Abstract

Within recent decades glucagon receptor (GcgR) agonism has drawn attention as a therapeutic tool for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. In both mice and humans, glucagon administration enhances energy expenditure and suppresses food intake suggesting a promising metabolic utility. Therefore synthetic optimization of glucagon-based pharmacology to further resolve the physiological and cellular underpinnings mediating these effects has advanced. Chemical modifications to the glucagon sequence have allowed for greater peptide solubility, stability, circulating half-life, and understanding of the structure-function potential behind partial and “super”-agonists. The knowledge gained from such modifications has provided a basis for the development of long-acting glucagon analogues, chimeric unimolecular dual- and tri-agonists, and novel strategies for nuclear hormone targeting into glucagon receptor-expressing tissues. In this review, we summarize the developments leading toward the current advanced state of glucagon-based pharmacology, while highlighting the associated biological and therapeutic effects in the context of diabetes and obesity.

Keywords: Glucagon, Obesity, Diabetes, Dual-agonists, Tri-agonists, Biased agonism, Pharmacology

Highlights

-

•

GcgR agonism facilitates anti-obesogenic effects despite hyperglycemic properties.

-

•

Intracellular GcgR activity is primarily Gαs coupled and moderated by many intracellular factors.

-

•

Gcg analogue development is optimized from chemical and biological endpoints.

-

•

Partial, super, and biased Gcg analogues have not been extensively explored in vivo.

-

•

Unimolecular dual-/tri-agonist and Gcg-hormone conjugates are promising therapeutic horizons.

1. Introduction

Glucagon (Gcg) was identified in 1923 by Charles Kimball and John Murlin as an opposing factor to the glucose-lowering effect of insulin [101]. Within the next 30 years, greater characterization achieved first purification and crystallization of the glucagon peptide in 1953, first sequencing of the 29-amino acid peptide in 1957, and identification of the pancreatic alpha cell as the site of origin for endogenous secretion [169], [185], [19], [58]. The glucagon peptide is among the processed end-products of the 160-amino acid precursor peptide proglucagon. While proglucagon is expressed within the pancreatic alpha cells, the enteroendocrine L cells, and to a minor extent within the hypothalamus and brain stem, differential tissue expression of prohormone convertase 2 (PC2) and prohormone convertase 1/3 (PC1/3) allows for tissue-specific processing of proglucagon into either glucagon (via PC2) or glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2) via PC1/3 [122].

Pancreatic alpha cell secretion of glucagon is stimulated in response to hypoglycemia, prolonged fasting, exercise, and consumption of specific amino acids, while its release is modified via endocrine/paracrine inputs and the autonomic nervous system [131], [22], [61], [73], [75]. Endogenous release of Gcg stimulates an increase in circulating blood glucose, while exogenous administration demonstrates capacity to evoke hyperglycemia in healthy men and recover some diabetic patients from hypoglycemic comas [113], [47], [72]. Gcg acts primarily at the liver to raise circulating blood glucose levels via breakdown of carbohydrate-rich glycogen (glycogenolysis) or synthesis from non-carbohydrate substrates (gluconeogenesis) [171], [180], [52], [66]. The glucagon receptor (GcgR) is the cognate 7-transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) which facilitates transmission of glucagon binding into an intracellular signal. The GcgR is predominantly expressed in the liver, and to a lesser extent in extrahepatic tissues such as the brain, heart, kidney, adipose tissue, and gastrointestinal tract [122], [9].

1.1. Glucagon receptor antagonism for the treatment of T2D

Development towards obesity and its comorbidity type 2 diabetes (T2D) is often characterized with chronic elevations in blood glucose, which over time systematically leads to insulin desensitization, β-cell dysfunction, and a plasma profile high in triglycerides. The correlative elevation in blood glucose towards the development of these pathologies represents a therapeutically targetable node. In line with the activation of GcgR increasing systemic glucose levels, hyperglucagonemia is a hallmark occurrence associated with (non)fasted hyperglycemic exacerbation in obese and insulin resistant conditions [170]. Therefore, for obese and diabetic individuals, pharmacological interest in GcgR antagonism has been sought as an anti-hyperglycemic therapy. Knockouts, knockdowns, or pharmacological inhibition of the glucagon receptor in animal models are generally evidenced to improve glucose tolerance relative to controls through reductions in fasted blood glucose (without increased susceptibility to hypoglycemia) and improvements in post-prandial glycemic excursions (as demonstrated in mice with concomitant streptozotocin-induced beta-cell destruction) [108], [122], [32]. Similarly in healthy human subjects, acute administration of a GcgR antagonist or chronic administration of a GcgR antisense drug prevent glucagon-induced glycemic increases without severe side effects [137], [183], [98]. Clinical studies with T2D patients have demonstrated efficacy of small-molecule and peptide-based antagonists in decreasing fasting/post-prandial glucose levels and HbA1c without severe adverse effects or probability of hypoglycemia [31]. The first clinical candidate for a small-molecule GcgR antagonist was MK-0893 in which 80 mg daily treatment over 12-weeks demonstrated considerable efficacy in reducing fasted plasma glucose by − 34% and HbA1c by − 1.5% relative to placebo [74]. However, GcgR antagonism by MK-0893 also coincided with a 15% increase in circulating LDL-C and elevated alanine liver transaminase, which together represent adverse effects commonly seen across multiple small-molecule GcgR antagonists [31]. The antagonism-driven effects of increased circulating LDL-C and total cholesterol are suggested to occur through enhancements in intestinal cholesterol absorption as assessed by isotopically-labeled cholesterol consumption in humanized GcgR mice. In line with this, increases in circulating LDL-C and total cholesterol during GcgR antagonism were abolished with co-administration of the cholesterol absorption inhibitor Ezetimibe [74]. Other clinically developed small-molecule GcgR antagonists include PF-06291874, LY2409021, and LGD-6972 (RVT-1502), all of which have advanced to clinical trials but ultimately were not pursued further for the treatment of T2D or obesity due to the associated increases in circulating LDL-C, body weight, hepatic fat, and blood pressure [31]. Similarly, caveats within mouse models of GcgR signaling inhibition by partial or complete genetic deletion are the development of considerable phenotypes including increased pancreatic weight (predominantly due to α-cell hyperplasia), defects in hepatocyte lipid metabolism, and hepatocyte susceptibility to experimental liver injury [5]. Despite these adverse caveats, both diabetic mice and non-human primates respond well to treatment with an antagonistic monoclonal GcgR antibody that corrects hyperglycemia. Interestingly however, unlike the mice, responsive α-cell hyperplasia is notably absent in treated non-human primates, suggesting adverse effects of glucagon receptor inhibition to be variable across species [129].

The gluconeogenic nature of glucagon receptor agonism is considered valuable for defending against insulin-induced hypoglycemia, and also illustrates pharmacological antagonism as a means to limit glucagon-driven fasted and post-prandial hyperglycemia [119], [148], [190], [31], [97], [98]. However, while glucagon receptor antagonism was considered a popular mechanism for the treatment of T2D a few year ago, adverse effects have refocused the therapeutic approach toward glucagon receptor agonism.

1.2. Glucagon receptor agonism for the treatment of T2D and obesity

Contrary to GcgR antagonism, hyperglycemic liability has historically limited investigation into further agonism-directed therapeutic developments. Despite this, glucagon agonism holds anti-obesogenic and anti-diabetic potential. The primary physiological benefits of GcgR agonism in relation to obesity and diabetes are ligand-stimulated reductions in food intake and enhancements in systemic energy expenditure [102], [122], [3].

The mechanisms underlying GcgR agonism-associated reductions in food intake are not fully understood, and the extent of total reduction is variable between conditions and studies. Nonetheless, it is proposed that food intake reductions in both rats and humans occur via GcgR-expressing hepatic vagal nerve afferents to the hypothalamus, and direct action at the GcgR within the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC) [67], [68], [69], [85]. Regarding a potential explanation to the discrepancy in food intake reductions between studies, glucagon efficacy on satiety seems in part dependent on the state of ARC-localized CaMKKβ sensitivity within a GcgR/PKA/CaMKKβ/AMPK/AgRP axis, of which the obese state may negatively modulate [3].

Both acute and chronic GcgR agonism increase energy expenditure [102]. Energy expenditure enhancement associated with acute GcgR agonism predominately originates from substrate processing within hepatic glycogenolysis, and to a lesser extent gluconeogenesis [102], [136], [15]. Alternatively, enhancement in energy expenditure due to chronic GcgR agonism seems to primarily originate from an increase in sympathetic tone which ultimately escalates brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and browning of white adipose tissue [102]. The overall extent of glucagon-mediated energy expenditure enhancement is reliant on multiple intact systemic components which include: hepatic expression of GcgR, FGF21, farsenoid X receptor (FXR), and alanine transaminase (ALT); CNS-specific expression of β-klotho; and the system-wide occurrence of glucagon-induced hypoaminoacidemia [100], [102], [127], [130], [82]. Outside of glucagon’s anti-obesogenic energy expenditure effects, hepato-centric pathways of GcgR agonism have also been linked to reductions in hepatic lipid accumulation, improvements in systemic lipid metabolism, increases in hepatic ureagenesis, and alterations in the circulating amino acid profile [173], [191], [64], [65], [81].

Despite transient hyperglycemia, the direct benefits of GcgR agonism on satiety and energy expenditure position its pharmacology as a valuable anti-obesogenic option. However, additional anti-diabetic value resides in the downstream effects of GcgR agonism on whole-body insulin sensitivity – an effect independent of insulin secretion, the GLP-1 receptor, and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) [53], [99].

Glucagon administration has also been shown to induce β-cell insulin secretion through both glucose-dependent and glucose-independent mechanisms [158]. Glucagon-mediated enhancement in insulin secretion, independent of GcgR-mediated glucose production, has been suggested to occur via paracrine activation of the β-cell GLP-1 receptor in the post-prandial state [174], [2], [25]. Indeed, Gcg activates the GLP-1R within localized concentrations in the double-digit picomolar (pM) range, while it more specifically activates the GcgR at concentrations < 1 pM as exemplified in vitro [51]. Together, glucagon may act through concentration-dependent bi-specificity at the Gcg and GLP-1 receptor to induce insulin secretion at the β-cell.

The therapeutic potential of GcgR agonism has initiated efforts into pharmacological optimization of the glucagon peptide. This review will give an overview of the pharmacological details associated with the path of peptide development toward long-acting GcgR mono-agonists, followed by cutting-edge innovations in small-molecule glucagon conjugates and dual- and tri-agonists.

2. The physiological glucagon signaling system

The glucagon receptor is primarily a Gαs-coupled GPCR with additional associations to Gαq and Gαi [146], [186], [193]. Following glucagon binding, activity at the GcgR modulates the tissue response through a two-signal transduction system consisting of parallel cyclic AMP (cAMP) and calcium (Ca2 +) elevations [59], [62], [87]. Cyclic AMP production is considered a primary surrogate for ligand effectiveness at the GcgR. However, contention exists as to which intracellular system, Gαs or Gαq, is primarily mediating glucagon’s normal physiological role of hepatic glucose production in vivo [151], [188].

The GcgR (ant)agonist 1-N-α-trinitrophenylhistidine,12-homo-arginine)Glucagon (TH-Glucagon), despite evidence suggesting a lack of a GcgR-mediated cAMP response up to 1 μM stimulation, has shown considerable efficacy (40% of that of native glucagon) in stimulating glucose production and ureagenesis in isolated rat hepatocytes and guinea pigs [109], [186], [35]. It has been hypothesized that TH-Glucagon-induced activity occurs through intracellular increases in inositol phosphate via specific stimulation of low-abundance high-specificity Gαq-coupled GcgR, with concurrent inhibition of high-abundance low-specificity Gαs-coupled GcgR [152], [186].

Nonetheless, cAMP has been accepted to primarily mediate the relationship between GcgR stimulation and hepatic protein kinase A (PKA) activation of glycogen phosphorylase kinase and additional glycogenolytic/gluconeogenic enzymes, inhibition of glycogen synthase, and effects on CRE-mediated gene expression [86]. Indeed, the presence of cAMP is linked as highly influential for both glucagon and epinephrine-mediated glucose production in hepatocytes [147], [150], [154]. Additionally, the glucose production-lowering effects of berberine and biguanides such as metformin are suggested to result from direct suppression of glucagon-mediated increases in hepatic cAMP production [118], [197], [92]. The capacity for endogenous circulating glucagon to activate hepatic Gαs /cAMP-mediated glucose production is largely reliant on the concentration threshold within the hepatic portal vein (HPV). The threshold concentration for glucagon to particularly stimulate Gαs engagement/activation with the GcgR is > 100 pM, however, the “normal” physiological range of endogenous glucagon concentrations in the HPV is contentious, having been argued to fall within 28–60 pM or 5–500 pM [152], [188]. Nonetheless, HPV glucagon concentrations reach > 100 pM during “non-normal” conditions of high-stress (i.e. intensive exercise) and pharmacological therapy (Fig. 1). This suggests the GcgR-Gαs-cAMP axis to be responsible for generating maximal glycogenolytic and gluconeogenic effects under pharmacological treatment, and thus is a likely mediating pathway of glucagon’s acute enhancement in energy expenditure [102], [152], [188].

Fig. 1.

Physiology of GcgR signaling in response to circulating hepatic portal vein concentrations of Gcg. The threshold for in vivo activation of the GcgR-Gαs-cAMP signaling axis within the liver is reliant on a glucagon (or glucagon analogue) concentration of > 100 pM within the hepatic portal vein (HPV) system [152], [188]. Pharmacological intervention and intensive exercise activate the hepatic GcgR-Gαs-cAMP system by increasing HPV ligand concentration to > 100 pM. Thus, cAMP-mediated signaling acts as the primary mechanism for an acute maximization of hepatic glucose output. However, contention exists as to whether non-acute stimuli of glucose output, such as increases in endogenous glucagon via short-term fasting and starvation, elevate hepatic glucose output via the Gαs-cAMP pathway or if an alternative Gαq-IP3 axis is involved.

Outside of the canonical GcgR-Gαs-cAMP axis, other protein interactors and downstream effectors are known to modulate GcgR-mediated signaling and physiological outcomes. β-arrestins 1 and 2 are ubiquitously expressed and generally known to arrest or desensitize GPCR signaling via direct binding to the GPCR. The GPCR/β-arrestin interaction can result in steric inhibition of G-protein access to the ligand-bound GPCR as well as facilitate clathrin-mediated endocytosis away from the plasma membrane [167]. In line with this, hepatocyte-specific knockout of β-arrestin 2 (βarr2) leads to substantial increases in GcgR signaling with concomitant decreases in GcgR internalization, resulting in approximately 2x greater cAMP and glucose production in glucagon-stimulated primary hepatocytes [198]. In vivo, βarr2 KO mice exhibit impaired glucose tolerance and hyperglycemia, while βarr2 overexpressing mice exhibit significantly lower fasting blood glucose and metabolic protection against diet-induced obesity [198]. Interestingly, in HFD-fed mice, hepatic βarr2 mRNA expression is reduced and may be linked to the obesogenic deficits in countering hyperglycemia and modulating energy expenditure [145], [198].

Receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs) dynamically regulate ligand-induced GPCR functionalities such as receptor trafficking, G-protein signaling, and β-arrestin recruitment, among other aspects. Three distinct RAMPs exist, RAMPs 1–3, and all are evidenced to interact with the GcgR within in vitro over-expression models [111], [165]. RAMP1 and RAMP3 overexpression coincide with significant decreases in maximal Gcg-induced Gαq signaling by − 30% and − 58% respectively [165]. However, RAMP2 seems to be the predominant isoform that interacts with and modifies GcgR activity [106], [187], [33]. RAMP2 expression is shown to negatively modulate maximal inhibitory Gαi recruitment to the GcgR (−40%), enhance maximal glucagon-stimulated cAMP production (2-fold) and potency (10-fold), improve oxyntomodulin-induced maximal cAMP production by 133%, and mediate GcgR binding promiscuity towards GLP-1R agonists when RAMP2 is not expressed [187]. Additionally, the GcgR-RAMP2 interaction decreases stimulated calcium mobilization by approximately 50%, decreases βarr2 recruitment, increases receptor internalization, and enhances endosomal Gαs signaling [116], [27]. However, viral-mediated liver-specific RAMP2 overexpression in mice does not meaningfully impact any metabolic endpoints in both chow and HFD-fed mice [116].

It is known incorporation of Gαs-coupled GPCRs into endosomes and their subsequent intracellular spatial distribution and continued endosomal signaling can influence cAMP accumulation and downstream outcomes [179], [189], [23]. Interestingly, despite the lack of metabolic consequence in hepatocyte RAMP2-overexpressing mice, hepatocyte-specific knockdown of the endosomal protein VPS37a within in vitro and ex vivo settings increases ligand-bound GcgR localization into Gαs accessible endosomes, enhances total Gαs/cAMP signaling, reduces lysosomal targeting, and alters endosomal localization – which when applied in vivo significantly upregulates glucose production and biases hepatic metabolic flux away from fatty acid oxidation [164]. An alternative emphasis on spatial localization of GcgR signaling for the mediation of downstream outcomes is the reliance of maximal hepatic transcriptional upregulation of genes such phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PCK1), the rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis, on the full internalization of the ligand-bound glucagon receptor [21].

Plasma membrane dynamics and composition can be an influential force on GPCR signaling efficacy [24], [26]. For example, the coordinated lateral trafficking of ligand-bound GLP-1 receptors into liquid-ordered plasma membrane nanodomains facilitates maximal intracellular signaling and endocytosis, while plasma membrane alterations via cholesterol depletion reduce GLP-1 receptor hotspot clustering, internalization, and maximal cAMP efficacy [20]. Interestingly, with the GcgR, acute plasma membrane cholesterol depletion via methyl-β-cyclodextrin enhances Gαs/cAMP signaling in vitro [115]. In line with this, mice loaded with a high-cholesterol diet exhibit blunted hyperglycemic responses to glucagon administration – an effect partially reversed by the cholesterol-lowering compound simvastatin [115].

The dynamics of GcgR signaling are complex, multifaceted, and can be modified by interacting factors. Pharmacological strategies within the GcgR system have primarily focused on minimally modifying the native Gcg sequence to allow for native-type GcgR activation while simultaneously improving long-term circulating efficacy. Other approaches to ligand modifications for the GcgR and the GLP-1R have assessed evoking “partial” or “biased” agonism, which are suggested to capitalize on ligand-stimulated partial activation of the signaling system as a whole (partial agonism), or selective engagement and amplification of certain signaling pathways over others within the GPCR signaling milieu (ligand bias) [104].

3. Development of long-acting glucagon receptor mono-agonists

3.1. IUB288

Hyperglycemic attributes have generally diminished therapeutic interest in Gcg for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Additionally, requisites of prolonged storage stability within the context of chronic administration use, and the need for an extended circulating half-life, have also been presented as formidable obstacles. Glucagon has a short circulating half-life (approximately 5–8 min following I.V. administration in humans), and limited/liable stability in solution [141]. The non-optimal stability of glucagon has previously required the need for immediate peptide administration following reconstitution of the lyophilized peptide in acidic solution. This instability is attributed to glucagon’s insolubility in pH neutral aqueous solutions, its temperature dependency, the tendency to form potentially cytotoxic fibrils, and its susceptibility to degradative oxidation and deamidation [132], [29], [60], [71]. Attributable to glucagon’s degradative susceptibility within acidic solutions are the aspartic acid residues liable to hydrolytic cleavage at positions 9, 15, and 21; and possible glutaminyl deamination sites at positions 3, 20, and 24 [122]. Two primary cleavage products resulting from glucagon degradation in acidic conditions are fragments 10–29 and 16–29 [29]. Asp9 and Asp15, which are amino acids that precede both fragments respectively, and as mentioned are susceptible to hydrolytic cleavage, are considered unmodifiable amino acid positions due to incurred loss in potency [29]. To improve solubility and stability of the glucagon peptide, a N28D substitution increase solubility approximately 2-fold and largely prevents degradation within PBS held at 4° and 25 °C through many months. However, the stability of N28D glucagon is limited within exposure to the physiologically relevant temperature of 37 °C [29]. An alternative route of glucagon peptide modification is the addition of the Exendin-4 CEX sequence to the glucagon C-terminal end, which confers long-lasting stability amidst pH and temperature changes. However what the CEX-modified glucagon gained in solution stability, it lost in receptor signaling potency (CRE-luciferase: Glucagon 100%; N28D Glucagon 72%; Glucagon-CEX 56%) and in specificity (GLP-1R/GcgR activity ratio: Glucagon, 1:62; Glucagon-CEX, 1:14) [29], [51]. These attributes position the N28D-modified glucagon as more conducive to glucagon pharmacological research which later led to the development of IUB288, a glucagon analogue with prolonged in vivo circulating half-life in addition to enhanced solution stability. Regarding IUB288 development, a C16 fatty monoacid was attached at a substituted Lys10 within the N28D-modified glucagon sequence to confer albumin binding and reduce renal clearance. Further, four additional amino acids were substituted within the glucagon backbone, one of which includes an aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) substitution at position 2 to protect against dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inactivation (Fig. 2; Table 1) [114], [142], [42]. These modifications establish an IUB288 half-life of approximately 6.3 hrs, with optimized attributes of enhanced solution stability, solubility, and retention of receptor specificity [76]. Together, IUB288 provided a first opportunity to investigate chronic GcgR agonism with a pharmacokinetic profile not dissimilar to that of the GLP-1R mono-agonist Liraglutide.

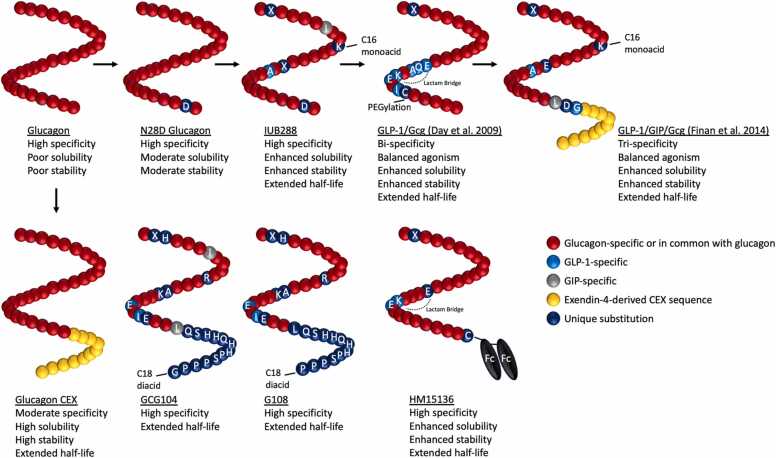

Fig. 2.

Peptide characterization of glucagon-based mono-, dual-, and triple-agonists. Peptide development of glucagon-based agonists from the endogenous sequence, with a focus on peptide stability within solution, solubility, GcgR specificity, and circulating half-life in vivo. Inspirations from these developments and the high sequence homology between glucagon, GLP-1, and GIP, has led to the strategic design of unimolecular GLP-1/Gcg dual-agonists and GLP-1/GIP/Gcg tri-agonists. Complete sequences of each peptide are available within Table 1.

Table 1.

Full one-letter amino acid sequences of Gcg, GLP-1, and GIP, as well as respective GcgR-based mono-, dual-, and tri-agonists.

| Name | Amino Acid Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| Native | Gcg (1–29) | HSQGTFTSDYSKYLDSRRAQDFVQWLMNT |

| GLP-1 (7–36 amide) | HAEGTFTSDVSSYLEGQAAKEFIAWLVKGR | |

| GIP (1–42) | YAEGTFISDYSIAMDKIHQQDFVNWLLAQKGKKNDWKHNITQ | |

| GcgR Agonists | N28D Glucagon | HSQGTFTSDYSKYLDSRRAQDFVQWLMDT |

| IUB288 | HXQGTFISDKSKYLDXRAAQDFVQWLMDT | |

| Gcg CEX | HSQGTFTSDYSKYLDSRRAQDFVQWLMNTGPSSGAPPPS | |

| GCG104 | HXHGTFISDYSRYLDAKRAQEFIEWLLQSHHQHHPSPPPG | |

| G108 | HXHGTFTSDYSRYLDAKRAQEFIEWLLQSHHQHHPSPPP | |

| HM15136 | HXQGTFTSDYSKYLDERRAKEFVQWLMNTC | |

| GLP-1/Gcg (Day et al.) | HXQGTFTSDYSKYLDEQAAKEFICWLMNT | |

| GLP-1/GIP/Gcg (Finan et al.) | HXQGTFTSDKSKYLDERAAQDFVQWLLDGGPSSGAPPPS |

The sufficient improvements in IUB288’s solubility and stability set precedent for effective ready-to-use first aid in combating hypoglycemia. Related to physiological research, IUB288’s improvements in circulating half-life have allowed for greater clarification of the in vivo mechanisms mediating the effects of chronic GcgR agonism within the context of metabolic syndrome. In wild-type (WT) mouse models of diet-induced obesity, despite elevations in ad lib blood glucose, IUB288 substantially reduces body weight (BW) (−25%) and circulating cholesterol (−50%) at 10 nmol/kg over 16 days [76]. Additionally, acute treatment with IUB288 enhances circulating levels of the liver-derived metabolic hormone FGF21 in DIO mice over the course of 12 hrs – an effect also replicated in humans [76]. Both acute and chronic administration of IUB288 induce enhancements in energy expenditure as measured by indirect calorimetry in chow-fed mice, and is similarly reflected as an increase in core temperature in db/db mice [76]. Identified mediators of these IUB288 reductions in body weight are core components of the glucagon signaling system. As such, in various mouse knockout models of the GcgR signaling system, the BW-lowering efficacy of IUB288 treatment is substantially reduced relative to the outcome seen in DIO WT mice; in which: liver GcgR KO mice achieve ∼0–2% of the IUB288-induced BW loss seen in WT, liver FGF21 KO achieve ∼50%, liver farnesoid X receptor KO ∼30%, and CNS β-Klotho KO ∼60% [100], [127]. In addition, knockdown of liver alanine transaminase eliminates the body weight loss effect of IUB288 in chow-fed mice [130].

3.2. GCG104 and G108

Other peptides recently developed to explore the underlying physiology of chronic GcgR agonism are the closely related GCG104 and G108 peptides. GCG104 is developed from the native GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist oxyntomodulin, in which a series of backbone amino acid substitutions, C-terminal amino acid extensions, and a C-terminal C18 acylation reduce intrinsic GLP-1R activity while also enhancing circulating half-life and decreasing renal clearance (Fig. 2; Table 1). GCG104 exhibits potent body-weight lowering effects with daily administration at 7.5 nmole/kg over the course of 12 days, an effect ultimately reliant on whole-body glucagon receptor expression, and more specifically hepatic glucagon receptor expression [80].

G108 shares an almost identical peptide amino acid sequence to that of GCG104, albeit with a glucagon-specific Ile7Thr substitution and removal of the C-terminal glycine (Fig. 2; Table 1). Chronic G108 treatment (7.5 nmole/kg) in DIO mice was used to exemplify the reliance of GcgR-mediated body weight and fat mass loss on the occurrence of systemic hypoaminoacidemia – an effect almost entirely mitigated by a high protein diet during treatment [82]. Interestingly, despite a lack of body weight and fat mass loss in the G108-treated high protein diet group – glucose tolerance, hepatic lipid content, and total cholesterol were significantly improved in comparison to vehicle, indicating potential benefits of glucagon action on systemic metabolic parameters independent of body weight loss [82].

A comparison between the water-soluble glucagon receptor mono-agonist glucagon CEX (Gcg CEX) and the GLP-1 receptor mono-agonist Exendin-4 at 1 μmole/kg/day in DIO mice demonstrates near equivalent degrees of body-weight loss and improvements in glucose metabolism, both without signs of fasting hyperglycemia [122]. Additionally, HM15136, a novel glucagon mono-agonist with an IgG4 Fc fragment conjugated to the C-terminal end, exhibits an enhanced 36 hr half-life, high GcgR specificity, high solution stability, and potent hyperglycemic properties. However, HM15136 has not been trialed in anti-diabetic or anti-obesogenic experiments [78]. HM15136 is currently in a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of congenital hyperinsulinism (NCT04732416).

4. Partial agonism, biased/super agonism, and system bias of glucagon peptide variations

4.1. Partial Agonists

Solubility and stability may not be the only optimizable trait within the glucagon peptide. Notable early glucagon structure-function studies by the Hruby and Merrifield groups identified the importance of the glucagon peptide N-terminus for inducing receptor signaling and the C-terminus for conveying receptor recognition [194], [84]. These findings culminated in the discovery of peptide antagonists that competitively bind the glucagon receptor and simultaneously inhibit cAMP signaling within rat hepatic membranes. The first of these antagonistic peptides were TH-Glucagon, [desHis1, Glu9]glucagon amide, and [desHis1, desPhe6, Glu9]glucagon amide [11], [143], [181], [186], [93].

Amino acid modifications within the Gcg sequence have been utilized to create partial agonists or to bias GcgR action. The functional importance of His1 and its associated α-amino group within the Gcg sequence toward receptor binding and signaling set the foundation for the development of the aforementioned antagonists. Yet, a single substitution of desamino histidine at position 1 within the glucagon backbone ([desHis1]glucagon) does not completely eliminate cAMP signaling [84]. [desHis1]glucagon is one of the first identified partial agonists at the GcgR as quantified via a 50-fold decrease in cAMP production and a 15-fold decrease in receptor binding relative to the native sequence (Epand, 1980; [110]). While peptides with partial agonism properties at the GcgR have not been extensively developed, more recent modifications to the glucagon sequence include stereochemical inversions of Tyr10 or Glu20. As measured by a cAMP responsive element (CRE)-luciferase reporter, [dTyr10]glucagon and [dGlu20]glucagon exhibit moderate partial agonism properties, no substantial loss in potency (81% and 77% to native glucagon, respectively), and no increase in off-target GLP-1R promiscuity [121].

As mentioned previously, Aib substitution at position 2 within the native Gcg sequence confers a degree of proteolytic protection and extends half-life. However, Aib2 inclusion also induces partial agonism at the GcgR as evidenced by an approximate − 46% decrease in Gαs recruitment (as measured by Mini-Gs) and a − 75% reduction in βarr2 recruitment [139]. Interestingly, an additional introduction of a Q3H mutation resulting in [Aib2, His3]glucagon reconstitutes maximal Gαs and βarr2 recruitment to 75% and 53% respectively. The weak partial agonism elicited by [Aib2]glucagon is suggested to be mediated by a differential GcgR conformation related to transmembrane segment 6 and extracellular loops 2 and 3 [139]. An underappreciated element of partial agonism is its potential to explain improvements in effect relative to full agonism within in vivo settings, as has been seen with GLP-1 receptor and μ opioid receptor agonists [70], [94]. Interestingly, when comparing similar GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist sequences that differ in containing either the weak partial agonism-inducing Aib2 substitution, or the strong partial agonism-inducing substitutions of Aib2 and His3, the weak partial agonist [Aib2] exhibits superior and prolonged reductions in glycemic excursions and food intake relative to [Aib2, His3]. A GcgR-centric partial agonism interpretation of this in vivo comparison is however complicated by a differential − 40% reduction in maximal GLP-1R-specific βarr2 recruitment by the [Aib2] dual GLP-1R/GcgR agonist [139].

4.2. Ligand bias and super agonists

Certain sequence modifications to the glucagon peptide have indicated potential for evoking physiological super-efficacy through intracellular biased signaling as indicated by in vitro assays. Within acute exposure settings, glucagon analogues formed by substitutions of dHis1, Phe1, Gly2, or dGln3, exhibit reduced ligand cAMP potency, yet retain maximal cAMP efficacy [95]. Interestingly, these particular ligands also simultaneously exhibit an acute 15–57% decrease in maximal efficacy for βarr2 recruitment [95]. One of the primary functions of β-arrestin is to inhibit continued G-protein signaling. Therefore it is possible that the combination of retained maximal cAMP efficacy with paralleled reductions in maximal βarr2 efficacy may facilitate a degree of super-agonism at high enough concentrations over a prolonged period of time. However, translation of these in vitro effects into in vivo outcomes has not yet been examined further [95]. Interestingly, in line with the described acute cAMP/βarr2 dynamics, 16 hr stimulation of Huh7 cells with the aforementioned ligands enhances maximal cAMP efficacy by 18–21% relative to native glucagon, while [Phe1]glucagon and [dGln3]glucagon additionally improve potency. These enhancements in 16 hr cAMP accumulation may reflect prolonged receptor activity due to potential reductions in sustained βarr2 recruitment. These results however did not translate to significant in vitro increases in cAMP-responsive glucose-6-phosphatase upregulation or glucose production [95].

Super-glucagon modifications have also been assessed in vivo for capacity to acutely induce hepatic glucose production in anaesthetized rats. An early study of [dPhe4]glucagon demonstrates a 655% improvement in hepatic glucose production potency over that of native glucagon during a 2-hr span [172]. Additionally, within an immediate time frame, [dPhe4]glucagon stimulates an approximate 25% increase in blood glucose relative to native glucagon just 20 min after 0.5 μg ligand administration [172]. These results have been further expanded on with [dPhe4, Phe25, Leu27]glucagon-amide and [dSer2, dPhe4, Phe25, Leu27]glucagon-amide, both of which improve potency for stimulating glucose production by 768%, and 527% relative to native glucagon [125]. These enhancements in glucose production seen with [dPhe4]glucagon may be mediated by its 4-fold increase in cAMP potency and 1.5-fold increase in GcgR affinity relative to native glucagon within rat hepatic membranes [149]. Together, it is possible that a dPhe4 modification within the glucagon peptide sequence confers attributes of GcgR super-agonism, however this has not yet been extensively validated to be independent of possible enhancement in circulating half-life [125], [172], [38].

4.3. Potential for system bias

System bias is described as differential ligand-induced outcomes not mediated by changes in the ligand itself, but rather by the availability/dynamics of non-ligand molecules across tissues, such as differences in the stoichiometry of receptors and downstream modulatory proteins or effectors [104]. The primary drawbacks of pharmacological glucagon therapy for metabolic syndrome, aside from hyperglycemia, are hemodynamic properties that include effects of increased heart rate and cardiac contractility [138]. Indeed, it does seem that glucagon has direct action at glucagon receptors located within the cardiac membrane [117], [6], [79]. Interestingly, earlier evidence shows certain modifications to the glucagon sequence result in differential potency and efficacy preferences at the GcgR within rat hepatic membranes (h.m) over cardiac membranes (c.m). For example, when assessing maximal cAMP efficacy as (h.m/c.m.) relative to native glucagon (100%/100%), [dGln3]glucagon (85%/30%) demonstrates preference for the hepatic GcgR while retaining 75% in vivo glycogenolytic activity [149]. It may be possible, to some extent, to modify the glucagon peptide sequence for differential responses across tissues, however this has yet to be explored further.

5. Development of GLP-1R/GcgR unimolecular dual-agonists

5.1. Co-administration of GLP-1 and glucagon

As mentioned, enhancements in energy expenditure and reductions in food intake position glucagon pharmacology as a potentially valuable treatment for metabolic syndrome, however its hyperglycemic liability has made practical implementation non-existent [102], [161], [3], [30], [85]. A peptide co-administration approach has provided opportunity to counter-balance glucagon-induced hyperglycemia with the glucose-dependent insulinotropic effects of GLP-1 receptor co-agonism. Co-administration of glucagon with GLP-1 preserves the energy expenditure effects of glucagon while nearly eliminating the net hyperglycemic excursion in both mice and humans [175]. Due to the overlapping effects of glucagon and GLP-1 in eliciting food intake reductions, co-administration in humans synergistically reduces food intake thus allowing for lower-dosing of GLP-1 [28]. In line with this, greater acute food intake reduction in mice following peripheral co-administration of GLP-1 and glucagon is associated with greater c-fos induction in the area postrema and central nucleus of the amygdala relative to saline or mono-treatment controls [134]. The metabolic benefits associated with acute co-administration seem to also apply within chronic administration, as DIO non-human primates exhibit significant enhancements in body weight loss during chronic Gcg and GLP-1 co-administration relative to either treatment alone [48]. Therefore, synergistic co-agonism at the GLP-1R and GcgR allows for enhancements in glucose clearance, body weight loss, and satiety, while retaining the energy expenditure effects attributable to GcgR agonism, thus expanding therapeutic functionality.

5.2. Pre-clinical unimolecular GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists

In 2009, research towards unifying GcgR and GLP-1R co-agonism properties into a single non-conjugated unimolecular peptide took its first steps. Two strategies were employed to achieve this, the first centered around synthetically engineering GLP-1R agonism into a glucagon core sequence, while the other focused on protracting the half-life of oxyntomodulin via a DPP-IV-resistant dSer2 substitution and cholesterol linkage (DualAG) [140], [43]. Within the first strategy, the DiMarchi and Tschöp laboratories utilized high sequence homology between Gcg and GLP-1 to iteratively develop a balanced chimeric dual-agonist with a single pharmacokinetic profile (Fig. 2; Table 1) [43]. Regarding synthesis of this unimolecular dual-agonist, as Gcg amino acid positions 3, 10, and 12 are of critical importance to GcgR activation, and as the N-terminal sequences of both Gcg and GLP-1 have capacity to bind the GLP-1R, the first 15 amino acids of the Gcg base sequence were left unmodified. However, with utilizing an unmodified N-terminal Gcg sequence, challenges remain in achieving balanced affinity at the Gcg and GLP-1 receptors. Specificity to the GcgR and GLP-1R is largely determined by the ligand’s C-terminal sequence interaction with the receptor’s N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) [155]. Therefore, improvements in GLP-1R specificity were engineered into the last 14 amino acid stretch of the Gcg sequence via C-terminal amidation and the substitution of six GLP-1-specific amino acids. Together, these modifications created an imbalance favoring GLP-1R superiority over GcgR due to the enhanced GLP-1R ECD recognition and helical stability. To recover GcgR activity, the introduction of a lactam bridge between Glu16 and Lys20 promoted secondary structure stabilization and balanced GLP-1R/GcgR activity. Lastly, a Cys24 PEGylation site enhanced circulating half-life and reduced renal clearance [43]. With these modifications, a long-acting balanced GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist was achieved (Table 2). Pre-clinical experiments in DIO mice using this dual-agonist evidence greater weight lowering effects, food intake reductions, enhancements in energy expenditure, improvements in glycemic control, and reductions in hepatic steatosis, plasma cholesterol and triglycerides, all relative to the vehicle and a matched non-lactam bridge-containing (GLP-1R preferring) control peptide [43]. The unimolecular composition of GLP-1R-mediated anti-hyperglycemic effects with retention of GcgR-mediated enhancements in lipolysis and energy expenditure was a first proof-of-principle for synthetic implementation of balanced GLP-1R agonism into a glucagon core sequence.

Table 2.

Up-to-date clinical trials of respective GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists and GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR tri-agonists, with the farthest advanced trials relevant to diabetes and obesity noted. Relevant pharmacological comparators and Trial ID (www.clinicaltrials.gov) included.

| Name | Targets | Most Advanced Clinical Trials | Relevant Comparators | Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDI0382 (Cotadutide) | GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase II (Diabetes) Phase II (Diabetes) Phase II (Diabetes/Obesity) |

Dosage; Placebo; Semaglutide Placebo; Liraglutide Dosage; Placebo; Liraglutide |

NCT04515849 NCT03555994 NCT03235050 |

| SAR425899 | GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase I (Diabetes) Phase II (Diabetes) |

Dosage; Placebo; Dosage; Placebo; Liraglutide |

NCT02411825 NCT02973321 |

| JNJ-64565111 / HM12525A (Efinopegdutide) |

GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase II (Diabetes/Obesity) Phase II (Obesity) |

Dosage; Placebo Dosage; Placebo; Liraglutide |

NCT03586830 NCT03486392 |

| IBI362 / LY3305677 (Mazdutide) |

GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase III; on-going (Diabetes) Phase III; on-going (Obesity) Phase II (Diabetes) |

Dosage; Placebo Dosage; Placebo Dosage; Placebo; Dulaglutide |

NCT05628311 NCT05607680 NCT04466904 |

| BI456906 | GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase II (Diabetes) Phase II (Obesity) |

Dosage; Placebo; Semaglutide Dosage; Placebo |

NCT04153929 NCT04667377 |

| NNC9204–1777 | GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase I (Obesity) Phase I (Obesity) |

Placebo Dosage; Placebo |

NCT02941042 NCT03308721 |

| ALT-801 (Pemvidutide) | GLP-1R/GcgR | Phase II (Obesity) Phase I (Diabetes/NAFLD) |

Dosage; Placebo Dosage; Placebo |

NCT05295875 NCT05006885 |

| LY3437943 | GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR | Phase II (Diabetes) Phase II (Obesity) |

Dosage; Placebo; Dulaglutide Dosage; Placebo |

NCT04867785 NCT04881760 |

| HM15211 | GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR | Phase II; on-going (NAFLD) Phase I (Obesity) Phase I (NAFLD/Obesity) |

Placebo Dosage; Placebo Dosage; Placebo |

NCT04505436 NCT03374241 NCT03744182 |

| SAR441255 | GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR | Phase I (Overweight) | Placebo | NCT04521738 |

The 37 amino acid oxyntomodulin (OXM) is an endogenous peptidic hormone with demonstrable activity at both the Gcg an GLP-1 receptors. Secreted from intestinal L cells as a product of post-translational processing of the 160 amino acid proglucagon, oxyntomodulin contains the full glucagon amino acid sequence followed by an 8 amino acid C-terminal extension [120], [13], [14]. Radiolabeled receptor binding assays show oxyntomodulin binds to the GLP-1R with an approximate 10-fold reduction in potency relative to native GLP-1, with a comparative 100-fold reduction in cAMP potency, indicating the extent of oxyntomodulin’s 8 amino acid C-terminal extension in conferring additional promiscuity at the GLP-1R [41]. At the glucagon receptor, oxyntomodulin exhibits a 10-fold decrease in receptor binding potency relative to native glucagon, with an approximate 50–100-fold relative decrease in cAMP potency [12], [41].

Both chronic ICV and peripheral administration of oxyntomodulin in rats demonstrate prominent reductions in food intake, an effect suggested to be likely GLP-1R-dependent. However, oxyntomodulin also exhibits superior body weight loss relative to pair-fed controls, indicating a complimentary enhancements in energy expenditure likely attributable to co-GcgR agonism [39], [40]. These effects seem to translate from rodent to humans as acute treatment with oxyntomodulin decreases caloric intake in healthy subjects, while chronic administration reduces both energy intake and body weight in overweight individuals [192], [34]. Despite the previously noted effects of glucagon on food intake, the anorectic effects of oxyntomodulin seem to be primarily mediated by the presence of the GLP-1R, as confirmed by lack of food intake reduction in GLP-1R knockout mice [168]. Nonetheless, oxyntomodulin continues to increase intrinsic heart rate in GLP-1R knockout mice indicative of GcgR-mediated activity [168]. Similarly, in a head-to-head comparison between oxyntomodulin and Q3E-modified oxyntomodulin (OXMQ3E), which is an oxyntomodulin-based GLP-1R mono-agonist control, both peptides similarly reduce food intake yet only oxyntomodulin elicits a greater degree of weight loss. This provides further evidence of an energy expenditure component in oxyntomodulin [105], [163].

The aforementioned second strategy for developing a unimolecular GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist, which is the half-life protracted oxyntomodulin-based DualAG, demonstrates superior body weight and food intake reductions to that of a matched GLP-1R mono-agonist control (GLPAG) in WT mice [140]. The body weight lowering efficacy of DualAG is reliant on the presence of both GcgR and GLP-1R, and is highlighted in knockout mouse lines of each respective receptor. Within both GLP-1R and GcgR knockout lines, DualAG elicits approximately 50% of the body weight loss achieved to that in WT mice, indicating an approximate balance in receptor contribution to body weight loss occurring after 5 days of treatment [140].

Since 2009, a variety of new GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist peptides have been trialed in pre-clinical settings. As a basis, the GLP-1R/GcgR cAMP activity ratio of the native glucagon peptide is approximately 1:62. Simply adding the 10 amino acid exendin-4-derived CEX sequence to native glucagon (glucagon-CEX) improves the GLP-1R/GcgR activity ratio to 1:14 [29], [51]. Comparisons between DPP-IV protected [dSer2]glucagon and [dSer2]glucagon-CEX within mice at 25 nmole/kg i.p. demonstrates the ability of [dSer2]glucagon-CEX to stimulate a 100–150% increase in acute insulin secretion relative to the non-CEX-extended glucagon in a GLP-1R-dependent manner, ultimately mitigating acute GcgR-induced glucose excursion [112].

Alternatively, the GLP-1R mono-agonist exendin-4 has no measurable cAMP activity at the GcgR. However, the simple substitution of Ser2 and Gln3 within the exendin-4 sequence achieves single-digit nanomolar potency for GcgR cAMP without negatively influencing GLP-1R potency [51]. With this basis, a rationally designed long-acting exendin-4/Gcg dual agonist (peptide 14) was developed and is composed of the aforementioned substitutions within the Exendin-4 sequence, a Lys16 substitution to allow for C16 fatty acid acylation, and additional amino acid substitutions within the exendin-4 backbone to balance GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonism as confirmed by a cAMP activity ratio of approximately 1:1. When comparing peptide 14 to equimolar dosing of the GLP-1R mono-agonist liraglutide, which exhibits similar mGLP-1R cAMP potency and half-life, peptide 14 approximately doubled (−30%) body weight loss relative to liraglutide (−15%) over 32 days in DIO mice. Additionally, both peptide 14 and liraglutide were shown to similarly prevent a 1.5% increase in Hba1c relative to the vehicle over the course of 32 days in db/db mice [51].

5.3. Clinical evidence with unimolecular GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists

Clinical research into the benefits and drawbacks of hybridized unimolecular GLP-1/Glucagon dual-agonists has escalated in recent time. Cotadutide, also known as MEDI0382, was developed in 2016, and in 2018 was the first clinically trialed of the GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists [7], [77], [8]. MEDI0382 contains the native glucagon sequence through the first 9 amino acids, a Lys10 substitution to confer palmitic acid acylation and half-life extension, and additional amino acid substitutions within the glucagon sequence to confer GLP-1R/GcgR co-agonism and proteolytic protection, in particular: K12E, R17E, M27E, N28A, and the addition of Gly30 [77]. Indeed, it has been found that dipeptide proteolytic inactivation of Arg17-Arg18, the oxidative metabolisms of Met27, and the deamidation of Asn28, are all potential sites for in vivo susceptibility to glucagon inactivation [133]. Additionally, MEDI0382 is suggested to have a 5:1 GLP-1R/GcgR cAMP potency preference as measured in vitro [83]. In a phase I study in healthy subjects, the MEDI0382 adverse-effect profile was not unlike the GLP-1R mono-agonist liraglutide, in which dose-escalation is correlated with vomiting, nausea, dizziness, and slight increases in heart rate. Dose-dependent effects were observed on reductions in peak glucose levels and food intake over the course of multiple meals within one day. The highest dosage (300 μg) demonstrated a 76.6% reduction in food intake albeit with a high incidence of adverse effects (83.3% of subjects), while 100 μg exhibited a 17.8% reduction in food take with a 33.3% occurrence of adverse effects [8]. In a once-daily multiple ascending dose phase Ib clinical trial and a 41-day phase IIa trial in overweight and type 2 diabetic patients, general safety and tolerability of MEDI0382 were established, as well as placebo-corrected efficacy in reducing fasting blood glucose (−1.7 mmol/L), post-prandial glucose excursions following a mixed meal test (−22.6% AUC0–4 h), body weight (−2.1 kg), and liver fat (−19.6%) [7]. In particular, the improvements seen with MEDI0382 treatment in glucose excursion following the mixed meal test were further delineated in another phase IIa study over 49 days. The enhanced reductions in post-prandial glucose excursion by MEDI0382 are suggested to be mediated via enhanced insulin secretion and delayed gastric emptying [135]. Relative to daily injections of the GLP-1R mono-agonist control liraglutide (1.8 mg), both MEDI0382 dosages at 100 μg and 200 μg decrease body weight to an approximately equal degree over the course of 54 weeks. However the number of subjects that experienced adverse effects leading to study discontinuation were approximately 5x and 20x higher than that of liraglutide, respectively. Nonetheless, the 100 μg and 200 μg dosages of MEDI0382 also led to slight improvements in total cholesterol (−2.57% at 100 μg and −3.67% at 200 μg, relative to liraglutide) and total triglycerides (−3.61% at 100 μg and −6.11% at 200 μg, relative to liraglutide), although these changes were not significant [126].

Since the development of Cotadutide, the field of available GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists has expanded, with clinical studies providing mixed results. The GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist SAR425899 (Sanofi) underwent a phase I single and multiple ascending dose clinical trial with daily subcutaneous administration in both healthy/overweight subjects and overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Over the course of 21–28 days, SAR425899 evidences maximal BW reduction of 5.32 kg in healthy/overweight patients, while overweight/obese patients with T2D experienced maximal BW reductions of 5.46 kg along with significant reductions in fasting plasma glucose and glycated hemoglobin [177]. Proof of dual-receptor engagement for SAR425899 was assessed in humans with positron emission tomography, in which SAR425899 evidences strong engagement with the GLP-1R, yet lacked clear occupancy at the GcgR [50]. To demonstrate the effects of SAR425899 on a calculated outcome of β-cell functionality, a group of 36 obese patients with type 2 diabetes were given either placebo or a low- or high-dose escalation of SAR425899 over the course of 28 days which demonstrated improvements of 23% (placebo), 163%, and 95% respectively [184]. However, SAR425899 was discontinued in Phase II clinical trials due to the high occurrence of gastrointestinal adverse events in subjects.

Efinopegdutide (also known as MK-6024, JNJ-64565111, and HM12525A) in T2D obese patients, with effects as early as 12 weeks under 5.0 mg, 7.4 mg, and 10 mg once-weekly treatment, achieves significant placebo-subtracted BW reductions of − 4.6%, − 5.9% and − 7.2% respectively without significant changes in HbA1C% or fasting insulin and glucose [44]. Additionally, a longer course of 26 weeks Efinopegdutide (5.0, 7.4 or 10.0 mg) treatment in non-diabetic obese patients demonstrates significant placebo-corrected body weight reductions of − 6.7%, − 8.1%, and - 10.0%, relative to − 5.8% of the active comparator Liraglutide (3 mg) [4]. However patient discontinuation due to adverse effects from treatment was between 18% and 32% for all Efinopegdutide doses, and 17% for Liraglutide [4]. Despite discontinuation towards the therapeutic indications of obesity and T2D, Efinopegdutide is currently being assessed for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

A phase I clinical trial of once-weekly Mazdutide (also known as IBI362 or LY3305677) with dose-escalation over 12 weeks demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in overweight and obese patients, reducing body weight by − 4.8% (3 mg dosage), − 6.4% (4.5 mg), and − 6.0% (6 mg) [90]. No participants discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Gastrointestinal adverse events were commonly reported but mild in severity, while three patients experienced asymptomatic cardiac disorders [90]. When compared to 1.5 mg dulaglutide (a GLP-1R mono-agonist), both 4.5 mg and 6 mg dosages of Mazdutide achieve similar reductions to dulaglutide in fasting glucose and HbA1c over the course of 12 weeks, but stimulate significantly greater body weight loss [91]. Dosages as high as 9 mg and 10 mg of Mazdutide were trialed and generally well-tolerated with no serious adverse events, achieving a respective placebo-corrected body weight loss of − 9.8% and − 6.2% in overweight or obese Chinese adults [89].

The GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist BI 456906 developed by Boehringer-Ingelheim achieves body weight reductions of − 5.8% over 6 weeks and − 13.8% over 16 weeks, at the maximal dosages within a multiple rising dose phase Ib clinical study [96]. Patient discontinuation was at 12.5% (6 weeks) and 17.8% (16 weeks) due to the occurrence of gastrointestinal, vascular, or cardiac adverse effects. Reductions in plasma amino acids and glucagon were suggested to indicate successful GcgR and GLP-1R targeting [96].

Similarly, 12.6% body weight loss is achieved in obese patients over the course of 12 weeks with NNC9204–1777 (Novo Nordisk) in a multiple ascending dose phase I clinical trial. However, due to dose-dependent increases in heart rate and reductions in reticulocyte count, increases in markers of inflammation and hepatic disturbances, and impaired glucose tolerance at the highest dosages, conclusions of unacceptable safety concerns have been stated [63].

Other GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists, such as Pemvidutide (also known as ALT-801,) are also documented as undergoing clinical trials in which data has yet to be reported.

6. Development of GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonists

6.1. Pre-clinical unimolecular GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonists

In additional to the development and clinical evaluations of the novel GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists, GLP-1R/gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) receptor dual-agonists have experienced profound success in the treatment of T2D and obesity [128], [159], [18]. Tirzepatide (Eli Lilly), a GIPR-favoring GLP-1R/GIPR dual-agonist, has recently been approved for the indication of T2D by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and is currently on U.S. FDA Fast Track designation for the treatment of obesity with associated comorbidities. Similar to the GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists, the GLP-1R/GIPR dual-agonists are chimeric unimolecular peptides possessing specific amino acid residues from both GLP-1 and GIP to confer bi-specific receptor activation. Combining GLP-1 and GIP receptor agonism endows synergistic effects in both insulinotropic and satiety endpoints [195], [55].

Due to the success of both dual-agonistic approaches, and the general high sequence homology between GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon, the next step in novel pharmaceutical development was the design of chimeric GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR unimolecular triple-agonists [103], [178]. In 2014, through iterative chemical refinement, a balanced high-potency triple-agonist for the GLP-1R, GIPR, and GcgR was developed [56]. This particular tri-agonist was developed from the GLP-1/Gcg dual-agonist core sequence previously described, however without the lactam bridge [43]. With removal of the lactam bridge and an aminoisobutyric acid substitution at position 2, the dual-agonist preferentially targets the GLP-1R and GIPR, and loses potency at the GcgR. Therefore, additional substitutions of Lys10 (for C16 acylation), Glu16 (for hydrolytic stability), Arg17 (Gcg-specific), Gln20 (GIP/Gcg-specific), Leu27 (GIP-specific), Asp28 (for solubility), and the addition of the Exendin-4 CEX tail, together established balanced affinity between all three receptors and served auxiliary functions to enhance chemical stability, solubility, and secondary structure (Table 2). In DIO mouse models, this GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonist demonstrates profound efficacy through synergism between the GcgR to increases energy expenditure, the GLP-1R to induce satiety and improve glucose control, and GIPR to potentiate the insulinotropic and satiety inducing effects [56]. Through various knockout models, pharmacological blockades, and cryo-EM imaging of the triple-agonist-bound to the GIPR, GLP-1R and GcgR receptors in complex with Gαs, validated proof-of-principle for a high-potency unimolecular tri-agonist was established [196], [56].

6.2. Clinical unimolecular GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonists

Three GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonists have surpassed pre-clinical testing and have entered clinical trials, and these are LY3437943 (Eli Lilly), HM15211 (Hanmi Pharmaceutical), and SAR441255 (Sanofi). LY3437943 is a C20-diacid acylated compound that favors GIPR activity albeit with balanced activity between GLP-1R and GcgR in vitro. LY3437943 exhibits a safety and tolerability profile similar to that of other GLP-1R mono-agonists, which includes a slight increase in heart rate [37]. A first-in-human phase Ia clinical trial has reported that a single dose of LY3437943 produced comparable body weight loss to that of four weeks of weekly injections of Tirzepatide, an effect that extends past the LY3437943 six day half-life exposure and absent in similarly designed single dose studies with GLP-1R mono-agonists [36], [37], [46]. A phase Ib multiple ascending dose trial of LY3437943 has further confirmed the potent reductions in blood glucose and body weight, while retaining an acceptable tolerability and safety profile over 12 weeks of treatment [182].

HM15211, another GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR tri-agonist peptide, is alternatively attached to a human Fc fragment for improved half-life extension and once weekly administration. Phase Ia and Ib studies have demonstrated efficacy for HM15211 in reducing both liver fat and body weight in obese subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and is currently in phase II trials for the targeted treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [1], [107].

SAR441255, a recently developed triple-agonist based on the exendin-4 sequence, demonstrates improved glycemic control in healthy human subjects following a mixed meal test in a phase Ia single dose clinical trial. Additionally, SAR441255 exhibits extensive improvements in body weight and glycemic control in diabetic obese monkeys. Positron emission tomography validated high GLP-1R and GcgR engagement with SAR441255 in lean monkeys, however GIPR engagement was reported to not be effectively assessed due to a lack of a suitable radiotracer [17].

GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonists are still early in the developmental process, as addressing potential safety concerns and further clinical trials are needed [123]. However the enhanced efficacy of these tri-agonist chimeric peptides over that of dual-agonists in pre-clinical and clinical studies have validated the conceptual approach to maximizing anti-obesogenic and anti-diabetic outcomes.

7. Glucagon receptor targeting as a tool for small molecule delivery

Glucagon receptor agonism is not only restricted to anti-diabetic/anti-obesogenic potential, but also is valualbe for small molecule targeting into GcgR-expressing tissues. Small molecule nuclear hormones exhibit profound effects on systemic metabolism. However, pharmacological therapy with these hormones and the near ubiquitous tissue targeting can lead to undesirable off-target effects thus limiting utility [124], [166]. Peptides can act as tissue-specific targeting agents to introduce DNA, antisense nucleic acids, oligonucleotides and small molecules into the intracellular space [162]. In particular, the chemical conjugation of small nuclear hormones to the C-terminal end of glucagon allows for the predominant targeted delivery into hepatic tissue. The liver is a central component to systemic energy homeostasis, and pharmacologically targeting the hepatic state has been linked to beneficial outcomes on systemic health parameters [16], [88]. The principle behind a peptide-nuclear hormone conjugate is that the targeting peptide binds to its cognate receptor, which then subsequently undergoes internalization bringing in the nuclear hormone cargo with it [18]. Once the peptide-nuclear hormone conjugate enters into the intracellular endolysosomal pathway, it is hypothesized that pH-dependent proteases cleave and liberate the nuclear hormone away from the peptide, allowing nuclear activation and reprogramming to occur (Fig. 3) [156], [176], [57].

Fig. 3.

: The Glucagon/T3 peptide-nuclear hormone conjugate. (Top left) A glucagon/T3 conjugate (Gcg/T3), developed in 2016, is comprised of a DPP-IV-resistant [dSer2]glucagon peptide sequence with an Exendin-4-derived CEX tail, conjugated to T3 via a C-terminal lysine and gamma glutamic acid spacer [54]. (Bottom left) The primary sites of pharmacological synergistic action between GcgR agonism and T3 action are the liver and white adipocytes. (Right) At the respective tissues, following Gcg/T3 binding to the GcgR, the receptor is internalized, in which trafficking of the ligand-GcgR complex through the endolysosomal system is suggested to ultimately end with pH-dependent proteolytic cleavage and liberation of the T3 molecule for nuclear activation.

Triiodothyronine (T3) increases fatty acid oxidation and energy expenditure, influences cholesterol metabolism, but however has off-target effects of cardiac hypertrophy and tachycardia, as well as systemic muscle wasting and bone resorption [144], [153], [157], [160], [45]. The glucagon receptor is known to rapidly internalize into the intracellular space following glucagon stimulation, with a fraction entering into the acidic late endosome/lysosomal pathway [10], [164], [21]. Therefore, a DPP-IV resistant glucagon was conjugated with T3 (Gcg/T3) via a gamma-glutamic acid linker to target GcgR-expressing hepatic and white adipose tissue [54]. The potency and maximal efficacy of Gcg/T3 at the GcgR, as measured by cAMP, is validated to be comparable to both the DPP-IV protected Gcg analogue and the native glucagon sequence. Proof-of-principle for effective hormone delivery with the Gcg/T3 is confirmed by the induction T3 responsive genes in the hepatic cell line HepG2. In vivo Gcg/T3 administration is shown to reduce body weight and improve glycemic control in a dose-dependent manner, as well as improve symptoms of NASH [54]. Interestingly, the hepatic effects of targeted T3 exposure seem to also mitigate the hyperglycemic effect of glucagon. Importantly, in DIO mice, the Gcg/T3 conjugate leads to substantial T3 accumulation in the liver which results in: a reduction of plasma cholesterol to same degree of that elicited by free T3, a reduction of hepatic cholesterol greater than that of glucagon or free T3, and an absence of free T3-mediated increases in food intake and locomotion – all while retaining additional enhancements in energy expenditure associated with systemic T3 agonism [54]. Further validation of the proposed mechanism was emphasized with absence of Gcg/T3-mediated effects in global GcgR knockout mice and mice with a liver-specific deletion of thyroid hormone receptor B [54]. In short, the primary benefits of systemic T3 pharmacology are recapitulated with glucagon-targeted delivery of T3 into the liver, leading to enhanced liver-localized metabolic benefits without the free T3-mediated increases in food intake or off-target adverse effects.

8. Concluding remarks

The unique pharmacology of glucagon has repositioned the peptide as not only an acute hyperglycemic agent, but paradoxically, a potent chronic anti-diabetic and anti-obesogenic therapy. Glucagon agonism possesses satiety-inducing and energy expenditure-enhancing attributes that involve actions within the brain, sympathetic tone, and hepatic substrate processing. As the potential for glucagon pharmacotherapy has become more prominent, long-acting glucagon analogues have been engineered to further explore the effects of chronic glucagon receptor agonism. The long-acting IUB288 glucagon analogue has been used to identify GcgR-mediated: reductions in body weight, food intake, and circulating cholesterol; increases in energy expenditure and hepatic FGF21 production; and reliance on liver GcgR, liver FGF21, liver farnesoid X receptor, CNS β-Klotho and liver alanine transaminase for the metabolically beneficial effects of chronic GcgR agonism [100], [127], [130], [76]. The GCG104 and G108 peptides have also been developed, with G108 emphasizing the occurrence of systemic hypoaminoacidemia in mediating GcgR-induced body weight loss, as well as demonstrating the BW loss-independent improvements in insulin-sensitization during concomitant GcgR agonism and high protein diet supplementation [80], [82]. Additionally, finer nuanced attributes that can be applied to GcgR mono-agonists such as partial agonism, super agonism, and tissue-biases have yet to be fully explored in the context of chronic treatment and body weight loss, and may underlie untapped potential.

Pre-clinical developments of chimeric unimolecular peptides consisting of GLP-1 and glucagon-specific amino acids have provided a synergistic strategy in combining the insulinotropic and satiety-inducing effects of GLP-1 with the energy expenditure effects of glucagon. Since preclinical development, multiple GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonists have progressed to phase I and phase II clinical trials and found success in treating patients with type 2 diabetes, obesity, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Similarly, the GLP-1R/GIPR/GcgR triple-agonists in phase I clinical trials represent a promising horizon of therapeutic utility, in which the body weight-lowering and glycemia-correcting synergies associated with simultaneous agonism of all three receptors seem to outpace the benefits of the well-developed GLP-1R/GIPR dual-agonists. However, much remains to be seen in terms of optimization of the triple-agonists, which includes strategically customizing ideal receptor activity ratios and limiting adverse events.

Non-traditional routes of glucagon receptor pharmacology include the hepatic targeting of small molecules or nuclear hormones as is seen with the non-hyperglycemic glucagon-T3 conjugate [54]. The liver remains a central part of not only the energy expenditure component of glucagon, but of also mediating systemic metabolic parameters including risk for insulin insensitivity, atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, and other attributes leading to progressive systems deterioration. The future likely holds opportunity for further development of glucagon-mediated hepatic targeting, as synergism between glucagon agonism and the small molecule of choice is likely greater than that of the individual components alone. However, the road to clinical establishment will likely be difficult due to the increased complexity and higher risk.

Acknowledgements

This work was co-funded by the European Research Council (ERC) within the ERC CoG Trusted no.101044445 awarded to TDM. TDM further received funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG TRR296, TRR152, SFB1123 and GRK 2816/1), and the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD e.V.).

Contributor Information

Aaron Novikoff, Email: aaron.novikoff@helmholtz-munich.de.

Timo D. Müller, Email: timodirk.muller@helmholtz-munich.de.

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Abdelmalek, M., Choi, J., Kim, Y., Seo, K., Hompesch, M., and Baek, S. (2021). HM15211, a novel GLP-1/GIP/Glucagon triple-receptor co-agonist significantly reduces liver fat and body weight in obese subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A Phase 1b/2a, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Poster Presentation.

- 2.Ahrén B., Yamada Y., Seino Y. The mediation by GLP-1 receptors of glucagon-induced insulin secretion revisited in GLP-1 receptor knockout mice. Peptides. 2021;135 doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2020.170434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Massadi O., Fernø J., Diéguez C., Nogueiras R., Quiñones M. Glucagon control on food intake and energy balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019:20. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alba M., Yee J., Frustaci M.E., Samtani M.N., Fleck P. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1/glucagon receptor co-agonist JNJ-64565111 in individuals with obesity without type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized dose-ranging study. Clin. Obes. 2021;11 doi: 10.1111/cob.12432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali S., Drucker D.J. Benefits and limitations of reducing glucagon action for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. -Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;296:E415–E421. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90887.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali S., Ussher J.R., Baggio L.L., Kabir M.G., Charron M.J., Ilkayeva O., Newgard C.B., Drucker D.J. Cardiomyocyte glucagon receptor signaling modulates outcomes in mice with experimental myocardial infarction. Mol. Metab. 2015;4:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambery P., Parker V.E., Stumvoll M., Posch M.G., Heise T., Plum-Moerschel L., Tsai L.F., Robertson D., Jain M., Petrone M., et al. MEDI0382, a GLP-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist, in obese or overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, ascending dose and phase 2a study. Lancet. 2018;391:2607–2618. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambery P.D., Klammt S., Posch M.G., Petrone M., Pu W., Rondinone C., Jermutus L., Hirshberg B. MEDI0382, a GLP-1/glucagon receptor dual agonist, meets safety and tolerability endpoints in a single-dose, healthy-subject, randomized, Phase 1 study. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018;84:2325–2335. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Authier F., Desbuquois B. Glucagon receptors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.: CMLS. 2008;65:1880–1899. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7479-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Authier F., Desbuquois B., De Galle B. Ligand-mediated internalization of glucagon receptors in intact rat liver. Endocrinology. 1992;131:447–457. doi: 10.1210/en.131.1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizeh B.Y., Ahn J.-M., Caspari R., Shenderovich M.D., Trivedi D., Hruby V.J. The role of phenylalanine at position 6 in glucagon's mechanism of biological action: multiple replacement analogues of glucagon. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:2555–2562. doi: 10.1021/jm960800d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldissera F.G., Holst J.J., Knuhtsen S., Hilsted L., Nielsen O.V. Oxyntomodulin (glicentin-(33-69)): pharmacokinetics, binding to liver cell membranes, effects on isolated perfused pig pancreas, and secretion from isolated perfused lower small intestine of pigs. Regul. Pept. 1988;21:151–166. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(88)90099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bataille D., Coudray A.M., Carlqvist M., Rosselin G., Mutt V. Isolation of glucagon-37 (bioactive enteroglucagon/oxyntomodulin) from porcine jejuno-ileum. Isolation of the peptide. FEBS Lett. 1982;146:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bataille D., Tatemoto K., Coudray A.M., Rosselin G., Mutt V. [Bioactive "enteroglucagon" (oxyntomodulin): evidence for a C-terminal extension of the glucagon molecule] C. R. Seances Acad. Sci. III. 1981;293:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaudry J.L., Kaur K.D., Varin E.M., Baggio L.L., Cao X., Mulvihill E.E., Stern J.H., Campbell J.E., Scherer P.E., Drucker D.J. The brown adipose tissue glucagon receptor is functional but not essential for control of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol. Metab. 2019;22:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger J.P., Akiyama T.E., Meinke P.T. PPARs: therapeutic targets for metabolic disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;26:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bossart M., Wagner M., Elvert R., Evers A., Hübschle T., Kloeckener T., Lorenz K., Moessinger C., Eriksson O., Velikyan I., et al. Effects on weight loss and glycemic control with SAR441255, a potent unimolecular peptide GLP-1/GIP/GCG receptor triagonist. Cell Metab. 2022;34:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.12.005. e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt S.J., Müller T.D., DiMarchi R.D., Tschöp M.H., Stemmer K. Peptide-based multi-agonists: a new paradigm in metabolic pharmacology. J. Intern Med. 2018;284:581–602. doi: 10.1111/joim.12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bromer W.W., Sinn L.G., Staub A., Behrens O.K. The amino acid sequence of glucagon. Diabetes. 1957;6:234–238. doi: 10.2337/diab.6.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buenaventura T., Bitsi S., Laughlin W.E., Burgoyne T., Lyu Z., Oqua A.I., Norman H., McGlone E.R., Klymchenko A.S., Corrêa I.R., Jr., et al. Agonist-induced membrane nanodomain clustering drives GLP-1 receptor responses in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS Biol. 2019;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cajulao J.M.B., Hernandez E., von Zastrow M.E., Sanchez E.L. Glucagon receptor-mediated regulation of gluconeogenic gene transcription is endocytosis-dependent in primary hepatocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2022;33:ar90. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E21-09-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calbet J.A.L., MacLean D.A. Plasma glucagon and insulin responses depend on the rate of appearance of amino acids after ingestion of different protein solutions in humans. J. Nutr. 2002;132:2174–2182. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calebiro D., Nikolaev V.O., Gagliani M.C., de Filippis T., Dees C., Tacchetti C., Persani L., Lohse M.J. Persistent cAMP-signals triggered by internalized G-protein-coupled receptors. PLoS Biol. 2009;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calebiro D., Sungkaworn T. Single-molecule imaging of GPCR interactions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;39:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capozzi M.E., Wait J.B., Koech J., Gordon A.N., Coch R.W., Svendsen B., Finan B., D'Alessio D.A., Campbell J.E. Glucagon lowers glycemia when β-cells are active. JCI Insight. 2019:5. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.129954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cebecauer M., Amaro M., Jurkiewicz P., Sarmento M.J., Šachl R., Cwiklik L., Hof M. Membrane lipid nanodomains. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:11259–11297. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cegla J., Jones B.J., Gardiner J.V., Hodson D.J., Marjot T., McGlone E.R., Tan T.M., Bloom S.R. RAMP2 influences glucagon receptor pharmacology via trafficking and signaling. Endocrinology. 2017;158:2680–2693. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cegla J., Troke R.C., Jones B., Tharakan G., Kenkre J., McCullough K.A., Lim C.T., Parvizi N., Hussein M., Chambers E.S., et al. Coinfusion of low-dose GLP-1 and glucagon in man results in a reduction in food intake. Diabetes. 2014;63:3711–3720. doi: 10.2337/db14-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chabenne J.R., DiMarchi M.A., Gelfanov V.M., DiMarchi R.D. Optimization of the native glucagon sequence for medicinal purposes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2010;4:1322–1331. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakravarthy M., Parsons S., Lassman M.E., Butterfield K., Lee A.Y.H., Chen Y., Previs S., Spond J., Yang S., Bock C., et al. Effects of 13-hour hyperglucagonemia on energy expenditure and hepatic glucose production in humans. Diabetes. 2016;66:36–44. doi: 10.2337/db16-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng C., Jabri S., Taoka B.M., Sinz C.J. Small molecule glucagon receptor antagonists: an updated patent review (2015-2019) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020;30:509–526. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2020.1769600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen M., Bagger J.I., Vilsbøll T., Knop F.K. The alpha-cell as target for type 2 diabetes therapy. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2011;8:369–381. doi: 10.1900/rds.2011.8.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]