Abstract

The decomposition of cobalt carbide (Co2C) to metallic cobalt in CO2 hydrogenation results in a notable drop in the selectivity of valued C2+ products, and the stabilization of Co2C remains a grand challenge. Here, we report an in situ synthesized K-Co2C catalyst, and the selectivity of C2+ hydrocarbons in CO2 hydrogenation achieves 67.3% at 300°C, 3.0 MPa. Experimental and theoretical results elucidate that CoO transforms to Co2C in the reaction, while the stabilization of Co2C is dependent on the reaction atmosphere and the K promoter. During the carburization, the K promoter and H2O jointly assist in the formation of surface C* species via the carboxylate intermediate, while the adsorption of C* on CoO is enhanced by the K promoter. The lifetime of the K-Co2C is further prolonged from 35 hours to over 200 hours by co-feeding H2O. This work provides a fundamental understanding toward the role of H2O in Co2C chemistry, as well as the potential of extending its application in other reactions.

A Co2C catalyst is in situ synthesized and stabilized by H2O and K promoter for CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ hydrocarbons.

INTRODUCTION

The continuously increasing greenhouse gas CO2 levels originated from human activities have caused a series of environmental issues, including sea level rises, heat waves, and ocean acidification (1). Among the strategies considered, catalytic CO2 reduction with green H2, which is generated from water splitting by renewable energy, to valuable C2+ hydrocarbons (HCs) provides a potential technology to reduce CO2 concentration and an alternative nonpetroleum-based production route toward light olefins (C2 ~ C4=) and liquid fuels (C5+) (2, 3). However, the chemical inertness of CO2 molecules (C═O bond of 750 kJ mol−1) and the high energy barrier of C─C coupling are detrimental to the formation of C2+ products (4, 5). Accordingly, it is highly attractive and challenging to develop effective catalysts for selective CO2 conversion to C2+ HCs.

Much attention has been paid to using CO Fischer-Tropsch synthesis (CO-FTS) catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation, and, in general, CO2 is initially converted to CO intermediate via a reverse water gas shift (RWGS) reaction, followed by CO hydrogenation to C2+ HCs (6). For instance, iron carbide (FeCx) exhibits high activity for COx hydrogenation to olefins in a high-temperature range (320° to 350°C) (7–9). Cobalt carbide (Co2C) is also a promising catalyst for COx conversion owing to its adequate activation of C═O bonds and promoting effect on C─C coupling (10). Notably, it has distinct features in different reaction atmospheres. As for CO-FTS, nanoprism Co2C with preferentially exposed (101) and (020) facets has been proven to be responsible for the synthesis of C2 ~ C4=, while electronic (alkali metal) and structural promoters (Mn and Ce) are instrumental in its morphological control (11–15). The synthesis of Co2C is commonly divided into two steps, including an initial reduction and carburization in syngas (CO and H2) or CO. Wavelet transform and linear combination fitting results of in situ x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) indicate that cobalt oxide (CoO) is first reduced to metallic cobalt (Co0), and then carburized to Co2C (16). Moreover, Co2C is commonly used below 260°C and at near atmospheric pressure in CO-FTS to avoid its decomposition to Co0 and graphite (17). Despite numerous efforts, Co2C is unstable and still underutilized for CO2 hydrogenation (18, 19). Compared with CO-FTS, the conversion of equimolar CO2 consumes more H2, and the presence of excess H2 and CO2 accelerates the decomposition of presynthesized Co2C (18). Besides, the activation of inert CO2 often requires a high temperature, and it thus puts forward higher requirements for the thermal stability of Co2C. As a result, the Co2C catalyst tends to partially decompose to Co0 under CO2 hydrogenation, which leads to a rapid side reaction toward CH4 (20). In recent studies, SiO2 support interacted with Co2C was used for improving the stability, but a reconstruction to Co0 occurred while C1 products dominate under reaction conditions (21). Co2C with different morphologies was prepared from the ZIF-67 precursor by Zhang et al. (22) for RWGS reaction, but the atmospheric pressure condition only enables a reduction of CO2 to CO and limits the selectivity to C2+ HCs. The facile synthesis and stabilization of Co2C under a C-lean and H-rich atmosphere at higher temperatures and pressure are major bottleneck for its catalytic application in CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ HCs.

H2O is a common impurity for CO2 capture from flue gas (23), and more H2O is generated in CO2-FTS compared with CO-FTS; therefore, its impact on the catalyst structure and performance needs to be pinpointed. As for Fe-based catalysts, H2O-induced oxidation causes the evolution of FeCx to iron oxides (FeOx) and a decrease of the activity in both CO- and CO2-FTS (8, 24). H2O has also been proven as a poison owing to its competitive adsorption and oxidation of Co0 catalyst in CO-FTS (25–27). Thus, the rapid removal of H2O boosts the syngas conversion to C2+ HCs (28). However, up to now, the effect of H2O on Co2C catalyst is still ambiguous in CO2 hydrogenation, clarification, and optimization which is of importance to improving the practical application.

Here, we report the in situ synthesis and stabilization of Co2C with H2O from a K-modified Co3O4 precursor for CO2 hydrogenation. In situ x-ray diffraction (XRD) and simulated results of chemical potential corroborate that the carburization route derived from CoO dominates under CO2 hydrogenation conditions, while the reaction atmosphere in conjunction with the K promoter is important for the stabilization of Co2C. Notably, co-feeding 2 volume % of H2O accelerates the carburization by enhancing the formation of surface carboxylate, which prefers to further split for following C permeation. The K promoter also endows the adsorption of C atoms on the CoO surface, favoring the subsequent carburization. CO2 converts to C2+ HCs via CO* intermediate derived from carbonate splitting on K-Co2C catalyst, and a selectivity to C2+ HCs up to 67.3% is achieved at 300°C, 3.0 MPa. Furthermore, H2O (0.5 volume %) is applied to inhibit the decomposition of surface Co2C and markedly prolongs the catalyst lifetime from 35 to over 200 hours. This work reveals a unique promoting role of H2O in Co2C-catalyzed CO2 hydrogenation and provides a mechanistic understanding of the formation and evolution of Co2C. It is expected to advance the application of Co2C in CO2 hydrogenation, and potentially other reactions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis, catalytic performance, and kinetics

As displayed in Fig. 1A, Co3O4 and K-modified Co3O4 precursors were prepared via a citric acid–induced sol-gel method and subsequent incipient wetness impregnation (IWI) using the solution of K2CO3 (0.98 wt %; details in Materials and Methods). XRD patterns and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) results confirm that the foamy gels were completely decomposed to Co3O4 after the calcination at 450°C (fig. S1). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images on Co3O4 and K-Co3O4 illustrate that there is no substantial change in the average particle size (21 to 24 nm, beyond the sensitive size range in CO2 hydrogenation) and morphology of Co3O4 with the K modification (fig. S2). The particle size of K-Co3O4 exhibits a narrower distribution owing to the secondary calcination. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mappings confirm that the K promoter is uniformly dispersed across the Co3O4 surface (fig. S3). These precursors were used in CO2 hydrogenation reaction at 300°C, 3.0 MPa with a space velocity of 6000 ml g−1 hour−1. We collected the spent samples, which were tested for 3 hours of CO2 hydrogenation, after careful passivation. The characteristic XRD peaks for spent samples derived from Co3O4 and K-Co3O4 are assigned to the phases of metallic Co (Co0), which consists of face center cubic–Co and hexagonal closest packed (hcp)–Co, and Co2C, respectively (these two spent samples are denoted as Co0-t and K-Co2C, respectively) (Fig. 1A). It indicates that these two phases were in situ generated under the reaction conditions.

Fig. 1. Catalyst synthesis and catalytic properties.

(A) Scheme for the reaction-induced in situ synthesis and XRD patterns of K-Co2C and Co0-t samples. (B) Catalytic performance on Co0-t and K-Co2C at 300°C, 3.0 MPa, space velocity = 6000 ml g−1 hour−1, H2/CO2 = 3. (C) C2+ HCs space-time yield (STY) and catalytic performance for adjusted K loadings and alkali metal promoters at the same reaction conditions. (D) Catalytic performance at optimized reaction conditions, Co0-t: H2/CO2 = 2, 42,000 ml g−1 hour−1; K-Co2C: H2/CO2 = 2, 4,500 ml g−1 hour−1. (E) Activation energies for CO2 conversion and C2+ HCs or CH4 formation on K-Co2C. (F) Activation energies on Co0-t sample. (G) CO2 and H2 reaction orders evaluated at 260°C, 3.0 MPa. wt %, weight %; a.u., arbitrary units.

Some differences in the catalytic performance were observed on Co0-t and K-Co2C. As shown in Fig. 1B, K-Co2C offers a selectivity to C2+ HCs of 46.5%, whereas it is only 6.0% on Co0-t. High-value products C2 ~ C4= and C5+ occupy 13.4 and 16.5% of K-Co2C with an olefin/paraffin (O/P) ratio of 0.8 and a chain growth factor α of 0.53. In contrast, methane dominates (selectivity as 94.0%) on Co0-t, while ethane is the only C2+ product. The normalized space-time yields (STYs) of C2+ HCs based on catalyst mass and surface area reach 7.7 mmol gcat−1 hour−1 and 0.31 mmol m−2 hour−1 on K-Co2C sample, while those on Co0-t are 1.7 mmol gcat−1 hour−1 and 0.08 mmol m−2 hour−1, respectively. We further modulated the K content and found that only K-Co2C (K fraction as 0.98 wt %) delivered a moderate conversion (38.2%) and high selectivity and STY to C2+ HCs, while 0.49% K-Co3O4 and 1.96% K-Co3O4 samples only yield 2.2 and 1.8 mmol gcat−1 hour−1, respectively (Fig. 1C and table S1). Further investigations on Na- and Cs-modified samples show decreased selectivity to C2+ HCs of 37.0 and 42.8%, while their STYs are 6.4 and 5.9 mmol gcat−1 hour−1, respectively. In addition, the reaction temperature and pressure on K-Co2C were optimized (table S2). We found that both CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity increase with the temperature (260° to 340°C), indicating that a high-reaction temperature promotes the CO2 activation but also boosts the deep hydrogenation to CH4. The optimum yield to C2+ HCs and those to C2 ~ C4= and C5+ (2.2 and 2.7 mmol gcat−1 hour−1) were obtained at 300°C (fig. S4). Tests at various pressures show that the CO2 conversion and C2+ HCs selectivity monotonically increase with the reaction pressure, whereas CO selectivity decreases (fig. S5A). Under pressurized conditions (0.8 to 3.0 MPa), more C2+ HCs were detected (above 34.5%), and all the spent samples show well-defined reflections of Co2C. In contrast, the sample evaluated at atmospheric pressure (0.1 MPa) consists of CoO and Co2C, while CO is the dominant product (61.8%), revealing that the reaction pressure affects the carburization and C─C coupling (fig. S5B). Considering that Co2C tends to decompose to Co0 at a high temperature (above 260°C) and a high pressure (above 2 MPa) in CO-FTS (29), this in situ synthesized K-Co2C catalyst operated at 300°C and 3.0 MPa extends its application in catalytic CO2 conversion.

To inhibit the deep hydrogenation of the C1 intermediate and increase the proportion of valuable C2+ HCs, we further optimized the H2/CO2 ratio to 2/1. At a comparable conversion (24.2 and 21.6%), Co0-t (42,000 ml g−1 hour−1) and K-Co2C (4500 ml g−1 hour−1) exhibit the selectivity to C2+ HCs as 3.3 and 67.3%, respectively (Fig. 1D). The selectivity to C2 ~ C4= and C5+ on K-Co2C reach 31.6 and 28.7% with an O/P ratio of 4.5. The detailed distribution of C2+ HCs is shown in fig. S6 and table S3. The decreased space velocity and H2/CO2 ratio favor the carbon chain growth (α of 0.59) and inhibit the rehydrogenation of olefins, leading to a higher proportion of valuable C2 ~ C6=. Kinetic analysis was conducted at high space velocities to get insights on enhanced C2+ HCs generation on K-Co2C. The apparent activation energies (Ea) for CH4 and C2+ HCs generation were estimated as 96.7 ± 4.1 kJ mol−1 and 50.1 ± 1.5 kJ mol−1 on K-Co2C versus 80.4 ± 4.6 kJ mol−1 and 92.9 ± 4.8 kJ mol−1 on Co0-t, revealing that C2+ HCs formation is more facile, whereas CH4 formation is inhibited on K-Co2C (Fig. 1, E and F). Apparent reaction orders on K-Co2C (CO2 α1 = 0.48 ± 0.03 and H2 β1 = 0.98 ± 0.05) and Co0-t (CO2 α2 = 0.88 ± 0.01 and H2 β2 = 0.32 ± 0.02) further evidence that the enhanced CO2 or suppressed H2 activation profit the C2+ HCs formation instead of CH4 on K-Co2C (Fig. 1G) (30). Moreover, compared with K-Co2C, the similar CO2 reaction order (α3 = 0.47 ± 0.01) and the evidently increased H2 reaction order (β3 = 1.34 ± 0.04) of 1.96% K-Co3O4 (fig. S7) suggest that the excessive K promoter inhibits the H2 activation, instead resulting in the declined catalytic performance. We further investigated the specific properties of CO2 and H2 adsorption and activation on Co2C and Co surfaces using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Compared with Co, the CO2 adsorption and dissociation energies on the Co2C surface decreased from −0.08 to −0.26 eV, and −1.19 to −1.57 eV, respectively (fig. S8A). Thus, CO2 adsorption and activation are enhanced on Co2C. There is essentially no difference between the molecular adsorption energies of H2 on the two surfaces (fig. S8B). However, the dissociation energy of H2 on the Co surface (−1.22 eV) is exothermic, whereas the dissociation energy on Co2C (0.04 eV) is energetically less favorable.

Structural characterization

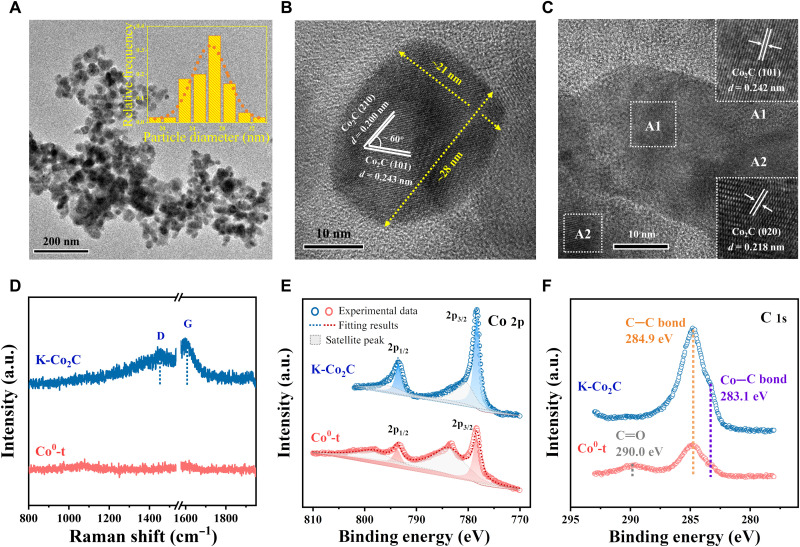

The specific surface areas of Co0-t and K-Co2C are 20.9 and 24.8 m2 g−1 (table S4), and their average particle sizes are 23.2 ± 0.1 and 26.6 ± 0.2 nm as estimated from the XRD results, respectively. TEM and representative HRTEM images show that K-Co2C represents a cylindrical morphology. The interplanar distances of 0.200, 0.218, and 0.243 nm match the (210), (020), and (101) planes of Co2C, respectively (Fig. 2, A to C) (31). We verified that the K promoter is still uniformly dispersed on the Co2C surface (fig. S9), suggesting that there is no obvious migration or agglomeration of K during the reaction. As for Co0-t, the (002) and (100) planes of hcp-Co were clearly observed (fig. S10). Previous DFT results by Zhang et al. (32) suggest that (101) and (020) facets of Co2C compete for CHx* coupling, leading to the high selectivity to C2+ HCs on K-Co2C. Ultraviolet (UV) Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 2D) with a 320-nm laser was used to probe the information of C species at about 10 nm in depth without the interference of fluorescence (33). Two Raman shifts observed on K-Co2C of ~1453 and ~ 1606 cm−1 are ascribed to the D and G bands of C species in Co2C, which represents the A1g vibration of disordered graphite and E2g vibration of graphitic carbon, respectively (21, 34). The ID/IG value (calculated using the deconvoluted peak area) for K-Co2C is ~1.38, suggesting the low disorder degree and surface energy (21). In contrast, no signal was detected on the metallic Co0-t sample.

Fig. 2. Structural characterizations of spent catalysts.

(A) TEM images and particle size distribution of K-Co2C. (B and C) HRTEM images of K-Co2C. (D) Ultraviolet Raman spectra of K-Co2C and Co0-t. Quasi in situ x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of K-Co2C and Co0-t (E) Co 2p spectra and (F) C 1s spectra.

Considering the carbide is sensitive to air, the surface properties of spent catalysts were further investigated using quasi in situ x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) without exposure to air. The K 2p features of K+ species in K2CO3 were observed at 296.8 and 294.2 eV on K-Co2C (fig. S11) (35). The binding energies of Co 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 in Co2C (793.5 and 778.3 eV on K-Co2C) and Co0 (793.6 and 778.4 eV on Co0-t) are similar, except for the signals at 798.0 and 783.5 eV associated with the superposition of Co0 satellite peaks and Co2+ 2p peaks (Fig. 2E) (36). The Co2C species on the surface of K-Co2C was also identified according to the signal of the C 1s band at 283.1 eV, assigned to the Co─C bond (Fig. 2F). The characteristic peaks of the C═O group and the C─C bond originated from the surface adsorbed species appear at 290.0 and 284.9 eV, respectively (22). The surface C/Co molar ratio, which was estimated on the basis of the deconvoluted results, on K-Co2C (0.27) is much higher than that on Co0-t (0.12), suggesting the enhanced carburization with K modification.

Adsorption properties and reaction mechanism

Temperature programmed desorption (TPD) of CO2, CO, and H2 combined with online mass spectrometry (MS) was performed to characterize the adsorption properties (fig. S12). Compared with Co0-t, K-Co2C shows an enhanced medium-strong adsorption of CO2 and CO (300° to 450°C), but a diminished adsorption of H2. The medium-strong adsorbed CO2 and CO species on K-Co2C, which is more inclined to be activated and involved in the subsequent conversion, can create a relatively C-rich and H-lean environment, inhibiting the deep hydrogenation while promoting the C─C coupling (37). In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was carried out to gain insight into the reaction pathways, and the detailed peak assignments are listed in table S5. As shown in Fig. 3A, the spectra for CO2 pre-adsorbed on K-Co2C were collected during the pressurization of CO2 to 1.2 MPa at 50°C and subsequent heating to 260°C. CO2 was initially activated as monodentate carbonate (m-CO32−, at 1511, 1437, 1395, and 1278 cm−1) and bidentate carbonate (b-CO32−, at 1676 and 1625 cm−1) on the K-Co2C surface (38–41). The features of adsorbed CO (COads) on Co2C (2078 cm−1) and Co0 (2059 cm−1) were detected once the pressure was increased to 0.6 MPa, and that of bicarbonate (HCO3−, at 1606 cm−1) emerges at 200°C, 1.2 MPa, indicating that the residual H species originated from the pretreatment or the hydroxyl group assists in the surface reaction (38). This COads species reveals that, on the K-Co2C surface, a small amount of CO2 preferentially converted to CO at mild conditions (38). After switching to H2 (Fig. 3B and fig. S13A), the features of bidentate formate (b-HCOO*, the stretching and bending vibrations of C─H band at 2766, 2680, and 1400 cm−1, and the vibration of OCO group at 1591 cm−1) and that of generated gaseous CO (COgas, at 2178 and 2111 cm−1) and CH4 (3015 and 1306 cm−1) and the vibrations of C─H bonds in C2+ HCs as CH3 (2956 cm−1) and CH2 (2929 cm−1) (the enlarged spectra are shown in fig. S13B) were observed (39, 42). The varying tendency of above species as determined by the featured peak (table S6) intensity with time is shown in Fig. 3C. It can be seen that the CO32− rapidly reduces starting at 50°C, 1.2 MPa with an increasing intensity of COads, indicating that CO32− initially converts to COads without the H assistance. Surface HCO3− has gradually accumulated and reaches a steady state after 260°C, 1.2 MPa. The introduction of H2 results in the reduction of COads and m-CO32− with an increase of CHx* from 0 to 30 min and continuous generation of COgas and HCs. Moreover, the intensity of b-HCOO* increases after H2 addition but its further conversion is not observed. It is speculated that COads derived from CO32− is an important intermediate for CHx* generation, which is further coupled to C2+ HCs on K-Co2C catalyst, whereas the HCO3− and b-HCOO* seem acting as spectators. By comparison, as for Co0-t catalyst (figs. S14 and S15), the intensities of b-HCOO* rapidly decreased after switching to H2, while those of monodentate formate (m-HCOO*) and product CH4 simultaneously increased, indicating that the generation of CH4 mainly undergoes the b-HCOO*–mediated pathway. Moreover, the signal of COads also emerged during CO2 adsorption (200° to 260°C) and quickly vanished after the H2 introduction. It reveals that the COads species is also possibly involved in the CH4 formation.

Fig. 3. Reaction mechanism studies.

In situ DRIFTS spectra on K-Co2C for (A) CO2 pre-adsorption. (B) Intermediates conversion with switching to H2 at 260°C, 1.2 MPa. (C) Evolution of surface species according to the intensity of infrared featured bands.

In situ synthesis and stabilization of Co2C

We resorted to in situ XRD and theoretical calculations to shed light on the structural evolution of Co-species during the reaction. The reduction properties were first determined as discerned by the in situ XRD patterns of as-prepared Co3O4 and K-Co3O4 in H2 (fig. S16). We found that K addition increased the complete reduction temperature from 300° to 360°C, suggesting that, to some extent, it inhibits the reduction of cobalt oxide toward the Co0. Under the CO2 hydrogenation atmosphere (Fig. 4A), the Co3O4 modified with K was first reduced to CoO and then carburized to Co2C at 260°C within 2 hours, and the reflection of Co0 was absent throughout the test. In combination with the semiquantitative XPS analysis (Fig. 2, E and F) that the surface C/Co ratio (0.27) on K-Co2C is relatively lower than the standard stoichiometric coefficient in Co2C (0.50), we speculate that, with K modification, the Co2C was in situ generated, followed by its partial decomposition to Co0 on the catalytic surface. Regarding that Co0 species generally participates in deep hydrogenation to CH4, a strategy against this decomposition is still required. In comparison, the Co3O4 without K was reduced to CoO and then directly to Co0 at 260°C within 50 min (fig. S17 and green arrows in Fig. 4B). Ab initio thermodynamics methods were applied to derive the phase diagram and depict the structural evolution of the catalyst. The chemical potentials for C (μC) and O (μO) are determined according to the gas-phase composition and reaction conditions (43). As displayed in Fig. 4B, the initial reaction condition is located at the red circle (μO = −7.02 eV, μC = −9.69 eV) which is near the computed boundary of the CoO phase. This μO value is below the Co3O4 phase. Therefore, once Co3O4 is exposed to the environment, a reduction in the CoO will occur. During the reaction, μO decreases, while μC increases due to the CO generated from CO2 reduction. As a result, the final chemical potentials migrate to the black circle (μO = −7.79 eV, μC = −8.16 eV), which is inside the domain of Co2C, suggesting that its formation from CoO is thermodynamically favorable under reaction conditions. Considering that the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) is more negative for the carburization from CoO than that from Co0 (fig. S18), and no bulk Co0 was observed during the evolution (Fig. 4A), we speculate that the thermodynamic advantages directly propel CoO into carburization without the reduction to Co0. We then investigated the structural evolution in CO2 hydrogenation for the K-Co0 sample, which was obtained from the decomposition of K-Co2C. The in situ carburization of metallic cobalt toward Co2C was also observed, exhibiting the gradually increased C2+ HCs selectivity and reduced CH4 selectivity along with the reaction (fig. S19). The CH4 dominates in the initial products of K-Co0 [time on stream (TOS) = 1 hour] or Co0-t samples, suggesting that the introduction of the K promoter does not substantially influence the product selectivity. The temperatures for the emergence of Co2C reflections and the disappearance of Co0 reflections increase to 270° and 330°C, respectively (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the synthesis of Co2C from Co0 precursor requires a high temperature for the C permeation into the Co lattice. We are thus confident that the in situ synthesis of Co2C in CO2 hydrogenation starts from K-modified CoO (blue arrows in Fig. 4B) instead of Co0. By comparison, the syngas preferentially induces the reduction to Co0, while the following carburization originates from Co0 (16). The replacement of CO with CO2 results in an increased μO, favoring the unique CoO route for the synthesis of Co2C. Moreover, this oxide-mediated carburization is different from that of iron catalysts although their carbides have many similarities. Metallic iron is more advantageous than its oxide for the formation of FeCx, and this key difference is helpful to understand the distinct evolution and deactivation pathways for cobalt- and iron-based catalysts in COx conversion (44, 45).

Fig. 4. Structural evolutions and theory calculations.

(A) In situ XRD patterns of K-Co3O4 in CO2 hydrogenation at 0.8 MPa. (B) Phase diagram of Co-O-C trinary system derived from the DFT energies of bulk crystals. (C) In situ XRD patterns of K-Co0 sample in CO2 hydrogenation at 0.8 MPa; the K-Co0 sample was synthesized from the decomposition of K-Co2C in H2 at 340°C, 0.8 MPa. In situ XRD patterns of K-Co2C (D) in pure CO2 at 0.8 MPa, (E) in 25 volume % H2O/N2 at 0.1 MPa. Potential energy profiles. (F) CO2 dissociation to CO* and O* on Co2C (101) surface with or without K2O.

Structural stability is a key factor for catalysts. As evidenced by the in situ XRD patterns in N2 at 0.8 MPa (fig. S20), K-Co2C is thermally stable below 340°C without bulk decomposition. Its stability in the presence of reactants and products is also important but still uncertain. Co2C is considered a metastable phase under the H-rich environment, and, from the in situ XRD results of K-Co2C in pure H2, it can be clearly seen that the transition of Co2C to Co0 occurs at 290°C (fig. S21). A recent report has proven that CO2 adsorbs on the surface as carboxylate (CO2δ−) and then splits to C* in the presence of H2, enabling the following C permeation (22). We performed the in situ XRD investigations on K-Co2C in pure CO2 and found that excessive CO2 also removes the C from Co2C at 300°C (Fig. 4D). Previous results have shown that H2O can oxidize hcp-Co to CoO or cobalt hydroxide but its effect on Co2C is unclear (46). We investigated the evolution of K-Co2C in 25 volume % (the theoretical value of volume fraction and the same as below) H2O/N2 and found that excessive H2O causes the transition of Co2C to hcp-Co in the range of 280° to 310°C (Fig. 4E). There is no obvious oxidation in bulk below 340°C, possibly originated from the fast O* removal with K-promoting effect (47). When the H2O content was decreased to 5%, this transition intensively occurred in the temperature region of 330° to 340°C (fig. S22), which is higher than that with co-feeding 25% H2O, implying that the H2O concentration also has an impact on the decomposition of Co2C. Inspired by the above findings, we believed that the single reactant or product (H2O) of high concentrations could destroy the K-Co2C but a unique balance between them in CO2 hydrogenation presents an opportunity for its stabilization. We further inquired into the effect of the K promoter. We prepared a Co2C sample without K (denoted as Co2C-t) through a reduction-carburization procedure from Co3O4. However, it rapidly decomposed to hcp-Co at 260°C in CO2 hydrogenation within 20 min as confirmed by the in situ XRD results (fig. S23). Moreover, the DFT results on the Co2C (101) surface reveal that with the modification using the K2O promoter, the direct splitting of CO2 to CO is more facile, considering that the energy barrier and energy of reaction (Ereaction) reduce from 1.10 to 0.56 eV and −0.36 to −1.04 eV, respectively (Fig. 4F). Since CO2 is adverse to the stabilization of Co2C whereas CO enhances the carburization, the promoting effect on CO2 direct dissociation here is also important for stabilizing the Co2C. Hence, we reveal that the reaction atmosphere in conjunction with the K promoter is crucial in the stabilization of Co2C.

H2O promoted carburization and stabilization

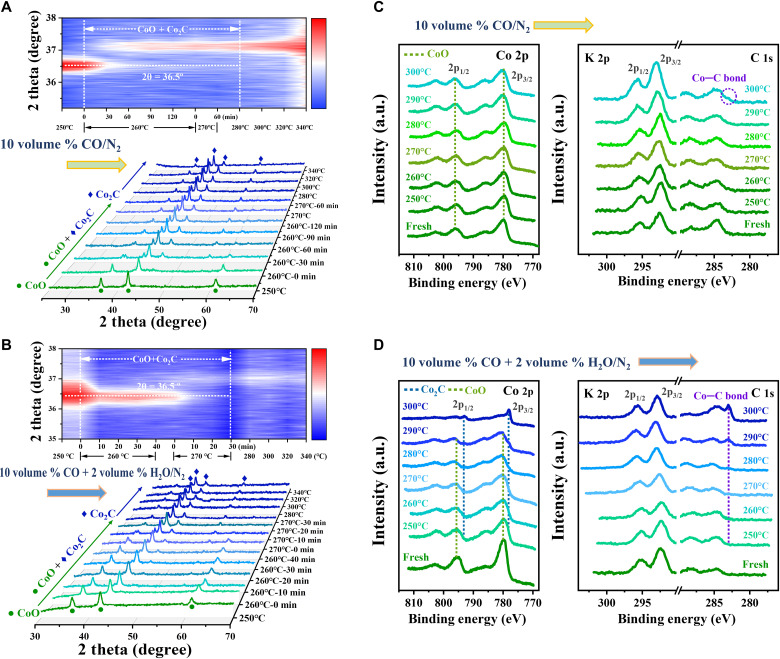

Since H2O is a common impurity for CO2 capture and more H2O is generated in CO2-FTS compared with CO-FTS, we further delve into its influences on the carburization and the catalytic reaction. We simulated the carburization from K-CoO in 10% CO/N2 and, as shown in Fig. 5A, in situ XRD results demonstrate that the transformation of CoO to Co2C started at 260°C and finished at 280°C as evidenced by the vanishing CoO feature at 36.5°. While 2% H2O was co-fed (at 0.1 MPa, Fig. 5B), despite the constant temperature for the beginning of carburization at 260°C, the transition of CoO to Co2C was accomplished at 270°C. Once the H2O content was increased to 5%, the onset and end temperatures for the carburization shifted to 290° and 300°C, respectively (fig. S24). As stated above, a moderate amount of H2O facilitates the carburization of K-CoO and reduces the carburizing temperature, while its content is crucial. Most previous studies reported the negative effect of H2O on the active centers, including the induced oxidation or sintering of Co0 nanoparticles (48–50). So far, the promoting effect of H2O on the carburization to Co2C has never been reported to the best of our knowledge.

Fig. 5. Facilitating carburization of K-CoO sample with a moderate amount of H2O.

In situ XRD patterns recorded (A) in 10 volume % CO/N2 at 0.8 MPa and (B) in 10 volume % CO + 2 volume % H2O/N2 at 0.1 MPa. Quasi in situ XPS spectra in the near-ambient pressure (NAP) XPS system recorded after reaction at 0.1 MPa (C) in 10 volume % CO/N2 and (D) in 10 volume % CO + 2 volume % H2O/N2.

To obtain more evidence on the catalytic surface, we collected the quasi in situ XPS spectra in the NAP-XPS system during the carburization of K-CoO. As shown in the Co 2p spectra (Fig. 5, C and D), the characteristic peaks at 780.3 and 796.4 eV and their satellite features at 786.3 and 802.9 eV are attributed to the divalent Co species in the octahedral site of CoO (51). In 10% CO/N2, the features of CoO kept almost unchanged, while only a faint signal of Co─C bond was first detected at 300°C, inferring a slight surface carburization of K-CoO (Fig. 5C). However, by co-feeding 2% H2O, the peak of Co─C bond (283.0 eV) initially emerged at 250°C, and then gradually developed with the increasing temperature (Fig. 5D). Meanwhile, the featured Co 2p peaks completely shifted from CoO (780.0 eV) to Co2C (778.1 eV) at 300°C, illustrating the full carburization of the surface. These results explicitly verify the promoting effect of H2O in the carburization of K-CoO. Furthermore, for the fresh K-CoO sample, the K 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 peaks at 295.2 and 292.7 eV are associated with K+ species in K2O (52). With the increasing temperature in CO or CO + H2O flow, these characteristic peaks gradually shifted to high binding energies and lastly reached at 295.7 and 293.0 eV at 300°C, revealing that the surface K2O species reacted with the CO to form carbonate.

To gain insight into this promotion, we contrasted the interaction between CO and pristine CoO surface with and without H2O. As shown in the quasi in situ XPS spectra, the surface CoO (780.2 eV) was fully reduced to Co0 (778.5 eV) at 300°C in 10% CO, while co-feeding 2% H2O prevents this reduction (Fig. 6A). For C 1s spectra (Fig. 6B), a shoulder peak at ~288.0 eV assigned to surface C─O species, including the possible CO32−, HCO3−, and CO2δ−, appears with H2O addition. These adsorbed species were further determined by in situ DRIFTS. The spectra collected at 1 and 30 min are used for probing the initial and final adsorbed species, respectively, while the changing processes are recorded in figs. S25 and S26. As shown in Fig. 6C, for the CoO-t sample in 10% CO, the initial peaks at 1609, 1509, and 1268 cm−1 correspond to b-CO32− adsorbed on the CoO surface and those at 1366 and 1318 cm−1 correspond to polydentate carbonate (p-CO32−) species (40). Along with the surface reduction (fig. S25), some adsorbed species gradually shift to HCO3− (1604 cm−1, H is from surface hydroxyl) and m-CO32− (1463, 1377 cm−1) on Co0. While 2% H2O was added, a band at 1438 cm−1 and the shoulder peak at 1425 cm−1, which are attributed to the stretching vibration of the C═O band and the bending vibration of the C─H band in formyl (HCO*) species, were observed on the CoO surface (53). The b-CO32− and monodentate formate (m-HCOO*, which is identified by the stretching vibrations of the OCO group at 1542 and 1358 cm−1, and the bending vibration of C─H band at 1392 cm−1) were also observed (54). Without K modification, these species mostly convert to adsorbed m-CO32−, which is inactive for carburization. As for the K-CoO sample, a signal at 1745 cm−1 associated with adsorbed CO on three- or fourfold hollow sites (55) was both observed with and without co-feeding H2O, suggesting that the K promoter provides additional sites for enhanced CO adsorption, which is in accordance with the CO-TPD-MS results (fig. S12B). In 10% CO, b-HCOO* at 1565 and 1364 cm−1, and m-CO32− are initially adsorbed and accumulated, while additional HCO3− species (1605 cm−1) was observed at 30 min on the K-CoO surface. Notably, with the addition of 2% H2O, the bands at 1556, 1415, and 1336 cm−1, which are assigned to the CO2δ−, were detected (22, 56, 57). With an extension of the treatment time, these species have accumulated in 1 to 10 min and then are gradually consumed along with the surface carburization (fig. S26). The final adsorbed species on a fully carburized surface is HCOO* while physically adsorbed H2O (1660 cm−1) was also detected. In literature results, compared with HCOO* and CO32−, CO2δ− is easier to split and form C* species for carburization (22). According to the above XPS and infrared (IR) results, we speculate that the promotion originates from the H2O-facilitated formation of surface C─O species, including the HCO* or CO2δ− species. However, without the K promoter, the HCO* converts to CO32−; while only the K promoter and H2O jointly act on the CoO surface, the active CO2δ− species can be generated and involved in the subsequent carburization.

Fig. 6. Effect of co-feeding H2O on structural properties and catalytic performance.

Quasi in situ XPS spectra collected on CoO-t sample after treating in 10 volume % CO with or without co-feeding 2 volume % H2O (A) Co 2p spectra and (B) C 1s spectra. (C) In situ DRIFTS spectra collected at 1 and 30 min on CoO-t and K-CoO samples under different treated conditions. (D) Catalytic stability test with co-feeding 0.5 volume % H2O within 210 hours. Reaction conditions: 300°C, 3.0 MPa, space velocity = 6000 ml g−1 hour−1, H2/CO2 = 3. Quasi in situ XPS spectra of K-Co2C sample that was used in CO2 hydrogenation with co-feeding 0.5 volume % H2O (E) Co 2p spectra and (F) C 1s spectra.

We calculated the dissociation of CO2δ− (CO2*) toward C* species on the CoO (200) surface. As demonstrated in fig. S27, with the presence of K2O promoter and H2O, the CO2* dissociation energy (reaction I: CO2* → CO* + O*) declines about 0.7 to 2.07 eV. Notably, the reaction energies for C* formation of reactions II (CO* → C* + O*) and III (CO* + CO* → C* + CO2*) reduce to 0.67 and −0.54 eV, which are lower than those on clean CoO (6.47 and 3.19 eV) or K2O-CoO (5.45 and 2.47 eV) surfaces. The results show that K2O and H2O jointly promote the dissociation of surface CO2δ− to C* species. Besides, after the dissociation of the C─O species to C*, the adsorption of surface C atoms is important for carburization, and we further investigated this process on CoO. The average number of electrons transferred between C atoms and the CoO surface (described by Bader charge) and the average formation energies of adsorbed C atoms (ΔEform) calculated with and without K2O co-adsorption are summarized in table S7. Two or three C atoms (marked as 2C and 3C) were deposited on the CoO surface to restore the situation of multicarbon co-adsorption. The Bader charges are 2.13 (2C) and 2.16 (3C) on the clean CoO surface. They increase to 2.28 (2C) and 2.22 (3C) in the presence of K2O, indicating that more electrons are transferred from the C atoms to the CoO surface, and that K2O enhances the electronic interaction between C* and the catalyst surface. As a result, with the K2O addition, the ΔEform decreases from 3.69 (2C) and 3.63 eV (3C) to 3.25 (2C) and 3.20 eV (3C), respectively. This reduction in formation energies (exceed, 0.4 eV) demonstrates that the adsorption of C* species on the CoO surface is easier with K2O promotion, which favors C accumulation and permeation to form a bulk carbide. These calculation results agree with the experimental observations that K2O and H2O promote carbide formation.

Given that the surface of K-Co2C decomposes in the reaction (Fig. 2F), there is a possibility to exploit the beneficial effect of co-feeding H2O for inhibiting this decomposition and improving the catalytic stability. We first evaluated the effect of co-fed H2O content on the performance (fig. S28; the data are collected at TOS = 3 hours, while there is no obvious deactivation) and found that when it increases to 0.25 and 0.5%, the CO2 conversion slightly decreases from 37.9 to 35.6% and 35.3%, respectively. However, more H2O addition exacerbates the activity declination, while the conversion drops to 24.2% with co-feeding 2.5% H2O. While the added H2O content was increased to 25%, the overall CO2 conversion further dropped to 17.5% and the CH4 (selectivity as 86.8%) dominates in the products. The generated H2O in the actual reaction or its extra addition gives rise to the competitive adsorption with other reactants or intermediates and increases the rate of reverse reaction, which jointly causes a gradually reduced CO2 conversion (28). Moreover, a volcanic curve was observed for C2+ HCs selectivity and yield with H2O content, and at the optimum content of 0.5%, the C2+ HCs selectivity increases to 53.1% and its STY of C2+ HCs is 8.0 mmol g−1 hour−1. As can be seen from the C2+ HCs composition (fig. S29), co-feeding 0.5% H2O leads to a more centralized product distribution (α decreases from 0.53 to 0.48) and an enhanced generation of light olefins (the C2 ~ C4= selectivity increases to 19.9% and O/P ratio increases to 1.0), indicating that co-feeding 0.5% H2O here protects the surface Co2C from decomposition. Moreover, in CO-FTS, H2O sometimes promotes the formation of CHx* species via an H2O-assisted methylidyne mechanism and increases the C5+ selectivity (58). However, a slightly decreasing C5+ selectivity was observed with H2O addition here. It is speculated that the low concentration of H2O (0.5% ~ 2.5%) does not substantially influence the reaction pathway but is enough to modulate the surface compositions. The promoting effect of H2O on stabilizing the structure of Co2C and its catalytic features is expected to enable its practical application in the CO2 hydrogenation reaction with high temperature and pressure.

The catalytic stability of K-Co2C in CO2 hydrogenation was examined, as shown in figs. S30 and S31, we found that the H2O content has an impact on the catalyst deactivation. Within the initial 35 hours, without co-feeding H2O, the CO2 conversion and C2+ HCs selectivity decreased from 38.2 to 31.6% and 46.5 to 38.8%, respectively. The addition of H2O effectively inhibited this activity decline, and when co-feeding 0.5% or more H2O, the catalytic performance basically kept stable in the initial 35 hours. We further compared the changes in catalytic performance with various H2O contents (fig. S32). The drops of C2+ HCs STY can be clearly observed when the H2O content is 0 or 0.25%. As for the H2O content of 0.5 ~ 2.5%, the ratios of CO2 conversion collected at 3 and 35 hours (ratio A) and those of C2+ HCs STY (ratio B) are all in the range of 96 to 98%, which are higher than those recorded at 0 or 0.25% H2O. It reveals that co-feeding H2O is beneficial to mitigating the deactivation, and when the H2O content exceeded 0.5%, the features of deactivation are quite similar. Furthermore, without co-feeding H2O, the decrease of the activity (31.6 to 24.2%) and selectivity alterations were clearly observed in 35 to 50 hours, while final CH4 selectivity increased to 74.7% and the STY of C2+ HCs dropped from 7.6 to 2.6 mmol g−1 hour−1 within 50 hours on stream (fig. S33). By comparison, with co-feeding 0.5% H2O (Fig. 6D), the K-Co2C catalyst showed higher stability throughout a 210-hour test. The final selectivity to C2+ HCs remained at 49.2%, exceeding 90% of the initial values (53.0%, at 15 hours), and the STY of C2+ HCs still retained 7.2 mmol g−1 hour−1 at 210 hours. The XRD patterns of spent samples (fig. S34) show that co-feeding 25% H2O caused the complete decomposition of Co2C, which is in accordance with the in situ XRD results (Fig. 4E). However, no substantial difference was observed in spent samples with co-feeding 0.5 or 2.5% H2O, indicating that their evolution mainly occurs on the catalytic surface. The quasi in situ XPS spectra of the spent K-Co2C with 0.5% H2O are shown in Fig. 6 (E and F). The binding energies of Co 2p1/2 and Co2p3/2 at 793.5 and 778.3 eV reveal that the catalytic surface is Co2C. Notably, the addition of 0.5% H2O enhances the signal of the Co─C bond at 283.1 eV (C 1s spectra) in comparison to the results of the K-Co2C sample which was used without co-feeding H2O (Fig. 2F). The estimated surface C/Co ratio increased from 0.27 (without H2O) to 0.46 with co-feeding 0.5% H2O, particularly substantiating that the decomposition of Co2C has been inhibited by adding moderate H2O in the reaction.

In conclusion, we provide an in situ synthesized and stable K-Co2C catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation which shows outstanding activity and selectivity to C2+ HCs up to 67.3% at 300°C, 3.0 MPa. Compared with metallic cobalt catalysts, K-Co2C is more competitive in accelerating the formation of C2+ HCs, and a C-rich and H-lean surface environment suppresses the side reaction toward CH4. This K-Co2C catalyst is promising to be combined with the zeolites or membrane reactors to further optimize the product composition and alleviate the downstream separation needs for improving its practical applications (3, 59). Adsorbed CO derived from carbonate splitting is an important intermediate for coupling to C2+ HCs as confirmed by in situ DRIFTS. Multispectral studies, including in situ XRD, quasi in situ XPS, and DFT calculations, reveal that Co2C is directly generated from CoO instead of undergoing the reduction to Co0. The reactants (H2 and CO2) or the product (H2O) of high concentrations all can cause the decomposition of Co2C to Co0, while the delicate balance of the reaction atmosphere and the K promoter plays vital roles in the stabilization of Co2C. Co-feeding a small amount of H2O instead facilitates the carburization and stabilization of Co2C. During the carburization, 2% H2O and the K promoter jointly act on the CoO surface and stimulate the formation of key CO2δ− species, followed by its dissociation to active C* species. The K promoter also enables the subsequent C* adsorption on the CoO surface, favoring the C accumulation and permeation. Inspired by this finding, 0.5% H2O was co-fed in the feed gas to stabilize the surface structure of K-Co2C and it markedly prolongs the catalytic stability from 35 to over 200 hours. Given that H2O is an inevitable impurity in the flue gas (a key source for CO2 capture) and generally considered a poison in CO2 hydrogenation reaction, our study highlights the unique promoting effect of H2O in feed gas on Co2C catalyst and it is expected to improve its practical application in CO2 conversion. However, considering that the excessive H2O addition is conversely detrimental to Co2C, its separation before the catalytic conversion or the surface hydrophobic or hydrophilic modifications to control its content within the ideal range is still needed. The fundamental understanding of the formation and stabilization of Co2C also provides opportunities for its potential application in other reactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Catalyst preparation

Synthesis of Co3O4 and modified Co3O4 precursor

Co(NO3)2·6H2O was purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Citric acid, Na2CO3, K2CO3, and Cs2CO3 were purchased from Bodi Chemical Trade Co., Ltd. Co3O4 precursor was prepared using a citric acid–induced sol-gel method. Typically, citric acid and Co(NO3)2·6H2O (molar ratio = 13/20) were dissolved in ethanol and the mixed solution was aged at 30°C for hydrolysis and complexation. Then, the ethanol was fully evaporated at 80°C. The obtained foamy gel was dried at 80°C for 12 hours and further calcined in air at 450°C for 4 hours to get the Co3O4 precursor.

Alkali metal–modified Co3O4 precursors were synthesized by an IWI method using an aqueous solution of their carbonates. The molar amount of Na2CO3 or Cs2CO3 was fixed as 0.025 mmol, whereas that of K2CO3 was tried as 0.013, 0.025, and 0.050 mmol (the corresponding mass fractions of K are 0.49, 0.98, and 1.96%). As an example, 0.0035 g (0.025 mmol) of K2CO3 was dissolved in 0.12 g of H2O through sonication, and then the solution was dropped on 0.2 g of Co3O4 under stirring at room temperature. The resulting power was dried at 80°C for 12 hours and calcined in air at 400°C for 2 hours to get the 0.98% K-Co3O4 precursor.

Synthesis of testing samples

We used the in situ XRD reactor chamber to prepare the samples which were denoted as K-CoO, K-Co0, CoO-t, and Co2C-t, respectively. The K-CoO sample was prepared from the reduction of 0.98% K-Co3O4 in H2 at 240°C, 0.8 MPa. The K-Co0 sample was obtained from the decomposition of K-Co2C in H2 at 340°C, 0.8 MPa. The CoO-t sample was prepared from the reduction of Co3O4 precursor in H2 at 220°C, 0.1 MPa. The Co2C-t sample was prepared from two-step treatments from Co3O4 precursor, including the initial reduction at 260°C, and the following carburization in CO, as recorded in fig. S23A. Before the ex situ structural characterizations, the Co0-t and K-Co2C samples were carefully passivated in the flow of 1% O2/N2 (20 ml min−1) at ~20°C for 1 hour and then were transferred to the glove box for preservation.

Catalyst characterization

XRD patterns were recorded on a Rigaku SmartLab 9-kW diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) and with a scanning rate of 8°/min. In situ XRD measurements were performed in an XRK 900 reactor chamber and the heating process was controlled by a TCU 750 temperature control unit. The patterns were collected for each 10 min until the structure is stable for at least 1 hour at the given conditions. As for the structural evolution in CO2 hydrogenation, the sample was directly heated to the target temperature in the reactive gas at 0.8 MPa. For the structural evolution in other atmospheres (H2/CO2/CO/H2O), the specific conditions were introduced in the corresponding results.

Quasi in situ XPS was performed on a spectrometer equipped with an Al K x-ray source at 300 W. Before the test, the samples, including the K-Co2C and Co0-t (without the passivation), were carefully transferred from the glove box to the XPS analysis chamber without the exposure to air. Besides, the carburization processes for CoO-t and K-CoO samples were simulated in 10% CO/N2 or 10% CO + 2% H2O/N2 in the reaction chamber equipped with the NAP-XPS system. Here, these quasi in situ XPS spectra were recorded after reaching the setting temperatures for 20 min. The thermal couples were placed at the side of the powder sample for in situ XRD (set temperature, ±30°C) and on the upper surface of the sample piece for quasi in stu XPS, respectively (fig. S35).

In situ DRIFTS experiments were performed using the Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 spectrometer with a mercury cadmium telluride detector, and the background spectrum was collected after N2 purge for at least 1 hour. The flow rate of reactive gas (CO2/H2/N2 = 21:63:16) or N2 is 30 ml min−1, whereas that of CO2, CO, or H2 is 10 ml min−1. As for mechanism studies on K-Co2C and Co0-t samples, the testing temperature is not above 260°C for avoiding the destroy from CO2 or H2 on catalyst structure. As shown in fig. S36, these samples were in situ synthesized in the IR cell at 300°C, 1.2 MPa for 3 hours, and then was purged (300°C) and cooled (50°C) in N2, atmospheric pressure before the adsorption of CO2 and the following switching to H2. The co-fed H2O at atmospheric pressure for in situ XRD or DRIFTS and quasi in situ XPS test is stored in a glass wash bottle, which is placed before the reactor chamber. Its content is dependent on the controlled temperature of wash bottle. The theoretical H2O content was calculated according to the following equation and was used for the expression. The actual H2O content was determined using the NaOH and silica gel as the absorbents (fig. S37), while the above results are listed in table S8.

TPD tests were carried out on a Quantachrome ChemBET Pulsar analyzer, while the desorbed species was detected by the Pfeiffer GSD-350 online MS. Typically, the samples were loaded into a quartz tube and flushed with N2 at 300°C for 1 hour to remove undesired adsorbates, and then cooled to room temperature. The samples were first retreated in the reactive gas at 300°C for 1 hour to remove the external passivation layer, and then flushed with N2 for 1 hour. These samples were cooled to 30°C to adsorb CO2 or CO in 1 hour, followed by switching to N2 to purge for 30 min. Then, the desorption and analysis program were conducted with a heating rate of 10°C min−1 to 700°C.

TEM and HRTEM images were obtained on a Tecnai F30 HRTEM instrument (FEI Corp) with a voltage of 300 kV. EDS elemental mapping images were obtained on a JEM ARM200F thermal-field emission microscope equipped with a probe spherical aberration (Cs) corrector with a voltage of 200 kV. UV Raman spectra were collected on a homemade triple-stage UV Raman spectrometer with a resolution of 2 cm−1. The wavelength of UV laser line from a double-frequency 514-nm laser was set at 320 nm. The textural properties were determined by Ar absorption-desorption on a Quantachrome AUTO-SORB-1-MP sorption at 87 K. The surface area was calculated using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method. The concentrations of alkali metals and Co were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry on a PerkinElmer AVIO 500 instrument and the results are listed in table S9. TGA was conducted on a TGA-SDTA851e thermobalance in the air flow (25 ml min−1) with a heating rate of 5°C min−1 from 50° to 800°C.

Catalytic activity test

The CO2 hydrogenation was conducted in a stainless steel fixed-bed flow reactor with an 8-mm inner diameter. A total of 150 mg of Co3O4 or alkali metal–modified Co3O4 precursor (20 to 40 meshes) was diluted with 450 mg of quartz sand (20 to 40 meshes), and then loaded into the middle of the reactor. Catalytic performance was tested in the reactive gas (CO2/H2/Ar = 1:3:1.5, space velocity = 6000 ml g−1 hour−1, P = 3.0 MPa unless otherwise noted) at 260°, 300°, and 340°C. The products were collected at about 3 hours after reaching the steady state on steam. As shown in fig. S38, all the products, including the liquid oxygenates and C5+ HCs, were heated by an oven and heating belt at 100°C for full vaporization and accessed into the online chromatography (Agilent, 7890B) for the analysis by the thermal conductivity detector and flame ionization detector, while the Ar was used as an internal standard. CO2 conversion and CO selectivity were calculated on a carbon-atom basis according to the following equations

where nCO2,in and nCO2,out represent the concertation of CO2 at the inlet and outlet. nCO,out represents the CO concertation at the outlet. The total selectivity of alcohols and dimethyl ether is below 1.5% and therefore was not reported here.

The selectivity to HC CnHm was calculated for representing the HCs distribution

where CnHm,out represents moles of detected individual HCs product.

The STY, the O/P ratio, and the chain growth factor α were calculated as shown below

where STYa and STYb represent the STY values normalized based on catalyst mass and surface area (SBET; table S4). Wn and n represent the mass fraction and the carbon number of HCs products. The carbon balance was in the range of 95 to 105%.

The contents (0.25 to 25%) of H2O mentioned in this work represent those of extra-added H2O in the carburization gas or feed gas. The H2O was added using a steel gas wash bottle, which can be pressurized to 3.0 MPa, and the setting temperatures are listed in table S8. For the kinetics tests (activation energy and reaction order), the conversion was decreased below 10% by varying the space velocity.

Theory computational methods

The basic thermodynamic calculations (ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS) were carried out by the Aspen Plus V11 software. All spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed with the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package. The exchange-correlation energies were calculated by the generalized gradient approximation approach with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional (60). Core electrons were frozen and treated with the projector-augmented wave theory (61). Valence electrons were taken as Co (4s23d7), C (2s22p2), and O (2s22p4). The plane-wave basis set was truncated at 500 eV for gas molecules and surface calculations and was increased to 650 eV for bulk crystals to mitigate the effect from Pulay stress. Gaussian smearing with 0.1-eV width was applied to oxides and molecules while first order of Methfessel-Paxton smearing was applied to metal and carbides (62). Brillouin zones were treated with the Monkhorst-Pack k-points mesh (63). The k-points, lattice parameters, space groups, and magnetics are summarized in table S10. The van der Waals interaction correction was applied for all calculations with the DFT-D3 method (64). The climbing image nudged elastic band method was used to find transition states, combined with the dimer method. It was verified that each transition state had only one imaginary vibrational frequency along the reaction coordinate direction. A three-layer slab model was built for the CoO (200) surface and the bottom two layers were fixed during structural optimization. The criteria of force convergence for surface calculations were set to 0.03 eV/Å on all atoms. The Hubbard U-correction was applied to oxides for localized d-state electrons (65). A value of 3.3 eV for Co was taken from the work of Wang et al. (66). Bader charge analysis was performed to investigate the charge transfer of the adsorbate-surface system (67). The adsorption and activation of CO2 and H2 were investigated on Co2C (101) and (020) surfaces, and the Co (002) surface. All surface calculations were performed in the Monkhorst-Pack scheme using k-points of 2 × 2 × 1 with the addition of a vacuum layer of 15 Å to avoid interactions between repeating periodic elements. In the structural optimization of Co2C surfaces, the bottom 1/3 Co and C atoms are fixed in their original atomic positions, while the remaining top 2/3 Co and C atoms together with the adsorbate are completely relaxed. We constructed three kinds of CoO (200) surfaces: clean surface, surface containing only K2O, and surface containing both K2O and H2O, and calculated the reaction energy of the stepwise decomposition of CO2δ− to C* species on these three surfaces. The optimized structures involved are displayed in figs. S39 and S40, respectively.

Ab initio thermodynamics (68) was applied to construct the bulk phase diagram, locate the reaction conditions on the resulting phase diagram, and calculate formation energies. The explanation pertaining to the equilibrium assumptions inherent to this thermodynamics method is shown in the Supplementary Materials. In the bulk phase diagram, the phase with lowest formation energy is identified as the stable phase. The chemical potentials of C and O are determined by the free energies of the gas species with the assumption that the gas phase is equilibrated with the catalysts. The free energy of a molecule is calculated according to the following equations

where GCO2 and GCO are the free energy of CO2 and CO. Ggas is the free energy of the gas molecule, is the DFT energy of the gas molecule, ZPEgas is the zero-point vibrational energy of the gas molecule, is the enthalpy change of the gas molecule from 0 to 533.15 K, T is set as 533.15 K according to the initial carburization temperature for K-Co3O4 sample, and is the entropy of the gas molecule at 533.15 K, R is the gas constant, pgas is the partial pressure of the gas, and pref is the reference pressure, which is set to 1 bar. The following temperature and partial pressures were used in determining the chemical potential of O and C in Fig. 4B: red dot (533.15 K, 1.45 bar CO2, 1 × 10−10 bar CO), black dot (533.15 K, 1.45 bar CO2, 1.645 × 10−3 CO). The pressure of CO was set to 1 × 10−10 bar to represent that it does not exist in the initial reaction condition, while all other partial pressures were measured from our experiments.

The average formation energy ∆Eform of each C atom adsorption on the CoO (200) surface with or without the co-adsorption of K2O is defined with the following equation

where Etotal is the total DFT energy of a surface adsorption structure with z C atoms, Esur is the DFT energy of the clean CoO surface (either with or without co-adsorbed K2O). z is set as 2 and 3, while is set as −8.16 eV on the basis of the above calculation result of the chemical potential of carbon.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the State Key Laboratory of Catalysis, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing the quasi in situ XPS test. We also thank W. Liu at Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences and C. Shi at Dalian University of Technology for helping on EDS and TPD-MS characterization.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22172013 and 22288201), The Major Science and Technology Special Project of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022A01002-1), The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DUT22LK24, DUT22QN207, and DUT22LAB602), The Liaoning Revitalization Talent Program (XLYC2008032), The CUHK Research Startup Fund (no. 4930981), The Donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (PRF #59759-DNI6), and Tingzhou Youth Program (2021QN08).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: M.W., G.Z., T.P.S., C.S., and X.G. Methodology: M.W., P.W., M.Z., R.L., and J.Z. Investigation: M.W., P.W., M.Z., R.L., and Yi Liu. Visualization: M.W., Z.C., Yulong Liu, K.B., and F.D. Supervision: G.Z., T.P.S., X.N., Q.F., C.S., and X.G. Writing—original draft: M.W., P.W., R.L., J.W., J.Z., and G.Z. Writing—review and editing: G.Z., T.P.S., X.N., Q.F., C.S., and X.G.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S40

Tables S1 to S10

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Falkowski P., Scholes R. J., Boyle E., Canadell J., Canfield D., Elser J., Gruber N., Hibbard K., Högberg P., Linder S., Mackenzie F. T., Moore B. III, Pedersen T., Rosenthal Y., Seitzinger S., Smetacek V., Steffen W., The global carbon cycle: A test of our knowledge of earth as a system. Science 290, 291–296 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao B., Sun M., Chen F., Shi Y., Yu Y., Li X., Zhang B., Unveiling the activity origin of iron nitride as catalytic material for efficient hydrogenation of CO2 to C2+ hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 4496–4500 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei J., Yao R., Han Y., Ge Q., Sun J., Towards the development of the emerging process of CO2 heterogenous hydrogenation into high-value unsaturated heavy hydrocarbons. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 10764–10805 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan L., Xia C., Yang F., Wang J., Wang H., Lu Y., Strategies in catalysts and electrolyzer design for electrochemical CO2 reduction toward C2+ products. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay3111 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye R. P., Ding J., Gong W., Argyle M. D., Zhong Q., Wang Y., Russell C. K., Xu Z., Russell A. G., Li Q., Fan M., Yao Y. G., CO2 hydrogenation to high-value products via heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 5698 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou W., Cheng K., Kang J., Zhou C., Subramanian V., Zhang Q., Wang Y., New horizon in C1 chemistry: Breaking the selectivity limitation in transformation of syngas and hydrogenation of CO2 into hydrocarbon chemicals and fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3193–3228 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvis H. M. T., Bitter J. H., Khare C. B., Ruitenbeek M., Dugulan A. I., de Jong K. P., Supported iron nanoparticles as catalysts for sustainable production of lower olefins. Science 335, 835–838 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Y., Li X., Gao J., Wang J., Ma G., Wen X., Yang Y., Li Y., Ding M., A hydrophobic FeMn@Si catalyst increases olefins from syngas by suppressing C1 by-products. Science 371, 610–613 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han Y., Fang C., Ji X., Wei J., Ge Q., Sun J., Interfacing with carbonaceous potassium promoters boosts catalytic CO2 hydrogenation of iron. ACS Catal. 10, 12098–12108 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin T., Yu F., An Y., Qin T., Li L., Gong K., Zhong L., Sun Y., Cobalt carbide nanocatalysts for efficient syngas conversion to value-added chemicals with high selectivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 1961–1971 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong L., Yu F., An Y., Zhao Y., Sun Y., Li Z., Lin T., Lin Y., Qi X., Dai Y., Gu L., Hu J., Jin S., Shen Q., Wang H., Cobalt carbide nanoprisms for direct production of lower olefins from syngas. Nature 538, 84–87 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z., Zhong L., Yu F., An Y., Dai Y., Yang Y., Lin T., Li S., Wang H., Gao P., Sun Y., He M., Effects of sodium on the catalytic performance of comn catalysts for Fischer-Tropsch to olefin reactions. ACS Catal. 7, 3622–3631 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C., Li S., Zhong L., Sun Y., Theoretical insights into morphologies of alkali-promoted cobalt carbide catalysts for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. J. Phy. Chem. C 125, 6061–6072 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z., Lin T., Yu F., An Y., Dai Y., Li S., Zhong L., Wang H., Gao P., Sun Y., He M., Mechanism of the Mn promoter via CoMn spinel for morphology control: Formation of Co2C nanoprisms for Fischer-Tropsch to olefins reaction. ACS Catal. 7, 8023–8032 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z., Yu D., Yang L., Cen J., Xiao K., Yao N., Li X., Formation mechanism of the Co2C nanoprisms studied with the CoCe system in the Fischer-Tropsch to olefin reaction. ACS Catal. 11, 2746–2753 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang R., Xia Z., Zhao Z., Sun F., Du X., Yu H., Gu S., Zhong L., Zhao J., Ding Y., Jiang Z., Characterization of CoMn catalyst by in situ x-ray absorption spectroscopy and wavelet analysis for Fischer-Tropsch to olefins reaction. J. Energy Chem. 32, 118–123 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moya-Cancino J. G., Honkanen A.-P., van der Eerden A. M. J., Oord R., Monai M., ten Have I., Sahle C. J., Meirer F., Weckhuysen B. M., de Groot F. M. F., Huotari S., In situ x-ray raman scattering spectroscopy of the formation of cobalt carbides in a Co/TiO2 Fischer-Tropsch synthesis catalyst. ACS Catal. 11, 809–819 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin T., Gong K., Wang C., An Y., Wang X., Qi X., Li S., Lu Y., Zhong L., Sun Y., Fischer-Tropsch synthesis to olefins: Catalytic performance and structure evolution of Co2C-based catalysts under a CO2 environment. ACS Catal. 9, 9554–9567 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan T., Liu H., Shao S., Gong Y., Li G., Tang Z., Cobalt catalysts enable selective hydrogenation of CO2 toward diverse products: Recent progress and perspective. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 10486–10496 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gnanamani M. K., Jacobs G., Keogh R. A., Shafer W. D., Sparks D. E., Hopps S. D., Thomas G. A., Davis B. H., Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: Effect of pretreatment conditions of cobalt on activity and selectivity for hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Appl. Catal. A 499, 39–46 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang S., Liu X., Shao Z., Wang H., Sun Y., Direct CO2 hydrogenation to ethanol over supported Co2C catalysts: Studies on support effects and mechanism. J. Catal. 382, 86–96 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S., Liu X., Luo H., Wu Z., Wei B., Shao Z., Huang C., Hua K., Xia L., Li J., Liu L., Ding W., Wang H., Sun Y., Morphological modulation of Co2C by surface-adsorbed species for highly effective low-temperature CO2 reduction. ACS Catal. 12, 8544–8557 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Z., Tao Y., Wu J., Zhang C., He H., Long L., Lee Y., Li T., Zhang Y. B., Robust metal-triazolate frameworks for CO2 capture from flue gas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2750–2754 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J., Wang P., Zhang X., Zhang G., Li R., Li W., Senftle T. P., Liu W., Wang J., Wang Y., Zhang A., Fu Q., Song C., Guo X., Dynamic structural evolution of iron catalysts involving competitive oxidation and carburization during CO2 hydrogenation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm3629 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bezemer G. L., Remans T. J., Bavel A. P. v., Dugulan A. I., Direct evidence of water-assisted sintering of cobalt on carbon nanofiber catalysts during simulated Fischer-Tropsch conditions revealed with in situ Mössbauer spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8540–8541 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsakoumis N. E., Walmsley J. C., Ronning M., van Beek W., Rytter E., Holmen A., Evaluation of reoxidation thresholds for γ-Al2O3-supported cobalt catalysts under Fischer-Tropsch synthesis conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3706–3715 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf M., Gibson E. K., Olivier E. J., Neethling J. H., Catlow C. R. A., Fischer N., Claeys M., Water-induced formation of cobalt-support compounds under simulated high conversion Fischer-Tropsch environment. ACS Catal. 9, 4902–4918 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang W., Wang C., Liu Z., Wang L., Liu L., Li H., Xu S., Zheng A., Qin X., Liu L., Xiao F.-S., Physical mixing of a catalyst and a hydrophobic polymer promotes CO hydrogenation through dehydration. Science 377, 406–410 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An Y., Lin T., Yu F., Wang X., Lu Y., Zhong L., Wang H., Sun Y., Effect of reaction pressures on structure–performance of Co2C-based catalyst for syngas conversion. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 15647–15653 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu M., Cao C., Xu J., Understanding kinetically interplaying reverse water-gas shift and Fischer-Tropsch synthesis during CO2 hydrogenation over Fe-based catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 641, 118682 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z., Lu W., Yang R., Zhu H., Dong W., Sun F., Jiang Z., Lyu Y., Liu T., Du H., Ding Y., Insight into the formation of Co@Co2C catalysts for direct synthesis of higher alcohols and olefins from syngas. ACS Catal. 8, 228–241 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang R., Wen G., Adidharma H., Russell A. G., Wang B., Radosz M., Fan M., C2 oxygenate synthesis via Fischer-Tropsch synthesis on Co2C and Co/Co2C interface catalysts: How to control the catalyst crystal facet for optimal selectivity. ACS Catal. 7, 8285–8295 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Li G., Li Z., Tang C., Feng Z., An H., Liu H., Liu T., Li C., A highly selective and stable ZnO-ZrO2 solid solution catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701290 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paalanen P. P., van Vreeswijk S. H., Weckhuysen B. M., Combined in situ x-ray powder diffractometry/raman spectroscopy of iron carbide and carbon species evolution in Fe(−Na–S)/α-Al2O3 catalysts during Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. ACS Catal. 10, 9837–9855 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selvakumar S., Nuns N., Trentesaux M., Batra V. S., Giraudon J. M., Lamonier J. F., Reaction of formaldehyde over birnessite catalyst: A combined XPS and ToF-SIMS study. Appl Catal B 223, 192–200 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin T., Liu P., Gong K., An Y., Yu F., Wang X., Zhong L., Sun Y., Designing silica-coated CoMn-based catalyst for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis to olefins with low CO2 emission. Appl Catal B 299, 120683 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Y., Long R., Xiong Y., Regulating C-C coupling in thermocatalytic and electrocatalytic COx conversion based on surface science. Chem. Sci. 10, 7310–7326 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jo H., Khan M. K., Irshad M., Arshad M. W., Kim S. K., Kim J., Unraveling the role of cobalt in the direct conversion of CO2 to high-yield liquid fuels and lube base oil. Appl Catal B 305, 121041 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X., Zeng C., Gong N., Zhang T., Wu Y., Zhang J., Song F., Yang G., Tan Y., Effective suppression of CO selectivity for CO2 hydrogenation to high-quality gasoline. ACS Catal. 11, 1528–1547 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei M., Hong B., Yan L., Chen R., Huang F., Zheng Y., Enhanced stability for preferential oxidation of CO in H2 under H2O and CO2 atmosphere through interaction between iridium and copper species. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 47, 24374–24387 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukashuk L., Yigit N., Rameshan R., Kolar E., Teschner D., Havecker M., Knop-Gericke A., Schlogl R., Fottinger K., Rupprechter G., Operando insights into CO oxidation on cobalt oxide catalysts by NAP-XPS, FTIR, and XRD. ACS Catal. 8, 8630–8641 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu J., Su Y., Chai J., Muravev V., Kosinov N., Hensen E. J. M., Mechanism and nature of active sites for methanol synthesis from CO/CO2 on Cu/CeO2. ACS Catal. 10, 11532–11544 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lv Y., Wang P., Liu D., Zhang F., Senftle T. P., Zhang G., Zhang Z., Huang J., Liu W., Tracing the active phase and dynamics for carbon nanofiber growth on nickel catalyst using environmental transmission electron microscopy. Small methods 6, 2200235 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Smit E., Weckhuysen B. M., The renaissance of iron-based Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: On the multifaceted catalyst deactivation behaviour. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 2758–2781 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Smit E., Cinquini F., Beale A. M., Safonova O. V., van Beek W., Sautet P., Weckhuysen B. M., Stability and reactivity of ε-χ-θ iron carbide catalyst phases in Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: Controlling μC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14928–14941 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf M., Fischer N., Claeys M., Formation of metal-support compounds in cobalt-based Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: A review. Chem Catal. 1, 1014–1041 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li W., Nie X., Yang H., Wang X., Polo-Garzon F., Wu Z., Zhu J., Wang J., Liu Y., Shi C., Song C., Guo X., Crystallographic dependence of CO2 hydrogenation pathways over HCP-Co and FCC-Co catalysts. Appl Catal B 315, 121529 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Koppen L. M., Iulian Dugulan A., Leendert Bezemer G., Hensen E. J. M., Sintering and carbidization under simulated high conversion on a cobalt-based Fischer-Tropsch catalyst; manganese oxide as a structural promotor. J. Catal. 413, 106–118 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf M., Mutuma B. K., Coville N. J., Fischer N., Claeys M., Role of CO in the water-induced formation of cobalt oxide in a high conversion Fischer-Tropsch environment. ACS Catal. 8, 3985–3989 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claeys M., Dry M. E., van Steen E., van Berge P. J., Booyens S., Crous R., van Helden P., Labuschagne J., Moodley D. J., Saib A. M., Impact of process conditions on the sintering behavior of an alumina-supported cobalt Fischer-Tropsch catalyst studied with an in situ magnetometer. ACS Catal. 5, 841–852 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen L., Tao F. F., Tang Y., Dou J., Bao X. J., Understanding catalyst surfaces during catalysis through near ambient pressure x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 119, 6822–6905 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen L., Ren S., Xing X., Yang J., Li X., Wang M., Chen Z., Liu Q., Poisoning mechanism of KCl, K2O and SO2 on Mn-Ce/CuX catalyst for low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 167, 609–619 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romero-Sarria F., Bobadilla L. F., Jiménez Barrera E. M., Odriozola J. A., Experimental evidence of HCO species as intermediate in the fischer tropsch reaction using operando techniques. Appl Catal B 272, 119032 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bobadilla L. F., Santos J. L., Ivanova S., Odriozola J. A., Urakawa A., Unravelling the role of oxygen vacancies in the mechanism of the reverse water–gas-shift reaction by operando DRIFTS and UV–Vis spectroscopy. ACS Catal. 8, 7455–7467 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu R., Leshchev D., Stavitski E., Juneau M., Agwara J. N., Porosoff M. D., Selective hydrogenation of CO2 and CO over potassium promoted Co/ZSM-5. Appl Catal B 284, 119787 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonugunta P., Dugulan A. I., Bezemer G. L., Brück E., Role of surface carboxylate deposition on the deactivation of cobalt on titania Fischer-Tropsch catalysts. Catal. Today 369, 144–149 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Falbo L., Visconti C. G., Lietti L., Szanyi J., The effect of CO on CO2 methanation over Ru/Al2O3 catalysts: A combined steady-state reactivity and transient DRIFT spectroscopy study. Appl Catal B 256, 117791 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rytter E., Holmen A., Perspectives on the effect of water in cobalt Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. ACS Catal. 7, 5321–5328 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H., Qiu C., Ren S., Dong Q., Zhang S., Zhou F., Liang X., Wang J., Li S., Yu M., Na+-gated water-conducting nanochannels for boosting CO2 conversion to liquid fuels. Science 367, 667–671 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kresse G., Furthmiiller J., Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blochl P. E., Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Methfessel M., Paxton A. T., High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Monkhorst H. J., Pack J. D., Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H., A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dudarev S. L., Botton G. A., Savrasov S. Y., Humphreys C. J., Sutton A. P., Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang L., Maxisch T., Ceder G., Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+U framework. Phys. Rev. B 73, 195107 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Henkelman G., Arnaldsson A., Jónsson H., A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 68.S. Blomberg, H. Bluhm, J. A. v. Bokhoven, M. Bracconi, A. Cuoci, J. Frenken, I. Groot, J. Gustafson, U. Hartfelder, O. Karslıoğlu, P. J. Kooyman, E. Lundgren, M. Maestri, M. Nachtegaal, S. Rebughini, K. Reuter, A. Stierle, J. Zetterberg, J. Zhou, Operando Research in Heterogeneous Catalysis. A. W. Castleman, J. P. Toennies, K. Yamanouchi, W. Zinth, Eds., (Springer International Publishing, 2017), vol. 114. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S40

Tables S1 to S10