Abstract

Corynebacterium species are globally ubiquitous in human nasal microbiota across the lifespan. Moreover, nasal microbiota profiles typified by higher relative abundances of Corynebacterium are often positively associated with health. Among the most common human nasal Corynebacterium species are C. propinquum, C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens, and C. tuberculostearicum. Based on the prevalence of these species, at least two likely coexist in the nasal microbiota of 82% of adults. To gain insight into the functions of these four species, we identified genomic, phylogenomic, and pangenomic properties and estimated the functional protein repertoire and metabolic capabilities of 87 distinct human nasal Corynebacterium strain genomes: 31 from Botswana and 56 from the U.S. C. pseudodiphtheriticum had geographically distinct clades consistent with localized strain circulation, whereas some strains from the other species had wide geographic distribution across Africa and North America. All four species had similar genomic and pangenomic structures. Gene clusters assigned to all COG metabolic categories were overrepresented in the persistent (core) compared to the accessory genome of each species indicating limited strain-level variability in metabolic capacity. Moreover, core metabolic capabilities were highly conserved among the four species indicating limited species-level metabolic variation. Strikingly, strains in the U.S. clade of C. pseudodiphtheriticum lacked genes for assimilatory sulfate reduction present in the Botswanan clade and in the other studied species, indicating a recent, geographically related loss of assimilatory sulfate reduction. Overall, the minimal species and strain variability in metabolic capacity implies coexisting strains might have limited ability to occupy distinct metabolic niches.

Keywords: nasal microbiota, phylogenetics, pangenomics, metabolism, Corynebacterium accolens, Corynebacterium propinquum, Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum, Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum, Corynebacterium

INTRODUCTION

Nasal Corynebacterium species are frequently associated with health in compositional studies of human nasal microbiota. Corynebacterium are gram-positive bacteria in the phylum Actinobacteria (Actinomycetota). Based on studies from five continents, Corynebacterium species begin colonizing the human nasal passages before two months of age (1–13). Corynebacterium colonize both the skin-coated surface of the nasal vestibule (aka nostrils/nares) and the mucus-producing nasal respiratory epithelium coating the nasal passages posterior of the limen nasi through the nasopharynx (14–19). The bacterial microbiota of the human nasal passages from the nostrils through the nasopharynx is highly similar, and we refer to it herein as the human nasal microbiota.

Pediatric nasal microbiota profiles characterized by a high relative abundance of Corynebacterium (sometimes paired with a high relative abundance of Dolosigranulum) are often associated with health rather than a specific disease or disease-risk state in children (1, 2, 4, 7, 11–13, 20–30). In young children, the genus Corynebacterium (alone or with Dolosigranulum) is negatively associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae nasal colonization, which is important because pneumococcal colonization is a necessary precursor to invasive pneumococcal disease (13, 20, 22, 25, 28). For example, in young children in Botswana, the genus Corynebacterium is negatively associated with S. pneumoniae colonization both in a cross-sectional study of children younger than two years (25) and in a longitudinal study of infants followed from birth to one year (13). In contrast to these genus-level associations, little is known about species-level prevalence and relative abundance of nasal Corynebacterium in children. However, in a cultivation-based study, C. pseudodiphtheriticum is positively associated with ear and nasal health in young Indigenous Australian children (age 2–7 years), as was D. pigrum (29).

In adult nasal microbiota, the prevalence of Corynebacterium is as high as 98.6% based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Table S4A in (31)). Like children, some adults have nasal microbiota profiles characterized by a high relative abundance of Corynebacterium (18, 32). At least 23 validly published species of Corynebacterium can be cultivated from the adult nasal passages (17, 33). However, among these, C. accolens and C. tuberculostearicum (and/or other members of the C. tuberculostearicum species complex (34)) followed by C. propinquum and C. pseudodiphtheriticum are the most common in human nasal microbiota, in terms of both relative abundance and prevalence (15, 17, 31, 33). Indeed, the human nasal passages appear to be a primary habitat for C. accolens, C. propinquum and C. pseudodiphtheriticum, whereas C. tuberculostearicum is also common, often at high relative abundances, on other human skin sites (31, 34–36)].

Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization increases the risk of invasive infection at distant body sites, and the infection isolate matches the colonizing isolate in ~80% of cases (37–40). In the absence of an effective vaccine, there is growing interest in identifying nasal microbionts that confer colonization resistance to S. aureus. Some studies of adult nasal microbiota report a negative association between S. aureus and either the genus Corynebacterium or specific species of Corynebacterium (14, 31, 32, 41–45), whereas others do not, which might reflect strain-level variation or differences in populations studied. In addition to studies in healthy adults, many studies on the nasal microbiota of adults focus on chronic rhinosinusitis and data on the relationship between Corynebacterium and chronic rhinosinusitis continues to evolve as larger cohorts are sampled (46).

Several small human studies support the potential use of Corynebacterium species to inhibit or eradicate pathobiont colonization of the human nasal passages. For example, repeated nasal application of Corynebacterium sp. Co304 eliminated S. aureus nasal colonization in 71% of 17 adults (41). Similarly, daily use of a nasal spray of C. pseudodiphtheriticum 090104 eliminated nasal S. aureus colonization in three of four adults (47). Studies in mouse models further support potential benefits of nasal Corynebacterium. Nasal priming of infant mice with C. pseudodiphtheriticum 090104 decreases severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection and prevents secondary pneumococcal infection (48). Similarly, short-term respiratory tract colonization of mice with C. accolens reduces lung inflammation and the number of S. pneumoniae in both the upper and lower respiratory tract after a challenge (49).

Inhibition of S. pneumoniae or S. aureus in vitro by nasal Corynebacterium species displays strain-level variation, highlighting the importance of sequencing the genomes of multiple strains per species. For example, in vitro antipneumococcal activity varies between strains of nasal Corynebacterium isolates (13, 28). Also, C. accolens displays strain-level (and/or assay-based) variation with respect to inhibition (50) versus enhancement (14) of S. aureus growth in vitro. Some of these inhibitory interactions are characterized, including identification of the mechanism. C. accolens strains secrete the triacylglycerol lipase LipS1 to hydrolyze host-surface triacylglycerols releasing nutritionally required free fatty acids that also inhibit S. pneumoniae in vitro (22, 49). In contrast to this single-species inhibition, C. pseudodiphtheriticum KPL1989 only inhibits S. pneumoniae in vitro in cocultivation with D. pigrum, via an unknown mechanism (51). Whereas C. pseudodiphtheriticum strains (in the absence of D. pigrum) display contact-independent killing of S. aureus that requires S. aureus production of phenol-soluble modulins, and resistant S. aureus mutants are less virulent (52). There are also non-inhibitory interactions with S. aureus. Under in vitro conditions where both species grow, both human nasal- and skin-associated Corynebacterium species excrete an as-yet-unidentified compound that inhibits S. aureus agr-quorum-sensing autoinducing peptides, shifting S. aureus towards a colonization state (53).

Nasal Corynebacterium also interact with other common commensal/mutualistic nasal microbionts. For example, C. accolens, C. pseudodiphtheriticum, and C. propinquum enhance the growth yield of D. pigrum in vitro (51); this might be due to a positive metabolic interaction, such as cross-feeding. C. propinquum encodes a biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) for the siderophore dehydroxynocardamine that is transcribed in vivo in human nasal passages, and dehydroxynocardamine iron sequestration inhibits the growth of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species in vitro (54).

Overall, their ubiquity, frequent positive associations with health, and potential therapeutic use raise fundamental questions about the role of Corynebacterium species in human nasal microbiota. To increase genomic and metabolic knowledge of these, we performed systematic phylogenomic and pangenomic analyses of four common human nasal-associated Corynebacterium species. To increase the generalizability of our findings, we analyzed genomes of 87 nasal strains collected across two continents and from a broad age range of children and adults. Nasal strains of C. pseudodiphtheriticum overwhelmingly partitioned into clades by country of origin, consistent with geographically restricted strain circulation. Comparison of the core versus accessory genome of each of these four Corynebacterium species demonstrated that all COG categories associated with metabolism were enriched in the core genome, indicating limited strain-level metabolic variation within each species. Furthermore, a qualitative analysis of KEGG modules revealed that these four species share the majority of KEGG modules with few species, or even clade, specific metabolic abilities. However, we did find that the clade of C. pseudodiphtheriticum dominated by strains from the U.S. lacked the module for assimilatory sulfate reduction, which is key for biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids. To provide broader context, we compare the predicted metabolic abilities of nasal Corynebacterium species to two well-studied Corynebacterium species, C. diphtheriae and C. glutamicum, and to common nasal species from other bacterial genera.

RESULTS

Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum displays geographically restricted strain circulation.

To compare the genomic content and phylogenomic relationships among and within four Corynebacterium species commonly found in human nasal microbiota, we isolated strains from the nasal vestibule (nostrils) of generally healthy children and adults in the U.S. and from nasopharyngeal swabs of mother-infant pairs in Botswana. After whole-genome sequencing of selected isolates using Illumina sequencing (Table S1), we compared our 87 distinct nasal strain genomes to publicly available genomes of the type strain plus several other reference strains of each species, for a total of 20 reference genomes (54–59).

We confidently assigned each new nasal isolate to a species in two steps. First, we generated a maximum-likelihood phylogenomic tree based on 632 shared single-copy core gene clusters (GCs) from 107 strain genomes (Fig. S1A) and identified which were in a clade with the type strain of each species (Fig. S1B; type strains in bold). C. macginleyi is the closest relative of C. accolens and these two species are challenging to distinguish by partial 16S rRNA gene sequences. Inclusion of three C. macginleyi genomes in this phylogenomic analysis afforded confident assignment of candidate C. accolens strains to a species. This overall phylogenomic tree (Fig. S1B) confirmed that C. propinquum and C. pseudodiphtheriticum are more closely related to each other whereas C. macginleyi, C. accolens, and C. tuberculostearicum are more closely related to each other, with C. macginleyi closest to, yet distinct from C. accolens. Second, we confirmed each strain had a pairwise average nucleotide identity (ANI) of ≥ 95% for core GCs compared to the type strain of its assigned species (Fig. S2A). For each species, the pairwise ANIs for core GCs were very similar to those for all shared CoDing Sequences (CDS) (Fig. S2B).

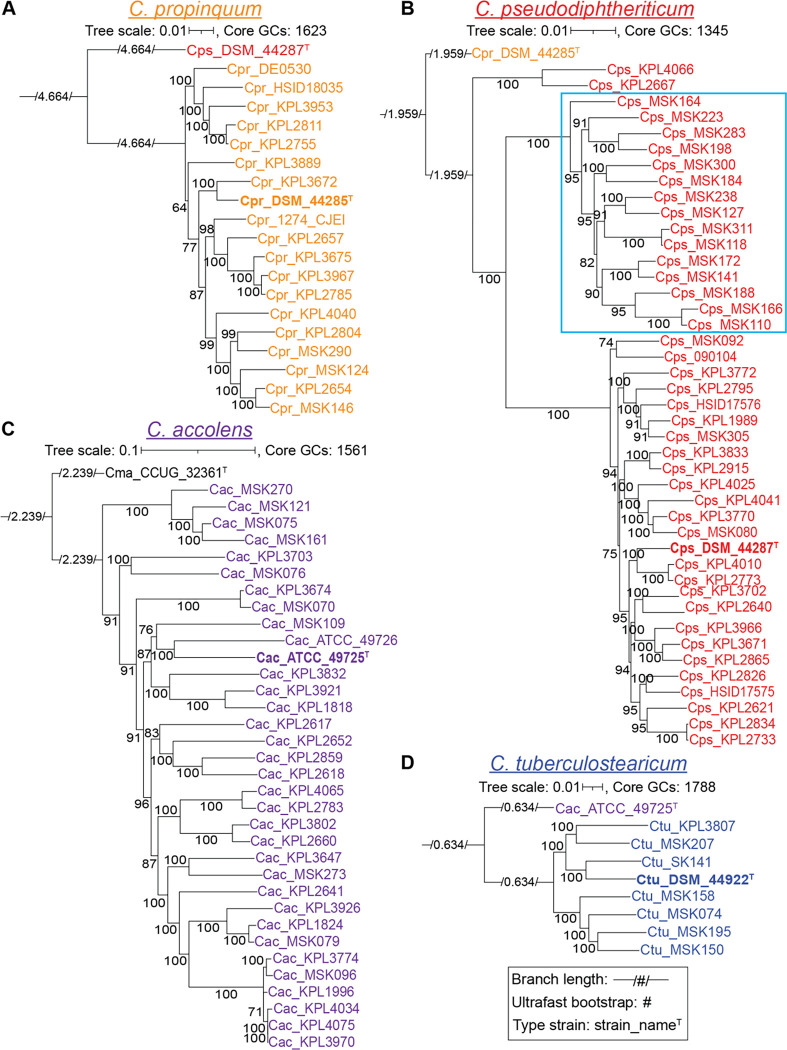

To assess the evolutionary relationships between nasal isolates from both the U.S. and Botswana, we produced individual maximum-likelihood phylogenomic trees for each species (Fig. 1) based on its conservative core genome defined by the consensus of the three algorithms cluster of orthologs triangles (COGS) (60), Markov Cluster Algorithm OrthoMCL (OMCL) (61), and bidirectional best-hits (BDBH) (Fig. S2C). These species-specific phylogenies provided a refined view of the relationships between strains based on the larger number of shared single-copy core GCs within each species (ranging from 1345 to 1788). To better approximate the root of each species-specific tree (Fig. 1), we used the type strain of the most closely related species in the multispecies phylogenomic tree (Fig. S1) as the outgroup (Fig. S2D). With a relatively even representation of Botswanan and U.S. strains (40% vs. 58%), the phylogenomic tree for C. pseudodiphtheriticum had two large, well supported clades dominated respectively by nasal strains from Botswana (15/15) or from the U.S. (20/22), indicating a restricted distribution of strains by country (Fig. 1B). Of MSK-named strains, 86% were collected in Botswana and 14% in the U.S., whereas all KPL-named strains were collected in the U.S. We avoided calculating geographic proportions within major clades for C. propinquum (Fig. 1A) and C. accolens (Fig. 1C) because of the disproportionately high representation of U.S. strains (80%) and for C. tuberculostearicum (Fig. 1D) because there were only 6 nasal strains with 5 from Botswana. Within these limitations, the phylogenomic analysis of these three species revealed some remarkably similar strains present in samples collected in the U.S. and Botswana based on their residing together in terminal clades. This raises the possibility of wide geographic distribution of a subset of similar strains for each of these three species across Africa and North America.

Figure 1. Species-specific phylogenomic trees show a geographic pattern of clades for C. pseudodiphtheriticum.

Each panel shows a core-genome-based maximum likelihood species-specific phylogeny. The majority (86%) of the MSK-named strains are from Botswana, whereas all KPL-named strains are from the U.S. (A) Phylogeny of 19 C. propinquum strains based on 1,623 core GCs shows two major clades (BIC value 9762417.2123). (B) Phylogeny of 43 C. pseudodiphtheriticum strains based on 1,345 core GCs shows three major clades, one of which is entirely composed of MSK strains from Botswana (15/15, outlined in light blue), whereas the other two have a majority of U.S. nasal strains (KPL), with 2/2 and 20/22, respectively (BIC value 10177769.6675). The branching pattern separating the Botswanan and U.S. clades was well supported with ultrafast bootstrap values ≥ 95% (61). (C) Phylogeny of 34 C. accolens strains based on 1,561 core GCs with the majority collected in the U.S. shows most MSK strains dispersed throughout (BIC value 10700765.2332). (D) Phylogeny of eight C. tuberculostearicum strains based on 1,788 core GCs with 6 nasal isolates from Botswana and the U.S. (BIC value 10452720.3067). For each species-specific phylogeny, we chose the type strain from the most closely related species (Fig. S1B) as the outgroup. Each phylogeny was made from all shared conservative core GCs for a given species (Fig. S2C), including the subset of GCs that were absent in the corresponding outgroup (Fig. S2D) to keep the phylogenies at the highest resolution possible for each species. These species level phylogenies were created to increase the resolution between Corynebacterium strain genomes from Figure S1, which is based on only the 632 GCs shared by all strains. The increase in shared GCs for species specific trees ranged from 601–936 GCs. Each phylogeny was generated with IQ-Tree v2.1.3 using model finder, edge-linked-proportional partition model, and 1,000 ultrafast rapid bootstraps. A large majority of the branches have highly supported ultrafast bootstrap values with the lowest at 64 on an ancestral branch in the C. propinquum phylogeny. Type strains are indicated with a superscript T. Ancestral branch lengths are indicated numerically within a visually short branch to fit on the page.

The sizes of the core genomes of four common nasal Corynebacterium species have leveled off.

Based on rarefaction analysis, the core genomes of C. propinquum, C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens, and C. tuberculostearicum have reached a stable size and are unlikely to decrease much further with the sequencing of additional strains (Fig. 2 Ai–Aiv). Based on the respective Tettelin curves (red line), the C. tuberculostearicum core genome stabilized first at ~7 genomes; however, with the fewest genomes at 8 this might be an upper bound that will continue to decrease with additional strain genomes. In comparison, C. pseudodiphtheriticum had the largest number of strain genomes at 43, with pairwise ANIs of ≥ 96.2% (Fig. S2Aii), and its core genome stabilized last at ~37 genomes.

Figure 2. C. propinquum, C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens, and C. tuberculostearicum have core genomes that have leveled off and pangenomes that remain open.

(A) All four Corynebacterium species have a core genome that has leveled off using a Tettelin curve fit model. (Ai) The C. propinquum core genome (n = 19) leveled off at ~12 genomes. (Aii) The C. pseudodiphtheriticum core genome (n = 42) leveled off at ~19 genomes. (Aiii) The C. accolens core genome (n = 33) leveled off at ~ 21 genomes. (Aiv) The C. tuberculostearicum core genome (n = 8) leveled off at ~7 genomes. Two best fit curve line models are shown for the core genome: Tettelin (red) and Willenbrock (blue). (B) The pangenomes for the four Corynebacterium species (i-vi) remain open as indicated by the continuous steep slope of the best fit line shown in purple. Core and pangenome size estimations were calculated from 10 random genome samplings (represented by gray dots) using the OMCL algorithm predicted GCs with GET_HOMOLOGUES v24082022.

The proportion of an individual genome of each of these nasal Corynebacterium species devoted to conservative core GCs ranged from 72% for C. pseudodiphtheriticum (1517/2105) to 79% for C. tuberculostearicum (1788/2250). This is based on the average number of CDS per genome (Table 1). (We estimated CDS using Prokka:Prodigal (62) and then estimated the percentage of each genome occupied by conservative core GCs using GET_HOMOLOGUES (63).) The average / median genome size for each species ranged from ~2.33 / 2.33 Mb for C. pseudodiphtheriticum to ~2.51 / 2.52 Mb for C. propinquum with the average / median predicted CDS per genome ranging from 2105 / 2096 for C. pseudodiphtheriticum to 2265 / 2272 for C. propinquum (Table 1). These sizes and proportions are consistent with the reduced genome size and the GCs per genome of host-associated compared to environment-associated Corynebacterium species (64). For comparison, average and/or median reported genomes sizes for common human nasal microbionts from other genera are as follows: Cutibacterium acnes 2.51 Mb (65), Staphylococcus epidermidis 2.5 Mb (66), Lawsonella clevelandensis 1.79 Mb (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=Lawsonella+clevelandensis on 05/03/23), Haemophilus influenzae 1.84 Mb (67), D. pigrum 1.93 / 1.91 Mb (68), and Staphylococcus aureus 2.83 Mb (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=Staphylococcus%20aureus%5BOrganism%5D&cmd=DetailsSearch on 05/03/23).

Table 1.

Basic genomic information for four common human nasal-associated Corynebacterium species.

| Corynebacter ium species | # Strain Genomes (# Nasal isolates) | Average (median) genome size (Mb) | Average (median) CDS/genome | Average (median) G+C% | Conservative Core GCs/speciesa | Pangenome GCs/speciesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. propinquum | 19 (15) | 2.51 (2.52) | 2265 (2272) | 56.47 (56.48) | 1623 | 3777 |

| C. pseudodiphthe riticum | 43 (39) | 2.33 (2.33) | 2105 (2096) | 55.29 (55.29) | 1345 | 4590c |

| C. accolens | 34 (32) | 2.50 (2.49) | 2304 (2294) | 59.46 (59.44) | 1561 | 4220d |

| C. tuberculosteari cum | 8 (6) | 2.39 (2.39) | 2250 (2253) | 59.86 (59.88) | 1788 | 3232 |

GET_HOMOLOGUES conservative core GCs predicted from the consensus of BDBH, OMCL, and COGS algorithms.

GET_HOMOLOGUES pangenome GCs predicted from the consensus of OMCL, and COGS algorithms.

Cps_090104 removed from dataset for this analysis due to false % core lower bound.

Cac_ATCC_49756 removed from dataset for this analysis due to false % core lower bound.

The pangenomes of these four human nasal-associated Corynebacterium species remain open.

With the number of strain genomes analyzed (Table 1), the pangenome of each of the four species continued to increase with each additional new genome, indicating that all are open (Fig. 2 Bi–Biv). Parameters used to generate a pangenome via rarefaction yielded an overly conservative estimate of its size in GCs. Therefore, we used two other approaches to estimate the number of GCs in the pangenome for each species. These pangenome composition estimates are a lower bound for each species and will increase with sequencing of additional strain genomes. Starting with GET_HOMOLOGUES, we estimated pangenome size using the COG triangle and OMCL clustering algorithms. The pangenome size and its proportion contributed by core versus accessory GCs for each species ranged from 3232 GCs with 56% core and 44% accessory for C. tuberculostearicum to 4590 GCs with 33% core and 67% accessory for C. pseudodiphtheriticum (Table 2; Fig. S3A). The 56% core percentage for C. tuberculostearicum is likely an overestimate since this pangenome is based on only 8 genomes. This range of 33% to 56% for core genes per pangenome is similar to estimates for other human upper respiratory tract microbionts, such as D. pigrum (31%) (68), Staphylococcus aureus (36%), and Streptococcus pyogenes (37%) (69).

Table 2.

Pangenomic estimation of human nasal-associated Corynebacterium species based on three different platforms.

| Platform Species | Pangenome size (GCs) | % Core GCs/pangenome | % Accessory GCs/pangenome |

|---|---|---|---|

| GET HOMOLOGUES a | |||

| C. propinquum | 3777 | 43% | 57% |

| C. pseudodiphtheriticum c | 4590 | 33% | 67% |

| C. accolens d | 4220 | 40% | 60% |

| C. tuberculostearicum | 3232 | 56% | 44% |

| anvi’o | |||

| C. propinquum | 3108 | 59% | 40% |

| C. pseudodiphtheriticum | 3590 | 48% | 51% |

| C. accolens | 3427 | 57% | 42% |

| C. tuberculostearicum | 2907 | 66% | 32% |

| PPanGGOLiN | % Persistent | ||

| C. propinquum | b | 63% | 37% |

| C. pseudodiphtheriticum | b | 49% | 51% |

| C. accolens | b | 59% | 41% |

| C. tuberculostearicum | b | 69% | 31% |

GET_HOMOLOGUES pangenome size, % core, and % accessory are from the consensus of OMCL and COGS algorithms.

Pangenome size was estimated in anvi’o then the GCs imported into PPanGGOLiN to estimate persistent vs. accessory genome percentages.

Cps_090104 was removed from dataset only for this analysis due to an aberrant % core lower bound.

Cac_ATCC_49756 was removed from dataset only for this analysis due to an aberrant % core lower bound.

Next, we used anvi’o version 7.1.2 to estimate the core- and pangenomes (70). The number of GCs in the core genome of each species estimated with GET_HOMOLOGUES was within 6–23% of those estimated with anvi’o; however, the GET_HOMOLOGUES estimated pangenome sizes were 11–32% larger (Fig. S3A, File S1). Consistent with this, the estimated single-copy core as a proportion of the pangenome using anvi’o was higher for each species ranging from 41% to 64% (Fig. S3B).

We also used anvi’o to visualize the strain-level variation in gene presence and absence within the four human nasal-associated Corynebacterium species (Fig. S3B). Manually arraying the genomes in anvi’o to correspond with their species-specific phylogenomic tree (Fig. 1) showed that some blocks of gene presence/absence correlated with the core-genome-based phylogenetic relationships among strains, but others did not (Fig. S3B). This is consistent with gene gain and loss playing a role in strain diversification with some of this due to mobile genetic elements and horizontal gene transfer (71, 72).

Gene clusters assigned to the COG categories associated with metabolism are highly enriched in the core genomes of common nasal Corynebacterium species.

To predict and compare functions based on the pangenomes of each species, we assigned GCs to COG categories and used PPanGGOLiN to define the persistent versus the accessory genome (Table S2) (73). (Note that the PPanGGOLiN definition of persistent genome differs slightly from the GET_HOMOLOGUES definition of core genome.) As is common in bacteria, only about 65% of the GCs in the persistent genome and 26–36% of the GCs in the accessory genome of each species had an informative assignment to a definitive COG category (Figs. 3Ai–iv & S4Ai-iv). There was also variability in the size of the accessory genome among strains within each species (Fig. S4A, S4B). We next generated functional enrichment plots for COG categories in the persistent versus the accessory genome of each species (Fig. 3Bi–vi). GCs assigned to “mobile genetic elements” (MGEs; orange bar Fig. 3B) were overrepresented in the accessory genome of each species with the ratio of GCs in the accessory/persistent genome ranging from 4.2 (C. tuberculostearicum) to 36.1 (C. pseudodiphtheriticum). GCs assigned to “defense systems” (purple bar Fig. 3B), which protect bacteria from MGEs, were more evenly distributed with the ratio of GCs in the accessory/persistent genome ranging from 1 (C. tuberculostearicum) to 2.9 (C. pseudodiphtheriticum). These findings are consistent with pangenomic analyses of other bacterial species, including our prior analysis of the candidate beneficial nasal bacterium D. pigrum (68). Our COG-enrichment analysis also showed that all the COG categories associated with metabolism, from “energy production and conversion” (pale orange) through “secondary metabolites” (pink) in Fig. 3B, were highly overrepresented in the persistent (or core) genome of each species with ratios of accessory/persistent ranging from 0.02 to 0.56 (median of 0.16). The exception was an accessory/persistent GC ratio of 1.2 for “secondary metabolites” in C. pseudodiphtheriticum. The overrepresentation of metabolism in the persistent genome of each species points to limited strain-level variation in metabolic capabilities, such as “carbohydrate or amino acid metabolism”. This contrasts with our previous analysis of D. pigrum in which GCs assigned to the COG category “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” are enriched in the accessory genome (ratio 1.66) (68).

Figure 3. GCs assigned to COG metabolism categories are overrepresented in the persistent compared to the accessory genomes of each species indicating limited strain-specific metabolism.

We identified the COG functional annotations for GCs using anvi’o and then used PPanGGOLiN to assign GCs to the persistent vs. accessory genome. (A) Over one-third of the GCs in each species (i-iv) were assigned as uninformative (black), ambiguous (dark gray), or unclassified (gray) across both the persistent and accessory genome. The combined percentage of each of these categories out of all the genes per species was 38.1% Cpr, 37.9% Cps, 37.1% Cac, and 38.3% Ctu. For each species, the percentage of GCs with an informative COG assignment was higher in the persistent genome, 64.9% Cpr (1262), 65.3% Cps (1156), 64.7% Cac (1300), and 63.5% Ctu (1264), than in the accessory genome, with 28.9% Cpr (336), 29.9% Cps (543), 25.7% Cac (363), and 35.6% Ctu (326). (B) Functional enrichment of GCs in the persistent vs. the accessory genome for the different COG categories. Metabolic COG categories, e.g., those involved in energy production (pale orange), or in amino acid (yellow), nucleotide (gold), carbohydrate (khaki), and lipid metabolism (dark salmon), were enriched in the persistent genome of each species. In contrast, mobilome (bright orange) and to a lesser extent defense mechanisms were enriched in the accessory genomes. Each Corynebacterium species shared similar COG functional enrichment ratios of GCs in its persistent vs. its accessory genome.

Common human nasal-associated Corynebacterium species have a largely shared metabolic capacity.

In adult nasal microbiota, based on 16S rRNA V1-V3 sequences, the prevalence of the genus Corynebacterium is as high as 98.6%, with highly prevalent species including C. accolens (prevalence of 82%), C. tuberculostearicum (93%), C. propinquum (18%), and C. pseudodiphtheriticum (20%). In these data, 82% of the adult nostril samples contained ≥ 2 of these 4 Corynebacterium species, 30% contained ≥ 3, and 2.4% contained all 4 species (Tables S4A-B and S7 in (31). Thus, there is a high probability of coexistence of these Corynebacterium species in nasal microbial communities. This finding, combined with the enrichment of GCs assigned to metabolism COG categories in each persistent genome, led us to hypothesize that there would be much species-specific variation in core metabolic capabilities enabling the different nasal Corynebacterium species to occupy distinct metabolic niches within human nasal microbiota. To focus only on these 4 human nasal-associated species, we excluded the 3 C. macginleyi reference genomes and used the remaining 104 genomes for all subsequent analyses. To test our hypothesis, we assessed variation in metabolic capacity among the four species using anvi’o v7.1.2 to estimate the metabolic capabilities described by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) metabolic annotations. This yielded KEGG Orthology family (KOfam) annotations for GCs as well as module completion results for each KEGG module that had at least one KOfam present (Table S3A). We examined the number of complete KEGG pathway modules, defined as “functional units of gene sets in metabolic pathways, including molecular complexes” per https://www.genome.jp/kegg/module.html. In contrast to our hypothesis, we learned that C. propinquum, C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens, and C. tuberculostearicum encode highly conserved core metabolic capabilities sharing 50 of 66 (76%) detected complete KEGG modules, with completeness defined as detection of ≥ 0.75 of the genes in a module (Fig. 4A). Various combinations of three of the four species shared an additional seven modules (11%). There were a few differences between the C. propinquum-C. pseudodiphtheriticum clade and the C. accolens-C. tuberculostearicum clade (Fig. S1B), with three and five clade-specific KEGG modules, respectively. Only C. tuberculostearicum, which is broadly distributed across human skin sites as well as in the nasal passages (31, 34–36) was predicted to encode two complete KEGG modules that were absent in the other three nasal species; these are discussed below.

Figure 4. These four common human-nasal-associated Corynebacterium species have a largely shared metabolic capacity.

All genomes were analyzed using KEGG annotations of genes in each anvi’o contigs database with KEGG Orthology (KO) numbers from the KEGG KOfam database. Completion scores were calculated for each module in each genome ranging from 0–1 representing the fraction of enzymes present out of total enzymes that make up each module. To identify the complete KEGG modules shared by the four common nasal Corynebacterium species, we ran a module enrichment analysis in which we assigned each genome a species group and compared whether that complete module was more likely to be found in one group or multiple groups. Modules with an adjusted p-value <0.05 were considered enriched in their associated species and modules that were not significantly enriched (adjusted p-value >0.05) in comparisons in three out of the four species, were categorized as shared. (A) Venn diagram summarizing complete (completion score ≥ 0.75) KEGG modules shared between the four Corynebacterium species: C. propinquum (Cpr), C. pseudodiphtheriticum (Cps), C. accolens (Cac), and C. tuberculostearicum (Ctu). Specific modules are grouped by the subgroup of ≤ 3 species encoding these and shown in boxes surrounding the Venn diagram with species labels. (B) Detailed list of the functions encompassed by the 50 KEGG modules shared by all four Corynebacterium species grouped by module category. In amino acid metabolism, gray indicates amino acids lacking complete biosynthesis modules; orange indicates that biosynthetic capabilities that vary by species (as influenced by predicted assimilatory sulfate reduction capabilities); deep pink indicates a predicted requirement for an exogenous source of either Asp or Asn; and light pink indicates the ability to make Met depends on either exogenous Asp or Asn. (C) Manual assessment for Corynebacterium orthologs predicted full biosynthetic pathway in several instances where KEGG annotations gave completion scores < 1. We performed blastX with enzymes with names in bold. (Ci) glycogen degradation and synthesis. (Cii) synthesis of UDP-glucose. (Ciii) Assimilatory sulfate reduction. Noted on the right side is the pathway defined in the KEGG module and on the left is the pathway identified in C. glutamicum by Ruckert, Kalinowski, and colleagues (97).

Nasal Corynebacterium species encode for central carbohydrate metabolism.

To contextualize our findings within the genus Corynebacterium, we manually compared our results using genome annotation data from the KEGG database (not using anvi’o) to the genomes of the type strains of two well-studied Corynebacterium species: C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (C. glutamicumT) (74) and C. diphtheriae NCTC11397 (C. diphtheriaeT). The soil bacterium, C. glutamicum, is used to produce amino acids and its metabolism is the best studied of Corynebacterium species (75). In contrast, C. diphtheriae colonizes the human pharynx and is extensively studied because toxigenic strains cause the human disease diphtheria (76). Along with C. diphtheriaeT and C. glutamicumT, the four common human nasal Corynebacterium species all encoded complete modules for glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Fig. 4B). C. propinquum and C. pseudodiphtheriticum, along with C. glutamicumT (which grows with acetate as a sole carbon source), also possessed a complete module for the glyoxylate cycle (M00012), a shortcut of the TCA cycle that allows microbes to utilize two-carbon compounds, such as acetate, as sources of carbon (77). This module is also present in skin-associated Corynebacterium species (78). Although the glyoxylate cycle might afford C. propinquum and C. pseudodiphtheriticum a distinct metabolic niche, two-carbon compounds are not detected in previous studies of the metabolites present in human nasal secretions (79, 80). Lastly, all four species encoded a complete module for UDP-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine biosynthesis (M00909), a precursor of cell wall peptidoglycan (81). Of note, we found 61 hits across 28 D. pigrum genomes and no hits in the Corynebacterium genomes for a sialidase (K01186), which can release sialic acid from sialylated glycans found in mucus providing bacteria with carbon and nitrogen (82).

Nasal Corynebacterium species encode for synthesis of key biosynthetic cofactors and electron transport chain components.

The strain genomes of all four species contained complete modules for biosynthesis of cofactors required for synthesis of essential biomolecules and central metabolism (Fig. 4B; Table 3). These include tetrahydrofolate (M00126), a coenzyme for synthesis of amino acids and nucleic acids; coenzyme A (M00120), required for the TCA cycle; and lipoic acid (M00881), an organosulfur cofactor required in central metabolism (83). Consistent with an intact TCA cycle, all four also had complete modules for the biosynthesis of key compounds involved in the electron transport chain, including menaquinone (M00116; this was incomplete in 3 strains: C. accolens ATCC49726, C. propinquum KPL3675, C. pseudodiphtheriticum 090104), heme/siroheme (M00121, M00868, M00926 / M00846), and riboflavin (M00125). We also detected the modules for coenzyme A, lipoic acid, and heme in both C. glutamicumT and C. diphtheriaeT. Of the remaining modules detected in the nasal Corynebacterium species, more modules were shared with the human-associated bacterium C. diphtheriaeT (menaquinone, riboflavin, siroheme, molybdenum cofactor) than with the soil bacterium C. glutamicumT (tetrahydrofolate). Of note, modules for the biosynthesis of cobalamin/Vitamin B12 (M00925, M00924, M00122) were incomplete or absent in all four nasal Corynebacterium species whereas both C. glutamicumT and C. diphtheriaeT encoded a cobalamin biosynthesis module (M00122). Cobalamin is a cofactor for ribonucleotide reductases (K00525, K00526) (84), which we detected in all 104 Corynebacterium genomes.

Table 3.

D. pigrum shares a subset (green) of the predicted 50 complete KEGG modules present in the genomes of all four Corynebacterium species.

| KEGG module | KEGG Module Name | KEGG Module SubCategory |

|---|---|---|

| M00015 | Proline biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00016 | Lysine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00017 | Methionine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00018 | Threonine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00019 | Valine/isoleucine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00021 | Cysteine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00022 | Shikimate pathway | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00023 | Tryptophan biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00026 | Histidine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00045 | Histidine degradation into glutamate | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00432 | Leucine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00526 | Lysine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00527 | Lysine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00570 | Isoleucine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00844 | Arginine biosynthesis | Amino acid metabolism |

| M00149 | Succinate dehydrogenase, prokaryotes | ATP synthesis |

| M00151 | Cytochrome bc1 complex respiratory unit | ATP synthesis |

| M00155 | Cytochrome c oxidase, prokaryotes | ATP synthesis |

| M00157 | F-type ATPase, prokaryotes and chloroplasts | ATP synthesis |

| M00632 | Galactose degradation, Leloir pathway | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00909 | UDP-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine biosynthesis | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00167 | Reductive pentose phosphate cycle | Carbon fixation |

| M00009 | Citrate cycle (TCA cycle Krebs cycle) | Central carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00011 | Citrate cycle second carbon oxidation | Central carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00001 | Glycolysis (Embden-Meyerhof pathway) | Glycolysis |

| M00002 | Glycolysis | Glycolysis |

| M00003 | Gluconeogenesis | Glycolysis |

| M00086 | beta-Oxidation, acyl-CoA synthesis | Lipid metabolism |

| M00116 | Menaquinone biosynthesis | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00120 | Coenzyme A biosynthesis | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00121 | Heme biosynthesis plants and bacteria | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00125 | Riboflavin biosynthesis plants and bacteria | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00126 | Tetrahydrofolate biosynthesis | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00846 | Siroheme biosynthesis | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00868 | Heme biosynthesis | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00880 | Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00881 | Lipoic acid biosynthesis plants and bacteria | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00926 | Heme biosynthesis bacteria | Metabolism of cofactors & vitamins |

| M00140 | C1-unit interconversion, prokaryotes | Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins |

| M00048 | Inosine monophosphate biosynthesis | Nucleotide metabolism |

| M00049 | Adenine ribonucleotide biosynthesis | Nucleotide metabolism |

| M00050 | Guanine ribonucleotide biosynthesis | Nucleotide metabolism |

| M00051 | Uridine monophosphate biosynthesis | Nucleotide metabolism |

| M00053 | Pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis | Nucleotide metabolism |

| M00554 | Nucleotide sugar biosynthesis (galactose) | Nucleotide metabolism |

| M00004 | Pentose phosphate pathway | Pentose phosphate pathway |

| M00005 | PRPP biosynthesis | Pentose phosphate pathway |

| M00006 | Pentose phosphate pathway | Pentose phosphate pathway |

| M00007 | Pentose phosphate pathway | Pentose phosphate pathway |

| M00793 | dTDP-L-rhamnose biosynthesis | Polyketide sugar unit biosynthesis |

Nasal Corynebacterium species share necessary modules for nucleotide synthesis and energy generation.

All four of these common nasal Corynebacterium species had complete modules for synthesizing inosine monophosphate, adenine ribonucleotide, guanine ribonucleotide, uridine monophosphate, and pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide (Table 3). All four species also had four complete modules for ATP synthesis (M00149, M00151, M00155, M00157) as well as a reductive pentose phosphate module, which overlaps with reductive pentose phosphate modules mentioned earlier. Lastly, all four had complete modules for dTDP-L-rhamnose biosynthesis, a precursor to rhamnose cell wall polysaccharides. Rhamnose is part of the polysaccharide linker between peptidoglycan and arabinogalactan in members of Mycobacteriales, including Corynebacterium (81). Of the 11 KEGG modules related to nucleotide synthesis and energy generation shared by the four nasal Corynebacterium species, many are also present in other common nasal microbionts with 9/11 in Cutibacterium acnes KPA171202 (85), 9/11 in Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A (86), 6/11 in Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 (87), 5/11 in S. aureus USA300_FPR3757 (88), and 5/11 in a 27-strain D. pigrum pangenome (68), as well as 10/11 in C. diphtheriaeT and 9/11 in C. glutamicumT (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of biosynthetic nucleotide modules found in the four common human nasal Corynebacterium to representative strains of other nasal speciesa.

| KEGG modules | Sau | Cacn | Spn | Dpi | Sep | Cgl | Cdi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inosine monophosphate (M00048) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| adenine ribonucleotide (M00049) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| guanine ribonucleotide (M00050) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| uridine monophosphate (M00051) | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | + | ND |

| pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide (M00053) | + | + | + | ND | + | + | + |

| ATP synthesis (M00149 | ND | + | ND | ND | + | ND | ND |

| M00151 | ND | + | ND | ND | + | + | + |

| M00155 | ND | + | ND | ND | + | + | + |

| M00157) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| reductive pentose phosphate (M00167) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| dTDP-L-rhamnose (M00793) | ND | + | + | ND | + | + | + |

+ = Detected, ND = Not Detected.

Sau = Staphylococcus aureus USA300_FPR3757, Cacn = Cutibacterium acnes KPA171202, Spn = Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4, Dpi = D. pigrum 27-strain pangenome, Sep = Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A, Cgl = C. glutamicumT ATCC 13032, Cdi = C. diphtheriaeT ATCC 700971.

Human nasal Corynebacterium species have a broader metabolic capacity for biosynthesis of amino acids and cofactors/vitamins than Dolosigranulum pigrum.

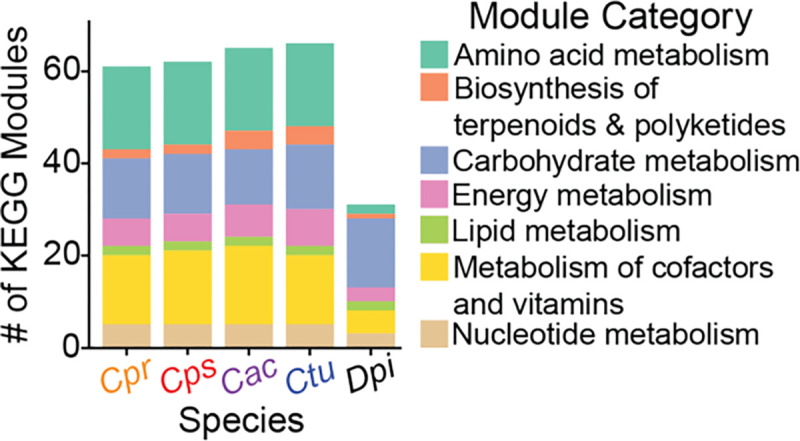

Many compositional studies of human nasal microbiota show a positive association at the genus level between Corynebacterium and Dolosigranulum, e.g., (1, 2, 4, 7, 24, 26, 51, 89). Presently, D. pigrum is the sole member of its genus. Nasal Corynebacterium species can enhance in vitro growth yields of D. pigrum, a lactic acid producing bacterium (51). Together with other prior analyses (90), these data indicate D. pigrum must access nutrients from its host and its microbial neighbors. We hypothesized that nasal Corynebacterium species with their larger genome sizes ranging from 2.3-to-2.6 Mb would have a greater number of complete KEGG modules than D. pigrum (1.9 Mb) in the pangenome for each species (Fig. 5). Using the enrichment analysis in anvi’o, we identified 30 complete modules shared by the majority (88%) of the 27 D. pigrum strain genomes (Table S3B), which is approximately half the number found in the majority of the four Corynebacterium species’ genomes (range 61–66). Only seven modules found in D. pigrum were undetectable in these four Corynebacterium species (Table 5), mostly related to carbohydrate metabolism. D. pigrum shared only about a third of the KEGG modules shared by all four Corynebacterium species (Table 3, highlighted in green). Specifically, the four Corynebacterium species shared 15 modules related to amino acid metabolism and 8 modules related to cofactor/vitamin metabolism in the majority of their genomes that were absent/incomplete in D. pigrum (Table 3; Table S3B). Overall, the four Corynebacterium species shared 50 complete KEGG modules with 15 for amino acids, 15 for carbohydrates, and 18 for cofactors and vitamins. In comparison, of the 30 complete KEGG modules identified in the majority of the D. pigrum genomes, there were 15 for carbohydrates and 4 for cofactors/vitamins. Previous genome-based estimations of D. pigrum’s metabolism predict auxotrophy for most (13/20) amino acids and synthesis of L-alanine, L-aspartate, L-asparagine, L-glutamine, glycine, L-serine, and L-tyrosine (90). In contrast, our current analysis, which includes additional strain genomes, found that 13-to-15 of these 27 genomes are predicted to synthesize 5 amino acids for which there are no KEGG modules: alanine, aspartate, asparagine, glutamine, and glycine. We did this by manually checking for KOfams encoding for enzymes that synthesize these amino acids. However, the KEGG modules for serine (M00020) (Table S3B) or tyrosine (M00025, M00040) biosynthesis were absent. D. pigrum also has predicted auxotrophies for polyamines (spermidine and putrescine); plus, many B vitamins, e.g., thiamine (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), niacin (vitamin B3), biotin (B7), and p-Aminobenzoate (PABA), a component of folate (vitamin B9) (51, 90). A potential limitation of this analysis is that, although representative members of Lactobacillales are well studied, it is possible that current annotation software is more effective for Corynebacterium species than for D. pigrum.

Figure 5. The pangenome of each of the four nasal Corynebacterium species have more amino acid and cofactor/vitamin metabolic capacity than does D. pigrum.

Distribution of KEGG modules with a completion score ≥ 0.75 by module category in the pangenomes of four common human-nasal-associated species of Corynebacterium (avg. genome size 2.3 – 2.5 Mb) and in D. pigrum (avg. genome size 1.9 Mb), a common human-nasal-associated bacterium that is often positively associated with the genus Corynebacterium in compositional studies of human nasal microbiota.

Table 5.

D. pigrum has eight complete KEGG modules that are absent from the four nasal Corynebacterium species analyzed.

| KEGG module | KEGG Module Name | KEGG Module SubCategory |

|---|---|---|

| M00159 | V/A-type ATPase, prokaryotes | ATP synthesis |

| M00008 | Entner-Doudoroff pathway, glucose-6P → glyceraldehyde-3P + pyruvate | Central carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00308 | Semi-phosphorylative Entner-Doudoroff pathway, gluconate → glycerate-3P | Central carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00082 | Fatty acid biosynthesis, initiation | Fatty acid metabolism |

| M00854 | Glycogen biosynthesis, glucose-1P → glycogen/starch | Other carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00550 | Ascorbate degradation, ascorbate → D-xylulose-5P | Other carbohydrate metabolism |

| M00061 | D-Glucuronate degradation, D-glucuronate → pyruvate + D-glyceraldehyde 3P | Other carbohydrate metabolism |

C. tuberculostearicum is predicted to degrade glycogen unlike the other three nasal-associated Corynebacterium species.

Among the four nasal-associated species analyzed, C. tuberculostearicum was predicted to have two complete (≥ 0.75) KEGG modules absent from the other three (Fig. 4A): glycogen degradation (M00855) and UDP-glucose biosynthesis (M00549). To assess whether these two modules are present in other human skin-associated Corynebacterium species (78) or in non-Corynebacterium human nasal-associated bacterial species, we examined the KEGG database information for three common skin Corynebacterium species (Corynebacterium simulans PES1 (91), Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii DSM 44395 (92), and Corynebacterium amycolatum FDAARGOS_1108 (93)), and for the following common nasal species: C. acnes KPA171202 (85), S. epidermidis RP62A (86), S. pneumoniae TIGR4 (87), S. aureus USA300_FPR3757 (88), and D. pigrum (27-strain pangenome) (68) (Table 6). The glycogen degradation module (M00855) was detected in all 27 D. pigrum strain genomes, S. epidermidis RP62A, C. acnes KPA171202, and S. pneumoniae TIGR4, suggesting it is common in nasal microbiota, and in the skin-associated species C. simulans (and in C. glutamicumT). However, C. tuberculostearicum and D. pigrum each lacked one of the four enzymes in the glycogen degradation module resulting in completion scores of 0.75. C. tuberculostearicum had the 4-alpha-glucanotransferase but lacked a glycogen debranching enzyme, whereas D. pigrum had a debranching enzyme but lacked the 4-alpha-glucanotransferase. Like C. tuberculostearicum, the KEGG database marks C. glutamicumT as missing the gene for the glycogen debranching enzyme glgX (K02438, EC:3.2.1.196). However, C. glutamicum both synthesizes and degrades glycogen when grown in media with glucose and its GlgX performs glycogen debranching in vitro (94) (Fig. 4Ci). Additionally, disruption of glgX in C. glutamicum has phenotypic effects related to glycogen usage. The functional C. glutamicum GlgX has only 46% identity to the functional E. coli GlgX (94). A blastP of the translated 836 amino acid sequence of glgX from C. glutamicumT against the non-redundant protein database returned hits in C. tuberculostearicum at 73% identity and 85% query coverage, along with hits to multiple other Corynebacterium species (Table S3C). This is consistent with published data from Seibold and Eikmanns. A custom blastx of our 104 genomes against that same amino acid sequence returned a single hit in each of the 8 C. tuberculostearicum genomes, at 72–73% identity along 86% of the length of GlgX (Table S3D). This predicts that, like C. glutamicum, C. tuberculostearicum degrades glycogen, an ability shared with other skin Corynebacterium and with some non-Corynebacterium nasal bacteria. The other 3 nasal species analyzed lacked all steps in this module, including GlgX, indicating they either use a currently unrecognized set of enzymes for glycogen degradation or lack this ability. As with cysH (discussed below), the current KEGG annotations miss the glgX gene that encodes the glycogen debranching enzyme in C. glutamicumT and C. tuberculostearicum, and likely other Corynebacterium species.

Table 6.

Presence of the two KEGG modules detected in C. tuberculostearicum but not in C. accolens, C. propinquum, or C. pseudodiphtheriticum in other skin- associated Corynebacterium species and common nasal bacterial species.

| species | Glycogen degradation (M00855) | UDP-glucose (M00549) |

|---|---|---|

| C. simulans PESI | + | + |

| C. kroppenstedtii DSM 44395 | ND | + |

| C. amycolatum FDAARGOS_1108 | ND | + |

| C. glutamicumT ATCC 13032 | + | + |

| C. diphtheriaeT NCTC11397 | + | + |

| S. aureus USA300_FPR3757 | ND | + |

| S. epidermidis RP62A | + | + |

| D. pigrum a | + | ND |

| C. acnes KPA171202 | + | + |

| S. pneumoniae TIGR4 | + | + |

+ = Detected, ND = Not Detected.

Assessed 27-strain pangenome.

We next assessed the completion of the glycogen synthesis module because capacity for both synthesis and degradation points to the use of glycogen for energy storage. The glycogen synthesis module (M00854; Fig. 4Cii) was only 2/3 complete in all 8 C. tuberculostearicum genomes, C. diphtheriaeT, and C. glutamicumT. According to KEGG, they are all missing a glycogen synthase (for which there are many orthologs listed in KEGG including glgA EC 2.4.1.21). However, C. glutamicumT is known to possess glgA (95). In contrast, this module was complete in 26/27 D. pigrum genomes, S. epidermidis RP62A, C. acnes KPA171202, and S. pneumoniae TIGR4. A custom blastx of our Corynebacterium genomes against the translated glgA amino acid sequence from C. glutamicumT gave 8 hits, one in each of the C. tuberculostearicum genomes with 73–74% identity along its full length (390 aa) (Table S3E). Thus, it is likely that C. tuberculostearicum uses glycogen synthesis and degradation for energy storage similarly to C. glutamicumT.

The UDP-glucose biosynthesis module (M00549) fully detected in C. tuberculostearicum (completion score = 1) was 2/3 complete in the other nasal Corynebacterium genomes and in the D. pigrum genomes, but present in the other species analyzed (Table 6). UDP-glucose is a key part of central metabolism. It is the activated form of glucose that serves as a precursor for other activated carbohydrates and is used by a vast majority of organisms for glucosyl transfers. Phosphoglucomutase (pgm) performs the second step in its three-step biosynthesis module (Fig. 4Ciii). C. tuberculostearicum encoded pgm, which was absent in the other nasal Corynebacterium species. In contrast, the D. pigrum genomes lacked the third step, a UDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase or a UTP--glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase. Upon blastx of the pgm amino acid sequence from C. glutamicumT against the custom Corynebacterium genomes the only 8 hits were in each of the C. tuberculostearicum genomes with 78% identity along 537–553 of 554 amino acids (Table S3F). A blastx of the translated pgm amino acid sequence from C. tuberculostearicum KPL3807 (as identified from the Prokka annotation) against the custom Corynebacterium genomes only had hits among the C. tuberculostearicum with 96–97% identity along 536–538 of 538 amino acids (Table S3G). Since nucleotide sugars are so universal, either UDP-galactose is sufficient for the other three Corynebacterium species, or they encode an enzyme other than Pgm that performs the second step in this module. Our KEGG analysis supports the need for future experimental metabolic studies with these Corynebacterium species.

Nasal Corynebacterium species can synthesize most essential amino acids.

This analysis estimated that all analyzed strains of these four common human nasal Corynebacterium species can synthesize 15 of the 20 standard amino acids. We detected complete biosynthetic modules for 11 amino acids in all 104 genomes, including the hydrophobic amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, methionine, valine, and tryptophan); the polar uncharged amino acids (threonine and serine); the charged amino acids (glutamate, arginine, histidine, lysine); and proline (Table 3; Fig. 4B). In these Corynebacterium, biosynthesis of methionine and arginine depends on aspartate as a precursor. For the five amino acids without KEGG modules, a manual search in KEGG and BioCyc databases for biosynthetic enzyme KOfams predicted that all four nasal Corynebacterium species plus C. glutamicumT and C. diphtheriaeT can generate the following three additional amino acids: alanine, glutamine, and glycine (File S1).

For aspartate and asparagine, the remaining two without their own biosynthetic KEGG modules, this search identified asparagine synthase (K01953), which interconverts these amino acids, in all of the genomes, so if one is available exogenously the other could be made. Of the pathways on KEGG for generating aspartate (https://www.genome.jp/pathway/map00250), these nasal Corynebacterium species only had KOfam hits for this interconversion of aspartate and asparagine. This implies nasal Corynebacterium species require an exogenous source of either aspartate or asparagine, but not both. KEGG lists similar annotations for interconversion in C. glutamicumT.

Our analysis predicted that all four common human nasal Corynebacterium species are auxotrophic for phenylalanine (M00024, M00910) and tyrosine (M00025, M00040). The biosynthetic KEGG modules listed for phenylalanine and tyrosine were incomplete/absent in the 104 nasal Corynebacterium genomes examined and in C. glutamicumT and C. diphtheriaeT. The pangenomes of the four nasal Corynebacterium species all lacked matches to enzymes needed for the last step in each module for synthesizing either phenylalanine (M00024, M00910) or tyrosine (M00024, M00040) from chorismate. The same two possible KOfam groups were missing: aromatic amino acid aminotransferase I / 2-aminoadipate transaminase (K00838) or aromatic-amino-acid transaminase (K00832).

Our analysis predicted all four species require exogenous phenylalanine, tyrosine, and either aspartate or asparagine. Of these four, mass spectrometry (MS) of aspirated human nasal secretions detects only phenylalanine (79); however, MS of nasal fluid collected with synthetic absorptive matrix strips detects aspartate, asparagine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine (80). Therefore, all four amino acids appear to be present in nasal secretions.

Predicted synthesis of methionine and cysteine varied by species.

All genomes had a complete module to convert glycerate-3P to serine (M00020), to convert serine to cysteine (M00021), and to convert aspartate to methionine (M00017). However, all the genes in assimilatory sulfate reduction module M00176 were absent in 30 of the 43 C. pseudodiphtheriticum genomes (all the U.S. strains and four strains from Botswana), and from C. diphtheriaeT. When performing an enrichment analysis within each of the four Corynebacterium species, only M00176 was significantly enriched in the Botswanan strains of 43 C. pseudodiphtheriticum (Table S3H). No other significant differences in KEGG module enrichment were detected in the other species’ pangenome (Table S3H-K). Assimilatory sulfate reduction is key to the production of cysteine and methionine since it takes environmental sulfate and converts it to a usable form in the cell (96). The complete absence of all the components of this KEGG module implies this subset of C. pseudodiphtheriticum strains cannot synthesize methionine or cysteine. Of note, C. glutamicumT, which lacks only the adenylyl sulfate kinase (cysC) component of this module, has proven assimilatory sulfate reduction capabilities via the fpr2-cysIXHDNYZ gene cluster (97). Moreover, all C. accolens, all C. tuberculostearicum, most C. propinquum (17/19), and 13 of 43 C. pseudodiphtheriticum genomes (13/17 strains from Botswana) had a completion score between 0.83 and 0.89 for this assimilatory sulfate reduction module (M00176). Like C. glutamicumT, these other strains all lacked the adenylylsulfate kinase cysC (K00860) that converts adenosine phosphosulfate into phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate (Fig. 4Civ), but our KEGG analysis detected cysN, cysD, cysH, and SIR (K00956, K00957, K00390, K00392). C. glutamicum cysH encodes an adenosine 5’-phosphosulfate (APS) reductase that can complement an E. coli cysC-deficient mutant (97). However, KEGG annotations currently lack the option for cysH to substitute for cysC, which explains why there is experimental evidence that C. glutamicumT performs assimilatory sulfate reduction but the KEGG module is marked as incomplete. Based on blastp results against the non-redundant protein sequences (nr) database, orthologs of C. glutamicum CysH are overwhelmingly present in the Order Mycobacteriales, which includes Corynebacterium (Table S3L). When we performed a targeted blastx on our analyzed Corynebacterium genomes using the translated amino acid sequence of C. glutamicum cysH, the percent identity was 68–70% for C. propinquum and a subset of C. pseudodiphtheriticum strains and 58–61% for C. accolens and C. tuberculostearicum strains along the full length (228–231) of the CysH amino acid sequence (Table S3M). Thus, many human nasal Corynebacterium strains likely also perform assimilatory sulfate reduction using CysH rather than CysC (Fig. 4Civ). These findings also indicate a recent and geographically localized loss of the assimilatory sulfate reduction module M00176 within the C. pseudodiphtheriticum phylogeny.

Methionine might also be acquired from the environment. The KEGG database contains three KOfam entries for methionine transporter genes: metN (K02071), metI (K02072), and metQ (K02073), which encode for the methionine ABC-transporter (MetNI) and substrate binding protein (MetQ). We found hits for all 3 of these genes in all 104 Corynebacterium and 27 D. pigrum strains, often with multiple hits per gene, confirming our earlier results from Brugger et al. (51) and predicting these nasal Corynebacterium can transport methionine from their environment.

DISCUSSION

Here, we analyzed strain genomes of four common Corynebacterium species including those of 87 distinct human nasal isolates collected in Africa and North America across the human lifespan. Phylogenomic analysis showed C. pseudodiphtheriticum displays geographically restricted strain circulation and this corresponded with a recent geographically restricted loss of the KEGG module for assimilatory sulfate reduction in strains isolated in the U.S, since this module was present in the other three species and most C. pseudodiphtheriticum strains from Botswana. Across the four species, genomic analysis revealed average genome sizes of 2.3 to 2.5 Mb, with the average CDS per genome ranging from 2105 to 2265 and with 72–79% of each individual genome encoding GCs of the shared conservative core genome of the respective species. For each species, the core genome size had leveled off while the pangenome remained open. An informative assignment to a definitive COG category was possible only for approximately 65% of the GCs in the persistent genome and 26–36% of the GCs in the accessory genome of each species, which points to the need for ongoing experimental research to identify the function of many bacterial GCs. GCs assigned to the COG categories for metabolism were enriched in the persistent genome of each species and all four species shared the majority (50 of 66) of complete KEGG modules identified, which implies limited strain- and species-level metabolic variation restricting the possibilities for strains to occupy distinct metabolic niches during the common occurrence of cocolonization of the human nasal passages. Corynebacterium species are often positively associated with Dolosigranulum in human nasal microbiota. We found human nasal Corynebacterium species have a broader metabolic capacity for biosynthesis of amino acids and cofactors/vitamins than D. pigrum. Our findings combined with data showing that the majority of adults likely host at least two Corynebacterium in their nasal passages points to the importance of future investigation into how Corynebacterium species interact with each other and with other microbionts in human nasal microbiota.

Our analysis predicts common human nasal Corynebacterium species all produce some compounds that D. pigrum cannot. This, combined with the positive association of these species in compositional studies, supports the possibility that Corynebacterium might cross-feed or serve as a source of nutrients for D. pigrum, and possibly other microbionts, in human nasal microbiota. These compounds include hydrophobic amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, methionine, valine and tryptophan); polar uncharged amino acids (threonine); charged amino acids (glutamate, arginine, histidine, lysine), and proline; along with the following cofactors/vitamins: biotin, heme, siroheme, lipoic acid, molybdenum cofactor, NAD, menaquinone, pantothenate, pyridoxal 5’-phosphate, riboflavin, and thiamine.

De novo cobamide biosynthesis is enriched in host-associated compared to environment-associated Corynebacterium species, with several human skin-associated Corynebacterium species encoding complete biosynthesis pathways (64, 78). Swaney, Sandstrom and Kalan used KOfamScan to identify the presence or absence of cobamide biosynthesis genes within genomes of diverse Corynebacterium species, exclusive of the four examined here (64). Checking for those same genes, we found only hits for genes encoding enzymes involved in biosynthesis of tetrapyrrole precursors (hemA, hemL, hemB, hemC, hemD, and cobA) and cobalamin nucleotide loop assembly (cobC) in our 104 Corynebacterium genomes. Moreover, none of the three strongly nasal-associated Corynebacterium species (C. accolens, C. propinquum or C. pseudodiphtheriticum) nor the common nasal- and skin-associated species, C. tuberculostearicum, encoded complete cobamide-production pathways (Table S4). Three incomplete modules for synthesis of cobalamin (vitamin B12), a member of the cobamide family of compounds, were detected in the 104 Corynebacterium genomes: 1) cobalamin biosynthesis (M00122) for cobyrinate a,c-diamide → cobalamin; 2) cobalamin biosynthesis, anaerobic (M00924) for uroporphyrinogen III → sirohydrochlorin → cobyrinate a,c-diamide; and 3) cobalamin biosynthesis, aerobic (M00925) for uroporphyrinogen III → precorrin 2 → cobyrinate a,c-diamide. Completeness scores for all three modules were very low, ranging between 0.083 and 0.286. In contrast, examining the four Corynebacterium species pangenomes for cobamide-dependent enzymes identified hits for ribonucleotide reductases (K00525, K00526) (84, 98) in all 104 Corynebacterium genomes. By analyzing the extent and distribution of cobamide production in 11,000 bacterial species, Shelton, Taga, and colleagues report 86% of bacteria in their dataset have at least 1 of the 15 cobamide-dependent enzyme families, but only 37% are predicted to synthesize their own cobamide (84). These data are consistent with human nasal Corynebacterium species requiring an exogenous source of cobamide compounds. C. acnes, which produces the cobamide vitamin B12 (cobalamin) (99) and is a highly prevalent and abundant member of human nasal microbiota, especially in adults (31), is a possible source.

Limitations of this study include the uneven representation of strains from the U.S. and Botswana for C. propinquum and C. accolens; the limited number of C. tuberculostearicum strains; the inherent limitations of KEGG analysis; and the predictive nature of genome-based metabolic estimation that requires future experimental validation. To our knowledge, this analysis includes the largest number of strain genomes for C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. propinquum, and C. accolens to date, with the aforementioned smaller number for C. tuberculostearicum. However, compared to the thousands of strain genomes that have been analyzed for nasal pathobionts, e.g., S. aureus (100), there are still a limited number of available genomes of nasal Corynebacterium species and a need to build large strain collections of human-associated Corynebacterium species to better assess the potential use of these strains for the promotion of human health. Similarly, although we included genomes for strains isolated from two continents and from a range of ages, the geographic sampling was limited compared to the distribution of human populations globally and there has yet to be a systematic large-scale sampling of nasal microbiota across the human lifespan.

Qualitatively, we isolated fewer C. tuberculostearicum from nasal swabs than expected based on its prevalence and relative abundance estimated in our earlier reanalysis of 16S rRNA gene V1-V3 sequences from human nasal samples (31). In contrast to using a single gene, here, we assigned isolates to C. tuberculostearicum based on WGS with an ANI of ≥ 95% to the type strain C. tuberculostearicum DSM 44922. Only a subset of our isolates from the US and Botswana with partial 16S rRNA gene Sanger sequences (approximately V1-V3) matching to C. tuberculostearicum met this criterion after WGS. This points to the existence of another common nasal Corynebacterium species that is closely related to C. tuberculostearicum. Recent human skin metagenomic analyses by Salamzade, Kalan and colleagues identify metagenome-assembled genomes and the strain genome LK1134 with ANI ≥ 95% to the genome called “Corynebacterium kefirresidentii” (101), which is not a validly published species, and show via phylogenomic analysis these are closely related to C. tuberculostearicum (34). Furthermore, using metagenomic analyses, they show sequences matching the “C. kefirresidentii” genome are more prevalent on nasal and nearby facial skin sites, whereas C. tuberculostearicum is more prevalent and at higher relative abundance on foot-associated skin sites (34). Future work to validly name the species currently identified by the genome called “C. kefirresidentii” with designation and deposition of a type strain in publicly accessible stock centers is critical for experiments seeking to identify the function of this species in human nasal microbiota.

Isolation and whole genome sequencing of multiple strains for microbial species commonly detected in the human microbiome, such as this one, is an ongoing effort across multiple body sites. Collections of genome-sequenced strains from the microbiota are a critical resource for experimentally testing hypotheses generated from metagenomic and metatranscriptomic studies to identify the functions of human microbionts and mechanisms by which they persist in the microbiome. The Human Oral Microbiome Database (eHOMD) is an early and ongoing example of a body-site focused resource for the human microbiome based on a combination of culture-dependent and -independent data (102). Originally focused on the oral cavity, eHOMD now serves the full human respiratory tract (31). More recently, Saheb Kashaf, Finn, and colleagues established the Skin Microbial Genome Collection (SMGC), a combined cultivation- and metagenomic-based resource for the human skin microbiome (78). These well-curated, body-site focused databases serve a critical role in advancing microbiome research, including their importance in shedding light on so-called microbial and metagenomic “dark matter.” The data we presented here serves as a foundational resource for future genomic, metagenomic, phenotypic, metabolic, functional, and mechanistic research on the role of nasal Corynebacterium species in human development and health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collecting new nasal Corynebacterium sp. isolates.

The U.S. Corynebacterium strains with KPL in their name were collected in Massachusetts, USA under a protocol approved by the Forsyth Institutional Review Board (FIRB #17–02) as described previously (68). In brief, adults and children participating in scientific outreach events in April 2017 and 2018 performed supervised self-sampling of their nostrils (nasal vestibule) with sterile swabs. They then inoculated their swab onto up to two types of agar medium: 1) brain heart infusion with 1% Tween80 (BHIT) and 25 microgram/ml fosfomycin (BHITF25) to enrich for Corynebacterium sp. and/or 2) BBL Columbia Colistin-Nalidixic acid agar with 5% sheep’s blood (CNA BAP). These were incubated at 37°C for 48 hrs under either atmospheric (BHITF25) or 5% CO2-enriched (CNA BAP) conditions. We selected colonies with a morphology typical of nasal Corynebacterium species and passed each two to three times for purification on BHIT with 100 ug/ml fosfomycin (BHITF100) at 37°C prior to storage in medium with 15–20% glycerol at −80°C. (Isolates from 2017 were picked from growth on BHITF100 at 37°C under atmospheric conditions that had been inoculated from sweeps of the original mixed growth on agar medium and stored at −80°C.)

The majority of the Corynebacterium strains with MSK in their name were cultured from nasopharyngeal swab samples collected from mothers and infants in a birth cohort study conducted in Botswana, as previously described (13), with a small number also collected from mid-turbinate nasal swab samples from patients cared for within the Duke University Health System (MSK074, MSK075, MSK076, MSK079, and MSK080). This work was reviewed and considered exempt by the Duke Health Institutional Review Board (Pro00102629). Bacteria were cultivated and isolated as previously described (13).

Selection of nasal Corynebacterium isolates for Illumina sequencing.

For each KPL-named new isolate, Sanger sequencing (Macrogen, USA) was performed using primer 27F on a V1-V3 16S rRNA gene colony-PCR amplicon (GoTaq Green, Promega) of primers 27F and 519R. We assigned each initial isolate to a genus and a putative species based on blastn of each sequence against eHOMDv15.1 (31). We then selected a subset of these isolates for whole genome sequencing (WGS). For MSK-named new isolates, all isolates preliminarily assigned to Corynebacterium based on MALDI and/or Sanger sequencing of V1-V3 16S rRNA gene underwent WGS.

Genomic DNA extraction.

We extracted genomic DNA (gDNA) from the KPL-named U.S. strains using the MasterPure Gram Positive Genomic DNA Extraction Kit with the following modifications to the manufacturer’s protocol: 10 mg/mL lysozyme treatment at 37°C for 10 min and 2× 30 sec bead beat in Lysing Matrix B tubes (MP Biomedicals) at setting 6 on a FastPrep24 (MP Bio) with 1-minute interval on ice. To assess gDNA quality, we performed electrophoresis on 0.5% TBE agarose gel, used a NanoDrop spectrophotometer to quantify 260/280 and 260/230 ratios, and used a Qubit Fluorometric Quantification (Invitrogen) to measure concentration. We extracted gDNA from the MSK-named strains collected in Botswana and North Carolina using the Powersoil Pro extraction kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentrations were determined using Qubit dsDNA high-sensitivity assay kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Whole genome sequencing and assembly.

For the KPL-named U.S. isolates, Nextera XT (Illumina) libraries were generated from gDNA. Each isolate was sequenced using a paired-end 151-base dual index run on an Illumina Novaseq6000 at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Center. The reads were subsampled to achieve 80x coverage and then assembled with SPAdes (version 3.13.0) (103) and polished using Pilon (version 1.22) (104). For the MSK-named isolates, which are mostly from Botswana, library preparation was performed using DNA Prep Kits (Illumina) and these libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 instrument (Illumina) configured for 150 base pair paired-end reads. Adapter removal and read trimming were performed using Trimmomatic version 0.39 (105) to a Phred score of 30 across a 4-bp sliding window. Surviving reads shorter than 70 bp were discarded. The final quality of reads was assessed using FastQC version 0.11.9. Assembly was performed using SPAdes version 3.15.3 (106). The completeness of the genomes was evaluated with checkM version 1.1.3 (107) and all genomes with a completeness less than 95% were discarded. Genomic data are deposited under BioProjects PRJNA842433 for the KPL-named isolates (which are a subset of 94 Corynebacterium isolated in MA, USA) and PRJNA804245 for the MSK-named isolates (which are a subset of 71 genomes isolated from Botswana and the Duke University Health System). Table S1 includes GenBank IDs.

Selection of strain genomes for pangenomic analysis.

To the 165 assemblies mentioned in the previous section, we added another 16 KPL-named Corynebacterium sp. nasal-isolate genomes originally sequenced as part of the HMP and deposited by the Broad at NCBI to consider for analysis (108). Furthermore, 31 reference assemblies for relevant Corynebacterium species, including the genome of the type strain of C. propinquum, C. pseudodiphtheriticum, C. accolens, and C. tuberculostearicum plus 3 strain genomes of C. macginleyi, were downloaded from NCBI using the PanACoTA v1.4.1 (109) `prepare -s` subcommand. We used default parameters such that genomes with MASH distances to the type strain outside of the range 1e-4 to 0.06 were discarded to avoid redundant pairs or mislabeled assemblies and low-quality assemblies based on L90 ≤ 100 and number of contigs ≤ 999 were filtered out. The collected 212 assemblies were filtered using the `prepare --norefseq` subcommand as above to select higher quality assemblies (L90 ≤ 100 and number of contigs ≤ 999) and to eliminate redundant genomes defined by a MASH distance < 10−4 keeping the genome with the highest quality score from each redundant set. Finally, we confirmed the species-level assignment of our nasal isolates, and the nontype reference strains, based on an ANIb (nucleotide) of ≥ 95% for all shared CDS regions compared to the respective type strain of each species using GET_HOMOLOGUES (see below). For each species, this resulted in a set of distinct strain genomes (including the type strain) that we used for subsequent analyses, which totaled to 104 genomes: 19 C. propinquum genomes, 43 C. pseudodiphtheriticum genomes, 34 C. accolens genomes, and 8 C. tuberculostearicum genomes. Table S1 contains (A) a list of these 104 strain genomes selected for further analysis plus 3 C. macginleyi reference strains, and (B) the all-by-all MASH distance analysis result of the PanACoTA analysis for all 107 genomes.

Determination of the conservative core genome.