Abstract

Background

Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS) is an acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy rarely observed during pregnancy.

Methods

In this retrospective study, we analyzed the characteristics of pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) diagnosed in French University Hospitals in the 2002–2022 period and compared them with a reference group of same-age non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS) identified in the same institutions & timeframe.

Results

We identified 16 pGBS cases. Median age was 31 years (28–36), and GBS developed in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimester in 31%, 31% and 38% of cases respectively. A previous infection was identified in six cases (37%), GBS was demyelinating in nine cases (56%), and four patients (25%) needed respiratory assistance. Fifteen patients (94%) were treated with intravenous immunoglobulins, and neurological recovery was complete in all cases (100%). Unscheduled caesarean section was needed in five cases (31%), and two fetuses (12.5%) died because of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection (1 case) and HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets) syndrome (1 case). In comparison with a reference group of 18 npGBS women with a median age of 30 years (27–33), pGBS patients more frequently had CMV infection (31% vs 11%), had a prolonged delay between GBS onset and hospital admission (delay > 7 days: 57% vs 12%), more often needed ICU admission (56% vs 33%) and respiratory assistance (25% vs 11%), and more often presented with treatment-related fluctuations (37% vs 0%).

Conclusions

This study shows GBS during pregnancy is a severe maternal condition with significant fetal mortality.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00415-023-11808-w.

Keywords: Guillain-Barré syndrome, Pregnancy, Cytomegalovirus

Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute peripheral nervous system (PNS) inflammatory disorder characterized by acute areflexic paralysis, increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein content, and demyelinating or axonal abnormalities on electrodiagnostic studies (EDX) [1]. GBS is a life-threatening disorder with a 3–7% mortality rate in western countries, and treatment is based on general care, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) and/or plasma exchanges (PE) [1].

GBS is rarely observed during pregnancy and the management of pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) is not well established. Medical literature on the subject is contradictory, with some reports suggesting significant pGBS maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, and other reports suggesting no significant maternal and fetal complications [2–5]. Importantly, many of these cases were published before the 1980s, at a time when active treatments, i.e., IVIg and PE, and modern intensive care support were not available [5]. Similarly, recent cases have been reported in countries where active treatments and detailed paraclinical investigations are unavailable [2–4]. As a result, there is a need for relevant data on pGBS clinical, biological, electrophysiological, treatment response and outcome characteristics [2–5].

In this context, as detailed data on pGBS is lacking, we performed a study to analyze pGBS frequency, clinical and paraclinical presentation, treatment response, and maternal and fetal outcome. We conducted a retrospective nationwide study in which we analyzed the clinical and paraclinical characteristics of patients with pGBS diagnosed in the 2002–2022 timeframe in France and compared these patients with a reference group of same-age non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS) identified in the same institutions and timeframe. Our aim was to obtain a detailed picture of pGBS to provide clinicians with relevant tools for improving pGBS management.

Patients and methods

Patients

We performed a retrospective nationwide observational study including pregnant female patients with age > 18 years diagnosed with GBS between 2002 and 2022 in French University Hospitals. GBS diagnosis was based on standard clinical, CSF and EDX criteria [1]. Neurologists from the 25 largest French University Hospitals were contacted, and clinical, paraclinical, and treatment data from pregnant women with GBS were collected from medical records by referring physicians. Therapeutic responses were evaluated by the referring neurologists according to the practice of each center. Given that our study was conducted retrospectively on documented patient records with no specific intervention of any kind, local ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

Neurological data

Modified Erasmus GBS Outcome Score (mEGOS), Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS), and GBS Disability Score (GBS-DS) were recorded if available [6–8]. The mEGOS score correlates with the risk of being unable to walk unaided at 4 and 26 weeks, the EGRIS score estimates the risk of respiratory failure within the first week, and the GBS-DS scale assesses the functional status of GBS patients. Data on Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, ICU complications, respiratory assistance and mechanical ventilation were also retrieved. GBS treatment-related fluctuations (TRF), GBS relapses, and progression towards chronic inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) were also retrieved. A TRF was defined as a GBS clinical worsening occurring less than 8 weeks after treatment-induced clinical improvement or stabilization [1]. A GBS relapse was defined as a new GBS episode occurring more than 2 months after the first GBS episode if recovery was complete after the first GBS episode, or a new GBS episode occurring more than 4 months after the first GBS episode if recovery was incomplete after the first GBS episode [1]. Acute-onset CIDP was considered in patients presenting with three or more TRFs and/or presenting with clinical worsening more than 8 weeks after disease onset [1]. Data gathering was performed between November 2021 and March 2022.

Electrodiagnostic (EDX) studies

EDX studies were done using conventional equipment and standard methods and were performed by a local trained neurologist in all cases. EDX studies included upper and lower limbs nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography using a concentric needle electrode in at least two muscles. Skin temperature was kept in the 32–34 °C range. Demyelination was defined using standard criteria, including motor distal latency prolongation, reduction of motor conduction velocity, prolongation of F-wave latency, absent F-waves, motor conduction block, abnormal temporal dispersion, and distal Compound Muscle Action potential (CMAP) duration prolongation [9].

Paraclinical investigations

CSF content, serum antiganglioside antibodies, and serum bacteria and virus serology were investigated using standard methods. Primary cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was defined by seroconversion during pregnancy, and secondary CMV infection was defined by reactivation of a latent infection [10]. When maternal pre-GBS CMV serology was negative, diagnosis of CMV primary infection was made by detecting anti-CMV specific IgG antibodies in serum [10]. When maternal pre-GBS CMV serology was positive, diagnosis of CMV reactivation was based on the identification of high-avidity anti-CMV IgG antibodies in serum [10].

Obstetrical and child data

Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum, and child psychomotor development-related data were also retrieved, including pregnancy trimester, pregnancy complications, delivery term, delivery anesthesia (local, general, or none), delivery mode (vaginal or cesarean), 5-min APGAR score, newborn ICU admission, postpartum maternal complications, and long-term child psychomotor development.

Comparing pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) and a control group of non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS)

We compared the clinical and paraclinical characteristics of pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) with a control group of non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS). Women from the npGBS group were recruited in the same University Hospitals and same timeframe than pGBS cases to obtain two groups as close as possible in terms of diagnosis and treatment. For instance, if a pGBS woman diagnosed and treated at Bicêtre Hospital in 2010 was included in our series, then a npGBS woman diagnosed and treated at Bicêtre Hospital in 2010 was included as a control. Quantitative variables were investigated using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test and Student’s t-test, and qualitative variables were investigated using chi-squared and Fisher tests. Two-tailed tests were used with significance level set to 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Microsoft Excel Software and BiostaTgv.

Data availability statement

All data and related files from this study are available on request to qualified researchers with no time limit, and subject to a standard data-sharing agreement.

Results

Pregnant women with GBS

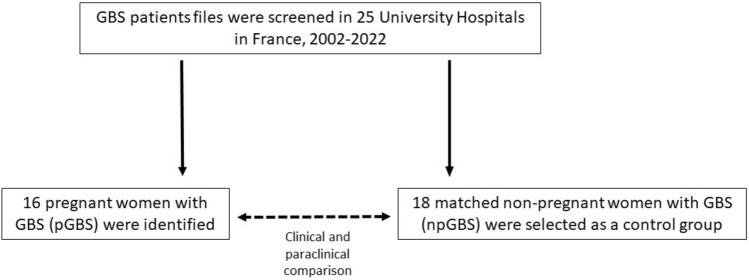

Sixteen pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) were identified in 10 University Hospitals in the 2002–2022 timeframe (Fig. 1). Below, we detail the epidemiological, clinical, EDX, paraclinical, treatment and outcome characteristics of this group of 16 women with pGBS.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. GBS Guillain-Barré syndrome, npGBS non-pregnant women with GBS, pGBS pregnant women with GBS

Neurological characteristics of 16 pregnant women with GBS

Clinical characteristics of this group of 16 patients with pGBS are detailed in Table 1. Median age was 31 years (28–36), and GBS occurred during 1st trimester, 2nd trimester and 3rd trimester in 31%, 31%, and 38% of cases respectively. Mean interval between symptoms onset and hospital admission was 9 days (1–19), and eight patients (50%) were admitted more than 7 days after symptoms onset. When admitted, all patients presented with symmetric neurological symptoms, including limb weakness (93% of cases), sensory symptoms (87%), and abolished tendon reflexes (87%). Seven patients (43%) presented with cranial nerve involvement, including seven cases with facial palsy (43%), and four with bulbar failure, i.e., dysphonia, dysphagia, and dyspnea. At nadir, twelve patients (75%) had cranial nerve involvement, nine patients (56%) were admitted in ICU and four patients (25%) needed mechanical ventilation. No GBS variants such as Miller-Fisher syndrome were observed. Fifteen patients (93%) were treated with standard IVIg courses of 2 g/kg in 2–5 days, three (19%) with PE, and mean time from symptoms onset to treatment was 11 days. Ten patients (62%) had at least two lines of treatment: seven had repeated IVIg infusions, three had successive IVIg and PE, and one had successive IVIg and corticosteroids (CTX). Six patients (37%) presented with TRF. No significant adverse effects were observed with IVIg, PE, and CTX. GBS relapse and CIDP were not observed. Mean mEGOS score at admission was 4 and mean first week EGRIS score was 2.7. At nadir, fourteen patients (88%) had a GBS-DS score ≥ 4, i.e., bedridden or in a wheelchair. GBS-DS scores at discharge were available in 13 cases: five women (38%) had no symptoms (GBS-DS = 0), seven women (53%) presented with minor sensory symptoms and were able to run (GBS-DS = 1), and one woman was able to walk ≥ 10 m without assistance but unable to run (GBS-DS = 2).

Table 1.

A comparison of the clinical characteristics of a group of 16 pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) and a control group of 18 non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS)

| pGBS, n = 16 | npGBS, n = 18 | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 31 (28–36) | 30 (27–33) |

| At admission | ||

| Limb weakness | 15 (93%) | 13 (72%) |

| Areflexia | 14 (87%) | 13 (72%) |

| Sensory symptoms | 14 (87%) | 16 (88%) |

| Symmetric symptoms | 14 (87%) | 13 (72%) |

| Cranial nerve involvement | 7 (43%) | 3 (16%) |

| Mean delay between GBS onset and admission (days)a | 9 | 6 |

| Delay between GBS onset and admission > 7 days | 8 (57%) | 2 (12%)* |

| Mean mEGOS score | 4.1 ± 3 | 1.1 ± 2* |

| Mean EGRIS score | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.2 |

| At nadir | ||

| Cranial nerve involvement | 12 (75%) | 9 (52%) |

| Autonomic dysfunction | 6 (37%) | 4 (22%) |

| ICU admission | 9 (56%) | 6 (33%) |

| Respiratory assistance | 4 (25%) | 2 (11%) |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment | 15 (93%) | 17 (94%) |

| Patients with ≥ 2 treatmentsb | 10 (62%) | 2 (11%)* |

| Treatment-related fluctuationsc | 6 (37%) | 0* |

| Mean GBS-DS | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 1 |

| Long-term outcome | ||

| Relapse | 0 | 0 |

| Mean GBS-DS score 6 months after GBS onset | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.5 |

Data are given as n (%), median, and means ± SD

Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding

CTX corticosteroids, EGRIS Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score, GBS Guillain–Barré syndrome, GBS-DS GBS Disability Score, ICU Intensive Care Unit, IVIg intravenous immunoglobulin, mEGOS Modified Erasmus GBS Outcome Score, PE plasma exchange, SD standard deviation

*p < 0.05

aDelay between GBS onset and admission were available in 14/16 pGBS and 16/18 npGBS cases

bThese patients had at least 2 treatments: repeated IVIg infusions, combined IVIg and PE, or combined IVIg and CTX

cWithin 8 weeks after treatment

Obstetric characteristics of 16 pregnant women with GBS

Obstetric characteristics of this group of 16 pregnant women with GBS are detailed in Table 2. Fetal development was normal in 14 cases (87%), and 2 fetuses died in utero during the 3rd trimester. Ten patients (62%) had vaginal delivery, and six patients (37%) had cesarean section. Five caesarean sections were unscheduled, including emergency section in the two cases where in utero fetal death occurred. When considering post-partum, nine patients (56%) had a normal postpartum, two had postpartum hemorrhage, and one developed Sheehan syndrome. APGAR score and long-term psychomotor development were available for 10/14 children: APGAR score was normal in all ten cases, nine children presented with normal long-term psychomotor development, and one presented with delayed psychomotor development at age 4 years.

Table 2.

Obstetrical and child data of a group of 16 pregnant women with GBS (pGBS)

| pGBS, n = 16 | |

|---|---|

| First trimester GBS | 5 (31%) |

| Second trimester GBS | 5 (31%) |

| Third trimester GBS | 6 (38%) |

| Normal term delivery | 14 (87%) |

| Prematurity | 0 |

| In utero fetal death | 2 (12%) |

| Epidural anesthesia | 8 (50%) |

| General anesthesia | 3 (19%) |

| Vaginal delivery | 10 (62%) |

| Unscheduled cesarean | 5 (31%)a |

| Scheduled cesarean | 1 (6%) |

| Normal post-partum | 9 (56%) |

| Post-partum hemorrhage | 2 (12%) |

| Post-partum GBS fluctuation | 2 (12%) |

| Sheehan syndrome | 1 (6%) |

| Mean APGAR Score at 5 min | 9.9b |

| Neonatal ICU admission | 0 |

| Normal child psychomotor development | 9 (90%)c |

| Delayed child psychomotor development | 1 (10%)c |

Data are n (%). Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding

GBS Guillain-Barré syndrome, ICU Intensive Care Unit

aUnscheduled cesareans include two dead fetus deliveries and three labor-related emergencies

b5 min-APGAR scores were available for 10 newborns: one had score of 9 and nine had score of 10

cChild psychomotor development was available in ten cases

Fetal deaths characteristics

One fetus died during the third trimester of pregnancy from a pathologically proven congenital CMV infection. The mother had presented with CMV infection and GBS 13 weeks before fetal death and was treated with IVIg 12 weeks before fetal death. One fetus died during the third trimester of pregnancy in a context of maternal Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, and Low Platelet count Syndrome (HELLP) syndrome which occurred 10 days after GBS onset and 3 days after IVIg treatment discontinuation.

EDX characteristics of 16 pregnant women with GBS

EDX characteristics of this group of 16 women with pGBS are detailed in Table 3 and Supplemental Tables. NCS demonstrated demyelinating features in nine cases (64%), axonal loss features in two cases (14%), both axonal loss and demyelinating features in two cases (14%), and normal NCS in one case. Mean delay between GBS onset and EDX studies was 13 days. EDX studies were not performed in two cases. When considering patients admitted in ICU, 5/9 (55%) presented with severe axonal loss. When considering patients who needed mechanical ventilation, 3/4 (75%) presented with severe axonal loss.

Table 3.

A comparison of the paraclinical characteristics of a group of 16 pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) and a control group of 18 non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS)

| pGBS, n = 16 | npGBS, n = 18 | |

|---|---|---|

| CSF increased protein contenta | 12 (80%) | 8 (50%) |

| Normal CSF analysisa | 3 (20%) | 8 (50%) |

| CMV infection | 5 (31%) | 2 (11%) |

| Parvovirus B19 infection | 1 (6%) | 0 |

| Campylobacter jejuni infection | 0 | 0 |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| EBV infection | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| Sars-Cov2 infection | 0 | 1 (6%) |

| Antiganglioside antibodies in serumb | 3 (30%) | 7 (50%) |

| Demyelinating NCSc | 9 (64%) | 15 (88%) |

| Axonal NCSc | 2 (14%) | 1 (6%) |

| Axonal and demyelinating NCSc | 2 (14%) | 0 |

| Normal NCSc | 1 (7%) | 1 (6%) |

| Mean delay between GBS onset and EDX (days) | 13 ± 6 | 10 ± 7 |

Data are given as n (%) and means ± SD. Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding

CMV cytomegalovirus, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, EBV Epstein-Barr virus, EDX electrodiagnostic studies, GBS Guillain-Barré syndrome, NCS nerve conduction studies, Sars-Cov2 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

aCSF analysis was performed in 15/16 pGBS and 16/18 npGBS cases

bAntiganglioside antibodies were investigated in 10/16 pGBS and 14/18 npGBS cases

cEDX studies were not performed in 2/16 pGBS and 1/18 npGBS cases. Initial EDX studies were normal in two cases, and demyelinating abnormalities appeared on follow-up

Paraclinical characteristics of 16 pregnant women with GBS

Paraclinical characteristics of this group of 16 women with pGBS are detailed in Table 3. CSF analysis revealed increased protein content in 12/15 patients (80%) and was normal in 3/15 patients (20%). Mean delay between GBS onset and CSF analysis was 9 days (1–19). Six women presented with biological evidence of recent infection, including CMV in five cases and parvovirus B19 in one case. When considering the five women with CMV infection, three presented with primary infection and two with viral reactivation.

Comparison of 16 pregnant women with GBS and 18 non-pregnant women with GBS

A comparison between the two groups is detailed in Tables 1 and 3. In comparison with the npGBS group, patients from the pGBS group more often presented with CMV-related GBS (31% vs 11%), prolonged delay between GBS onset and hospital admission (delay > 7 days: 57% vs 12%, p = 0.018), increased ICU admission (56% vs 33%), and increased mechanical ventilation (25% vs 11%). Patients in the pGBS group also presented with more severe mEGOS & EGRIS prognostic scores at admission (mEGOS score: 4.1 vs 1.1, p = 0.04; EGRIS score 2.7 vs 1.8), more frequent TRF (37% vs 0%, p = 0.006), and were more frequently treated with a second IVIg course (62% vs 11%, p = 0.003). Overall, pGBS was more severe than npGBS, although maternal neurological outcome was excellent in both groups.

Discussion

In this nationwide retrospective case–control study, we reported the clinical, paraclinical, and obstetrical data of pregnant women with GBS (pGBS) and compared them with a group of non-pregnant women with GBS (npGBS). Our study shows that pGBS is rare, more severe than npGBS, and presents with significant fetal mortality, i.e., 12.5% in our series.

Previous pGBS studies

Less than a hundred pregnant women with GBS have been described until now in the literature [2–5]. Studies published before the 1980s suggest that pGBS is more severe than npGBS and presents with significant maternal and fetal complications [5]. For instance, it has been reported that 34.5% of women with pGBS required ventilatory support and that maternal mortality exceeded 10% [5]. However, these cases were reported at a time when active treatments, i.e., IVIg and PE, and modern intensive care technics were not available. In contrast, more recent studies originating from India, China and Serbia suggest that pGBS has limited maternal and fetal complications [2–4]. However, the latter studies present with limited clinical and paraclinical data, and active treatments were not available in a majority of cases [2–4]. In contrast with the previous, our study analyzed women with pGBS in a University Hospital setting with active treatments and modern intensive care technics available in all cases. Interestingly, our study demonstrates that pGBS presents with significant maternal morbidity and fetal mortality. As our results originate from a developed western country with easy access to ICU, IVIg and PE, i.e., a best-case scenario, one may extrapolate pGBS is indeed a severe condition which needs wider recognition and should not be considered as a “common” GBS.

Clinical features of pGBS

Our study suggests pGBS is more severe than npGBS. Indeed, in our study, pGBS patients presented with more ICU admissions, mechanical ventilation and TRF than matched npGBS patients. What could be the explanation for such a difference? Interestingly, we observed the delay between GBS onset and hospital admission was longer in pGBS in comparison with npGBS, i.e., 9 days vs 6 days, and we wondered whether this increased delay might play a role in our findings. However, a recent retrospective study showed there was no correlation between GBS diagnostic delay and ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and inpatient mortality [11]. We also wondered whether pregnancy-related physiological changes might explain the difference between pGBS and npGBS. For instance, increased blood volume during pregnancy may lead to inappropriate IVIg dosage, and it is known that pregnancy may aggravate the course of autoimmune disorders, e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus [12]. Pregnancy-related changes in respiratory dynamic and respiratory exchanges, including hyperventilation, decreased expiratory reserve volume (ERV), decreased functional residual capacity (FRC), increased oxygen consumption, decreased oxygen reserve, decreased alveolar and arterial carbon dioxide tension (PCO2), and increased arterial oxygen tension (PAO2) may also have contributed to this difference between pGBS and npGBS [13]. We also wondered whether active treatments, i.e., IVIg and PE, were involved in this difference between pGBS and npGBS. Indeed, in contrast with PE, IVIg do not involve significant blood volume alterations and are usually considered safer for the fetus and a better choice for treating pGBS. However, as 93% of our pGBS cases and 94% of our npGBS cases were treated with IVIg, it seems unlikely treatment accounted for significant differences between pGBS and npGBS severity. Interestingly, despite different severity between pGBS and npGBS, long-term recovery was excellent in both groups. Eventually, the difference between pGBS and GBS may also be explained by CMV infection. Indeed, 31% of patients in the pGBS group had CMV infection, and it is established that CMV-related GBS is associated with more severe disease [14]. Our study shows the delay between GBS onset and hospital admission was longer in pGBS in comparison with npGBS, i.e., 9 days vs 6 days. When investigating the cause of such a difference, we found sensory symptoms in pregnant women were often underestimated and attributed to pregnancy-related conditions. For instance, several patients in our series presented with feet paresthesia that were mistakenly attributed to pregnancy-related distal lower limb edema, resulting in delayed GBS diagnosis.

The role of CMV in pGBS

Our study shows the major importance of CMV infection in pGBS. Indeed, we observed CMV-related GBS was more frequent in the pGBS group in comparison with the npGBS group, i.e., five cases in the pGBS group (31%) vs two cases in the npGBS group (11%). CMV infection is a well-known trigger for GBS, and a preceding CMV infection is observed in approximately 4% of GBS cases in the general population, consistent with the rate observed in our control group [15]. In one pGBS case in our series, CMV infection provoked fetal death. Congenital CMV is the most frequent infectious cause of fetal complications and newborn malformation in developed countries, including congenital CMV, fetal death, and newborn ear and brain abnormalities [10]. There is no validated treatment for pregnant women with CMV infection, although education and prevention strategies for mothers have been shown to be beneficial [10]. Considering the significant morbidity of CMV in our study, we recommend systematic testing for CMV infection in pregnant women with GBS.

Fetal death in pGBS

In our study, two pregnant women with GBS lost their child. One death was the direct result of CMV infection and the other occurred in the immediate aftermath of a HELLP Syndrome. In the first case, maternal primary CMV infection was diagnosed at the same time than GBS. Nine weeks later, ultrasound examination demonstrated severe fetal abnormalities consistent with congenital CMV, and fetal death was observed 4 weeks later. Placenta pathological analysis confirmed massive CMV infection. In the second case, the patient developed HELLP syndrome 10 days after GBS was diagnosed, and 3 days after IVIg treatment was interrupted. Fetal death occurred at the same time HELLP syndrome was diagnosed. HELLP syndrome is a multisystem disorder rarely observed during pregnancy, and it usually complicates gestational hypertensive disease, leading in some cases to stillbirth and neonatal death [16]. Importantly, in the case described here, the patient had a history of uncontrolled arterial hypertension which may be the cause of HELLP syndrome. Whether there is a link between GBS, IVIg treatment, HELLP syndrome and fetal death in the case reported here remains unclear.

Epidemiology of pGBS

A recent study showed there were approximately 118 GBS cases in females aged 20–40 years each year in France [17]. When considering there are 800.000 pregnant women in France every year, i.e., 2% of total French female population, one may speculate that 2% of the previous 118 female group may be pregnant, which means there may be approximately 2 pGBS each year in France [17, 18]. These results mean we should theoretically have identified approximatively 40 pGBS cases in France in the 2002–2022 period, which was not the case. Several factors may explain this result: first, as explained by the authors in the paper, the study by Delannoy et al. most probably overestimated GBS cases; second, the Delannoy et al. study investigated the 2008–2013 period, which not may be representative of the 2002–2022 period we analyzed; third, our data retrieval was retrospective, which means it is likely several cases were missed, most especially in small health care structures which were not included in our study [17].

Limitations of our study

Our study has limits. First, the retrospective design led to missing data, including detailed clinical and EDX follow-up. Furthermore, as not all University Hospitals had electronic files dating back to 2002, it is likely we missed some pGBS patients as the result of a recall bias. Second, the multicentric design led to absent standardized data collection and clinical evaluation. When considering EDX studies, the same variability was observed between each recruiting center. Third, one may wonder whether our results can be generalized. For instance, all GBS patients in our series presented with an excellent neurological recovery, in contrast with other GBS series showing roughly 20% of patients not able to walk unaided several months after GBS [1]. Our findings may simply be related to the fact that we investigated young patients with no major associated morbidities. Indeed, it is known that GBS recovery depends in part on age and related morbidities, with elderly patients being more at risk of delayed recuperation [1]. Illustrating this point, age is a major component of the mEGOS GBS outcome score [6]. We also observed in our series no preceding Campylobacter jejuni infection, in contrast with other GBS series consistently showing Campylobacter jejuni infection as the most frequent infection preceding GBS [1, 15]. Our findings may simply be related to the fact that we investigated young pregnant women from a western developed country, i.e., women with close medical and nutritional follow-up. Overall, our results may be generalizable to pGBS in developed western countries but probably not elsewhere. Fourth, one may wonder whether our control group is relevant. As our patients came from various hospitals at different times, we chose to recruit our controls in the same hospitals and timeframes to be sure both groups had similar diagnostic and treatment procedures and therefore avoid time- and location-related management discrepancies. We also matched both groups according to age to avoid potential age-related outcome discrepancies. However, we were not able to match patients for pre-existing risk factors such as arterial hypertension and CMV infection.

Conclusion

This retrospective nationwide case–control study shows GBS in pregnancy is rare and presents with significant maternal morbidity and fetal mortality. Interestingly, CMV infection is a frequent cause of pGBS and should be systematically investigated when pregnant women develop GBS.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Data availability

All data and related files from this study are available on request to qualified researchers with no time limit, and subject to a standard data-sharing agreement.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Our study was conducted retrospectively on documented patient records with no specific intervention of any kind, local ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

References

- 1.Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;388(10045):717–727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma SR, Sharma N, Masaraf H, Singh SA. Guillain-Barré syndrome complicating pregnancy and correlation with maternal and fetal outcome in North Eastern India: a retrospective study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18(2):215–218. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.150608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu YW, Lin J, Zhang LX, et al. Classification of pregnancy complicating Guillain-Barré syndrome. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;99(18):1401–1405. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.18.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ždraljević M, Radišić V, Perić S, Kačar A, Jovanović D, Berisavac I. Guillain-Barré syndrome during pregnancy: a case series. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022;48(2):477–482. doi: 10.1111/jog.15116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan LYS, Tsui MHY, Leung TN. Guillain-Barré syndrome in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(4):319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doets AY, Lingsma HF, Walgaard C, et al. Predicting outcome in Guillain-Barré syndrome: international validation of the modified Erasmus GBS outcome score. Neurology. 2022;98(5):e518–e532. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doets AY, Walgaard C, Lingsma HF, et al. International validation of the Erasmus Guillain-Barré syndrome respiratory insufficiency score. Ann Neurol. 2022;91(4):521–531. doi: 10.1002/ana.26312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walgaard C, Lingsma HF, Ruts L, van Doorn PA, Steyerberg EW, Jacobs BC. Early recognition of poor prognosis in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Neurology. 2011;76(11):968–975. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182104407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Gidudu J, et al. The Brighton Collaboration GBS Working Group. Guillain-Barré syndrome and Fisher syndrome: case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2011;29:599–612. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawlinson WD, Boppana SB, Fowler KB, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(6):e177–e188. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bose S, Loo LK, Rajabally YA. Causes and consequences of diagnostic delay in Guillain-Barré syndrome in a UK tertiary center. Muscle Nerve. 2022;65(5):547–552. doi: 10.1002/mus.27506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eudy AM, Siega-Riz AM, Engel SM, et al. Effect of pregnancy on disease flares in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):855–860. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LoMauro A, Aliverti A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy. Breathe. 2015;11:297–301. doi: 10.1183/20734735.008615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visser LH, van der Meché FG, Meulstee J, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection and Guillain-Barré syndrome: the clinical, electrophysiologic, and prognostic features. Neurology. 1996;47:668–673. doi: 10.1212/WNL.47.3.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonhard SE, van der Eijk AA, Andersen H, et al. An international perspective on preceding infections in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: the IGOS-1000 cohort. Neurology. 2022;99(12):e1299–e1313. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, de Groot CJM, Hofmeyr GJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):999–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delannoy A, Rudant J, Chaignot C, Bolgert F, Mikaeloff Y, Weill A. Guillain-Barré syndrome in France: a nationwide epidemiological analysis based on hospital discharge data (2008–2013) J Peripher Nerv Syst JPNS. 2017;22(1):51–58. doi: 10.1111/jns.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.INSEE (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). Demography report 2021. Accessed Aug 17, 2022. https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/6049017

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and related files from this study are available on request to qualified researchers with no time limit, and subject to a standard data-sharing agreement.

All data and related files from this study are available on request to qualified researchers with no time limit, and subject to a standard data-sharing agreement.