 91.35, 176.23, 46.60, 83.59, and 23.89 μM, respectively) were found to be 11.22, 3.26, 7.13, 2.70, and 3.61%, respectively (Table 2, Figure 2). The percentages of late apoptotic cells induced by compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, 3i, and cisplatin were determined as 4.97, 1.76, 12.17, 6.04, and 3.14%, respectively. In particular, compounds 3a and 3g showed more apoptotic activity than cisplatin in A549 cells.

Table 2. Percents of Typical Quadrant Analysis of Annexin V Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)/PI Flow Cytometry of A549 Cells Exposed to Compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, 3i, and Cisplatin.

| groups | early apoptosis (%) | late apoptosis (%) | necrosis (%) | viability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | 3.30 | 1.69 | 0.24 | 94.76 |

| cells treated with compound 3a | 11.22 | 4.97 | 0.79 | 83.01 |

| cells treated with compound 3e | 3.26 | 1.76 | 3.79 | 91.19 |

| cells treated with compound 3g | 7.13 | 12.17 | 0.78 | 79.93 |

| cells treated with compound 3i | 2.70 | 6.04 | 3.51 | 87.75 |

| cells treated with cisplatin | 3.61 | 3.14 | 0.98 | 92.26 |

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of A549 cells treated with IC50 values of compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, 3i, and cisplatin. At least 10,000 cells were analyzed per sample, and quadrant analysis was performed. Q1-UL, Q1-LL, Q1-UR, and Q1-LR quadrants represent necrosis, viability, and late and early apoptosis, respectively. (A) The main gate selected from the cell population, (B) control, (C) compound 3a, (D) compound 3e, (E) compound 3g, (F) compound 3i, and (G) cisplatin.

A colorimetric method was used to assess the inhibitory effects of compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3i on Akt in A549 cells. Compound 3e carrying a piperidine ring in the 4th position of the benzylidene motif and compound 3i bearing an imidazole ring in the 4th position of the benzylidene moiety inhibited Akt in A549 cells with IC50 values of 105.88 ± 53.71 and 69.45 ± 1.48 μM, respectively, compared to GSK690693 (IC50 = 5.93 ± 1.20 μM), a well-known Akt inhibitor. According to the data indicated in Table 3, it can be concluded that compounds 3e and 3i exert their anti-NSCLC action through the inhibition of Akt.

Table 3. Akt Inhibitory Effects of Compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, 3i, GSK690693, and Cisplatin in A549 Cell Line.

| compound | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| 3a | |

| 3e | 105.88 ± 53.71 |

| 3g | |

| 3i | 69.45 ± 1.48 |

| GSK690693 | 5.93 ± 1.20 |

| Cisplatin | 8.09 ± 0.63 |

Dimethylamino-substituted compound 3a caused 35.40 ± 13.36% Akt inhibition at 91.35 μM. Compound 3g, which carries the 4-methylpiperazine motif in the 4th position of the benzylidene moiety, did not exert any inhibitory effect on Akt. Accordingly, it is obvious that both compounds cause cytotoxicity and apoptosis in A549 cell line via different pathway(s).

2.3. In Silico Studies

Computer-aided drug design tools provide a detailed picture of the biologically active molecules at the molecular level. Our recent successful in silico studies40−42 prompted us to confer molecular docking simulations as a tool to enlighten binding conformations of the ligands.

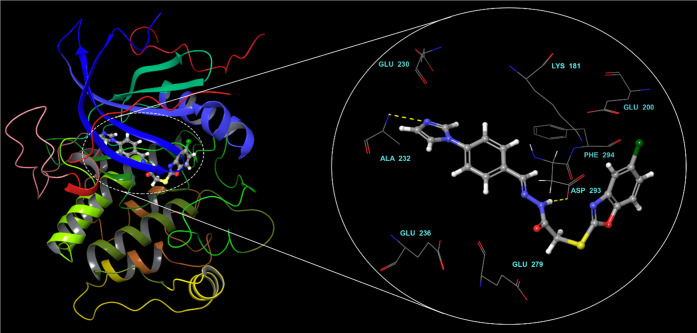

Before moving forward to in silico calculations, internal validation43 was carried out to test how well our docking method performs. The conformation of co-crystallized ligand (GSK690693) was successfully reproduced with Glide XP method yielding a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.436.

Molecular docking studies showed the binding mode of compound 3i within Akt2 binding site (Figure 3). The imidazole nitrogen engages in a key hydrogen bond with the backbone amine of ALA232 in the hinge region. The sulfur linker seems to facilitate compound 3i to adopt a unique binding mode. This folded mode that resembles a V-shaped conformation brings the benzoxazole ring to the vicinity of the acidic pocket. A new hydrogen bond is observed between ASP293 and the N–H of the hydrazide spacer. The interaction of a ligand with this acidic pocket was reported to be important for potent inhibition.44

Figure 3.

Binding mode of compound 3i within the binding region of Akt2.

Certain descriptors related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) were also predicted. Blood–brain barrier parameter was also calculated that could be useful in central nervous system-targeted studies. Of note is that compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3i were estimated to have good pharmacokinetic profiles and druglike properties (Table 4).

Table 4. Predicted ADME Properties of Compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, and 3ia.

| compound | MW | QPlogPo/w | QPlogBBb | HOA%c | PSAd | rule of fivee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | 388.87 | 4.65 | –0.77 | 100.00 | 76.85 | 0.00 |

| 3e | 428.94 | 5.41 | –0.79 | 100.00 | 78.08 | 1.00 |

| 3g | 443.95 | 4.09 | –0.26 | 94.58 | 82.42 | 0.00 |

| 3i | 411.87 | 4.54 | –1.06 | 100.00 | 89.18 | 0.00 |

Octanol/water partition coefficient (recommended range: −2.0 to 6.5).

Brain/blood partition coefficient (recommended range: −3.0 to 1.2).

Human oral absorption (HOA) (<25% is poor, >80% is high).

Polar surface area (PSA) (recommended range: 7.0–200.0).

Number of violations of Lipinski’s rule of five.

3. Conclusions

This paper describes the synthesis of new hydrazones (3a–j) designed as small molecules for NSCLC therapy. Taking into account in vitro cytotoxicity data, selective anticancer agents in this series on A549 cells were determined as compounds 3a (IC50 = 91.35 ± 21.89 μM), 3e (IC50 = 176.23 ± 56.50 μM), 3g (IC50 = 46.60 ± 6.15 μM), and 3i (IC50 = 83.59 ± 7.30 μM). Among them, compounds 3a and 3g caused induction of apoptosis in A549 cells stronger than cisplatin. Both compounds did not exert any significant Akt inhibitory activity in A549 cells, while compounds 3e and 3i caused Akt inhibition in A549 cells. It can be concluded that compounds 3e and 3i exert their cytotoxic action against A549 cell line via the inhibition of Akt. Molecular docking simulations disclosed a unique binding mode for compound 3i (the most active Akt inhibitor in this series) which interacts with the hinge region and the acidic pocket of Akt2. On the other hand, further research is required to shed light on the mechanism of action underlying the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of compounds 3a and 3g on A549 cells.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

The chemicals were procured from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), Maybridge (Loughborough, UK), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Melting points (M.p.) were determined by an Electrothermal IA9200 digital melting point apparatus (Staffordshire, U.K.). IR spectra were acquired from an IRPrestige-21 Fourier Transform (FT)-IR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury-400 FT-NMR spectrometer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA). HRMS spectra were acquired from an LCMS-IT-TOF (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using the electrospray ionization (ESI) technique. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was employed to track the progress of all chemical reactions and examine the purity of the synthesized agents.

4.1.1. Synthesis of Ethyl 2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetate (1)

A mixture of 5-chloro-2-mercaptobenzoxazole (0.06 mol), potassium carbonate (0.06 mol), and ethyl chloroacetate (0.06 mol) in acetone (60 mL) was heated under reflux for 10 h. The precipitated ester was filtered off and washed with distilled water. After drying, the product was crystallized from ethanol.

Yield: 98%, M.p.: 65–67 °C, Lit. M.p.: 64–65 °C.45 IR νmax (cm–1): 3091.89, 3068.75, 3022.45, 2978.09, 2931.80, 1735.93, 1612.49, 1496.76, 1462.04, 1446.61, 1429.25, 1375.25, 1309.67, 1257.59, 1234.44, 1219.01, 1193.94, 1174.65, 1141.86, 1109.07, 1058.92, 1026.13, 937.40, 920.05, 898.83, 867.97, 860.25, 819.75, 767.67, 715.59, 702.09, 677.01. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.19 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 4.16 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.30 (s, 2H), 7.36 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 13.97 (CH3), 33.78 (CH2), 61.57 (CH2), 111.54 (CH), 118.12 (CH), 124.34 (CH), 129.01 (C), 142.37 (C), 150.15 (C), 165.45 (C), 167.69 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C11H10ClNO3S: 272.0143, found, 272.0141.

4.1.2. Synthesis of 2-[(5-Chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (2)

A mixture of compound 1 (0.05 mol) and hydrazine hydrate (0.10 mol) was stirred in ethanol for 5 h at room temperature. The precipitated hydrazide was filtered off and washed with ethanol. After drying, it was crystallized from ethanol.

Yield: 66%, M.p.: 159–161 °C, Lit. M.p.: 190–192 °C.45 IR νmax (cm–1): 3284.77, 3157.47, 3068.75, 2999.31, 2953.02, 2873.94, 1651.07, 1629.85, 1548.84, 1494.83, 1465.90, 1448.54, 1423.47, 1406.11, 1338.60, 1253.73, 1238.30, 1211.30, 1136.07, 1105.21, 1051.20, 1010.70, 956.69, 933.55, 918.12, 864.11, 821.68, 806.25, 773.46, 729.09, 686.66. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 3.35 (brs, 1H), 4.10 (s, 2H), 4.40 (brs, 1H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.86 and 9.44 (2brs, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 34.06 (CH2), 111.50 (CH), 117.99 (CH), 124.24 (CH), 128.93 (C), 142.50 (C), 150.09 (C), 165.45 (C), 165.87 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C9H8ClN3O2S: 258.0099, found, 258.0109.

4.1.3. General Procedure for the Preparation of N′-(4-Subsittuted benzylidene)-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3a–j)

A mixture of compound 2 (0.0012 mol) and 4-substituted benzaldehyde (0.0012 mol) was heated under reflux in ethanol for 8 h. The precipitate was filtered off and washed with ethanol. After drying, the product was crystallized from ethanol.

4.1.3.1. N′-(4-Dimethylaminobenzylidene)-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3a)

Yield: 62%, M.p.: 197–199 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3167.12, 3074.53, 3018.60, 2951.09, 2889.37, 1666.50, 1602.85, 1535.34, 1492.90, 1456.26, 1442.75, 1402.25, 1365.60, 1317.38, 1249.87, 1230.58, 1209.37, 1178.51, 1159.22, 1134.14, 1101.35, 1051.20, 948.98, 937.40, 918.12, 854.47, 819.75, 808.17, 796.60, 786.96, 702.09, 669.30. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.96 (s, 6H), 4.25 and 4.65 (2s, 2H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.91 and 8.06 (2s, 1H), 11.52 and 11.56 (2brs, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 35.02 (CH2), 39.64 (2CH3), 111.42 (CH), 111.73 (2CH), 118.06 (CH), 121.15 (CH), 124.15 (C), 128.24 (2CH), 128.52 (C), 142.58 (C), 144.96 (CH), 150.10 (C), 151.43 (C), 166.32 (C), 167.19 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C18H17ClN4O2S: 389.0834, found, 389.0853.

4.1.3.2. N′-(4-Diethylaminobenzylidene)-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3b)

Yield: 65%, M.p.: 172–173 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3172.90, 3082.25, 2968.45, 2927.94, 2893.22, 1666.50, 1610.56, 1597.06, 1527.62, 1494.83, 1463.97, 1444.68, 1421.54, 1400.32, 1386.82, 1375.25, 1350.17, 1313.52, 1273.02, 1253.73, 1213.23, 1197.79, 1182.36, 1155.36, 1134.14, 1105.21, 1082.07, 1051.20, 1012.63, 1004.91, 954.76, 929.69, 914.26, 881.47, 860.25, 813.96, 779.24, 758.02, 715.59, 700.16, 677.01. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.09 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H), 3.34–3.39 (m, 4H), 4.25 and 4.64 (2s, 2H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (dd, J = 10.0 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.88 and 8.03 (2s, 1H), 11.49 and 11.52 (2s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 12.41 (2CH3), 35.01 (CH2), 43.74 (2CH2), 111.02 (2CH), 111.47 (CH), 118.06 (CH), 120.22 (CH), 124.15 (C), 128.57 (2CH), 128.91 (C), 142.59 (C), 145.00 (CH), 148.77 (C), 150.11 (C), 166.33 (C), 167.14 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H21ClN4O2S: 417.1147, found, 417.1171.

4.1.3.3. N′-[4-(Bis(2-chloroethyl)amino)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3c)

Yield: 47%, M.p.: 155–156 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3180.62, 3072.60, 3012.81, 2962.66, 2895.15, 1662.64, 1598.99, 1525.69, 1510.26, 1494.83, 1448.54, 1413.82, 1390.68, 1355.96, 1315.45, 1276.88, 1255.66, 1203.58, 1176.58, 1136.07, 1107.14, 1053.13, 958.62, 929.69, 916.19, 910.40, 864.11, 815.89, 804.32, 746.45, 717.52, 678.94. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 3.74–3.79 (m, 8H), 4.26 and 4.65 (2s, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 9.0 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.91 and 8.07 (2s, 1H), 11.56 and 11.60 (2s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 35.00 (CH2), 40.98 (2CH2), 51.85 (2CH2), 111.46 (CH), 111.76 (2CH), 118.06 (CH), 122.29 (CH), 124.15 (C), 128.59 (2CH), 128.91 (C), 142.56 (C), 144.53 (CH), 147.94 (C), 150.11 (C), 166.28 (C), 167.31 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H19Cl3N4O2S: 485.0367, found, 485.0394.

4.1.3.4. N′-(4-Nitrobenzylidene)-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3d)

Yield: 88%, M.p.: 237–239 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3201.83, 3093.82, 2960.73, 2846.93, 1680.00, 1614.42, 1597.06, 1585.49, 1516.05, 1487.12, 1452.40, 1404.18, 1379.10, 1336.67, 1255.66, 1226.73, 1201.65, 1151.50, 1139.93, 1112.93, 1105.21, 1064.71, 929.69, 918.12, 898.83, 889.18, 860.25, 850.61, 833.25, 821.68, 804.32, 748.38, 736.81, 704.02, 690.52. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 4.33 and 4.73 (2s, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73–7.74 (m, 1H), 7.96–7.99 (m, 2H), 8.14 (s, 1H), 8.26–8.32 (m, 2H), 12.09 (brs, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 34.76 (CH2), 111.48 (CH), 118.06 (CH), 124.02 (2CH), 124.21 (CH), 127.89 (2CH), 128.94 (C), 140.14 (C), 142.49 (C), 144.87 (CH), 147.80 (C), 150.11 (C), 166.02 (C), 168.27 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C16H11ClN4O4S: 391.0262, found, 391.0278.

4.1.3.5. N′-[4-(Piperidin-1-yl)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3e)

Yield: 77%, M.p.: 187–188 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3165.19, 3076.46, 3008.95, 2920.23, 2850.79, 1664.57, 1600.92, 1523.76, 1494.83, 1456.26, 1442.75, 1425.40, 1386.82, 1354.03, 1315.45, 1226.73, 1209.37, 1184.29, 1163.08, 1126.43, 1099.43, 1051.20, 1020.34, 952.84, 935.48, 918.12, 852.54, 806.25, 794.67, 715.59, 702.09, 677.01. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.56 (brs, 6H), 3.24 (brs, 4H), 4.26 and 4.65 (2s, 2H), 6.91–6.95 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.8 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 7.8 Hz, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.91 and 8.06 (2s, 1H), 11.56 and 11.61 (2s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 23.92 (CH2), 24.95 (2CH2), 34.98 (CH2), 48.40 (2CH2), 111.47 (CH), 114.58 (2CH), 118.06 (CH), 122.94 (CH), 124.15 (C), 128.18 (2CH), 128.47 (C), 142.57 (C), 144.62 (CH), 150.11 (C), 152.35 (C), 166.28 (C), 167.30 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H21ClN4O2S: 429.1147, found, 429.1153.

4.1.3.6. N′-[4-(Morpholin-4-yl)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3f)

Yield: 82%, M.p.: 209–210 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3180.62, 3078.39, 3010.88, 2962.66, 2854.65, 1666.50, 1604.77, 1523.76, 1498.69, 1446.61, 1425.40, 1400.32, 1381.03, 1311.59, 1269.16, 1253.73, 1228.66, 1211.30, 1184.29, 1166.93, 1132.21, 1122.57, 1111.00, 1101.35, 1051.20, 948.98, 927.76, 918.12, 862.18, 819.75, 808.17, 792.74, 717.52, 702.09, 677.01. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 3.19 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.28 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.71–3.75 (m, 4H), 4.26 and 4.66 (2s, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.94 and 8.10 (2s, 1H), 11.63 (brs, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 34.91 (CH2), 46.90 (2CH2), 65.82 (2CH2), 111.44 (CH), 113.78 (2CH), 117.51 (CH), 122.25 (CH), 124.55 (C), 128.09 (C), 130.12 (2CH), 142.55 (C), 144.46 (CH), 150.09 (C), 152.16 (C), 166.24 (C), 167.37 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H19ClN4O3S: 431.0939, found, 431.0954.

4.1.3.7. N′-[4-(4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3g)

Yield: 35%, M.p.: 178–179 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3205.69, 3061.03, 2949.16, 2935.66, 2845.00, 2802.57, 1654.92, 1610.56, 1600.92, 1562.34, 1517.98, 1496.76, 1448.54, 1425.40, 1409.96, 1381.03, 1361.74, 1315.45, 1294.24, 1251.80, 1234.44, 1209.37, 1190.08, 1161.15, 1130.29, 1107.14, 1078.21, 1055.06, 999.13, 960.55, 918.12, 875.68, 819.75, 794.67, 700.16, 673.16. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.23 (s, 3H), 2.45 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 3.24 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H), 4.28 and 4.67 (2s, 2H), 6.96–6.99 (m, 2H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, 4.4 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (dd, J = 7.4 Hz, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.94 and 8.10 (2s, 1H), 11.60 and 11.66 (2s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 34.97 (CH2), 45.74 (CH3), 47.09 (2CH2), 54.40 (2CH2), 111.47 (CH), 114.50 (2CH), 118.07 (CH), 123.63 (CH), 124.17 (C), 128.16 (2CH), 128.40 (C), 128.91 (C), 142.57 (C), 144.53 (CH), 150.11 (C), 166.28 (C), 167.35 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H22ClN5O2S: 444.1255, found, 444.1278.

4.1.3.8. N′-[4-(Pyrrolidin-1-yl)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3h)

Yield: 82%, M.p.: 206–207 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3170.97, 3080.32, 2976.16, 2956.87, 2096.73, 2850.79, 1666.50, 1612.49, 1598.99, 1529.55, 1494.83, 1448.54, 1436.97, 1386.82, 1348.24, 1315.45, 1301.95, 1249.87, 1217.08, 1178.51, 1163.08, 1138.00, 1107.14, 1049.28, 958.62, 931.62, 916.19, 902.69, 858.32, 810.10, 779.24, 700.16, 675.09. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 1.93–1.98 (m, 4H), 3.26 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 4.25 and 4.64 (2s, 2H), 6.52–6.56 (m, 2H), 7.35 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (dd, J = 9.0 Hz, 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.66–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.89 and 8.05 (2s, 1H), 11.47 and 11.51 (2s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 24.93 (2CH2), 34.99 (CH2), 47.19 (2CH2), 111.42 (CH), 111.49 (2CH), 118.03 (CH), 122.25 (CH), 124.12 (C), 128.36 (2CH), 128.64 (C), 142.57 (C), 145.19 (CH), 148.82 (C), 150.08 (C), 166.30 (C), 167.08 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H19ClN4O2S: 415.0990, found, 415.1013.

4.1.3.9. N′-[4-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3i)

Yield: 83%, M.p.: 229–231 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3159.40, 3099.61, 2978.09, 2823.79, 1705.07, 1608.63, 1577.77, 1521.84, 1487.12, 1465.90, 1448.54, 1427.32, 1400.32, 1359.82, 1305.81, 1263.37, 1228.66, 1215.15, 1176.58, 1136.07, 1107.14, 1060.85, 989.48, 962.48, 927.76, 916.19, 866.04, 835.18, 817.82, 719.45, 702.09, 680.87, 651.94. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 4.31 and 4.71 (2s, 2H), 7.14 (brs, 1H), 7.34 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.73–7.76 (m, 3H), 7.82–7.86 (m, 3H), 8.08 and 8.26 (2s, 1H), 8.35 (brs, 1H), 11.86 and 11.92 (2s, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 34.81 (CH2), 111.44 (CH), 117.78 (CH), 118.03 (CH), 120.29 (2CH), 124.17 (CH), 128.38 (2CH), 128.90 (CH), 130.13 (C), 132.28 (C), 135.54 (CH), 137.80 (C), 142.51 (C), 143.05 (CH), 150.09 (C), 166.11 (C), 167.89 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C19H14ClN5O2S: 412.0629, found, 412.0659.

4.1.3.10. N′-[4-(1H-1,2,4-Triazol-1-yl)benzylidene]-2-[(5-chlorobenzoxazol-2-yl)thio]acetohydrazide (3j)

Yield: 80%, M.p.: 256–257 °C. IR νmax (cm–1): 3207.62, 3124.68, 3088.03, 2951.09, 2829.57, 1670.35, 1614.42, 1523.76, 1492.90, 1452.40, 1402.25, 1373.32, 1344.38, 1319.31, 1280.73, 1246.02, 1219.01, 1201.65, 1143.79, 1107.14, 1051.20, 979.84, 960.55, 916.19, 889.18, 833.25, 819.75, 790.81, 702.09, 671.23. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 4.29 and 4.72 (2s, 2H), 7.34 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 8.6 Hz, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.72–7.74 (m, 1H), 7.87–7.96 (m, 4H), 8.09 and 8.26 (2s, 1H), 8.27 (s, 1H), 9.37 (s, 1H), 11.87 (brs, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 34.83 (CH2), 111.43 (CH), 118.03 (CH), 119.49 (2CH), 124.16 (CH), 128.30 (2CH), 128.51 (C), 133.19 (C), 137.51 (C), 142.45 (CH), 142.51 (C), 142.95 (CH), 150.09 (C), 152.57 (CH), 166.10 (C), 167.91 (C). HRMS (ESI) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C18H13ClN6O2S: 413.0582, found, 413.0607.

4.2. Biochemistry

4.2.1. Cell Culture and Drug Treatment

A549 and L929 cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured, and drug treatments were performed as previously explained.46

4.2.2. MTT Test

MTT assay was conducted as previously described47 with slight modifications.48 Cisplatin was used as a positive control. The assay was performed in triplicate. Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) data (μM) were expressed as mean ± SD.

4.2.3. Flow Cytometric Analyses of Apoptosis

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) was applied using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions following the 24 h incubation of A549 cells with compounds 3a, 3e, 3g, 3i, and cisplatin at 91.35, 176.23, 46.60, 83.59, and 23.89 μM, respectively.

4.2.4. Determination of Akt Inhibition

Akt Colorimetric In-Cell ELISA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer after A549 cells were incubated with compounds 3a (22.84, 45.68, and 91.35 μM), 3e (44.06, 88.12, and 176.23 μM), 3g (11.65, 23.30, and 46.60 μM), 3i (20.90, 41.80, and 83.59 μM), cisplatin (5.97, 11.95, and 23.89 μM), and GSK690693 (3.61, 7.23, and 14.45 μM) for 24 h. The assay was performed in triplicate. IC50 data (μM) were expressed as mean ± SD.

4.2.5. Statistical Analyses

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows 15.0 was used for statistical analysis. Comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA test for normally distributed continuous variables, and post hoc analyses of group differences were expressed by the Tukey test.

4.3. In Silico Studies

The crystal structure of human Akt2 in complex with GSK690693 was downloaded from Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3D0E at 2.00 Å resolution). This raw protein structure was initially prepared49 by adding missing hydrogens, correcting bond orders, and removing all heteroatoms except the native ligand. The structure was then optimized to address any overlapping hydrogens, and finally, restrained minimization was carried out.

The binding site of Akt2 was defined by computing grid file using GSK690693 as a reference agent. The size of enclosing box that represents grid was extended to allow docking of the ligands with length <20 Å. Glide XP module50 was selected for molecular docking. LigPrep module51 was used to prepare ligands for in silico calculations to consider all possible geometries, tautomers, and also protonation states at physiological conditions. Important molecular descriptors related to ADME were predicted using QikProp module.52

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c02331.

IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS spectra of compounds 1, 2, and 3a–j (PDF)

Author Contributions

M.D.A. and A.Ö. designed the research; B.E. and M.D.A. performed the synthesis and characterization of all compounds; A.E. carried out molecular docking and in silico ADME studies; G.A.Ç. performed in vitro experimental studies. M.D.A. mainly wrote manuscript. M.D.A. was responsible for the correspondence of the manuscript. All authors discussed, edited, and approved the final version.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arya S. K.; Bhansali S. Lung cancer and its early detection using biomarker based biosensors. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6783–6809. 10.1021/cr100420s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H.; Ferlay J.; Siegel R. L.; Laversanne M.; Soerjomataram I.; Jemal A.; Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T.; Bao X.; Chen M.; Lin R.; Zhuyan J.; Zhen T.; Xing K.; Zhou W.; Zhu S. Mechanisms and future of non-small cell lung cancer metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 585284 10.3389/fonc.2020.585284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janku F.; Stewart D. J.; Kurzrock R. Targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer-is it becoming a reality?. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 401–414. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayan A. P.; Anandu K. R.; Madhu K.; Saiprabha V. N. A pharmacological exploration of targeted drug therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 147. 10.1007/s12032-022-01744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento A. V.; Bousbaa H.; Ferreira D.; Sarmento B. Non-small cell lung carcinoma: An overview on targeted therapy. Curr. Drug Targets 2015, 16, 1448–1463. 10.2174/1389450115666140528151649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Zhu T.; Gao Y.-F.; Zheng W.; Wang C.-J.; Xiao L.; Huang M.-S.; Yin J.-Y.; Zhou H.-H.; Liu Z.-Q. Targeting DNA damage response in the radio(chemo)therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 839. 10.3390/ijms17060839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iksen; Pothongsrisit S.; Pongrakhananon V. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in lung cancer: An update regarding potential drugs and natural products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4100. 10.3390/molecules26134100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa Iglesias V.; Giuranno L.; Dubois L. J.; Theys J.; Vooijs M. Drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer: A potential for NOTCH targeting?. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 267. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.; Shang Z.; Dai A.-l.; Dai P.-l. Novel PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors plus radiotherapy: Strategy for non-small cell lung cancer with mutant RAS gene. Life Sci. 2020, 255, 117816 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; Chen L.; Wu J.; Ai D.; Zhang J. Q.; Chen T. G.; Wang L. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in the treatment of human diseases: Current status, trends, and solutions. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 16033–16061. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M.; Bode A. M.; Dong Z.; Lee M. H. AKT as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 1019–1031. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitulescu G. M.; Margina D.; Juzenas P.; Peng Q.; Olaru O. T.; Saloustros E.; Fenga C.; Spandidos D. A.; Libra M.; Tsatsakis A. M. Akt inhibitors in cancer treatment: The long journey from drug discovery to clinical use (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 869–885. 10.3892/ijo.2015.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali S. N.; Thorat B. R.; Gupta D. R.; Pandey A. Mini-review of the importance of hydrazides and their derivatives-Synthesis and biological activity. Eng. Proc. 2021, 11, 21. 10.3390/ASEC2021-11157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popiołek Ł. Hydrazide-hydrazones as potential antimicrobial agents: Overview of the literature since 2010. Med. Chem. Res. 2017, 26, 287–301. 10.1007/s00044-016-1756-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew B.; Suresh J.; Ahsan M. J.; Mathew G. E.; Usman D.; Subramanyan P. N. S.; Safna K. F.; Maddela S. Hydrazones as a privileged structural linker in antitubercular agents: A review. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 15, 76–88. 10.2174/1871526515666150724104411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahbeh J.; Milkowski S. The use of hydrazones for biomedical applications. SLAS Technol. 2019, 24, 161–168. 10.1177/2472630318822713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollas S.; Küçükgüzel S. G. Biological activities of hydrazone derivatives. Molecules 2007, 12, 1910–1939. 10.3390/12081910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altıntop M. D.; Akalın Çiftçi G.; Yılmaz Savaş N.; Ertorun İ.; Can B.; Sever B.; Temel H. E.; Alataş Ö.; Özdemir A. Discovery of small molecule COX-1 and Akt inhibitors as anti-NSCLC agents endowed with anti-inflammatory action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2648. 10.3390/ijms24032648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şenkardeş S.; Han M.İ.; Gürboğa M.; Bingöl Özakpinar Ö.; Küçükgüzel Ş.G. Synthesis and anticancer activity of novel hydrazone linkage-based aryl sulfonate derivatives as apoptosis inducers. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 368–379. 10.1007/s00044-021-02837-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Güngör E. M.; Altıntop M. D.; Sever B.; Akalın Çiftçi G. Design, synthesis, in vitro and in silico evaluation of new hydrazone-based antitumor agents as potent Akt inhibitors. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery 2020, 17, 1380–1392. 10.2174/1570180817999200618163507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.İ.; Bekçi H.; Uba A. I.; Yıldırım Y.; Karasulu E.; Cumaoğlu A.; Karasulu H. Y.; Yelekçi K.; Yılmaz Ö.; Küçükgüzel Ş.G. Synthesis, molecular modeling, in vivo study, and anticancer activity of 1,2,4-triazole containing hydrazide–hydrazones derived from (S)-naproxen. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 2019, 352, e1800365 10.1002/ardp.201800365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan A.; Kute D.; Musa A.; Konda Mani S.; Sipilä V.; Emmert-Streib F.; Zubkov F. I.; Gurbanov A. V.; Yli-Harja O.; Kandhavelu M. 2-(2-(2,4-Dioxopentan-3-ylidene)hydrazineyl)benzonitrile as novel inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in glioblastoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 166, 291–303. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Li H.; Luo H.; Lin Z.; Luo W. Synthesis and evaluation of pyridoxal hydrazone and acylhydrazone compounds as potential angiogenesis inhibitors. Pharmacology 2019, 104, 244–257. 10.1159/000501630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M. S.; Lee D. U. Synthesis, biological evaluation, drug-likeness, and in silico screening of novel benzylidene-hydrazone analogues as small molecule anticancer agents. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2016, 39, 191–201. 10.1007/s12272-015-0699-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak Y.; Kim H.; Kang J. W.; Lee D. H.; Kim M. S.; Park Y. S.; Kim J. H.; Jung K. Y.; Lim Y.; Hong J.; Yoon D. Y. A synthetic naringenin derivative, 5-hydroxy-7,4′-diacetyloxyflavanone-N-phenyl hydrazone (N101-43), induces apoptosis through up-regulation of Fas/FasL expression and inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling pathways in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 10286–10297. 10.1021/jf2017594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong X. K.; Yeong K. Y. A patent review on the current developments of benzoxazoles in drug discovery. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 3237–3262. 10.1002/cmdc.202100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale M.; Chavan V. Exploration of the biological potential of benzoxazoles: An overview. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2019, 16, 111–126. 10.2174/1570193X15666180627125007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.-Z.; Zhao Z.-L.; Zhou C.-H. Recent advance in oxazole-based medicinal chemistry. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 144, 444–492. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar S.; Maiti B.; Chanda K. A decade update on benzoxazoles, a privileged scaffold in synthetic organic chemistry. Synlett 2017, 28, 521–541. 10.1055/s-0036-1588671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demmer C. S.; Bunch L. Benzoxazoles and oxazolopyridines in medicinal chemistry studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 778–785. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghour M. S.; Mahdy H. A.; Gomaa M. H.; Aglan A.; Eldeib M. G.; Elwan A.; Dahab M. A.; Elkaeed E. B.; Alsfouk A. A.; Khalifa M. M.; Eissa I. H.; Elkady H. Benzoxazole derivatives as new VEGFR-2 inhibitors and apoptosis inducers: Design, synthesis, in silico studies, and antiproliferative evaluation. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 2063–2077. 10.1080/14756366.2022.2103552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar A.-M. M. E.; AboulWafa O. M.; El-Shoukrofy M. S.; Amr M. E. Benzoxazole derivatives as new generation of anti-breast cancer agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 96, 103593 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glamočlija U.; Padhye S.; Špirtović-Halilović S.; Osmanović A.; Veljović E.; Roca S.; Novaković I.; Mandić B.; Turel I.; Kljun J.; Trifunović S.; Kahrović E.; Kraljević Pavelić S.; Harej A.; Klobučar M.; Završnik D. Synthesis, biological evaluation and docking studies of benzoxazoles derived from thymoquinone. Molecules 2018, 23, 3297 10.3390/molecules23123297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghmaei S.; Ghalayania P.; Salami S.; Nourmohammadian F.; Koohestanimobarhan S.; Imeni V. Hybrid benzoxazole-coumarin compounds induce death receptor-mediated switchable apoptotic and necroptotic cell death on HN-5 head and neck cancer cell line. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 608–614. 10.2174/1871520616666160725110844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelgawad M. A.; Bakr R. B.; Omar H. A. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of some novel benzothiazole/benzoxazole and/or benzimidazole derivatives incorporating a pyrazole scaffold as antiproliferative agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 74, 82–90. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belal A.; Abdelgawad M. A. New benzothiazole/benzoxazole-pyrazole hybrids with potential as COX inhibitors: design, synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 3859–3872. 10.1007/s11164-016-2851-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An Y.; Lee E.; Yu Y.; Yun J.; Lee M. Y.; Kang J. S.; Kim W.-Y.; Jeon R. Design and synthesis of novel benzoxazole analogs as Aurora B kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 3067–3072. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskin T.; Yilmaz S.; Yildiz I.; Yalcin I.; Aki E. Insight into eukaryotic topoisomerase II-inhibiting fused heterocyclic compounds in human cancer cell lines by molecular docking. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2012, 23, 345–355. 10.1080/1062936X.2012.664560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulut Z.; Abul N.; Poslu A. H.; Gülçin İ.; Ece A.; Erçağ E.; Koz Ö.; Koz G. Structural characterization and biological evaluation of uracil-appended benzylic amines as acetylcholinesterase and carbonic anhydrase I and II inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1280, 135047 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efeoglu C.; Yetkin D.; Nural Y.; Ece A.; Seferoğlu Z.; Ayaz F. Novel urea-thiourea hybrids bearing 1, 4-naphthoquinone moiety: Anti-inflammatory activity on mammalian macrophages by regulating intracellular PI3K pathway, and molecular docking study. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1264, 133284 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.; Frankish N.; Zhang T.; Ece A.; Cannon A.; O’Sullivan J.; Sheridan H. Bioactive indanes: insight into the bioactivity of indane dimers related to the lead anti-inflammatory molecule PH46A. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020, 72, 927–937. 10.1111/jphp.13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ece A. Computer-aided drug design. BMC Chem. 2023, 17, 26 10.1186/s13065-023-00939-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies T. G.; Verdonk M. L.; Graham B.; Saalau-Bethell S.; Hamlett C. C. F.; McHardy T.; Collins I.; Garrett M. D.; Workman P.; Woodhead S. J.; Jhoti H.; Barford D. A structural comparison of inhibitor binding to PKB, PKA and PKA-PKB chimera. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 367, 882–894. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M.-K.; El-Adl K.; Zayed M. F.; Mahdy H. A. Design, synthesis, docking, and biological evaluation of some novel 5-chloro-2-substituted sulfanylbenzoxazole derivatives as anticonvulsant agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 99–114. 10.1007/s00044-014-1111-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altıntop M. D.; Sever B.; Akalın Çiftçi G.; Özdemir A. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of a new series of thiazole-based anticancer agents as potent Akt inhibitors. Molecules 2018, 23, 1318. 10.3390/molecules23061318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orujova T.; Ece A.; Akalın Çiftçi G.; Özdemir A.; Altıntop M. D. A new series of thiazole-hydrazone hybrids for Akt-targeted therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Dev. Res. 2023, 84, 185–199. 10.1002/ddr.22022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protein Preparation Wizard, version 2023-1; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2023.

- Friesner R. A.; Murphy R. B.; Repasky M. P.; Frye L. L.; Greenwood J. R.; Halgren T. A.; Sanschagrin P. C.; Mainz D. T. Extra precision glide: Docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein– ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6177–6196. 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LigPrep, version 2023-1; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2023.

- QikProp, version 2023-1; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.