Abstract

Aims:

To summarise the evidence on barriers to and facilitators of population adherence to prevention and control measures for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other respiratory infectious diseases.

Methods:

A qualitative synthesis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. We performed an electronic search on MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO from their inception to March 2023.

Results:

We included 71 studies regarding COVID-19, pneumonia, tuberculosis, influenza, pertussis and H1N1, representing 5966 participants. The measures reported were vaccinations, physical distancing, stay-at-home policy, quarantine, self-isolation, facemasks, hand hygiene, contact investigation, lockdown, infection prevention and control guidelines, and treatment. Tuberculosis-related measures were access to care, diagnosis and treatment completion. Analysis of the included studies yielded 37 barriers and 23 facilitators.

Conclusions:

This review suggests that financial and social support, assertive communication, trust in political authorities and greater regulation of social media enhance adherence to prevention and control measures for COVID-19 and infectious respiratory diseases. Designing and implementing effective educational public health interventions targeting the findings of barriers and facilitators highlighted in this review are key to reducing the impact of infectious respiratory diseases at the population level.

Short abstract

Knowledge about disease, susceptibility, collective responsibility, health policies, access to information, and psycho-cognitive, socio-environmental and other aspects may affect adherence to measures for preventing respiratory infectious diseases https://bit.ly/3nUieb2

Introduction

Respiratory infectious diseases are pathological conditions transmitted from one person to another by a single agent. These conditions impact individuals’ health and impose a burden on the health system and society (i.e. affecting the economy and limiting travel and socialisation) [1]. The emergence and spread of these pathogens over time significantly impact global health and economies. Consequently, prevention measures to decrease the burden on society have become an important goal for public health [2, 3].

In the last two decades, the coronavirus caused two outbreaks similar to the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (SARS-CoV-2), impacting public health, mental health and overall well-being worldwide [4, 5]. In the absence of specific vaccines for SARS-CoV-1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome, measures such as the immediate isolation of confirmed cases and the use of protective equipment during patient management helped to prevent the spread of disease [6].

COVID-19 quickly spread worldwide and culminated in a global pandemic, reaching more than 200 countries and territories, affecting around 761 402 282 million people, and causing 6 887 000 deaths up to 29 March 2023 [7].

Since the spread of COVID-19, prevention measures have been widely established to improve hygiene habits and decrease contamination rates [8]. Main interventions include using facemasks, lockdown impositions, physical distancing and promoting educational programmes and vaccination campaigns. Some countries implemented a range of strategies to prevent the COVID-19 outbreak, which seemed efficient when populations were receptive [9]. However, adherence to prevention recommendations depends on individual behaviour, and reaching optimal adherence levels is challenging [10].

Tuberculosis (TB) and other respiratory infections such as pneumonia are among the leading infectious diseases globally, considering disability-adjusted life years or the number of infected individuals [11, 12]. Despite efforts over time to control TB, it is still one of the most serious diseases in the world and is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Preventive treatment is the main health intervention available to reduce the risk of TB infection [13]. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, TB was the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, ranking above HIV/AIDS [14]. Although TB can be cured, non-adherence to treatment is still the main challenge to its prevention and control [15].

In addition, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has a high morbidity and mortality rate worldwide, and Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most prevalent pathogen among the aetiological agents of CAP [16]. The main strategy for preventing CAP, especially in an at-risk population, is the pneumococcal and influenza vaccination. But, despite this, adherence is low even in vulnerable people [17, 18].

Different precautionary measure frameworks, such as the Health Belief Model (HBM) [19], may facilitate population-level adherence to prevention measures for respiratory infectious diseases. Contrarily, doubtable beliefs and misinformation may lead to resistance to preventive behaviours [20] and decrease adherence to these measures, indicating an urgent need to minimise barriers that hinder adherence to COVID-19 prevention measures [21]. This qualitative evidence synthesis aimed to summarise evidence on barriers to and facilitators of population-level adherence to prevention and control measures of COVID-19 and other respiratory infectious diseases.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review according to the protocol registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42020205750) [22]. We also followed the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [23] and the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis [24].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies that used both qualitative data collection and analysis methods, and mixed-methods studies with qualitative analysis methods. Studies published at any time in English, Portuguese and Spanish were included. The review focused on adults (≥18 years) who received protective behaviour recommendations for various strategies to combat COVID-19 and other respiratory infectious diseases. We did not include studies of protective recommendations for healthcare professionals (HCPs).

We excluded systematic reviews, books, policy reports, editorials, letters to the editor, conference papers, abstracts, expert reviews, studies that collected data using qualitative methods but did not use qualitative analysis methods, and unpublished and non-peer-reviewed studies.

Search strategy

A systematic electronic search using pre-established strategies was performed in the following databases from their inception to the present: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and PsycINFO. We did not include a methodological filter for qualitative studies because this would have limited our ability to retrieve mixed-methods studies. We checked reference lists of all primary included studies and reviewed articles for additional references. The proposed search strategy for all searched databases is shown in the supplementary material.

Study selection

After removing duplicates using Mendeley Reference Manager (version 2.80.1), two review authors (TZ and SL) independently screened titles and abstracts using Rayyan QCRI systematic review web-based application software [25]. The full text of relevant studies was retrieved and independently screened for inclusion. The review authors identified and recorded the reasons for the exclusion of ineligible studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third review author (KMPPM) when necessary. The selection process was recorded in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction

Two review authors (TZ and JCA) extracted data independently into a data extraction form designed for this synthesis. Two additional review authors (THSP and GRS) checked for inconsistencies and completeness of extracted data. We extracted the following study characteristics: year, aims and purpose, study design, setting, type of respiratory disease, population, qualitative sample size, characteristics of participants (age, gender, country), data collection methods, type of control and prevention measures, outcome(s) and result(s).

Quality assessment

Two review authors (TAS and KSM) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [26], which includes the following domains: clarity of aims; appropriateness of qualitative methodology, research design, recruitment strategy and data collection method; consideration of reflexivity and ethical issues; rigour of analysis; clarity of findings; and the value of the research. We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus involving a third review author (KMPPM).

Assessment of confidence in the synthesised findings

Two review authors (TZ and GC) independently assessed the confidence in the evidence of each finding using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) approach [27]. GRADE-CERQual is designed to assess confidence in the evidence based on four key components: 1) methodological limitations, which assess if there are concerns regarding the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed to the review finding; 2) coherence, which assesses the fit between the data from the primary studies and the review finding; 3) adequacy of data, which assesses the richness and quantity of data that support the review finding; and 4) relevance, which assesses the body of evidence (i.e. population, setting, the phenomenon of interest) from the primary studies that support the review finding. We examined each review finding to identify factors that may influence the implementation of the intervention and implications for practice. The overall confidence was classified as high, moderate, low or very low for each key component. Finally, we presented the summary of findings and provided the assessment of confidence in tabular form.

Data analysis

We followed the best-fit framework approach as the strategy for data analysis and synthesis. We used the five stages of the best-fit framework: familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, mapping and interpretation [28].

We used adapted dimensions derived from the HBM [29] and the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [30] frameworks. Six dimensions are posited as health behaviour predictors by the HBM (risk susceptibility, risk severity, benefits to action, barriers to action, self-efficacy and cues to action). This model has been used for health prevention-related and asymptomatic concerns where beliefs are as relevant or more relevant than evident symptoms [31]. In the BCW, the COM-B model states that capability (C), opportunity (O) and motivation (M) are essential components to change behaviour (B) [30].

After data extraction, two review authors reread the findings of the included studies, and the emerging themes were analysed across the framework (TZ and BAKS). To complete the evidence synthesis focused on the review question, aims and context, we subsequently rearranged and explored data while charting, mapping and interpreting the concepts.

To facilitate understanding of the results, we grouped the findings of barriers and facilitators into thematic axes after their classification into framework dimensions.

Results

Differences between the protocol and the systematic review

This study was initially planned as a rapid qualitative synthesis of the available evidence published through to 2023. The first electronic search performed in November 2020 resulted in the inclusion of 14 studies. However, none of the included studies was related to measures to prevent COVID-19. This finding highlighted that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies could be in progress. Additionally, many countries had no vaccination campaigns against COVID-19 at that time. Thus, we extracted and analysed the available data and updated the search in December 2021 and March 2023. The subsequent searches aimed to retrieve studies covering the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination as a preventive measure. For these reasons, we changed the title of this study from “Barriers and facilitators to populational adherence to prevention and control measures of COVID-19 and other respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis” to “Barriers of and facilitators to populational adherence to prevention and control measures of COVID-19 and other respiratory infectious diseases: a qualitative evidence synthesis”.

Search strategy

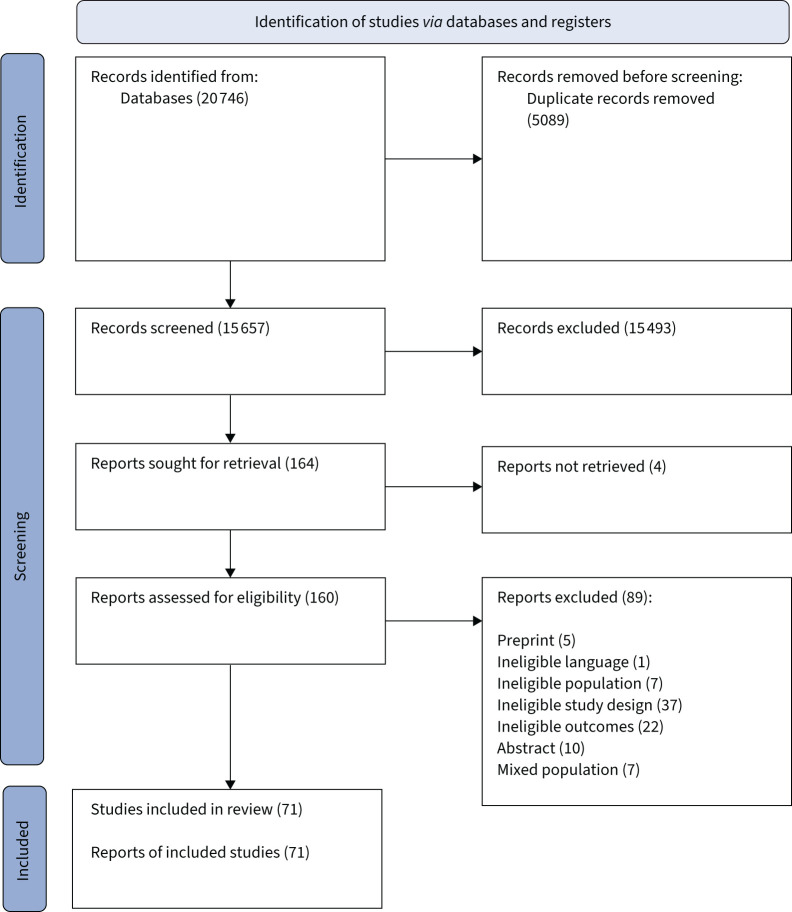

Databases were searched from their inception to 6 November 2020 and then updated on 22 December 2021 and 7 March 2023. Database searches returned 20 746 references, resulting in 15 657 references after removing duplicates. No additional references were obtained by searching other sources. Of these, 15 493 records were excluded, and 164 were identified as potentially relevant. The full text of 160 articles was retrieved for closer inspection. A total of 71 studies were included. The PRISMA flow diagram shows the results of the search and selection process (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

This review included 71 studies representing 5966 participants. Of these, 54 reported qualitative methods only and 17 used mixed-methods approaches. 20 studies were from North America [32–51], 17 from Europe and Central Asia [52–68], 13 from East Asia and the Pacific [69–81], five from South Asia [82–86], 11 from Sub-Saharan Africa [87–97], three from the Middle East and North Africa [98–100] and two from Latin America and the Caribbean [101, 102]. According to the World Development Indicators 2022–2023 of the World Bank [103], 45 of the included studies were from high-income countries [32–69, 71–74, 77, 79, 81], five were from upper-middle-income countries [70, 75, 78, 101, 102], 10 were from lower-middle-income countries [76, 82–86, 88, 97, 99, 100] and 10 were from low-income countries [87, 89–96, 98]. Most participants were young and middle-aged adults, and only 10 studies focused on older people [33, 38, 41, 45, 70, 71, 74, 77–79]. Five studies did not report detailed information regarding participants’ age [40, 64, 96, 98, 99].

Most included studies focused on barriers and facilitators to prevent and control COVID-19 [32, 34, 37, 39, 40, 43, 44, 46–54, 58, 60, 62–64, 66–68, 70, 72, 76, 80–82, 85–88, 92, 94, 95, 97, 98, 100, 102] and influenza [35, 36, 38, 41, 42, 45, 55, 57, 59, 61, 65, 69, 71, 74, 75, 78, 79, 99, 101]. Other studies focused on TB [56, 83, 84, 89–91, 93, 96, 102], pneumonia [33, 35, 38, 77, 79] and pertussis [57, 65, 73]. The control and prevention measures were vaccination, physical distancing, stay-home policy, facemasks, hand hygiene, contact investigation, quarantine, self-isolation, lockdown, infection prevention and control guidelines, and treatment. Access to care, diagnosis and treatment completion were control and prevention measures related to TB. In geographic terms, most included studies on vaccination and facemask use were conducted in the USA. Most included studies on physical distancing and self-isolation were conducted in the UK. African countries had proportionally more studies on hand hygiene and adherence to TB treatment. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of included studies and presents the respiratory infectious diseases and control and prevention measures related to each study.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author [ref.] | Country | Study design | Qualitative methods of data collection | Participants (n) | Respiratory infectious disease | Type of control and prevention measures | Females (%) |

| Ag Ahmed [ 87 ] | Mali | Qualitative | Semi-structured face-to-face individual interviews | 61 internally displaced people | COVID-19 | Physical distancing | 37 |

| Akeju [ 88 ] | Nigeria | Mixed method | In-depth interviews | 22 Nigerians adults# | COVID-19 | Stay-home policy | 59.1 |

| Akter [ 82 ] | Bangladesh | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 10 refugees | COVID-19 | IPC guidelines | 40 |

| Alqahtani [ 69 ] | Australia | Qualitative | Face-to-face in-depth interviews | 10 Australian Hajj pilgrims | Influenza | Facemasks, hand hygiene, physical distancing and vaccine | 40 |

| Anderson [ 52 ] | England | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews via phone calls or video | 31 pregnant women | COVID-19 | Lockdown and physical distancing | 100 |

| Arreciado Marañón [ 65 ] | Spain | Qualitative | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 18 pregnant women | Influenza and pertussis | Vaccine | 100 |

| Ayakaka [ 89 ] | Uganda | Qualitative | Focus group discussion and interviews | 36 household contacts of newly diagnosed patients with TB | TB | Contact investigation | 53 |

| Bateman [ 32 ] | USA | Qualitative | Online focus group discussion | 36 African American residents | COVID-19 | Prevention, coping and testing | 7 |

| Benham [ 48 ] | Canada | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews and online focus groups | 50 Alberta province residents | COVID-19 | Stay-home policy, physical distancing, facemasks, contact investigation and vaccine | 60 |

| Blake [ 53 ] | England | Qualitative | Online focus group discussion | 25 university students | COVID-19 | Physical distancing and self-isolation | 64 |

| Brown [ 33 ] | USA | Mixed method | Semi-structured interviews with open-ended question | 40 older Black patients# | Pneumonia | Vaccine | 95 |

| Burton [ 68 ] | UK | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | 116 residents | COVID-19 | Physical distancing | 61 |

| Carcelen [ 101 ] | Peru | Qualitative | Semi-structured in-depth face-to-face interviews | 12 pregnant women | Influenza | Vaccine | 100 |

| Carson [ 34 ] | USA | Qualitative | Online focus group discussion | 70 members of racial and ethnic minority groups | COVID-19 | Vaccine | 71.4 |

| Chen [ 70 ] | China | Qualitative | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 35 older Chinese people | COVID-19 | Vaccine | 68.6 |

| Claude [ 94 ] | Democratic Republic of Congo | Mixed methods | Focus group discussion | 23 refugees and internally displaced persons# | COVID-19 | Physical distancing, hand hygiene and vaccine | 37.4 |

| Colmegna [ 35 ] | Canada | Qualitative | Focus group discussion and semi-structured open-ended individual interviews | 28 adults with an established rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis | Influenza and pneumonia | Vaccine | 82 |

| Cummings [ 71 ] | Singapore | Qualitative | Personal one-on-one interviews | 76 older people | Influenza | Vaccine | 60.5 |

| Davis [ 81 ] | Australia | Qualitative | Semi-structured phone interviews | 25 Australian residents | COVID-19 | Quarantine and self-isolation | 60 |

| DeJonckheere [ 49 ] | USA | Mixed methods | Open-ended text message survey | 479 American youths | COVID-19 | Facemasks | 51.8 |

| Denford [ 67 ] | England | Qualitative | Interviews via phone or online platform Zoom | 20 individuals from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups | COVID-19 | Physical distancing and self-isolation | 65 |

| Dixit [ 83 ] | Nepal | Qualitative | Focus group discussion | 21 people with TB 13 community stakeholders |

TB | Treatment | NR |

| Douedari [ 98 ] | Syria | Qualitative | Online face-to-face interviews | 20 displaced Syrians in opposition-controlled camps | COVID-19 | Hand hygiene, physical distancing, staying home, lockdown and curfew | 65 |

| Eraso [ 66 ] | UK | Mixed methods | Phone interviews or online video interviews via Zoom or Skype | 16 residents | COVID-19 | Quarantine and self-isolation | 50 |

| Farrell [ 62 ] | Republic of Ireland | Qualitative | Semi-structured one-on-one phone or online interviews | 25 residents in Ireland | COVID-19 | Physical distancing | 56 |

| Ferng [ 36 ] | USA | Mixed methods | Focus group discussion and home visits | 12 urban Hispanic households# | Influenza | Facemasks | 98 |

| Franke [ 96 ] | Madagascar | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions | 32 patients with TB | TB | Treatment | NR |

| Gallant [ 61 ] | Scotland | Mixed methods | Focus group discussion and one-on-one interviews | 160 adults with chronic respiratory conditions# | Influenza | Vaccine | 70 |

| Gasteiger [ 72 ] | New Zealand | Mixed methods | Online survey with open-ended question | 373 residents across New Zealand# | COVID-19 | Contact investigation mobile application | 90 |

| Gauld [ 73 ] | New Zealand | Mixed methods | Personal semi-structured interviews | 37 women who had given birth to a child in the last 12 months# | Pertussis | Vaccine | 100 |

| Gebremariam [ 90 ] | Ethiopia | Qualitative | Focus group discussion and individual interviews | 15 TB/HIV co-infected patients | TB | Treatment | NR |

| Gebreweld [ 91 ] | Eritrea | Qualitative | In-depth interviews, focus group discussion and key informants | 36 patients with TB | TB | Treatment | 51.2 |

| Gonzalez [ 37 ] | USA | Qualitative | Online semi-structured interviews | 20 Hispanics in New York City | COVID-19 | Physical distancing | 65 |

| Ha [ 80 ] | Vietnam | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 26 migrant workers and community representatives | COVID-19 | Contact investigation, self-isolation and facemasks | 26 |

| Hailu [ 92 ] | Ethiopia | Mixed methods | Phone interviews | 12 key representative informants of the community# | COVID-19 | Physical distancing | 28.9 |

| Harris [ 38 ] | USA | Mixed methods | Semi-structured in-depth interviews | 20 older Black patients# | Influenza and pneumonia | Vaccine | 70 |

| Harris [ 39 ] | USA | Qualitative | Interviews via phone, video conference and in person | 32 immigrant community members | COVID-19 | Hand hygiene, facemasks and physical distancing | 56.3 |

| Hassan [ 60 ] | England | Qualitative | Focus group discussion and one-on-one interviews | 47 Muslim community members | COVID-19 | Physical distancing, hand hygiene and quarantine | 52 |

| Jimenez [ 50 ] | USA | Qualitative | Online group and individual interviews | 111 members of Black and Latinx communities | COVID-19 | Facemasks, testing and vaccine | 78.4 |

| Jones [ 40 ] | USA | Mixed methods | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 39 business owners or supervising employees# | COVID-19 | Facemasks | NR |

| Karat [ 56 ] | England | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 18 patients with TB 4 caregivers of patients with TB |

TB | Treatment | 18.2 |

| Knights [ 58 ] | England | Qualitative | In-depth semi-structured phone interviews | 17 migrants | COVID-19 | Vaccine and primary care | 64.7 |

| Lohiniva [ 99 ] | Morocco | Qualitative | Focus group discussion and in-depth interviews | 123 pregnant women | Influenza A H1N1 | Vaccine | 100 |

| Mackworth-Young [ 97 ] | Zimbabwe | Qualitative | Phone interviews | 4 representatives of community-based organisations | COVID-19 | Physical distancing, hand hygiene and lockdown | 75 |

| Mahmood [ 64 ] | England | Qualitative | Phone or online interviews via Zoom | 19 ethnic minority community leaders | COVID-19 | IPC guidelines | 47.3 |

| Maisa [ 57 ] | Northern Ireland | Qualitative | Focus groups discussion and in-depth interviews | 15 pregnant women | Pertussis and influenza | Vaccine | 100 |

| Marahatta [ 84 ] | Nepal | Qualitative | Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews | 4 patients with TB 16 patients with suspected TB 24 health workers 2 traditional healers 8 community members |

TB | Access, diagnosis and treatment completion | NR |

| McIntyre [ 41 ] | Canada | Qualitative | Focus group discussion | 37 older people | Influenza | Vaccine | 70.2 |

| Momplaisir [ 42 ] | USA | Qualitative | Focus group discussion | 24 Black barbershop and salon owners | Influenza | Vaccine | 74 |

| Montgomery [ 51 ] | USA | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 51 people experiencing homelessness | COVID-19 | Hand hygiene | 49 |

| NeJhaddadgar [ 100 ] | Iran | Qualitative | Phone, face-to-face and video interviews | 45 Iranian people | COVID-19 | IPC guidelines and treatment | 48 |

| Okoro [ 43 ] | USA | Mixed methods | Focus group discussion and one-on-one interviews | 79 members of the Black/African American community# | COVID-19 | Vaccine and testing | Focus group: 53.1 Interview group: 53.3 |

| Osakwe [ 44 ] | USA | Qualitative | Semi-structured one-on-one interviews | 50 Black and Hispanic individuals | COVID-19 | Vaccine | 64 |

| Phiri [ 93 ] | Malawi | Qualitative | In-depth interviews and participatory workshops | 53 residents of informal settlement | TB | Diagnosis and treatment | 50.9 |

| Ridda [ 77 ] | Australia | Qualitative | Open-ended interviews | 24 hospitalised older people | Pneumonia | Vaccine | 54.1 |

| Santos [ 102 ] | Brazil | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | 7 people being treated for TB | TB and COVID-19 | IPC guidelines and treatment | 57 |

| Santos [ 55 ] | Portugal | Mixed methods | Survey with open question via phone calls | 399 high-risk individuals# | Influenza | Vaccine | 53.7 |

| Sebong [ 76 ] | Indonesia | Qualitative | Semi-structured in-depth interviews and framework analysis (telephone or face-to-face) | 19 dormitory residents 3 staff 1 dormitory manager |

COVID-19 | Hand hygiene, facemasks and physical distancing | 100 |

| Sengupta [ 45 ] | USA | Qualitative | Open-ended interview | 28 older African Americans living in North Carolina | Influenza | Vaccine | 78 |

| Shahil Feroz [ 86 ] | Pakistan | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews via Zoom or Skype | 27 Muslim community members | COVID-19 | IPC guidelines | 52 |

| Shelus [ 46 ] | USA | Qualitative | Online focus group discussion | 34 residents of North Carolina | COVID-19 | Facemasks | 82 |

| Sialubanje [ 95 ] | Zambia | Qualitative | In-depth interviews | 45 community members | COVID-19 | Hand hygiene, facemasks and physical distancing | 60 |

| Siu [ 79 ] | Hong Kong | Qualitative | Semi-structured in-depth individual interviews | 40 Hong Kong citizens | Influenza and pneumonia | Vaccine | 67.5 |

| Sun [ 75 ] | China | Mixed methods | Focus group discussion and telephone survey | 54 Chinese general public# | Influenza | Vaccine | Focus group: 64.8 |

| Teo [ 74 ] | Singapore | Qualitative | Face-to-face interviews | 15 older people | Influenza | Vaccine | 46.6 |

| Van Alboom [ 54 ] | Belgium | Mixed method | Open-ended question | 2055 Belgian adults# | COVID-19 | Physical distancing | 70 |

| Walker [ 47 ] | USA | Qualitative | Phone discussion | 25 mothers affiliated with a parent advisory group | COVID-19 | Vaccine and protective behaviours | 100 |

| Williams [ 59 ] | UK | Mixed methods | Focus group discussion and interviews | 59 adults with chronic respiratory conditions# | Influenza | Vaccine | 70 |

| Zakar [ 85 ] | Pakistan | Qualitative | Online-based in-depth interviews or via phone calls | 34 members of general public | COVID-19 | Hand hygiene, facemasks and physical distancing | 28.6 |

| Zhang [ 78 ] | China | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | 137 older people living in Hong Kong | Influenza A and H1N1 | Facemasks | 91.2 |

| Zimmermann [ 63 ] | Germany and Switzerland | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | 77 people living in Germany and Switzerland | COVID-19 | Facemasks, physical distancing, staying home and lockdown | 52 |

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; IPC: infection prevention and control; TB: tuberculosis; NR: not reported. #: participants of the study with mixed methods who had data analysed using qualitative methods.

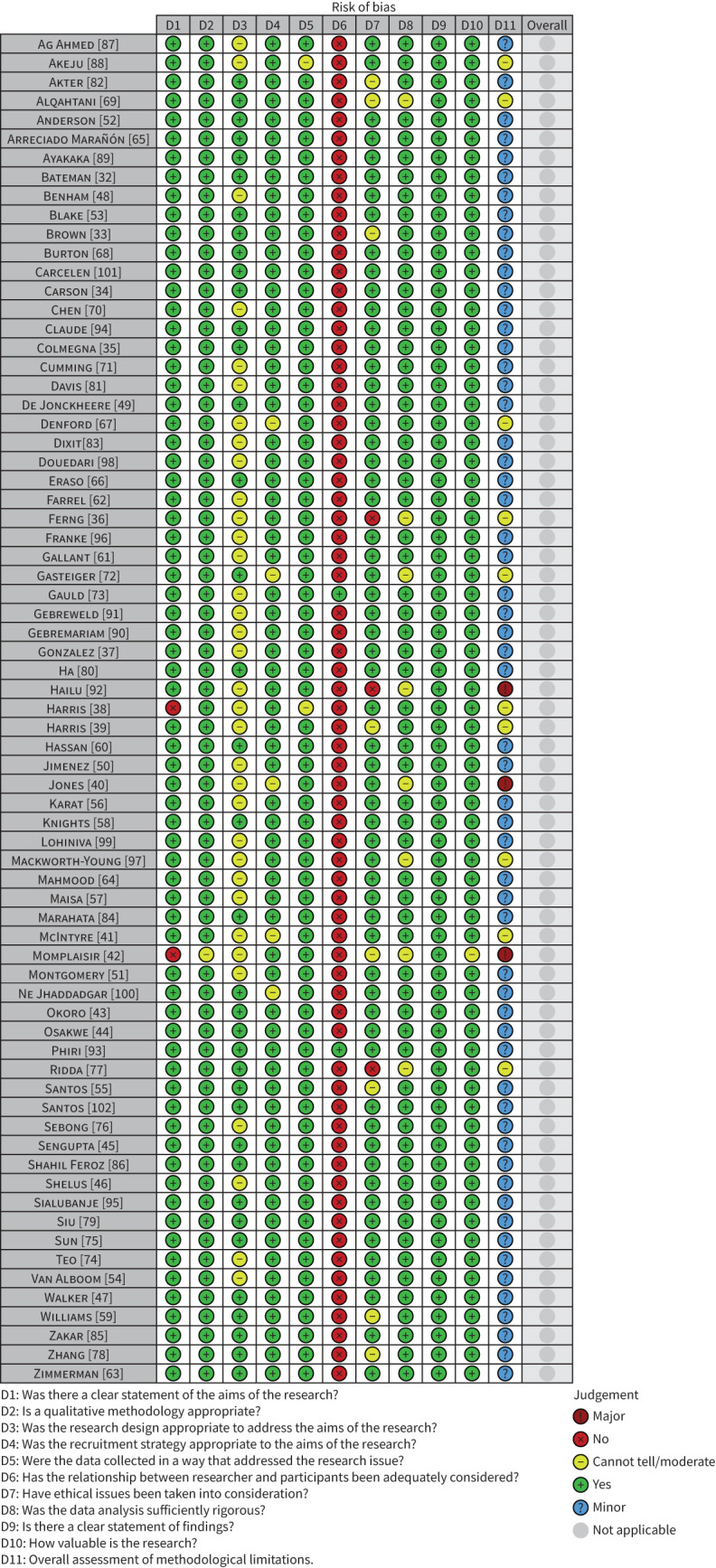

Quality assessment of included studies

Most studies were assessed as having appropriate rigour. However, some studies did not report some relevant aspects. This included 34 studies that did not provide sufficient information to justify if the research design was appropriate to address the aims of the study [36–42, 46, 48, 50, 51, 54, 56, 57, 61, 62, 64, 67, 70, 71, 73, 74, 76, 81, 83, 87, 88, 90–92, 96–99], and five studies that did not report how participants were selected, limiting our judgement on the appropriateness of the recruitment strategy [40, 41, 67, 72, 100]. All studies provided a clear statement of findings, but only two studies explored the relationship between the researcher and participants regarding their role, potential bias and influence [73, 93]. Full details of risk of bias for each included study can be found in figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Risk of bias assessment.

Review findings

Detailed analysis of the 71 studies identified both barriers (n=37) and facilitators (n=23) and were categorised into 10 dimensions derived from the HBM and the COM-B model. The five from the HBM were perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, perceived susceptibility and cues to action, and from the COM-B model were psychological capability, physical opportunity, reflexive motivation, automatic motivation and social opportunity.

Given the diversity of findings, we grouped them into 10 main themes (i.e. financial aspects; previous knowledge about diseases; access to information; sense of collective responsibility; accessibility and availability of measures; psycho-cognitive factors; health policies; socio-environmental factors; self-perception of susceptibility; and trust in authorities, health professionals and close people). Table 2 shows the 60 findings classified into 10 dimensions and 10 themes.

TABLE 2.

Findings of barriers and facilitators classified into dimensions derived from the frameworks of the Health Belief Model (HBM) and the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour model (COM-B)

| Findings | Example quote | Framework dimensions |

| Theme 1: Previous knowledge about diseases | ||

| Lack of knowledge and familiarity with the disease | “I think influenza and flu are about the same family, quite the same. Flu may be passing flu, sometimes flu may come and go but influenza may be more serious, I don't know. I think so, so I think.” [71] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Absence or low perceived need to wear facemasks | “There is no pressure for me, I am not afraid. So, I don't wear facemasks.” [78] | Perceived severity (HBM) |

| Awareness about the seriousness of the outbreak | “…more lethal than any other disease: cholera, Ebola” [97] | Perceived severity (HBM) |

| Knowledge about transmission of infectious respiratory diseases | “I am afraid that I will be infected, and many people are infected during the pandemic. Because it will be easily infected, it is necessary to wear a facemask to protect myself.” [78] | Perceived susceptibility (HBM) |

| Theme 2: Financial aspects | ||

| Food and financial insecurity limiting adherence to pharmacological treatment | “I had to come every day for injections. I tell you the truth, there was a time when I had to sell my jewellery: my rings, my necklace, everything. I had to run here without even eating breakfast.” [90] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Food and financial insecurity limiting adherence to nonpharmaceutical measures | “In the morning, you have no resource for providing food while eating is a necessity. If you're hungry, you need to go out to try and find something. When you have the means to eat, you can stay home.” [87] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Financial and social support for pharmacological treatment | “My family members supported me a lot. They encouraged me. After the TB, when they found the HIV, I wanted to die. I did not want to live. But my families, especially my brothers and sisters, they said: you are not the only one. Look, many people have this.” [90] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Financial and social support to adhere to nonpharmaceutical measures | “The campaign group just gave information, then the household would support. There were organisations and individuals had brought the money to support for the activities of COVID-19 prevention and control.” [80] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Theme 3: Access to information | ||

| Lack of knowledge regarding government support for getting vaccinated and misperceptions about the vaccine cost | “Changing the way that you talk about vaccines would change a lot the way people would feel about having vaccines.” [35] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Awareness about vaccination benefits, safety and effectiveness | “I think it [flu shot] keeps my immune system stronger, so therefore I feel better, and I'm able to do the things that I enjoy doing and not have to spend time laying around, sneezing, coughing…so it really helps me so I can be more active.” [45] | Perceived benefits (HBM) |

| Lack of knowledge about vaccine availability | “I did not hear anything about this vaccine. I did not know people were taking it.” [99] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Fake news (misinformation and disinformation) about vaccines | “[Social media groups] were spreading a lot of information like ‘don't go outside tonight because the government will be spreading the powder that will stop COVID’. And the funny thing is people believe it because somebody sent them [the information]…Like I see in the Russian-speaking group on Facebook so much confusion, so much misunderstanding of the system…I think this is where people make decisions. They will not trust a GP. Even after 16 years in the country.” [58] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Quality information released by religious leaders | “I heard from the mosque and the next day I went to get the vaccine against H1N1.” [99] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Pre-warning from healthcare providers regarding how to cope with side-effects from vaccines | “…they say now you take you go home, tomorrow, if there is fever for a while it is okay, for one or two days like that…then after I took it I got fever lot, but I know one or two days can recover already, then it is okay…Doctor and nurse say like that, and it is correct.” [74] | Cues to action (HBM) |

| Quality information on nonpharmaceutical measures on specialist websites, social media and television | “[I get information] from the internet mostly, because we don't have electricity [for TV]. Among every 2–3 households, one would have electricity and neighbours would come and charge their [phone] batteries…so we don't have TV. We get all news through our mobile phones.” [98] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Campaigns for pro-vaccination in social media and television, in addition to written or visual media | “I think when you get information when you go to get your flu shot, they also give you pamphlets to hand out and things like that, I think that all is a good awareness.” [45] | Cues to action (HBM) |

| Misperceptions about vaccines' role, formulation process, testing, targets and vaccination protocols | “I'm not comfortable with that kind, keep on testing and testing, they also didn't have enough long-time research. Too new.” [71] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Misperceptions about vaccines' effectiveness, safety and side-effects | “There are people that say that if you get vaccinated, sometimes, it's like they give you the virus. So, you can get the disease, and it wouldn't happen if they didn't vaccinate you.” [65] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Difficulties in accessing information via digital technologies | “A lot of the older generation, that's including myself, are not computer savvy enough to do it.” [32] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Insufficient information and fake news about nonpharmaceutical measures |

“What we need is more information [of mask use] in our community.” “We need programmes like these in schools so the children can learn [about masks] and to raise awareness.” [36] |

Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Theme 4: Sense of collective responsibility | ||

| Positive attitudes and engagement with vaccination to maintain health and protect others | “I was hoping that I will not get the flu, otherwise I will just spread it throughout everybody you know, in my family and friends or whatever.” [74] | Reflexive motivation (COM-B) |

| Indiscipline and lack of collective responsibility for other people | “It was a little bit galling to see neighbours with their families popping in and out. And yet we're not in that position and if our families had been nearby maybe that temptation would've been huge.” [68] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| The sense of collective responsibility to protect self and others through nonpharmaceutical measures | “Yes, the most important thing is to protect yourself and then to protect the whole community. The basic rule is that when you get sick, you will not infect others. So, there will be no infection in the community. And, it will become serious for the disease to spread from person to person.” [78] | Reflexive motivation (COM-B) |

| Theme 5: Accessibility and availability of measures | ||

| Logistical difficulties in acquiring facemasks | “Yes, I will wear facemasks when my children buy them. And, when many facemasks are available.” [78] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| The availability of facemasks | “Authorities having/making [masks] available to give out” [40] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| The practicality of hand hygiene (handwashing and antiseptics) | “At Hajj especially in crowded places, it was easier to use the antiseptic wipes and hand sanitiser gel than other methods. It is easy, convenient and effective way to prevent infections.” [69] | Cues to action (HBM) |

| Access barriers and conflicts of time to take the vaccination | “I am not motivated to get vaccinations because I have to go to a clinic to get them. I have to wait in the clinic with other patients who are coughing and sneezing.” [79] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Need to travel to have access to pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical measures | “Sometimes the challenge is transport, you can't walk to the clinic, so you just sit at home. If you have some money, you are able to visit the clinic, because there are lots of minibuses or bicycle taxis out there.” [93] | Physical opportunity (COM-B) |

| Easily accessible locations for vaccination and pharmacological treatment | “I live so close to the pharmacy so it's easily accessible. A lot of people where I live would be more likely to visit a pharmacy I'd think since they don't have cars.” [73] | Physical opportunity (COM-B) |

| Theme 6: Psycho-cognitive factors | ||

| Fatalism | “If you talk about death ah…anything can [cause] death…not because of flu. Cause death, life ah is in the hands of God, even if Bruce Lee, you see very strong, died in the sleep.” [74] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Personal beliefs against the adoption of nonpharmaceutical measures | “I refuse to adhere to illegitimate decisions of an illegal government, as they are unlawfully and undemocratically appropriating the power to violate my right to self-determination, to privacy and basic human rights.” [54] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Fear of vaccination (e.g. fear of injections, pain and side-effects) | “Yes my problem is not with the vaccine it is because I have terrible anxiety disorder and fear of needles.” [61] | Psychological capability (COM-B) |

| Individual perceptions of self-defence and self-efficacy with own health | “Strong people are strong so they don't need [the influenza vaccine].” [71] | Psychological capability (COM-B) |

| Lack of social interaction and physical contact | “I followed it religiously for 7 weeks and it got to the point where I was just, not depressed every day but I was just thinking I don't have any motivation to work. I'm not sleeping at all. I've always been a touchy feeling person. I need someone to hug that isn't mum or dad.” [68] | Psychological capability (COM-B) |

| Forgetting to use nonpharmaceutical measures | “I do meet up with certain friends that I would see often enough and my bandmates to be included in that, like we do kind of let our guard slip the odd time and I think that's almost like human nature as well.” [62] | Psychological capability (COM-B) |

| Fear of stigmatisation | “Even if people are doing their normal activities, I feel that they are looking at me. When I come every day carrying the water bottle I feel ashamed so I hide it in my bag.” [91] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Theme 7: Health policies | ||

| Dissatisfaction related to pharmacological treatment regimen and healthcare | “Swallowing so many drugs, it was very difficult. I was scared that it would harm my body. Drugs can harm you if they are too many.” [90] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Free vaccine or government financial support for vaccinating | “I think people will say it's expensive for Singaporeans who don't have enough money. The government has to subsidise a bit for the poor people.” [71] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Dissatisfaction with supportive policies, health services and professional care | “Since they've started changing it, God knows. Nobody's got a clue. It changes every day, because ministers have got to stand up and have something to announce, so how would anybody know? There's no time for it to embed.” [68] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Lack of obligation and monitoring for adherence to nonpharmaceutical measures | “Many people are indifferent to corona because there is no penalty. Most of them have returned to normal life. They believe in the existence of the coronavirus only when the government close places.” [100] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Contact tracing measures and testing | “I think it's a good idea in terms of—because obviously the whole point of wider testing means you've got a better ability to potentially control the virus and that's, like, in all other countries that have done good control and lots of testing is seen as a good thing.” [53] | Perceived benefits (HBM) |

| The direct or indirect warning to wear facemasks and physical distancing (e.g. social pressure, the example of other people) | “The regulations at restaurants and bars are so restricted already, that I and they're also following every single one of the guidelines…So I feel safe-ish, especially on a patio or something.” [48] | Cues to action (HBM) |

| Theme 8: Socio-environmental factors | ||

| Poor sanitation conditions, access to water and housing | “I live in the interior of the city where there are small houses with a high population density. Experts are talking about social distancing and handwashing. How can my family and I follow these measures when there is no proper sanitation facility available in our home to wash our hands frequently with soap and water?” [85] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Impossibility of working from home | “My husband, my daughter, they are both essential workers. They both have to go out. They both have to work.” [37] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Personal factors (e.g. ethnicity, anti-vaccination groups and deprived areas) | “Our concern is safety. Even that vaccine doesn't matter to us. Let them keep it over there. Even if they vaccinate us, and we continue to live in these conditions, what's the point?” [94] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Difficulties in adopting physical distancing and self-isolation in crowded places and public transport | “And it is even difficult because when it comes to grocery stores, there's no feet social distance in every area.” [39] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Difficulties with breathing, discomfort and social inconvenience with the use of facemasks | “It's very uncomfortable…it's very hot, but I'll pull it off or away from my face for a couple of seconds. And I'll put it right back on.’ [46] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Cultural differences and communication problems to vaccination | “Western medicine is too strong and forceful, and the drugs are all artificial chemicals. It is not good to take vaccines because they are chemicals. Chinese medicines are all herbs, so they are more natural. I prefer taking Chinese medicine to keep up my health instead of vaccines.” [79] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Social role in the family structure and household dynamics | “If we have children and the husband has been sick maybe for a week, you say this man needs to go and work. Maybe [because] you have gone days without eating and the bodies are weak […] this happens in families. For instance, my husband may come back from work feeling really sick with body pains, but if you ask him if he'll go to work, he says, I will go, should I just stay here at home […]” [93] | Social opportunity (COM-B) |

| Cultural differences and communication problems to follow guidelines for nonpharmaceutical measures | “It infuriates me as somebody who works in education, the style of communication that we received from the government. Often messages that are full of difficult vocabulary, idioms, colloquialisms, that I suspect quite a lot of first-language speakers of English wouldn't always follow, let alone speakers of other languages.” [68] | Perceived barriers (HBM) |

| Theme 9: Self-perception of susceptibility | ||

| Scepticism, conspiracy theories and scientific denialism | “There is nothing conclusive. I need to see the corpses. Not until I see a dead body of someone and they say this one has died from COVID-19.” [95] | Perceived susceptibility (HBM) |

| Perception of personal and environmental vulnerability | “And the reason why I took the flu shot this year is because for the last – since I've made 65 – I see that my resistance to colds and flus are getting worse.” [45] | Perceived susceptibility (HBM) |

| Theme 10: Trust in authorities, health professionals and close people | ||

| Vaccine recommendations from clinicians and encouragement by nurses, family members and friends | “As moms, we don't have as much knowledge as professionals. We should follow the guidance of the Ministry of Health because they are the professionals, and they know what's best.” [101] | Perceived benefits (HBM) |

| Faith and positive attitudes of engagement for adopting prevention and control measures | “We divided shelters in two rooms, an antechamber, and a veranda. Adults stay in the room and children under the veranda. If you have the resources, you can build another shelter in the courtyard.” [87] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Lack of recommendations from health professionals to take the vaccine | “If the vaccines were important, I think the doctors and nurses would have mentioned them to me. If they do not mention them, then the vaccines cannot be very important.” [79] | Reflexive motivation (COM-B) |

| Previous unfortunate experiences with vaccination, healthcare providers or other health services | “I've never had the flu jag and I don't intend getting the flu jag. Everybody I know that gets it, gets the flu and gets it badly. My mother used to get it and she was ill for weeks after it.” [59] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Recommendations from health professionals, religious leaders or family members to avoid the vaccine | “My doctor told me not to take the vaccine because I am pregnant, and nobody knows the disadvantages of this vaccine.” [99] | Reflexive motivation (COM-B) |

| Previous and successful experience with vaccination | “I would receive it. For Ebola, people accepted the vaccine.” [94] | Automatic motivation (COM-B) |

| Trust in health, political and religious authorities for adopting nonpharmaceutical measures | “[The] CDC and then the World Health Organization, they…have like professional workers…in the public health field and they…[do] a lot of research related to COVID, so they are knowledgeable. So that's why I trust them.” [39] | Perceived benefits (HBM) |

| Encouragement of health professionals, family and friends to adhere to pharmacological treatment | “They [health professionals] were very good to me. They are like friends; did you not see? Since my head was not good, they were giving me the drugs in a certain way, in a bag, so that I know which drug to take when, they translated it in Amharic for me. They gave me a watch; they helped me a lot. They were like relatives. I have no words to thank them. I am standing today because of them. They told me what drugs to take at what time.” [90] | Cues to action (HBM) |

GP: general practitioner; TB: tuberculosis; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial aspects

Most studies in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia reported economic difficulties as barriers to adherence to COVID-19 measures. Financial and food insecurity limited prevention and control measure compliance, reducing adherence to pharmacological treatment for TB [83, 84, 90, 91, 96, 102]. Financial and food insecurity also limited adherence to nonpharmaceutical prevention and control measures [32, 37, 39, 53, 58, 60, 82, 85, 87, 88, 90, 91, 93, 94, 98]. In turn, financial and social support were cited as facilitators for adherence to pharmacological treatment [56, 83, 90, 91, 93] and nonpharmaceutical prevention and control measures [32, 40, 51, 60, 80, 81, 87, 88, 98].

Previous knowledge about diseases

Several studies [45, 47, 71, 74, 89–91] point out that the lack of knowledge about respiratory infectious diseases hinders the perception of their severity and adherence to prevention and control measures. Studies also suggested that this aspect negatively affected the willingness to wear facemasks [36, 46, 54, 62, 69, 78, 82]. Conversely, knowledge about transmission risks facilitated the use of facemasks and other preventive and control measures [32, 40, 46, 49, 52, 60, 69, 78, 94]. In addition, awareness about outbreaks or disease severity may facilitate adherence to several prevention and control measures, as shown in studies performed in North America and Sub-Saharan Africa [38, 45, 47, 90, 93, 94, 97].

Access to information

Access to information may influence behaviours that aid in preventing and controlling infectious respiratory diseases. For example, in North America, “fake news” negatively affected adherence to influenza [35, 45] and pneumococcal [35] vaccines. Additional studies from North America [34, 35, 38, 42–45, 47, 48, 50, 59] revealed misperceptions about vaccines (e.g. the role of vaccines, process of testing and formulation, target audience and vaccination protocols). Consequently, pro-vaccination campaigns, written information, social media and television were cited as facilitators of vaccine adherence, especially in North America [35, 44, 45]. By contrast, reports of insufficient information and fake news about nonpharmaceutical measures frequently emerged in studies performed in Europe and Central Asia [52–54, 56, 58, 60, 62–64, 67]. Studies from East Asia and Pacific described a lack of knowledge about vaccine availability [69, 74, 77] and misconceptions about the costs of vaccination programmes offered by the government [69, 71, 75]. Misperceptions about vaccine effectiveness, safety and adverse or side-effects were also frequent in studies across this geographic region [70, 71, 73–75, 77]. Despite these results, studies from several regions showed that HCPs' guidance on adverse effects may facilitate vaccine adherence [35, 44, 74, 101]. In addition, awareness of vaccination effectiveness, benefits and safety may facilitate adherence to this measure [35, 45, 55, 65, 69, 75, 99, 101].

Quality information on websites, social media and television facilitates adherence to nonpharmaceutical prevention and control measures [39, 98]. However, barriers to accessing information via digital technologies still exist [32, 58, 64, 72, 82, 100]. Religious leaders were also mentioned as a source of quality information that may influence vaccine adherence [99].

Sense of collective responsibility

Indiscipline and low awareness of collective responsibility for adherence to physical distancing were relevant barriers in studies from Europe and Central Asia [52–54, 60, 62, 63, 67, 68]. However, participants who also lived in these regions reported a sense of collective responsibility as a facilitator of preventive nonpharmaceutical practices [52, 53, 56, 60, 62, 67, 68]. The perspective of maintaining one's own health and protecting others was a vaccination facilitator frequently reported in studies performed in North America [34, 35, 38, 41–43, 45, 59].

Accessibility and availability of measures

The availability of facemasks may influence population adherence to prevention measures. Studies from North America [32, 40] demonstrated that easy access to facemasks facilitated their use. The practicality of access to handwashing and antiseptics also determined greater adherence to these measures [60, 69].

Inconveniences such as the need to travel to access prevention and control measures emerged as frequent barriers in studies performed in Sub-Saharan Africa [91, 93]. Furthermore, access barriers (e.g. long wait times, time conflicts, lack of opportunity and long distances) made vaccination difficult, particularly in Europe, Central Asia, East Asia and Pacific Islands [55, 57, 58, 61, 70, 71, 73, 74, 79]. In turn, access to nearby vaccination and pharmacological treatment centres facilitated adherence to these measures [35, 41, 61, 73, 83, 91].

Psycho-cognitive factors

Individual perceptions of self-defence and self-efficacy with one's own health represented important adherence limitations in North American studies [34, 35, 38, 43, 45]. Fear of vaccination, injections, pain and side-effects frequently emerged from participants from East Asia and Pacific Islands, Europe and Central Asia and North America [35, 41, 45, 50, 55, 57, 61, 71, 74, 75]. In addition, fear of the social stigma associated with their health conditions and the adoption of prevention and control measures were recurrent in studies performed in Sub-Saharan Africa [87, 89–93]. Regarding adherence to nonpharmaceutical methods, forgetfulness represented a limiting cognitive factor for participants from East Asia and Pacific Islands [76, 78, 80, 82].

Some personal beliefs limited the adoption of nonpharmaceutical prevention and control measures, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia [53, 54, 58, 60, 62, 87, 89, 91–93]. Lack of social interaction and physical contact limited the adoption of nonpharmaceutical prevention measures in studies from Europe and Central Asia [52–54, 60, 62, 63, 68]. Fatalism represented a limiting belief in prevention, especially in studies from East Asia and Pacific Islands [69, 70, 74].

Health policies

Dissatisfaction with supportive policies, health services and professional care were frequent barriers identified in studies from South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia [53, 56, 58, 60, 66, 68, 82–85, 87–91, 93, 94]. Treatment regimens, the number of drugs and healthcare provided represented important barriers to adherence to pharmacological treatment in Sub-Saharan African countries [90, 91, 96]. Studies performed in East Asia and Pacific Islands [70, 71, 75] indicated that free vaccines or governmental financial support to vaccinate improved adherence.

Regarding nonpharmaceutical prevention and control methods, the lack of mandatory and normative monitoring actions for adherence were important barriers [39, 40, 62, 64, 67, 76, 92, 93, 95, 100]. Places with a direct or indirect warning to wear facemasks and physical distancing were identified as facilitators of adherence in different regions [40, 46, 48, 49, 63, 68, 69, 78, 87]. Other reports [32, 53, 72, 80] showed that contact tracing and identifying new cases of infectious respiratory diseases might facilitate adherence.

Socio-environmental factors

Personal factors such as ethnicity, anti-vaccination groups and living in underserved areas were relevant limitations for adherence to vaccination in studies worldwide [50, 73, 94]. However, studies in Sub-Saharan Africa [87, 88, 91, 94, 95, 97] showed that environmental adversities such as access to water, precarious housing and poor hygiene/sanitary conditions were direct limitations for adherence to nonpharmaceutical measures.

Studies performed in Europe [53, 58–60, 64, 67, 68] showed that cultural differences and communication issues were relevant barriers to vaccination and limited adherence to guidelines for nonpharmaceutical prevention and control measures. On the European continent, the social role in the family structure and dynamics exemplifies one of these cultural limitations [52, 54, 64, 66, 68].

The need to use public transport and the difficulty in adopting physical distancing and self-isolation in crowded places were common environmental barriers in studies from the UK [53, 68], North America [32, 37, 39, 51], Indonesia [76] and Belgium [54]. Furthermore, the impossibility of working from home during epidemics limited adherence to nonpharmaceutical measures in Europe and Central Asia [52, 54, 60, 62]. Last, reports of difficulty breathing, discomfort and social inconvenience due to facemasks emerged primarily from North America, East Asia and Pacific Islands studies [36, 46, 69, 76, 78].

Self-perception of susceptibility

The perception of personal susceptibility influenced adherence to prevention and control measures. Scepticism, conspiracy theories and scientific denialism were directly linked to a low perception of susceptibility in reports obtained from North America [32, 33, 35, 38, 40, 41, 43, 46, 59] and Europe and Central Asia [52–55, 58, 60, 62, 65, 68]. However, studies performed in North America [35, 41, 45] reinforced the personal perception of environmental vulnerability as a facilitator for using prevention and control measures.

Trust in authorities, health professionals and close people

Studies performed in North America identified the lack of encouragement and recommendations from health professionals as a limiting factor for adherence to vaccination [34, 35, 43, 44, 47, 50, 59]. Previous unpleasant experiences with health professionals, vaccines or other health services also hindered adherence to vaccination [33, 35, 42]. Vaccine recommendation by clinicians and encouragement by nurses, family members and friends facilitated adherence to vaccination campaigns for people in this region [34, 35, 38, 41–45, 59].

According to studies from North America, East Asia and Pacific Islands, recommendation to avoid vaccines and discouragement by health professionals, religious leaders and families hindered vaccination [35, 41, 45, 58, 71, 73, 75]. In contrast, previous and successful experiences with vaccination during other epidemics in East Asia and the Pacific Islands were reported as facilitators of adherence in some studies [71, 74, 77].

Encouraging adherence to pharmacological treatment by health professionals, family members and friends represented a relevant facilitator in some Sub-Saharan African countries [89–91]. In addition, faith and confident engagement attitudes were seen as facilitators for adopting prevention and control measures in Europe and Central Asia [52, 53, 56, 60, 65, 68]. Studies from North America [32, 39, 40, 46, 48, 49] reported that recommendations from political, health and religious authorities may facilitate the adoption of nonpharmaceutical prevention and control measures.

Confidence in the review findings

Out of 60 findings, 24 were graded as high confidence, 24 as moderate confidence, 10 as low confidence and two as very low confidence using the GRADE-CERQual approach (table 3).

TABLE 3.

CERQual summary of qualitative findings

| Summary of review findings | Studies contributing to the review finding | Finding classification | Infectious respiratory diseases | GRADE-CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation of GRADE-CERQual assessment |

| Previous knowledge about diseases | |||||

| Lack of knowledge and familiarity with the disease | [45, 47, 71, 74, 89–91] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza TB |

High confidence | Included 7 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Awareness about the seriousness of the outbreak | [38, 45, 47, 55, 60, 65, 68, 69, 78, 90, 93, 94, 97, 101, 102] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia TB |

High confidence | Included 15 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Absence or low perceived need to wear facemasks | [36, 46, 54, 62, 69, 78, 82] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza |

Moderate confidence | Included 7 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Knowledge about transmission of infectious respiratory diseases | [32, 40, 46, 49, 52, 60, 69, 78, 94] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza |

Moderate confidence | Included 9 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Financial aspects | |||||

| Food and financial insecurity limiting adherence to nonpharmaceutical measures | [32, 37, 53, 58, 60, 82, 85, 87, 88, 90–94, 98] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB |

High confidence | Included 15 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Food and financial insecurity limiting adherence to pharmacological treatment | [83, 84, 90, 91, 96, 102] | Barrier | TB | High confidence | Included 6 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Financial and social support for pharmacological treatment | [56, 83, 90, 91, 93] | Facilitator | TB | Moderate confidence | Included 5 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| Financial and social support for nonpharmaceutical measures | [32, 40, 51, 60, 80, 81, 87, 88, 98] | Facilitator | COVID-19 | Moderate confidence | Included 9 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Access to information | |||||

| Awareness about vaccination's benefits, safety and effectiveness | [35, 45, 55, 65, 69, 75, 99, 101] | Facilitator | Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis | High confidence | Included 8 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Pre-warning from healthcare providers regarding how to cope with side-effects from vaccines | [35, 44, 74, 101] | Facilitator | Influenza COVID-19 Pneumonia |

High confidence | Included 4 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Difficulties in accessing information via digital technologies | [32, 58, 64, 72, 82, 100] | Barrier | COVID-19 | High confidence | Included 6 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Campaigns for pro-vaccination in social media and television, in addition to written or visual media | [35, 44, 45, 55, 58, 73, 99, 101] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

High confidence | Included 8 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Misperceptions about vaccines' role, formulation process, testing, targets and vaccination protocols | [34, 35, 38, 42–45, 47, 48, 50, 55, 57–59, 65, 69, 71, 73, 74, 77, 79] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

Moderate confidence | Included 21 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Lack of knowledge regarding government support for getting vaccinated and misperceptions about vaccine cost | [34, 35, 55, 69, 71, 75] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

Moderate confidence | Included 6 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| Insufficient information and fake news about nonpharmaceutical measures | [32, 36, 39, 40, 46, 48, 52–54, 56, 58, 60, 62–64, 67, 69, 76, 78, 82, 85, 86, 95, 97, 100] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia TB |

Moderate confidence | Included 25 studies. Major concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Misperceptions about vaccines' effectiveness, safety and side effects | [33, 35, 38, 42, 45, 55, 57, 58, 61, 65, 70, 71, 73–75, 77, 101] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

Low confidence | Included 17 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. Minor concerns regarding coherence. |

| Lack of knowledge about vaccine availability | [34, 41, 69, 74, 77, 99] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

Low confidence | Included 6 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. Minor concerns regarding adequacy. |

| Fake news (misinformation and disinformation) about vaccines | [35, 45, 58, 77, 79] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

Low confidence | Included 5 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, coherence and adequacy. |

| Quality information released by religious leaders | [86, 99] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza |

Very low confidence | Included 2 studies. Major concerns regarding adequacy due to limited information. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Quality information on nonpharmaceutical measures on specialist websites, social media and television | [39, 98] | Facilitator | COVID-19 | Low confidence | Included 2 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| Sense of collective responsibility | |||||

| The sense of collective responsibility to protect self and others through nonpharmaceutical measures | [37, 39, 46–50, 52, 53, 56, 60, 62, 67, 68, 72, 76, 78, 80, 98] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza TB |

High confidence | Included 19 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Positive attitudes and engagement with vaccination to maintain health and protect others | [34, 35, 38, 41–43, 45, 55, 59, 69, 70, 74, 94, 99, 101] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

Moderate confidence | Included 15 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Indiscipline and lack of collective responsibility for other people | [32, 39, 40, 46, 50, 52–54, 60, 62, 63, 67, 68, 76, 81, 86, 92, 98, 100] | Barrier | COVID-19 | Moderate confidence | Included 19 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Accessibility and availability of measures | |||||

| Access barriers and conflicts of time to take the vaccination | [34, 35, 45, 55, 57, 58, 61, 70, 71, 73, 74, 79, 99] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

High confidence | Included 13 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Easily accessible locations for vaccination and pharmacological treatment | [35, 41, 61, 73, 83, 91] | Facilitator | Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis TB |

Moderate confidence | Included 6 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Need to travel to have access to pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical measures | [32, 50, 51, 84, 91, 93, 102] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB | High confidence | Included 7 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Logistical difficulties in acquiring facemasks | [32, 78] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza |

Moderate confidence | Included 2 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| The practicality of hand hygiene (handwashing and antiseptics) | [60, 69] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza |

Low confidence | Included 2 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. Minor concerns regarding coherence and adequacy. |

| The availability of facemasks | [32, 40] | Facilitator | COVID-19 | Very low confidence | Included 2 studies. Major concerns regarding methodological limitations. Moderate concerns regarding adequacy. |

| Psycho-cognitive factors | |||||

| Fear of vaccination (e.g. fear of injections, pain and side-effects) | [35, 41, 45, 50, 55, 57, 61, 71, 74, 75, 99] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

High confidence | Included 11 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Forgetting to use nonpharmaceutical measures | [46, 62, 72, 76, 78, 80, 82] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza |

High confidence | Included 7 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Fear of stigmatisation | [46, 52, 56, 58, 82–85, 87, 89–93] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB | Moderate confidence | Included 14 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence. |

| Personal beliefs against the adoption of nonpharmaceutical measures | [32, 46, 53, 54, 58, 60, 62, 69, 82, 84, 87, 89, 91–93] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza TB |

Moderate confidence | Included 15 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Individual perceptions of self-defence and self-efficacy with own health | [34, 35, 38, 43, 45, 55, 58, 65, 71, 73–75, 79, 100, 101] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

Moderate confidence | Included 15 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and coherence |

| Fatalism | [69, 70, 74] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza |

Low confidence | Included 3 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. Moderate concerns regarding adequacy. |

| Lack of social interaction and physical contact | [32, 37, 52–54, 60, 62, 63, 68, 69, 76, 82, 84, 85, 87, 92, 93, 100] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza TB |

Moderate confidence | Included 18 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Health policies | |||||

| Dissatisfaction with supportive policies, health services and professional care | [32, 53, 56, 58, 60, 66, 68, 82–85, 87–91, 93, 94] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB | High confidence | Included 18 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Dissatisfaction related to pharmacological treatment regimen and healthcare | [56, 84, 90, 91, 96, 102] | Barrier | TB | Moderate confidence | Included 6 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, adequacy and relevance. |

| Free vaccine or government financial support for vaccinating | [35, 45, 55, 70, 71, 75] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

Moderate confidence | Included 6 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| The direct or indirect warning to wear facemasks and physical distancing (e.g. social pressure, the example of other people) | [40, 46, 48, 49, 63, 68, 69, 78, 87] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza |

Moderate confidence | Included 9 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Contact tracing measures and testing | [32, 53, 72, 80] | Facilitator | COVID-19 | Low confidence | Included 4 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. Moderate concerns regarding adequacy. |

| Lack of obligation and monitoring for adherence to nonpharmaceutical measures | [39, 40, 62, 64, 67, 76, 92, 93, 95, 100] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB | Low confidence | Included 10 studies. Major concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Socio-environmental factors | |||||

| Poor sanitation conditions, access to water and housing | [32, 51, 52, 54, 60, 76, 82, 85, 87, 88, 91, 94, 95, 97, 98, 102] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB | High confidence | Included 16 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Impossibility of working from home | [37, 52, 54, 60, 62, 85, 98] | Barrier | COVID-19 | High confidence | Included 7 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Cultural differences and communication problems to follow guidelines for nonpharmaceutical measures | [39, 53, 58, 60, 64, 67, 68, 82, 87, 100] | Barrier | COVID-19 | High confidence | Included 10 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Difficulties with breathing, discomfort and social inconvenience with the use of facemasks | [36, 46, 69, 76, 78] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza |

Moderate confidence | Included 5 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Personal factors (e.g. ethnicity, anti-vaccination groups and deprived areas) | [50, 73, 94] | Barrier | COVID-19 Pertussis |

Low confidence | Included 3 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. Moderate concerns regarding adequacy. |

| Cultural differences and communication problems to vaccination | [44, 58, 59, 79, 94] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

Low confidence | Included 5 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. Moderate concerns regarding adequacy. |

| Difficulties in adopting physical distancing and self-isolation in crowded places and public transport | [37, 39, 48, 51, 53, 54, 68, 76, 95, 97] | Barrier | COVID-19 | Moderate confidence | Included 10 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Social role in the family structure and household dynamics | [52, 54, 64, 66, 68, 93] | Barrier | COVID-19 TB | High confidence | Included 6 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| Self-perception of susceptibility | |||||

| Perception of personal and environmental vulnerability | [35, 41, 45, 55, 64, 67, 68, 74, 75, 101] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

High confidence | Included 10 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. None or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Scepticism, conspiracy theories, and scientific denialism | [32, 33, 35, 38, 40, 41, 43, 46, 52–55, 58–60, 62, 65, 68, 69, 72–74, 76, 79, 82, 87, 88, 94, 95, 98–101] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

High confidence | Included 34 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Trust in authorities, health professionals and close people | |||||

| Lack of recommendations from health professionals to take the vaccine | [34, 35, 43, 44, 47, 50, 55, 57–59, 61, 65, 71, 73, 74, 77, 79, 101] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

High confidence | Included 18 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Faith and positive attitudes of engagement for adopting prevention and control measures | [32, 37, 46, 52, 53, 56, 60, 65, 68, 72, 87, 98] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pertussis TB |

High confidence | Included 12 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Recommendations from health professionals, religious leaders or family members to avoid the vaccine | [35, 41, 45, 55, 58, 71, 73, 75, 99] | Barrier | COVID-19 Influenza Pertussis Pneumonia |

High confidence | Included 9 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Previous and successful experience with vaccination | [71, 74, 77, 94] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia |

High confidence | Included 4 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations. No or very minor concerns regarding coherence, adequacy and relevance. |

| Vaccine recommendations from clinicians and encouragement by nurses, family members and friends | [34, 35, 38, 41–45, 55, 59, 61, 65, 69, 71, 73–75, 99, 101] | Facilitator | COVID-19 Influenza Pneumonia Pertussis |

Moderate confidence | Included 19 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Previous unfortunate experiences with vaccination, healthcare providers or other health services | [33, 35, 42, 59, 73, 74, 101] | Barrier | Influenza, Pneumonia Pertussis |

Moderate confidence | Included 7 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

| Encouragement of health professionals, family and friends to adhere to pharmacological treatment | [56, 89–91, 102] | Facilitator | TB | Moderate confidence | Included 5 studies. Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations and adequacy. |

| Trust in health, political and religious authorities for adopting nonpharmaceutical measures | [32, 39, 40, 46, 48, 49, 53, 60, 85, 86, 92] | Facilitator | COVID-19 | Moderate confidence | Included 11 studies. Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations. |

Objective: to identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative research evidence on the barriers to and facilitators of population adherence to prevention and control measures of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other respiratory infectious diseases. Perspective: experiences and attitudes of the population about prevention and control measures of COVID-19 and other respiratory infectious diseases. GRADE-CERQual: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research; TB: tuberculosis.

Discussion