Abstract

Background

At present, there is no objective prognostic index available for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) who underwent intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). This study is to develop a nomogram based on hematologic inflammatory indices for ESCC patients treated with IMRT.

Methods

581 patients with ESCC receiving definitive IMRT were enrolled in our retrospective study. Of which, 434 patients with treatment-naïve ESCC in Fujian Cancer Hospital were defined as the training cohort. Additional 147 newly diagnosed ESCC patients were used as the validation cohort. Independent predictors of overall survival (OS) were employed to establish a nomogram model. The predictive ability was evaluated by time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves, the concordance index (C-index), net reclassification index (NRI), and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI). Decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed to assess the clinical benefits of the nomogram model. The entire series was divided into 3 risk subgroups stratified by the total nomogram scores.

Results

Clinical TNM staging, primary gross tumor volume, chemotherapy, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio were independent predictors of OS. Nomogram was developed incorporating these factors. Compared with the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging, the C-index for 5-year OS (.627 and .629) and the AUC value of 5-year OS (.706 and .719) in the training and validation cohorts (respectively) were superior. Furthermore, the nomogram model presented higher NRI and IDI. DCA also demonstrated that the nomogram model provided greater clinical benefit. Finally, patients with <84.8, 84.8-151.4, and >151.4 points were categorized into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups. Their 5-year OS rates were 44.0%, 23.6%, and 8.9%, respectively. The C-index was .625, which was higher than the 8th AJCC staging.

Conclusions

We have developed a nomogram model that enables risk-stratification of patients with ESCC receiving definitive IMRT. Our findings may serve as a reference for personalized treatment.

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, nomogram, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, prognosis, risk-stratification

Background

Esophageal cancer ranks seventh in morbidity and sixth in mortality around the world. 1 There are two main pathological subtypes of esophageal cancer, that is, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and adenocarcinoma. ESCC accounts for 90% of cases of esophageal cancer in China. 2 According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, curative resection is the cornerstone of treatment for ESCC; however, radical chemoradiotherapy is the primary treatment for locally advanced ESCC. 3 Unfortunately, ESCC patients receiving definitive radiotherapy tend to have an unfavorable prognosis with 5-year survival rates ranging from only 25.3% to 39.2%.4,5 At present, the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) staging system is commonly utilized for prognostically evaluate patients with ESCC. However, some patients with the same clinical stage and receiving similar treatment may exhibit varying outcomes.6,7 As a result, there is a pressing need to develop a more accurate prognostic model for ESCC patients treated by definitive radiotherapy, which may help inform personalized treatment strategies.

Several nomogram models have been shown to predict the prognosis of ESCC patients treated with definitive radiotherapy. In a study by Zhang et al, 8 C-reactive protein/albumin (CRP/Alb) ratio was found to be an independent predictor of OS in patients with thoracic ESCC undergoing standard definitive radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Furthermore, a nomogram incorporating the CRP/Alb ratio effectively predicted the OS, and showed greater potential for clinical benefit than the AJCC staging system. In 2020, Xu et al 9 reported a significant correlation of pretreatment lymphopenia with OS of ESCC patients undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy. Furthermore, the nomogram model that incorporated pretreatment absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) exhibited good concordance with actual 3-year overall survival (OS) probability. Recently, hematologic inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have shown remarkable association with the prognosis of ESCC.10,11 In a recent study, pretreatment NLR was found to be a prognostic factor for long-term survival of patients with ESCC undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy. 7 Moreover, a nomogram model that incorporated pretreatment NLR showed greater predictive accuracy than the AJCC staging system.

However, the current nomogram model based on hematologic inflammatory indices has certain limitations for patients with ESCC receiving definitive radiotherapy. First, previous prognostic nomogram models either did not incorporate or only incorporate a single inflammatory biomarker.7-9 Hence, further exploration of the prognostic value of more inflammatory indicators in ESCC patients treated with definitive radiotherapy is a key imperative. Second, previous studies have mainly assessed the discriminative ability of the nomogram model through the consistency index (C-index) and the area under subject operating characteristic curve (AUC).12,13 Net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) have infrequently been used to compare the predictive performance of the nomogram model and the staging system.14,15 Taken together, these studies underscore the need to generate a novel nomogram for a more accurate prediction of the outcomes of ESCC patients undergoing definitive radiotherapy.

The objective of the study was to develop a nomogram model to facilitate more accurate risk-stratification of ESCC patients receiving definitive radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Our findings may contribute to more dependable prognostic prediction and personalized treatment for these patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fujian Cancer Hospital (No. K2021-129-01). The study followed relevant Equator guidelines. The reporting of this study conformed to STROBE guidelines. 16 Each patient provided written informed consent before treatment, and the information was anonymized before analysis. Patients were grouped in the study based on the consistency of their diagnosis across different years.17,18 A total of 581 patients with ESCC receiving definitive IMRT were enrolled in our retrospective study. Of which, 434 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed ESCC between January 2012 and December 2016 were enrolled into the primary series of this clinical study, which was defined as the training cohort. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) patients with a histological or cytological diagnosis of ESCC; (2) definitive intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with or without chemotherapy; and (3) availability of complete pretreatment clinical and laboratory data. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with any other primary malignancy and (2) patients who received conventional radiotherapy. Of which, 147 patients who were screened using the above criteria from January 2008 to December 2011 was taken as the validation set.

As explained in our previously published study, two experienced thoracic radiation oncologists plotted primary gross tumor volume (GTVp) from pretreatment chest computed tomography (CT) images. 19 Clinical TNM staging was performed according to the eighth edition of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) staging criteria for esophageal cancer.

Peripheral Blood Differential Cell Counts and the Related Indices

As part of routine clinical workup, the baseline neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, and monocyte counts were obtained before definitive radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was defined as neutrophil count divided by lymphocyte count. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) was calculated as lymphocyte count divided by the monocyte count. Platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) was calculated as platelet count divided by lymphocyte count. To transform continuous variables (including NLR, LMR, and PLR) into categorical variables, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to identify threshold values for survival using the area under the curve. The optimal cut-off values of NLR, LMR, and PLR were 2.0, 3.0, and 160, respectively.

Treatment and Follow-Up

All patients in the present study were treated with definitive IMRT. The median dose was 61.50 Gy (range, 40-70 Gy) (dose per fraction: 1.8-2.1 Gy). The contents of IMRT, as described in our previous study, include the total volume of the clinical target volume and primary tumor (GTVp), organs at risk (OAR) of radiotherapy, the target dose and dose limit of OAR. 20 415 (71.4%) of 581 patients received chemotherapy including platinum- or taxane-based regimens with a median of 2 cycles.

The patient follow-up schedule was described in our previous study. In brief, follow-up assessments were conducted every 3 months during the first 2 years following definitive IMRT, every 6 months between years 3 and 5, and annually thereafter. The primary endpoint of the study was OS, which was defined as the period from the date of histological diagnosis to the date of death due to any cause or last follow-up. The last follow-up was conducted in October 2021.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistical software version 26.0 and R version 9.0.0 (http://www.r-project.org). ROC curve was used to determine the optimal threshold of continuous parameters for predicting survival based on the Youden index. The OS rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and between-group differences were assessed using the log-rank test. To identify independent prognostic factors for OS, univariate and multivariate analyses of baseline indicators were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression.

Subsequently, a prognostic nomogram model based on these independent predictors was established to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS. The discriminative ability of the nomogram model was evaluated by the C-index and the AUC of the ROC curve. The C-index was corrected by 1000 resampling bootstrap. The accuracy of the nomogram model was verified by plotting a calibration curve, which was a comparison of the nomogram-predicted survival probability and actually observed survival outcome. Furthermore, NRI and IDI were calculated to assess the degree of predictive performance optimization by comparing the nomogram model with the 8th AJCC staging. Decision curve analysis (DCA), based on net benefits, was applied to measure clinical usefulness of the nomogram model. Finally, based on the total scores calculated by the nomogram, the entire study population (including the training and validation cohort) was divided into 3 risk groups (low-, intermediate-, and high-risk) using X-tile software (http://www.tissuearray.org/rimmlab/). Statistical significance was set at a two-sided P value <.05.

Results

Clinical Characteristics and Survival

The baseline clinical characteristics of 581 patients in the whole cohort are summarized in Table 1. There were more males than females (ratio, 2.40:1) and the median age of patients was 65 years (range, 41-91). 37.8% patients were aged ≥70 years. In 51.9% of all patients, the primary tumor was located in the middle esophagus. Most patients were staged as locally advanced. The threshold value of GTVp and tumor length were retrospectively defined as 30 cm3 and 5 cm, respectively, in our previous studies.20,21

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Inflammatory Indicators of Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

| Whole cohort (n = 581) | Training cohort (n = 434) | Validation cohort (n = 147) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 410 (70.6) | 303 (69.8) | 107 (72.8) |

| Female | 171 (29.4) | 131 (30.2) | 40 (27.2) |

| Age (years) | |||

| <70 | 361 (62.2) | 268 (61.9) | 93 (63.3) |

| ≥70 | 219 (37.8) | 165 (38.1) | 54 (36.7) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Cervical | 50 (8.6) | 40 (9.2) | 10 (6.8) |

| Upper thoracic | 172 (29.6) | 137 (31.6) | 35 (23.8) |

| Middle thoracic | 300 (51.6) | 215 (49.5) | 85 (57.8) |

| Lower thoracic | 56 (9.6) | 39 (9.0) | 17 (11.6) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | |

| Clinical T stage | |||

| T1 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| T2 | 45 (7.7) | 22 (5.1) | 23 (15.6) |

| T3 | 186 (32.0) | 125 (28.8) | 61 (41.5) |

| T4 | 349 (60.1) | 286 (65.9) | 63 (42.9) |

| Clinical N stage | |||

| N0 | 167 (28.7) | 120 (27.6) | 47 (32.0) |

| N1 | 218 (37.5) | 162 (37.3) | 56 (38.1) |

| N2 | 168 (28.9) | 128 (29.5) | 40 (27.2) |

| N3 | 28 (4.8) | 24 (5.5) | 4 (2.7) |

| Clinical M stage | |||

| No | 467 (80.4) | 350 (80.6) | 117 (79.6) |

| Yes | 114 (19.6) | 84 (19.4) | 30 (20.4) |

| 8th AJCC stage | |||

| II | 85 (14.6) | 55 (12.7) | 30 (20.4) |

| III | 126 (21.7) | 76 (17.5) | 50 (34.0) |

| IVA | 256 (44.1) | 219 (50.5) | 37 (25.2) |

| IVB | 114 (19.6) | 84 (19.4) | 30 (20.4) |

| GTVp (cm3) | |||

| <30 | 231 (39.8) | 179 (41.2) | 52 (35.4) |

| ≥30 | 350 (60.2) | 255 (58.8) | 95 (64.6) |

| Tumor length (cm) | |||

| ≤5 | 321 (55.2) | 247 (56.9) | 74 (50.3) |

| >5 | 260 (44.8) | 187 (43.1) | 73 (49.7) |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| No | 166 (28.6) | 120 (27.6) | 46 (31.3) |

| Yes | 415 (71.4) | 314 (72.4) | 101 (68.7) |

| NLR | |||

| ≤2.0 | 254 (43.7) | 191 (44.0) | 63 (42.9) |

| >2.0 | 327 (56.3) | 243 (56.0) | 84 (57.1) |

| LMR | |||

| <3.0 | 158 (27.2) | 110 (25.3) | 48 (32.7) |

| ≥3.0 | 423 (72.8) | 324 (74.7) | 99 (67.3) |

| PLR | |||

| <160.0 | 417 (71.8) | 314 (72.4) | 103 (70.1) |

| ≥160.0 | 164 (28.2) | 120 (27.6) | 44 (29.9) |

Abbreviations: GTVp, primary gross tumor volume; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; LMR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

In the training cohort, 340 (21.7%) patients had died and the median survival was 21.8 months (range, 1.6-117.3). In the validation cohort, 127 (13.6%) patients had died and the median survival was 20.8 months (range, 2.2-164.4). The 5-year OS rate for the entire cohort was 26.0% (26.7% in the training cohort and 23.8% in the validation cohort).

Nomogram Model Construction and Validation

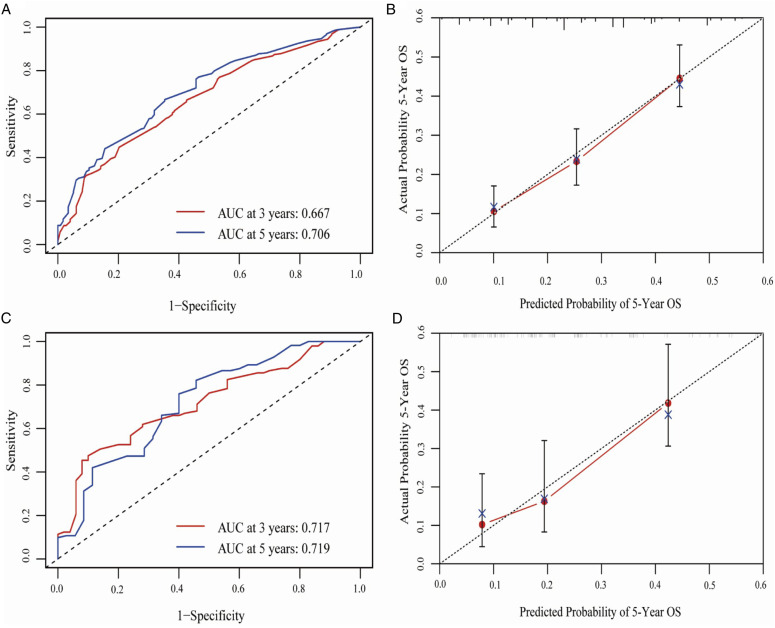

On univariate analyses, age, tumor location, clinical T stage (cT), clinical N stage (cN), cTNM, GTVp, chemotherapy (CT), NLR, LMR, and PLR were identified as prognostic factors for the training cohort. Taking these factors including cTNM, GTVp, chemotherapy (CT), NLR, LMR, and PLR into multivariate analyses, it was found that cTNM, GTVp, CT, NLR, and PLR were independent predictors of prognosis (Table 2). Based on the above independent prognostic factors, a nomogram model was developed to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates (Figure 1). First, internal validation was performed to assess the predictive ability of the nomogram model in the training cohort. The discriminative ability of the nomogram model was evaluated by calculating the C-index. The C-index for 5-year OS was 0.627 (95% CI: 0.597-0.658) (Table 3), and the AUC value of the ROC curve for 5-year OS was 0.706 (95% CI: 0.653-0.760) (Figure 2A). The calibration curve for 5-year OS showed that the observed clinical outcomes were in consistent with the predicted outcomes (Figure 2B).

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis for Overall Survival in Training Cohort.

| HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8th AJCC stage | 1.372 | 1.205-1.562 | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.625 | 0.492-0.794 | <0.001 |

| GTVp | 1.543 | 1.231-1.935 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 1.328 | 1.041-1.693 | 0.022 |

| PLR | 1.473 | 1.147-1.892 | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CI, confidence interval; GTVp, primary gross tumor volume; HR, hazard ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Figure 1.

Nomogram model for prediction of 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS) in ESCC patients in the training cohort.

Table 3.

Discriminatory Ability of the Nomogram Model Compared to AJCC Stage.

| C-index (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | NRI (P value) | IDI (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | 0.627 | 0.706 | - | - |

| Nomogram | (0.597-0.658) | (0.653-0.760) | ||

| TC | 0.567 | 0.605 | - | - |

| AJCC stage | (0.578-0.656) | (0.550-0.660) | ||

| VC | 0.629 | 0.719 | - | - |

| Nomogram | (0.578-0.676) | (0.618-0.620) | ||

| VC | 0.605 | 0.662 | - | - |

| AJCC stage | (0.576-0.678) | (0.557-0.767) | ||

| TC nomogram | - | - | 0.309 | 0.08 |

| vs. AJCC stage | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | ||

| VC nomogram | - | - | 0.171 | 0.055 |

| vs. AJCC stage | P = 0.01 | P = 0.01 |

Abbreviation: TC, training cohort; VC, validation cohort; C-index, concordance index; CI, confidence interval; NRI, net reclassification index; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement.

Figure 2.

A. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves by nomogram for 3-year and 5-year OS in the primary cohort (PC) (red line: 3-year OS; blue line: 5-year OS); B. Calibration curve for 5-year OS prediction according to the PC nomogram; C. ROC curves by nomogram for 3-year and 5-year OS validation cohort (VC) (red line: 3-year OS; blue line: 5-year OS); D. Calibration curve for predicting 5-year OS according to the VC nomogram.

Finally, the predictive ability of the constructed nomogram model was assessed in the validation cohort. The C-index for 5-year OS was 0.629 (95% CI: 0.578-0.676) and the 5-year AUC value was 0.719 (95% CI: 0.605-0.833) in the validation cohort, which were superior to those for the training cohort (Figure 2C). The calibration curve of 5-year OS exhibited favorable consistency between predicted and observed outcomes (Figure 2D).

Comparing the Predictive Accuracy of the Nomogram and the 8th AJCC Staging

As presented in Table 3, the C-index for the nomogram model was higher than the AJCC staging in both the training cohort (0.627 vs 0.567) and the validation cohort (0.629 vs 0.605). In addition, the time-dependent ROC analysis revealed that the AUC of the nomogram model was superior to that of the AJCC staging in both the training cohort (0.706 vs 0.605) and the validation cohort (0.719 vs 0.662).

In terms of the improvement in predictive performance, the NRI of the nomogram model increased by 30.9% and 17.1% in the training and validation cohorts, respectively (all P < 0.05). Furthermore, the IDI of the nomogram model increased by 8.0% and 5.5% in the training and validation cohorts, respectively (all P < 0.05). Finally, using DCA as a novel method to assess clinical usefulness, the net clinical benefit of the nomogram model was suggested to be greater compared to the 8th AJCC staging, as demonstrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Decision curve analysis of the nomogram (blue line), the AJCC stage (red line),and GTVp (green line) for 5-year OS in the primary cohort (PC).

Risk-Groups Categorization

According to the total points of nomogram, all patients were divided into 3 risk subgroups using the X-tile software (Figure 4). Of these patients, those with <84.8 points were classified as low-risk group (28.6%), those with 84.8-151.4 points were classified as intermediate-risk group (48.2%), and those with>151.4 points were classified as high-risk group (23.2%). The 5-year OS rates in the 3 risk groups were 44.0%, 23.6%, and 8.9%, respectively (Figure 4A). The C-index was 0.625 (95% CI: 0.599-0.651), as shown in Table 1. In contrast, using the 8th AJCC staging, the whole cohort was divided into stage II, stage III, stage IVA, stage IVB, with 14.6%, 21.7%, 44.1%, and 19.6% of patients in each group, respectively. The 5-year OS rates in these groups were 47.1%, 23.8%, 25.4%, and 14.0%, respectively (Figure 4B). The C-index was 0.574 (95% CI: 0.549-0.600) (Table 1). The results demonstrated markedly better discrimination ability of the nomogram model in terms of C-index (P < .001).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival (OS) curves for A. groups disaggregated by the AJCC staging and B. risk group based on the nomogram model in the entire cohort.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the current study represents a novel research that successfully constructed a prognostic nomogram model and risk-stratification system incorporating multiple hematologic inflammatory indices for patients with ESCC receiving definitive IMRT based on a large cohort. In this study, cTNM, GTVp, chemotherapy (CT), NLR, and PLR were identified as independent prognostic indicators by multivariate Cox regression analysis in the training cohort. A nomogram was developed based on these 5 independent factors to predict OS, and verified in the validation cohort as well. The nomogram model was found to be better than the AJCC staging in predicting OS and clinical survival benefits. Finally, the entire cohort was stratified into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk subgroups based on the nomogram total scores, which demonstrated superior predictive power for OS compared to the AJCC clinical staging system. Taken together, these results suggest that the nomogram model is a valuable tool for risk-stratification and survival prediction in patients with ESCC treated with radical IMRT.

In this study, several hematological inflammatory indices including NLR and PLR were found to independently impact the prognosis besides other common factors, such as cTNM, GTVp, and chemotherapy (CT). Of note, several studies have demonstrated a close correlation of NLR and PLR with prognosis of patients with several other kinds of malignancies including gastric cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and colorectal carcinoma.22-24 Moreover, some studies have also demonstrated a significant association of pretreatment elevated PLR and NLR with poorer prognosis and deeper tumor invasive depth in patients with ESCC.25,26 This phenomenon could be attributed to the potential involvement of systemic inflammatory response in the migration, invasion, and metastasis of malignant cells in various tumors, including ESCC. 27 Therefore, the incorporation of NLR and PLR into the nomogram model may help improve the prognostic assessment of patients with ESCC receiving definitive IMRT.

We evaluated the predictive performance of the nomogram model using a variety of indices, including accuracy, discrimination ability, and clinical validity. Calibration, which is commonly used method for assessing the accuracy of nomogram, refers to the agreement between the predicted probabilities and the actual probabilities of an event or outcome. 28 In this study, the calibration curves between the OS predicted by nomogram and the actual OS showed a good agreement in both the training and validation cohorts. In addition, the C-index and the ROC curve are most commonly used to assess the discrimination of the nomogram model. 29 In the training cohort, the C-index and AUC values for 5-year OS were .627 and .706, respectively, showing good differentiation and predictive ability for OS. Moreover, the C-index and AUC values for 5-year OS were .629 and .719 in the validation cohort, respectively, confirming the reproducibility and stability of the nomogram model. Hence, the constructed nomogram model demonstrated a good predictive performance. Compared to the prognostic models used in previous research, our nomogram model was more accurate because it was based on patients who underwent definitive IMRT, which may mitigate the survival differences caused by varying radiotherapy methods.7,8,30

To further compare the predictive ability of the nomogram model with that of the AJCC staging, 4 evaluation indicators including AUC, C-index, NRI, and IDI were employed. AUC value and C-index were used as the basic reference indicators to estimate the improvement of predictive performance of the nomogram model as compared to the AJCC staging. 29 In our study, the AUC values and C-index of the nomogram in the training and validation cohorts were superior to those of the AJCC staging. In recent years, NRI and IDI have been widely recommended for evaluating and comparing the distinctive ability between the two prediction models. 14 NRI was originally applied for quantitative evaluation of the improvement in classification performance of the new model compared to the original model, whereas IDI was employed to assess the changes in risk differentials. 29 In our study, the NRI and IDI of the AJCC staging were significantly inferior to those of the nomogram, suggesting better predictive ability of the nomogram model for OS. In contrast, prior studies of patients with ESCC treated with definitive radiotherapy did not employ net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) to evaluate the prognostic discrimination ability of the nomogram model.7,8,30

DCA was developed to determine whether the use of predictive models in clinical decision-making has a net benefit, and to assess the clinical applicability of such models. 31 In our study, the nomogram offered a higher net benefit than the AJCC staging at any given threshold, indicating a better clinical application value of the constructed nomogram. It is noteworthy that the clinical net benefit of GTVp was almost the same as that of the clinical AJCC staging. GTVp has been shown to be an independent predictor of survival in patients with ESCC treated with definitive radiotherapy.19,32 A larger GTVp typically indicates a greater tumor load and a higher radioresistant hypoxic cells and clonogenic cells, resulting in poorer survival rates. 32 This explains the markedly superior net benefit of the nomogram incorporating hematological inflammatory indices, GTVp, cTNM, and CT compared to the AJCC staging.

Finally, risk-stratification system was established based on the total nomogram scores using the X-tile software. In the study population, 28.6%, 48.2%, and 23.2% of patients were categorized into low-, moderate-, and high-risk subgroups, whereas the proportion of patients in AJCC stages II, III, IVA, and IVB were 14.6%, 21.7%, 44.1%, and 19.6%, respectively. This indicated a more balanced patient distribution among the 3 risk subgroups as compared to that among the clinical AJCC stage. Moreover, this risk-stratification showed a significantly higher C-index than the clinical AJCC stage, indicating that the nomogram had better discrimination ability for risk-stratification. Compared to previous studies on nomogram models for ESCC receiving definitive radiotherapy, our research provided clear stratification based on risk levels identified by the model, enabling clinicians to develop more effective and reasonable treatment strategies.7,8,30 Patients in the high-risk group may require more intensive therapies: (1) adjuvant chemotherapy; (2) targeted drugs 33 ; or (3) immunotherapy. In particular, immunotherapy has rapidly developed in recent years and has been actively explored and applied in the treatment of patients with ESCC.34,35 Studies have demonstrated that the combination of immunotherapy and radiotherapy can synergistically promote anti-tumor activity in vitro, thus effectively controlling local lesions and distant micrometastases.36,37 Therefore, radiotherapy plus immunotherapy may improve the treatment efficacy for high-risk ESCC patients. In addition, for patients in the low-risk group, reducing the radiation dose or chemotherapy cycles may be appropriate to decrease both the side effects of radiotherapy combined with adjuvant chemotherapy and the treatment cost.

However, our study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, we did not analyze all inflammatory parameters, as some inflammatory mediators such as procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor were not routinely examined at our institution. In addition, this was a retrospective, single-center study and our results may have been affected by potential confounding factors. Further prospective, multicenter studies are required to verify the precision of the nomogram model. Finally, we did not evaluate the dynamic changes in hematological indicators before and after treatment, which may enhance the prognostic capability of the nomogram and refine risk-stratification of patients.

Conclusions

We have successfully established a nomogram utilizing pretreatment inflammatory indices for predicting OS, and developed a risk-stratification system for ESCC patients receiving IMRT, which was superior to the AJCC staging. Our study may serve as a valuable clinical reference for prognostic prediction and individualized treatment.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our patients and staff members who participated in the patient care to make this project available. We thank Medjaden Inc. for scientific English editing of this manuscript.

Appendix.

Abbreviations

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- IMRT

Intensity-modulated radiotherapy

- OS

Overall survival

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the curve

- C-index

Concordance statistics

- NRI

Net reclassification index

- IDI

Integrated discrimination improvement

- DCA

Decision curve analysis

- GTVp

Primary gross tumor volume

- CT

Chemotherapy

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- PLR

Platelet lymphocyte ratio

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- UICC/AJCC

Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CRP/Alb

Reactive protein/albumin ratio

- ALC

Absolute lymphocyte count

- LMR

Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

- CI

Confidence level

- HR

Hazard ratio

- TC

Training cohort

- VC

Validation cohort

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: YX and JC participated in the design of the study. ZX and HK performed the experiments and the statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript, and assisted with the manuscript preparation. BZ, CL, YZ, and LW drafted the manuscript and helped with the manuscript preparation. YL, YY, LC, and MY assisted with experiments performance and statistical analysis. YX examined and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

he author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: U21A20377), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (#2023J01178, #2021J01428), Fujian Provincial Clinical Research Center for Cancer Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy (Grant number: 2020Y2012), and the National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Program.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the lack of consent from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s) for publication statement. However, interested parties may obtain the datasets from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study is a retrospective observational study and was conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines, regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The methods and procedures for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fujian Cancer Hospital (No. K2021-129-01).

Consent: Each patient provided written informed consent before treatment, and the information was anonymized before analysis. Consecutive patients with new diagnoses of ESCC and treated in Fujian Cancer Hospital from January 2008 to December 2016 were retrospectively reviewed.

ORCID iD

Hongqian Ke https://orcid.org/0009-0003-4625-7573

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth EC, Lagergren J, Fitzgerald RC, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, et al. Esophageal and Esophagogastric junction cancers, Version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(7):855-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Zhou L, Yang Y, Yang L, Chen L. Clinical effect of radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy for non-surgical treatment of the Esophageal Squamous cell Carcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:4183-4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan XW, Wang HB, Mao JF, Li L, Wu KL. Sequential boost of intensity-modulated radiotherapy with chemotherapy for inoperable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A prospective phase II study. Cancer Med. 2020;9(8):2812-2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng W, Zhang W, Yang J, et al. Nomogram to predict overall survival for thoracic esophageal Squamous cell Carcinoma patients after radical Esophagectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(9):2890-2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang P, Yang M, Wang X, Zhao Z, Li M, Yu J. A nomogram for the predicting of survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(3):233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Guo XW, Yin XX, Liu YC, Ji SJ. Nomogram-integrated C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts efficacy and prognosis in patients with Thoracic Esophageal Squamous cell Carcinoma receiving Chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:9459-9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu H, Lin M, Hu Y, et al. Lymphopenia during definitive Chemoradiotherapy in Esophageal Squamous cell Carcinoma: Association with dosimetric parameters and patient outcomes. Oncol. 2021;26(3):e425-e434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishibashi Y, Tsujimoto H, Sugasawa H, et al. Prognostic value of platelet-related measures for overall survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;164:103427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishibashi Y, Tsujimoto H, Yaguchi Y, Kishi Y, Ueno H. Prognostic significance of systemic inflammatory markers in esophageal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020;4(1):56-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obuchowski N. A. Receiver operating characteristic curves and their use in radiology[J]. Radiology 2003;229(1):3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lirette ST, Aban I. Quantifying predictive accuracy in survival models. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24(6):1998-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambless LE, Cummiskey CP, Cui G. Several methods to assess improvement in risk prediction models: Extension to survival analysis. Stat Med. 2011;30(1):22-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leening MJ, Steyerberg EW, Van Calster B, D'Agostino RB, Pencina MJ. Net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement require calibrated models: relevance from a marker and model perspective. Stat Med. 2014;33(19):3415-3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mo H, Li P, Jiang S. A novel nomogram based on cardia invasion and chemotherapy to predict postoperative overall survival of gastric cancer patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19(1):256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fei Z, Qiu X, Li M, Chen C, Li Y, Huang Y. Prognosis viewing for nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy: Application of nomogram and decision curve analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50(2):159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Lin Y, Cai W, et al. A new clinical staging system for esophageal cancer to predict survival after definitive chemoradiation or radiotherapy. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M, Li X, Chen Y, et al. Proposed revision of the 8th edition AJCC clinical staging system for esophageal squamous cell cancer treated with definitive chemo-IMRT based on CT imaging. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Huang Q, Chen J, et al. Primary gross tumor volume is prognostic and suggests treatment in upper esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Zhao W, Yu Y, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in gastric cancer: An updated meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18(1):191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diem S, Schmid S, Krapf M, et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;111:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, et al. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A glasgow inflammation outcome study. Eur J Cancer 2011, 47(17):2633-2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: Experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(1):218-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin PC, Harrell FE, van Klaveren D. Graphical calibration curves and the integrated calibration index (ICI) for survival models. Stat Med. 2020;39(21):2714-2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):128-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Yu Y, Wu H, et al. A novel model combining tumor length, tumor thickness, TNM_Stage, nutritional index, and inflammatory index might be Superior to the 8th TNM staging criteria in predicting the prognosis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma patients treated with definitive Chemoradiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:896788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickers AJ, Holland F. Decision curve analysis to evaluate the clinical benefit of prediction models. Spine J. 2021;21(10):1643-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen CZ, Chen JZ, Li DR, et al. Long-term outcomes and prognostic factors for patients with esophageal cancer following radiotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(10):1639-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato K, Ura T, Koizumi W, et al. Nimotuzumab combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in Japanese patients with esophageal cancer: A phase I study. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(3):785-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Wang P, Pang Q. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A narrative review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(18):1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mimura K, Yamada L, Ujiie D, et al. Immunotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a review. Fukushima J Med Sci 2018;64(2):46-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bando H, Kotani D, Tsushima T, et al. TENERGY: Multicenter phase II study of Atezolizumab monotherapy following definitive Chemoradiotherapy with 5-FU plus Cisplatin in patients with unresectable locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao XY, Liu CY, He JF, Wang LS, Zhang T. Combination of checkpoint inhibitors with radiotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treatment: A novel strategy. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(5):5011-5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]