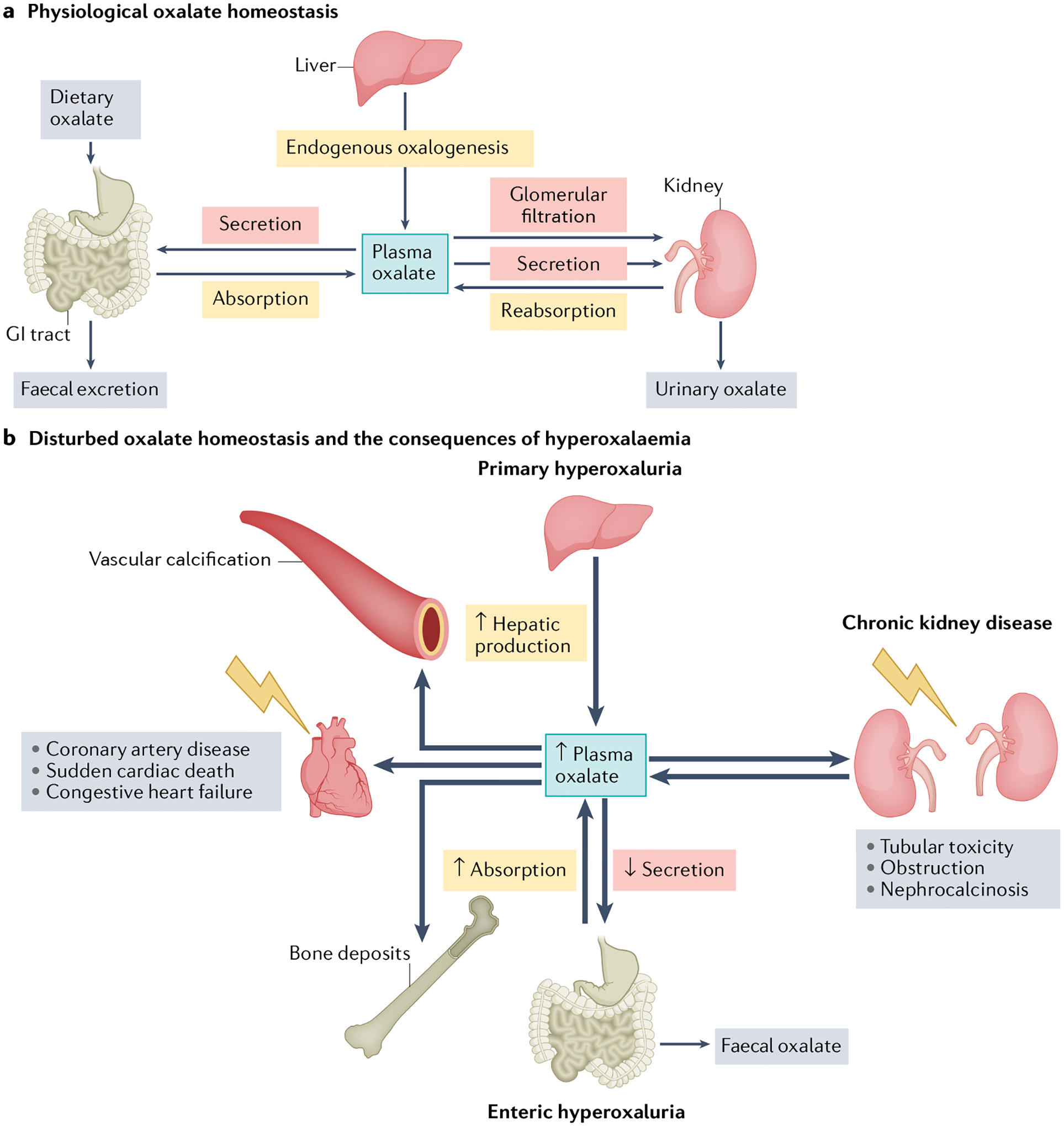

Fig. 1 |. Oxalate homeostasis.

a, Physiological oxalate homeostasis. Oxalate homeostasis is maintained by a delicate interplay of supply (that is, hepatic production, gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of dietary oxalate and tubular reabsorption of circulating oxalate) and excretion (GI secretion and faecal oxalate, glomerular filtration, tubular secretion and urinary oxalate). Physiological plasma oxalate concentrations of 1–5 μM have no known negative effects on the cardiovascular system. b, Disturbed oxalate homeostasis and the consequences of hyperoxalaemia. Oxalate homeostasis might be disturbed by alterations in numerous pathways. Plasma oxalate concentrations can increase owing to decreased urinary excretion in chronic kidney disease, increased hepatic production in primary hyperoxaluria or increased GI absorption in enteric hyperoxaluria. When kidney function is still sufficiently high to enable compensatory oxalate excretion in the kidney, hyperoxaluria can result in nephrocalcinosis, tubular toxicity and obstruction. Loss of kidney excretory function can lead to supersaturation of plasma with oxalate, which can have severe adverse effects on the cardiovascular system. High plasma oxalate is associated with sudden cardiac death, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure and vascular calcification. Oxalate can also deposit in other tissues such as bone, thyroid, spleen and lungs.