Abstract

Histological and lineage immunofluorescence examination revealed that healthy conducting airways of humans and animals harbor sporadic poorly differentiated epithelial patches mostly in the dorsal noncartilage regions that remarkably manifest squamous differentiation. In vitro analysis demonstrated that this squamous phenotype is not due to intrinsic functional change in underlying airway basal cells. Rather, it is a reversible physiological response to persistent Wnt signaling stimulation during de novo differentiation. Squamous epithelial cells have elevated gene signatures of glucose uptake and cellular glycolysis. Inhibition of glycolysis or a decrease in glucose availability suppresses Wnt-induced squamous epithelial differentiation. Compared with pseudostratified airway epithelial cells, a cascade of mucosal protective functions is impaired in squamous epithelial cells, featuring increased epithelial permeability, spontaneous epithelial unjamming, and enhanced inflammatory responses. Our study raises the possibility that the squamous differentiation naturally occurring in healthy airways identified herein may represent “vulnerable spots” within the airway mucosa that are sensitive to damage and inflammation when confronted by infection or injury. Squamous metaplasia and hyperplasia are hallmarks of many airway diseases, thereby expanding these areas of vulnerability with potential pathological consequences. Thus, investigation of physiological and reversible squamous differentiation from healthy airway basal cells may provide critical knowledge to understand pathogenic squamous remodeling, which is often nonreversible, progressive, and hyperinflammatory.

Keywords: WNT signaling, human airway epithelium, squamous differentiation, glycolysis, innate immunity

Three principal cell epithelial cells have been described: squamous epithelium, cuboidal epithelium, and columnar epithelium. They cover internal and external surfaces of epithelial organs and perform foundational physiological functions such as protection, secretion, and absorption. Squamous epithelial cells, defined by two or more layers of cells and the presence of intercellular bridges or keratinization, represent a stratified mucosal epithelial cell surface phenotype found in the skin and esophagus. The respiratory tree, from the nasal cavity to the small bronchi, is lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium comprising basal cells that function as stem cell reservoirs to regenerate the differentiated luminal populations, such as ciliated cells and mucosecretory cells. Together they protect the airways from infections and inhaled gases and particles by providing mucociliary clearance and innate immune responses (1, 2). Despite being classified as pseudostratified, transcriptomic analysis at single-cell resolution has identified fractions of the human airway and nasal epithelial cells expressing squamous cell markers such as KRT13 (keratin 13) in in vitro culture (3, 4) and within the homeostatic nasopharynx and tracheobronchial tissues (5–7). Similar KRT13-expressing clusters were also reported in wild-type mouse trachea, named “hillock” cells (8). How basal stem cells of pseudostratified tissues decide to adopt squamous cell fate has not been well elucidated. This process likely requires the coordinated activation of genes specific to squamous differentiation and the repression of genes specific to mucociliary differentiation.

The tracheobronchial tree of humans and animals is a cartilage tissue that can stretch during respiration. It consists of C-shaped cartilaginous rings that cover the ventral region and is closed by fibroelastic and smooth muscle tissue in the dorsal parts. Smooth muscle tissue can be also found in tracheal ligaments between the adjacent rings. Longitudinally, the trachea is bifurcated into two main bronchi, which are functionally divided into various generations of conducting airways and respiratory zones, allowing air to be inhaled into the lungs for respiration. It is reasonable to speculate that this architectural or anatomic variation could directly or indirectly influence epithelial cell differentiation and physiological functions. Indeed, it has been well recognized for centuries by simple histological examination that airway epithelial cells along the proximal–distal axis differ in thickness and cellular composition. Recent molecular lung atlas data further confirmed that proximal and distal regions of human and mouse healthy airways have distinct cell subtypes and transcriptomic signatures. These are under the control of distinct cellular and regulatory signaling networks that show different sensitivity in response to stimulation, perform distinct physiological functions, and play different reparative roles in tissue homeostasis and regeneration (7–9). The varying cellular composition and functions of airway epithelial cells along the ventral and dorsal horizontal axis are less studied but recognized. For example, substantial heterogeneity in rates and directions of mucociliary transport has been noted in the ventral and dorsal pig trachea (10). Whole-mount staining on mouse trachea indicates that fewer ciliated cells are presented in dorsal regions, whereas ventral regions are fully covered by ciliated epithelial cells (11). Intriguingly, KRT13+ hillock cells are also identified mainly in dorsal regions and intercartilaginous rings (8), overlapping with areas with the loss of ciliated epithelial cells (11). Lineage tracing using Krt5-CreER showed that basal cells of the dorsal trachea are enriched with squamous gene expressions such as KRT6a and KRT13 (11). Whether these “keratinized” basal cells and hillock cells represent the same cell population is unclear and requires further characterization. Currently, the study of epithelial cell heterogeneity in human airways along the dorsal–ventral axis is lacking. Furthermore, the physiological relevance of human epithelial subpopulations is unclear.

In this work, we report the healthy human upper airways in dorsal noncartilage regions contain sporadic poorly differentiated patches exhibiting profound squamous differentiation. Further studies suggest that human airway basal cells are able to undergo reversible squamous differentiation in response to prolonged Wnt stimulation. In addition, we demonstrate that squamous epithelial cells, compared with their isogenic pseudostratified counterparts, have increased glycolysis, compromised epithelial barrier integrity, and impaired host innate immunity.

Methods

Detailed information on materials and methods is available in the data supplement.

Results

Healthy Human Conducting Airways Contain Sporadic Poorly Differentiated Patches in Posterior Regions That Manifest Features of Squamous Differentiation

KRT13+ cells (or hillock cells) have been reported in the mouse trachea, where normal mucociliary airway epithelial cells are replaced by KRT13-positive squamous-like cells (8). By examining histological sections of the conducting airways of healthy donors, we observed similar poorly differentiated epithelial patches that intermittently distribute in dorsal noncartilage regions (Figure 1A). The epithelial cells in this region lack cilia but have a flat squamous-like cell surface (Figure 1A). The staining of lineage markers confirmed that the poorly differentiated patches are absent of ciliated cells and goblet cells (Figures 1B and 1C). In addition, the KRT8+ cell layer is reduced; KRT5+ and p63+ basal cells are expanded; cell turnover is increased in these regions (Figures 1D, 1F, and 1G). Remarkably, profound increases in KRT13+ cells were detected (Figures 1D and 1E), suggesting that cells in these regions adopt squamous cell differentiation. We have examined multiple independent healthy human airways, and KRT13+ squamous patches lacking normal airway epithelial differentiation were detected (Figure 1E; see Figures E1A–E1C in the data supplement). In addition, KRT13+ squamous patches were also detected on the tracheal sections of wild-type mice, rabbits, and pigs (see Figure E1D), suggesting that the presence of KRT13+ squamous patches in healthy upper airways is conserved across species. To determine if the airway basal cells in poorly differentiated regions are intrinsically different, we isolated airway basal cells from the ventral cartilage regions (containing normal mucociliary epithelia) and dorsal noncartilage regions (containing normal mucociliary epithelia and squamous epithelia) for in vitro characterization (see Figure E2A). Airway basal cells were cultured and expanded using the method reported previously (12, 13). Under a bright-field microscope, the morphology of airway basal cells from both regions was indistinguishable (see Figure E2B). The population doubling time calculated over six passages at a 1:8 splitting ratio (three doublings per passage) showed that they had a similar cycling speed (see Figure E2C). When differentiated on air–liquid interface (ALI) culture, airway basal cells from both regions gave rise to ciliated cells and goblet cells with a similar efficiency (see Figure E2D). In both cases, minimal KRT13+ cells were detected (see Figure E2E). Inability to recapitulate squamous differentiation in vitro suggested that there is likely no intrinsic alteration in underlying basal cells. This finding agrees with a recent finding that mouse tracheal basal cells isolated from ventral and dorsal regions did not show differences in cell differentiation in vitro (11), although a recent study suggested otherwise, that the functional heterogeneity of regionally distinct airway basal cells could be maintained when examined in vitro (14).

Figure 1.

Healthy human conducting airway contains sporadic poorly differentiated epithelial patches that manifest features of squamous differentiation. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining suggests that the dorsal noncartilage region of a healthy conducting airway contains patches of poorly differentiated epithelial cells lacking cilia. Scale bars, 5 mm and 250 μm. (B) Representative staining of AcTub (acetylated tubulin) (ciliated cells) and MUC5AC (goblet cells) on normal airway epithelial regions and poorly differentiated regions. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Quantification of ciliated cells and goblet cells in normal airway epithelial regions and poorly differentiated regions. The differentiation index of ciliated cells was calculated as the percentage of luminal epithelial cell layer covered by AcTub immunopositivity. The differentiation index of goblet cells was calculated as total MUC5AC+ goblet cells per 1 cm epithelial length. Ten nonoverlapping areas for each donor were imaged and quantified at 20× objective (mean ± SD; n = 10; ***P ⩽ 0.001). (D) Representative staining of KRT8 (keratin 8), KRT5, KRT13, p63, and Ki67 on normal airway epithelial cell regions and poorly differentiated regions. Scale bars, 20 μm. (E–G) Quantification of KRT13+ cells (E), p63+ cells (F), and Ki67+ cells (G) in normal airway epithelial cell regions and poorly differentiated regions. The cells were scored by total number of positive cells per 1 cm epithelial length. Ten nonoverlapping areas were imaged at 20× objective and grouped together for quantification (mean ± SD; n = 10; ***P ⩽ 0.001).

Wnt Signaling Activation Diverts Pseudostratified Airway Differentiation to the Squamous Program

To identify the possible mechanism underlying the progenitor lineage choice between pseudostratified and squamous cell types, we performed a screen on a panel of signaling modulators that are known to be implicated in cell proliferation and differentiation (see Table E1). In brief, human airway basal cells isolated from a healthy donor at passage 2 were seeded on Transwell plates (Corning). Various signaling pathway modulators (growth factors, cytokines, or small molecules) were added at Day 1 of ALI culture, and KRT13 staining was performed at Day 14 to discern the squamous differentiation. The result suggested that Wnt signaling agonists (CHIR99021 and BIO) strongly promoted the generation of KRT13+ cells (Figure 2A). Other pathways we have tested (either activation or inhibition) have weak or no such effect, including pathways such as EGF (epidermal growth factor) and p38/MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathways that have been implicated in cigarette smoke–induced bronchial epithelial squamous metaplasia (15–17). Thus, we narrowed our focus to the study of Wnt signaling activation and its impact on human airway squamous differentiation. Whole-mount staining of ALI culture confirmed that 2 μM CHIR99021 treatment significantly suppressed the generation of AcTub+ (acetylated tubulin) ciliated cells and MUC5AC+ goblet cells from human airway basal cells but drastically induced KRT13+ squamous epithelial cells (Figure 2B). In addition, CHIR99021–ALI culture was also positive for additional squamous markers, such as KRT10, KRT6A, IVL (involucrin), and KRT78 (see Figure E3A). The staining on ALI cross-sections further confirmed that 2 μM CHIR99021 treatment led to the loss of pseudostratified differentiation marker KRT8, accompanied by p63+ and KRT5+ basal cell hyperplasia, rapid cellular turnover, and KRT13+ squamous cell remodeling (see Figure E3B). Multiple independent basal cell lines (n = 6) have been tested in numerous repeated experiments, and similar results were observed (Figures 2C–2F). Bulk RNA sequencing analysis was performed to investigate transcriptional profiles in response to Wnt activation. CHIR99021–ALI populations have distinct principal component analysis patterns compared with control ALI populations (Figure 2G). Differentially expressed genes in a pairwise comparison (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.01) suggested that CHIR99021 treatment leads to increased expression of the squamous cell–specific keratins (such as KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT6C, KRT16, and KRT13) and the squamous protein components that are often found in the skin and esophagus (such as IVL and DSC2 [desmocollin 2]). Conversely, the transcript amounts of the genes associated with mucociliary airway epithelial cells (such as LDLRAD1 [low density lipoprotein receptor class A domain containing 1], ALDH3B1 [aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member B1], CTGF [connective tissue growth factor], CCDC33 [coiled-coil domain containing 33], MUC15 [mucin 15, cell surface associated], SCGB3A1 [secretoglobin family 3A member 1], and DNAH9 [dynein axonemal heavy chain 9]) are greatly downregulated (Figure 2H). In silico analysis also provided a potential mechanism underlying squamous cell differentiation induced by CHIR99021 treatment. Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that epithelial populations in the squamous condition were enriched with pathways associated with keratinocyte differentiation, cornification, skin development, and microtubules rearrangement (FDR < 0.01; Figure 2I). In contrast, pathways related to cilia architecture organization, elongation, and transportation were downregulated (FDR < 0.01; Figure 2J).

Figure 2.

Wnt signaling activation diverts mucociliary differentiation to the squamous program from normal human airway basal cells. (A) Airway basal cells isolated from a healthy donor at early passage (passage 2) were seeded on Transwell plates for air–liquid interface (ALI) differentiation. On Day 1, various small molecule compounds and growth factors (detailed information on compounds and factors is listed in Table E1) were added to the ALI medium. ALI membranes were fixed at Day 14 for KRT13 staining. The quantification of squamous differentiation was scored as the percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity/image area (mean ± SD; n = 3 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). (B) Whole-mount staining of AcTub+ ciliated cells, MUC5AC+ goblet cells, and KRT13+ squamous cells on a representative ALI culture generated in normal ALI condition or ALI condition containing 2 μM CHIR99021. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C–F) Quantification of ciliated cells (C), club cells (D), goblet cells (E), and squamous cells (F) on the basis of whole-mount staining. In total, six airway basal cells isolated from independent donors were tested. For each donor, multiple experiments were performed. All data were grouped for analysis (mean ± SD; n = 30; ***P ⩽ 0.001). (G) Transcriptional profile analysis revealed that control ALI and CHIR99021-treated ALI populations have distinct PC analysis patterns. (H) Differentially expressed genes in a pairwise comparison suggested that CHIR99021-treated ALI populations were enriched with squamous cell differentiation gene expression with greatly downregulated gene expression for mucociliary differentiation. (I and J) Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that pathways for epidermal development and squamous differentiation (I) were upregulated, while pathways for cilia organization, assembly, and function (J) were downregulated in CHIR99021–ALI culture. ALDH3B1 = aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member B1; CCDC33 = coiled-coil domain containing 33; CCSP = club cell secretory protein; CTGF = connective tissue growth factor; DNAH9 = dynein axonemal heavy chain 9; DSC2 = desmocollin 2; IVL = involucrin; LDLRAD1 = low density lipoprotein receptor class A domain containing 1; MUC15 = mucin 15, cell surface associated; NES = normalized enrichment score; PC = principal component; SCGB3A1 = secretoglobin family 3A member 1.

Persistent WNT Signaling Activation Is Required to Sustain Squamous Differentiation from Human Airway Basal Cells

Airway epithelial cells can secrete Wnt ligands as autocrine signals to support cell proliferation and differentiation. As such, β-catenin activity was reported to increase in the early proliferative stage of human airway ALI cultures (18). Despite this transient increase in β-catenin activity, mucociliary differentiation took place afterward (18). Similarly, Wnt signaling was transiently activated in mouse tracheal basal cells within 48 hours after SO2 injury but decreased to baseline level by 72 hours after injury, before differentiation commenced (19). Transient Wnt signaling activation was also detected in TOPgal β-catenin reporter mice after injury (20, 21). Again, ciliated cells and club cells were generated to replace the lost luminal cells in these studies. We reason that airway basal cells, as stem cells of pseudostratified tissues, default to mucociliary differentiation. Thus, transient Wnt activation in airway basal cells might not be sufficient to change the cellular context to take an alternative differentiation path. To examine if this is the case, we dosed human airway basal cells with 2 μM CHIR99021 at different stages and for various durations during ALI culture (Figure 3A). KRT13+ cell production was quantified at Day 14 to score the degree of squamous differentiation. The result confirmed that prolonged CHIR99021 treatment, particularly during ALI Days 0–7, is necessary for squamous differentiation (Figure 3A). In addition to the duration, the concentration of CHIR99021 is also a critical factor in supporting squamous differentiation. We differentiated human airway basal cells with an increasing CHIR99021 dose. The results suggested that CHIR99021 promotes squamous differentiation at the expense of mucociliary differentiation in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 3B and 3C). Although CHIR99021 has been widely used in numerous studies to activate the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, it is a primary GSK-3–specific inhibitor and might stabilize other factors besides β-catenin. To verify if the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is indeed a driving mechanism for squamous differentiation, we activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling via lentiviral delivery of a constitutively active form of β-catenin (pLV–β-catenin–DN90) (22) (see Figures E4A and E4B). The results suggested that airway basal cells expressing β-catenin–DN90 generated squamous epithelial cells at baseline and showed an increased sensitivity to CHIR99021 stimulation (see Figures E4C and E4D). To demonstrate that the timing of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation is critical for this process, we also tested the effect of doxycycline-inducible expression of β-catenin mutant (pTF–β-catenin–deltaN45) (23). The result confirmed that the treatment of doxycycline during the first but not the second week of ALI differentiation induces KRT13+ squamous cell production (Figures 3D and 3F). Thus, we concluded that prolonged Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation, particularly during the early differentiation stage, is required to initiate and sustain squamous cell fate from human airway basal cells.

Figure 3.

Persistent WNT signaling activation is required to sustain squamous differentiation from human airway basal cells (BCs). (A) Healthy human airway BCs were dosed with 2 μM CHIR99021 at different stages and for various duration during ALI culture. KRT13+ cell production was quantified at 14 days to score the degree of squamous differentiation (percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity/image area) (mean ± SD; n = 3 independent experiments). (B) Human airway BCs were differentiated with increasing concentrations of CHIR99021. The generation of KRT13+ squamous cells and AcTub+ ciliated cells was quantified on the basis of whole-mount staining (scored as percentage of lineage immunopositivity/image area) (mean ± SD; n = 9 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). (C) Whole-mount staining of KRT13, AcTub, and MUC5AC on a representative ALI culture differentiated with increasing concentrations of CHIR99021. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Human airway BCs infected with lentiviral pTF–control or pTF–Flag–β-catenin–DN45 were differentiated with various duration of Dox treatment. (E) Whole-mount staining of KRT13 and Flag on a representative ALI culture generated as described in D. (F) Quantification of squamous cells (percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity area/image area) on ALI culture generated as described in D (mean ± SD; n = 6 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). Scale bars, 200 μm. (G and H) Quantification of squamous cells (percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity area/image area) (G) and cell proliferation (total Ki67+ cell number/image area) (H) on ALI culture generated in the control condition, 2 μM CHIR99021, or 2 μM CHIR99021 plus 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 (mean ± SD; n = 10 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). (I) Quantification of squamous differentiation (percentage KRT13 immunopositivity area/image area) from human, mouse, rabbit, and pig airway BCs in control and in the presence of 2 μM CHIR99021 (mean ± SD; n = 8 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). D = Day; Dox = doxycycline; TGFβ1 = transforming growth factor-β1.

Wnt signaling activation is known to stimulate cell proliferation. Growing evidence suggests that cell proliferation often antagonizes differentiation, probably because of the competition of energy utility. In agreement, squamous patches in human airways and hillock regions in mouse trachea are associated with high Ki67 numbers (Figure 1G) (8). Stratified epithelial tissues such as skin and esophagus often have higher cell turnover than pseudostratified tissues such as the trachea. To examine if increased cell turnover contributes to squamous differentiation, we examined whether TGF-β (transforming growth factor-β) treatment was able to block the effect of CHIR99021. The result confirmed that treatment of TGF-β completely curbed cell proliferation, consistent with our previous report that TGF-β/SMAD signaling inhibition is required for epithelial cell proliferation (13). However, it failed to prevent the squamous differentiation induced by CHIR99021 (Figures 3G and 3H; see Figure E5A). Thus, squamous differentiation was not driven by elevated cell proliferation but rather induced by other CHIR99021-initiated downstream effects. CHIR99021-induced squamous differentiation does not permanently alter basal cell functions. When CHIR99021 was withdrawn and the ALI cultures were returned to normal conditions, mucociliary differentiation was restored over time (see Figure E5B). In addition, airway basal cells isolated from squamous CHIR99021–ALI culture generated normal airway epithelial cells in the next round of ALI differentiation if CHIR99021 was absent (data not shown). As KRT13-expressing patches are identified in tracheal tissues of nonhuman species (see Figure E1D), we also examined if CHIR99021 could promote squamous differentiation from tracheal basal cells of these animals. Unexpectedly, we noticed that pig tracheal basal cells exhibited moderate sensitivity, whereas mouse and rabbit tracheal basal cells were refractory to CHIR99021 stimulation in generating KRT13+ squamous cells (Figure 3I; see Figure E5C), even when we increased CHIR99021 concentration up to 20 μM, the highest dose the cells could tolerate (data not shown). In addition, overexpression of β-catenin–DN90 also fails to promote squamous differentiation from mouse and rabbit tracheal basal cells (data not shown). It is possible that additional mechanisms beyond Wnt signaling activation are required to induce the squamous cell fate from mouse and rabbit airway basal cells. Alternatively, these species exhibit distinct mechanisms from humans in airway squamous differentiation.

Multiple Mechanisms, Including Enhanced Glycolysis, Are Implicated in Airway Squamous Differentiation

To examine if the Wnt–β-catenin pathway is dispensable for squamous differentiation, we knocked down β-catenin in human airway basal cells (Figure 4A). Airway basal cells without β-catenin expression could maintain characteristic stem cell morphology and replicate with a similar speed to control basal cells (data not shown). However, β-catenin knockdown airway basal cells seem to have lower airway differentiation efficiency (see Figure E6A), suggesting that the Wnt–β-catenin pathway is not necessary for human airway cell stemness but is critical for mucociliary differentiation for regeneration, in agreement with prior findings (18). Surprisingly, β-catenin knockdown failed to abrogate squamous differentiation induced by CHIR99021 (Figures 4B and 4C). In addition, a Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitor (IWR-1) only mildly decreased the CHIR9902 effect in inducing squamous differentiation (see Figure E6B). Furthermore, Wnt3A, one of the most highly studied canonical Wnt ligands to activate Wnt/β-catenin pathways, has a weak ability to promote KRT13 squamous differentiation from airway basal cells (see Figure E6B). These observations suggest that in addition to β-catenin–dependent signaling, other CHIR99021-exerted downstream events are involved in airway squamous differentiation. We thus screened various growth factors and pathway modulators to identify factors that could antagonize the effect of CHIR99021. Most factors we have examined did not influence CHIR99021-induced squamous differentiation (data not shown). Interestingly, we identified that the PKC agonist 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, which is involved in mediating Wnt/Ca2+ noncanonical pathway, strongly suppresses squamous differentiation induced by CHIR99021 (Figure 4D; see Figure E6C). Canonical Wnt signaling and noncanonical Wnt signaling have been reported to mutually antagonize each other. Indeed, RNA sequencing analysis also confirmed that Wnt canonical pathway signatures were upregulated whereas noncanonical pathways pathway signatures were downregulated in CHIR99021–ALI cell populations (see Figures E6D–E6F). Wnt pathways are known to regulate key metabolic signaling pathways such as mTOR and insulin signaling. As expected, we also observed that rapamycin (a classic mTOR inhibitor), metformin (a widely used drug that reduces cell glucose metabolism and mitochondrial respiration), and ZSTK474 (a PI3K pathway inhibitor) exhibited inhibitory effects by reducing KRT13+ cell generation (Figure 4D; see Figure E6C). Glucose is an important energy substrate. Metabolites of glucose, in particular glucose-6-phosphate, activate the mTOR complex and PI3K pathway (24). We noticed that several common ALI media we and other researchers use contain high glucose concentrations (see Figure E7A). For example, PneumaCult-ALI medium (STEMCELL Technologies) contains 17.5 mM glucose. However, healthy patients and wild-type mice normally have fasting plasma glucose concentrations less than 100 mg/dl (5.6 mM). A fasting plasma glucose concentration equal to or greater than 126 mg/dl is diagnostic of diabetes. On the basis of this information, airway basal cells are routinely differentiated in “highly diabetic” glucose conditions. To examine if high glucose availability would influence CHIR99021-induced squamous differentiation, we made two modified ALI media by diluting PneumaCult-ALI medium using normal Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 (17.5 mM glucose) or glucose-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 (0 mM glucose). These two modified ALI media have the same formulation, except that the latter contains 17.5 mM glucose, whereas the former contains 5.6 mM glucose (physiological glucose concentration). Six independent healthy airway basal cells were tested. As we expected, more KRT13+ cells were produced in the 17.5-mM than in 5.6-mM glucose condition after CHIR99021 treatment (Figure 4E; see Figure E7B). In agreement, comparative transcriptomic analysis of airway epithelial cells (control–ALI) and squamous epithelial cells (CHIR99021–ALI) confirmed that many genes associated with glucose uptake and glycolysis are greatly upregulated (Figures 4F and 4G). To further investigate if increased glycolysis contributes to airway epithelial squamous differentiation, we examined if treatment with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) was able to inhibit the effect of CHIR99021. 2-DG is a derivative of glucose in which the 2-hydroxyl group is replaced by hydrogen; as such, it cannot undergo further glycolysis (25). As expected, 2-DG significantly decreased the degree of squamous differentiation (Figure 4H; see Figure E7C). In conclusion, we showed that increased metabolism, particularly glycolysis, sensitizes airway basal cells for squamous differentiation. In addition, imbalanced canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling also contributes to airway squamous differentiation.

Figure 4.

CHIR99021-induced squamous differentiation is associated with increased glycolysis. (A) Western blot analysis of short hairpin (sh)–control and sh–β-catenin (knockdown) human airway basal cells. (B) Whole-mount staining of KRT13 on a representative ALI culture of sh-control and sh–β-catenin human airway basal cells in control condition and in 2 μM CHIR99021. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Quantification of squamous cells (percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity/image area) generated from sh-control and sh–β-catenin human airway basal cells in control condition and in 2 μM CHIR99021 (mean ± SD; n = 6 independent experiments). (D and E) Quantification of squamous cells (percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity/image area) from human airway basal cells generated in indicated conditions [CHIR99021, 2 μM; TPA, 0.1 μM; metformin, 100 μM; rapamycin, 5 nM; ZSTK474, 0.5 μM (D) and 17.5 mM and 5.6 mM glucose (E)] (mean ± SD; n = 6 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). (F and G) Transcriptomic analysis (F) of airway epithelial cells and CHIR99021-induced isogenic squamous epithelial cells revealed that many genes associated with glucose uptake and glycolysis are greatly upregulated (G). (H) Quantification of squamous cells (percentage of KRT13 immunopositivity/image area) generated from human airway basal cells in control condition and in 2 μM CHIR99021 with or without 10 mM 2G (mean ± SD; n = 6 independent experiments; ***P ⩽ 0.001). 2-DG = 2-deoxy-d-glucose; AK-3 = adenylate kinase 3; ALDOA = aldolase, fructose-bisphosphate A; DDIT4 = DNA damage inducible transcript 4; ENO1 = enolase 1; FAM3C = FAM3 metabolism regulating signaling molecule C; GPC1 = glypican 1; GPI = glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; HK2 = hexokinase 2; HKDC1 = hexokinase domain containing 1; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; PCK2 = phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2, mitochondrial; PFKFB3 = 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3; PFKL = phosphofructokinase, liver type; PFKP = phosphofructokinase, platelet; PGAM1 = phosphoglycerate mutase 1; PGK1 = phosphoglycerate kinase 1; PKM = pyruvate kinase M1/2; PLOD2 = procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2; SLC2 = solute carrier family 2; SLC5 = solute carrier family 5; STC = stanniocalcin; TPA = 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

Squamous Epithelial Cells Have Disrupted Epithelial Barrier Function, Undergo Spontaneous Unjamming, and Mount Enhanced Inflammatory Responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection

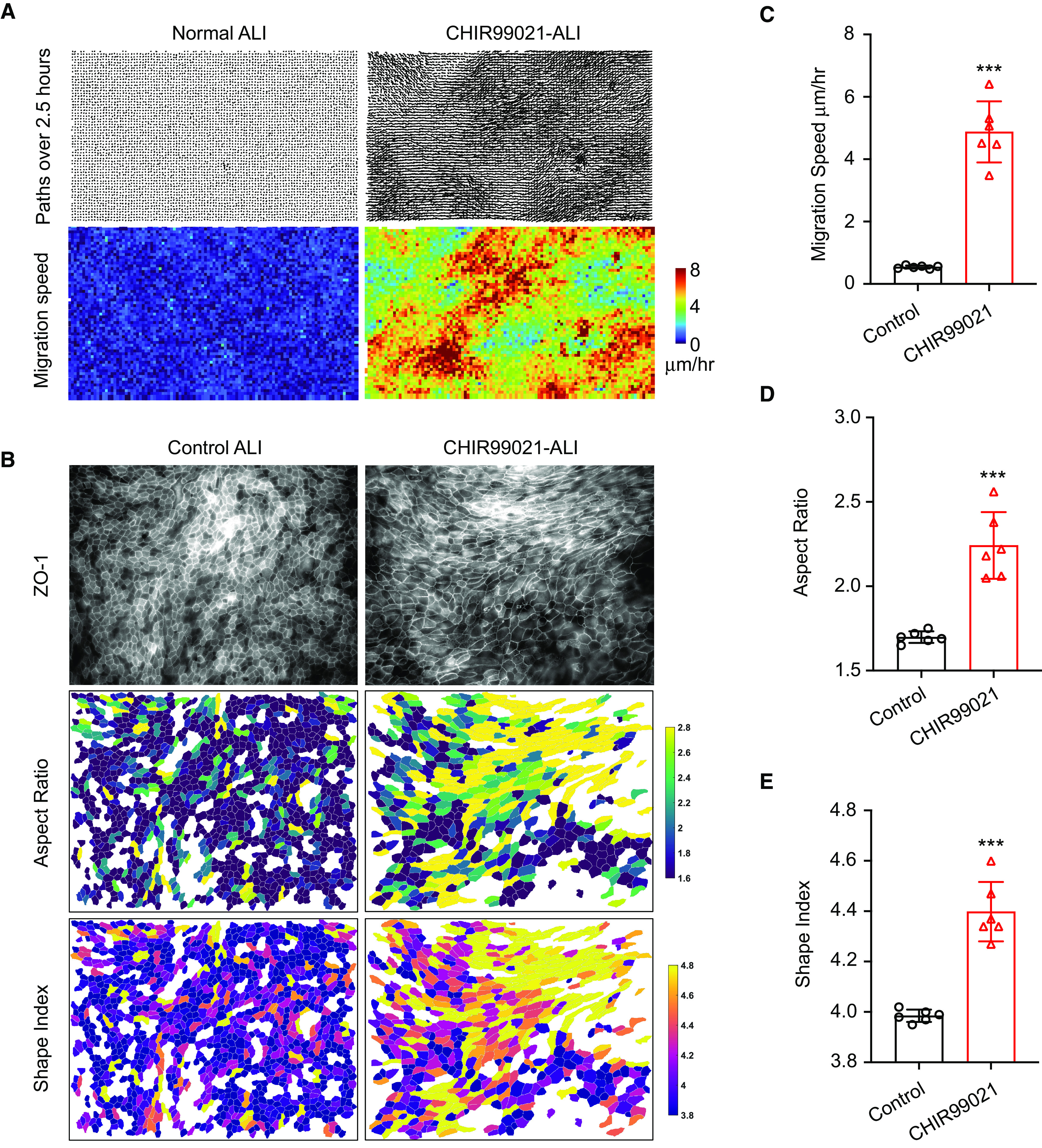

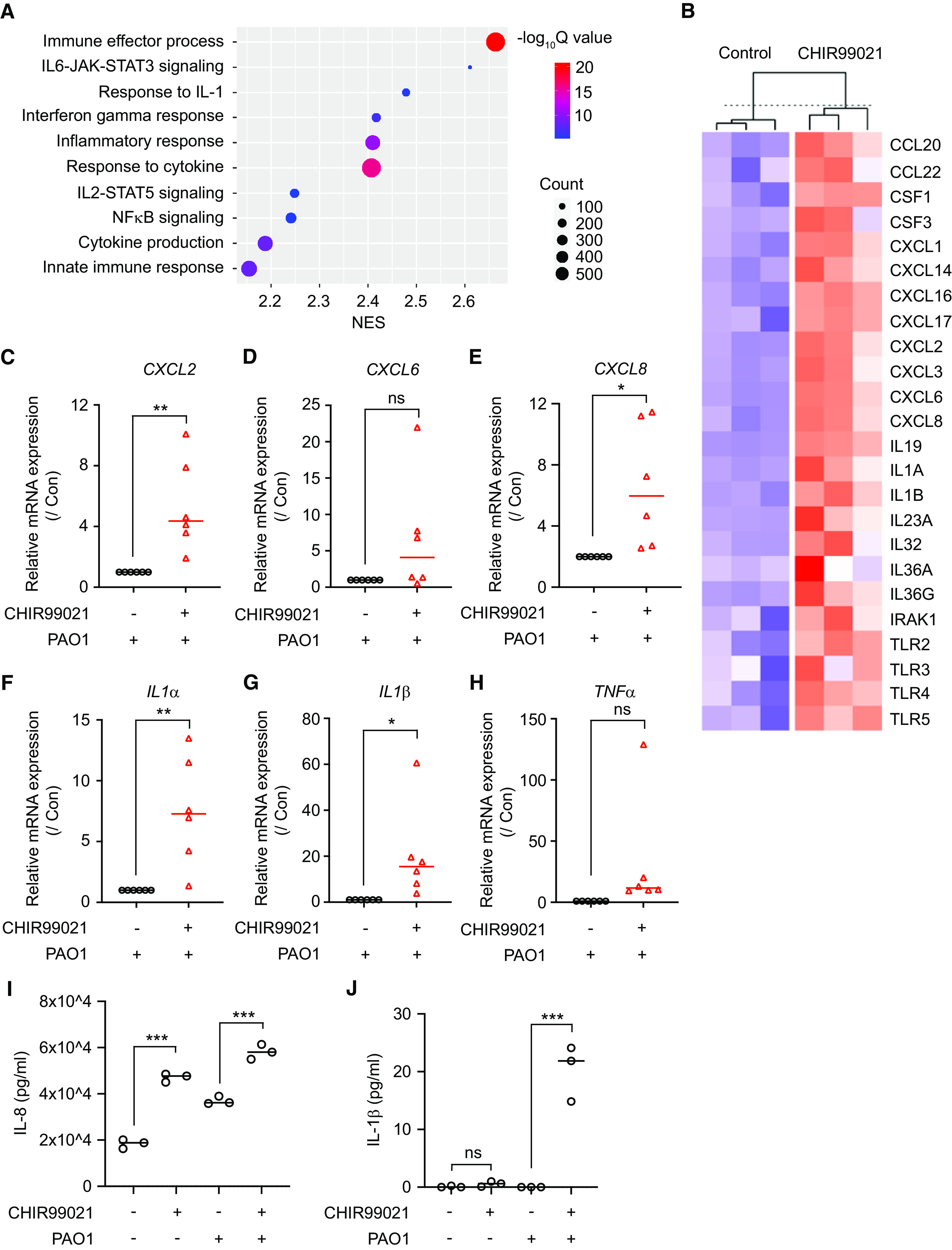

Next, we examined the potential physiopathological consequence of airway squamous differentiation. Mucociliary clearance, barrier function, and inflammatory responses are the primary components of innate immunity of airway epithelia. By using micro–optical computed tomography imaging, we detected those squamous epithelial cells completely lacked mucociliary clearance, consistent with the loss of ciliated cells (data not shown). In addition, the staining of tight junction protein ZO-1 (zona occludens 1) on squamous epithelia was diffuse and disorganized, in contrast to the homogeneous cobblestone pattern on normal airway epithelia (see Figure E8A). Furthermore, those squamous cells have decreased transepithelial electrical resistance and increased paracellular transport of the protein HRP and FITC-inulin (see Figures E8B–E8D). We also quantitively traced CHIR99021–ALI and control–ALI in parallel. The result suggested that squamous airway epithelial cells were profoundly unjammed, while normal airway epithelial cells were stationary, as expected (Figures 5A–5E; see Videos E1 and E2). Epithelial unjamming, or collective epithelial cellular migration, has been identified when cells are immature or under compressive stress (26, 27), after viral infection (28), and after exposure to ionizing radiation (29). In addition, airway epithelial cells isolated from patients with asthma and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are also unjammed (27, 30). Consistently, RNA sequencing data revealed that the gene signature related to oxidative cell stress, hypoxia, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and TGF-β signaling was upregulated in squamous epithelial cells (see Figure E8E). Unjammed behavior of squamous cells also indicated that they could be in an “inflammatory” state. In agreement, we observed that squamous epithelial cells exhibited low-grade baseline inflammation (Figures 6A and 6B). Multiple inflammatory pathways were significantly upregulated, and several cytokines and chemokines were expressed in squamous cells without infection (Figures 6A and 6B; see Figures E9A–E9F). We then analyzed the consequence of infection on isogenic pseudostratified airway versus squamous. After exposure to pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, the squamous cells mounted a stronger inflammatory response by producing higher mRNA concentrations of proinflammatory mediators, including CXCL2, CXCL8, CXCL6, IL1α, IL1β, and TNFα (Figures 6C–6H). ELISA analysis confirmed that squamous cells also secreted higher amounts of IL-8 (CXCL8) and IL-1β protein after 4 hours of P. aeruginosa PAO1 infection (Figures 6I and 6J). Neutrophil infiltration is a hallmark of mucosal infectious disease. Therefore, we also quantified neutrophils that migrate through epithelium as an additional parameter to inform the potential magnitude of inflammatory responses (see Figure E9G). We observed that an increased number of neutrophils migrated through squamous epithelial cells in response to P. aeruginosa PAO1 infection but not to the neutrophil chemoattractant LTB4 (leukotriene B4) (see Figure E9H). It suggested that squamous epithelial cells, compared with normal airway epithelial cells, have higher infection-associated inflammation (more neutrophil infiltration), whereas both cell types are equally permissive to neutrophil transepithelial migration in response to an applied chemotactic gradient (LTB4). In summary, these data suggest that squamous differentiation is associated with a hyperinflammatory phenotype with dysregulated barrier function and innate immunity.

Figure 5.

Squamous differentiation induces spontaneous epithelial unjamming. (A) Representative velocity vector and speed maps of airway epithelial cells in control condition and in CHIR99021-treated condition. (B) Representative images of cell shape analysis and speed analysis of cell migration. (C–E) Average aspect ratio (indicating cell orientation) (D), cell shape index (E), and speed of cell migration (C) (n = 6; two fields of view per well from three independent wells; ***P ⩽ 0.001). ZO-1 = zona occludens 1.

Figure 6.

Squamous epithelial cells have baseline inflammation and mount enhanced inflammatory responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 infection. (A) Transcriptomic analysis suggested that multiple inflammatory pathways were upregulated in CHIR99021-induced squamous epithelial cells. (B) Several cytokines and chemokines were expressed in CHIR99021–ALI culture, suggesting that squamous epithelial cells exhibited low-grade inflammation in an uninfected state. (C–H) Quantitative PCR analysis of CXCL2 (C), CXCL8 (E), CXCL6 (D), IL1α (F), IL1β (G), and TNFα (F) in control ALI culture and CHIR99021 ALI culture after 1 hour of exposure to pathogenic P. aeruginosa PAO1 (mean ± SD; n = 6 independent donors; ns = not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (I and J) ELISA analysis of IL-8 (I) and IL-1β (J) protein secreted from control and CHIR99021–ALI culture after 4 hours of exposure to pathogenic P. aeruginosa PAO1 (mean ± SD; n = 3 experiments; ***P < 0.001). Con = control; CSF = colony stimulating factor; IRAK1 = IL-1 receptor associated kinase 1; TLR = Toll-like receptor.

Discussion

Basal cell hyperproliferation, squamous differentiation, and concomitant loss of ciliated cells are pathogenic cellular changes commonly observed in infectious or inflammation-related injury, early neoplastic lesions, and many respiratory disorders. However, squamous epithelial cells can naturally exist in healthy conducting airways (4–7). Single-cell RNA sequencing analyses have revealed remarkable cellular heterogeneity in homeostatic human airways (6). Our study suggests that at least some cell subpopulations, such as squamous epithelial cells, could reflect the differentiation versatility of basal cells, rather than an intrinsic functional difference. We identified that human airway basal cells isolated from ventral cartilage and dorsal noncartilage regions are morphologically and functionally indistinguishable in vitro. Instead, WNT pathway activation serves as a major driving force in promoting squamous cell fate from airway basal cells. The Wnt signaling pathway is a conserved signaling axis participating in diverse physiological processes such as embryogenesis, as well as the proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration of adult stem/progenitor cells in many organs to ensure homeostasis and appropriate regeneration (31, 32). During lung development, Wnt signals are fluctuated (on and off) to orchestrate lung endoderm commitment, branching morphogenesis, proximal–distal patterning, and alveolarization (33). In adult homeostatic airway epithelial cells, Wnt activation remains low (18, 19). By using in vitro ALI culture as a model of airway epithelial repair from human basal cells, Wnt signaling activation was reported to be amplified in the early proliferation phase but downregulated along the route to terminal differentiation (18). In the SO2 inhalation mouse model, Wnt signaling activation is also transiently increased in tracheal epithelial cells to promote cell proliferation and migration (19–21). However, ciliated cells and club cells are generated to replace the lost luminal cells after the completion of regeneration. These observations indicate that shifting toward squamous differentiation from pseudostratified cell fate requires a drastic adjustment in gene expression and protein synthesis. Accordingly, we demonstrated that a brief CHIR99021 stimulation or activated β-catenin mutant expression is insufficient to sustain squamous differentiation, consistent with a prior report that continuous Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation is required to drive airway basal stem cell hyperproliferation and loss of ciliated cell differentiation (18, 19). Although the Wnt signal recedes rapidly in normal tissue regeneration, Wnt signaling can become constitutively activated in pathogenic conditions such as genetic mutations or chronic environmental perturbations. As a consequence, airway squamous hyperplasia and metaplasia are amplified over disease progression. In addition to airways, Wnt signaling activation seems to promote a squamous program in other organs. For example, it has been reported that overexpression of Wnt ligands or accumulation of β-catenin mutants in mammary and prostate tissues promotes the development of epidermis-like squamous metaplasia from granular cell fate (34–38). Similarly, increased Wnt signaling transdifferentiates type 2 alveolar epithelial cells (cuboidal cells) to alveolar type 1 epithelial cells (squamous-like cells) (39). Further work is needed to uncover if the prolonged Wnt signaling activation functions as a universal mechanism to initiate squamous cell program from nonsquamous tissues or cells.

Several additional observations revealed by this study merit future investigation. First, although a few poorly differentiated squamous patches could be found in ventral airways, they were spotted mainly in dorsal regions adjacent to smooth muscle membranes, and some were identified in the regions between cartilages. Interestingly, in the nasopharynx, stratified squamous epithelial cells are also identified in the most caudal part, whereas the rostral part is lined with the ciliated columnar epithelium (40). The regionally specific location of squamous cells suggests that these regions may have unique microenvironments or neighboring cells that support squamous differentiation. Furthermore, airway basal cells in these specific places should be actively undergoing de novo differentiation, as we showed that Wnt signaling stimulation drives squamous differentiation from airway basal cells but not from fully differentiated epithelial cells. Cellular resources of Wnt ligands in the human airways have not yet been well explored. In mouse trachea, epithelial cells, immune cells, and mesenchymal cells such as Pdgfrα+ lineage have been reported as critical sources of Wnt ligands after injury and participate in modulating airway regeneration (19, 41, 42). On the basis of the spatial proximity to squamous cells, we speculate that airway smooth cells may serve as an additional Wnt-secreting niche. Indeed, several studies have suggested that airway smooth muscle cells participate in regulating airway regeneration in mouse via paracrine signaling (41, 43, 44). Furthermore, parabronchial smooth muscle hyperplasia is a well-known structural change in airway diseases, accompanied by basal cell hyperplasia, goblet cell hyperplasia, and squamous hyperplasia (45–49), further supporting that smooth muscle cells are a critical cell type for maintaining airway homeostasis and disease pathogenesis.

Second, we identified that airway basal cells of various species show a significant difference in responsiveness to Wnt stimulation for squamous differentiation. Pigs share similar physiological and anatomic features with humans. Accordingly, pig and human tracheal basal cells are comparable for CHIR99021-induced squamous differentiation. In contrast, mouse and rabbit airway basal cells are refractory to squamous differentiation in vitro, suggesting that either additional signals are needed, or a distinct mechanism is responsible for the squamous differentiation in these species.

Third, we observed that the gene signature of glucose uptake and glycolysis is greatly upregulated in CHIR99021-induced squamous epithelial cells. In addition, high glucose exposure primes human airway basal cells for squamous transition. The phenomenon of the shift toward glycolysis as the source of ATP has been well described in cancer cells. Recently, several studies showed that macrophages and airway epithelial cells under stress, unjamming, hypoxia, and infections (such as P. aeruginosa, influenza, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2]) exhibit greater activation of the mTOR pathway, increased glycolytic flux, and inflammatory cytokine production (50–56). It has become evident that patients with obesity or diabetes with hyperglycemia have a higher chance of developing airway diseases and are sensitive to viral and pathogenic respiratory infections (57–59). Thus, further studies are required to examine if humans and animals with hyperglycemia are susceptible to airway squamous remodeling during injury repair and disease pathogenesis. As common laboratory practice, ALI media (commercial or laboratory made) are widely used to support airway epithelial differentiation. However, they often contain glucose concentrations much higher than physiological serum glucose. Recently, a group reported that the choice of differentiation medium significantly affects cell differentiation and response to CFTR (CF transmembrane conductance regulator) modulators (60). Our study further emphasizes that close attention should be paid to avoid high glucose–associated squamous remodeling.

Fourth, we showed that squamous differentiation from healthy airway basal cells is reversible. A recent study suggested that COPD airways harbor a percentage of basal cell clones that naturally give rise to squamous cells in in vitro culture without further treatment (61). This suggests that a subpopulation of airway basal cells in diseased airways have fixed squamous cell fate. On the basis of our study, we speculate that Wnt signaling might be constitutively activated in these basal cell variants. However, COPD is a complicated disease with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes and underlying etiologies. During disease development, COPD airway basal cells may accumulate multiple genetic mutations or epigenetic modifications, which affect not only Wnt signaling but also other pathways and gene expression. That being said, it will be still interesting to test if squamous differentiation from these clone variants can be reversed by the genetic or pharmaceutical inhibition of the Wnt pathway.

Fifth, we showed that squamous cells exhibit impaired barrier functions, spontaneous collective migration, and enhanced inflammatory responses. These properties likely would confer the vulnerability to airway mucosa by increasing the sensitivity of tissue to injurious and inflammatory damage. In COPD and other diseases, squamous remodeling becomes drastic and permanent, and hyperinflammatory features of squamous cells can be important comorbidities in disease severity and outcome. Of note, the observation that squamous epithelial cells secrete IL-1β upon infection is intriguing, as IL-1β secretion requires inflammasome activation and is generally believed to be produced by immune cells. IL-1β has recently emerged as a dominant pathogenic promucin cytokine in chronic and infectious diseases, contributing to mucin hypersecretion and airway obstruction (62, 63). This finding implies that squamous remodeling might further aggravate airway mucous blockage by providing additional IL-1β to airway epithelial cells as paracrine.

Conclusions

Our work unravels a previously uncharacterized mechanism in which prolonged Wnt stimulation interplaying with glycolytic reprogramming drives reversible squamous differentiation from healthy human airway basal cells. However, we acknowledge that other mechanisms might also be implicated in this process, exerting redundant or nonoverlapping roles together with Wnt/β-catenin signaling in inducing squamous differentiation from airway basal cells. Because of pathogenic tendency of squamous differentiation, we advocate that targeting excessive Wnt activation and deregulated glycolysis should be considered to mitigate squamous remodeling and control inflammation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Hui Min Leung (Dr. Guillermo J. Tearney laboratory) for her assistance with micro–optical coherence tomography analysis.

Footnotes

Supported by the Job Research Foundation (H.M.), Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Grant MOU19G0 (H.M.), a Hood Child Health Research Award (H.M.), Harvard Stem Cell Institute Seed Grant SG-0120-19-00 (H.M.), the National Institutes of Health grants R21AR080778 (H.M.), R01AI095338 (B.P.H.), R01HL15967501 and R01HL152293 (J.Q.), T32HL007118 (T.N.P.), R01HL148152 (J.P.) and R01HL154549 (X.A.).

Author Contributions: H.M. and Y.Z. contributed to method optimization, data curation, and analysis. H.M. oversaw project conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, and investigation and also wrote the manuscript. W.W., C.Z., H.L., and X.A. participated in RNA sequencing data analysis. K.E.B. and L.P.H. provided human lung tissue for this work. B.P.H., T.L., and S.R.T. assisted with epithelial barrier function analysis, cytokine ELISAs, and neutrophil transmigration assay. T.-K.N.P. and J.-A.P. assisted with the epithelial unjamming assay. P.H.L., J.X., A.L., and J.Q. participated in data interpretation and discussion. All authors helped with manuscript editing and approved the final version to be published.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0299OC on February 8, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Ruysseveldt E, Martens K, Steelant B. Airway basal cells, protectors of epithelial walls in health and respiratory diseases. Front Allergy . 2021;2:787128. doi: 10.3389/falgy.2021.787128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu M, Zhang X, Lin Y, Zeng Y. Roles of airway basal stem cells in lung homeostasis and regenerative medicine. Respir Res . 2022;23:122. doi: 10.1186/s12931-022-02042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plasschaert LW, Žilionis R, Choo-Wing R, Savova V, Knehr J, Roma G, et al. A single-cell atlas of the airway epithelium reveals the CFTR-rich pulmonary ionocyte. Nature . 2018;560:377–381. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0394-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruiz García S, Deprez M, Lebrigand K, Cavard A, Paquet A, Arguel MJ, et al. Novel dynamics of human mucociliary differentiation revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing of nasal epithelial cultures. Development . 2019;146:dev177428. doi: 10.1242/dev.177428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chua RL, Lukassen S, Trump S, Hennig BP, Wendisch D, Pott F, et al. COVID-19 severity correlates with airway epithelium-immune cell interactions identified by single-cell analysis. Nat Biotechnol . 2020;38:970–979. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0602-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deprez M, Zaragosi LE, Truchi M, Becavin C, Ruiz García S, Arguel MJ, et al. A single-cell atlas of the human healthy airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;202:1636–1645. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201911-2199OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vieira Braga FA, Kar G, Berg M, Carpaij OA, Polanski K, Simon LM, et al. A cellular census of human lungs identifies novel cell states in health and in asthma. Nat Med . 2019;25:1153–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Montoro DT, Haber AL, Biton M, Vinarsky V, Lin B, Birket SE, et al. A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature . 2018;560:319–324. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Travaglini KJ, Nabhan AN, Penland L, Sinha R, Gillich A, Sit RV, et al. A molecular cell atlas of the human lung from single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature . 2020;587:619–625. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2922-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoegger MJ, Fischer AJ, McMenimen JD, Ostedgaard LS, Tucker AJ, Awadalla MA, et al. Impaired mucus detachment disrupts mucociliary transport in a piglet model of cystic fibrosis. Science . 2014;345:818–822. doi: 10.1126/science.1255825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tadokoro T, Tanaka K, Osakabe S, Kato M, Kobayashi H, Hogan BLM, et al. Dorso-ventral heterogeneity in tracheal basal stem cells. Biol Open . 2021;10:bio058676. doi: 10.1242/bio.058676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levardon H, Yonker LM, Hurley BP, Mou H. Expansion of airway basal cells and generation of polarized epithelium. Bio Protoc . 2018;8:e2877. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mou H, Vinarsky V, Tata PR, Brazauskas K, Choi SH, Crooke AK, et al. Dual SMAD signaling inhibition enables long-term expansion of diverse epithelial basal cells. Cell Stem Cell . 2016;19:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou Y, Yang Y, Guo L, Qian J, Ge J, Sinner D, et al. Airway basal cells show regionally distinct potential to undergo metaplastic differentiation. eLife . 2022;11:e80083. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Du C, Lu J, Zhou L, Wu B, Zhou F, Gu L, et al. MAPK/FoxA2-mediated cigarette smoke-induced squamous metaplasia of bronchial epithelial cells. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis . 2017;12:3341–3351. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S143279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaykhiev R, Zuo WL, Chao I, Fukui T, Witover B, Brekman A, et al. EGF shifts human airway basal cell fate toward a smoking-associated airway epithelial phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2013;110:12102–12107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303058110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zuo W-L, Yang J, Gomi K, Chao I, Crystal RG, Shaykhiev R. EGF-amphiregulin interplay in airway stem/progenitor cells links the pathogenesis of smoking-induced lesions in the human airway epithelium. Stem Cells . 2017;35:824–837. doi: 10.1002/stem.2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmid A, Sailland J, Novak L, Baumlin N, Fregien N, Salathe M. Modulation of Wnt signaling is essential for the differentiation of ciliated epithelial cells in human airways. FEBS Lett . 2017;591:3493–3506. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aros CJ, Vijayaraj P, Pantoja CJ, Bisht B, Meneses LK, Sandlin JM, et al. Distinct spatiotemporally dynamic Wnt-secreting niches regulate proximal airway regeneration and aging. Cell Stem Cell . 2020;27:413–429.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brechbuhl HM, Ghosh M, Smith MK, Smith RW, Li B, Hicks DA, et al. β-Catenin dosage is a critical determinant of tracheal basal cell fate determination. Am J Pathol . 2011;179:367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giangreco A, Lu L, Vickers C, Teixeira VH, Groot KR, Butler CR, et al. β-Catenin determines upper airway progenitor cell fate and preinvasive squamous lung cancer progression by modulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Pathol . 2012;226:575–587. doi: 10.1002/path.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher JL, Shibue T, Tischler V, Reinhardt F, et al. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell . 2012;148:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boitard M, Bocchi R, Egervari K, Petrenko V, Viale B, Gremaud S, et al. Wnt signaling regulates multipolar-to-bipolar transition of migrating neurons in the cerebral cortex. Cell Rep . 2015;10:1349–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell . 2017;168:960–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wick AN, Drury DR, Nakada HI, Wolfe JB. Localization of the primary metabolic block produced by 2-deoxyglucose. J Biol Chem . 1957;224:963–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Park J-A, Kim JH, Bi D, Mitchel JA, Qazvini NT, Tantisira K, et al. Unjamming and cell shape in the asthmatic airway epithelium. Nat Mater . 2015;14:1040–1048. doi: 10.1038/nmat4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park J-A, Atia L, Mitchel JA, Fredberg JJ, Butler JP. Collective migration and cell jamming in asthma, cancer and development. J Cell Sci . 2016;129:3375–3383. doi: 10.1242/jcs.187922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhodes C, Mitchel J, Bochkov YA, Hirsch R, Lan B, Stancil I, et al. Rhinovirus induces dysmaturity and unjamming of normal and asthmatic human bronchial epithelial layers [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2017;195:A7339. [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Sullivan MJ, Mitchel JA, Das A, Koehler S, Levine H, Bi D, et al. Irradiation induces epithelial cell unjamming. Front Cell Dev Biol . 2020;8:21. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ghosh B, Nishida K, Chandrala L, Mahmud S, Thapa S, Swaby C, et al. Epithelial plasticity in COPD results in cellular unjamming due to an increase in polymerized actin. J Cell Sci . 2022;135:jcs258513. doi: 10.1242/jcs.258513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell . 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steinhart Z, Angers S. Wnt signaling in development and tissue homeostasis. Development . 2018;145:dev146589. doi: 10.1242/dev.146589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aros CJ, Pantoja CJ, Gomperts BN. Wnt signaling in lung development, regeneration, and disease progression. Commun Biol . 2021;4:601. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02118-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bierie B, Nozawa M, Renou JP, Shillingford JM, Morgan F, Oka T, et al. Activation of β-catenin in prostate epithelium induces hyperplasias and squamous transdifferentiation. Oncogene . 2003;22:3875–3887. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gounari F, Signoretti S, Bronson R, Klein L, Sellers WR, Kum J, et al. Stabilization of β-catenin induces lesions reminiscent of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, but terminal squamous transdifferentiation of other secretory epithelia. Oncogene . 2002;21:4099–4107. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miyoshi K, Shillingford JM, Le Provost F, Gounari F, Bronson R, von Boehmer H, et al. Activation of beta -catenin signaling in differentiated mammary secretory cells induces transdifferentiation into epidermis and squamous metaplasias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2002;99:219–224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012414099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miyoshi K, Rosner A, Nozawa M, Byrd C, Morgan F, Landesman-Bollag E, et al. Activation of different Wnt/beta-catenin signaling components in mammary epithelium induces transdifferentiation and the formation of pilar tumors. Oncogene . 2002;21:5548–5556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Teulière J, Faraldo MM, Deugnier MA, Shtutman M, Ben-Ze’ev A, Thiery JP, et al. Targeted activation of β-catenin signaling in basal mammary epithelial cells affects mammary development and leads to hyperplasia. Development . 2005;132:267–277. doi: 10.1242/dev.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abdelwahab EMM, Rapp J, Feller D, Csongei V, Pal S, Bartis D, et al. Wnt signaling regulates trans-differentiation of stem cell like type 2 alveolar epithelial cells to type 1 epithelial cells. Respir Res . 2019;20:204. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1176-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nakano T, Iwama Y, Hasegawa K, Muto H. The intermediate epithelium lining the nasopharynx of the Suncus murinus. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn . 1990;67:169–174. doi: 10.2535/ofaj1936.67.2-3_169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee J-H, Tammela T, Hofree M, Choi J, Marjanovic ND, Han S, et al. Anatomically and functionally distinct lung mesenchymal populations marked by Lgr5 and Lgr6. Cell . 2017;170:1149–1163.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zepp JA, Zacharias WJ, Frank DB, Cavanaugh CA, Zhou S, Morley MP, et al. Distinct mesenchymal lineages and niches promote epithelial self-renewal and myofibrogenesis in the lung. Cell . 2017;170:1134–1148.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moiseenko A, Vazquez-Armendariz AI, Kheirollahi V, Chu X, Tata A, Rivetti S, et al. Identification of a repair-supportive mesenchymal cell population during airway epithelial regeneration. Cell Rep . 2020;33:108549. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Volckaert T, Dill E, Campbell A, Tiozzo C, Majka S, Bellusci S, et al. Parabronchial smooth muscle constitutes an airway epithelial stem cell niche in the mouse lung after injury. J Clin Invest . 2011;121:4409–4419. doi: 10.1172/JCI58097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bara I, Ozier A, Tunon de Lara JM, Marthan R, Berger P. Pathophysiology of bronchial smooth muscle remodelling in asthma. Eur Respir J . 2010;36:1174–1184. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00019810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chung KF. The role of airway smooth muscle in the pathogenesis of airway wall remodeling in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc . 2005;2:347–354. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-028SR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Joubert P, Hamid Q. Role of airway smooth muscle in airway remodeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2005;116:713–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Munakata M. Airway remodeling and airway smooth muscle in asthma. Allergol Int . 2006;55:235–243. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Prakash YS. Emerging concepts in smooth muscle contributions to airway structure and function: implications for health and disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2016;311:L1113–L1140. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00370.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Codo AC, Davanzo GG, Monteiro LB, de Souza GF, Muraro SP, Virgilio-da-Silva JV, et al. Elevated glucose levels favor SARS-CoV-2 infection and monocyte response through a HIF-1α/glycolysis-dependent axis. Cell Metab . 2020;32:437–446.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Doolittle LM, Binzel K, Nolan KE, Craig K, Rosas LE, Bernier MC, et al. Cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine corrects alveolar type II cell mitochondrial dysfunction in influenza-infected mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2022;66:682–693. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2021-0512OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Morris DR, Qu Y, Agrawal A, Garofalo RP, Casola A. HIF-1α modulates core metabolism and virus replication in primary airway epithelial cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Viruses . 2020;12:E1088. doi: 10.3390/v12101088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ramirez-Moral I, Yu X, Butler JM, van Weeghel M, Otto NA, Ferreira BL, et al. mTOR-driven glycolysis governs induction of innate immune responses by bronchial epithelial cells exposed to the bacterial component flagellin. Mucosal Immunol . 2021;14:594–604. doi: 10.1038/s41385-021-00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ren L, Zhang W, Zhang J, Zhang J, Zhang H, Zhu Y, et al. Influenza A virus (H1N1) infection induces glycolysis to facilitate viral replication. Virol Sin . 2021;36:1532–1542. doi: 10.1007/s12250-021-00433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woods PS, Doolittle LM, Rosas LE, Joseph LM, Calomeni EP, Davis IC. Lethal H1N1 influenza A virus infection alters the murine alveolar type II cell surfactant lipidome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2016;311:L1160–L1169. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00339.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhu B, Wu Y, Huang S, Zhang R, Son YM, Li C, et al. Uncoupling of macrophage inflammation from self-renewal modulates host recovery from respiratory viral infection. Immunity . 2021;54:1200–1218.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hulme KD, Yan L, Marshall RJ, Bloxham CJ, Upton KR, Hasnain SZ, et al. High glucose levels increase influenza-associated damage to the pulmonary epithelial-endothelial barrier. eLife . 2020;9:e56907. doi: 10.7554/eLife.56907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nouri-Keshtkar M, Taghizadeh S, Farhadi A, Ezaddoustdar A, Vesali S, Hosseini R, et al. Potential impact of diabetes and obesity on alveolar type 2 (AT2)-lipofibroblast (LIF) interactions after COVID-19 infection. Front Cell Dev Biol . 2021;9:676150. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.676150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang D, Ma Y, Tong X, Zhang Y, Fan H. Diabetes mellitus contributes to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a review from clinical appearance to possible pathogenesis. Front Public Health . 2020;8:196. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Saint-Criq V, Delpiano L, Casement J, Onuora JC, Lin J, Gray MA. Choice of differentiation media significantly impacts cell lineage and response to CFTR modulators in fully differentiated primary cultures of cystic fibrosis human airway epithelial cells. Cells . 2020;9:2137. doi: 10.3390/cells9092137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rao W, Wang S, Duleba M, Niroula S, Goller K, Xie J, et al. Regenerative metaplastic clones in COPD lung drive inflammation and fibrosis. Cell . 2020;181:848–864.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen G, Sun L, Kato T, Okuda K, Martino MB, Abzhanova A, et al. IL-1β dominates the promucin secretory cytokine profile in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest . 2019;129:4433–4450. doi: 10.1172/JCI125669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kato T, Asakura T, Edwards CE, Dang H, Mikami Y, Okuda K, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of mucus accumulation in COVID-19 lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;206:1336–1352. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2606OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]