INTRODUCTION

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP1RA) are recommended glucose-lowering therapies over sulfonylureas.1 Unlike SGLT2i and GLP1RA, sulfonylureas do not improve cardiovascular/kidney outcomes, and confer a higher risk of hypoglycemia. Although sulfonylurea use in the USA has declined over time, almost 25% of adults with diabetes still used sulfonylureas in 2015–2018.2

Second-generation sulfonylureas (e.g., glyburide, glimepiride, and glipizide) carry a lower risk of hypoglycemia and are recommended over first-generation agents.1 Moreover, cardiovascular and/or hypoglycemic risks differ within generation. While clinical trials showed cardiovascular safety of glimepiride,3 glyburide may increase cardiovascular risk via inhibitory effect on myocardial and vascular KATP channels. A French study showed that arrhythmias, ischemic complications, and in-hospital mortality were higher with glyburide than with gliclazide (unavailable in the USA) or glimepiride.4 A German study reported that risk of severe hypoglycemia was higher with glyburide than with glimepiride.5 However, changes in the types of sulfonylureas used by adults with diabetes remain uncharacterized.

METHODS

We conducted cross-sectional analyses of data from the 1999 to 2020 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to characterize national trends in the use of each sulfonylurea type among non-pregnant US adults (age ≥20 years) with self-reported diagnosed diabetes.

Medication use was ascertained via questionnaire asking if participants had taken any prescription medications in the past 30 days. Sulfonylureas included first-generation (chlorpropamide and tolazamide) and second-generation (glipizide, glimepiride, and glyburide) agents.

Among adults with diabetes (n = 7209), we estimated the prevalence of any sulfonylurea use as well as individual agent use over time. Among sulfonylurea users (n = 2397), we quantified proportional shares of each sulfonylurea type over time. We repeated analyses by age (≥65 and <65 years). All analyses were weighted, accounting for the complex survey design of NHANES. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

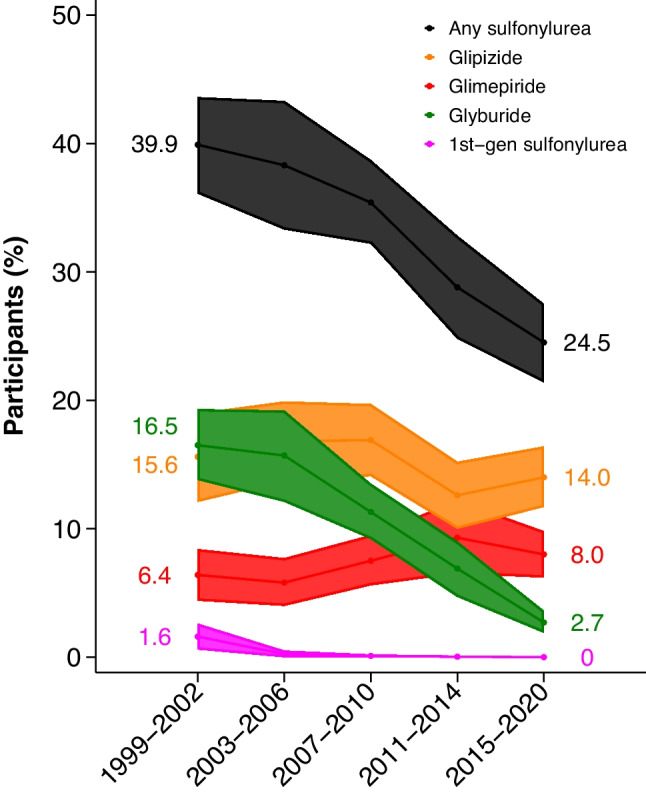

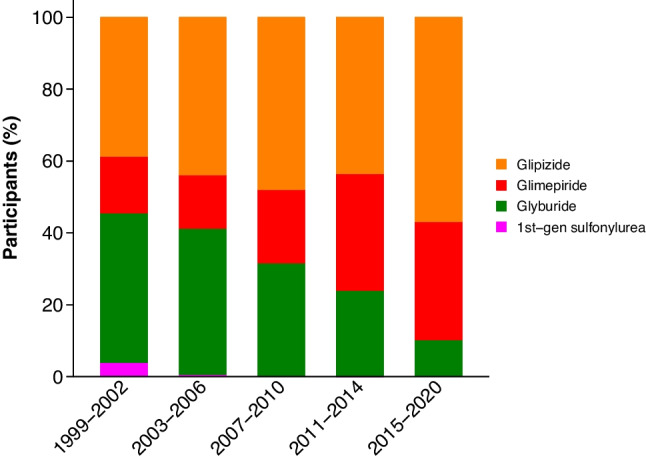

Among US adults with diagnosed diabetes (corresponding to 19 million persons in 2009–2010), the mean age was 60 (SE, 0.2) years and 50% were women. Sulfonylurea use declined significantly from 39.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 36.1–43.6%) in 1999–2002 to 24.5% (95% CI, 21.4–27.5%) in 2015–2020. First-generation sulfonylurea use was uncommon: 1.6% (95% CI, 0.6–2.6%) in 1999–2002 and 0% after 2015. Among second-generation sulfonylureas, only glyburide use decreased significantly, from 16.5% (95% CI, 13.8–19.3%) in 1999–2002 to 2.7% (95% CI, 1.9–3.6%) in 2015–2020, corresponding to a population estimate of 746,000 (95% CI, 516,000–976,000) (Fig. 1). Consequently, among sulfonylurea users, glyburide was the least used second-generation sulfonylurea (10.2%, 95% CI: 7.2–13.1%) in 2015–2020 after being the most used (41.6%, 95% CI: 35.4–47.8%) in 1999–2002. In 2015–2020, glipizide was the most commonly used sulfonylurea (56.9%, 95% CI: 50.4–63.3%) (Fig. 2). Similar trends were observed in adults ≥65 and <65 years, but sulfonylurea was more frequently used in older adults (29.5% [95% CI, 24.8–34.2%] for ≥65 years and 20.7% [95% CI, 17.2–24.2%] for <65 years in 2015–2020).

Figure 1.

Trends in sulfonylurea use among US adults with diagnosed diabetes, NHANES 1999 to 2020. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. First-generation sulfonylurea includes chlorpropamide and tolazamide.

Figure 2.

Trends in shares of sulfonylurea types among sulfonylurea users, NHANES 1999 to 2020. First-generation sulfonylurea includes chlorpropamide and tolazamide.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that, as recommended in guidelines,1 first-generation sulfonylureas are seldom used in the USA. Given the higher cardiovascular and hypoglycemic risk with the second-generation sulfonylurea glyburide, it is also encouraging to observe decreased use of this medication over time, with less than 3% of US adults with diabetes using glyburide in recent years. Nonetheless, ~750,000 individuals still use glyburide, despite the widespread availability of safer sulfonylureas and other recommended classes of antidiabetic medications. Indeed, in 2019, there were 1.7 million prescriptions for glyburide in the USA.6 When sulfonylureas are preferred due to medication costs, both glipizide and glimepiride are similarly or even less expensive than glyburide, which may result in cost savings for patients and the health care system. The more frequent use of sulfonylurea among older adults than younger adults in this study deserves attention, considering the higher cardiovascular and hypoglycemic risks in older adults. Our study has limitations. Self-reported use of prescription medications in NHANES was not always verified with medication containers. Formulations of glyburide (i.e., micronized or non-micronized) and glipizide (i.e., immediate or extended release) could not be examined.

In summary, our data suggest that sulfonylurea use has declined over the past two decades, driven mainly by decreased use of glyburide. Nonetheless, ~750,000 adults with diabetes currently use this medication, despite the availability of safer and equally cost-saving alternatives.

Acknowledgements

J.S. was supported by NIH/NIDDK grant K01DK121825. J.B. E-T was supported by NIH/NHLBI grant K23 HL153774. E.S. was supported by NIH/NHLBI grant K24 HL152440. M.E.G. was supported by R01DK115534 and K24HL155861.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/3/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s11606-023-08445-4

References

- 1.ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Supplement_1):S140-S57. 10.2337/dc23-S009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Fang M, Wang D, Coresh J, Selvin E. Trends in Diabetes Treatment and Control in U.S. Adults, 1999–2018. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2219–28. 10.1056/NEJMsa2032271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Nathan DM, Lachin JM, Bebu I, Burch HB, Buse JB, et al. Glycemia Reduction in Type 2 Diabetes - Microvascular and Cardiovascular Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(12):1075-88. 10.1056/NEJMoa2200436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Zeller M, Danchin N, Simon D, Vahanian A, Lorgis L, Cottin Y, et al. Impact of Type of Preadmission Sulfonylureas on Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Diabetic Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4993-5002. 10.1210/jc.2010-0449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Holstein A, Plaschke A, Egberts EH. Lower Incidence of Severe Hypoglycaemia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Treated with Glimepiride Versus Glibenclamide. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17(6):467-73. 10.1002/dmrr.235. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Glyburide drug use statistics https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Glyburide. Accessed on 09/20/2022.