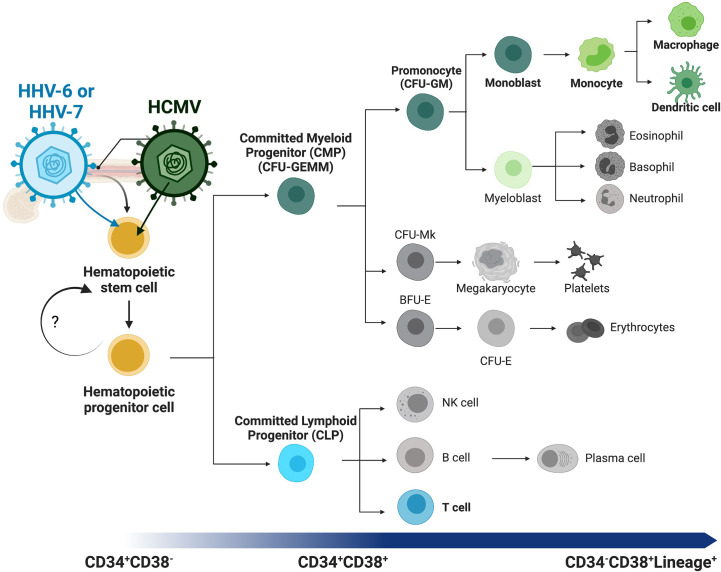

Figure 1.

Overview of human hematopoiesis. Schematic overview of human hematopoiesis from early hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to more mature hematopoietic progenitors (HPCs), both populations with self-renewal and multilineage differentiation potential. The heterogeneous HPC population subsequently gives rise to a series of intermediate progenitors, including commitment to either the lymphoid or myeloid lineages through the committed lymphoid (CLP) or committed myeloid progenitor (CMP), respectively. Lineage analysis and differentiation capability of the CMP population and direct descendants can be assessed with the classic colony forming unit (CFU) assay, and populations distinguished by morphology and other characteristics. Lineage commitment of the monocytic lineage begins with the CFU-GM (CFU-granulocyte/macrophage) diverging from the CFU-Mk (CFU-megakaryocyte) and erythroid [BFU-E (burst-forming unit-erythroid) and CFU-E (CFU-erythroid)] lineages. These intermediate progenitors have more restricted self-renewal capacity and differentiate into mature and functional immune cells (i.e., monocytes, T-cells, B-cells, dendritic cells). Lineage tracing can be performed using cell surface receptors, beginning with CD34+CD38- early HSCs and HPCs, maturation to committed progenitors, then finally mature immune cells that express lineage markers (Lineage+, e.g. CD3+ T-cells or CD14+ monocytes) and lack CD34 expression. Betaherpesviruses infect HPCs and specifically control differentiation to virus-favorable lineages. Highlighted (in color and bold) here with their lineage preferences are HHV-6 or HHV-7 to T-cell differentiation (blue) and HHV-5 (HCMV) to myeloid differentiation (green).