Abstract

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has been extensively applied to current biomedical research. From such large-scale identification of proteins, several computational tools have been developed for determining protein–protein interactions (PPI) network and functional significance of the identified proteins and their complex. Analyses of PPI network and functional enrichment have been widely applied to various fields of biomedical research. Herein, we summarize commonly used tools for PPI network analysis and functional enrichment in kidney stone research and discuss their applications to kidney stone disease (KSD). Such computational approach has been used mainly to investigate PPI networks and functional significance of the proteins derived from urine of patients with kidney stone (stone formers), stone matrix, Randall’s plaque, renal papilla, renal tubular cells, mitochondria and immune cells. The data obtained from computational biotechnology leads to experimental validation and investigations that offer new knowledge on kidney stone formation processes. Moreover, the computational approach may also lead to defining new therapeutic targets and preventive strategies for better outcome in KSD management.

Keywords: Calcium oxalate, Computational approach, Crystal receptor, Mechanism, Prevention, Therapeutic target

Introduction

Proteins are the functioning biological macromolecules involved in almost all of biological processes and pathways. Usually, proteins work together as a complex and are regulated by others to govern dynamic cellular functions. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics is the powerful high-throughput technique for proteome profiling and analyzing alterations in protein expression to define cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenic processes in several diseases, e.g., cancers [1], neurodegenerative diseases [2], and kidney disorders [3]. Additionally, studying proteins and their interacting complex frequently leads to clearer understanding of their roles in a given biological system. Several experimental techniques have been applied for detection of protein interacting partners and their complex, such as immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry (IP-MS), tandem affinity purification followed by mass spectroscopy (TAP-MS), yeast two-hybrid system (Y2H) and protein-fragment complementation assay (PCA) [4].

Following large-scale identification of the proteins and their interacting complex as mentioned above, several computational tools have been developed for determining the protein–protein interactions (PPI) network and functional significance of the identified proteins and their complex. Analyses of PPI network and functional enrichment have been widely applied to various fields of biomedical research. Herein, we summarize commonly used tools for PPI network analysis and functional enrichment in kidney stone research and discuss their applications to kidney stone disease (KSD).

Commonly used tools for PPI network analysis and functional enrichment in kidney stone research

Computational tools for analyses of PPI and chemico-protein interactions

One of the well-known and widely used tools is a freely accessible, web-based Search Tool for Recurring Instances of Neighbouring Genes (STRING) (https://string-db.org/). This tool was firstly introduced in 2000 and has been regularly updated [5]. STRING constructs the PPI network based on both physical and functional associations of proteins retrieved from known associations and from prediction [5]. The main sources of data generated by STRING include (i) interactions data from experimental studies, (ii) computationally annotated complexes/pathways from previous knowledge in database, (iii) automated text mining from literatures, (iv) genomic context prediction, and (v) transferred evidence from other organisms [5]. The interactions score provided in STRING is calculated from all sources of the interactions, ranging from 0 to 1 (1 is the highest confident score) [5]. The PPI network delivered by STRING can be also visualized by using Cytoscape platform (https://cytoscape.org/) [6] and various packages in R software (https://www.r-project.org/). FunRich (http://www.funrich.org/) is another freely accessible, stand-alone tool widely used for construction of the PPI network [7]. The evidence of interactions in FunRich tool is based on selected databases, including BioGRID (https://thebiogrid.org/), IntAct (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/), Human Proteinpedia (http://humanproteinpedia.org/), Human Protein Reference Database (https://www.hprd.org/) and UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) [7]. The PPI network can be also constructed by using a commercial software package, QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool [8].

Another interesting and useful tool is Significance Analysis of INTeractome (SAINT) (https://saint-apms.sourceforge.net/Main.html). This tool is applicable for analyzing the data derived from AP-MS and TAP-MS [9]. SAINT provides the confidence scores based on MS data and probability-based model to improve the experimental-based PPI detectability [9,10]. This tool can be also applied for clarifying the true PPI after AP-MS and TAP-MS experiments [9,10]. In addition to PPI, proteins can be interacted with other molecules, including ions, chemical compounds and ligands. The available computational tool used for identifying chemico–protein interactions is STITCH (http://stitch.embl.de/) [11]. The main sources of interactions evidence in STITCH resemble those for STRING.

Computational tools for functional enrichment analysis

In addition to PPI network analysis, functional enrichment analysis is very helpful for clearer understanding of the biological meanings of a large protein dataset. Based on the benefits from two available knowledgebases, Gene Ontology (GO) (http://www.geneontology.org/) [12] and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) [13], several functional enrichment tools have been made available for predicting functions and involved pathways of the proteins of interest as well as their networks. GO knowledgebase is the most comprehensive resource providing functions of genes and their products [12]. There are three main categories of GO terms, including molecular function, biological process, and cellular component [12]. The molecular function is defined as molecular activity of the gene products, whereas biological process is the biological event associated with various molecular activities. Cellular component is the information for cellular locale in which gene products localize and perform their functions [12]. KEGG pathway encyclopedia provides the information containing manually drawn pathway maps according to networks of molecular interactions, reaction/relation and computationally generated, organism-specific pathway maps [13]. Currently, there are seven categories for the KEGG pathways, including metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, organismal systems, human diseases, and drug development (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

GO analysis can be also performed directly via Gene Ontology Consortium (GOC) website (http://geneontology.org/docs/go-consortium/). In addition, STRING and FunRich are also applicable for GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses [5,7]. Furthermore, the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) classification system (http://pantherdb.org/about.jsp) [14] and the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) [15] are the other two main tools used for performing functional enrichment and pathway analyses. In addition to GO and KEGG, these tools can provide the comprehensive datasets from several other resources. PANTHER interoperates with other resources, including UniProt, Reactome (https://reactome.org/), InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/), and other databases [14]. DAVID also offers tissue expression information retrieved from Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/), disease information from DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org/), pathway information from WikiPathways (https://wikipathways.org/) and PathBank (https://www.pathbank.org/), and several other data from various resources [15]. Therefore, DAVID provides a wide variety of other additional useful information on top of the GO and KEGG knowledgebases [15].

For convenient data interpretation and visualization, Cytoscape platform has been developed and made available as an open-source software [6]. Several categories of a large number of plug-in apps (https://apps.cytoscape.org/) are provided inside Cytoscape, including but not limited to data visualization (Omics Visualizer), network generation (CluePedia and stringApp), network analysis (cytoHubba), clustering (MCODE), enrichment analysis (Clue GO), and pathway analysis (CyKEGGparser and KEGGscape) tools.

Moreover, several R packages have been developed and serve as the alternative means for free analysis and visualization of the PPI network (i.e., Path2PPI [16] and PrInCE [17]) and functional enrichment (i.e., pathfindR [18], Gogadget [19], and ViSEAGO [20]). However, the input identifier used for each tool varies, depending on the requirement of the tool. Generally, the Entrez Gene ID and UniProt ID can be used in almost all of the tools. However, the ID conversion may be required in some cases.

Roles of PPI network analysis and functional enrichment in kidney stone research

One of the major objectives in previous and recent kidney stone research is to address pathogenic and molecular mechanisms underlying KSD by using proteomics approach together with various computational tools.

Urinary proteins

Using functional and associated network analysis by IPA tool, the data have demonstrated that proteins found exclusively in urine from the stone formers potentially participate in metabolic processes associated with disease states [21]. GO analysis of urinary proteins derived from children stone formers has suggested the involvement of renal tubular dysfunction in these patients [22]. A recent study has shown the PPI network of differentially excreted urinary proteins from stone formers versus normal subjects by using InWeb PPI database and GeneNet Toolbox followed by selecting the backbone proteins for further functional enrichment [23]. The GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses by DAVID tool have revealed the disease processes and pathways associated with endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Such analyses have led to further in vitro and in vivo experiments to determine the critical biological events in the ER during kidney stone formation [23].

GO enrichment analysis of exosomal proteins derived from urine of normal subjects and stone formers using DAVID tool has shown that protein S100 family, including S100A8, S100A9 and S100A12 (enriched in stone formers’ exosomes), potentially participate in innate immunity and calcium binding [24]. Moreover, the study in patients with cystinuria and KSD has illustrated the PPI network of urinary proteins created by using Cytoscape tool [25]. GO enrichment analysis using DAVID tool has revealed that the higher-abundance urinary proteins in stone formers are involved mainly in stress response [25].

Stone matrix proteins

STRING analysis exploring the biological meaning of differentially expressed proteins in Escherichia coli collected from stone matrix and urine samples has illustrated three groups of proteins involved in RNA/protein metabolism, stress response, and carbohydrate metabolism [26]. Functional assay successfully verifies the involvement of an enzyme in carbohydrate metabolism formerly identified by the expression proteomics approach [26]. Applying the IPA tool to the proteome data derived from calcium oxalate (CaOx) stone matrix has found that the identified stone matrix proteins mainly localize in extracellular space, nucleus and cytoplasm, and has suggested an important role of renal cell injury during kidney stone formation [27].

In addition, analysis of the stone matrix proteome derived from two CaOx stone subtypes using IPA and Generic GO Term Mapper (https://go.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/GOTermMapper) has suggested immune response and tissue repair as the common functions of proteins found in both subtypes [28]. GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses of common matrix proteins collected from different studies using OmicShare tool (https://www.omicshare.com/tools/) have revealed that these proteins (e.g., S100A8, S100A9, uromodulin, albumin and osteopontin) are involved mainly in inflammation and immune response [29]. Moreover, network, GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses of matrix proteins extracted from uric acid stones can be done via Metacore tool (https://portal.genego.com/), AmiGO software (http://amigo.geneontology.org) and KEGG pathway database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html), respectively [30]. The data have demonstrated that matrix proteins in uric acid stones potentially participate in inflammatory process and lipid metabolism [30].

Randall’s plaque and renal papillary proteins

A recent study has applied multiple tools to define roles of key proteins in KSD. Multiple packages in R software, including “org.Hs.eg.db”, “clusterProfiler”, and “enrichplot”, have been used to analyze GO terms and KEGG pathways of the differentially expressed genes in Randall’s plaque versus normal papillary tissues [31]. Additionally, STRING tool has been used to construct the PPI network of proteins encoded by those genes and to explore the hub proteins [31]. Accordingly, uropontin (or osteopontin) encoded by SSP1, which has the higher expression level in Randall’s plaque tissue, has been identified as the top hub protein playing important role in immune cell infiltration [31].

Renal tubular cell proteins

A set of significantly altered proteins in MDCK renal tubular cells induced by low-dose CaOx monohydrate (COM) crystals have been analyzed by using STRING tool [32]. The results have shown the interaction between two significantly increased proteins, lamin A/C and nesprin-1, as well as the involvement of the altered proteins in several processes and functions, including regulation of metabolic process, DNA repair, cell migration, calcium ion binding, and cell death (Fig. 1A) [32]. Subsequent functional assays guided by computational analysis indicate the important roles of lamin A/C in cell proliferation, tissue repairing, and COM crystal adhesion on renal cells. Knockdown of lamin A/C expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA) causes decreases in expression levels of a number of COM crystal receptors, including enolase, leading to reduced number of the adhered crystals on renal tubular cells (Fig. 1B–D) [32]. These data highlight, for the first time, the significant role of lamin A/C in kidney stone formation processes.

Fig. 1.

PPI network analysis and functional enrichment lead to defining the novel role of lamin A/C in kidney stone formation processes. (A): PPI network and functional category of significantly altered proteins in renal cells induced by low-dose COM crystals identified by expression proteomics. (B): Effect of siRNA specific to lamin A/C (si-LMNA) on expression level of enolase, one of the COM crystal receptors on renal cells, as compared with the control siRNA (si-Control) without or with oxalate (a known inducer of enolase). (C and D): Effect of si-LMNA on crystal-binding capability of renal cells compared with si-Control without or with oxalate. ∗p < 0.05 vs. control; #p < 0.05 vs. si-Control; †p < 0.05 vs. si-LMNA. Modified with permission from Ref. [32].

Along the same line, differential expression of cellular proteome of HK-2 renal tubular cells induced by stone-derived crystals has been analyzed using GOATOOLS (https://github.com/tanghaibao/goatools), KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/), and STRING tools [33]. The data from these computational analyses have provided evidence that COM crystals affect the dynamics of cell structure and actin cytoskeletal assembly [33]. Moreover, a recent study performing STRING network and functional analyses of significantly altered proteins in HK-2 cells induced by COM crystals has found that the upregulated proteins are mainly involved in calcium-binding, stress response, apoptosis, and inflammation [34].

PPI network analysis by using STRING tool has also displayed the downregulated protein, α-tubulin, as one of the central nodes of PPI among differentially expressed proteins induced by high-dose COM crystals (Fig. 2A) [35]. Both of its direct interaction with vimentin and indirect interaction with annexin A2 can be confirmed by immunofluorescence stainings (Fig. 2B). Overexpression of α-tubulin can preserve not only its own level but also levels of these two interacting partners after exposure to COM crystals. The network analysis has also led to functional investigations on the role of α-tubulin in kidney stone formation mechanisms [35]. The results from several subsequent assays have shown the protective roles of α-tubulin, as its overexpression enhances cell proliferation and tissue repairing activity, while prevents cell death and crystal-cell adhesion [35]. STRING network analysis and functional prediction of a set of altered cellular proteins in MDCK cells induced by high-dose COM crystals have revealed that those altered proteins are involved in oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, cell proliferation, wound healing, and cellular junction complex and integrity (Fig. 3) [36]. All of these cellular functions affected by COM crystals can be confirmed experimentally by various functional assays [36].

Fig. 2.

PPI network of significantly altered proteins in CaOx-treated renal cells and co-localization of α-tubulin (Tuba1a) with vimentin (Vim) and annexin A2 (Anxa2). (A): PPI network showing Tuba1a as one of the central nodes that has direct interaction with Vim and indirect interaction with Anxa2 in CaOx-treated renal cells. (B): Immunofluorescence assay confirming co-localization (in yellow) of α-tubulin (in red) with both vimentin (in green) and annexin A2 (in green). Modified with permission from Ref. [35].

Fig. 3.

PPI network analysis and functional enrichment of 52 significantly altered proteins in renal cells induced by high-dose COM crystals. The PPI network highlights the involvement of oxidative stress and mitochondrial function, cell proliferation and would healing, and cellular junctional complex and integrity induced by COM crystals. Modified with permission from Ref. [36].

PANTHER and STRING tools have been employed in a more comprehensive study using proteomics datasets from different CaOx crystal types (COM vs. CaOx dihydrate or COD) and doses (low-dose vs. high-dose) to analyze cellular responses [37]. The analyses have highlighted the type- and dose-specific cellular responses to CaOx crystals (Fig. 4) [37]. Interestingly, the set of proteins exclusively altered by COM crystals are involved in cell integrity and adhesion, indicating the potential pathogenicity of COM crystals [37].

Fig. 4.

Comparative analyses of significantly altered proteins in renal cells induced by low-dose and high-dose of COM and COD crystals. (A): The number of significantly altered proteins induced by each type/dose of crystals. (B): Venn diagram illustrating numbers of common and unique altered proteins induced by each type/dose of crystals. (C) and (D): Heat-map representing number of the altered proteins within each functional group and subcellular localization, respectively. COM 100 = COM at 100 μg/ml; COD 100 = COD at 100 μg/ml; COM 1000 = COM at 1000 μg/ml; COD 1000 = COM at 1000 μg/ml. Modified with permission from Ref. [37].

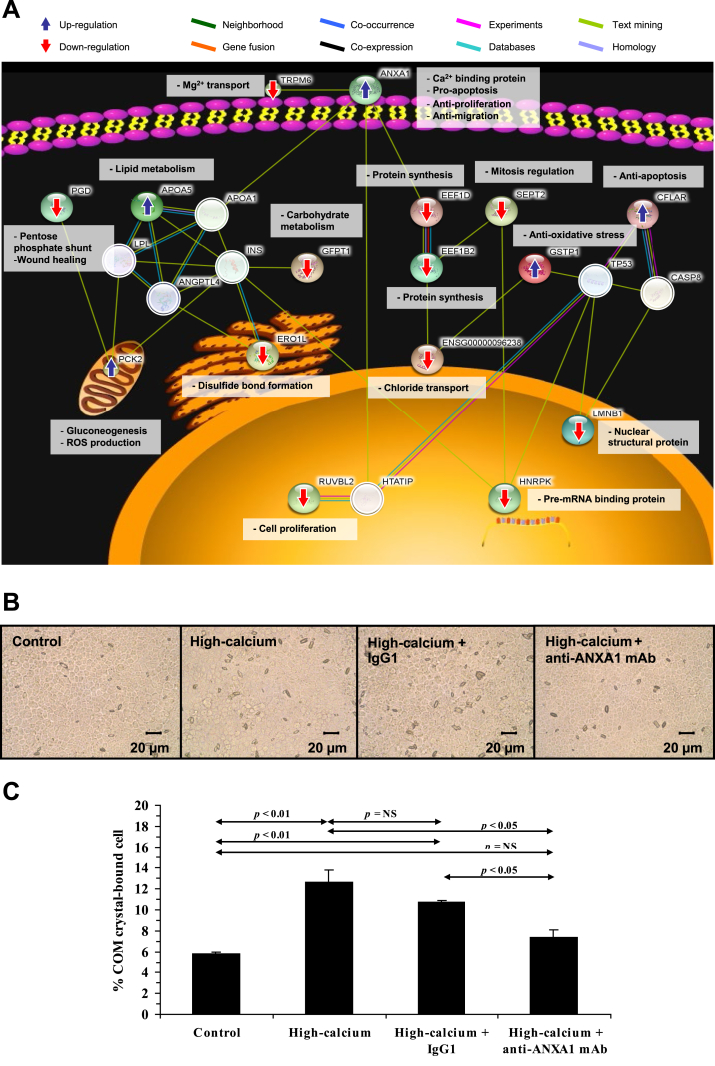

Several factors have been reported as the risks for kidney stone formation. PPI network analysis and functional prediction have been utilized to help understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of those risk factors on KSD pathogenesis. A number of studies have focused on influences of hypercalciuria and hyperoxaluria, which are the main risk factors for calcium stones [38]. After differential expression proteomics study in high-calcium-treated MDCK renal cells, PPI network analysis and functional enrichment using STRING tool have found that the upregulated proteins are involved in calcium ion binding and anti-proliferation process, whereas the downregulated proteins participate in cell proliferation, pre-mRNA processing, mitosis regulation, and protein synthesis (Fig. 5A) [39]. Subsequent experiments confirm that high-calcium condition enhances COM crystal-binding capability (Fig. 5B and C) but suppresses cell proliferation and wound healing activity of the renal cells [39].

Fig. 5.

PPI network analysis and functional enrichment lead to functional investigations of mechanisms underlying high-calcium induced kidney stone formation. (A): PPI network, subcellular localization and functional category of the significantly altered proteins in renal cells induced by high-calcium. (B and C): COM crystal-cell adhesion assay after high-calcium treatment without or with neutralization by non-specific IgG1 or specific anti-ANXA1 (annexin A1) monoclonal antibody (mAb). NS = not statistically significant. Modified with permission from Ref. [39].

The analyses of significantly altered proteins in MDCK cells induced by high-oxalate condition have revealed that the upregulated proteins are involved in Rho signaling pathway, protein kinase A activity, actin polymerization, stress response and COM crystal binding, whereas the downregulated proteins are involved in transcriptional regulation and energy production [40]. Experimental study confirms the enhancing effect of high-oxalate condition on COM crystal binding, whereas neutralization of surface α-enolase (one of the up-regulated proteins) by its specific antibody can reduce such enhancement of crystal binding on the renal cells [40].

Hyperuricosuria is another aggravating factor for kidney stone formation. Alterations in MDCK cellular proteome by high uric acid have been investigated [41]. STRING, ClueGO, and PANTHER tools have been utilized to obtain biological meanings of the altered proteins. The analyses have revealed their involvement in several biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular compartments (Fig. 6) [41]. Following these predictions guided by computational analyses, various functional assays confirm that high uric acid enhances intracellular ATP production, tissue repairing activity, and COM crystal-binding capability of the cells, suggesting the association of hyperuricosuria in mixed stone formation [41].

Fig. 6.

PPI network analysis and functional enrichment of significantly altered proteins in renal cells induced by high uric acid. (A): PPI network and functional category of the significantly altered proteins in renal cells induced by high uric acid. (B): Detailed information of functional annotations of all the significantly altered proteins based on GO classification, including biological process, molecular function, cellular component, and protein class. Modified with permission from Ref. [41].

Mitochondrial proteins

IPA tool has been utilized to analyze changes in mitochondrial proteome in renal epithelial cells after COM crystal treatment [42]. The altered mitochondrial proteins have been predicted to get involved in carbohydrate metabolism, organismal functions and gene expression, suggesting the defects in energy production and mitochondrial dysfunction during initial stone formation step [42]. Remarkably, functional assays can confirm such prediction and show that COM crystals cause increment of oxidatively modified proteins, indicating the loss of reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulation by mitochondria [42].

Cellular and secretory proteins from immune cells

Analysis of macrophage cellular proteome by STRING tool has found three groups of the altered proteins induced by COM crystals, including cytoskeletal proteins, chaperones and metabolic proteins [43]. Interestingly, the STRING network has also shown interactions of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) with β-actin and α-tubulin (Fig. 7A). Experimental validation has confirmed the interactions of HSP90 with both β-actin and α-tubulin (Fig. 7B and C). Interestingly, only its interaction with β-actin is associated with phagosome formation and phagocytic activity of macrophages (Fig. 7B and C) [43]. Additionally, analysis of secretome from monocytes by IPA tool has suggested that the altered secretory proteins induced by COM crystals play roles in cell survival and immune response, indicating the progression of renal inflammation during kidney stone formation processes [44]. GO enrichment analysis of exosomal proteins derived from COM crystal-treated macrophages by FunRich tool has found that the altered exosomal proteins are involved in several biological processes, including signal transduction and cell communications [45]. Thereafter, the involved functions guided by STRING network analysis, including interleukin-8 production, crystal invasion through extracellular matrix (ECM) and neutrophil migration, can be successfully verified [45]. Additionally, functional enrichment analysis of secretome derived from COM crystal-treated macrophages using g:GOSt and STRING tools has suggested their potential functions in fibroblast activation, which are also validated successfully by various experimental assays [46].

Fig. 7.

PPI network analysis and functional enrichment lead to defining the important role of PPI between HSP90 and β-actin in phagosome formation in macrophages induced by COM crystals. (A): PPI network and functional category of the altered proteins in macrophages induced by COM crystals. (B and C): Immunofluorescence stainings to demonstrate co-localization (in yellow) of HSP90 (in red) with F-actin (in green) and α-tubulin (in green), respectively. However, only the HSP90/F-actin co-localization is found on the phagosome (labelled with arrow head) membrane surrounding COM crystal. Modified with permission from Ref. [43].

Effects of sex hormones on KSD

The prevalence of KSD is generally higher in males than females around the globe [47]. In the United States, its prevalence is approximately 11% in males and 7% in females [48]. Additionally, the KSD incidence increases in postmenopausal females [49]. Therefore, sex hormones have been considered to affect kidney stone pathogenesis. Proteomics studies have been done to identify sets of altered proteins in renal tubular cells after testosterone [50] and estrogen [51] treatments. Applying STRING tool for PPI network analysis and functional prediction of those altered proteins, the data have revealed one of the upregulated proteins, α-enolase, as the central node of PPI in the testosterone study [50]. Additionally, the cellular localization of α-enolase from functional enrichment analysis is cell membrane, indicating the potential role of this protein as the COM crystal receptor to promote kidney stone formation [50]. The role for α-enolase as the COM crystal receptor has been confirmed by crystal assays and neutralization by its specific antibody [50,52]. These data indicate the promoting effects of testosterone on kidney stone formation. On the other hand, PPI network analysis and function prediction by using STRING tool has found that the significantly altered proteins induced by estrogen participate mainly in metabolic process, binding/receptor and migration/healing [51]. The computational prediction has led to functional assays, which confirm the effects of estrogen on alleviating COM crystal-cell adhesion and ATP overproduction as well as improving wound healing activity [51]. These data indicate the protective roles of estrogen against kidney stone formation.

Defining new therapeutic targets and preventive strategies

Computational analyses of PPI network and functional enrichment also provide benefits to define cellular/molecular mechanisms of the therapeutic/preventive effects of various anti-lithogenic agents. The possible molecular mechanism underlying inhibitory effect of ketotifen against CaOx KSD has been investigated in a rat model by computational analysis of GO enrichment and KEGG pathway for the downregulated proteins, including osteopontin, CD44 and fibronectin [53]. Several packages in R software, including “Stringi” and “clusterProfiler”, have been applied to demonstrate that the downregulated proteins are involved in ECM-receptor interaction pathway. Additionally, the data have demonstrated that ketotifen also affects integrin and ROS synthesis [53].

Adherence of crystals onto renal epithelial membrane surfaces is considered as one of the crucial steps for kidney stone formation. Defining crystal receptors on the surfaces of renal cells may lead to development of new preventive strategy to block crystal binding onto the cells. Computational approach is very helpful to identify and characterize crystal-binding proteins or crystal receptors. In a previous study, chemico–protein interactions network analysis by using STICH tool has found that α-enolase directly interacts with calcium ion, confirming its important role as a COM crystal receptor on renal tubular cell surface [52].

In a recent study identifying the interacting partners of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase 2 (PMCA2) by IP-MS, STRING network analysis has revealed a large number of the novel PMCA2-interacting partners [54]. Some of these novel interacting partners have been confirmed by immunoassay to demonstrate their colocalization with PMCA2 (Fig. 8A–D) Additionally, PANTHER analysis has indicated that the predominant GO molecular function for the novel partners is binding activity, including protein binding and calcium ion binding (Fig. 8E) [54]. This evidence has led to further functional assays confirming the role of PMCA2 as one of the COM crystal-binding proteins on apical membranes of renal tubular cells (Fig. 8F and G). Subsequent additional assays strengthen that PMCA2 serves as a novel COM crystal receptor [54].

Fig. 8.

PPI network analysis and functional enrichment lead to defining PMCA2 as a novel COM crystal receptor. (A–D): Experimental confirmation of co-localization (in yellow) of PMCA2 (in red) with its known and novel interacting partners (in green). The co-localization is also indicated by small black arrows on the spectra and significant correlation coefficient (r) of the upper right plot of immunofluorescence intensities. (E): GO analysis of PMCA2-interacting partners revealing binding activity as the main functional category. (F): COM crystal-protein binding assay followed by Western blotting to confirm the presence of PMCA2 in whole cell lysate, apical membranes, and COM crystal-bound fraction. (G): COM crystal-protein binding assay followed by immunofluorescence staining confirming the binding of PMCA2 (in red) on COM crystal surface, whereas the samples stained with non-specific IgG and anti-gp135 antibody serves as the negative controls. Modified with permission from Ref. [54].

In another study, the STRING and SAINT interaction scores have been employed to strengthen the results obtained from TAP-MS to identify HSP90-interacting partners [55]. Most of the experimentally identified partners have the high interacting scores. Analysis for the functional relevance of HSP90 and its interacting partners has revealed that proteins in this interacting complex are involved mainly in signal transduction, cytoskeleton assembly, protein transport, and chaperoning [55]. GO molecular function analysis using PANTHER tool has found that their main molecular function is binding (to several compounds, including anions) [55]. Interestingly, HSP90 and a number of its interacting partners (i.e., α-tubulin, β-actin, vimentin and calpain-1) have been identified as the potential COM crystal receptors [56,57]. Knockdown of HSP90 expression by siRNA decreases levels of HSP90 and all of these interacting COM crystal receptors as well as their association, resulting in the reduction of crystal-cell adhesion [55].

All of these data underscore the potential of PPI network analysis and function enrichment via computational biotechnology to address molecular mechanism underlying the anti-lithogenic activity of a candidate compound. Moreover, this computational approach also leads to identification and/or confirmation of the COM crystal receptors that may serve as the new targets for further development of the anti-lithogenic agents.

Summary and outlook

Computation-based approach has been widely applied to several studies to investigate mechanisms of kidney stone formation and to define new therapeutic targets and preventive strategies. Analyses of PPI network and functional enrichment of the proteins identified from urine and stone matrix samples of the stone formers and cells after various interventions have provided a wealth of useful information to better understand biological cascades and disease pathways after crystal-cell interactions and ultimately kidney stone formation processes. Moreover, defining the CaOx crystal receptors and anti-lithogenic agents via experimental studies together with computational approach may lead to development of new therapeutic targets and preventive strategies for better therapeutic outcome of KSD management.

Fortunately, several computational tools are available for the aforementioned analyses, e.g., STRING, FunRich, IPA, DAVID, and PANTHER tools. Combining multiple tools can be done to enhance and strengthen the analyses. However, each tool provides similar and different angles of the data coverage. Therefore, the most challenging issue for PPI network analysis and functional enrichment of proteins involved in KSD is selection of the appropriate tool(s) for each dataset to address the objectives of each study. Although the resources used for PPI network analysis and functional enrichment of human genes/proteins are more complete than those of other organisms, analyses of such data in other species can be done by transferring the evidence from human species. For example, a number of tools such as PHI-base (the pathogen-host interactions database) (http://www.phi-base.org/) [58] and PATRIC (https://www.patricbrc.org/) [59] have been introduced to construct the pathogen-host interactions network for studying the interplays between organisms and humans in infectious diseases [60]. This approach may be useful to study the association between urinary tract infection (UTI) and formation of infection kidney stones. Therefore, applying computation-based approach for analysis of pathogen-host interactions network should be further considered to obtain more solid evidence for KSD related to or caused by UTI.

In addition to the mass spectrometry-based proteomics approach, transcriptomics is another powerful tool to obtain expression data for subsequent PPI network and function enrichment analyses. For example, a previous study has employed a microarray-based transcriptomics approach to identify altered genes in kidneys of hydroxy-l-proline-induced hyperoxaluric rats [61]. GO pathway analysis using the DAVID tool reveals >20 pathways involved, particularly NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasome pathway associated with CaOx crystal-induced ROS overproduction [61]. This approach also reveals altered genes involved in osteogenic transformation of the renal epithelial cells in these hyperoxaluric rats [62]. Moreover, the microarray-based transcriptome analysis also shows differential sets of genes, particularly those related to inflammation and injury, expressed in hyperoxaluric versus CaOx stone-forming rats induced by EG [63].

Furthermore, several studies have also applied the computational approach to address the roles for micro RNAs (miRNAs) in KSD pathogenesis, including in vivo analysis of differential miRNA expression in genetically hypercalciuric stone-forming rats using Gene Cloud of Biotechnology Information (GCBI) working platform [64]. Additionally, DAVID tool and GOC website have been applied to perform GO and KEGG pathway analyses of altered miRNAs in EG-induced CaOx stone-forming rats [65,66]. DAVID tool has been also applied for studying the GO terms and KEGG pathways involved in expression variation profiles of long-non-coding RNA (lncRNA), miRNA and mRNA in the urine samples from CaOx stone formers [67]. The analyses have provided the potential functions that may be linked between the expression of miRNAs and KSD pathogenesis. However, the experimental approaches are required to further validate the prediction from such computational analyses. Having done so, the development of new therapeutic targets and preventive strategies via lncRNA, miRNA and mRNA will be more feasible.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Mahidol University (grant no. N42A650371).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Boys E.L., Liu J., Robinson P.J., Reddel R.R. Clinical applications of mass spectrometry-based proteomics in cancer: where are we? Proteomics. 2022 doi: 10.1002/pmic.202200238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abyadeh M., Gupta V., Chitranshi N., Gupta V., Wu Y., Saks D., et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in alzheimer’s disease - a proteomics perspective. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2021;18(4):295–304. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2021.1918550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peerapen P., Thongboonkerd V. Kidney stone proteomics: an update and perspectives. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2021;18(7):557–569. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2021.1962301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S., Wu R., Lu J., Jiang Y., Huang T., Cai Y.D. Protein-protein interaction networks as miners of biological discovery. Proteomics. 2022;22(15–16) doi: 10.1002/pmic.202100190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Nastou K.C., Lyon D., Kirsch R., Pyysalo S., et al. The string database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Gorodkin J., Jensen L.J. Cytoscape stringapp: network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(2):623–632. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonseka P., Pathan M., Chitti S.V., Kang T., Mathivanan S. Funrich enables enrichment analysis of omics datasets. J Mol Biol. 2021;433(11) doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.166747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer A., Green J., Pollard J., Jr., Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(4):523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi H., Larsen B., Lin Z.Y., Breitkreutz A., Mellacheruvu D., Fermin D., et al. Saint: probabilistic scoring of affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat Methods. 2011;8(1):70–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi H., Glatter T., Gstaiger M., Nesvizhskii A.I. Saint-ms1: protein-protein interaction scoring using label-free intensity data in affinity purification-mass spectrometry experiments. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(4):2619–2624. doi: 10.1021/pr201185r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szklarczyk D., Santos A., von Mering C., Jensen L.J., Bork P., Kuhn M. Stitch 5: augmenting protein-chemical interaction networks with tissue and affinity data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D380–D384. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gene Ontology C. The gene ontology resource: enriching a gold mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D325–D334. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanehisa M., Sato Y., Kawashima M. Kegg mapping tools for uncovering hidden features in biological data. Protein Sci. 2022;31(1):47–53. doi: 10.1002/pro.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mi H., Muruganujan A., Ebert D., Huang X., Thomas P.D. Panther version 14: more genomes, a new panther go-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D419–D426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman B.T., Hao M., Qiu J., Jiao X., Baseler M.W., Lane H.C., et al. David: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W216–W221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philipp O., Osiewacz H.D., Koch I. Path2ppi: an r package to predict protein-protein interaction networks for a set of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(9):1427–1429. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skinnider M.A., Cai C., Stacey R.G., Foster L.J. Prince: an r/bioconductor package for protein-protein interaction network inference from co-fractionation mass spectrometry data. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:2775–2777. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulgen E., Ozisik O., Sezerman O.U. Pathfindr: an r package for comprehensive identification of enriched pathways in omics data through active subnetworks. Front Genet. 2019;10:858. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nota B. Gogadget: an r package for interpretation and visualization of go enrichment results. Mol Inform. 2017;36(5–6) doi: 10.1002/minf.201600132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brionne A., Juanchich A., Hennequet-Antier C. Viseago: A bioconductor package for clustering biological functions using gene ontology and semantic similarity. BioData Min. 2019;12:16. doi: 10.1186/s13040-019-0204-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright C.A., Howles S., Trudgian D.C., Kessler B.M., Reynard J.M., Noble J.G., et al. Label-free quantitative proteomics reveals differentially regulated proteins influencing urolithiasis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(8) doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.005686. M110 005686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovacevic L., Lu H., Caruso J.A., Lakshmanan Y. Renal tubular dysfunction in pediatric urolithiasis: proteomic evidence. Urology. 2016;92:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang B., Lu X., Li Y., Li Y., Yu D., Zhang W., et al. A proteomic network approach across the kidney stone disease reveals endoplasmic reticulum stress and crystal-cell interaction in the kidney. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/9307256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Q., Sun Y., Yang Y., Li C., Zhang J., Wang S. Quantitative proteomic analysis of urinary exosomes in kidney stone patients. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9(4):1572–1584. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovacevic L., Lu H., Goldfarb D.S., Lakshmanan Y., Caruso J.A. Urine proteomic analysis in cystinuric children with renal stones. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11(4):217 e1–217 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tavichakorntrakool R., Boonsiri P., Prasongwatana V., Lulitanond A., Wongkham C., Thongboonkerd V. Differential colony size, cell length, and cellular proteome of escherichia coli isolated from urine vs. Stone nidus of kidney stone patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;466:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wesson J.A., Kolbach-Mandel A.M., Hoffmann B.R., Davis C., Mandel N.S. Selective protein enrichment in calcium oxalate stone matrix: a window to pathogenesis? Urolithiasis. 2019;47(6):521–532. doi: 10.1007/s00240-019-01131-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witzmann F.A., Evan A.P., Coe F.L., Worcester E.M., Lingeman J.E., Williams J.C., Jr. Label-free proteomic methodology for the analysis of human kidney stone matrix composition. Proteome Sci. 2016;14:4. doi: 10.1186/s12953-016-0093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y., Hong S., Li C., Zhang J., Hu H., Chen X., et al. Proteomic analysis reveals some common proteins in the kidney stone matrix. PeerJ. 2021;9 doi: 10.7717/peerj.11872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jou Y.C., Fang C.Y., Chen S.Y., Chen F.H., Cheng M.C., Shen C.H., et al. Proteomic study of renal uric acid stone. Urology. 2012;80(2):260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong S.Y., Xia Q.D., Xu J.Z., Liu C.Q., Sun J.X., Xun Y., et al. Identification of the pivotal role of spp1 in kidney stone disease based on multiple bioinformatics analysis. BMC Med Genom. 2022;15(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12920-022-01157-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pongsakul N., Vinaiphat A., Chanchaem P., Fong-ngern K., Thongboonkerd V. Lamin a/c in renal tubular cells is important for tissue repair, cell proliferation, and calcium oxalate crystal adhesion, and is associated with potential crystal receptors. Faseb J. 2016;30(10):3368–3377. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600426R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z., Li M.X., Xu C.Z., Zhang Y., Deng Q., Sun R., et al. Comprehensive study of altered proteomic landscape in proximal renal tubular epithelial cells in response to calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals. BMC Urol. 2020;20(1):136. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00709-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narula S., Tandon S., Kumar D., Varshney S., Adlakha K., Sengupta S., et al. Human kidney stone matrix proteins alleviate hyperoxaluria induced renal stress by targeting cell-crystal interactions. Life Sci. 2020;262 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manissorn J., Khamchun S., Vinaiphat A., Thongboonkerd V. Alpha-tubulin enhanced renal tubular cell proliferation and tissue repair but reduced cell death and cell-crystal adhesion. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep28808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peerapen P., Chaiyarit S., Thongboonkerd V. Protein network analysis and functional studies of calcium oxalate crystal-induced cytotoxicity in renal tubular epithelial cells. Proteomics. 2018;18(8) doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinaiphat A., Aluksanasuwan S., Manissorn J., Sutthimethakorn S., Thongboonkerd V. Response of renal tubular cells to differential types and doses of calcium oxalate crystals: integrative proteome network analysis and functional investigations. Proteomics. 2017;17(15–16) doi: 10.1002/pmic.201700192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alelign T., Petros B. Kidney stone disease: an update on current concepts. Adv Urol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3068365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chutipongtanate S., Fong-ngern K., Peerapen P., Thongboonkerd V. High calcium enhances calcium oxalate crystal binding capacity of renal tubular cells via increased surface annexin a1 but impairs their proliferation and healing. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(7):3650–3663. doi: 10.1021/pr3000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanlaya R., Fong-ngern K., Thongboonkerd V. Cellular adaptive response of distal renal tubular cells to high-oxalate environment highlights surface alpha-enolase as the enhancer of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal adhesion. J Proteomics. 2013;80:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutthimethakorn S., Thongboonkerd V. Effects of high-dose uric acid on cellular proteome, intracellular atp, tissue repairing capability and calcium oxalate crystal-binding capability of renal tubular cells: implications to hyperuricosuria-induced kidney stone disease. Chem Biol Interact. 2020;331 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaiyarit S., Thongboonkerd V. Changes in mitochondrial proteome of renal tubular cells induced by calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal adhesion and internalization are related to mitochondrial dysfunction. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(6):3269–3280. doi: 10.1021/pr300018c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singhto N., Sintiprungrat K., Thongboonkerd V. Alterations in macrophage cellular proteome induced by calcium oxalate crystals: the association of hsp90 and f-actin is important for phagosome formation. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(8):3561–3572. doi: 10.1021/pr4004097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sintiprungrat K., Singhto N., Thongboonkerd V. Characterization of calcium oxalate crystal-induced changes in the secretome of u937 human monocytes. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12(3):879–889. doi: 10.1039/c5mb00728c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singhto N., Thongboonkerd V. Exosomes derived from calcium oxalate-exposed macrophages enhance il-8 production from renal cells, neutrophil migration and crystal invasion through extracellular matrix. J Proteomics. 2018;185:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoodee S., Noonin C., Sueksakit K., Kanlaya R., Chaiyarit S., Peerapen P., et al. Effects of secretome derived from macrophages exposed to calcium oxalate crystals on renal fibroblast activation. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):959. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferraro P.M., Taylor E.N., Curhan G.C. Factors associated with sex differences in the risk of kidney stones. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2023;38(1):177–183. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tundo G., Vollstedt A., Meeks W., Pais V. Beyond prevalence: annual cumulative incidence of kidney stones in the United States. J Urol. 2021;205(6):1704–1709. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prochaska M., Taylor E.N., Curhan G. Menopause and risk of kidney stones. J Urol. 2018;200(4):823–828. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.04.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Changtong C., Peerapen P., Khamchun S., Fong-ngern K., Chutipongtanate S., Thongboonkerd V. In vitro evidence of the promoting effect of testosterone in kidney stone disease: a proteomics approach and functional validation. J Proteomics. 2016;144:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peerapen P., Thongboonkerd V. Protective cellular mechanism of estrogen against kidney stone formation: a proteomics approach and functional validation. Proteomics. 2019;19(19) doi: 10.1002/pmic.201900095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fong-ngern K., Thongboonkerd V. Alpha-enolase on apical surface of renal tubular epithelial cells serves as a calcium oxalate crystal receptor. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep36103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Z., Wang G., Yang B., Li P., Yang T., Wu Y., et al. Mechanism of ketotifen fumarate inhibiting renal calcium oxalate stone formation in sd rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vinaiphat A., Thongboonkerd V. Characterizations of pmca2-interacting complex and its role as a calcium oxalate crystal-binding protein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(8):1461–1482. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2699-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manissorn J., Singhto N., Thongboonkerd V. Characterizations of hsp90-interacting complex in renal cells using tandem affinity purification and its potential role in kidney stone formation. Proteomics. 2018;18(24) doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fong-ngern K., Sueksakit, Thongboonkerd V. Surface heat shock protein 90 serves as a potential receptor for calcium oxalate crystal on apical membrane of renal tubular epithelial cells. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2016;21(4):463–474. doi: 10.1007/s00775-016-1355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fong-ngern K., Peerapen P., Sinchaikul S., Chen S.T., Thongboonkerd V. Large-scale identification of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystal-binding proteins on apical membrane of distal renal tubular epithelial cells. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(10):4463–4477. doi: 10.1021/pr2006878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urban M., Cuzick A., Seager J., Wood V., Rutherford K., Venkatesh S.Y., et al. Phi-base in 2022: a multi-species phenotype database for pathogen-host interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D837–D847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davis J.J., Wattam A.R., Aziz R.K., Brettin T., Butler R., Butler R.M., et al. The patric bioinformatics resource center: expanding data and analysis capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D606–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mulder N.J., Akinola R.O., Mazandu G.K., Rapanoel H. Using biological networks to improve our understanding of infectious diseases. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2014;11(18):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joshi S., Wang W., Peck A.B., Khan S.R. Activation of the nlrp3 inflammasome in association with calcium oxalate crystal induced reactive oxygen species in kidneys. J Urol. 2015;193(5):1684–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.11.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joshi S., Clapp W.L., Wang W., Khan S.R. Osteogenic changes in kidneys of hyperoxaluric rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(9):2000–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joshi S., Wang W., Khan S.R. Transcriptional study of hyperoxaluria and calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis in male rats: inflammatory changes are mainly associated with crystal deposition. PLoS One. 2017;12(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu Y., Qin B., Hu H., Zhang J., Wang Y., Wang Q., et al. Integrative microrna-gene expression network analysis in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rat kidney. PeerJ. 2016;4 doi: 10.7717/peerj.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lan C., Chen D., Liang X., Huang J., Zeng T., Duan X., et al. Integrative analysis of mirna and mrna expression profiles in calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis rat model. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/8306736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Z., Jiang H., Yang J., Wang T., Ding Y., Liu J., et al. Analysis of altered microrna expression profiles in the kidney tissues of ethylene glycol-induced hyperoxaluric rats. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(5):4650–4658. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liang X., Lai Y., Wu W., Chen D., Zhong F., Huang J., et al. Lncrna-mirna-mrna expression variation profile in the urine of calcium oxalate stone patients. BMC Med Genom. 2019;12(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]