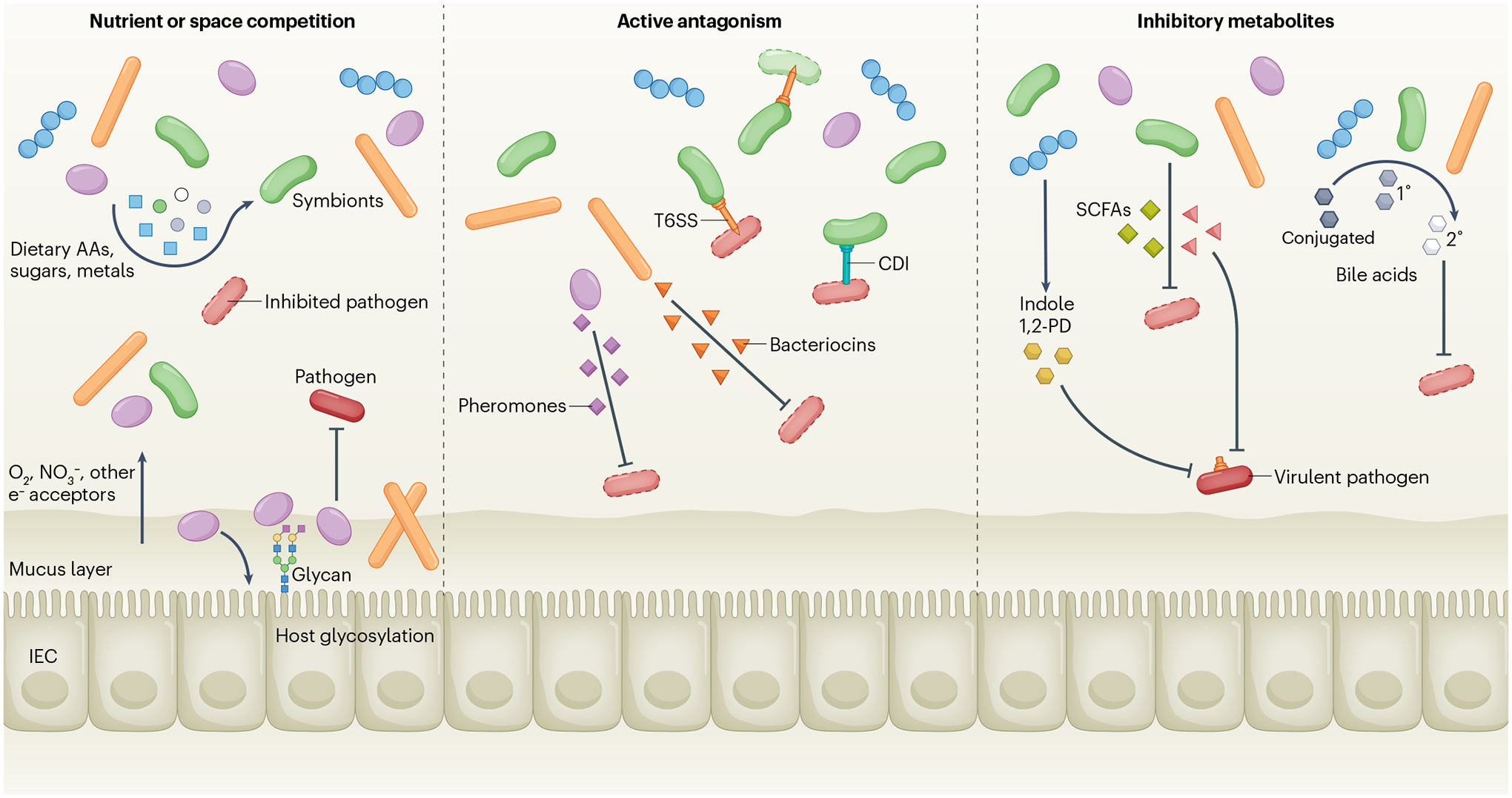

Fig. 1 |. Direct mechanisms of colonization resistance.

Native symbiotic bacteria consume dietary amino acids (AAs), sugars, metals and respiratory electron acceptors such as O2 and NO3−, thus starving the pathogen of essential nutrients and molecules (left panel). At the epithelial surface, bacteria can modify host glycosylation and/or use it as a nutrient for adhesion, creating a new microscopic niche that blocks pathogen access to the epithelium. Other symbionts adhering to sites on the epithelium or in the mucus can also prevent pathogen access. Symbionts can also directly kill pathogens via contact-dependent inhibition (CDI), the type VI secretion system (T6SS) or secreted molecules, including bacteriocins or pheromone peptides (centre panel). Other inhibitory compounds such as acetic, butyric or propionic acids (short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)), indole or 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD) are secreted by the microbiota and inhibit growth or suppress virulence factor expression in pathogens (right panel). Many symbionts can modify bile acids by deconjugation, whereas some (for example, Clostridium scindens) can convert primary to secondary bile acids that inhibit pathogen growth. IEC, intestinal epithelial cell.