Abstract

This study assessed the influence of occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience on the safety performance of healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Demographic variables including age, work experience, and gender were explored. Data were collected from 344 healthcare providers employed at a teaching hospital. The entropy method and the multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method were used to examine the influence of occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience on the safe performance of healthcare providers. The results of the entropy method showed that organizational resilience was the most influential factor in the safe performance of older healthcare providers. In contrast, individual resilience was the most significant factor in enhancing the safety performance of younger healthcare providers. Analyses of work experience indicated that individual resilience was the most influential factor in the safe performance of less experienced healthcare providers. Gender-based analysis revealed that individual resilience had a major effect on the safety performance of both women and men. The findings of this study could assist managers in improving the performance of the healthcare sector during pandemics by using and implementing resilience concepts at both the individual and organizational levels.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Safe performance, Individual resilience, Organizational resilience, Demographic variables, Entropy method

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease that has spread rapidly. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus pandemic a global pandemic on 11th March 2020 [1,2]. Many cases of COVID-19 have been reported worldwide [3]. The resulting high patient volume has led to mental and physical health issues for healthcare workers [4,5].

Healthcare providers providing frontline COVID-19 care are at a high risk of contracting COVID-19. Additionally, because of the high patient volumes and direct care of COVID-19 patients, healthcare providers suffer from other problems such as physical and emotional stress [6,7], working under intense stress levels [8], high workloads, work-related burnout [9], and risk of moral injury and mental health issues [10].

Work-related stress can affect an individual's well-being and psychological and behavioral variables, task performance, cognitive functioning, and safety. Working under stress can lead to increase error rates in duties [11], [12], [13]. Work-related stress has negative effects on an individual's mental health [14,15]. Occupational stress may also influence quality of social and family life [16]. Some organizational determinants of work-related stress include job characteristics, role-related factors, organizational structure, climate, information flow, relationships at work, and responsibilities [17]. Previous research proposed that resilience can help maintain healthy psychological profiles. Resilient employees experience less work-related stress and burnout [18,19].

Resilience is a multidimensional and multidisciplinary concept. The literature describes two different perspectives on resilience: individual and organizational resilience [20,21]. Individual resilience is the capacity of individuals to adapt successfully to significant changes, adversity, or risk [20]. Individual resilience can help individuals deal with stressors, such as pressure in the work environment. Individual resilience positively impacts employee performance by reducing counterproductive behaviors and improving stress management. Individual resilience was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, better safety performance, lower levels of work-related stress, better coping abilities, lower intentions to quit, and higher levels of change acceptance [20]. In addition, previous work has mentioned significant relationships between organizational commitment, work happiness, job satisfaction, and individual resilience [20]. Resilience, as a positive psychological capacity, improves stress-coping abilities [22,23]. Resilience is essential for understanding individual stress [24]. Individual and organizational resilience develop capacities and positive functioning to cope successfully in the face of adversity and overcome potentially debilitating consequences [25].

Organizational resilience, an important factor in organizational success, is defined as an organization's ability to anticipate potential threats, cope with adverse events more effectively, and adapt to changing conditions and sudden disruptions [26], [27], [28]. Improvements in resilience at both the individual and organizational levels are associated with higher stress-coping abilities and can help organizations and individuals thrive and survive in the face of unexpected disruptions [29].

Resilience frameworks can be applied to improve health and safety in workplaces during the COVID-19 pandemic [30]. According to the literature, some dimensions of organizational resilience, such as management commitment, preparedness, awareness, reporting culture, and learning, play key roles in worker safety performance [28]. Furthermore, several studies found evidence supporting the positive role of resilience frameworks in enhancing and maintaining the safety of complex systems [31,32]. Resilience is regarded as a proactive approach to identifying what is right. In a resilient system, the ability to successfully cope with undesirable outcomes is based on a set of resources, capacities, and suitable organizational structures [21,33]. Organizational and individual resilience factors provide appropriate measures for coping with adverse events in high-risk environments. Individuals cope with unexpected events by adjusting their behavior according to the conditions [34,35]. Therefore, as a growing concept, resilience can improve the performance of critical industrial units [36]. In a high-risk workplace, the resilience approach can help improve safety behaviors and the safety of a system [37].

Safety performance was based on job performance theories. It is associated with task-based behaviors in a given job and efforts to improve workplace [38]. Safety behavior (performance) is an employee involvement activity that must be conducted by workers to maintain personal and workplace safety and involves activities conducted by workers to develop an environment that supports safety [38]. Behavioral testing of employees is a common measure of safety performance in workplace settings [12,28,39]. Resilience-related factors are considered as means to improve safety performance and adapt successfully to undesirable events and disturbances [20,40].

Previous research has demonstrated that demographic variables, such as age, work experience, and gender, can significantly affect safety performance [41], safety-related behaviors [42], and resilience outcomes [43]. Significant differences between safety citizenship behaviors were found for different genders, and safety-related behaviors of female workers were significantly lower than those of male workers in a study conducted among construction workers [42]. Additionally, in a study conducted among gas refinery employees, older and more experienced workers showed better safety performance than younger workers [41].

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected healthcare providers. Healthcare workers experience high stress levels, psychological distress, heavy workloads, intense work pressure [44], and a high prevalence of burnout [9]. Healthcare providers’ ability to maintain good functioning in the face of COVID-19 and stress exposure is also important for an effective response to stressful working environments [24], [43]. The resilience of healthcare systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic is another critical factor [45]. Health-system resilience refers to the capacity of healthcare institutions to prepare for and effectively respond to crises and to maintain core functions during the pandemic [45], [46]. The four abilities of a resilient system are monitoring, anticipation, response, and learning [47].

Previous studies used appropriate techniques, such as multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approaches, to compute the weights (importance) of factors influencing safety in high-risk sectors [48]. The entropy method, which is an MCDM approach, is a common weighting approach used to obtain the weights of different criteria [49]. It is based on Shannon entropy theory [50]. Owing to the different importance of each criterion (factor), weights should be assigned to the criteria as an important outcome of MCDM approaches. The entropy approach is a helpful technique to solve weighting-related problems in different fields [51,52].

Although many studies have considered the importance of demographic and job-related factors in the safety performance of workers [41,53,54], few have focused on the role of demographic factors in workers’ safety performance regarding individual and organizational resilience and occupational stress in combination using MCDM approaches. To address this gap, this study aimed to examine the role of occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience in healthcare providers’ safety performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. The entropy method was employed to explore factors influencing healthcare providers’ safety performance by examining demographic variables.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

The study was conducted in a teaching hospital (a referral center for COVID‐19) in Iran in 2021–2022. A questionnaire was used to assess the study factors and variables. Healthcare providers (who interacted with COVID-19 patients) in different job positions, such as medical doctors, nurses, radiologists, medical laboratory staff, and surgical and anesthesia staff, were requested to complete the questionnaires.

The current study included male and female healthcare providers at the study hospital. The desired sample size considering alpha error (α) of 0.05, Z = 1.96 for a 95% significance level, and a drop-out rate of 10% was 374 participants. Among healthcare providers, three hundred and forty-four were enrolled in the study (participation rate of 92%). Although a larger sample size in qualitative research is necessary to increase the validity of the research, the results can be used as input for further research and can also provide a deep understanding of the research questions [55,56]. Table 1 shows the demographic information (individual variables) including age, gender, and work experience of respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic information of respondents.

| Demographic variable |

N = 344 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| 1. Male | 110 | 32 |

| 2. Female |

234 | 68 |

| Age | ||

| 1. 20–30 | 118 | 34 |

| 2. 31–40 | 152 | 44 |

| 3. 41–50 | 64 | 19 |

| 4. Older than 50 |

10 | 3 |

| Work experience | ||

| 1. Less than 5 years | 104 | 30 |

| 2. 5–10 years | 96 | 28 |

| 3. 10–15 years | 113 | 33 |

| 4. 15–20 years | 21 | 6 |

| 5. More than 20 years | 10 | 3 |

2.2. Measures

Five-point scales were used to rate items (1= strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree). The individual score for each measure was determined by averaging the scores of the items. A higher score indicates a higher level for each measure. For all measures, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to determine reliability. In this study, the safety performance of healthcare providers was measured using items related to occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience [57]. A Cronbach's alpha value of 0.70 and above was generally considered acceptable for internal consistency [58,59].

2.2.1. Occupational stress

The effect of occupational stress on health care providers’ safety performance was assessed using six items adapted from Parker and DeCotiis [17]. An example item includes: “I have felt fidgety or nervous as a result of my job.” Higher scores for each item represent a greater level of occupational stress. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire, which has good psychometric properties, were tested in a study conducted in Iran by Damiri et al. [60] that has good psychometric properties. The Cronbach's alpha for the sample in the current study was 0.76.

2.2.2. Individual resilience

The effect of individual resilience on healthcare providers’ safety performance was measured using eight items adapted from Campbell-Sills and Stein [24]. An example item includes: “I am able to adapt to change.” Higher scores on these items represent higher levels of individual resilience and safe performance. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the questionnaire were investigated in a previous study with older adults (content validity ratio = 0.85, content validity index =0.90) [61]. The Cronbach's alpha for the sample in the current study was 0.78.

2.2.3. Organizational resilience

The effect of organizational resilience factors on healthcare providers’ safety performance was assessed using 16 items prepared by Hollnagel [47]. This measure contains four factors or dimensions that consider the four abilities of resilient systems: response, monitoring, anticipation, and learning. Responding refers to the ability to respond to an event. Monitoring represents the ability to monitor ongoing developments. Anticipation refers to the ability to anticipate future threats, and learning refers to the ability to learn from past adverse events and successes [47]. An example item for monitoring is: “In the hospital, assessments of factors influencing employees’ safe performance (safe behaviors) are performed frequently.” Higher scores on these items represent a higher level of organizational resilience and safe performance. Omidi et al. [28] reported good internal consistency for this questionnaire (Cronbach's alpha = 0.79). The Cronbach's alpha for the sample was 0.91.

The raw data (mean and standard deviation) of this study are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Raw data.

| Factor | Occupational stress | Individual resilience | Organizational resilience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| 1. Male | 3.38±0.82 | 3.78±0.65 | 3.54±0.61 |

| 2. Female | 3.48±0.78 | 3.66±068 | 3.34±0.64 |

| Age | |||

| 1. 20–30 | 3.45±0.78 | 3.70±0.67 | 3.33±0.59 |

| 2. 31–40 | 3.49±0.80 | 3.69±0.70 | 3.39±0.68 |

| 3. 41–50 | 3.46±0.86 | 3.48±0.62 | 3.56±0.65 |

| 4. Older than 50 | 3.48±0.82 | 3.50±0.66 | 3.59±0.62 |

| Work experience | |||

| 1. Less than 5 years | 3.69±0.85 | 3.69±0.62 | 3.38±0.52 |

| 2. 5–10 years | 3.50±0.70 | 3.53±0.74 | 3.42±0.65 |

| 3. 10–15 years | 3.58±0.81 | 3.68±0.67 | 3.50±0.74 |

| 4. 15–20 years | 3.30±0.87 | 3.54±0.51 | 3.76±0.48 |

| 5. More than 20 years | 3.18±0.82 | 3.54±0.66 | 3.86±0.62 |

2.3. Data analysis

The entropy weighting method was applied to calculate the weights of the study factors encompassing occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience, which influence the safety performance of healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the influence of demographic variables including age, gender, and work experience was considered.

In the entropy method, the concept of uncertainty is used to determine the weights of the criteria. This method measures the dispersion of a probability distribution; a low entropy value is related to a distribution with a single sharp peak. Lower uncertainty is observed in a sharp distribution than in a broad distribution [62].

The entropy steps are as follows: The decision matrix for the MCDM problem considers m alternatives and n criteria. In the current study, entropy weighting was applied based on demographic variables. This study used three criteria (n = 3): occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience. The number of alternatives was determined based on the number of individuals in each defined group, according to gender, age, and work experience. For example, according to the gender categorization, there were 110 alternatives for the male group and 234 alternatives for the female group (Table 1).

In the decision matrix, () indicates the performance value of the alternative to the criteria [62]. The dimensionless values of were used to obtain the normalized decision matrix (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

Eqs. (2) and (3) were used to determine the entropy values and calculate the degree of divergence of the criteria.

| (2) |

| (3) |

In the final step, Eq. (4) is employed to determine the entropy weight of each criterion.

| (4) |

3. Results

This study aimed to identify the most influential factors affecting healthcare providers’ safety performance during the COVID-19 pandemic by considering demographic variables. The entropy method was applied to determine the weights of three factors (criteria): occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience. The alternatives were the number of individuals in the different groups, defined based on demographic variables.

The results showed that occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience affected healthcare providers’ safety performance differently as a function of the demographic variables. The results of the different steps of computing the entropy values for healthcare providers in the age group 20–30 are presented in Appendix A.

As shown in Fig. 1 , individual resilience was the most important factor influencing healthcare providers’ safety performance in age groups 20–30 and 31–40, with weights of 51 and 44%, respectively. The least influential factor in these age groups was organizational resilience. In age groups 41–50 and greater than 50 years age groups, organizational resilience was the most influential factor influencing the safe performance of healthcare providers, with weights of 42% and 45%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Weights of influential factors considering different age groups.

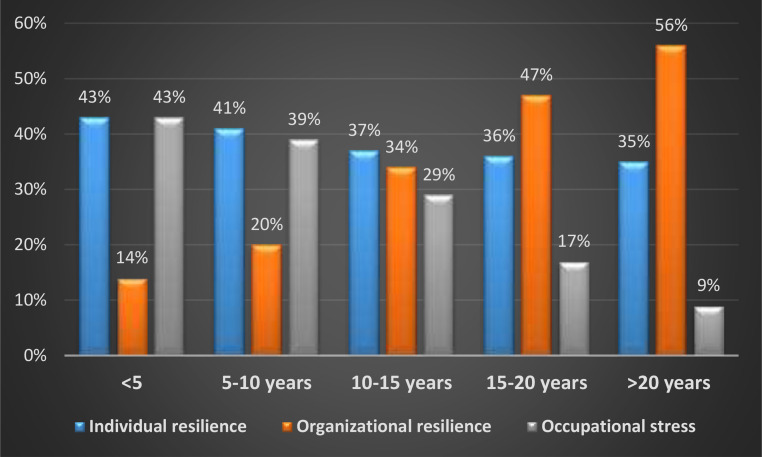

Fig. 2 shows the results of the entropy approach for weighting influential factors on healthcare providers’ safe performance based on their work experience. Individual resilience and occupational stress had greater effects on the safety performance of less-experienced healthcare providers. As shown in Fig. 2, individual resilience and occupational stress, with equal weights of 43%, were the most influential factors in healthcare providers’ safe performance, with work experience of less than five years. These two factors were also the most influential in terms of the safety performance of healthcare providers with 5–10 years of work experience (Fig. 2). The safety performance of experienced healthcare providers was more affected by organizational resilience than by other factors. As illustrated in Fig. 2, organizational resilience influenced healthcare providers’ safety performance for 15–20 and more than 20 years of work experience, with weights of 47% and 56%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Weights of influential factors considering different groups of work experience.

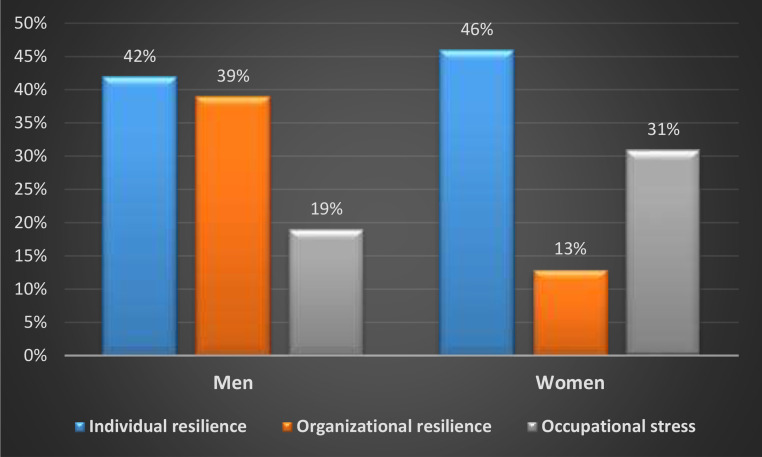

Fig. 3 shows the results of the entropy approach in identifying the most influential factors in healthcare providers’ safety performance considering gender. As illustrated in Fig. 3, individual resilience was the most influential factor in the safety performance of men (42%). They also played the most important role in improving the safety of women (46%). Occupational stress has a considerable influence on the safety performance of women (31%), whereas it has the least influence on that of men (19%). According to the results, individual resilience was the most influential factor in the safety performance of both women and men.

Fig. 3.

Weights of influential factors considering gender differences.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify the influence of occupational stress and resilience-related factors on healthcare providers’ safety performance during the COVID–19 pandemic by using the entropy method and considering the influence of demographic variables.

The findings showed that all study factors, including occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience, could affect healthcare providers’ safety performance under high-pressure work conditions, such as those created during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on these results, demographic variables play a major role in the effects of occupational stress and resilience factors on healthcare providers’ safety performance. In the current study, individual resilience and occupational stress were more important than organizational resilience in younger healthcare workers and had major effects on safety performance. Weitzel et al. [63] indicated that younger participants were more resilient than older ones. The prevalence of high resilience decreases with age. Some workplace stressors, such as high job demands associated with aging, tend to make older workers less resilient in the face of adversity [64]. Marinaccio et al. [65] suggested an association between work-related stress and sociodemographic factors such as age. In a study conducted among doctors in a health service [66]. According to previous studies, there is a correlation between individual resilience and employee safety performance. In addition, it has been suggested that individual resilience negatively impacts psychological stress [20].

In this study, organizational resilience was the most influential factor in the safe performance of older healthcare providers. Organizational- and system-oriented resilience can influence safety performance [35], [67]. This finding supports the previous results of Bose and Pal [68], who reported significant effects of age groups on workplace resilience. Older employees with more work-related experiences are more familiar with workplace settings and can try different coping strategies and select effective ones, which can affect workplace resilience [64]. Organizational resilience and the adaptive response of health services and hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic will help increase the focus on new capacities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergent situations [69]. According to earlier findings, organizations with high levels of resilience have better safety performances [67]. The concept of organizational resilience is related to working life, cultural norms, and effects on worker stress. Building reserves before a crisis, creating workplace cultures, and considering issues such as effective leadership can improve the ability to succeed and successfully adapt during the COVID-19 pandemic and can also lead to improvements in individual resilience [6].

Individual resilience as an innate trait is needed for healthcare providers to manage the levels of anxiety, job stress, and psychological distress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic [6,70]. Additionally, stress management approaches can reduce job burnout and promote resilience in healthcare providers [6]. Individual and organizational resilience in the current study were more influential than occupational stress on the safe performance of healthcare providers with long working experience and those aged 41 years and older. It is difficult to separate age and work experience from healthcare providers’ resilience. The results of the current study echo findings from other studies, such as Zheng et al. [71] who found that resilience scores were higher in older and experienced nurses than in younger nurses.

Gender-based analysis showed that individual resilience plays a major role in promoting safe work performance among both female and male healthcare providers. Afshari et al. [72] reported different levels of individual resilience between male and female nurses. Occupational stress was the second most influential factor from the perspective of female healthcare providers. Earlier work has reported greater levels of work-related stress in female employees than in male employees of an occupational medicine service [73]. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, males reported higher levels of individual resilience and lower levels of stress than females [74]. Based on the opinions of male healthcare providers, organizational resilience is another important factor influencing healthcare providers’ safety performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizational resilience can affect the ability of an organization to respond to unexpected events and maintain system safety in the healthcare sector [69,75].

During crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, individual and organizational resilience can help healthcare systems respond to the crisis, reduce occupational stress, and improve healthcare providers’ safety performance. This may lead to higher productivity and lower error rates among healthcare providers. Managers and safety professionals in the healthcare sector should focus on the critical aspects influencing healthcare providers’ safety performance during a crisis to improve workplace performance and levels of safety in safety-critical sectors. This study also has practical implications for healthcare organizations during adversity. Enhancing organizational resilience, building a resilient workforce, and implementing strategies to reduce occupational stress can help improve coping abilities among healthcare providers when encountering adverse events. In the context of organizational and individual resilience, managers can select skilled and resilient employees. As resilience levels vary among employees of different age groups, managers should consider the specific needs and resources of employees of different ages [76].

5. Study limitations

The current study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design of this study prevented a definitive causal conclusions [20]. Another limitation was the use of self-reported measures. Finally, the study did not consider some important job-related factors such as burnout, job satisfaction, and role overload [40]. Future research might explore the effects of resilience and job-related factors, such as burnout, job satisfaction, and role overload, on healthcare providers’ safety performance during a crisis, as well as the interactive effects of safety climate that shape employees’ perception of safety-related policies and procedures.

6. Conclusions

Different factors might affect healthcare providers’ safety performance during crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This study examined the influence of occupational stress, individual resilience, and organizational resilience on the safety performance of healthcare providers by considering demographic variables. Improving individual and organizational abilities to adapt successfully to adversities can enhance the safety performance of healthcare providers. A questionnaire was designed based on the principles of resilience at the organizational and individual levels, as well as occupational stress. The questionnaire was distributed among healthcare providers at a teaching hospital. The entropy method, an MCDM approach, was employed to examine the effects of age, work experience, and gender. The findings of the entropy method indicate that organizational resilience was the most influential factor in older healthcare providers’ safety performance, whereas individual resilience was important for young healthcare providers. The outcomes associated with work experience revealed that individual resilience was the most influential factor in the safe performance of less experienced healthcare providers. A gender-based analysis showed that individual resilience was the most influential factor in the safe performance of both female and male healthcare providers. The findings of this study can assist the healthcare sector in overcoming adversities and unexpected events during pandemics. These findings may be used to promote safe performance among healthcare providers of different ages, sexes, and levels of work experience during a pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that may have influenced the work reported in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all healthcare staff who participated in this study. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Health and Environment Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences [Grant No. 65558; ethical code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.617].

Appendix A. The results of the entropy method for healthcare workers in the age group 20–30

| Alternative no. | Individual resilience | Organizational resilience | Occupational stress | Normalized matrix | Computing entropy value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.50 | 3.75 | 3.67 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.057 | −0.002 | −0.044 |

| 14 | 3.33 | 3.75 | 3.67 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.056 | −0.002 | −0.044 |

| 21 | 4.50 | 4.31 | 3.50 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.008 | −0.081 | −0.005 | −0.045 |

| 26 | 3.50 | 3.31 | 3.17 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.057 | −0.001 | −0.046 |

| 31 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 4.17 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.057 | −0.001 | −0.043 |

| 32 | 3.00 | 2.63 | 3.67 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.008 | −0.055 | 0.002 | −0.044 |

| 35 | 3.33 | 3.44 | 4.33 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.006 | −0.056 | −0.001 | −0.042 |

| 36 | 3.00 | 2.88 | 3.33 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.008 | −0.055 | 0.001 | −0.045 |

| 37 | 4.17 | 3.50 | 2.17 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.013 | −0.090 | −0.001 | −0.052 |

| 39 | 2.50 | 2.69 | 4.33 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | −0.043 | 0.002 | −0.042 |

| 40 | 4.00 | 3.19 | 3.00 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.089 | 0.000 | −0.047 |

| 41 | 5.00 | 4.56 | 3.83 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.007 | −0.103 | −0.005 | −0.044 |

| 42 | 3.33 | 2.69 | 4.00 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.007 | −0.056 | 0.002 | −0.043 |

| 43 | 2.83 | 4.00 | 2.50 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.011 | −0.044 | −0.003 | −0.050 |

| 45 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 3.33 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.008 | −0.068 | 0.001 | −0.045 |

| 46 | 2.67 | 1.81 | 3.67 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.008 | −0.044 | 0.006 | −0.044 |

| 48 | 2.83 | 3.50 | 3.67 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.044 | −0.001 | −0.044 |

| 49 | 3.17 | 3.00 | 3.17 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.009 | −0.056 | 0.001 | −0.046 |

| 50 | 3.17 | 3.56 | 2.33 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.012 | −0.056 | −0.002 | −0.051 |

| 51 | 3.50 | 3.38 | 2.50 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.011 | −0.077 | −0.001 | −0.050 |

| 54 | 4.33 | 3.31 | 3.17 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.080 | −0.001 | −0.046 |

| 58 | 2.50 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.043 | −0.003 | −0.043 |

| 59 | 2.67 | 3.69 | 4.00 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.044 | −0.002 | −0.043 |

| 60 | 4.33 | 4.38 | 4.67 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.006 | −0.080 | −0.005 | −0.041 |

| 61 | 3.33 | 3.13 | 3.33 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.056 | 0.000 | −0.045 |

| 62 | 4.00 | 3.69 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.079 | −0.002 | −0.043 |

| 63 | 3.83 | 3.63 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.068 | −0.002 | −0.043 |

| 65 | 4.00 | 3.19 | 4.17 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.079 | 0.000 | −0.043 |

| 69 | 3.00 | 3.81 | 2.67 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.010 | −0.045 | −0.003 | −0.049 |

| 72 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.83 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.068 | −0.001 | −0.044 |

| 75 | 4.33 | 4.38 | 5.00 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.006 | −0.080 | −0.005 | −0.041 |

| 76 | 2.17 | 4.06 | 3.50 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.008 | −0.042 | −0.004 | −0.045 |

| 77 | 2.00 | 4.44 | 3.17 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.009 | −0.041 | −0.005 | −0.046 |

| 78 | 2.83 | 4.38 | 3.17 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.009 | −0.054 | −0.004 | −0.046 |

| 79 | 3.67 | 2.75 | 4.67 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.006 | −0.068 | 0.002 | −0.041 |

| 85 | 3.67 | 3.19 | 3.83 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.068 | 0.000 | −0.044 |

| 89 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 4.50 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.006 | −0.045 | −0.003 | −0.042 |

| 90 | 4.33 | 4.25 | 4.17 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.070 | −0.004 | −0.043 |

| 94 | 3.00 | 4.13 | 3.17 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.009 | −0.045 | −0.004 | −0.046 |

| 95 | 3.67 | 3.06 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.066 | 0.000 | −0.043 |

| 96 | 3.33 | 3.13 | 3.17 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.046 | 0.000 | −0.046 |

| 99 | 2.33 | 3.69 | 3.50 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.042 | −0.002 | −0.045 |

| 100 | 4.00 | 3.31 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.079 | −0.001 | −0.043 |

| 103 | 4.17 | 3.13 | 4.00 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.080 | 0.000 | −0.043 |

| 105 | 3.67 | 3.06 | 3.83 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.068 | 0.000 | −0.044 |

| 106 | 3.67 | 3.31 | 3.33 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.068 | −0.001 | −0.045 |

| 107 | 4.67 | 4.50 | 4.83 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.006 | −0.081 | −0.004 | −0.041 |

| 111 | 4.67 | 4.50 | 4.83 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.006 | −0.081 | −0.004 | −0.041 |

| 113 | 3.67 | 2.25 | 3.50 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.008 | −0.068 | 0.004 | −0.045 |

| 116 | 4.33 | 4.13 | 4.50 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.006 | −0.040 | −0.004 | −0.042 |

| 122 | 3.67 | 2.88 | 4.17 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.068 | 0.001 | −0.043 |

| 123 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.83 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.057 | −0.001 | −0.044 |

| 124 | 3.50 | 3.13 | 3.00 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.057 | 0.000 | −0.047 |

| 127 | 1.67 | 2.69 | 4.67 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.006 | −0.029 | 0.002 | −0.041 |

| 139 | 4.00 | 3.63 | 3.50 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.079 | −0.002 | −0.045 |

| 141 | 3.33 | 2.06 | 3.17 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.009 | −0.056 | 0.004 | −0.046 |

| 142 | 4.00 | 4.06 | 4.17 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.079 | −0.003 | −0.043 |

| 145 | 3.67 | 3.63 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.078 | −0.002 | −0.043 |

| 147 | 2.83 | 3.06 | 2.83 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.010 | −0.034 | 0.000 | −0.048 |

| 148 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.089 | −0.003 | −0.043 |

| 149 | 4.00 | 3.44 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.089 | −0.001 | −0.043 |

| 152 | 5.00 | 3.81 | 1.83 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.015 | −0.103 | −0.003 | −0.056 |

| 155 | 3.50 | 3.44 | 3.50 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.057 | −0.001 | −0.045 |

| 156 | 3.33 | 3.44 | 3.33 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.056 | −0.001 | −0.045 |

| 157 | 3.17 | 2.69 | 3.33 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.008 | −0.046 | 0.002 | −0.045 |

| 158 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.089 | −0.003 | −0.043 |

| 159 | 4.00 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.089 | −0.001 | −0.043 |

| 160 | 3.00 | 3.38 | 3.50 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.045 | −0.001 | −0.045 |

| 162 | 4.00 | 3.81 | 3.17 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | −0.089 | −0.003 | −0.046 |

| 164 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.17 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.089 | −0.003 | −0.043 |

| 166 | 4.67 | 4.63 | 4.17 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.007 | −0.091 | −0.005 | −0.043 |

| 171 | 4.00 | 4.06 | 4.00 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.089 | −0.004 | −0.043 |

| 183 | 4.67 | 4.50 | 3.50 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.008 | −0.091 | −0.004 | −0.045 |

| 188 | 2.50 | 3.56 | 2.33 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.012 | −0.043 | −0.002 | −0.051 |

| 192 | 4.67 | 4.88 | 4.83 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.006 | −0.091 | −0.005 | −0.041 |

| 193 | 3.67 | 3.94 | 3.17 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | −0.068 | −0.003 | −0.046 |

| 194 | 3.67 | 3.69 | 3.33 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.068 | −0.002 | −0.045 |

| 195 | 3.50 | 3.56 | 3.50 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.057 | −0.002 | −0.045 |

| 197 | 3.83 | 3.75 | 4.33 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.006 | −0.068 | −0.002 | −0.042 |

| 198 | 4.00 | 4.25 | 4.33 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.006 | −0.089 | −0.004 | −0.042 |

| 199 | 2.50 | 2.69 | 3.83 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | −0.043 | 0.002 | −0.044 |

| 200 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.00 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.045 | 0.000 | −0.047 |

| 201 | 4.00 | 3.19 | 4.33 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.006 | −0.079 | 0.000 | −0.042 |

| 202 | 2.67 | 3.69 | 3.17 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.009 | −0.044 | −0.002 | −0.046 |

| 205 | 4.33 | 3.31 | 3.17 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.080 | −0.001 | −0.046 |

| 208 | 2.17 | 3.06 | 3.83 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.032 | 0.000 | −0.044 |

| 212 | 3.50 | 4.13 | 2.83 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.010 | −0.057 | −0.003 | −0.048 |

| 214 | 3.83 | 3.25 | 2.00 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.014 | −0.068 | 0.000 | −0.054 |

| 222 | 3.00 | 3.44 | 2.33 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.012 | −0.055 | −0.001 | −0.051 |

| 226 | 4.17 | 2.81 | 1.00 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.028 | −0.090 | 0.001 | −0.071 |

| 227 | 4.17 | 2.81 | 2.67 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.010 | −0.080 | 0.001 | −0.049 |

| 230 | 3.17 | 3.94 | 3.33 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.056 | −0.003 | −0.045 |

| 234 | 4.50 | 3.31 | 3.67 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.071 | −0.001 | −0.044 |

| 239 | 3.67 | 2.63 | 2.33 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.012 | −0.068 | 0.002 | −0.051 |

| 242 | 4.33 | 3.25 | 3.83 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.007 | −0.080 | 0.000 | −0.044 |

| 243 | 4.00 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.079 | −0.001 | −0.044 |

| 260 | 3.83 | 4.19 | 4.33 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.006 | −0.068 | −0.004 | −0.042 |

| 267 | 3.83 | 3.88 | 4.83 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.006 | −0.058 | −0.003 | −0.041 |

| 272 | 4.00 | 4.13 | 4.50 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.006 | −0.089 | −0.004 | −0.042 |

| 281 | 3.33 | 3.81 | 2.50 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.011 | −0.046 | −0.003 | −0.050 |

| 283 | 4.17 | 3.50 | 4.33 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.006 | −0.090 | −0.001 | −0.042 |

| 287 | 4.33 | 4.25 | 3.83 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.086 | −0.004 | −0.043 |

| 289 | 3.83 | 3.88 | 3.83 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.007 | −0.068 | −0.003 | −0.043 |

| 290 | 3.00 | 3.31 | 3.17 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.009 | −0.055 | −0.001 | −0.046 |

| 292 | 2.83 | 3.81 | 4.33 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.006 | −0.054 | −0.002 | −0.042 |

| 293 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.17 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.007 | −0.079 | −0.002 | −0.043 |

| 294 | 3.67 | 3.31 | 2.00 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.014 | −0.068 | −0.001 | −0.053 |

| 300 | 3.50 | 3.44 | 3.67 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | −0.065 | −0.001 | −0.044 |

| 325 | 3.83 | 3.75 | 2.50 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.011 | −0.068 | −0.002 | −0.050 |

| 334 | 2.50 | 2.69 | 4.00 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | −0.055 | 0.002 | −0.043 |

| 335 | 4.17 | 3.75 | 2.00 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.014 | −0.090 | −0.002 | −0.054 |

| 336 | 3.67 | 3.19 | 2.33 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.012 | −0.068 | 0.000 | −0.051 |

| 337 | 5.00 | 4.75 | 3.17 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.009 | −0.100 | −0.004 | −0.045 |

| 338 | 3.67 | 2.56 | 2.17 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.013 | −0.068 | 0.002 | −0.052 |

| 339 | 4.00 | 3.75 | 2.83 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.010 | −0.089 | −0.002 | −0.048 |

| 340 | 2.83 | 2.63 | 2.17 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.013 | −0.043 | 0.002 | −0.052 |

| 343 | 4.00 | 3.25 | 1.83 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.015 | −0.089 | 0.000 | −0.056 |

| 344 | 4.17 | 2.69 | 3.83 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.007 | −0.090 | 0.002 | −0.044 |

| −7.874 | −0.166 | −5.353 | |||||||

| m | 118 | ||||||||

| k | 0.483 | −3.800 | −0.080 | −2.584 | |||||

| 4.800 | 1.080 | 3.584 | |||||||

| 9.465 | |||||||||

| Weights | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.38 | ||||||

References

- 1.Omidi L., Moradi G., Sarkari N.M. Risk of COVID-19 infection in workplace settings and the use of personal protective equipment. Work. 2020;66:377–378. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–-11 March 2020 https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (2020). Accessed 23 June 20210.

- 3.Vahidy F., Jones S.L., Tano M.E., Nicolas J.C., Khan O.A., Meeks J.R., Pan A.P., Menser T., Sasangohar F., Naufal G. Rapid response to drive COVID-19 research in a learning health care system: rationale and design of the houston methodist COVID-19 surveillance and outcomes registry (CURATOR) JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9:e26773. doi: 10.2196/26773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X., Hegde S., Son C., Keller B., Smith A., Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e22817. doi: 10.2196/22817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Son C., Hegde S., Smith A., Wang X., Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: interview survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath C., Sommerfield A., von Ungern-Sternberg B. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1364–1371. doi: 10.1111/anae.15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasangohar F., Jones S.L., Masud F.N., Vahidy F.S., Kash B.A. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. Anesth. Analg. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krystal J.H., McNeil R.L. Responding to the hidden pandemic for healthcare workers: stress. Nat. Med. 2020;26:639. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jalili M., Niroomand M., Hadavand F., Zeinali K., Fotouhi A. Burnout among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01695-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moradi S., Farahnaki Z., Akbarzadeh A., Gharagozlou F., Pournajaf A., Abbasi A.M., Omidi L., Hami M., Karchani M. Relationship between shift work and Job satisfaction among nurses: a Cross-sectional study. Int. J. Hosp. Res. 2014;3:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omidi L., Zakerian S.A., Saraji J.N., Hadavandi E., Yekaninejad M.S. Safety performance assessment among control room operators based on feature extraction and genetic fuzzy system in the process industry. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018;116:590–602. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park Y.M., Kim S.Y. Impacts of job stress and cognitive failure on patient safety incidents among hospital nurses. Saf. Health Work. 2013;4:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itzhaki M., Peles-Bortz A., Kostistky H., Barnoy D., Filshtinsky V., Bluvstein I. Exposure of mental health nurses to violence associated with job stress, life satisfaction, staff resilience, and post-traumatic growth. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015;24:403–412. doi: 10.1111/inm.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tajvar A., Saraji G.N., Ghanbarnejad A., Omidi L., Hosseini S.S.S., Abadi A.S.S. Occupational stress and mental health among nurses in a medical intensive care unit of a general hospital in Bandar Abbas in 2013. Electron Physician. 2015;7:1108. doi: 10.14661/2015.1108-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conway P., Campanini P., Sartori S., Dotti R., Costa G. Main and interactive effects of shiftwork, age and work stress on health in an Italian sample of healthcare workers. Appl. Ergon. 2008;39:630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker D.F., DeCotiis T.A. Organizational determinants of job stress. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1983;32:160–177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mealer M., Jones J., Newman J., McFann K.K., Rothbaum B., Moss M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: results of a national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012;49:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu F., Raphael D., Mackay L., Smith M., King A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019;93:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y., McCabe B., Hyatt D. Impact of individual resilience and safety climate on safety performance and psychological stress of construction workers: a case study of the Ontario construction industry. J. Saf. Res. 2017;61:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salehi V., Veitch B. Measuring and analyzing adaptive capacity at management levels of resilient systems. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020;63 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakhshi M., Omidi L., Omidi K., Moradi G., Mayofpour F., Darvishi T. Measuring hospital resilience in emergency situations and examining the knowledge and attitude of emergency department staff toward disaster management. J. Saf. Promot. Inj. Prev. 2020;8 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connor K.M., Davidson J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress. Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Trauma. Stress Studs. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lengnick-Hall C.A., Beck T.E., Lengnick-Hall M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011;21:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S.H. Construction of an early risk warning model of organizational resilience: an empirical study based on samples of R&D teams. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2016;2016 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duchek S. Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020;13:215–246. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omidi L., Karimi H., Mousavi S., Moradi G. The mediating role of safety climate in the relationship between organizational resilience and safety performance. J. Health Saf. Work. 2022;12:536–548. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riolli L., Savicki V. Information system organizational resilience. Omega. 2003;31:227–233. (Westport) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stiles S., Golightly D., Ryan B. Impact of COVID-19 on health and safety in the construction sector. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hfm.20882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azadeh A., Salehi V., Ashjari B., Saberi M. Performance evaluation of integrated resilience engineering factors by data envelopment analysis: the case of a petrochemical plant. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2014;92:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollnagel E., Nemeth C.P., Dekker S. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.; 2008. Resilience Engineering perspectives: Remaining Sensitive to the Possibility of Failure. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furniss D., Back J., Blandford A., Hildebrandt M., Broberg H. A resilience markers framework for small teams. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011;96:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollnagel E. Taylor & Francis; 2017. Safety-II in Practice: Developing the Resilience Potentials. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peñaloza G.A., Saurin T.A., Formoso C.T., Herrera I.A. A resilience engineering perspective of safety performance measurement systems: a systematic literature review. Saf. Sci. 2020;130 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabbani M., Yazdanparast R., Mobini M. An algorithm for performance evaluation of resilience engineering culture based on graph theory and matrix approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2019;10:228–241. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taghi-Molla A., Rabbani M., Gavareshki M.H.K., Dehghani E. Safety improvement in a gas refinery based on resilience engineering and macro-ergonomics indicators: a Bayesian network–artificial neural network approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2020:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neal A., Griffin M.A. Safety climate and safety behaviour. Aust. J. Manag. 2002;27:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalteh H.O., Mortazavi S.B., Mohammadi E., Salesi M. The relationship between safety culture and safety climate and safety performance: a systematic review. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021;27:206–216. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2018.1556976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salehi V., Veitch B. Performance optimization of integrated job-driven and resilience factors by means of a quantitative approach. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020;78 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajabi F., Mokarami H., Jahangiri M. Investigation of safety performance of the workers and the effective demographic charactristics in a gas refinery. J. Occup. Hyg. Eng. 2019;6:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng X., Chan A.H. Demographic influences on safety consciousness and safety citizenship behavior of construction workers. Saf. Sci. 2020;129 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreira R.J., Buttell F., Cannon C. COVID-19: immediate predictors of individual resilience. Sustainability. 2020;12:6495. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Said R.M., El-Shafei D.A. Occupational stress, job satisfaction, and intent to leave: nurses working on front lines during COVID-19 pandemic in Zagazig City, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28:8791–8801. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peiffer-Smadja N., Lucet J.C., Bendjelloul G., Bouadma L., Gerard S., Choquet C., Jacques S., Khalil A., Maisani P., Casalino E. Challenges and issues about organizing a hospital to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak: experience from a French reference centre. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26:669–672. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruk M.E., Myers M., Varpilah S.T., Dahn B.T. What is a resilient health system? lessons from Ebola. Lancet North Am. Ed. 2015;385:1910–1912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hollnagel E. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd; 2013. Resilience Engineering in practice: A guidebook. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Omidi L., Dolatabad K.M., Pilbeam C. Differences in perception of the importance of process safety indicators between experts in Iran and the West. J. Saf. Res. 2023:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hussain S.A.I., Mandal U.K. Proceedings of the National Level Conference on Engineering Problems and Application of Mathematics. 2016. Entropy based MCDM approach for Selection of material; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shannon C.E., Weaver W. University of Illinois Press; Urbana: 1949. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delgado A. Proceedings of the IEEE XXIV International Conference on Electronics, Electrical Engineering and Computing (INTERCON) IEEE; 2017. Social conflict analysis on a mining project using shannon entropy; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salehi V., Zarei H., Shirali G.A., Hajizadeh K. An entropy-based TOPSIS approach for analyzing and assessing crisis management systems in petrochemical industries. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020;67 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner N., Tucker S., Kelloway E.K. Prevalence and demographic differences in microaccidents and safety behaviors among young workers in Canada. J. Saf. Res. 2015;53:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siu O.I., Phillips D.R., Leung T.W. Age differences in safety attitudes and safety performance in Hong Kong construction workers. J. Saf. Res. 2003;34:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4375(02)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maitiniyazi S., Canavari M. Understanding Chinese consumers' safety perceptions of dairy products: a qualitative study. Br. Food J. 2021;123:1837–1852. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boddy C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2016;19:426–432. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Omidi L., Salehi V., Zakerian S., Nasl Saraji J. Assessing the influence of safety climate-related factors on safety performance using an Integrated Entropy-TOPSIS Approach. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2022;39:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moradi G., Omidi L., Vosoughi S., Ebrahimi H., Alizadeh A., Alimohammadi I. Effects of noise on selective attention: the role of introversion and extraversion. Appl. Acoust. 2019;146:213–217. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Omidi L., Mousavi S., Moradi G., Taheri F. Traffic climate, driver behaviour and dangerous driving among taxi drivers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2021.1903705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Damiri H., Neisi A., Arshadi N. The study of relationship between job stress and general health: considering the moderating role of perceived organizational support in employees of oil company. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Stud. 2014;1:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rezaeipandari H., Mohammadpoorasl A., Morowatisharifabad M.A., Shaghaghi A. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of abridged Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 (CD-RISC-10) among older adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:493. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moradian M., Modanloo V., Aghaiee S. Comparative analysis of multi criteria decision making techniques for material selection of brake booster valve body. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. Engl. Ed. 2019;6:526–534. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weitzel E.C., Löbner M., Röhr S., Pabst A., Reininghaus U., Riedel-Heller S.G. Prevalence of high resilience in old age and association with perceived threat of covid-19—Results from a representative survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:7173. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18137173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.King R., Jex S. Emerald Group Publishing Limited2014; 2023. Age, resilience, well-being, and Positive Work outcomes, The role of Demographics in Occupational Stress and Well Being; pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marinaccio A., Ferrante P., Corfiati M., Di Tecco C., Rondinone B.M., Bonafede M., Ronchetti M., Persechino B., Iavicoli S. The relevance of socio-demographic and occupational variables for the assessment of work-related stress risk. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swanson V., Power K., Simpson R. A comparison of stress and job satisfaction in female and male GPs and consultants. Stress Med. 1996;12:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wehbe F., Al Hattab M., Hamzeh F. Exploring associations between resilience and construction safety performance in safety networks. Saf. Sci. 2016;82:338–351. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bose S., Pal D. Impact of employee demography, family responsibility and perceived family support on workplace resilience. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020;21:1249–1262. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bryce C., Ring P., Ashby S., Wardman J. Resilience in the face of uncertainty: early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Risk Res. 2020;23:880–887. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Setiawati Y., Wahyuhadi J., Joestandari F., Maramis M.M., Atika A. Anxiety and resilience of healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021;14:1. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S276655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng Z., Gangaram P., Xie H., Chua S., Ong S.B.C., Koh S.E. Job satisfaction and resilience in psychiatric nurses: a study at the institute of mental health, singapore. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017;26:612–619. doi: 10.1111/inm.12286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Afshari D., Nourollahi-Darabad M., Chinisaz N. Demographic predictors of resilience among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vigna L., Brunani A., Brugnera A., Grossi E., Compare A., Tirelli A.S., Conti D.M., Agnelli G.M., Andersen L.L., Buscema M. Determinants of metabolic syndrome in obese workers: gender differences in perceived job-related stress and in psychological characteristics identified using artificial neural networks. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2019;24:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0536-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yan S., Xu R., Stratton T.D., Kavcic V., Luo D., Hou F., Bi F., Jiao R., Song K., Jiang Y. Sex differences and psychological stress: responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in China. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10085-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salehi V., Hanson N., Smith D., McCloskey R., Jarrett P., Veitch B. Modeling and analyzing hospital to home transition processes of frail older adults using the functional resonance analysis method (FRAM) Appl. Ergon. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang F., Cao L. Linking employee resilience with organizational resilience: the roles of coping mechanism and managerial resilience. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021:1063–1075. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S318632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]