Abstract

Objectives

The aims of the present longitudinal retrospective observational case series study were to investigate the survival and success rates of primary non-surgical endodontic therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients with at least one endodontically treated tooth (ETT), with 5 years of follow-up and in compliance with the recall programme of at least 1 time per year in a private practice setting, were recruited. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed considering (a) tooth extraction/survival and (b) endodontic success as the outcome variables. A regression analysis was performed to evaluate prognostic factors associated with tooth survival.

Results

Three hundred twelve patients and 598 teeth were included. The cumulative survival rates showed 97%, 81%, 76% and 68% after 10, 20, 30 and 37 years, respectively. The corresponding values for endodontic success were 93%, 85%, 81% and 81%, respectively.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated high longevity in symptomless function as well as high success rates of ETT. The most significant prognostic factors associated with tooth extraction were the presence of deep (> 6 mm) periodontal pockets, the presence of pre-operative apical radiolucency and the lack of occlusal protection (no use of a night guard).

Clinical relevance

The favourable long-term (> 30 years) prognosis of ETT must encourage clinicians to rely on primary root canal treatment when taking the decision regarding whether a tooth with pulpal and/or periapical diseases should be saved or be extracted and replaced with an implant.

Keywords: Primary root canal treatment, Endodontic treatment, Tooth survival, Endodontic success, Long term

Introduction

Endodontic treatment is a highly predictable therapy for preserving the natural dentition, with demonstrated high long-term survival and success rates [1]. However, the lack of consistency in defining success and failure after endodontic therapy has resulted in reported results with considerable heterogeneity [2]. When endodontic success has been based on either strict or loose criteria, the pooled success rates have ranged between 74.7% (95% CI: 69.8–79.5%), when using strict radiographic and clinical criteria, and 85.2% (95% CI: 82.2–88.3%), when using loose criteria. Similarly, analyses by meta-regression showed that the reported success rates were 10.5% lower when based on strict criteria, compared to the application of loose success criteria [3]. These differences in the appraisal of success or failure hampered an effective assessment of the efficacy of endodontic therapy, and due to this, current trends in endodontic research focus on reporting tooth survival as well as success rates. Tooth survival after root canal treatment (RCT) has been defined as the continued presence of the tooth in function, provided it is symptom-less [4]. Using this definition, a systematic review based on randomised clinical trials reported that the pooled probability of long-term (4–5 and 8–10 years) tooth survival after RCT ranged between 93 and 87%, respectively [1].

The prognostic factors associated with survival and success rates after RCT have also been of interest to both researchers and clinicians and have been broadly categorised, according to the time frame in relation to the RCT, as (I) pre-operative, including (a) patient-related factors, such as age, gender, medical status or ethnic origin; (b) operator-related factors, such as skill and experience; and (c) tooth-dependent factors, such as the health condition of the tooth, pulp or periodontium; (II) intra-operative, mainly related to the quality of the RCT, such as inadequate obturation, short root canal fill or overfill; and (III) post-operative, mainly related to restorative aspects.

Preoperatively, the absence of a periapical radiolucency; intra-operatively, the presence of root filling without voids and extending up to 2 mm within the radiographic apex; and post-operatively, the quality of the coronal restoration were the most significant prognostic factors for endodontic success identified in a systematic review [5]. In terms of survival, the lack of a crown restoration after RCT, whether the treated tooth had mesial and distal proximal contacts, whether the tooth was functioning as an abutment for removable or fixed prosthesis and whether it was a molar, have been identified as the most significant factors for failure after RCT [1]. Furthermore, long-term observations have shown that tooth loss due to non-endodontically related causes, such as periodontitis, caries and vertical root fractures, may significantly influence the survival of endodontically treated teeth (ETT) [6–9].

Studies evaluating the long-term (> 20 years) survival and success of ETT are very few with no data exceeding 30 years of follow-up. It is, therefore, the primary objective of this retrospective observational study to evaluate the long-term survival rates of ETT. The secondary objectives aimed at evaluating (i) prognostic factors associated with tooth survival and (ii) long-term endodontic success .

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a longitudinal retrospective observational case series study based on a sample of patients with ETT treated by an experienced endodontist (GV) in a private dental practice in Verona, Italy, between 1979 and 2016.

Because of the use of only retrospective fully anonymized data, this study was a nonintervention clinical trial, adopting a standardized nonexperimental protocol, without the need for local review board approval according to the European Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (CPMP/ICH/135/95).

The manuscript was written in accordance with the recommendations for reporting clinical case series studies [10].

These patients received the following pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative treatment protocols:

-

Clinical and radiographic evaluations

Patients were clinically and radiographically examined by a single endodontist (GV) who established the treatment plan. The periodontal evaluation included the presence of plaque and bleeding on probing, probing pocket depths (PPD), marginal recession and clinical attachment levels (CAL), registered in 6 sites per tooth with a manual periodontal probe (PCP-UNC 15, Hu-friedy). Furthermore, bruxism was diagnosed clinically and from study casts by evaluating the presence of tooth wear. Full-mouth periapical radiographs were taken with the paralleling technique using a long cone with a ring XCP holder.

-

Initial preparation and treatment planning

Patients received periodontal therapy including oral hygiene instructions, supra and subgingival root instrumentation and periodontal surgery, depending on the periodontal diagnosis. If indicated by the degree of bruxism, an occlusal night guard was applied.

-

Endodontic and restorative treatment

Between 1979 and 1995, teeth requiring RCT had their root canals prepared and filled using the Schilder technique [11–13]. In brief, after isolation with a rubber dam, the pulp chamber was opened with a diamond bur (Intensiv 206, Intensiv, Grancia, Switzerland), and the canals were identified. These were scouted by using #08, #10 and #15 stainless steel files before preflaring with #1 and #2 Gates burs. The working length was determined on periapical radiographs at 0.5 mm coronal to the radiographic apex until 1991 and, thereafter, using an electronic apex locator (Osada Electric Co., LTD. Apit or Endex, Japan) at ‘0’ reading position. The ‘step-back’ procedure was then adopted using a sequence of stainless-steel files. Gutta-percha was compacted vertically with heat carriers (OP and OOP; from 1991 Touch’n Heat, Analytic Technologies, Redmond, WA, USA and from 2000 with System B, Sybronendo). Back packing was accomplished with the Obtura syringe (Obtura Spartan, Foothill Ranch, CA, USA).

From 1995 onwards, canals were prepared using a rotatory technique. The coronal third of the canal was enlarged with Gates Glidden drills 1 and 2 followed by a modified batt drill (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), while the apical portion was instrumented with pre-curved stainless-steel Hedström files (Dentsply Maillefer) with increasing diameters up to 20, without apical pressure. The apical diameter was recorded using light-speed instruments (Lightspeed LSX Instrument, Discus dental, Culver City, CA, USA). The largest diameter that could not bypass the working length was chosen as the apical diameter. Then, a step-back technique with increasing diameters of light-speed instruments was used to reach the previously prepared coronal third. All canals, except those presenting exudation, were closed in one session, which were provisionally medicated with calcium hydroxide. Gutta-percha cones were used to obturate the canals. The master cone was dipped into cement (Pulp Canal Sealer™, Kerr until 2000 and after that AH Plus™, Dentsply) and well adapted to the canal. Accessory gutta-percha cones where introduced. Excess gutta-percha was removed and vertically compacted with a heat carrier (Touch’n Heat or System b) and endodontic compactors (Thompson Dental Meg CO USA Tactile Tone SS Dr. Vignoletti plugger). In both techniques, 3.5% sodium hypochlorite was used as a disinfectant.

Upon completion of RCT, a direct filling or a permanent core was placed in the access cavity, depending on the remaining tooth structure and the operator’s choice. Similarly, the choice of restorative therapy depended on the remaining tooth structure. If cusp coverage was needed, a crown or onlay was constructed. If a cast metal (precious alloy) post and core or a fibre post were required, the gutta-percha root filling was cut back leaving at least 4 mm of root filling apically. Then, the tooth was restored with a temporary post-retained crown, and once manufactured, the definitive restoration was cemented.

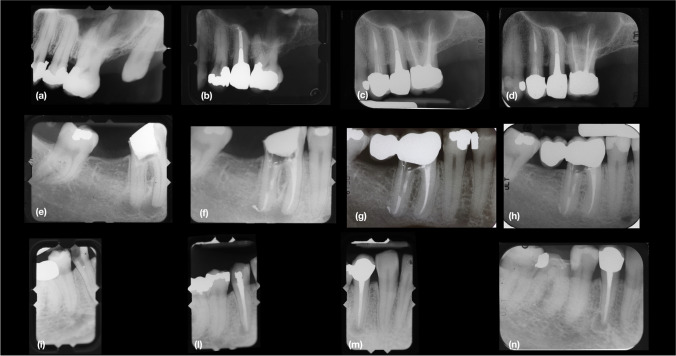

A final radiograph was taken after the restoration, and then, subsequent control radiographs were taken at 1 year and, thereafter, every 2 years (Fig. 1).

-

Recall programme

After the RCT and tooth restoration, patients entered a recall programme at intervals that varied between 1 to 4 times per year, depending on their periodontal status and the degree of the patient’s oral hygiene. At each periodic recall visit, a dentist or dental hygienist provided professional supra-gingival biofilm removal, as well as reinforced oral hygiene instructions. If indicated, sub-gingival instrumentation with ultrasounds and curettes was carried out. Approximately every 2 years, based on the ‘as low as reasonably achievable optimisation’ concept, peri-apical radiographs were taken in the posterior quadrants to monitor the occurrence of caries and periodontitis. Selective grinding and control of the occlusal night guard were also performed when needed.

Fig. 1 .

(a), Tooth 2.5. pre-op periapical radiograph, year 1979. (b), Periapical radiograph after endodontic and restorative treatment with cast metal post and crown, year 1979. (c), Post-op periapical radiograph follow-up, year 2004. (d), Post-op periapical radiograph demonstrating success 37 years after primary endodontic treatment , year 2016. (e) Tooth 4.6. pre-op periapical radiograph, year 1982. (f), Periapical radiograph after endodontic treatment, year 1982. (g), Tooth 4.6. post-op periapical radiograph with restorative treatment with a fiber post and radiolucent composite material and a crown, follow-up year 2000. (h), Tooth 4.6. post-op periapical radiograph demonstrating success after 34 years follow-up, year 2016. (i), Tooth 4.4. pre-op periapical radiograph, year 1979. (l), Periapical radiograph after endodontic treatment, year 1979. (m), Post-op periapical radiograph follow-up with restorative treatment, year 2004. (n), Post-op periapical radiograph demonstrating survival in painless function 37 years after primary endodontic treatment, year 2016.

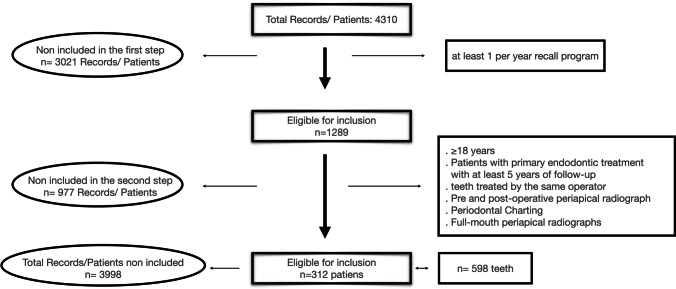

Selection of patients and ETT (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of patient inclusion in the study

Patients and ETT were eligible when fulfilling the following inclusion criteria:

Adults (> 18 years) with at least one endodontically treated tooth after at least 5 years of follow-up.

Patients in compliance with the recall programme within at least 1 time per year.

Teeth with baseline pre-operative and post-operative clinical and radiographical data.

Teeth were excluded if:

Treated with endodontic surgery, endodontic re-treatment, apexogenesis or apexification.

Third molars.

Data collection

One researcher (ILV) screened 4310 dental records and selected patients treated up to the year 2016 using these referred criteria. The relevant pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative data were transferred into an Excel data sheet. Potential prognostic factors such as age, sex, diagnosis of bruxism, tooth type and position, probing pocket depth (PPD), pulp status (either necrotic or vital), presence of radiographic radiolucency, type of restoration and posts were registered (Table 1). In detail, pulp status was diagnosed with an electric pulp tester (Analytic Technology). Necrotic status was recorded when the electric pulp tester value was 80. Pre-operative radiographic radiolucency was scored as positive whenever any sign of apical or lateral radiolucency was evidenced on baseline radiographs. Probing pocket depth (PPD) represented the deepest recorded periodontal probing of the tooth after RCT.

Table 1.

Independent variables of the entire sample of 598 teeth, expressed as the absolute value (n) or proportion (%). At the patient level, out of 312 patients, 45.5% of the patients were men, and 54.5% were women. Out of these, 119 (38.1%) were diagnosed with bruxism, and 69 (22.1%) used a night guard. The mean age of the sample was 65.5 years (SD: 14.07). * n (87) refers to the number of teeth extracted for each category, ** n (73) refers to the number of unsuccessful teeth in each category

| Independent variables | n (598) | % | *n (87) Extraction |

**n (73) No success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 324 | 54.2 | 45 | 29 |

| Male | 274 | 45.8 | 42 | 44 |

| Bruxism | ||||

| Yes | 215 | 36 | 25 | 27 |

| No | 383 | 64 | 62 | 46 |

| Night guard | ||||

| Yes | 123 | 20.6 | 8 | 12 |

| No | 475 | 79.4 | 79 | 61 |

| Dental arch | ||||

| Maxillary | 347 | 58 | 51 | 40 |

| Mandibular | 251 | 42 | 36 | 33 |

| Type of tooth | ||||

| Incisors | 112 | 18.7 | 15 | 6 |

| Maxillary | 78 | 13 | 9 | 2 |

| Mandibular | 34 | 5.7 | 6 | 4 |

| Canines | 44 | 7.4 | 11 | 5 |

| Maxillary | 28 | 4.7 | 7 | 3 |

| Mandibular | 16 | 2.7 | 4 | 2 |

| Premolars | 175 | 29.3 | 22 | 24 |

| Maxillary | 92 | 15.4 | 14 | 12 |

| Mandibular | 83 | 13.9 | 8 | 12 |

| Molars | 267 | 44.6 | 39 | 38 |

| Maxillary | 149 | 24.9 | 21 | 29 |

| Mandibular | 118 | 19.7 | 18 | 9 |

| Endodontic treatment | ||||

| Manual | 199 | 33.3 | 46 | 33 |

| Rotatory | 399 | 66.7 | 39 | 40 |

| Pulp status | ||||

| Vital | 429 | 71.7 | 59 | 45 |

| Necrotic | 169 | 28.3 | 28 | 28 |

| Pre-operative radiographic radiolucency | ||||

| Yes | 295 | 49.3 | 57 | 53 |

| No | 303 | 50.7 | 30 | 20 |

| Post-operative radiographic radiolucency | ||||

| Yes | 22 | 96.3 | 82 | 22 |

| No | 576 | 3.7 | 4 | 51 |

| Probing pocket depth | ||||

| (1–3 mm) | 238 | 39.8 | 36 | 7 |

| (4–5 mm) | 263 | 44 | 33 | 21 |

| (≥ 6 mm) | 97 | 16.3 | 18 | 45 |

| Fibre post | ||||

| Yes | 193 | 32.3 | 15 | 17 |

| No | 405 | 67.7 | 72 | 56 |

| Cast metal post (precious alloy) | ||||

| Yes | 93 | 15.6 | 30 | 16 |

| No | 505 | 84.4 | 57 | 57 |

| Restoration | ||||

| Direct filling | 182 | 30.4 | 28 | 11 |

| Single crown | 217 | 36.2 | 28 | 31 |

| Dental bridge | 197 | 32.9 | 29 | 29 |

| Overdenture | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 2 |

| Adjacent tooth | ||||

| Not present | 234 | 39.1 | 48 | 38 |

| Natural tooth | 220 | 36.8 | 21 | 21 |

| Crown or bridge | 125 | 20.9 | 17 | 14 |

| Overdenture or removable partial denture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Implant supported crown | 19 | 3.2 | 1 | 0 |

| Overlay/onlay | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pontic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antagonist: | ||||

| Not present | 22 | 3.7 | 4 | 4 |

| Natural tooth | 337 | 56.4 | 35 | 32 |

| Crown or bridge | 193 | 32.3 | 39 | 37 |

| Overdenture or removable partial denture | 4 | 0.7 | 3 | 0 |

| Implant supported crown | 13 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Overlay/onlay | 4 | 0.7 | 1 | 0 |

| Pontic | 25 | 4.2 | 5 | 0 |

Outcome variables

Tooth survival (primary outcome) was based on maintenance of the ETT, provided it was painless and in function [14]. At the patient level, whenever a tooth was extracted, the patient entered the category ‘no survival’.

Tooth mortality was accounted when the ETT was extracted. Extraction time was recorded as the time interval (measured in years) between the end of the RCT and the extraction date. The reason for tooth extractions were recorded and were divided into the following categories: (I) untreatable caries, (II) fracture of the crown, (III) vertical root fracture, (IV) periodontal disease progression and (V) endodontic inflammation. In detail, teeth were extracted when the decay or fracture of the crown was incompatible with the tooth restoration, when a vertical root fracture was diagnosed and the tooth was incompatible with function and comfort and when the residual periodontal support was incompatible with function and comfort and could not be improved with additional periodontal therapy.

Endodontic success (secondary outcome) was evaluated clinically and radiographically using the criteria defined in the Toronto study [14]. In brief, success or ‘healed’ was defined as absence of any radiographic sign of apical periodontitis with a concomitant lack of any clinical signs and symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using both the subject (survival analysis) and the tooth as the statistical unit. Descriptive statistics utilized means and standard deviations (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), as well as proportions, depending on the type of variable (quantitative or qualitative). A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed considering (a) tooth extraction/survival and (b) endodontic success as the outcome variables, and different tooth-related factors were assessed: tooth type (incisor, canine, premolar and molar), location (mandible vs maxilla) and position.

A regression analysis was performed to evaluate risk indicators associated with tooth extraction/survival. To identify the variables to include in the logistic regression model, a bivariate chi-square analysis was performed with all the independent variables (Table 1), and if significant in this first step, they were included in the final regression analysis. Logistic regression results were presented as odds ratios (OR). Survival curves were further constructed to compare survival distributions according to the identified risk indicators. The long-rank test (Mantel-Cox test) was used to compare these survival distributions, and the p value was adjusted for multiple comparisons.

IBM SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses, and the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Study population

The characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. Three hundred and twelve patients with a mean age of 65.5 (SD 14.07) and 598 teeth were included in the study. Between 1979 and 1994, 199 (33.3%) teeth were treated according to the Schilder’s technique, whereas between 1995 and 2016, 399 (66.7%) were treated according to a crown-down rotary technique. The majority of ETT were molars (267; 44.7%), followed by premolars (175; 29.3%), incisors (112; 18.7%) and canines (44; 7.4%). Regarding the type of restoration, the vast majority (414; 69.1%) were restored with prosthetic crowns, whereas 182 (30.4%) were direct amalgam or composite fillings.

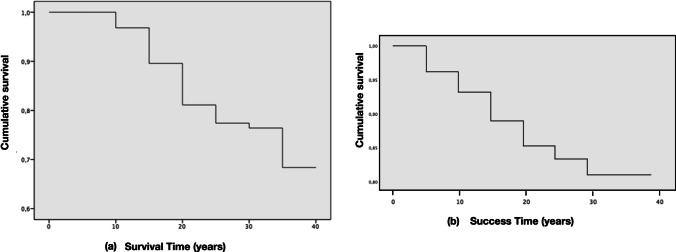

Tooth survival

The overall survival rate after a mean follow-up period of 21 years was 85.5% (511 out of 598; 95% CI: 81% to 88%) and 81.7% (255 out of 312; 95% CI: 77% to 85%) at the tooth and patient levels, respectively. The cumulative survival rate expressed by the Kaplan-Meier analysis curve showed that the probability of a tooth surviving 10, 20, 30 and 37 years after endodontic treatment was 97%, 81%, 76% and 68%, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3a). The mean estimated tooth survival was 31.64 years (95% CI: 30.62 to 32.66) for both arches, 31.6 years (95% CI: 30.27 to 32.92) for the maxillary teeth and 31.76 years (95% CI: 30.21 to 33.32) for the mandibular teeth. Tooth survival was not affected by tooth position (p = 0.679), tooth type (molars, premolars, cuspids, incisors; p = 0.362) and whether the tooth was in the mandible or maxilla (p = 0.758).

Table 2.

Mortality table for the survival of ETT. The number of terminal events equals the number of teeth lost in each interval

| Interval start time (years) | Number of teeth entering in each time interval. Survival |

Number of teeth withdrawn during this interval | Number of teeth exposed to risk | Number of terminal events. Survival |

Probability of surviving (%) | Cumulative survival at the end of each interval | 95% CI of cumulative success proportion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| 0 | 598 | 0 | 598 | 0 | 100 | 1.00 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 598 | 62 | 567 | 18 | 97 | .97 | 0.9504 | 0.9896 |

| 10 | 518 | 180 | 428 | 32 | 93 | .90 | 0.8804 | 0.9196 |

| 15 | 306 | 83 | 264 | 25 | 91 | .81 | 0.7708 | 0.8492 |

| 20 | 198 | 90 | 153 | 7 | 95 | .77 | 0.7308 | 0.8092 |

| 25 | 101 | 45 | 78 | 1 | 99 | .76 | 0.7012 | 0.8188 |

| 30 | 55 | 34 | 38 | 4 | 89 | .68 | 0.6016 | 0.7584 |

| 35 | 17 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 100 | .68 | 0.6016 | 0.7584 |

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier function curves of 598 endodontically treated teeth. (a) Survival and (b) Endodontic Success

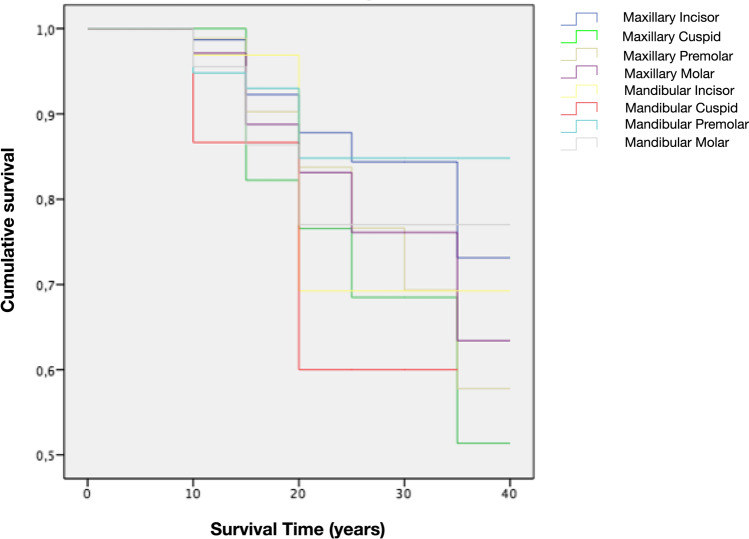

Tooth mortality

Eighty-seven teeth representing 14.5% of the entire sample were extracted after an overall mean time of 14.1 (95% CI: 12.84 to 15.37) years. When analysing the Kaplan-Meier curves by tooth type, all teeth presented similar survival rates (approximately 80%) up to 20 years post-endodontic treatment. Afterwards, mortality rates varied considerably with maxillary cuspids being the most frequently lost teeth (53.7% survival rate), whereas mandibular premolars were the least (85% survival) (Fig. 4). The reasons for tooth extraction were caries (1.7%), fracture of the crown (2.2%), vertical root fracture (4.8%) and periodontal disease progression (5.9%) with no statistically significant differences (p = 0.671) (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier function survival curves based on tooth position

Table 3.

Causes of extraction (absolute value, % of the extracted sample and total sample), mean (95% CI), and median time to extraction (IQR)

| n | % of the extracted sample | % total sample | Mean time to extraction (years) | 95% CI (lower) | 95% CI (upper) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of extraction | 100 | 14.6 | 14.103 | 12.842 | 15.365 | |

| Vertical root fracture | 29 | 33.3 | 4.8 | 14.069 | 11.718 | 16.420 |

| Periodontal disease progression | 35 | 40.2 | 5.9 | 13.429 | 11.887 | 14.971 |

| Caries | 10 | 11.5 | 1.7 | 15.900 | 10.990 | 20.810 |

| Crown fracture | 13 | 15 | 2.2 | 14.615 | 10.839 | 18.392 |

| Endodontic inflammation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Prognostic factors for extraction/survival

Table 4 depicts the chi-square analysis indicating the variables used for the logistic regression analysis. PPD ≤ 5 mm (OR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.54–0.86; p = 0.001), use of a night guard (OR = 0.34; 95% CI: 0.13–0.86; p = 0.023) and use of a fibre post (OR = 0.47; 95% CI: 0.24–0.91; p = 0.026) were protective factors associated with tooth survival. Conversely, the presence of a cast metal post (OR = 2.14; 95% CI: 1.14–4.01; p = 0.018) and pre-operative presence of periapical radiolucency (OR = 1.87; 95% CI: 1.07–3.28; p = 0.028) were factors significantly associated with tooth extraction.

Table 4.

The bivariate (chi-square) and logistic regression analyses for survival/extraction. Statistically significant variables according to the bivariate chi-square (*) analysis were included in the logistic regression analysis. Significant risk indicators are expressed as odds ratio (OR) (*). B: logistic regression coefficient (the exponentiation of the B coefficient, EXP(B), is the odds ratio). Comparisons of survival distributions according to the significant risk indicators were performed using the log-rank test (significant differences are expressed as **). The level of significance was set at p < 0.005.

| Chi-square |

p value (chi-square) |

B (logarithm of the OR) |

p value (logistic regression) |

OR EXP(B) |

95% CI for OR (lower) |

95% CI for OR (upper) |

Log-rank test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 3.692 | 0.055 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.247 | 0.619 | ||||||

| Dental arch | 0.015 | 0.204 | ||||||

| Diagnosis of bruxism | 2.303 | 0.129 | ||||||

| Use of night guard | 8.061 | 0.005* | −1.088 | 0.023* | 0.337 | 0.132 | 0.860 | 0.036** |

| Pulp status | 0.773 | 0.379 | ||||||

| Radiographic radiolucency | 9.210 | 0.002* | 0.628 | 0.028* | 1.874 | 1.071 | 3.277 | < 0.001** |

| Radiographic healing | 1.229 | 0.268 | ||||||

| Fiber_post | 10.526 | 0.001* | −0.756 | 0.026* | 0.469 | 0.242 | 0.912 | 0.425 |

| Cast Metal_post | 27.782 | 0.000* | 0.759 | 0.018* | 2.137 | 1.137 | 4.015 | 0.082 |

| PPD < 5 mm | 18.411 | 0.000* | -0.387 | 0.001* | 0.679 | 0.538 | 0.858 | < 0.001** |

| Single unit crown | 1.805 | 0.179 | ||||||

| Dental bridge | 18.307 | 0.000* | 0.400 | 0.766 | 1.492 | 0.107 | 20.777 | |

| Dental bridge with extension | 1.720 | 0.190 | ||||||

| Dental bridge without extension | 16.948 | 0.000* | 0.239 | 0.855 | 1.271 | 0.097 | 16.726 | |

| No adjacent tooth | 11.000 | 0.001* | 0.289 | 0.403 | 1.334 | 0.678 | 2.625 | |

| Adjacent natural tooth | 7.007 | 0.008* | 0.079 | 0.846 | 1.082 | 0.488 | 2.402 | |

| Adjacent crown or bridge | 0.640 | 0.424 | ||||||

| No antagonist | 3.348 | 0.067 | ||||||

| Antagonist natural tooth | 10.762 | 0.001* | −0.428 | 0.128 | 1.082 | 0.488 | 2.402 | |

| Antagonist crown or bridge | 0.875 | 0.675 |

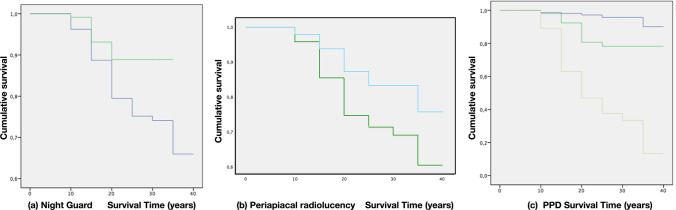

Survival curves were further constructed to evaluate survival distributions comparing the identified risk indicators. Only PPD < 5 mm, the presence of periapical radiolucency and use of a night guard demonstrated statistically significant differences (Table 4, Figs. 5a–c and 5).

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier function survival curves (a) comparing patients using (green line) or not using (blue line) the night guard, (b) comparing teeth with (green line) or without periapical radiolucency (blue line) and (c) comparing teeth with 1-3 mm PPD (blue line), 4-5 mm PPD (green line) and > 6 mm PPD (yellow line)

Endodontic success

The overall success rates of ETT were 87.8% (95% CI: 84 to 90%) and 80.8% (95% CI: 75 to 86%) at the tooth and patient levels, respectively. Cumulative success expressed by the Kaplan-Meier curve analysis showed that treatment success rates at 10, 20, 30 and 37 years were 93%, 85%, 81% and 81%, respectively (Table 5, Fig. 3b). Success rates were not affected by tooth position (ranging from 97.4% for upper incisors to 84.6% for upper molars, p = 0.210), tooth type (molars: 85.8%, premolars: 86.3%, cuspids: 88.6%, incisors: 94.6%, p = 0.068) and whether the tooth was in the mandible (86.9%) or maxilla (88.5%) (p = 0.413). Only when comparing incisors versus molars, and maxillary incisors versus mandibular molars, was a tendency towards significance observed (p = 0.09 and p = 0.056, respectively).

Table 5.

Mortality table for the success of ETT. The number of terminal events equals the number of teeth lost in each interval

| Interval start time (years) | Number of teeth in each time interval. Success |

Number of teeth withdrawn during this interval | Number of teeth exposed to risk. Success |

Number of terminal events. Success | Probability of surviving. Success (%) |

Cumulative Success at the end of each interval | 95% CI of cumulative success proportion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| 0 | 598 | 0 | 598 | 22 | 96 | .96 | 0.9404 | 0.9796 |

| 5 | 576 | 71 | 540 | 17 | 97 | .93 | 0.9104 | 0.9496 |

| 10 | 488 | 184 | 396 | 18 | 95 | .89 | 0.8704 | 0.9096 |

| 15 | 286 | 93 | 239 | 10 | 96 | .85 | 0.8108 | 0.8892 |

| 20 | 183 | 91 | 137 | 3 | 98 | .83 | 0.7908 | 0.8692 |

| 25 | 89 | 38 | 70 | 2 | 97 | .81 | 0.7512 | 0.8688 |

| 30 | 49 | 34 | 32 | 0 | 100 | .81 | 0.7512 | 0.8688 |

| 35 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 0 | 100 | .81 | 0.7512 | 0.8688 |

Discussion and conclusion

This sample, including 312 patients and 598 ETT, demonstrated high tooth survival rates, especially during the first 20 years after treatment. In fact, at 10 and 20 years post treatment, the probability of survival for an ETT was 97% and 81%, respectively. These results are consistent with other clinical studies. After 10 years, Fonzar et al. [8] reported 93% survival rate, whereas Pirani et al. [15] and Fernandez et al. [16] reported 87.1% and 91.6%, respectively. After 25 years, the results from the present study indicated that 77% of ETT were still in painless function. These results were consistent with what was reported by Prati et al. [9] with a cumulative survival rate of 79% at 20 years but well beyond the 46% presented by Lee et al. [17] after 25 years. After 30 years of follow-up, the reported survival rate in this study was 76%. These results are in line with data from another study published by Mareschi et al. [18] which demonstrated 70% cumulative survival rates after 29 years. In this latter study, patients were treated by only one expert operator in a private practice with similar treatment procedures, which justifies the very similar findings. Regarding the reasons for tooth extraction, most teeth were extracted due to vertical root fracture (33.3% of the extracted teeth sample) and progression of periodontitis (40.2% of the extracted sample) (Table 6). These data are consistent with percentages reported by Mareschi et al. [18] and Fonzar et al. [8] who demonstrated that vertical root fracture and periodontitis were the most represented reasons for tooth extraction, respectively. It is noteworthy to highlight that no tooth was extracted due to endodontic inflammation.

Table 6.

Distribution of the sample in relation to the causes of extraction and tooth type: 1, maxillary incisor; 2, mandibular incisor; 3, maxillary canine; 4, mandibular canine; 5, maxillary 1st premolar; 6, maxillary 2nd premolar; 7, mandibular 1st premolar; 8, mandibular 2nd premolar; 9, maxillary 1st molar; 10, maxillary 2nd molar; 11, mandibular 1st molar; 12, mandibular 2nd molar

| Tooth type | n | Mx. Inc. 1 |

Mb. Inc. 2 |

Mx Can. 3 |

Mb Can. 4 |

Mx 1Prem. 5 |

Mx 2Prem. 6 |

Mb 1Prem. 7 |

Mb 2Prem. 8 |

Mx 1Mol. 9 |

Mx 2Mol. 10 |

Mb 1Mol. 11 |

Mb 2Mol. 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of extraction | |||||||||||||

| VRF | 29 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| Periodontal disease progression | 35 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Caries | 10 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Crown fracture | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Endodontic inflammation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Even though survival analysis is important to evaluate the performance of any therapeutic intervention, it is even more relevant to study the prognostic factors associated with this survival since these may guide treatment decisions and preventive measures. In this study, the logistic regression model identified PPD ≤ 5 mm as a protective factor (OR = 0.68), influencing the tooth survival distribution, as shown in Fig. 5c. In fact, at 30 years, only approximately 30% of > 5 mm PPD teeth were still in function, as compared to 80% of teeth with PPD ≤ 5 mm (Fig. 5). This finding is consistent with data from RCTs in which the odds of failure of ETT increased significantly in teeth diagnosed with mild (OR = 1.9) or moderate (OR = 3.1) periodontitis as compared to periodontally healthy teeth [19]. Similarly, it is well known that the presence of residual deep PPD (≥ 6 mm) was identified as the main risk factor for tooth loss after periodontal treatment [20, 21]. Another significant factor associated with tooth loss was pre-operative radiographic radiolucency. Teeth with radiographic radiolucency are almost two times (OR 1.87) as likely to be extracted than those without (Fig. 5b). This finding is in line with data from a very similar long-term study in which the presence of periapical radiolucency was correlated to higher odds (OR 1.9) of tooth extraction [18].

In contrast with other studies reporting molar teeth as a prognostic factor for tooth loss [1], tooth type was not significant in the present study. A reason for this difference may be related to the operating skills of the practitioner performing the endodontic therapy. There is evidence that suggests when it is carried out by an endodontist, there is a higher probability of tooth survival at 5 years, compared to a general practitioner (98.1% vs. 89.7%, respectively) [22]. In this investigation, all endodontic treatments were always performed by the same endodontist (GFV), which may also explain the lack of influence of the tooth type on survival rates.

The post-operative restorative factors that influenced tooth survival were the use of cast metal or fibre posts and the use of a night guard. Teeth with a cast metal post had two times (OR 2.13; CI 95% (1.137–4.015)) higher chance of being extracted. Conversely, the use of fibre posts was associated with 0.026 times lower chances of being extracted (OR 0.469; CI 95% (0.242–0.912)). These findings agree with other studies demonstrating a correlation between retentive metal intra-canal systems and lower survival rates [16, 23]. Similarly, the protective effect of fibre posts has been reported [24, 25].

While the protective role of a crown restoration after root canal treatment has been reported in some studies [23, 26] and systematic reviews [1], others have reported that placing a crown restoration on a ETT increased the risk of any complication by five times [27]. In the present study, crowned ETT did not present higher tooth survival. A possible explanation to this discrepancy may be related to the number of residual remaining walls, rather than the type of restoration [25]. Indeed, in this study, the selection of restorative therapy was based on the residual tooth structure, always selecting crown restorations when cusp coverage was needed. Furthermore, recent data based on systematic review and meta-analysis [28] evaluating the clinical performance of direct composite resin versus indirect restorations on ETT demonstrated no differences in tooth survival, in line with results from the present study. The importance of occlusal protection was also demonstrated in this study by identifying, in the logistic regression model, the use of a night guard as a protective factor influencing the tooth survival distribution (Fig. 5a).

In the present study, the overall success rates of ETT of 87.8% and 80.8% at the tooth and patient levels, respectively, were high and in line with data reported in the literature [8]. When analysing the cumulative endodontic success rates, reported values in the life table analysis were 93%, 85%, 81% and 81% after 10, 20, 30 and 37 years, respectively. These results are higher than what has been presented in systematic reviews with reported success rates of 82.8 % at 5 years [29] or in individual studies with success rates of 61% at 8 years [26]. Similarly, when looking at long-term follow-up, Lee et al. [17] observed 29% success rates after 25 years. These latter success rates are lower than the ones observed in the present study, which were 83% and 81% after 25 and 37 years, respectively. Several reasons may explain the major differences among the two studies, such as (I) biases in the method of visualisation of the lesion related to the two-dimensional radiographs, (ii) diverse criteria used to evaluate endodontic success, (iii) private practice-based versus teaching hospital-based study and (iv) different endodontic and restorative procedures [30, 31].

Like any retrospective observational case series, this study presents several limitations, largely dependent on the availability and accuracy of the data records. Despite this, an effort was made to include all patients attending the practice recall programme at least once per year with existing records, including more than 30 clinical and radiographic variables. Another important factor that must be considered is that due to the 5-year follow-up inclusion criteria, ETT with early (1–4 years) failures may have been lost during case selection. This selection bias, inherent to the retrospective nature of this evaluation, is a strong limitation that may justify the lack of extractions due to endodontic inflammation and consequently mask, in part, the overall data of survival of this case series. Notwithstanding this fact, the evaluation of two private practice-based studies using a protocol similar to the one utilized in the present investigation reported that the early failures in the 0–5 years’ time frame was approximately 2–3% of the entire sample (8, 18). These data should be clearly considered when drawing conclusions. Another aspect that needs to be considered is the fact that treatment protocols for restorative procedures and materials have changed slightly throughout the entire study period, and this is a potential confounding factor that may in part have affected the outcomes. It is also important to highlight that the external validity of this study is limited since a single operator in one clinical centre performed all the RCTs, and hence, the reported outcomes need to be extrapolated with caution to all clinical scenarios.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the longest follow-up study that demonstrates very high cumulative survival (68%) and success (81%) rates of ETT after 37 years of follow-up. These data, within the context of modern clinical dentistry, with a clear tendency to oversimplifying treatment plans and recurring to extraction of pathologically affected dentitions and replacing them with dental implants, should clearly encourage clinicians towards a conservative approach when treating the disease and maintaining the natural dentition.

In conclusion, within the limits of the present study, high long-term survival and success rates after primary RCT may be expected. The presence of deep periodontal pockets (≥ 6 mm), the lack of occlusal protection (no use of a night guard) and pre-operative apical radiolucency are the most significant prognostic factors associated with tooth extraction.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the kind help and support of Mrs. Elena Mantica and Mrs. Anna Toffolon in collecting the original clinical and radiographical records of the patients included in the present investigation.

Author contributions

Isabel Lopez-Valverde: literature review, data collection, analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting

Fabio Vignoletti: study concept/design, data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the manuscript

Gianfranco Vignoletti: execution of the clinical phase, data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the manuscript

Conchita Martin: data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, critical review of the manuscript

Mariano Sanz: project supervisor, study concept/design, data analysis and interpretation, critical review of the manuscript

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Isabel López-Valverde, Email: isabel.lopezvalverde@gmail.com.

Fabio Vignoletti, Email: fabiovig@ucm.es.

Gianfranco Vignoletti, Email: info@studiodentisticovignoletti.it.

Conchita Martin, Email: mariacom@ucm.es.

Mariano Sanz, Email: marsan@ucm.es.

References

- 1.Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. Tooth survival following non-surgical root canal treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Int Endod J. 2010;43(3):171–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman S, Mor C. The success of endodontic therapy--healing and functionality. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2005;32:493–503. doi: 10.1080/19424396.2004.12223997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature – part 1. Effects of study characteristics on probability of success. Int Endod J. 2007;40:921–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman S. Prognosis of initial endodontic therapy. Endod Topics. 2002;2(1):59–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-1546.2002.20105.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature - part 2. Influence of clinical factors. Int Endod J. 2008;41:6–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricucci D, Russo J, Rutberg M, Burleson JA, Spångberg LSW. A prospective cohort study of endodontic treatments of 1,369 root canals: results after 5 years. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:825–842. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergenholtz G. Assessment of treatment failure in endodontic therapy. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43:753–758. doi: 10.1111/joor.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonzar F, Fonzar A, Buttolo P, Worthington HV, Esposito M. The prognosis of root canal therapy: a 10-year retrospective cohort study on 411 patients with 1175 endodontically treated teeth. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2009;2:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prati C, Pirani C, Zamparini F, Gatto MR, Gandolfi MG. A 20-year historical prospective cohort study of root canal treatments. A Multilevel analysis. Int Endod J. 2018;98:115. doi: 10.1111/iej.12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabs DA. Improving the reporting of clinical case series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(5):900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schilder H. Filling root canals in three dimensions. Dent Clin North Am; 1967. pp. 723–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilder H. Preparation of the root canal. Mondo Odontostomatol. 1976;18:8–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schilder H. Filling root canals in three dimensions. J Endod. 2006;32:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman S, Abitbol S, Lawrence HP. Treatment outcome in endodontics: the Toronto study. Phase 1: initial treatment. J Endod. 2003;29:787–793. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200312000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirani C, Chersoni S, Montebugnoli L, Prati C. Long-term outcome of non-surgical root canal treatment: a retrospective analysis. Odontology. 2015;103:185–193. doi: 10.1007/s10266-014-0159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández R, Cardona JA, Cadavid D, Álvarez LG, Restrepo FA. Survival of endodontically treated roots/teeth based on periapical health and retention: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. J of Endod. 2017;43:2001–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee AHC, Cheung GSP, Wong MCM. Long-term outcome of primary non-surgical root canal treatment. Clin Oral Invest. 2012;16:1607–1617. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0664-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mareschi P, Taschieri S, Corbella S. Long-term follow-up of nonsurgical endodontic treatments performed by one specialist: a retrospective cohort study about tooth survival and treatment success. Int J Dentistry. 2020;2020:1. doi: 10.1155/2020/8855612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalighinejad N, Aminoshariae A, Kulild JC, Wang J, Mickel A. The influence of periodontal status on endodontically treated teeth: 9-year survival analysis. J Endod. 2017;43:1781–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claffey N, Kelly A, Bergquist J, Egelberg J. Patterns of attachment loss in advanced periodontitis patients monitored following initial periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:523–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb01820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matuliene G, Pjetursson BE, Salvi GE, Schmidlin K, Brägger U, Zwahlen M, Lang NP. Influence of residual pockets on progression of periodontitis and tooth loss: results after 11 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:685–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alley BS, Kitchens GG, Alley LW, Eleazer PD. A comparison of survival of teeth following endodontic treatment performed by general dentists or by specialists. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yee K, Bhagavatula P, Stover S, Eichmiller F, Hashimoto L, MacDonald S, Barkley G. Survival rates of teeth with primary endodontic treatment after core/post and crown placement. J Endod. 2018;44:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guldener KA, Lanzrein CL, Siegrist Guldener BE, Lang NP, Ramseier CA, Salvi GE. Long-term clinical outcomes of endodontically treated teeth restored with or without fiber post-retained single-unit restorations. J Endod. 2017;43:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrari M, Vichi A, Fadda GM, Cagidiaco MC, Tay FR, Breschi L, Polimeni A, Goracci C. A randomized controlled trial of endodontically treated and restored premolars. J Dent Res. 2012;91:72S–78S. doi: 10.1177/0022034512447949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: an epidemiological study. J Endod. 2004;30:846–850. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000145031.04236.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontoriero DIK, Grandini S, Spagnuolo G, Discepoli N, Benedicenti S, Maccagnola V, Mosca A, Ferrari Cagidiaco E, Ferrari M. Clinical outcomes of endodontic treatments and restorations with and without posts up to 18 years. J Clin Med. 2021;10:908. doi: 10.3390/jcm10050908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Kuijper MCFM, Cune MS, Özcan M, Gresnigt MMM. Clinical performance of direct composite resin versus indirect restorations on endodontically treated posterior teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;31:1. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng YL, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J. 2011;44:583–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernández R, Cadavid D, Zapata SM, Álvarez LG, Restrepo FA. Impact of three radiographic methods in the outcome of nonsurgical endodontic treatment: a five-year follow-up. J Endod. 2013;39:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abella F, Patel S, Durán-Sindreu F, Mercadé M, Bueno R, Roig M. An evaluation of the periapical status of teeth with necrotic pulps using periapical radiography and cone-beam computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2014;47:387–396. doi: 10.1111/iej.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.