Summary

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a neurogenetic disorder due to loss-of-function TSC1 or TSC2 variants, characterized by tumors affecting multiple organs, including skin, brain, heart, lung, and kidney. Mosaicism for TSC1 or TSC2 variants occurs in 10%–15% of individuals diagnosed with TSC. Here, we report comprehensive characterization of TSC mosaicism by using massively parallel sequencing (MPS) of 330 TSC samples from a variety of tissues and fluids from a cohort of 95 individuals with mosaic TSC. TSC1 variants in individuals with mosaic TSC are much less common (9%) than in germline TSC overall (26%) (p < 0.0001). The mosaic variant allele frequency (VAF) is significantly higher in TSC1 than in TSC2, in both blood and saliva (median VAF: TSC1, 4.91%; TSC2, 1.93%; p = 0.036) and facial angiofibromas (median VAF: TSC1, 7.7%; TSC2 3.7%; p = 0.004), while the number of TSC clinical features in individuals with TSC1 and TSC2 mosaicism was similar. The distribution of mosaic variants across TSC1 and TSC2 is similar to that for pathogenic germline variants in general TSC. The systemic mosaic variant was not present in blood in 14 of 76 (18%) individuals with TSC, highlighting the value of analysis of multiple samples from each individual. A detailed comparison revealed that nearly all TSC clinical features are less common in individuals with mosaic versus germline TSC. A large number of previously unreported TSC1 and TSC2 variants, including intronic and large rearrangements (n = 11), were also identified.

Keywords: tuberous sclerosis complex, low-level mosaicism, TSC1, TSC2, massively parallel sequencing, variant detection, TSC angiofibroma, TSC angiomyolipoma

Graphical abstract

We characterize TSC1/TSC2 mosaicism, analyzing 330 samples from different tissues from 95 individuals with TSC. Mosaic variant allele frequency was significantly higher in TSC1 than in TSC2. The mosaic variant was not present in blood in 18% of individuals with TSC, highlighting the value of analyzing multiple tissue samples.

Main text

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) (MIM: 191100 and MIM: 613254) is a neurogenetic autosomal-dominant tumor-suppressor gene syndrome due to loss-of-function heterozygous or mosaic variants in either TSC1 (MIM: 605284) or TSC2 (MIM: 613254). It is characterized by multiple hallmark clinical features, including hamartomatous tumors affecting the skin (facial angiofibroma [FAF], ungual fibroma [UF], shagreen patch [SP]), brain (subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [SEGA]), heart (cardiac rhabdomyomas), lung (lymphangioleiomyomatosis [LAM]), and kidney (angiomyolipoma [AML]).1,2 TSC tumors follow the Knudson two-hit tumor-suppressor model3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 such that the germline genetic variant leading to inactivation of one allele of either TSC1 or TSC2 (“first hit”) is followed by a somatic “second hit” that inactivates the other allele of the same gene. Mosaicism for inactivating TSC1 or TSC2 variants affecting multiple tissues (which we call generalized or systemic mosaicism) is an important phenomenon in TSC,1,11 observed in 10%–15% of individuals with TSC, reported in 7.5%12 and 10%,13 respectively. In recent years, our group has published several studies characterizing low-level mosaicism in TSC.10,12,13,14,15,16

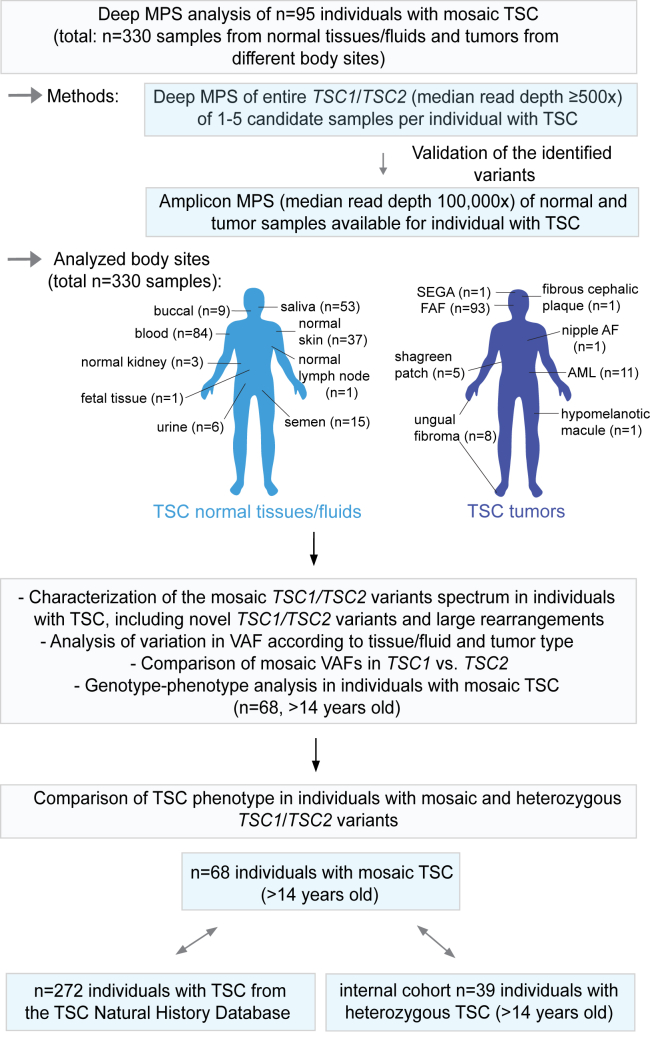

Herein, to further characterize mosaicism in TSC, we combined all of the individuals with mosaic TSC we have reported previously (from studies S1,12 S2,14 S3,15 S413) and an additional previously unreported set of 22 mosaic individuals (S5) and gathered comprehensive genotype and phenotype data for this combined cohort of individuals with mosaic TSC1 or TSC2 (n = 95) (Figure 1, Tables S1 and S2). These 22 newly reported mosaic individuals were identified from a set of 28 individuals with TSC with no mutation identified (NMI) by prior routine diagnostic genetic testing in certified clinical labs, in whom mosaic or heterozygous TSC1 or TSC2 variants were identified in 26 of 28 (93%).

Figure 1.

Flow-diagram outlining study design

The MPS methodology, analyzed tissue types, and subsequent steps of TSC genetic and genotype-phenotype analysis are shown. Abbreviations: AML, angiomyolipoma; FAF, facial angiofibroma; MPS, massively parallel sequencing; nipple AF, nipple angiofibroma; SEGA, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; VAF, variant allele frequency.

Deep massively parallel sequencing (MPS) (median read depth ≥ 500×) was performed in the 95 individuals with TSC as described previously, covering the entire genomic (exonic and intronic) extent of TSC1 and TSC2 in most samples,12,13,14,15 with analysis by our custom in-house computational pipeline, sensitive to allele frequencies < 1%.13,14 In this initial MPS analysis, 1–5 samples were analyzed per individual. Candidate mosaic variants identified in the MPS analysis were validated by either targeted amplicon MPS (S1,12 S2,14 S3,15 S413) or our multiplex high-sensitivity PCR amplification (MHPA) assay10 (S5) (median read depth 100,000×) (Figure 1). SNaPshot, Sanger sequencing, and PCR-based genotyping assays were also used for validation of some variants. These candidate mosaic variants were also assessed in other samples available for each individual with TSC. The identified variants were named according to GenBank: NM_000368.5 for TSC1 and according to GenBank: NM_000548.5 for TSC2. Additional details are available in the supplemental material and methods.10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22

A total of 330 samples from these 95 mosaic individuals were analyzed (range of the total number of samples analyzed in both initial MPS and validation analysis: 1–8 per individual, median: 4); the samples were derived from different TSC normal tissues/fluids and TSC tumors from different body sites (Figure 1, Table S1). Sequencing data for 222 samples from 73 mosaic individuals were available from our previous studies (S1–S412,13,14,15,16 [Table S1]), while data for the remaining 108 samples from 22 mosaic individuals were recently generated and not reported before (study S5 [Table S1]).

In addition, for the purpose of TSC mosaic versus heterozygous phenotype comparison, we have included 39 individuals with heterozygous TSC1 or TSC2 variants (six male and 33 female; age range: 15–64 years, median: 35) (from our studies reported previously, i.e., S1 and S312,15,23 and from S5). Information on n = 272 individuals with TSC available from the TSC Natural History Database (NHD) was also used (https://www.tscalliance.org/researchers/natural-history-database/) (Figure 1, Table S2). For this TSC mosaic versus heterozygous phenotype comparison, individuals with TSC were required to be >14 years old because TSC clinical features have variable age of onset and some are seen at relatively low frequency in younger individuals. For this phenotype comparison, we have included only individuals with identified systemic mosaic TSC1 or TSC2 variants. NHD individuals were matched 4:1 to the mosaic individuals (n = 68) by sex and age ±6 years and were derived from those who had molecular testing in clinical labs and had a definite TSC diagnosis. Individuals from NHD with unknown status for ≥5 out of 14 clinical features studied were not included in this comparison.

All individuals included in our study provided written informed consent or assent and parents’ consent. Individuals were enrolled under the research protocols approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs): the Human Research Committee of Mass General Brigham (1999P010781, 2013P002667, 2021P000046), NHLBI Protocols (00-H-0051, 95-H-0186, 96-H-0100, and/or 82-H-0032 [ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT00001975, NCT00001465, NCT00001532, and NCT00001183, respectively]), and local Ethics Committees at the clinical sites of EPISTOP trial.13 Demographic and clinical data were collected on the basis of medical records and self-reported questionnaire. All individuals had a full clinical examination by a health care provider familiar with TSC.

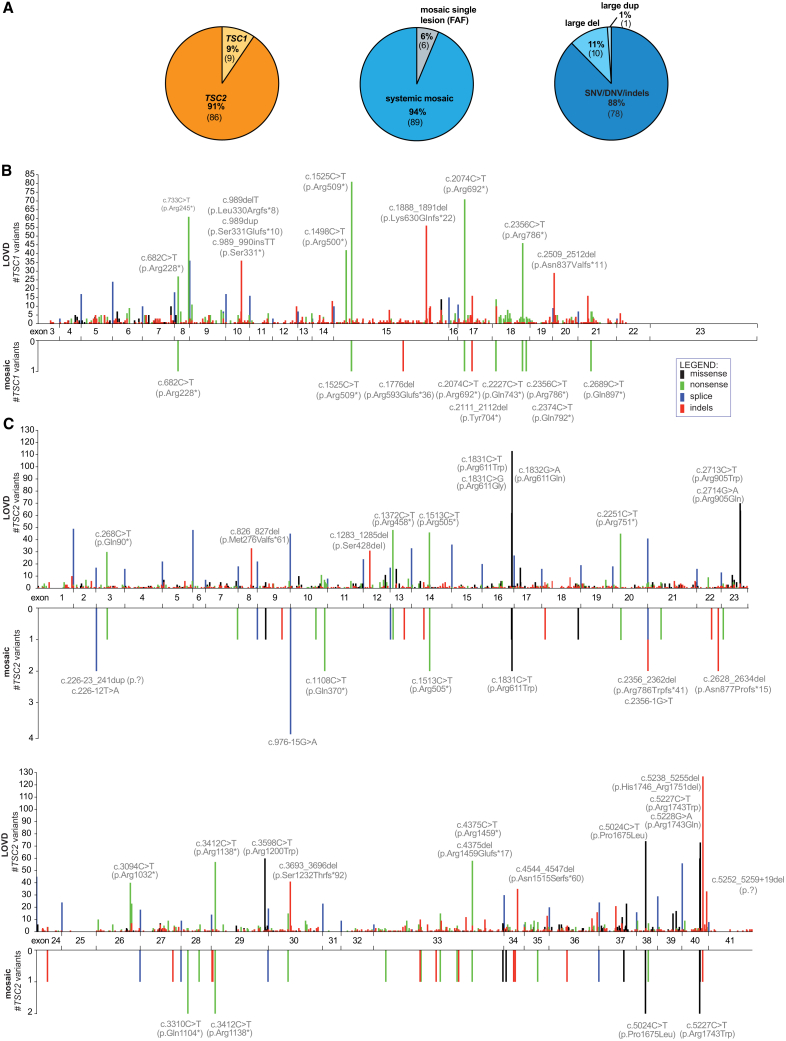

In total, 95 individuals meeting TSC diagnostic criteria were identified with mosaicism (n = 30 males, n = 64 females, and n = 1 fetus; age range: 0–70 years; median: 29.5) (Tables S1 and S2). Pathogenic TSC2 variants were identified in 86 (91%) individuals, while 9 (9%) had pathogenic TSC1 variants (Figure 2A), a distribution that is more skewed toward TSC2 variants than seen in general TSC (Leiden Open Variation Database [LOVD]1,22: 4,702 of 6,388 (74%) TSC2 versus 1,686 of 6,388 (26%) TSC1, p < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). 89 (94%) individuals had systemic (generalized) TSC1 or TSC2 mosaic variants, identified in blood and/or other fluids or tissues analyzed. The remaining six (6%) had TSC2 mosaic variants seen in a single FAF lesion but not detected in any other sample from the same individual. In these cases, the identified variant may be a somatic second-hit, with an unidentified first-hit variant occult to our detection methods. Alternatively, these six variants could be systemic mosaic variants, which were not seen in other samples (Figure 2A). 78 of 89 (88%) systemic mosaic variants were small variants (single-nucleotide variant [SNV], dinucleotide variant [DNV], or insertion/deletion [indels]), ten (11%) were large deletions, and one (1%) was a large duplication (Figure 2A, Table S1). Among 78 small systemic mosaic variants, there were 16 (21%) frameshift deletions, four (5%) frameshift duplications/insertions, one (1%) inframe deletion, 12 (15%) missense variants, 32 (41%) nonsense variants, and 13 (17%) splice variants (Table S1). There were 24 FAFs and two UFs from 21 individuals that had a systemic mosaic variant and one or more additional TSC1 or TSC2 variants (range: 1–3 variants) specific to a single cutaneous lesion consistent with somatic second-hit events. (Table S1). Four AMLs from two individuals had copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (Table S1), a common second hit mechanism in TSC AML as we have reported previously.4

Figure 2.

Spectrum of TSC1 and TSC2 variants identified in individuals with mosaic TSC

(A) Summary of the proportions of the identified TSC1 and TSC2 variants, extent of mosaicism (systemic versus restricted to single lesion), and different systemic mosaic variant types.

(B and C) Maps of the systemic mosaic variants in TSC1 (B) and TSC2 (C) (lower plots) compared with the mirror images of the maps of deleterious germline variants reported in LOVD (upper plots).1 The y axis indicates the number of TSC2 variants at a single nucleotide position. Each variant is represented by a vertical line with height proportional to the number of times it was seen. The color of the line indicates the type of variant, as shown in the inset legend. Hotspot variants are labeled with coding sequence nucleotide (c.) and amino acid (p.) position. Splice mutations are summed and shown as a single bar at each exon-exon junction. Abbreviations: SNV, single-nucleotide variant; DNV, dinucleotide variant; indels, small insertions/deletions; large del, large deletions; large dup, large duplications; LOVD, Leiden Open Variation Database.

The distribution of mosaic variants in TSC1 and TSC2 was similar to that seen for pathogenic germline mutations in general for TSC (LOVD22). Four of nine (44%) TSC1 and 25 of 69 (36%) TSC2 systemic mosaic small variants were located at known relative mutation hotspots, reported at least 20 times in LOVD22 (Figures 2B and 2C). The intronic TSC2 variant c.976−15G>A, a G>A transition at a CpG site known to affect splicing,12 was the most common mosaic mutation identified, seen in four of 95 (4%) mosaic individuals (Figure 2C).

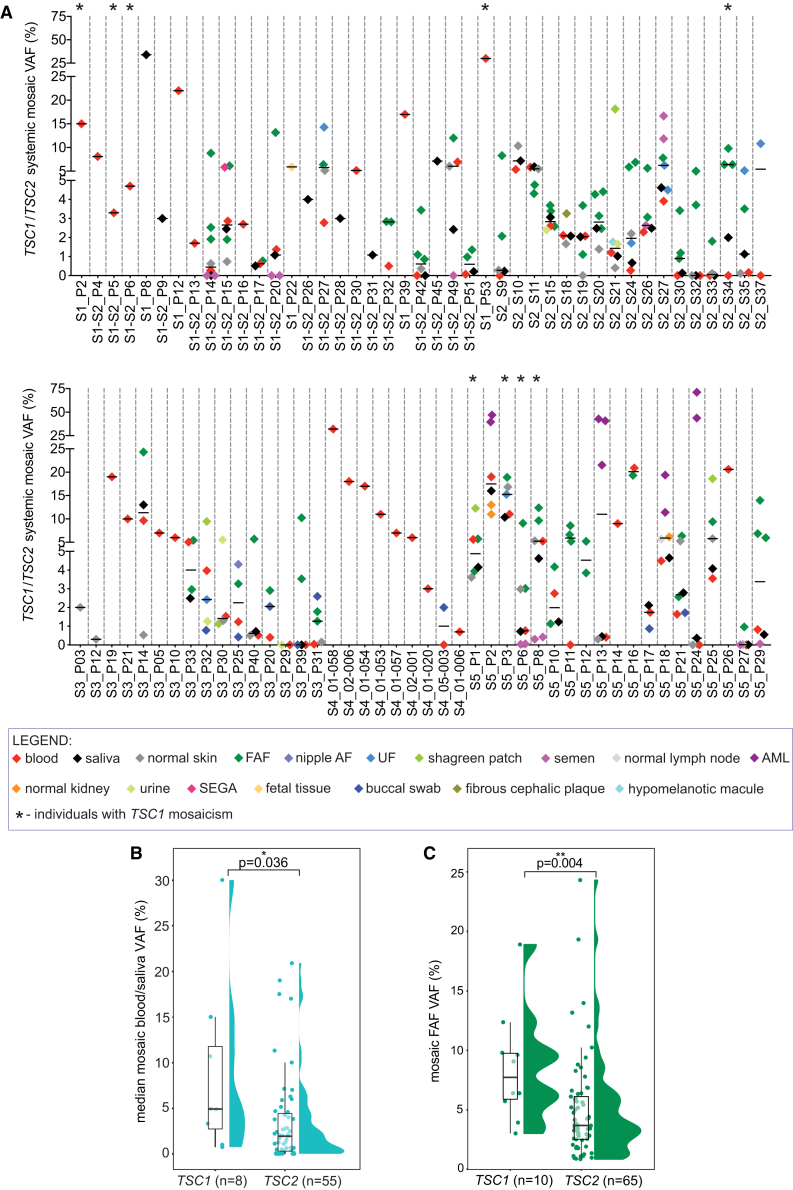

Analysis of multiple samples from the same individual in this large cohort of individuals with mosaic TSC enabled comparison of mosaic VAFs in samples from different TSC fluids, tissues, and tumor biopsies (Figures 3A and S1A). VAFs did not differ comparing blood and other normal body sites, such as saliva (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, p = 0.70), semen (p = 0.24), urine (p = 0.88), buccal swab (p = 0.74), or normal skin (p = 0.54) (Figures 3A and S1A). There was a strong correlation between VAFs in blood and saliva (r = 0.94, p < 0.0001, Figure S1B), suggesting that saliva can be used as a non-invasive alternative to blood for TSC genetic testing. VAFs were significantly higher in FAF compared to both matched normal skin and blood (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, both p < 0.0001) and in AML tumors in relation to matched normal kidney (p = 0.03). There was also a trend toward higher VAF for UF and SP compared to both matched normal skin and blood (compared to normal skin: p = 0.63 and p = 0.25, respectively; compared to blood: p = 0.04 and p = 0.13, respectively) (Figure S1A). The median systemic mosaic VAF in blood samples was very low, 2.73%, which is well below the level of detection/reporting of mosaic variants by most clinical testing labs. Furthermore, the systemic mosaic variant was not present in blood in 14 of 76 (18%) individuals, highlighting the value of analysis of multiple tumor and other samples from each individual (Figure S2). Notably, the median mosaic VAF in blood and/or saliva was significantly lower for TSC2 (median VAF = 1.93%) than for TSC1 (median VAF = 4.91%, Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.036) (Figure 3B) as well as for FAF (TSC2 median VAF = 3.69% versus TSC1 median VAF = 7.74%; Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.004) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Variation in VAF in different samples from individuals with mosaic TSC

(A) A summary plot of systemic mosaic TSC1 or TSC2 VAFs (y axis) in different matched TSC lesions and normal tissues/fluids, color-coded as indicated in the legend below. Individuals with TSC1 mosaicism are marked with asterisk, as indicated in the legend. This summary includes data for n = 87 individuals from whom the VAF of the identified variants was defined with MPS and for S5_P2 partially with Sanger sequencing. Summary data for each individual is separated with a dashed gray line, with individuals’ labels indicated below x axis. The horizontal black bold lines indicate median VAFs across samples analyzed for each of the individuals.

(B) Comparison of VAFs in blood/saliva in individuals with TSC1 and TSC2 mosaicism (median VAF in matched blood and saliva, or in either blood or saliva only if only one of these two samples was available for a given individual). The comparison was performed for TSC samples from individuals of age > 14. The p value was obtained via Mann-Whitney test.

(C) Comparison of VAFs in FAF biopsies from individuals with TSC1 and TSC2 mosaicism. The comparison was performed for TSC samples from individuals of age > 14. Each dot corresponds to a different FAF biopsy, and some individuals had two or more. The p value was obtained via Mann-Whitney test. VAF, variant allele frequency; FAF, angiofibroma; nipple AF, nipple angiofibroma; UF, ungual fibroma; AML, angiomyolipoma; SEGA, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma.

Remarkably, there was a significant positive correlation between the total number of TSC-related clinical features and median TSC1 VAF (r = 0.76, p = 0.03) and TSC2 VAF (r = 0.45, p = 0.0006) in blood and/or saliva (Figure 4). No significant difference was observed between the total or organ-specific (skin, brain, or kidney/lung [LAM]-related) number of TSC clinical features among individuals with TSC1 versus TSC2 mosaicism (Figure S3, Table S2).

Figure 4.

Correlation between TSC1 or TSC2 VAFs in blood/saliva and number of TSC clinical features

The analysis was performed for individuals with TSC of age > 14, with median VAF in matched blood and saliva or in either blood or saliva only if only one of these two samples was available. Each dot represents a distinct individual, with blue filled circles for those with a TSC1 variant and open circles for those with a TSC2 variant, as indicated in the legend. R represents Pearson’s correlation coefficient; R values are presented with the associated p values. The curves were generated via linear regression.

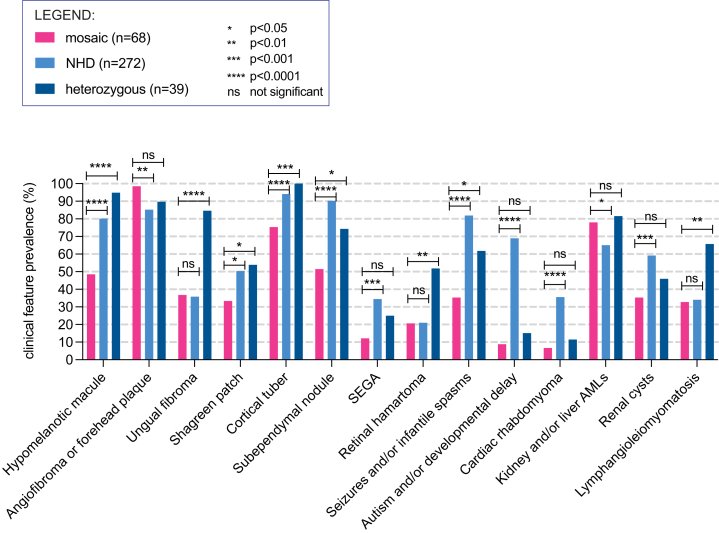

We also compared the prevalence of 14 hallmark TSC clinical features in 68 individuals with TSC with TSC1 or TSC2 mosaicism (age > 14 years, range (median) = 15–70 (32.5) years) and (1) 39 individuals with TSC with heterozygous TSC1 or TSC2 variants identified in our studies (age > 14 years old, range (median) = 15–64 (35), from S1,12 S3,15 and S5) and (2) 272 individuals with TSC from the TSC Natural History Database (NHD) (age- and -sex matched with mosaic cohort, age > 14 years, range (median) = 15–74 (30) years) (Figures 5 and S4A). 12 of 14 (86%) TSC clinical features were significantly less common in the mosaic cohort in comparison to one or both of the heterozygous and NHD cohorts (Fisher’s exact test, p from <0.05 to <0.0001) (Figure 5). In contrast, FAF or fibrous cephalic plaque, a TSC skin lesion feature, was significantly more common in the mosaic cohort (67 of 68, 99%) than the NHD (231 of 271, 85%, p < 0.01) cohort. AMLs were also more frequent in mosaic individuals (53 of 68, 78%) than in NHD (177 of 272, 65%, p < 0.05) (Figure 5). As expected, the total number of TSC clinical features was significantly higher in either NHD (median n = 8) or heterozygous (median n = 8) cohorts in comparison to the mosaic cohort (median n = 5) (Mann-Whitney, p < 0.0001 for both comparisons), although there was a wide distribution for all three cohorts (Figure S4B).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the prevalence of 14 TSC hallmark clinical features in mosaic TSC versus heterozygous TSC

68 individuals with systemic TSC1 or TSC2 mosaic variants age > 14 years were compared to a TSC cohort from the TSC Natural History Database (NHD, n = 272) and an internal cohort with heterozygous TSC1 or TSC2 variants (n = 39). p values are indicated for pairwise comparisons of the cohort of individuals with mosaic TSC with each of the other two cohorts, with Fisher’s exact test.

11 variants not reported in LOVD were identified in the 28 individuals with NMI from cohort S5 (Table S1). These included (1) a TSC2 39 bp duplication encompassing an acceptor splice site at intron 3/exon 4 (c.226−23_241dup); (2) three TSC2 large deletions (including a mosaic germline deletion of most of TSC2 exon 39 [167 bp], a de novo heterozygous germline deletion of NTHL1 exon 1 – TSC2 exon 15 (18 kb), and a mosaic germline deletion of TSC2 exon 26 – exon 39 [11 kb]); (3) a large duplication of TSC2 exon 4 – exon 16 (19 kb); (4) a large TSC1 intronic insertion (c.2392−149_2392-148insN[?]); (5) a de novo (not seen in parents) heterozygous TSC1 intronic single-nucleotide deletion (c.363+749del) with predicted effect on TSC1 splicing (in silico Human Splicing Finder24); and (6) a large inversion of TSC2 exon31 – ABCA3 exon13 (221 kb) identified in the amniotic fluid sample (see Table S1 for details). Interestingly, the UF from the individual with the TSC1 large intronic insertion (c.2392−149_2392-148insN[?]) showed TSC1 copy-neutral LOH, which has not been previously reported as a second-hit mechanism in TSC cutaneous lesions.

This study provides comprehensive information on a very large cohort of individuals with TSC1 and TSC2 mosaicism, n = 95. We analyzed a total of 330 samples derived from individuals with TSC, enabling comprehensive characterization of the spectrum of TSC mosaic variants, definition of the ranges of mosaic VAFs in various TSC tissues and bodily fluids, comparison of TSC1 and TSC2 mosaicism, and genotype-phenotype correlations.

Our analyses of mosaicism (S1–S512,13,14,15), including the present additional 22 individuals, have consistently shown a higher rate of mosaicism in TSC compared to many other tumor-suppressor syndromes, for instance Li-Fraumeni syndrome.11 This is most likely due to the fact that clinical recognition and definite diagnosis is easier in syndromes with multiple distinctive clinical features, such as TSC, in which individuals usually have many lesions, especially FAF. Mosaicism in many tumor-suppressor syndromes is not well documented and most likely underestimated because of limited analysis of multiple tissue samples and methodological limitations.11 Our study design, including sampling of multiple tissues including tumor lesions (both FAF and others), contributed to our high success rate in mosaicism identification.

Furthermore, we routinely detected low-level mosaicism in TSC, with median blood DNA VAF of 2.7%. Notably, most commercial diagnostic laboratories have a current cut-off of 2%–10% VAF. Thus, many individuals with mosaic TSC gene mutations are not identified by such labs. Adoption of more sensitive methods for both sequencing (average depth of coverage of at least 500×) and computational analysis is warranted to permit detection of low-level mosaicism in TSC, as well as other mosaic genetic conditions, in clinically certified labs.11,25 In this same vein, we have recently developed MHPA,10 an ultra-sensitive amplification strategy including barcoding of single DNA molecules that enables error suppression and variant detection at VAF < 0.1%. The MHPA strategy has been adjusted and successfully applied for validation of mosaic variants in cohort S5 in the present study.

Our results suggest that in general higher levels of mosaicism are needed for TSC1 variants than TSC2 variants for diagnostic clinical symptoms to appear. Two observations fit this phenotypic difference: first, TSC1 mosaicism was much less common (9%) than TSC2 mosaicism (91%), in contrast to general TSC for which 26% of occurrences are due to TSC1 mutations, and second, VAFs were significantly higher for TSC1 mosaicism than for TSC2 mosaicism, for both blood/saliva and FAF samples. These findings are consistent with the observation in germline disease that TSC due to TSC1 variants is on average milder than TSC due to TSC2 variants.1 It appears that many individuals with low-level TSC1 mosaicism, VAF < 3% in blood/saliva, will not be diagnosed as having insufficient TSC clinical features to meet diagnostic criteria.

Comparison of TSC1 or TSC2 VAFs in matched samples from individuals with TSC showed no major difference among blood, saliva, semen, urine, and buccal swab. Both saliva and buccal swab samples consist of a mix of leukocytes and epithelial cells in a range of proportions, with a higher fraction of epithelial cells in buccal swabs in general and a higher fraction of leukocytes in saliva samples in general.26 Thus, saliva can be considered equivalent to blood for genetic testing applications, especially in adults.26,27,28 Our results support this equivalence, with a strong VAF correlation in matched blood and saliva samples. In contrast VAFs were higher in FAF, UF, and SP (median VAF of 4.27%, 9.70%, and 15.21%, respectively) samples in comparison to matched normal skin (median VAF = 0.74%, Figure S1A). Similarly, VAFs in AML (median 39.6%) were higher than those seen in normal kidney (median 11.0%) (Figure S1A). Since hamartomatous tumors that develop in TSC must have some enrichment for the germline mosaic allele, this makes sense and further supports the diagnostic strategy of analyzing pre-existing tumor samples when available. If such samples are not available, FAF biopsies are relatively safe and efficient, making these an ideal choice for biopsy and genetic analysis in our opinion. When FAF are not present or have been previously treated, then other TSC tumors, including ungual fibromas or shagreen patch, may serve as an alternative source of DNA for analysis.

Interestingly, our new cohort S5 had a high frequency of large rearrangements, including deletions, duplications, and inversions affecting TSC2, which are rare in TSC overall, accounting for ∼6% of all TSC2 variants (LOVD1,22). Detection of these rare pathogenic variants, previously missed in certified clinical labs, was possible because of our comprehensive sequencing of the entire genomic extent of TSC1/TSC2 and customized in-house computational analysis.

Notably, we observed a significant correlation between the number of TSC clinical features and median TSC1 or TSC2 VAF in blood and/or saliva, as observed before in a smaller number of TSC mosaic individuals in S214 and S3.15 Our study extends this observation with comparison of the correlation for TSC1 (r = 0.76, p = 0.03) and TSC2 (r = 0.45, p = 0.0006) individually. A higher fraction of cells with the mosaic variant usually reflects an earlier postzygotic event, resulting in a larger number of cells that are susceptible to a second hit event and tumor development.

Although there is no doubt that clinical manifestations for TSC individuals with mosaicism are less severe and less common in general than those seen in heterozygous individuals, some of the specific differences we observed were very likely due to the ascertainment methods employed in these studies. Many of the individuals studied here sought TSC genetic analysis because they were of reproductive age and had normal cognitive ability, prior TSC genetic testing had failed to identify a variant, and they wanted guidance as to risk of TSC transmission to offspring. Nonetheless they met standard TSC diagnostic criteria,29 of which FAF, cortical tubers, and AMLs and/or renal cysts were most common (Figure 5). These circumstances may explain in part why FAFs were seen in 99% of the mosaic individuals analyzed who were >14 years old.

Our cohort also had fairly pronounced skewing of the sex ratio in both our mosaic individuals and our heterozygous individuals: mosaic females versus males, 64 versus 30, binomial distribution test p = 0.0004; heterozygous females versus males, 33 versus 6, binomial distribution test p < 0.0001. This was particularly striking in the S3 group (females versus males, 27 versus 2), which came from the NIH LAM clinical program. This skewing toward female sex was most likely due at least in part to two factors. (1) Many of the mosaic individuals in our studies were of reproductive age and interested in genetic testing to make an informed decision about family planning. Females may be more interested in this topic than males. (2) Many of our subjects, especially the heterozygotes, were from the NIH LAM clinical program (including the S3 heterozygous group), which is enriched in women because of the pronounced female sex bias in the occurrence of LAM. This effect is also seen in the high frequency of LAM (66%) in the heterozygous cohort15 (Figure 5). Another limitation of our analysis is that NHD clinical data were collected on the basis of self-reported questionnaires and therefore may be inaccurate.

We suggest that other cohorts of individuals with mosaic TSC that are studied may not fit this same pattern of clinical features. In addition, they may not be so enriched for the low-level mosaicism seen here, which may be due to enrichment for individuals without autism, developmental delay, or seizures seeking genetic testing for family planning in our study. Nonetheless, larger numbers of individuals with TSC with very low-level mosaicism are expected due to the larger number of early embryonic cells at risk for TSC gene mutation as development proceeds, as noted previously.14

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Engles Family Fund for Research in TSC and LAM and FY2020 TSC Alliance Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (to K.K.), and the NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01HL131022-04 to T.N.D., D.J.K., and J.M.). K.G. was supported by the Department of Defense- W81XWH-17-380 1-0205 and Special Grant and Support Program for the Scholars’ Association Members of the Onassis Foundation. A.A. and A.M.T. were supported by the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the American Association for Dental Research, the Colgate-Palmolive Company, Genentech, and other private donors. In addition, A.M.T. was supported in part by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Research Mentorship grant #2018042. J.M. was supported by the intramural research program NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. We thank the TSC Alliance and contributors to the TSC Natural History Database. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the TSC Alliance. We thank all the individuals with TSC for their participation in this study and Krzysztof Sadowski, Paolo Curatolo, and Pavel Krsek for recruitment of individuals with TSC and clinical care in the EPISTOP study. The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense.

Author contributions

K. Klonowska conceptualized the study; collected TSC samples; performed DNA extraction and generated hybrid-capture MPS data for cohort S5; generated validation sequencing MHPA libraries and MPS data with QC; performed computational analyses and interpreted the MPS data; compiled and summarized genetic, clinical, and demographic data; performed all statistical analyses; wrote the manuscript; prepared all figures, tables, and supplementary materials; and acquired funding for the study. K.G. collected TSC samples; performed DNA extraction; and generated and provided hybrid-capture and amplicon MPS data results from individuals from cohort S2. J.M.G. collected and characterized skin biopsy samples and performed clinical examination of individuals with TSC. B.B. generated and provided MPS data results from individuals from cohort S4. A.R.T. contributed to generation and analysis of hybrid-capture and amplicon MPS data. Z.T.H. contributed to generation and preprocessing of the MHPA data. A.A. compiled and provided clinical and demographic data for cohort S3. A.M.T. compiled and provided clinical and demographic data for cohort S3. L.H. provided MPS data results from individuals with TSC from cohort S3. K. Kotulska and S.J. participated in clinical characterization of individuals with TSC from cohort S4. J.M. supported clinical evaluation and individuals with TSC from cohort S3. T.N.D. collected skin samples and characterized clinical results for individuals with TSC from cohort S3. D.J.K. conceptualized and supervised the study; recruited individuals with TSC from S1, S2, and S5; collected and reviewed clinical and demographic data; reviewed the MPS data; reviewed and participated in manuscript preparation together with K. Klonowska; and acquired funding for the study. All authors read and commented on the paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: May 3, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.04.002.

Contributor Information

Katarzyna Klonowska, Email: kklonowska@bwh.harvard.edu.

David J. Kwiatkowski, Email: dk@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

Web resources

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

The sequencing data and computational code from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Salussolia C.L., Klonowska K., Kwiatkowski D.J., Sahin M. Genetic etiologies, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2019;20:217–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083118-015354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curatolo P., Specchio N., Aronica E. Advances in the genetics and neuropathology of tuberous sclerosis complex: edging closer to targeted therapy. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:843–856. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knudson A.G., Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giannikou K., Malinowska I.A., Pugh T.J., Yan R., Tseng Y.Y., Oh C., Kim J., Tyburczy M.E., Chekaluk Y., Liu Y., et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies TSC1/TSC2 biallelic loss as the primary and sufficient driver event for renal angiomyolipoma development. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannikou K., Zhu Z., Kim J., Winden K.D., Tyburczy M.E., Marron D., Parker J.S., Hebert Z., Bongaarts A., Taing L., et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas are characterized by mTORC1 hyperactivation, a very low somatic mutation rate, and a unique gene expression profile. Mod. Pathol. 2021;34:264–279. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00659-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henske E.P., Neumann H.P., Scheithauer B.W., Herbst E.W., Short M.P., Kwiatkowski D.J. Loss of heterozygosity in the tuberous sclerosis (TSC2) region of chromosome band 16p13 occurs in sporadic as well as TSC-associated renal angiomyolipomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;13:295–298. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870130411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henske E.P., Scheithauer B.W., Short M.P., Wollmann R., Nahmias J., Hornigold N., van Slegtenhorst M., Welsh C.T., Kwiatkowski D.J. Allelic loss is frequent in tuberous sclerosis kidney lesions but rare in brain lesions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;59:400–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henske E.P., Wessner L.L., Golden J., Scheithauer B.W., Vortmeyer A.O., Zhuang Z., Klein-Szanto A.J., Kwiatkowski D.J., Yeung R.S. Loss of tuberin in both subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and angiomyolipomas supports a two-hit model for the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151:1639–1647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niida Y., Stemmer-Rachamimov A.O., Logrip M., Tapon D., Perez R., Kwiatkowski D.J., Sims K., MacCollin M., Louis D.N., Ramesh V. Survey of somatic mutations in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) hamartomas suggests different genetic mechanisms for pathogenesis of TSC lesions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:493–503. doi: 10.1086/321972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klonowska K., Grevelink J.M., Giannikou K., Ogorek B.A., Herbert Z.T., Thorner A.R., Darling T.N., Moss J., Kwiatkowski D.J. Ultrasensitive profiling of UV-induced mutations identifies thousands of subclinical facial tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Clin. Invest. 2022;132:e155858. doi: 10.1172/JCI155858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J.L., Miller D.T., Schmidt L.S., Malkin D., Korf B.R., Eng C., Kwiatkowski D.J., Giannikou K. Mosaicism in tumor suppressor gene syndromes: prevalence, diagnostic strategies, and transmission risk. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2022;23:331–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-120121-105450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyburczy M.E., Dies K.A., Glass J., Camposano S., Chekaluk Y., Thorner A.R., Lin L., Krueger D., Franz D.N., Thiele E.A., et al. Mosaic and intronic mutations in TSC1/TSC2 explain the majority of TSC patients with no mutation identified by conventional testing. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogórek B., Hamieh L., Hulshof H.M., Lasseter K., Klonowska K., Kuijf H., Moavero R., Hertzberg C., Weschke B., Riney K., et al. TSC2 pathogenic variants are predictive of severe clinical manifestations in TSC infants: results of the EPISTOP study. Genet. Med. 2020;22:1489–1497. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannikou K., Lasseter K.D., Grevelink J.M., Tyburczy M.E., Dies K.A., Zhu Z., Hamieh L., Wollison B.M., Thorner A.R., Ruoss S.J., et al. Low-level mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex: prevalence, clinical features, and risk of disease transmission. Genet. Med. 2019;21:2639–2643. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treichel A.M., Hamieh L., Nathan N.R., Tyburczy M.E., Wang J.A., Oyerinde O., Raiciulescu S., Julien-Williams P., Jones A.M., Gopalakrishnan V., et al. Phenotypic distinctions between mosaic forms of tuberous sclerosis complex. Genet. Med. 2019;21:2594–2604. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0520-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyburczy M.E., Wang J.A., Li S., Thangapazham R., Chekaluk Y., Moss J., Kwiatkowski D.J., Darling T.N. Sun exposure causes somatic second-hit mutations and angiofibroma development in tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:2023–2029. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alföldi J., Wang Q., Collins R.L., Laricchia K.M., Ganna A., Birnbaum D.P., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., Brown G.R., Chao C., Chitipiralla S., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., Mesirov J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vis J.K., Vermaat M., Taschner P.E.M., Kok J.N., Laros J.F.J. An efficient algorithm for the extraction of HGVS variant descriptions from sequences. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3751–3757. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fokkema I.F.A.C., Taschner P.E.M., Schaafsma G.C.P., Celli J., Laros J.F.J., den Dunnen J.T. LOVD v.2.0: the next generation in gene variant databases. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:557–563. doi: 10.1002/humu.21438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathan N., Tyburczy M.E., Hamieh L., Wang J.A., Brown G.T., Richard Lee C.C., Kwiatkowski D.J., Moss J., Darling T.N. Nipple angiofibromas with loss of TSC2 are associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2016;136:535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desmet F.O., Hamroun D., Lalande M., Collod-Béroud G., Claustres M., Béroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Z., Lin S., Zhao X., Bennett M.F., Brown N.J., Wallis M., Gao X., Sun L., Wu J., Vedururu R., et al. Mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex: Lowering the threshold for clinical reporting. Hum. Mutat. 2022;43:1956–1969. doi: 10.1002/humu.24454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theda C., Hwang S.H., Czajko A., Loke Y.J., Leong P., Craig J.M. Quantitation of the cellular content of saliva and buccal swab samples. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:6944. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham J.E., Maranian M.J., Spiteri I., Russell R., Ingle S., Luccarini C., Earl H.M., Pharoah P.P.D., Dunning A.M., Caldas C. Saliva samples are a viable alternative to blood samples as a source of DNA for high throughput genotyping. BMC Med. Genomics. 2012;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meghnani V., Mohammed N., Giauque C., Nahire R., David T. Performance characterization and validation of saliva as an alternative specimen source for detecting hereditary breast cancer mutations by next generation sequencing. Int. J. Genomics. 2016;2016:2059041. doi: 10.1155/2016/2059041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Northrup H., Aronow M.E., Bebin E.M., Bissler J., Darling T.N., de Vries P.J., Frost M.D., Fuchs Z., Gosnell E.S., Gupta N., et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021;123:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data and computational code from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.