Abstract

An ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) was developed for the simultaneous quantitation of doxorubicin (DOX) and sorafenib (SOR) in rat plasma. Chromatographic separation was performed using a reversed-phase column C18 (1.7 μm, 1.0 × 100 mm Acquity UPLC BEH™). The gradient mobile phase system consisted of water containing 0.1% acetic acid (mobile phase A) and methanol (mobile phase B) with a flow rate of 0.40 mL/min over 8 min. Erlotinib (ERL) was used as an internal standard (IS). The quantitation of conversion of [M + H]+, which was the protonated precursor ion, to the corresponding product ions was performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) with a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of 544 > 397.005 for DOX, 465.05 > 252.03 for SOR, and 394 > 278 for the IS. Different parameters were used to validate the method including accuracy, precision, linearity, and stability. The developed UPLC–MS/MS method was linear over the concentration ranges of 9–2000 ng/mL and 7–2000 ng/mL with LLOQ of 9 and 7 ng/mL for DOX and SOR, respectively. The intra-day and inter-day accuracy, expressed as % relative standard deviation (RSD%), was below 10% for both DOX and SOR in all QC samples that have drug concentrations above the LLOQ. The intra-day and inter-day precision, expressed as percent relative error (Er %), was within the limit of 15.0% for all concentrations above LLOQ. Four groups of Wistar rats (250–280 g) were used to conduct the pharmacokinetic study. Group I received a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of DOX (5 mg/kg); Group II received a single oral dose of SOR (40 mg/kg), Group III received a combination of both drugs; and Group IV received sterile water for injection IP and 0.9% w/v sodium chloride solution orally to serve as a control. Non-compartmental analysis was used to calculate the different pharmacokinetic parameters. Data revealed that coadministration of DOX and SOR altered some of the pharmacokinetic parameters of both agents and resulted in an increase in the Cmax and AUC and reduction in the apparent clearance (CL/F). In conclusion, our newly developed method is sensitive, specific, and can reliably be used to simultaneously determine DOX and SOR concentrations in rat plasma. Moreover, the results of the pharmacokinetic study suggest that coadministration of DOX and SOR might cause an increase in exposure of both drugs.

Keywords: Doxorubicin, Sorafenib, Co-administration, UPLC-MS/MS, Pharmacokinetics

1. Introduction

Chemotherapeutic agents use in treating cancer is usually associated with some serious side effects, multi-drug resistance, and low bioavailability (Haider et al., 2022). One of the proposed approaches to overcome the previously mentioned drawbacks is the use of more than one agent in the treatment of cancer, this approach is called polychemotherapy or combination therapy. Doxorubicin (DOX), an anthracycline antibiotic, is mainly used in the treatment of solid tumors and is considered one of the most widely used antineoplastic agents (Injac and Strukelj 2008). DOX acts by inhibiting macromolecular biosynthesis through the intercalation of DNA and topoisomerase II inhibition (Naito et al., 2000). Patients with breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, testicular cancer, and lymphoma are usually prescribed DOX as the first-line chemotherapy (Hande 1998). Despite the broad-spectrum antitumor activity, many serious adverse effects are associated with DOX use such as nephrotoxicity, bone marrow depression, symptomatic effect and most importantly cardiotoxicity (Volkova and Russell 2011). These serious side effects have limited the use of conventional DOX in the management of cancer (Momparler et al., 1976, Gudkov et al., 1993, Slingerland et al., 2012, Kanwal et al., 2018). It has been also found that some cases of breast malignancies have acquired DOX resistance resulting in poor patient prognosis and survival rates (Christowitz et al., 2019).

Another option for cancer therapy is the hydrophobic sorafenib (SOR) which is an innovative bi-aryl urea (Shiota et al., 2010). SOR is also one of the most potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) it acts by inhibiting v-raf, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor (Wilhelm et al., 2004, Adnane et al., 2006). SOR is administered orally and is a valid treatment for advanced breast carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and thyroid cancer (Pitoia and Jerkovich, 2016, Zafrakas et al., 2016). It is also believed to inhibit tumor growth and progression, metastasis, angiogenesis, and anti-apoptosis down-regulation mechanisms (Abou-Alfa et al., 2010, Fishman et al., 2015, Gao et al., 2015).

Overcoming drug resistance and successful drug delivery continues to be the primary clinical challenges in treating breast cancer (Ozcelikkale et al., 2017). Previous reports indicated that DOX and SOR combination can enhance the effect of SOR, however, this combination was associated with higher toxicities (Abou-Alfa et al., 2019). Since the coadministration of two drugs can alter the pharmacokinetics of one or both drugs, thus hold responsibility of the high toxicities, a reliable analytical tool for the simultaneous detection of DOX and SOR is needed.

The development and validation of a simple yet sensitive assay method for the simultaneous detection of DOX and SOR was the main goal of the current study. In this article, we discussed how to simultaneously measure DOX and SOR in rat plasma using a quick ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC MS/MS) approach. The developed assay method was also used in a pharmacokinetic study for DOX and SOR conducted in rats.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

SOR tosylate (purity ˃ 99%) was purchased from Haoyuan Chemexpress Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, PR China), DOX hydrochloride (purity ˃ 99%), and erlotinib (ERL; purity 99%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC grade methanol and acetic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Milli-Q® A10 Advantage water purification system equipped with 0.22 μm filters (Millipore, Molsheim, France) was used to produce ultrapure water. Several batches of rat plasma were provided by the Women Student-Medical Studies and Sciences Sections, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. These samples were used to generate spiked standards and quality control samples.

2.2. Instrumentation and UPLC-MS/MS conditions

UPLC-MS/MS ultraperformance LC system (Waters, Singapore) was used for sample analysis, electrospray ionization (Zspray™ ESI-APCI-ESCI) which is linked to the system and in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode and equipped with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometric detector (Xevo TQ-S, Waters, Singapore). A binary solvent manager and sample manager (Acquity™) was also connected to the instrument. Masslynx™ Version 4.1 software with Targetlynx™ application manager (Micromass, Manchester, UK) was used to operate and control the system and for data processing. All samples were filtered before the injection into the LC-MS/MS system using disposable nylon CHROMAFIL® Xtra PA, 25 mm syringe filters with a pore size of 0.2 μm (MACHEREY NAGEL GmbH & Co. KG Duren, Germany).

The MS/MS system was operated using MRM mode for quantitation using electrospray ionization in positive ionization mode. MRM was used to monitor the transitional change from [M + H]+ to the product ions of m/z 544 > 397.005 for DOX, 465.05 > 252.03 for SOR and 394 > 278 for the IS. The MS source temperature was 150 °C, desolvation temperature was maintained at 350 °C, capillary voltage 3.8 kV, collision energy 2 eV, cone voltage 50 V, and the dwell time is 0.05 S. The cone gas flow rate adjusted at 20 L/h, the desolvation gas at 600 L/h for, and collision gas at 0.10 mL/min. LM resolution of 2.5 and HM resolution of 15 were used to operate MS analyzers. A flow rate of 0.40 mL/min was used for the UPLC analysis and a reversed-phase column was used (C18) (1.7 μm, 1.0 × 100 mm Acquity UPLC BEH™, Waters, Ireland). A gradient elution was performed at time zero began with a mobile phase consisting of 80% water with 0.1% acetic acid and 20% methanol, methanol was then increased to 90% over 1 min then back to 20% over 8 min. The injection volume was 10 μL using partially filled loop and needle overfill mode. The temperature was maintained at 45 °C in the column and at 4 °C in the autosampler throughout the entire run time.

2.3. Preparation of stock solutions and standard solutions

A mixed stock solution of DOX and SOR, and a separate stock solution of IS was prepared in methanol (MeOH) to reach a concentration of 1 mg/mL (final concentration). DOX and SOR stock solutions were furthermore diluted in MeOH to prepare a series of standard solutions concentrations of 9–2000 and 7–2000 ng/mL for DOX and SOR respectively. To produce working standards and for the construction of calibration curves a separate diluted standard solution of the IS (1 µg/mL) was also prepared.

2.3.1. Preparation of the calibration samples and quality control samples

Twenty-five μL of blank plasma was spiked with the corresponding DOX and SOR standard solution followed by the addition of 20 μL of IS to each sample to prepare the calibration samples. Then all the samples were further diluted with MeOH to obtain a final volume of 1 mL. Four different concentrations of DOX and SOR including 20 ng/mL (very low), 70 ng/mL (low), 600 ng/mL (medium), and 800 ng/mL (high) were used to prepare quality control samples (QC). The preparation of blank samples was done by adding MeOH to 25 μL of plasma samples to prepare 1 mL. All stock and working standards were kept at − 80 °C until the time of analysis.

2.3.2. Samples preparation

Frozen plasma samples (-80 °C) were allowed to thaw at room temperature, then 25 μL of each treated plasma sample was withdrawn and 20 μL of IS and then methanol was added to each sample to complete the volume to 1 mL. Samples were then vortexed in a micro centrifuge tube (1.5 mL) for one minute and the precipitated proteins were separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. Thereafter, collection of the supernatant was done. The collected supernatant was then filtered by 0.2 μm disc before injection into the system.

2.4. Method validation

According to the requirement of the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) for the bioanalytical method validation, several tests should be performed to validate the method such as linearity, extraction recovery, selectivity, accuracy, and precision.

2.4.1. Selectivity and specificity

To investigate the selectivity of the method, to rule out any plasma interferences from plasma matrices, four different batches of blank plasma samples were obtained, analyzed, and compared to chromatograms spiked with very low concentration of DOX and SOR at lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) which were 9 and 7 ng/mL respectively. The IS was added to all prepared samples. The response signals of DOX, SOR, and IS at their retention times were used to confirm the absence of any interference in bland and spiked plasma samples.

2.4.2. Linearity and standard curve

A set of plasma samples with different concentrations (9–2000 and 7–2000 ng/mL) for DOX and SOR respectively were used to evaluate linearity. Peak area ratios of DOX and SOR to IS were utilized for the construction of the matrix-based calibration curve and to also obtain DOX and SOR regression equations.

2.4.3. Evaluation of lower limit of detection and quantification

Lower limit of detection (LLOD) which represent the lowest detectable drug concentration and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) which represents the lowest quantifiable drug concentration with an appropriate accuracy and precision (i.e., with deviations lower than ± 20%). LLOD and LLOQ were evaluated practically based on analytical responses. LLOD is when the response is at least three times the signal obtained from a blank sample. LLOQ is when the response is ten times when compared to the blank signal. The same retention time of both analytes (DOX and SOR) should be used for all measurements.

2.4.4. Precision and accuracy

Evaluation of both inter-day and intra-day accuracy and precision was performed by analyzing LLOQ for each drug 9 ng/mL for DOX and 7 ng/mL for SOR and the prespecified quality control (QC) samples (20, 70, 600, and 800). For intra-day assay the QC samples were analyzed three times on the same day and for inter-day assay the test was done on three successive days for each of DOX, SOR and IS. The percentage of deviation from the corresponding nominal value percent relative error (Er %) was used to assess accuracy while the precision was assessed using percentage relative standard deviation (RSD %) of the results.

2.4.5. Matrix effect

The same QC samples in the concentration of 20, 70, 600, and 800 ng/mL were used to assess the matrix effect. Calculations for concentration of each drug were based on peak responses from post extracted samples and those responses from standard solutions having the same nominal concentration.

2.4.6. Extraction recovery

The four QC samples (20, 70, 600, and 800 ng/mL) were used to evaluate the extraction recoveries both drugs from plasma samples, the experiment was done in triplicates. Also, the IS recovery was evaluated using the same concentration that was used for the actual analysis. The evaluation of extraction recovery was done by comparing the peak response obtained from the spiked QC samples in blank matrix to the peak response resulted from spiked samples after extraction.

2.4.7. Stability studies

Percentage recoveries were utilized to assess the stability of DOX and SOR under different storage and processing conditions such as short-term stability (bench top stability), which was performed by keeping the tested samples at 25 °C (room temperature) for 6 h. Moreover, the prepared samples were placed in the auto-injector (4 °C) for 48 h before injection to evaluate the auto-sampler stability. Long-term stability was evaluated by examining samples that were frozen before analysis (-80 °C, 60 days) and freeze–thaw stability was also evaluated by performing three cycles freezing at −80 °C, and thawing at 25 °C. QC samples at low (20 ng/mL) and high (800 ng/mL) concentration levels were analyzed for each analyte using six replicates.

2.4.8. Carryover effect

High analytes concentrations were used to spike plasma samples, which were then analyzed. Three blank samples were injected immediately afterwards. The retention time of each analyte (DOX, SOR and IS) was used to record the obtained peak areas.

2.4.9. Dilution integrity

Dilution is usually needed when using high drug concentrations in plasma samples before the actual analysis. High concentration of both drugs (700 ng/mL) was used to spike plasma samples and the extraction recovery was calculated and used to evaluate the integrity of dilution, several dilution ratios (1:2), (1:3), (1:5) and (1:6) were used to analyze the samples.

2.5. Application to pharmacokinetic studies in rats

2.5.1. Design of the study

Healthy male Wistar rats at the weight of 250–280 g were provided by the animal house, College of Pharmacy, Women Student-Medical studies and Sciences Sections, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Standard laboratory conditions and well-ventilated room were used to keep the animals for one week before starting the experiment for the animals to adapt. The research laboratory conditions were temperature in the range of 24–27 °C, a relative humidity of 40–60%, and 12 h day/night cycle, animals had free access to food and water 12 h before drugs administration. Four groups of rats, 5 rats (n = 5) in each group were randomly selected and grouped as follows: Group I administered a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of DOX 5 mg/kg. Group II administered a single oral dose of SOR in a concentration of 40 mg/kg and was administered via oral gavage. Group III administered a single IP injection of DOX (5 mg/kg) and a single oral dose of SOR (40 mg/kg) through oral gavage. Group IV, which served as the control group, was injected with water for injection (IP) and administered 0.9% w/v sodium chloride solution (normal saline) orally.

Free access to water and food was available for all rats in the experiment. Then on the night of the study water was allowed but food was withheld overnight. Tail vein of each rat was used to collect 300 µL. A series of heparinized tubes were used to collect the blood samples. Sample withdrawal was performed at (0 time) before drug administration. Then blood samples were withdrawn at different time points: 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48 and 72 h after administration. The obtained samples were instantly centrifuged at 4,500 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min to obtain plasma, which were then stored at − 20 °C until analysis. Twenty μL of IS in a concentration of 1 µg/mL was added to 25 μL of each plasma sample, and methanol was then used to complete the volume to 1 mL. Sample preparation that was used in section 2.4 was followed to process the plasma samples. According to the Research Ethics Committee at King Saud University, all experiments were conducted in conformity with the ethical standards for animal experimental studies (Reference no. KSU-SE-19–13).

2.5.2. Pharmacokinetic and statistical analysis

For pharmacokinetic studies, an add-in program for excel (PK solver) was used to calculate the pharmacokinetics parameters of DOX and SOR from the plasma concentrations-time data. The major pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using non-compartmental analysis. Specifically, the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time at which it occurred (Tmax) were determined by visual examination of the data. The elimination rate constant (λz) was estimated by linear regression of the plasma concentrations in the log-linear terminal phase and the corresponding half-life (t1/2) was calculated by dividing 0.693 by λz. The AUC0-∞ was calculated using the linear trapezoidal method from time 0 h post dose to the time of the last measured concentration, plus the quotient of the last measured concentration divided by λz. The apparent clearance (CL/F) was calculated by dividing dose by AUC0-∞.

All data are reported as mean ± SD. Differences between the means were compared by Student's unpaired t-test. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chromatographic conditions optimization

Different chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions were tried to optimize specificity and sensitivity. All conditions that directly affect these parameters and conditions were studied individually. First, chromatographic conditions were optimized by using and evaluating different analytical columns such as C8 and C18 Acquity UPLC BEH™ (1 mm × 100 mm, i.d., 1.7 μm particle size). Mobile phase compositions including mixtures of organic solvents in different ratios were evaluated such as acetonitrile (30–90%), formic acid (0.05–0.2 %) along with water. Methanol (10–90%), water, and acetic acid (0.05–0.2 %) were also evaluated.

Best chromatographic results (sharp, symmetric and high well-defined peaks with no interference) were achieved by using C18 Acquity UPLC BEH™ (100 × 1.0 mm, i.d., 1.7 μm particle size) as a stationary phase and gradient elution using a mobile phase consisting of 20% methanol and 80% water with 0.1 % acetic acid at time zero, methanol was then increased to 90% over 1 min then back to 20% over 8 min. Run time was 10 min for DOX, SOR, and IS with retention times of 1.75, 5.24, and 3.07 min, respectively.

For the optimization of mass spectrometric conditions, ESI at both positive and negative ionization mode were tested and found that ESI at the positive mode provided sufficient ionization for both analytes and IS. The protonated precursor ion [M + H]+ was detected at the prespecified mass to charge ratio m/z of 544 for DOX, 465.05 for SOR, and 394 for the IS. Fig. 1 of the product ion spectra shows that major fragmentation occurred at m/z 397.005 (DOX), m/z 252.03 (SOR) and m/z 278 (IS). Quantification of analytes and IS was performed using the previously mentioned MRM products. The highest response and the optimal intensity for both analytes and IS were obtained by carefully optimizing MS parameters such as ESI source temperature, cone voltage, capillary voltage, flow rate of desolvation gas, and desolvation temperature.

Fig. 1.

Generated product ion spectra of (a) DOX, (b) SOR, (c) IS.

3.2. Method validation

3.2.1. Selectivity and specificity

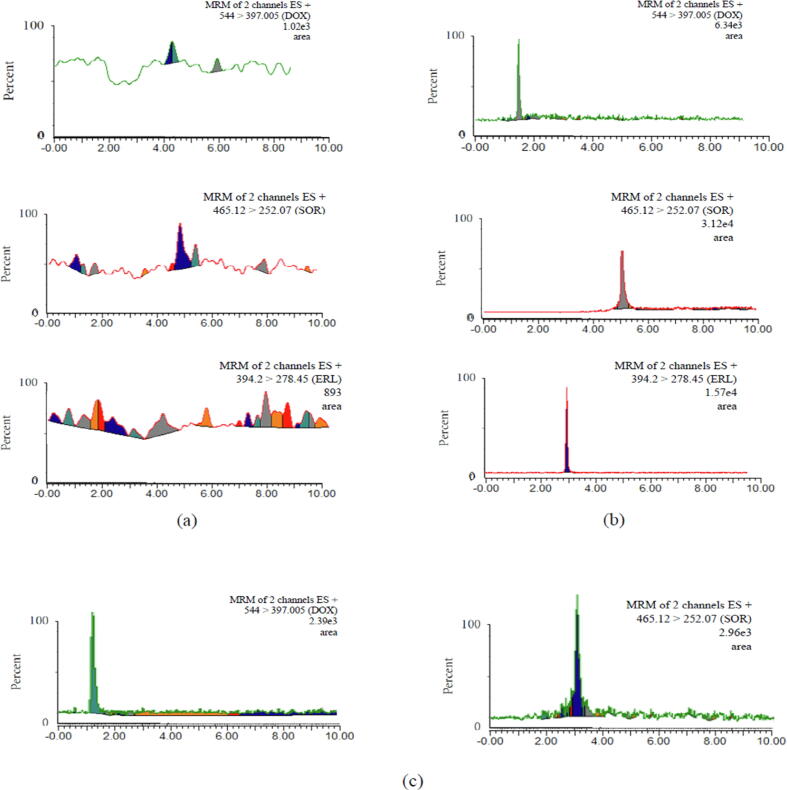

Under the established chromatographic method, it has been found that endogenous elements had no interfering peaks recorded at the retention times of DOX, SOR or IS. The specificity was determined by comparing blank plasma samples with samples spiked with each of the analytes at the LLOQ (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

MRM of (a) blank sample of plasma; (b) spiked plasma sample with LLOQ of DOX and SOR with IS; (c) rat plasma samples 4 h after administration of DOX (5 mg/kg) and SOR (40 mg/kg).

3.2.2. Linearity and standard curve

Using this method resulted in an excellent linearity (R2 ≥ 0.999) between the spiked concentration and the analyte peak area/IS ratio within the range of 9–2000 and 7–2000 ng/mL for DOX and SOR respectively. After plotting the peak area ratio of DOX and SOR to IS, least-squares regression was utilized to determine the line of best fit. A typical regression line in plasma was obtained for DOX (y = 0.0138x + 0.2363) and for SOR (y = 0.0092x − 0.0034), where y is the peak area/IS ratio of each analyte and × is the spiked concentrations. The plotted calibration curves resulted in high correlation coefficient for DOX and SOR R2 = 0.9997 and R2 = 0.9997, respectively.

3.2.3. Evaluation of lower limit of detection and quantification

LLOD and LLOQ in plasma samples for DOX were 3, and 9 ng/mL, and for SOR were 5 and 7 ng/mL, respectively on the basis of the criteria mentioned in the experimental section.

3.2.4. Precision and accuracy

Intra-day method precision was calculated as RSD% and fell within the range of (1.3 to 5.1%) and (0.3 to 4%) for DOX and SOR, respectively. RSD% for inter-day levels fell in the range of (1.4 to 6.5%) and (6.1 to 9.8%) for DOX and SOR, respectively. The accuracy was expressed as percent relative error (Er %) and fell in the range of (-8.8 to −2.7%) and (-7.0 to 13.9%) for DOX and SOR, respectively for intra-day. The accuracy for inter-day was in the range of (-4.6 to 2.9%) and (-8.3 to 9.1%) for DOX and SOR, respectively. All obtained results show that the established method is precise and accurate with deviations ±<15%, which is the acceptance limit for precision and accuracy. Table 1 summarizes the results for intra-day and inter-day precision and accuracy that were obtained from the analysis of LLOQ of each drug and QC samples.

Table 1.

Intra-day and inter-day accuracy and precision evaluation for the determination of DOX and SOR in rat plasma by the developed UPLC-MS/MS method.

| Analytes | Concentration ng/mL | Intra-day |

Inter-day |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean recovery (%) ± SD | RSD (%) | Er (%) | Mean recovery (%) ± SD | RSD (%) | Er (%) | ||

| DOX | 800 | 93.35 ± 2.9 | 3.1 | −6.5 | 96.68 ± 2.5 | 2.6 | −3.1 |

| 600 | 92.98 ± 1.2 | 1.3 | −6.8 | 97.16 ± 4.7 | 4.8 | −2.6 | |

| 70 | 91.40 ± 4.1 | 4.4 | −8.8 | 95.63 ± 1.3 | 1.4 | −4.6 | |

| 20 | 94.61 ± 1.8 | 1.9 | −2.7 | 94.77 ± 2.1 | 2.2 | −2.5 | |

| 9 | 99.04 ± 4.9 | 5.1 | −2.8 | 94.17 ± 6.2 | 6.5 | 2.9 | |

| SOR | 800 | 95.08 ± 2.4 | 2.5 | −3.9 | 90.65 ± 5.5 | 6.1 | −8.3 |

| 600 | 91.81 ± 0.3 | 0.3 | −6.6 | 90.33 ± 5.7 | 6.3 | −8.1 | |

| 70 | 95.92 ± 2.5 | 2.6 | 13.9 | 97.95 ± 9.6 | 9.8 | 9.1 | |

| 20 | 92.11 ± 1.5 | 1.6 | −7.03 | 87.30 ± 6.5 | 7.5 | −2.2 | |

| 7 | 100.1 ± 3.9 | 4 | −2.2 | 99.04 ± 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.7 | |

3.2.5. Matrix effect

Matrix effect was assessed by using QC samples (20, 70, 600 and 800) as shown in Table 2. Errors of less than −1.4% were obtained for DOX and less than −0.6% for SOR. This proves that the method has the capability to determine very low concentrations of the analytes and with a very low possibility for matrix-induced ion suppression or ion enhancement (Table 2).

Table 2.

Extraction recovery and matrix effect evaluation of DOX and SOR in rat plasma.

| Analytes | Concentration ng/mL | Extraction recovery |

Matrix effect |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean recovery (%) ± SD | RSD (%) | Er (%) | Mean recovery (%) ± SD | RSD (%) | Er (%) | ||

| DOX | 800 | 108.89 ± 3.4 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 100.79 ± 4 | 3.9 | 7.4 |

| 600 | 99.11 ± 14.5 | 14.6 | −2.7 | 101.96 ± 7.2 | 7.1 | 5.7 | |

| 70 | 111.86 ± 3.5 | 3.2 | −11.5 | 111.67 ± 3.9 | 3.4 | −0.4 | |

| 20 | 120.50 ± 4.1 | 3.4 | −8.06 | 123.67 ± 2.4 | 1.9 | −1.4 | |

| SOR | 800 | 108.81 ± 3.8 | 3.5 | 8.9 | 113.03 ± 6.5 | 5.8 | 10.3 |

| 600 | 92.12 ± 6.6 | 7.2 | −7.7 | 98.91 ± 5.5 | 5.6 | −0.6 | |

| 70 | 103.54 ± 8.1 | 7.8 | 4.1 | 121.33 ± 8.9 | 7.3 | 1.9 | |

| 20 | 104.8 ± 6.2 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 106.94 ± 10.2 | 9.5 | 0.2 | |

3.2.6. Extraction recovery

The extraction recovery was assessed using the QC samples of DOX and SOR. Extraction recovery values of 99.11% and 92.12% were obtained for DOX and SOR, respectively, as shown in Table 2. The efficiency of the applied method for the extraction of DOX and SOR from plasma samples is indicated by the high values of the extraction recoveries.

3.2.7. Stability studies

All results of the stability tests for DOX and SOR in rat plasma under different storage conditions are summarized in Table 3. According to the results, both analytes were stable at the autosampler for up to 48 h and at − 80 °C for up to 60 days, and the Er% and RSD% values were within the acceptable range of ± 15%.

Table 3.

Stability evaluation for DOX and SOR in rat plasma.

| Analytes | Condition | Concentration ng/mL | Mean recovery (%) ± SD | RSD (%) | Er (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOX | Autosampler stability (4c 48 h) | 800 | 98.95 ± 4.8 | 4.8 | −0.9 |

| 20 | 102.09 ± 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.7 | ||

| Autosampler stability (4 °C 6 h) | 800 | 105.42 ± 2.9 | 2.8 | 5.5 | |

| 20 | 95.94 ± 3.1 | 3.2 | −1.4 | ||

| long term stability (-80 °C 30 day) | 800 | 94.24 ± 4.7 | 5.0 | −5.6 | |

| 20 | 98.15 ± 3.1 | 3.2 | 0.7 | ||

| freeze thaw stability (-80 °C 60 days) | 800 | 95.42 ± 0.7 | 0.7 | −5.6 | |

| 20 | 96.54 ± 2.6 | 2.7 | 0.7 | ||

| SOR | Autosampler stability (4c 48 h) | 800 | 93.69 ± 1.8 | 1.9 | −5.3 |

| 20 | 101.43 ± 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | ||

| Autosampler stability (4 °C 6 h) | 800 | 93.63 ± 0.2 | 0.3 | −5.4 | |

| 20 | 96.50 ± 4.2 | 4.3 | −3.4 | ||

| long term stability (-80 °C 30 day) | 800 | 92.13 ± 0.9 | 1.0 | −6.9 | |

| 20 | 97.84 ± 5.8 | 6.0 | −2.1 | ||

| freeze thaw stability (-80 °C 60 days) | 800 | 92.86 ± 0.8 | 0.9 | −5.8 | |

| 20 | 100.14 ± 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.1 |

3.2.8. Carryover effect

Following the injection of highly concentrated plasma samples, blank samples were injected directly afterwards and showed no peaks at the retention time of DOX and SOR and IS. The developed UPLC-MS/MS method successfully showed no carryover effect when analyzing DOX and SOR.

3.2.9. Dilution integrity

From the data showed in Table 4, the dilution of plasma samples did not affect the recovery % results since the RSD% as well as Er% values were consistently<15% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Dilution integrity evaluation for DOX and SOR in rat plasma.

| Analytes | Concentration ng/mL | Dilution | Extraction recovery |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean recovery (%) ± SD | RSD (%) | Er (%) | |||

| DOX | 700 | 1:2 | 83.88 ± 0.2 | 0.3 | −14.92 |

| 1:3 | 83.79 ± 0.3 | 0.3 | −13.43 | ||

| 1:5 | 81.81 ± 4.7 | 6 | −12.18 | ||

| 1:6 | 93.29 ± 6.5 | 7.1 | −11.35 | ||

| SOR | 700 | 1:2 | 120.75 ± 0.7 | 0.6 | 14.05 |

| 1:3 | 98.66 ± 0.4 | 0.5 | −1.68 | ||

| 1:5 | 116.30 ± 7.1 | 6.1 | 11.32 | ||

| 1:6 | 117.13 ± 8.3 | 7.1 | 11.24 | ||

3.3. Application to pharmacokinetic studies in rats

In this work, we evaluated the possibility of applying the developed analytical method to characterize the pharmacokinetics of DOX and SOR by determining their concentrations in rat plasma. The MRM chromatograms of DOX and SOR in plasma samples 4 h post-dose are shown in Fig. 2C. DOX and SOR plasma concentration–time profiles are shown in Fig. 3. Following a single IP administration of DOX (5 mg/kg), the drug was rapidly absorbed and reached the Cmax (196.1 ng/mL) within 1 h (Tmax). The concentrations then declined to reach 11 ng/mL at 72 h, with a calculated elimination t1/2 of nearly 51 h. However, coadministration of DOX with a single oral dose of SOR (40 mg/kg) resulted in a significantly higher plasma concentrations of DOX (Fig. 3). Specifically, the Cmax reached 846 ng/mL, which was 4.32-fold higher than the one obtained in DOX alone (p < 0.05). The calculated AUC0-72h was approximately 2-fold higher than the AUC obtained with DOX alone (1857 vs 3617 ng.h/mL) (p < 0.05). Moreover, the estimated AUC0-∞ was approximately 2.3-fold higher than the AUC obtained with DOX alone (2781.9 vs 6271.1 ng.h/mL) (p < 0.05). Furthermore, there was a significant reduction in the CL/F of DOX upon co-administration with SOR (p < 0.05). This could be attributed to the inhibitory effects of SOR on the efflux membrane transporters (MRP-2 and P-glycoprotein) (Swift et al., 2013, Vasilyeva et al., 2015, Karbownik et al., 2021), which significantly contribute to DOX clearance (Vlaming et al., 2006, Yamaguchi et al., 2006). In fact, the major route of drug elimination in humans is via biliary excretion, for example DOX after 5 min of a single intravenous appears in bile (Riggs et al., 1977). Moreover, approximately 40% of injected drug is excreted in bile when compared to excretion in urine which accounts for 14% only (Riggs et al., 1977). Similar relation between total biliary excretion and urinary excretion have been observed in animals, including rats (Yesair et al., 1972, Tavoloni and Guarino, 1980). Furthermore, Binkhathlan et al. (Binkhathlan et al., 2012) have shown that co-administration of DOX with Cyclosporine A, which is a known P-gp and MRP-2 inhibitor, resulted in a significant reduction in CL of DOX that caused a significant increase in the AUC of the drug in plasma. Therefore, it was not surprising to observe such PK drug-drug interaction between DOX and SOR. In fact, it is in line with the results obtained from a Phase I clinical trial, where DOX showed an increased AUC (21%) and Cmax (33%) when administered with SOR (Richly et al., 2009).

Fig. 3.

Concentration-time profile in rat plasma after the administration of DOX (5 mg/kg) or SOR and (40 mg/kg) and co-administration of both drugs (n = 5).

Following a single oral administration of SOR (40 mg/kg), the drug was absorbed and reached the Cmax (20.4 ng/mL) within 4 h (Tmax). The concentrations then declined to reach ∼ 5 ng/mL at 48 h (concentrations at 72 h were below the LLOQ), with a calculated elimination t1/2 of nearly 42 h. Upon co-administration with DOX, SOR showed a significantly higher Cmax than the one obtained with SOR alone, which was also attained faster (Tmax was 2 h). Nonetheless, the differences among the mean values of the other PK parameters were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4) (Table 5). Overall, based on the data presented here, although both drugs are substrates to P-gp and MRP-2, it seems that SOR have a more significant impact on the PK of DOX rather than the other way around.

Fig. 4.

Main pharmacokinetic parameters of (a) DOX and (b) SOR after single or co-administration. Asterisks (*) were used to indicate statistical significance, where * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Table 5.

Main pharmacokinetic parameters (mean ± SD) following IP administration of DOX, oral administration of SOR and co-administration to rats (n = 5).

| GROUP I DOX (5 mg/kg) | GROUP III DOX Mix | GROUP II SOR (40 mg/kg) | GROUP III SOR Mix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 196.1 ± 166.2 | 846.9 ± 60.4 | 20.4 ± 3.6 | 29.6 ± 3.6 |

| Tmax (h)* | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| AUC0-t (ng.h/mL) | 1856.6 ± 459.8 | 3617.7 ± 322.9 | 547.1 ± 125.7 | 398.6 ± 118.7 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng.h/mL) | 2781.9 ± 366.8 | 6271.1 ± 1975.5 | 591.6 ± 141.3 | 557.9 ± 195.7 |

| t½ (h) | 51.1 ± 18.9 | 68.2 ± 37.6 | 18.3 ± 3.1 | 42.8 ± 24.2 |

| CL/F (L/h/kg) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 70.7 ± 16.4 | 77.7 ± 23.7 |

*Tmax (h) is presented as a median.

4. Conclusion

In summary, a selective, simple, and fast UPLC-MS/MS assay method for DOX and SOR was developed and validated. The method was capable of simultaneously quantifying DOX and SOR in rat plasma and was proved to be reliably used in pharmacokinetic studies. The co-administration of DOX and SOR showed significant alterations in the DOX pharmacokinetic parameters including an increase in the drug exposure, which could possibly increase the side effects of the drug. These findings should be further investigated to evaluate the safety of this combination and to design a proper dosage regimen.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the Research Supporting Project number (RSP2023R215), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for funding this research.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abou-Alfa G.K., Johnson P., Knox J.J., et al. Doxorubicin plus sorafenib vs doxorubicin alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:2154–2160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Alfa G.K., Shi Q., Knox J.J., et al. Assessment of treatment with sorafenib plus doxorubicin vs sorafenib alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Phase 3 CALGB 80802 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1582–1588. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adnane L., Trail P.A., Taylor I., et al. Sorafenib (BAY 43–9006, Nexavar), a dual-action inhibitor that targets RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in tumor cells and tyrosine kinases VEGFR/PDGFR in tumor vasculature. MethodsEnzymol. 2006;407:597–612. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(05)07047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkhathlan Z., Shayeganpour A., Brocks D.R., et al. Encapsulation of P-glycoprotein inhibitors by polymeric micelles can reduce their pharmacokinetic interactions with doxorubicin. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012;81:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christowitz C., Davis T., Isaacs A., et al. Mechanisms of doxorubicin-induced drug resistance and drug resistant tumour growth in a murine breast tumour model. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:757. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5939-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman M.N., Tomshine J., Fulp W.J., et al. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety experience reported for sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in the post-approval setting. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.J., Shi Z.Y., Xia J.F., et al. Sorafenib-based combined molecule targeting in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12059–12070. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov A.V., Zelnick C.R., Kazarov A.R., et al. Isolation of genetic suppressor elements, inducing resistance to topoisomerase II-interactive cytotoxic drugs, from human topoisomerase II cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:3231–3235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider M., Elsherbeny A., Pittalà V., et al. Nanomedicine strategies for management of drug resistance in lung cancer. Journal. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23031853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hande K.R. Clinical applications of anticancer drugs targeted to topoisomerase II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Struct. Expression. 1998;1400:173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(98)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Injac R., Strukelj B. Recent advances in protection against doxorubicin-induced toxicity. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;7:497–516. doi: 10.1177/153303460800700611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal U., Irfan Bukhari N., Ovais M., et al. Advances in nano-delivery systems for doxorubicin: an updated insight. J. Drug Target. 2018;26:296–310. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2017.1380655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbownik A., Szkutnik-Fiedler D., Grabowski T., et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interaction study of sorafenib and morphine in rats. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler R.L., Karon M., Siegel S.E., et al. Effect of adriamycin on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in cell-free systems and intact cells. Cancer Res. 1976;36:2891–2895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito S., Koga H., Yokomizo A., et al. Molecular analysis of mechanisms regulating drug sensitivity and the development of new chemotherapy strategies for genitourinary carcinomas. World J. Surg. 2000;24:1183–1186. doi: 10.1007/s002680010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcelikkale A., Shin K., Noe-Kim V., et al. Differential response to doxorubicin in breast cancer subtypes simulated by a microfluidic tumor model. J. Control. Release. 2017;266:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitoia F., Jerkovich F. Selective use of sorafenib in the treatment of thyroid cancer. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2016;10:1119–1131. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S82972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richly H., Schultheis B., Adamietz I.A., et al. Combination of sorafenib and doxorubicin in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results from a phase I extension trial. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45:579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs C.E., Jr., Benjamin R.S., Serpick A.A., et al. Bilary disposition of adriamycin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1977;22:234–241. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977222234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota M., Eto M., Yokomizo A., et al. Sensitivity of doxorubicin-resistant cells to sorafenib: possible role for inhibition of eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha phosphorylation. Int. J. Oncol. 2010;37:509–517. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland M., Guchelaar H.J., Gelderblom H. Liposomal drug formulations in cancer therapy: 15 years along the road. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift B., Nebot N., Lee J.K., et al. Sorafenib hepatobiliary disposition: mechanisms of hepatic uptake and disposition of generated metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013;41:1179–1186. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.048181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavoloni N., Guarino A.M. Biliary and urinary excretion of adriamycin in anesthetized rats. Pharmacology. 1980;20:256–267. doi: 10.1159/000137371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyeva A., Durmus S., Li L., et al. Hepatocellular shuttling and recirculation of sorafenib-glucuronide is dependent on Abcc2, Abcc3, and Oatp1a/1b. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2729–2736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-15-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaming M.L., Mohrmann K., Wagenaar E., et al. Carcinogen and anticancer drug transport by Mrp2 in vivo: studies using Mrp2 (Abcc2) knockout mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;318:319–327. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkova M., Russell R., 3rd Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: prevalence, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2011;7:214–220. doi: 10.2174/157340311799960645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S.M., Carter C., Tang L., et al. BAY 43–9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S., Zhao Y.L., Nadai M., et al. Involvement of the drug transporters p glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein Mrp2 in telithromycin transport. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:80–87. doi: 10.1128/aac.50.1.80-87.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesair D.W., Schwartzbach E., Shuck D., et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics of daunomycin and adriamycin in several animal species. Cancer Res. 1972;32:1177–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafrakas M., Papasozomenou P., Emmanouilides C. Sorafenib in breast cancer treatment: A systematic review and overview of clinical trials. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;7:331–336. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v7.i4.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]