Abstract

Background:

Variations in dietary intake and environmental exposure patterns of essential and non-essential trace metals influence many aspects of human health throughout the life span.

Objective:

To examine the relationship between urine profiles of essential and non-essential metals in mother-offspring pairs and their association with early dysglycemia.

Methods:

Herein, we report findings from an ancillary study to the international Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow Up Study (HAPO-FUS) that examined urinary essential and non-essential metal profiles from mothers and offspring ages 10-14 years (1012 mothers, 1013 offspring, 968 matched pairs) from 10 international sites.

Results:

Our analysis demonstrated a diverse exposure pattern across participating sites. In multiple regression modelling, a positive association between markers of early dysglycemia and urinary zinc was found in both mothers and offspring after adjustment for common risk factors for diabetes. The analysis showed weaker, positive and negative associations of the 2-hour glucose value with urinary selenium and arsenic respectively. A positive association between 2-hour glucose values and cadmium was found only in mothers in the fully adjusted model when participants with established diabetes were excluded. There was a high degree of concordance between mother and offspring urinary metal profiles. Mother to offspring urinary metal ratios were unique for each metal, providing insights into changes in their homeostasis across the lifespan.

Significance:

Urinary levels of essential and non-essential metals are closely correlated between mothers and their offspring in an international cohort. Urinary levels of zinc, selenium, arsenic, and cadmium showed varying degrees of association with early dysglycemia in a comparatively healthy cohort with a low rate of preexisting diabetes.

Keywords: Child Exposure/ Health, Disease, Dietary Exposure, Metals, Health Studies, Environmental Monitoring, Endocrine Disruptors

Introduction:

The dietary supply of essential trace metals and environmental exposure to non-essential metals influence many aspects of human health. This applies to both children during development as well as to the adult population.1-4 Deficiency of essential trace metals such as selenium (Se), zinc (Zn), and molybdenum (Mo) results in adverse health effects.4-8 Several sequalae of exposure to excess levels of non-essential metals and metalloids with toxic potential are well described. These include deleterious effects associated with exposure to lead (Pb; neurotoxicity and cancer)2, 9, arsenic (As; cancer, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus-T2DM)2, 10-15, and cadmium (Cd; cancer, male hypofertility, nephrotoxicity, T2DM).2, 16-21 Some reports also provide evidence for adverse health outcomes in settings of excess supply of essential metals such as Se.22-24 This highlights the need for population data on the associations between exposure levels to individual metals and health outcomes in well characterized cohorts. An obstacle towards this goal is the confounding effect of common co-exposure patterns within geographically restricted cohorts.

Excretion of urinary elements is accepted as a good proxy for intake levels and/ or body content for most elements.2 In the present study, we report results from analyzing the elemental profiles in a subset of urine samples collected from ten international sites during the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow Up Study (HAPO-FUS). HAPO-FUS is an observational study that was conducted at ten international centers in mothers and their offspring. A main focus of HAPO-FUS was a detailed characterization of glycemic and anthropometric outcomes in mothers and their offspring.25 Samples collected included urine samples. Due the wide geographic distribution of the study sites, HAPO-FUS provides unique advantages in studying the relationship between nutritional and environmental exposure to essential and non-essential trace elements and glycemic outcomes across a diverse population with a wide variety of dietary habits and exposures, thereby mitigating the confounding effect of common metal co-exposure patterns common in geographically restricted cohorts. We sought to examine the relationship between essential and non-essential trace metal concentrations and glycemic outcomes in urine samples collected during HAPO-FUS. Our analysis of glycemic outcomes focused mainly on the essential and non-essential elements As, Zn, Se, and Cd as these have previously been associated with modifying effects on glycemic outcomes. 10-14, 20, 22-24, 26-35 Additionally, we examined the relationship between maternal and offspring urinary metal levels.

Materials and Methods:

Study population:

Details of the HAPO-FUS were previously published.25, 36, 37 Briefly, the HAPO-FUS was an observational study conducted in 10 international centers as a follow-on study to the original HAPO Study. It evaluated a subset of the HAPO Study cohort between 2013 and 2016. The original HAPO Study was a landmark international study conducted from 2000 to 2006 that enrolled 25,505 pregnant women in 15 international field centers and examined the association between the levels of maternal glucose below values diagnostic of overt diabetes and pregnancy outcomes.38 Women underwent a 75 gram, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test around gestational week 28. Women who exceeded predefined glucose thresholds were unblinded and excluded from the study (105 mg/dl fasting, 200 mg/dl at 2 hours post glucose load). HAPO-FUS was a follow up study performed in a subset of mothers and offspring from 10 of the 15 field centers in the original HAPO Study: Bangkok, Thailand; Barbados, West Indies; Belfast, UK; Bellflower, CA, USA; Chicago, IL, USA; Cleveland, OH, USA; Hong Kong, China; Manchester, UK; Petah-Tiqva, Israel; Toronto, Canada. Urine samples and measures of glycemia were obtained from 4322 mothers and 4145 offspring. Mother-offspring sample pairs were stored and labelled with a unique identifier for each pair. For the current study, a subset of sample pairs from each of the study sites was selected randomly by a person blinded to the data except for study center. In cases where only the mother or offspring sample was available for the selected sample-pair number, the available sample was analyzed without the corresponding missing sample.

Measurement of urinary metal concentrations:

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (ICP-MS) was performed to measure total content of selected elements in urine samples as previously described by us after adaptation of the procedure to urine samples in accordance with the CDC recommendations with modifications.39, 40 Briefly, urine samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. 500 μl of stored urine samples were used to determine concentrations of the following elements: zinc (66Zn), selenium (77Se), cobalt (59Co), molybdenum (95Mo), sodium (23Na), magnesium (24Mg), potassium (39K), and calcium (44Ca), as well as the non-essential elements arsenic (75As), mercury (202Hg), lead (208Pb), lithium (7Li), cadmium (111Cd), nickel (60Ni), tungsten (182W), thallium (205Tl), aluminum (27Al), iron (57Fe), copper (63Cu), manganese (55Mn), chromium (52Cr) and tin (118Sn). Samples were prepared for ICP-MS by adding 2% trace metal (TM) grade HCl (Fisher, Cat. # A508-4), 2% TM grade HNO3 (Fisher Optima, Cat. #A467-250), and supplemented with 0.01 μg/ml TM grade Gold HCl (MSAU-100PPML, Inorganic Ventures, VA) for stabilization of Mercury and diluted with TM grade water (EMD Millipore, Cat. #WX0003-6) to a final dilution of 1:4. ICP-MS was performed using an iCAP Q ICP-MS system (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Serially diluted standards between 0 and 90 ppb of a mixed element solution (inorganic ventures, Cat. # IV-ICPMS-71A&B) were used for calibration. Samples were measured in duplicates, and the average used for analysis. In case of a discrepancy of more than 25% between duplicates in one or more element, samples were prepared and analyzed again in duplicates and the average of the three closest values was used for analysis. In cases where the standard deviation between the three closest results was higher than 20%, the affected metal value from this sample was excluded entirely from analysis. Standardized urine samples containing standardized levels of the elements of interest were obtained from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and used for method validation in each run (NIST standards #2668 and #3668). Values for Al, Fe, Cu, Mn, and Cr were excluded from all analyses as results did not meet these quality control criteria on more than 10% of the samples.

Determination of urine creatinine concentrations:

Urine creatinine concentrations were measured in the clinical laboratory at Northwestern Memorial Hospital on a clinical laboratory platform (AU 5800, Beckman Instruments, Brea, CA) using the Beckman urinary creatinine kit OSR6678 (Jaffe procedure41) approved for use in clinical diagnostics by the US Food and Drug Administrations. Intra- and inter-day coefficients of variation (CV) are consistently less than 5 %. This laboratory conforms to FDA’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA).

Statistical Analysis:

Summary statistics included medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and tables of frequencies and counts for categorical variables. Absolute metal concentrations were used for analysis, as well as creatinine adjusted metal concentrations that were calculated by dividing absolute metal concentrations by creatinine levels. Heatmaps were developed for visual display of metal concentrations across field centers for both mothers and offspring; metal concentrations were standardized by subtracting the overall mean and dividing by the standard deviation for each metal and means of the standardized values were plotted on the heatmap for each field center. Heatmaps were also used for visual display of correlations between mother and offspring metal concentrations, with colors corresponding to the strength of the correlation.

Mixed effects multiple linear regression models were used to examine associations between metal concentrations. Models included a random intercept for field center. Urinary creatinine concentrations were included in all models to adjust for urine diluteness.42 In Model 1, fixed effects adjustments were included for creatinine concentration. In Model 2 for analyses of glucose and metal concentrations in mothers, fixed effects adjustments were included for creatinine concentration and maternal BMI, mean arterial pressure, height and smoking status at HAPO FUS. In Model 2 for analyses of glucose and metal concentrations in offspring, fixed effects adjustments were included for creatinine concentration and age, Tanner stage (categorical variable for Tanner stage groups 2/3 and 4/5 v. Tanner stage 1) and offspring BMI at HAPO FUS. These co-variates for model 2 in mothers and offspring were chosen based on previously published analyses in this dataset.37 The main analysis included all subjects. In some analyses, subjects with diabetes mellitus (either type) were excluded as some evidence suggests that changes in renal physiology in response to fully established diabetes may alter metal homeostasis and renal metal excretion.26, 43-49 Beta parameter estimates along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported from these mixed effects models. Model fit was evaluated by examining qq-plots and plots of residuals. Nominal p-values are reported without multiple comparisons adjustment. Generalized linear mixed-effects models with binary outcomes for impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose 100-125 mg/dL), impaired glucose tolerance (2-hr glucose 140-199 mg/dL), and prediabetes (impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance) were fit using the same covariates from maternal models 1 and 2 as described for continuous outcomes. Odds ratio estimates along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported from these generalized linear mixed-effects models. Model fit was evaluated with Hosmer Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test. For both linear and logistic regression models, restricted cubic splines were fit with the rms R package to confirm linearity for the primary metal predictors of interest. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.1.1).

Institutional approval.

The HAPO-FUS was approved by the institutional Review Board (IRB). This ancillary study was classified as exempt from requiring IRB approval by the institutional IRB and approved by the HAPO-FUS steering committee.

Results:

Cohort Characteristics:

Characteristics of the cohort are detailed in Table 1. Urine samples from a total of 1012 mothers and 1013 offspring from ten international field centers were analyzed. Of these, there were 968 matched mother-offspring pairs. The median age for mothers was 42.5 years (IQR 37.9-45.0) and 11.6 years (IQR 11.1-12.0) for offspring. Offspring age also represents the time between the end of the original HAPO observation period and the HAPO-FUS visit for the included subjects. In this sub-cohort, 36 mothers had been diagnosed with T2DM by the time of the HAPO FUS visit, while none were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). 2 offspring had been diagnosed with T2DM and one was diagnosed with T1DM. Median fasting, and 2-hour glucose values were 90.5 mg/dl (IQR 86.0 – 95.0) and 109.5 mg/dl (IQR 91.0-131.8) respectively in mothers and 90.0 mg/dl (IQR 85.0 - 94.0) and 108.0 (IQR 95.0 -121.0) in offspring.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the HAPO-FUS sub-cohort included in the analysis

| Mothers | Offspring | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1-Q3) | Count (%) | Missing n (%) | Median (Q1-Q3) | Count (%) | Missing n (%) | ||

| Total n | 1012 | 1013 | |||||

| Age (y) | 42.5 (37.9-45.9) | 15 (1.5%) | 11.6 (11.1-12.0) | 1 (0.1%) | |||

| BMI | 25.6 (22.5-30.0) | 19 (1.9%) | 18.5 (16.3-21.7) | 4 (0.4%) | |||

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 90.5 (86.0-95.0) | 44 (4.3%) | 90.0 (85.0-94.0) | 56 (5.5%) | |||

| 2-Hour Glucose (mg/dL) | 109.5 (91.0-131.8) | 64 (6.3%) | 108.0 (95.0-121.0) | 113 (12.3%) | |||

| Self Reported Ancestry | Asian | 113 (12.3%) | 0 (0%) | 243 (24%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Black | 147 (14.5%) | 153 (15.1%) | |||||

| Hispanic | 111 (11%) | 109 (10.8%) | |||||

| White | 508 (50.2%) | 495 (48.9%) | |||||

| Other | 14 (1.4%) | 13 (1.3%) | |||||

| Type 2 Diabetes History | 36 (3.6%) | 28 (2.8%) | 2 (0.2%) | 54 (5.3%) | |||

| Type 1 Diabetes History | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) | |||||

| Impaired Fasting Glucose at HAPO-FUS visit (fasting glucose 100-125 mg/dl) | 103 (10.2%) | 44 (4.3%) | 58 (%) | 56 (5.5%) | |||

| Impaired Glucose Tolerance at HAPO-FUS visit (2-Hour Glucose 140-199 mg/dl on OGTT | 148 (14.6%) | 64 (6.3%) | 72 (7.0%) | 113 (11.2%) | |||

| Composite of (IGF or IGT) | 216 (21.3%) | 65 (6.4%) | 118 (%) | 113 (11.2%) | |||

| Smoking Status | 69 (6.8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |||

Field Center Urinary Metal Profile Heterogeneity:

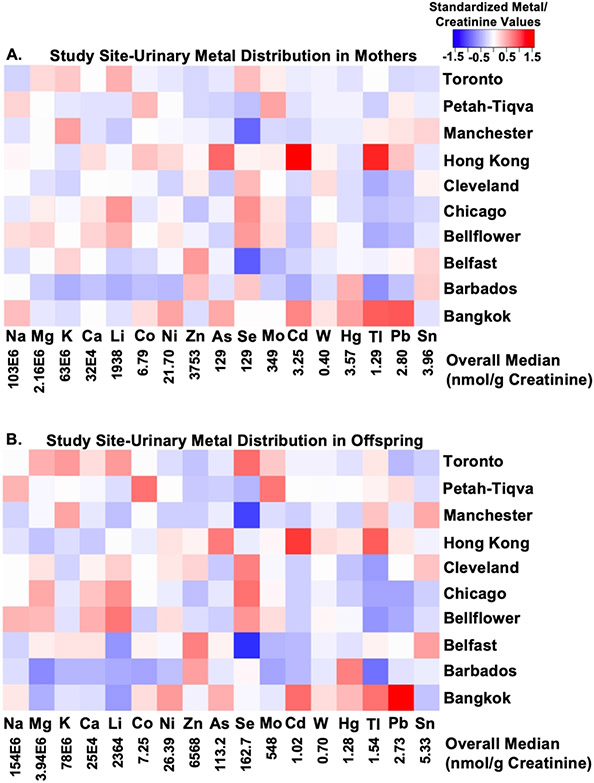

A marked heterogeneity of urinary levels of most elements examined was observed among samples from the 10 international field centers participating in the HAPO-FUS. A heat map of metal distributions illustrates the heterogeneity in the distribution of urinary metal levels across various sites (Fig. 1 for creatinine adjusted values, supplemental Fig. 1 for absolute metal concentrations). Absolute and creatinine corrected urinary metal values, as well as averages of mother to offspring elemental ratios across sites are provided in supplemental table 1. The exposure to the essential element Se and non-essential metals with toxic properties, Pb, Tl, Cd, As, and to a lesser degree Hg, showed marked heterogeneity. Values of note that may have clinical relevance include the high urinary levels of Pb (offspring median 7.05 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 5.21 to 10.84), Cd (mothers median 5.79 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 4.09 to 8.55), and As (mothers median 633 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 468 to 1015) in samples from Bangkok. Comparatively high levels of Cd (mothers median 8.67 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 6.15 to 12.39) and As (offspring median 793 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 413 to 1296) were found in Hong Kong. Comparatively low concentrations of Se were found in Belfast (mothers median 75 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 64 to 95, offspring 80 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 64 to 95), Manchester (mothers median 79 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 67 to 98, offspring 90 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 73 to 107), and Petah Tiqva (mothers median 108 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 90 to 122, offspring 140 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 115 to 160). Metal levels stratified by continent, ancestry and BMI category are provided in supplemental table 2. The analyses by continent and, ancestry largely reflected the results of the analysis by field center. High values for urinary As was found in persons of Asian ancestry (mothers median 588 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 362 to 1050, offspring 527 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 323 to 972) and in persons living in Asia (mothers median 494 nmol/g creatinine, IQR 171 to 918, offspring 409 nmol/g creatinine, IQR135 to 794). No overt differences in metal profiles were found between BMI groups in the BMI stratified analysis.

Figure 1:

Heatmap of the variation of creatinine corrected urine metal values across study sites for mothers (A) and offspring (B) (see supplemental Fig. 1 for heat map not adjusted for creatine and supplemental table 1 for numerical values). Concentrations were standardized for each metal.

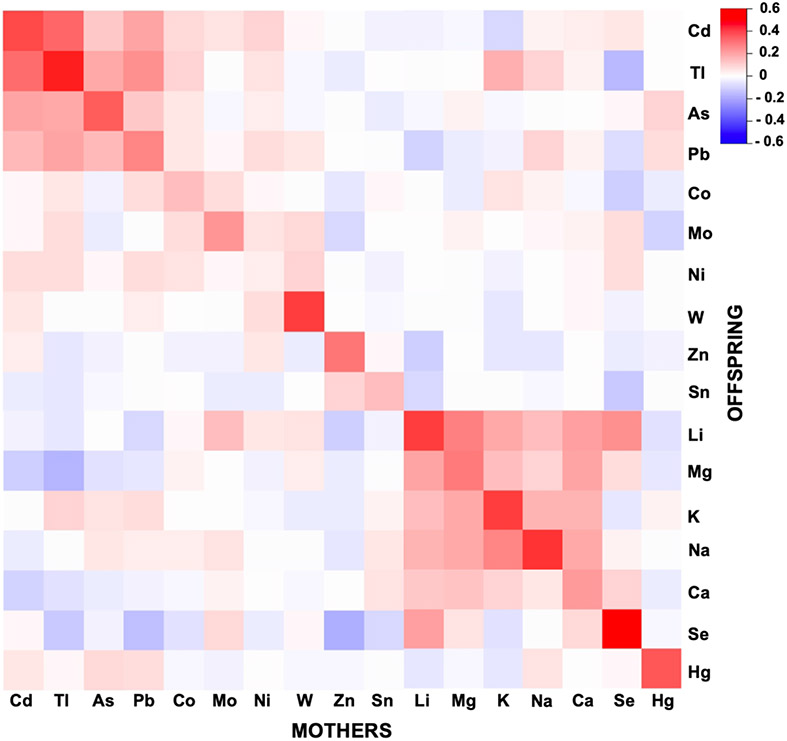

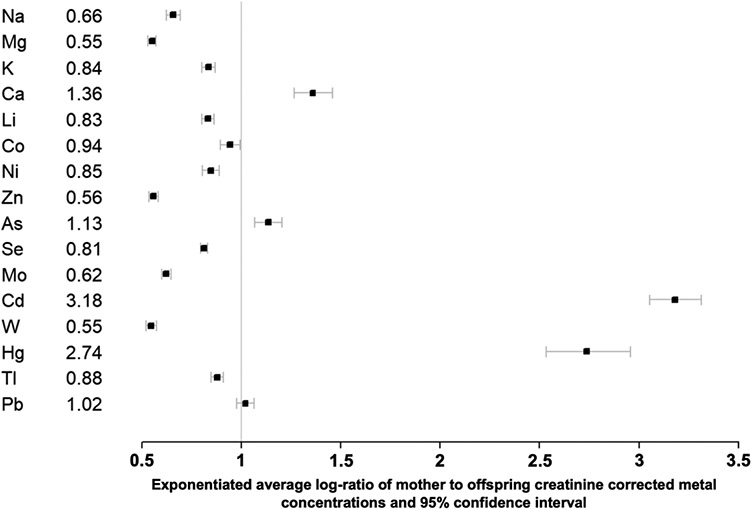

Relationship Between Mother and Offspring Urinary Metal Profiles

Positive (concordant) correlations between mother and offspring urinary concentrations of each of the elements examined were observed (Fig. 2). Of the essential and non-essential trace elements examined, the correlation was strongest for Tl, W, Hg, and Se. The weakest correlations were found for Ni and Co. In order to gain insights into differences in trace elemental handling between mothers and offspring, such as gradual accumulation and age-related differences in uptake and elimination, we examined the mother to offspring ratio for each element within each of the mother offspring pairs (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. 3 for creatinine adjusted and unadjusted values respectively). The study site specific median and IQR for these ratios can be found in supplemental table 1. The highest median mother to offspring ratios were for Cd (3.35 IQR 1.87 to 6.07) and Hg 2.86 (IQR 1.15 to 6.84).

Figure 2:

Heatmap of strength of correlations between mother and offspring creatinine corrected metal concentrations (see supp. Fig. 2 for correlations of non-creatinine corrected metal concentrations)

Figure 3:

Ratio of mother to offspring creatinine corrected urine metal concentration (values presented as exponentiated average log-ratio of mother to offspring creatinine corrected metal concentrations in urine and 95% confidence interval). Sn ratio not calculated due to below detection limit values in several samples (limit of detection 0.21 nmol/L).

Mixed effects multiple linear regression modeling of the relationship between 2-hour glucose values and urinary metal profile:

We performed mixed effects multiple linear regression modeling to examine the relationship between urinary levels of As, Zn, Se, and Cd (independent variables) and the 2-hour glucose values from the 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (GTT) during the HAPO-FUS visit (dependent variable). Results are summarized in Table 2A. An unadjusted analysis (model 1, adjusted only for creatinine) and an analysis adjusted for parameters known to influence the risk for dysglycemia (model 2) were conducted separately in mothers and their offspring to examine the association between urinary metal levels and 2-hr glucose levels (Table 2A). Urinary Zn levels were positively associated with the 2-hour glucose value in the fully adjusted model 2 in both mothers and offspring (Table 2A sections I and III, parameter estimates 6.03 (95% CI 2.88 to 9.19) and 2.49 (95% CI 0.16 to 4.81), respectively). In the unadjusted model 1, Zn was positively associated with the 2-hour glucose value in mothers (parameter estimate 8.09, 95% CI 4.87 to 11.32). As was negatively associated with 2-hour glucose values only in mothers in both model 1 and 2 (parameter estimates −3.00, 95% CI −5.37 to - 0.64 and −2.36, 95% CI −4.64 to −0.08 respectively). Se was positively associated with the 2-hour glucose value in mothers in both model 1 and 2 (parameter estimates 5.25, 95% CI 1.14 to 9.37 and 4.37, 95% CI 0.41 to 8.32). An additional analysis that excluded persons with diabetes mellitus was conducted. For this analysis, 22 and 20 mothers were excluded in model 1 and 2 respectively and 1 offspring was excluded. The associations in offspring did not change in this analysis (results not shown). In mothers (Table 2A section II), the following associations with the 2-hour glucose value were found after excluding subjects with diabetes: In the unadjusted model 1, a positive association with Zn (parameter estimate 3.53, 95% CI 0.90 to 6.16), and a negative association with As (parameter estimate −2.37, 95 % CI −4.23 to 0.05). In the adjusted model 2, a negative association with As (parameter estimate −1.84, 95% CI −3.65 to −0.04) and a positive association with Cd (parameter estimate 2.42, 95% CI 0.15 to 4.70) were found.

Table 2A:

Regression analysis with OGTT 2-hour glucose value as continuous outcome variable. I: Mothers, II: Mothers after exclusion of participants diagnosed with DM (either type), III: Offspring

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I: Mothers, all participants | Predictors | Estimates | 95% CI | P | Estimates | 95% CI | P |

| Creatinine | −0.09 | −0.14 to −0.04 | 0.001 | −0.07 | −0.12 to −0.02 | 0.005 | |

| Urinary Zn | 8.09 | 4.87 to 11.32 | <0.001 | 6.03 | 2.88 to 9.19 | <0.001 | |

| Urinary As | −3.00 | −5.37 to −0.64 | 0.013 | −2.36 | −4.64 to −0.08 | 0.042 | |

| Urinary Se | 5.25 | 1.14 to 9.37 | 0.012 | 4.37 | 0.41 to 8.32 | 0.031 | |

| Urinary Cd | 0.67 | −2.25 to 3.59 | 0.654 | 1.30 | −1.55 to 4.14 | 0.371 | |

| II: Mothers, subjects with DM excluded | Creatinine | −0.04 | −0.08 to 0.00 | 0.054 | −0.03 | −0.07 to 0.01 | 0.125 |

| Urinary Zn | 3.53 | 0.90 to 6.16 | 0.008 | 2.07 | −0.50 to 4.65 | 0.115 | |

| Urinary As | −2.37 | −4.23 to −0.50 | 0.013 | −1.84 | −3.65 to −0.04 | 0.046 | |

| Urinary Se | 2.85 | −0.44 to 6.14 | 0.089 | 2.42 | −0.72 to 5.56 | 0.131 | |

| Urinary Cd | 1.83 | −0.52 to 4.17 | 0.126 | 2.42 | 0.15 to 4.70 | 0.037 | |

| III: Offspring | Creatinine | −0.02 | −0.06 to 0.02 | 0.313 | −0.04 | −0.09 to −0.00 | 0.041 |

| Urinary Zn | 1.84 | −0.26 to 3.94 | 0.085 | 2.49 | 0.16 to 4.81 | 0.036 | |

| Urinary As | 0.45 | −0.88 to 1.77 | 0.508 | 2.08 | −0.45 to 4.60 | 0.107 | |

| Urinary Se | 1.13 | −1.08 to 3.34 | 0.316 | 1.43 | −1.07 to 3.92 | 0.262 | |

| Urinary Cd | −0.83 | −2.45 to 0.79 | 0.317 | −0.13 | −1.79 to 1.52 | 0.873 | |

Model 1 represents the unadjusted model except for creatinine to adjust for sample diluteness.

Model 2 was adjusted for BMI, mean arterial pressure, height, smoking status during HAPO-FUS (mothers) and BMI, age, tanner stage (offspring)

Analyses of Pb, Mo, W, and Hg showed a trend to an association between 2-hour glucose values and urinary Mo in the adjusted model 2 (parameter estimate 2.59, 95% CI −0.24 to 5.43) when all participants were included, but not after exclusion of participants with DM (supplemental table 3). No other association of any of these metals with 2-hour glucose values was found.

Generalized mixed effects regression modeling of the relationship between markers of early dysglycemia and urinary Cd, Zn, As, and Se in mothers:

Results from a mixed-effects models with binary outcomes in mothers for the odds ratio (OR) of impaired fasting glucose (IFG, fasting glucose 100-125 mg/dl mg/dl), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT, 2 hour glucose during OGTT 140-199 mg/dl), or a composite outcome of both (prediabetes) in separate models are shown in Table 2B. Subjects with diabetes were excluded from this analysis. In this analysis, Zn and Cd were associated with IFG risk in the unadjusted model I (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.84 and 1.25, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.52 respectively). In the adjusted model 2, IFG risk was associated with urinary Cd (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.69) and there was a trend towards an association with Zn (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.63). IGT risk was associated with urinary Zn in the unadjusted model 1 (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.66) and there was a trend to an association with Se (OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.69). In the adjusted model, there was a trend towards an association with Zn (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.57). Prediabetes risk was associated with urinary Zn (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.73) and there was a trend towards a negative association with urinary As (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.04) in the unadjusted model 1. In the fully adjusted model 2, there was an association between prediabetes risk and urinary Zn (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.58) and a trend towards an association with Cd (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.42). The number of offspring meeting criteria for IFG or IGT was too low to conduct a meaningful analysis.

Table 2B:

Regression analysis with early dysglycemia markers in mothers as binary outcome variable: I: Impaired fasting glucose (IFG), II: Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and III: The combined outcome of prediabetes defined as either impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. Participants with DM were excluded

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I: Impaired fasting glucose | Predictors | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

| Creatinine | 0.63 | 0.39 to 1.02 | 0.061 | 0.63 | 0.38 to 1.03 | 0.063 | |

| Urinary Zn | 1.41 | 1.09 to 1.84 | 0.010 | 1.24 | 0.94 to 1.63 | 0.134 | |

| Urinary As | 0.85 | 0.62 to 1.18 | 0.344 | 0.95 | 0.70 to 1.28 | 0.731 | |

| Urinary Se | 1.02 | 0.74 to 1.42 | 0.892 | 1.00 | 0.71 to 1.40 | 0.995 | |

| Urinary Cd | 1.25 | 1.02 to 1.52 | 0.031 | 1.37 | 1.11 to 1.69 | 0.004 | |

| II: Impaired glucose tolerance | Creatinine | 0.67 | 0.44 to 1.01 | 0.054 | 0.71 | 0.47 to 1.07 | 0.104 |

| Urinary Zn | 1.32 | 1.05 to 1.66 | 0.019 | 1.24 | 0.98 to 1.57 | 0.078 | |

| Urinary As | 0.83 | 0.62 to 1.11 | 0.210 | 0.87 | 0.66 to 1.15 | 0.334 | |

| Urinary Se | 1.27 | 0.96 to 1.69 | 0.096 | 1.21 | 0.91 to 1.59 | 0.187 | |

| Urinary Cd | 1.11 | 0.92 to 1.34 | 0.274 | 1.15 | 0.95 to 1.39 | 0.158 | |

| III: Prediabetes (IFG or IPG) | Creatinine | 0.65 | 0.46 to 0.92 | 0.015 | 0.66 | 0.46 to 0.95 | 0.023 |

| Urinary Zn | 1.41 | 1.14 to 1.73 | 0.001 | 1.28 | 1.03 to 1.58 | 0.025 | |

| Urinary As | 0.80 | 0.61 to 1.04 | 0.089 | 0.86 | 0.66 to 1.11 | 0.232 | |

| Urinary Se | 1.13 | 0.89 to 1.44 | 0.296 | 1.11 | 0.87 to 1.42 | 0.398 | |

| Urinary Cd | 1.13 | 0.95 to 1.34 | 0.171 | 1.19 | 0.99 to 1.42 | 0.061 | |

Model 1 represents the unadjusted model except for creatinine to adjust for sample diluteness.

Model 2 was adjusted for BMI, mean arterial pressure, height, smoking status during HAPO-FUS

Discussion:

Herein we report findings from a subset of participants from the international HAPO - FUS cohort in which we examined the urinary concentration of 18 essential and non-essential elements as a reflection of exposure patterns in mother-offspring pairs from ten international sites across three continents. These novel data provide unique insights into the concentration, mother-offspring correlation, and association with glucose tolerance of a subset of elements in this diverse cohort.

Mixed effect multiple regression modelling that included analyses in participants without diabetes provides important new evidence for associations between 2-hour glucose values – a proxy for early dysglycemia – and urinary Zn, As, Se, and Cd. The validity of the results from this analysis is strengthened by the variation in exposure patterns across the study sites. This provides a unique advantage towards mitigating the effect of common metal co-exposure patterns when analyzing associations between exposure patterns to specific elements in isolation. Due to the HAPO-FUS study design, we can both adjust for field center and jointly model the observed metal levels to rigorously assess independent associations of individual metals with the outcomes of interest.

Our analysis of the distribution of essential and non-essential trace metals showed a heterogenous exposure pattern across the ten international centers participating in the HAPO-FUS. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report direct human exposure data across these geographic areas in a single study. Prior cross-regional comparison data were mostly compiled from individual, geographically limited studies, from environmental/ nutritional studies, or from dietary estimates.50, 51 As previously reported by others and confirmed by our current data, these metal co-exposure patterns are often unique to defined geographic areas owing to unique environmental and nutritional conditions.52-55

Our multiple regression analysis defined 2-hour glucose values during oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) as the outcome variable and the essential metals Se and Zn and the non-essential metals with toxic properties, As and Cd, as independent variables. These metals were selected due to previous evidence of an associations of each of these metals with changes in glucose homeostasis and risk for diabetes.10-14, 20, 22-24, 26-35 The OGTT 2-hour glucose value was chosen as it is a sensitive marker for early stages of dysglycemia.56, 57

We found that zinc was positively associated with the 2-hour OGTT glucose value in mothers in both the fully adjusted and a minimally adjusted model that included only urinary creatinine, Zn, Se, As, and Cd as independent variables. In the offspring, this association was present only in the fully adjusted model. Consistent with this, Zn was also associated with an increased odds ratio of IFG, IGT, and the composite outcome of prediabetes in the unadjusted model as well as with prediabetes in the adjusted model in mothers. This provides added confidence that the association of urinary Zn with glucose values holds true for glucose values in the prediabetes range and is not limited to values below the prediabetes threshold. Prior reports suggest a complex relationship between Zn intake, glucose homeostasis, and urinary Zn excretion. Fenandez-Cao et al reported a meta-analysis that showed an association of higher blood Zn levels with increased T2DM risk.44 On the other hand, other investigators reported lower blood zinc levels in patients with fully established diabetes mellitus.27-29 Similarly, Shan et al in a case control study found an inverse association between plasma Zn concentrations and risk for T2DM.58 El-Yazigi et al reported higher urinary Zn concentrations in participants with established T2DM.26 This increase in urinary Zn concentration together with lower serum Zn concentration (in most but not all prior studies) is commonly interpreted as an increase in urinary excretion related to changes in renal physiology secondary to T2DM.26, 43-49 Galvez-Fernandez et al reported higher urinary Zn at baseline to be associated with higher risk for developing dysglycemia in the future.59 They propose that this is due to elevated renal Zn excretion in persons at risk for dysglycemia rather than higher Zn intake being associated with dysglycemia risk. However, our observation of an association between higher urinary Zn and early markers of disturbed glucose homeostasis, including in participants with only early subtle dysglycemic changes below the threshold of diabetes mellitus (minimally adjusted model) and in healthy, young offspring without diabetes likely points to a true association between higher body Zn content and/ or higher Zn intake and an increase in risk for early dysglycemia. Although Zn is an essential metal for virtually all eucaryotic cells, it is possible that the current Zn supply could result in Zn excess in susceptible cells. Insulin producing ß-cells with their well described high Zn turnover may be especially vulnerable in this regard. Indeed, a rare, naturally occurring loss of function mutation in the ß-cell Zn transporter ZnT8 that is known to reduce the Zn concentration in ß-cells confers a protective effect against T2DM.60, 61 Similarly, a variant of ZnT8 that has been associated with an increased risk for T2DM increases the cellular concentration of Zn.40, 62 A deterioration in the function of insulin producing ß-cells in pancreatic islets of Langerhans -often in the setting of insulin resistance- is the fundamental cause of T2DM. In the early stages of development of T2DM, the decline in ß-cell function usually develops gradually over many years with only subtle changes in markers of glycemia, such as the 2-hour glucose value during an OGTT in early stages.56 Wider physiologic changes such as renal changes are typically not expected in these earlier stages. Only once a substantial portion of ß-cell insulin secretory capacity has been compromised does the full clinical picture of T2DM develop. Alternatively, it is plausible that a common factor may result in both altered glucose homeostasis and changes in Zn excretion patterns. Therefore, further research is required to further examine the underlying mechanism for the association between urinary Zn and early changes in glucose disposition.

A positive association between As exposure and the risk for T2DM is well established in cohorts exposed to high levels of As,11-14, 35, as well as in experimental models.10, 34, 63-65 However, it is unclear whether As exposure plays a relevant role at lower levels of exposure found in the general population. The lack of a positive association between As and 2-hour glucose values or odds ratio for prediabetes in our study supports the notion that lower levels of As exposure such as the ones found in our study population are not associated with dysglycemia. The negative association between early dysglycemia and As in mothers -although weak- may point to variable effects of As at different concentrations. It is also likely that differences in toxicity of various As species such as divalent and trivalent As, as well as inorganic and organic As species such as mono- and di-methyl arsenate contribute to varied associations between markers of As exposure and health outcomes.64, 66, 67 Measuring As species was beyond the scope of the current study. Given that we did not perform species analysis in our samples, no general inference can be made about the effects of all As compounds from our data. It is also possible that co-exposure with other metals other than the ones incorporated in our mixed effect model - Se, Zn, and Cd- contributed to our findings, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive analysis in sufficiently powered larger cohorts.

Growing evidence from others together with our studies point to a high sensitivity of insulin-producing ß-cells to Cd accumulation and toxicity, 40, 68-71 thereby raising concern about a potential causal relationship between exposure to Cd and T2DM. Our prior analysis of human insulin-producing pancreatic islets detected potentially relevant concentrations of Cd in human islets of Langerhans in the general US population.40 This was supported by our studies using a newly established mouse model for oral Cd exposure.71 Low-level chronic human Cd exposure in the general population below threshold levels generally considered toxic is highly prevalent.19, 31, 72-79 Once absorbed, the half-life of Cd in tissues is reported to range between 7 to 16 years.69, 75, 80-82 Several epidemiologic and experimental studies as well as a recent meta-analysis by Filippini et al provide evidence that chronic exposure to Cd is likely associated with an increased incidence of dysglycemia and T2DM.20, 21, 30-32 However, other epidemiologic studies showed no association between markers of Cd exposure and the prevalence of T2DM.83-86 One potential source of these discrepancies may relate to changes in renal physiology once T2DM is established, whereby the relationship between the excretion of solutes, including divalent metals, and exposure levels/ body burden is altered by dysglycemia in the diabetic range as well as varying insulin levels.26, 45-49, 87 Consistent with this, our analysis reported herein found a positive association between the 2-hour glucose values as well as odd ratio for impaired fasting glucose and urinary Cd levels in mothers after excluding participants with fully established diabetes. No association was found in offspring, a finding that is not surprising given that Cd levels in the offspring were much lower, consistent with the long half-life of Cd leading to its gradual accumulation over many years.

The positive association between Se and 2-hour glucose values in mothers is in line with prior reports. Although Se is known to be an essential metal, higher Se intake and blood levels have been associated with higher blood glucose levels, insulin resistance and T2DM risk in several studies.22-24, 33 It is unclear if this association is a true reflection of a deleterious effect of excess Se intake and what the threshold exposure level -if any- for this effect is. Our observation that this relationship is stronger in our mixed effect model when mothers with fully established DM are included raises the possibility that changes in Se homeostasis -especially renal excretion- as a result of early dysglycemia may be at least contributing to this observation. This highlights the need for more research to fully elucidate the mechanism and directionality of the observed relationship between Se and dysglycemia. As discussed earlier, changes in renal metal handling secondary to established diabetes mellitus have been described, though so far not for early dysglycemia.26, 43-49

Urinary Mo showed a weak trend to an association with 2-hour glucose in the adjusted model. Menke et al have previously reported higher levels of Mo in people with DM.83 Given that the observed trend disappeared in our cohort after exclusion of participants with overt DM, it is likely that any association between urinary Mo is only present in more advanced stages of dysglycemia.

The relatively high level of As in participants from Hong Kong is somewhat surprising given that Wong et al reported a relatively low average daily intake of 0.22 ug/kg body weight -though the Wong et al study was limited to examining inorganic arsenic.88 Consistent with our report, dietary Se supply varies widely across the globe.89, 90 Low Se in Ireland and the United Kingdom has been reported based on data obtained in the 1990s and early 2000s, which led to recommendations for improving dietary Se intake.91-93 Our data suggest that comparatively low nutritional Se intake persisted until the timepoint of HAPO-FUS sample collection in some areas. Although Se deficiency cannot be implied from our urinary Se concentrations, comparatively low concentrations were found in several study sites. Specifically, in our cohort, the lowest Se concentrations were found in participants from Belfast, Manchester, and Petah Tiqva.

Our results indicate a high concordance between mother and offspring urinary metal concentrations. It is likely that most of this concordance is due to common exposure patterns within the household. It is possible that common genetic determinants of metal absorption, handling, and excretion may be an additional contributing factor. Genetic polymorphisms have been reported to modify Zn, Cd, Pb, Hg, and Se homeostasis.94, 95

The ratio of mother to offspring urine metal values reported herein is expected to provide useful insights into changes in the homeostasis of various elements. The relatively high ratio of mother to offspring urinary Ca is likely due to the higher utilization of Ca by offspring for bone growth given that all the offspring in our cohort were at an age where bone growth is expected. The high ratio of mother to offspring of Cd, Hg, and to a lesser extent As is consistent with prior reports of these toxic metals showing a pattern of gradual tissue accumulation over time, leading to a gradual rise in tissue levels of these metals. Therefore, the higher urinary levels of these elements in mothers compared to the offspring are not surprising as urinary levels of Cd, As, and Hg have been shown to be a good reflection of body burden for each of these elements.2 The ratio of mother to offspring urinary Pb is close to 1, given that urinary Pb -contrary to Cd, As, and Hg- reflects current intake status2, which is likely similar in mothers and offspring living in the same household.

In summary, our data provide novel evidence for a strong correlation between mother and offspring urinary metal patterns with a mother to offspring ratio that is unique for each metal. The study also provides new evidence for a strong positive association between early dysglycemia and urinary Zn, both in mothers and offspring. Weaker positive associations with urinary Se and Cd and negative associations with As were also found. Most of these associations persisted after excluding participants with established diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Impact Statement:

Our data provides novel evidence for a strong correlation between mother and offspring urinary metal patterns with a unique mother to offspring ratio for each metal. The study also provides new evidence for a strong positive association between early dysglycemia and urinary zinc, both in mothers and offspring. Weaker positive associations with urinary selenium and cadmium and negative associations with arsenic were also found. The low rate of preexisting diabetes in this population provides the unique advantage of minimizing the confounding effect of preexisting, diabetes related renal changes that would alter the relationship between dysglycemia and renal metal excretion.

Acknowledgements

ICP-MS metal analysis was performed at Quantitative Bio-elemental Imaging Center, Northwestern University that is supported by NASA Ames Research Center (NNA04CC36G).

Data and urine samples used in this ancillary study originated from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow Up Study (HAPO-FUS).

Funding

The HAPO Follow-up Study was funded by grant 1U01DK094830 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The HAPO Follow-up Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. REDCap is supported at Feinberg School of Medicine by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute. The research reported in this article was supported, in part by grant UL1TR001422 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. This ancillary study was also partially supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (5R01ES027011) awarded to MEM.

Consortium information:

Group Information: The collaborator members of the HAPO Follow-up Study Cooperative Research Group by field center are: Bangkok, Thailand: C. Deerochanawong, T. Tanaphonpoonsuk (Rajavithi Hospital) and S. Binratkaew, U. Chotigeat, W. Manyam (Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health); Barbados: M. Forde, A. Greenidge, K. Neblett, P. M. Lashley, D. Walcott (Queen Elizabeth Hospital, School of Clinical Medicine and Research, University of the West Indies); Belfast, Ireland: K. Corry, L. Francis, J. Irwin, A. Langan, D. R. McCance, M. Mousavi (Belfast Health and Social Care Trust) and I. S. Young (Queen’s University); Bellflower, California: J. Gutierrez, J. Jimenez, J. M. Lawrence, D. A. Sacks, H. S. Takhar, E. Tanton (Kaiser Permanente of Southern California); Chicago, Illiniois: W. J. Brickman, J. Howard, J. L. Josefson, L. Miller (Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine); Cleveland, Ohio: J. Bjaloncik, P. M. Catalano, A. Davis, K. Koontz, L. Presley, S. Smith, A. Tyhulski (MetroHealth Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University); Hong Kong, China: A. Li, R. C. Ma, R. Ozaki, W. H. Tam, M. Wong, C. Yuen (Chinese University of Hong Kong and Prince of Wales Hospital); Manchester, England: P. E. Clayton, A. Khan, A. Vyas (Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Healthy Sciences Centre and School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine, and Health, University of Manchester) and M. Maresh (St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre); Petah-Tikva, Israel: H. Benzaquen, N. Glickman, A. Hamou, O. Hermon, O. Horesh, Y. Keren, S. Shalitin (Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel) and Y. Lebenthal (Jesse Z. and Sara Lea Shafer Institute for Endocrinology and Diabetes, National Center for Childhood Diabetes, Schneider Children’s Medical Center of Israel, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University); and Toronto, Ontario, Canada: K. Cordeiro, J. Hamilton, H. Y. Nguyen, S. Steele (Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto). Coordinating Center: Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine (F. Chen, A. R. Dyer, W. Huang, A. Kuang, M. Jimenez, L. P. Lowe, W. L. Lowe Jr, B. E. Metzger, M. Nodzenski, A. Reisetter, D. Scholtens, O. Talbot, P. Yim). Consultants: D. Dunger, A. Thomas. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: M. Horlick, B. Linder, A. Unalp-Arida. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: G. Grave.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval:

HAPO-FUS was approved by the institutional Review Board (IRB). This ancillary study was classified as exempt from requiring IRB approval by the institutional IRB and approved by the HAPO-FUS steering committee.

Data availability statement:

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

References:

- 1.Klaassen CD, Watkins JB, Casarett LJ. Casarett & Doull's essentials of toxicology. McGraw-Hill Medical: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordberg G, Fowler BA, Nordberg M. Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attar T A mini-review on importance and role of trace elements in the human organism. Chemical Review and Letters 2020; 3: 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogden JD, Klevay LM. Clinical Nutrition of the Essential Trace Elements and Minerals. Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuttall JR, Supasai S, Kha J, Vaeth BM, Mackenzie GG, Adamo AM et al. Gestational marginal zinc deficiency impaired fetal neural progenitor cell proliferation by disrupting the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2015; 26: 1116–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aimo L, Mackenzie GG, Keenan AH, Oteiza PI Gestational zinc deficiency affects the regulation of transcription factors AP-1, NF-kappaB and NFAT in fetal brain. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2010; 21: 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modzelewska D, Sole-Navais P, Brantsaeter AL, Flatley C, Elfvin A, Meltzer HM et al. Maternal Dietary Selenium Intake during Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes in the Norwegian Mother, Father, and Child Cohort Study. Nutrients 2021; 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendel RR, Kruse T Cell biology of molybdenum in plants and humans. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1823: 1568–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellinger DC Lead neurotoxicity and socioeconomic status: conceptual and analytical issues. Neurotoxicology 2008; 29: 828–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S, Guo X, Wu B, Yu H, Zhang X, Li M Arsenic induces diabetic effects through beta-cell dysfunction and increased gluconeogenesis in mice. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maull EA, Ahsan H, Edwards J, Longnecker MP, Navas-Acien A, Pi J et al. Evaluation of the association between arsenic and diabetes: a National Toxicology Program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 1658–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin E, Gonzalez-Horta C, Rager J, Bailey KA, Sanchez-Ramirez B, Ballinas-Casarrubias L et al. Metabolomic Characteristics of Arsenic-Associated Diabetes in a Prospective Cohort in Chihuahua, Mexico. Toxicol Sci 2015; doi 10.1093/toxsci/kfu318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brauner EV, Nordsborg RB, Andersen ZJ, Tjonneland A, Loft S, Raaschou-Nielsen O Long-term exposure to low-level arsenic in drinking water and diabetes incidence: a prospective study of the diet, cancer and health cohort. Environ Health Perspect 2014; 122: 1059–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davila-Esqueda ME, Morales JM, Jimenez-Capdeville ME, De la Cruz E, Falcon-Escobedo R, Chi-Ahumada E et al. Low-level subchronic arsenic exposure from prenatal developmental stages to adult life results in an impaired glucose homeostasis. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association 2011; 119: 613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James KA, Byers T, Hokanson JE, Meliker JR, Zerbe GO, Marshall JA Association between lifetime exposure to inorganic arsenic in drinking water and coronary heart disease in Colorado residents. Environ Health Perspect 2015; 123: 128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saintilnord WN, Tenlep SYN, Preston JD, Duregon E, DeRouchey JE, Unrine JM et al. Chronic Exposure to Cadmium Induces Differential Methylation in Mice Spermatozoa. Toxicol Sci 2021; 180: 262–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchet JP, Lauwerys R, Roels H, Bernard A, Bruaux P, Claeys F et al. Renal effects of cadmium body burden of the general population. Lancet 1990; 336: 699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buha A, Dukic-Cosic D, Curcic M, Bulat Z, Antonijevic B, Moulis JM et al. Emerging Links between Cadmium Exposure and Insulin Resistance: Human, Animal, and Cell Study Data. Toxics 2020; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benoff S, Hauser R, Marmar JL, Hurley IR, Napolitano B, Centola GM Cadmium concentrations in blood and seminal plasma: correlations with sperm number and motility in three male populations (infertility patients, artificial insemination donors, and unselected volunteers). Mol Med 2009; 15: 248–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallia A, Allen NB, Badon S, El Muayed M Association between urinary cadmium levels and prediabetes in the NHANES 2005-2010 population. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2014; 37: 2960–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filippini T, Wise LA, Vinceti M Cadmium exposure and risk of diabetes and prediabetes: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Environ Int 2022; 158: 106920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardoso BR, Braat S, Graham RM Selenium Status Is Associated With Insulin Resistance Markers in Adults: Findings From the 2013 to 2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Front Nutr 2021; 8: 696024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohler LN, Foote J, Kelley CP, Florea A, Shelly C, Chow HS et al. Selenium and Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu CW, Chang HH, Yang KC, Kuo CS, Lee LT, Huang KC High serum selenium levels are associated with increased risk for diabetes mellitus independent of central obesity and insulin resistance. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2016; 4: e000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scholtens DM, Kuang A, Lowe LP, Hamilton J, Lawrence JM, Lebenthal Y et al. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow-up Study (HAPO FUS): Maternal Glycemia and Childhood Glucose Metabolism. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: 381–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.el-Yazigi A, Hannan N, Raines DA Effect of diabetic state and related disorders on the urinary excretion of magnesium and zinc in patients. Diabetes research 1993; 22: 67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garg VK, Gupta R, Goyal RK Hypozincemia in diabetes mellitus. J Assoc Physicians India 1994; 42: 720–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basaki M, Saeb M, Nazifi S, Shamsaei HA Zinc, copper, iron, and chromium concentrations in young patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Trace Elem Res 2012; 148: 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen J, Rosenkranz E, Overbeck S, Warmuth S, Mocchegiani E, Giacconi R et al. Disturbed zinc homeostasis in diabetic patients by in vitro and in vivo analysis of insulinomimetic activity of zinc. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2012; 23: 1458–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz GG, Il'yasova D, Ivanova A Urinary cadmium, impaired fasting glucose, and diabetes in the NHANES III. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 468–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Afridi HI, Kazi TG, Kazi N, Jamali MK, Arain MB, Jalbani N et al. Evaluation of status of toxic metals in biological samples of diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008; 80: 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swaddiwudhipong W, Limpatanachote P, Mahasakpan P, Krintratun S, Punta B, Funkhiew T Progress in cadmium-related health effects in persons with high environmental exposure in northwestern Thailand: a five-year follow-up. Environ Res 2012; 112: 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei J, Zeng C, Gong QY, Yang HB, Li XX, Lei GH et al. The association between dietary selenium intake and diabetes: a cross-sectional study among middle-aged and older adults. Nutr J 2015; 14: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu J, Woods CG, Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Zhang Q, Wong V, Collins S et al. Low-level arsenic impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells: involvement of cellular adaptive response to oxidative stress. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 864–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung TC, Huang JW, Guo HR Association between Arsenic Exposure and Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 368087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowe WL Jr., Scholtens DM, Kuang A, Linder B, Lawrence JM, Lebenthal Y et al. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow-up Study (HAPO FUS): Maternal Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Childhood Glucose Metabolism. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: 372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowe WL Jr., Scholtens DM, Lowe LP, Kuang A, Nodzenski M, Talbot O et al. Association of Gestational Diabetes With Maternal Disorders of Glucose Metabolism and Childhood Adiposity. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2018; 320: 1005–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Group HSCR, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1991–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2012 Survey Content Brochure. In, 2012.

- 40.Wong WP, Allen NB, Meyers MS, Link EO, Zhang X, MacRenaris KW et al. Exploring the Association Between Demographics, SLC30A8 Genotype, and Human Islet Content of Zinc, Cadmium, Copper, Iron, Manganese and Nickel. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peake M, Whiting M Measurement of serum creatinine--current status and future goals. Clin Biochem Rev 2006; 27: 173–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barr DB, Wilder LC, Caudill SP, Gonzalez AJ, Needham LL, Pirkle JL Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113: 192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chabosseau P, Rutter GA Zinc and diabetes. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016; 611: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez-Cao JC, Warthon-Medina M, V HM, Arija V, Doepking C, Serra-Majem L et al. Zinc Intake and Status and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau AL, Failla ML Urinary excretion of zinc, copper and iron in the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. J Nutr 1984; 114: 224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stenvinkel P, Bolinder J, Alvestrand A Effects of insulin on renal haemodynamics and the proximal and distal tubular sodium handling in healthy subjects. Diabetologia 1992; 35: 1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raz I, Havivi E Influence of chronic diabetes on tissue and blood cells status of zinc, copper, and chromium in the rat. Diabetes research 1988; 7: 19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward DT, Hamilton K, Burnand R, Smith CP, Tomlinson DR, Riccardi D Altered expression of iron transport proteins in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat kidney. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005; 1740: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinlaw WB, Levine AS, Morley JE, Silvis SE, McClain CJ Abnormal zinc metabolism in type II diabetes mellitus. The American journal of medicine 1983; 75: 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.In: Global Mercury Assessment 2018. United Nations Environment Program, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers AA, Murray CJL. Comparative quantification of health risks, volume 1: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. In. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Mukherjee B, Batterman S, Harlow SD, Park SK Urinary metals and metal mixtures in midlife women: The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Int J Hyg Environ Health 2019; 222: 778–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.OCED Environment Health and Safety Division ED. Considerations for Assessing the Risks of Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals, Series on Testing and Assessment No. 296. OECD, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Villarino M, Signes-Pastor AJ, Karagas MR, Riano-Galan I, Rodriguez-Dehli C, Grimalt JO et al. Exposure to metal mixture and growth indicators at 4-5 years. A study in the INMA-Asturias cohort. Environ Res 2022; 204: 112375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koszewicz M, Markowska K, Waliszewska-Prosol M, Poreba R, Gac P, Szymanska-Chabowska A et al. The impact of chronic co-exposure to different heavy metals on small fibers of peripheral nerves. A study of metal industry workers. J Occup Med Toxicol 2021; 16: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.LeRoith D, Taylor S, Olefsky J. Diabetes Mellitus, A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noctor E, Crowe C, Carmody LA, Saunders JA, Kirwan B, O'Dea A et al. Abnormal glucose tolerance post-gestational diabetes mellitus as defined by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies 2016; 175: 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shan Z, Bao W, Zhang Y, Rong Y, Wang X, Jin Y et al. Interactions between zinc transporter-8 gene (SLC30A8) and plasma zinc concentrations for impaired glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2014; 63: 1796–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galvez-Fernandez M, Powers M, Grau-Perez M, Domingo-Relloso A, Lolacono N, Goessler W et al. Urinary Zinc and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: Prospective Evidence From the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2022; e-pub ahead of print 2022/09/23; doi 10.2337/dc22-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dwivedi OP, Lehtovirta M, Hastoy B, Chandra V, Krentz NAJ, Kleiner S et al. Loss of ZnT8 function protects against diabetes by enhanced insulin secretion. Nat Genet 2019; 51: 1596–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Flannick J, Thorleifsson G, Beer NL, Jacobs SB, Grarup N, Burtt NP et al. Loss-of-function mutations in SLC30A8 protect against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2014; 46: 357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merriman C, Huang Q, Rutter GA, Fu D Lipid-tuned Zinc Transport Activity of Human ZnT8 Protein Correlates with Risk for Type-2 Diabetes. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 26950–26957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beck R, Chandi M, Kanke M, Styblo M, Sethupathy P Arsenic is more potent than cadmium or manganese in disrupting the INS-1 beta cell microRNA landscape. Arch Toxicol 2019; 93: 3099–3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li YY, Douillet C, Huang M, Beck R, Sumner SJ, Styblo M Exposure to inorganic arsenic and its methylated metabolites alters metabolomics profiles in INS-1 832/13 insulinoma cells and isolated pancreatic islets. Arch Toxicol 2020; 94: 1955–1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang M, Douillet C, Styblo M Arsenite and its trivalent methylated metabolites inhibit glucose-stimulated calcium influx and insulin secretion in murine pancreatic islets. Arch Toxicol 2019; 93: 2525–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kitchin KT, Wallace K The role of protein binding of trivalent arsenicals in arsenic carcinogenesis and toxicity. J Inorg Biochem 2008; 102: 532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Styblo M, Venkatratnam A, Fry RC, Thomas DJ Origins, fate, and actions of methylated trivalent metabolites of inorganic arsenic: progress and prospects. Arch Toxicol 2021; 95: 1547–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Edwards JR, Prozialeck WC Cadmium, diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009; 238: 289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El Muayed M, Raja MR, Zhang X, Macrenaris KW, Bhatt S, Chen X et al. Accumulation of cadmium in insulin-producing beta cells. Islets 2012; 4: 405–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chang KC, Hsu CC, Liu SH, Su CC, Yen CC, Lee MJ et al. Cadmium Induces Apoptosis in Pancreatic beta-Cells through a Mitochondria-Dependent Pathway: The Role of Oxidative Stress-Mediated c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Activation. PLoS One 2013; 8: e54374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong WPS, Wang JC, Meyers MS, Wang NJ, Sponenburg RA, Allen NB et al. A novel chronic in vivo oral cadmium exposure-washout mouse model for studying cadmium toxicity and complex diabetogenic effects. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2022; 447: 116057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olsson IM, Bensryd I, Lundh T, Ottosson H, Skerfving S, Oskarsson A Cadmium in blood and urine--impact of sex, age, dietary intake, iron status, and former smoking--association of renal effects. Environ Health Perspect 2002; 110: 1185–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bulat ZP, Dukic-Cosic D, Dokic M, Bulat P, Matovic V Blood and urine cadmium and bioelements profile in nickel-cadmium battery workers in Serbia. Toxicol Ind Health 2009; 25: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Link B, Gabrio T, Piechotowski I, Zollner I, Schwenk M Baden-Wuerttemberg Environmental Health Survey (BW-EHS) from 1996 to 2003: toxic metals in blood and urine of children. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2007; 210: 357–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarup L, Rogenfelt A, Elinder CG, Nogawa K, Kjellstrom T Biological half-time of cadmium in the blood of workers after cessation of exposure. Scand J Work Environ Health 1983; 9: 327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dakeshita S, Kawai T, Uemura H, Hiyoshi M, Oguma E, Horiguchi H et al. Gene expression signatures in peripheral blood cells from Japanese women exposed to environmental cadmium. Toxicology 2009; 257: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ebert-McNeill A, Clark S, Miller J, Birdsall P, Chandar M, Wu L et al. Cadmium intake and systemic exposure in postmenopausal women and age-matched men who smoke cigarettes. Toxicol Sci 2012; 130: 191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ruiz P, Mumtaz M, Osterloh J, Fisher J, Fowler BA Interpreting NHANES biomonitoring data, cadmium. Toxicol Lett 2010; 198: 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ferraro PM, Costanzi S, Naticchia A, Sturniolo A, Gambaro G Low level exposure to cadmium increases the risk of chronic kidney disease: analysis of the NHANES 1999-2006. BMC public health 2010; 10: 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Amzal B, Julin B, Vahter M, Wolk A, Johanson G, Akesson A Population toxicokinetic modeling of cadmium for health risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect 2009; 117: 1293–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maret W, Moulis JM The bioinorganic chemistry of cadmium in the context of its toxicity. Metal ions in life sciences 2013; 11: 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Elinder CG, Lind B, Kjellstrom T, Linnman L, Friberg L Cadmium in kidney cortex, liver, and pancreas from Swedish autopsies. Estimation of biological half time in kidney cortex, considering calorie intake and smoking habits. Archives of environmental health 1976; 31: 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Menke A, Guallar E, Cowie CC Metals in Urine and Diabetes in U.S. Adults. Diabetes 2016; 65: 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moon SS Association of lead, mercury and cadmium with diabetes in the Korean population: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2009-2010. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association 2013; 30: e143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nie X, Wang N, Chen Y, Chen C, Han B, Zhu C et al. Blood cadmium in Chinese adults and its relationships with diabetes and obesity. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2016; 23: 18714–18723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu B, Feng W, Wang J, Li Y, Han X, Hu H et al. Association of urinary metals levels with type 2 diabetes risk in coke oven workers. Environmental pollution 2016; 210: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wong WP, Wallia A, Edwards JR, El Muayed M Comment on Menke et al. Metals in Urine and Diabetes in U.S. Adults. Diabetes 2016;65:164–171. Diabetes 2016; 65: e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wong WW, Chung SW, Chan BT, Ho YY, Xiao Y Dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic of the Hong Kong population: results of the first Hong Kong total diet study. Food Chem Toxicol 2013; 51: 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rayman MP Selenium and human health. Lancet 2012; 379: 1256–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johnson CC, Fordyce FM, Rayman MP Symposium on 'Geographical and geological influences on nutrition': Factors controlling the distribution of selenium in the environment and their impact on health and nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc 2010; 69: 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Murphy J, Cashman KD Selenium status of Irish adults: evidence of insufficiency. Ir J Med Sci 2002; 171: 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murphy J, Hannon EM, Kiely M, Flynn A, Cashman KD Selenium intakes in 18-64-y-old Irish adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002; 56: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rayman MP, Rayman MP The argument for increasing selenium intake. Proc Nutr Soc 2002; 61: 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whitfield JB, Dy V, McQuilty R, Zhu G, Heath AC, Montgomery GW et al. Genetic effects on toxic and essential elements in humans: arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, selenium, and zinc in erythrocytes. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 776–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.da Rocha TJ, Korb C, Schuch JB, Bamberg DP, de Andrade FM, Fiegenbaum M SLC30A3 and SEP15 gene polymorphisms influence the serum concentrations of zinc and selenium in mature adults. Nutr Res 2014; 34: 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.