Abstract

Approximately 10–30% of individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exhibit a dissociative subtype of the condition defined by symptoms of depersonalization and derealization. This study examined the psychometric evidence for the dissociative subtype of PTSD in a sample of young, primarily male post-9/11-era Veterans (n = 374 at baseline and n = 163 at follow-up) and evaluated its biological correlates with respect to resting state functional connectivity (default mode network; DMN; n = 275), brain morphology (hippocampal subfield volume and cortical thickness; n = 280), neurocognitive functioning (n = 337), and genetic variation (n = 193). Multivariate analyses of PTSD and dissociation items suggested a class structure was superior to dimensional and hybrid ones, with 7.5% of the sample comprising the dissociative class; this group showed stability over 1.5 years. Covarying for age, sex, and PTSD severity, linear regression models revealed that derealization/depersonalization severity was associated with: decreased DMN connectivity between bilateral posterior cingulate cortex and right isthmus (p = .015; adjusted-p [padj] = .097); increased bilateral whole hippocampal, hippocampal head, and molecular layer head volume (p = .010 - .034; padj = .032 - .053); worse self-monitoring (p = .018; padj = .079); and a candidate genetic variant (rs263232) in the adenylyl cyclase 8 gene (p = .026), previously associated with dissociation. Results converged on biological structures and systems implicated in sensory integration, the neural representation of spatial awareness, and stress-related spatial learning and memory, suggesting possible mechanisms underlying the dissociative subtype of PTSD.

Keywords: dissociative subtype of PTSD, genotype, MRI, default mode network, hippocampus, neuropsychological functioning

General Scientific Summary:

This study evaluated biological correlates of the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder among trauma-exposed Veterans. The study identified several neuroimaging and genetic biomarkers that were differentially associated with symptoms of derealization and depersonalization relative to posttraumatic stress disorder. These biomarkers have relevance for sensory integration, spatial awareness, and memory, suggesting that alterations in these basic processes may underlie the clinical manifestations of the dissociative subtype of PTSD.

The concepts of dissociation and psychological trauma have been linked for more than a century, dating to the seminal writing of Pierre Janet (1889). Until the publication of the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), dissociative symptoms that occurred in the context of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were reflected in just two core symptoms of the disorder: dissociative flashbacks and psychogenic amnesia. Though controversial, the conceptualization of the relationship between dissociation and PTSD shifted in DSM-5 with the inclusion of a new dissociative subtype of PTSD as defined by meeting full criteria for PTSD and also exhibiting “persistent or recurrent” (APA, 2013, p. 274) symptoms of derealization (perceiving the world as unreal) and/or depersonalization (perceiving one’s self as unreal). A substantial body of research has provided evidence for this subtype configuration and suggested that the subtype represents roughly 10–30% of the PTSD population (e.g., Wolf, Miller et al., 2012; Frewen et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2013), though this may be greater in clinics providing inpatient care (Hill et al., 2020). A recent meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of the dissociative subtype per latent class or latent profile analysis (LCA and LPA, respectively) was 22.8% (White et al., 2022). To date, at least 18 published studies (Table S1) employing LCA/LPA of measures of PTSD and dissociative symptoms have found evidence for this unique subgroup. These studies have encompassed a range of populations including male and female Veterans (Wolf, Miller et al., 2012; Wolf, Lunney et al., 2012), adolescents (Choi et al., 2017), sexual abuse survivors (Armour, Elklit et al., 2014), community samples (Műllerová et al., 2016), college students (Blevins et al., 2014), as well as globally distributed cohorts (Armour, Karstoft et al., 2014; Ross et al., 2018; Armour, Elklit et al., 2014; see also: Stein et al. 20131, and Kim et al., 20192). Collectively, this body of research suggests that individuals with the subtype tend to report more sexual trauma (Gidzgier et al., 2019; Wolf, Miller et al., 2012; Frewen et al., 2015; Guetta et al., 2019) and have a higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities (Kim et al., 2019; Gidzgier et al., 2019; Wolf, Lunney et al., 2012; Armour, Elklit et al., 2014).

The nature of the dissociative subtype of PTSD differs from other psychiatric diagnoses with established types or subtypes in that the dissociative subtype is not defined by variation in the core symptoms of PTSD (as is the case, for example, with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, in which the inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, and combined types differ according to the prominence of core symptoms of the disorder). Rather, the dissociative subtype is defined by meeting full criteria for PTSD plus additional comorbid dissociative symptoms (APA, 2013). Dissociative symptoms can also occur outside the context of PTSD (e.g., dissociative identity disorder; DID), with dissociative disorders represented in their own chapter of the DSM-5. This poses an added challenge in correctly diagnosing dissociation that occurs in the context of PTSD. Thus, it is important to attempt to distinguish biomarkers of the core features of PTSD from those specific to the subtype. Doing so may help to validate the subtype as a unique manifestation of PTSD and point towards biological mechanisms underlying its symptoms, thereby informing identification and treatment efforts.

Though the dissociative subtype of PTSD has been shown to be psychometrically replicable, to our knowledge, the class structure it is predicated on has not been empirically compared to dimensional and hybrid (class + dimension) models, nor has the longitudinal stability of the subtype been established. It remains unclear to what extent this typology relates to differential risk factors, clinical course, treatment response, genetic variation, and/or neurobiology. A few studies have provided preliminary evidence that the dissociative subtype may be associated with differential response to PTSD psychotherapy (Wolf et al. 2016, Resick et al., 2012; Cloitre et al., 2012) or pharmacotherapy (Burton et al., 2018), though others have found no evidence that the subtype moderates PTSD treatment efficacy (Zoet et al., 2018; Haagen et al., 2018). As detailed below, there is also mixed evidence for biomarkers of the subtype that are distinct from that of PTSD.

Functional Connectivity

The majority of functional brain imaging research concerning the dissociative subtype of PTSD comes from resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) work. Resting state research aims to map neural networks that are defined by the real time correlation of spontaneous (not task driven) blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) signals (an index of brain activation) across brain regions when an individual is at rest. This contrasts with task-based functional MRI which is designed to elicit a symptom or cognitive response via a controlled paradigm and then determine the brain region underlying it.

The default mode network (DMN) is perhaps the most well studied resting state network in PTSD research. It is also of particular interest for the study of dissociation because it reflects coordinated activation of the brain across many regions while an individual is at rest and not attending to external stimuli (Mason et al., 2007). DMN is activated during internally focused experiences, such as mind-wandering, rumination, self-referential thinking, and autobiographical memories, including processing of emotion relating to personal experiences (Mason et al., 2007; Satpute & Lindquist, 2019; Smallwood et al., 2021). The activity of the DMN is attenuated when an individual attends to salient stimuli or engages in goal-focused behavior (Raichle et al., 2001). The DMN involves the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) as its main hub and several strongly correlated regions, including the anterior medial prefrontal cortex, dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, ventral medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), temporal lobe, and lateral parietal cortex (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2010). Studies focused on neuroimaging of PTSD (without separation of dissociative symptoms) have suggested the disorder is associated with decreased DMN and increased salience network connectivity (activated when responding to external stimuli; Koch et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2017). Given that dissociative symptoms reflect a failure to attend to and integrate sensory information into consciousness and a tendency to be lost in internal experiences (Spiegel, 1997), it is possible that those with the dissociative subtype of PTSD may show altered DMN activity. Broadly consistent with this, one study analyzed subject-level connectivity matrices and reported global network connectivity differences in association with dissociative symptoms, particularly in regions associated with the executive control and default mode networks (Lebois et al., 2021). However, no study has specifically quantified the DMN in association with the dissociative subtype using functional MRI.

Prior functional connectivity studies of the dissociative subtype have focused on associations between a variety of brain regions that may underpin the subtype, but are not specific to the DMN. Lanius and colleagues (2010, 2012) proposed that the dissociative subtype is defined by enhanced activation of frontal cortical activity that serves to inhibit or “overmodulate” the reactive, emotional limbic brain (e.g., hippocampus and amygdala). This contrasts with theory and evidence that PTSD is generally associated with greater (unrestrained) activity in limbic regions (Lanius et al., 2010, 2012). For example, resting state studies comparing individuals with the dissociative subtype to those with PTSD without dissociation have found that those in the subtype group evidenced decreased amygdala and limbic region resting state activation (Nicholson et al., 2019), increased resting state activation in frontal regions (Nicholson et al., 2019), increased connectivity between amygdala subregions and frontal and parietal cortical areas (Nicholson et al., 2015), and increased connectivity between insula subregions and the basolateral amygdala subregion (Nicholson et al., 2016). Consistent with this, dynamic causal modeling of resting state connectivity data suggested that connections between frontal (vmPFC) and amygdala subregions and the periaqueductal gray were primarily directed from cortical to subcortical areas for those with the dissociative subtype compared to those with PTSD alone (Nicholson et al., 2017). Depersonalization and derealization symptom severity have also been shown to correlate with connectivity between the insula and the basolateral amygdala (Nicholson et al., 2016).

However, mixed findings have also raised questions about some of the conclusions that have been drawn to date. For example, a recent study found that individuals in the dissociative subtype group showed a pattern of decreased resting state connectivity between the bilateral basal forebrain and the extended amygdala relative to those with PTSD alone (Olivé, et al., 2021), which is inconsistent with the prefrontal overmodulation hypothesis. There is also doubt about the specificity of prefrontal to limbic region connectivity as a marker for the subtype, as differential functional connectivity within a broad range of other cortical and subcortical regions has also been reported (Table S2).

Brain Morphology

Neuroimaging research focused on brain morphology among individuals diagnosed with PTSD has tended to identify structural differences in prefrontal and hippocampal regions. For example, the volume of the anterior cingulate cortex, which is critical for emotion regulation (Etkin et al., 2011), has been shown to be smaller among individuals with PTSD (Kühn & Gallinat, 2013; Woodward et al., 2006) as has the vmPFC, and middle temporal gyrus (Kühn & Gallinat, 2013), when compared to trauma-exposed controls. Reduced cortical thickness in prefrontal regions (Wrocklage et al., 2017) and the fusiform gyrus (Clausen et al., 2020) has also been reported among PTSD cohorts compared to combat-exposed individuals without PTSD. A meta-analysis found that individuals with PTSD tended to have smaller hippocampal volume relative to trauma-exposed individuals (Logue et al., 2018), and research examining hippocampal subfields suggested this may be localized to the cornu ammonis (CA) field 4/dentate gyrus (DG), a region implicated in pattern recognition which may underlie fear-related memory generalization (Hayes et al., 2017). It is not clear if these differences in brain morphology differ as a function of the subtype.

Given that dissociation involves alterations in basic perceptual, sensory, emotion, and memory processes, there may be differences in the structure of brain regions underlying these functions that are distinct from PTSD, however, only a few studies have examined differences in brain morphology among those with the dissociative subtype of PTSD versus PTSD alone. To date, there has been one diffusion tensor imaging study of the subtype, which suggested that compared to PTSD alone, the subtype was associated with reduced microstructural integrity in white matter tracts involving the hippocampus, amygdala and thalamus while increased structural integrity was observed in a variety of subcortical white matter tracts (Sierk et al., 2021). Likewise, there has been one whole brain volume study which suggested that the subtype was associated with reduced grey matter temporal gyrus volume but increased volume in precentral and fusiform gyri relative to PTSD (Daniels et al., 2016). No study to date has examined cortical thickness correlates of the subtype and no study has evaluated hippocampal volume associations with the subtype specifically. One small study compared those with PTSD alone to those with PTSD plus DID and reported that those with DID evidenced decreased hippocampal volume bilaterally and in two hippocampal subfields: left CA-4-DG (i.e., the same subfield identified in association with PTSD per Hayes et al., 2017), and left subiculum (Chalavi et al., 2015). However, that study relied on FreeSurfer v5.1 for hippocampal subfield parcellation and the accuracy of that pipeline has been called into question and is no longer recommended (Wisse et al., 2014, 2021).

The structural and functional MRI studies of the dissociative subtype have contributed to important advances in understanding dissociation in the context of PTSD but also raise numerous concerns. The use of categorical determinations to compare dissociative versus PTSD diagnostic groups, while consistent with a subtype structure, limits the sample size for these analyses, particularly given that the subtype is prevalent among a minority of individuals with PTSD. This approach also does not account for the potential confounding effect of PTSD symptom severity, which is important as PTSD severity is often elevated among those with the dissociative subtype (e.g., Wolf et al., 2017) and is associated with differential functional connectivity and brain morphology (e.g., Koch et al., 2016). For these reasons, it remains important to examine associations between dissociation and brain morphology and functional connectivity, to partition the variance associated with PTSD severity, and to utilize large independent samples to comprehensively examine potential brain biomarkers of the subtype.

Neurocognitive Functioning

To the extent that there are structural and/or functional neuroimaging biomarkers of the dissociative subtype of PTSD, we would expect these alterations to also be reflected in neurocognitive performance among individuals with the subtype. A number of studies suggest that dissociation is associated with altered neuropsychological performance (see critical review by Giesbrecht et al., 2008). However, as is the case with neuroimaging studies, it is important to covary for the effects of PTSD and PTSD severity because individuals with PTSD exhibit neurocognitive deficits, including worse visual and verbal memory performance and poorer executive functioning (Vasterling & Hall, 2018; Vasterling et al., 2018). Only one small study has directly compared neurocognitive performance among individuals with PTSD relative to those with PTSD and a dissociative disorder. That study suggested that the dissociative group evidenced worse scores on tests of working and verbal memory than those with PTSD alone, however the dissociative group also showed greater PTSD severity (Roca et al., 2006), making it difficult to disentangle the effects of each symptom set. An experimental study that induced dissociative experiences in healthy undergraduates found that the experimental group evidenced poorer working memory and a greater decline in memory performance across an immediate versus delayed recall task (Brewin et al., 2013). Another study of college students found that those with high levels of dissociation were more likely to make errors of commission when asked to recall an emotionally evocative film clip (Giesbrecht et al., 2007). No studies have comprehensively evaluated how dissociation, covarying for PTSD, is associated with neuropsychological performance across a range of major neurocognitive domains including working memory, executive functions, explicit memory, and tests of self-monitoring.

Genetic Variants

There is reason to suspect that the clinical symptoms of the dissociative subtype and associated alterations in brain morphology and connectivity may be driven by genetic variation. Twin and adoption research suggests a heritability coefficient of approximately 50% for dissociative experiences (Becker-Blease et al., 2004; Jang et al., 1998; Pieper et al., 2011). Only one study to date has evaluated genetic variants specifically associated with dissociative subtype symptoms. In a distinct sample from the one reported on in this study, our group conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of derealization and depersonalization symptom severity among 484 white, non-Hispanic trauma-exposed men and women (Wolf et al., 2014). No significant GWAS (p < 5 × 10−8) results emerged, however 10 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) showed suggestive (p < 10−5) evidence of association with dissociation severity. The peak SNP, rs263232, was located in the gene adenylyl cyclase 8 (ADCY8; p = 6.12 × 10−7), which was previously associated with bipolar disorder (Zandi et al., 2008) and comorbid depression and alcohol-use disorder (Procopio et al., 2013). The gene is implicated in the neurobiology of the stress-response system and in stress-related memory formation and consolidation (e.g., Wieczorek et al., 2010). The SNP remained associated with dissociation severity after covarying for PTSD severity, suggesting that the SNP showed relative specificity for the symptoms that define the dissociative subtype. This study provided the first opportunity to test for replication of the 10 SNPs from Wolf et al. (2014) that showed evidence of association with dissociation severity at the p < 10−5 level of significance.

Aims

The primary aims of this study were to first examine the psychometric evidence for the dissociative subtype of PTSD in a sample of young post-9/11-era military Veterans and to then comprehensively evaluate the biological correlates of the symptoms that define the subtype with respect to patterns of resting state brain connectivity (DMN), neural structure (hippocampal subfield volume and cortical thickness), neurocognitive functioning, and genetic variants, accounting for PTSD symptom severity. We hypothesized that the symptoms that define the dissociative subtype would be associated with reduced DMN activity, differential cortical thickness in frontal regions, differential hippocampal volume, and poorer performance on tests of working and explicit memory and self-monitoring. We also expected to find evidence of replication of previously identified SNPs in association with dissociation severity. We did not advance specific hypotheses concerning the particular hippocampal subregions that would be most associated. In addition, as most psychometric studies have tested only class solutions when evaluating the dissociative subtype of PTSD, this study provided an opportunity to empirically compare the fit of class solutions to dimensional ones (using confirmatory factor analysis; CFA) and hybrid models (using factor mixture models) containing both factors and classes so as to further test the reliability of the dissociative subtype. Failure to empirically compare these competing types of structures can result in erroneous acceptance of a class model when it is not the best fit to the data (Clark et al., 2013).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were from an on-going investigation of Veterans of the post-9/11 conflicts who enrolled in The Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS; McGlinchey et al., 2017) research protocol. To date, the study has enrolled 810 participants across two VA sites in the northeast and southwest United States. Eligibility criteria included Veterans, aged 18–65 who served in the post-9/11 conflicts or were scheduled to deploy to them. Exclusion criteria included inability to complete the protocol due to the acute effects of psychiatric symptoms, active suicidal or homicidal ideation requiring clinical intervention, psychotic or bipolar disorder diagnosis, and neurological or cognitive disorder diagnosis other than that directly related to traumatic brain injury (TBI). The study involved an 8–10-hour session which included a comprehensive neuropsychological battery, self-report surveys, psychodiagnostic interviews, physiological measurements, blood draw, and structural and functional brain MRI. Structured psychiatric diagnostic interviews were completed by PhD-level psychologists and MA-level clinicians, with diagnostic determinations reviewed at regular team meetings adjudicated by multiple psychologists and neuropsychologists. Neuropsychological testing was completed by trained BA-level technicians assessed annually for adherence to standardized test administration. Participants were compensated for their time in the study.

This report is based on a subset of n = 374 Veterans who completed the DSM-5 assessment of PTSD, which includes an assessment of derealization and depersonalization. There were no dissociation data available for Veterans who enrolled in the study earlier (i.e., who completed a DSM-IV assessment). Participant demographics for the n = 374 Veterans who are the focus of this investigation are shown in Table 1. Participants were predominately white, male Veterans with a mean age in their mid-30s. Nearly half met DSM-5 criteria for a diagnosis of current (past 30 days) PTSD. Of these 374 Veterans, n = 208 participated at the northeast site and n = 166 at the southwest site. Neuroimaging data were not available for all subjects, thus the total sample size for neuroimaging analyses ranged from n = 275 (for functional connectivity) to 280 (for volumetric analyses). Primary reasons for missing MRI data were as follows: 46.4% ineligible for MRI (e.g., due to metal in the body or body size), 10.1% withdrew from MRI (e.g., due to claustrophobia), and 13.0% with minor incidental findings or alternate scan parameters that impacted parcellation accuracy. Genetic analyses were conducted in n = 193 white, non-Hispanic participants (see below). Models examining neuropsychological functioning and brain morphology or function excluded Veterans with moderate or severe TBI (n = 21). Of the n = 374 Veterans in this study, a subset of them (n = 163) returned for a follow-up assessment approximately 1.5 years later and were included in a limited number of follow-up analyses examining the stability of the dissociative subtype over time. The majority of missing follow-up data was due to a research shutdown during the COVID-19 pandemic (recruitment for follow-up visits has since resumed); only a small percentage (3.8%) of those with missing follow-up data were lost-to-follow-up.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Descriptive Statistics (n = 374)

| Variable | n (%) | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 339 (90.6) | |

| Age | 36.88 (8.81) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 241 (64.4) | |

| Black | 67 (17.9) | |

| Am. Ind/Alask Native | 9 (2.4) | |

| Asian | 13 (3.5) | |

| Native Hawaii/Pacif Island | 4 (1.1) | |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | 74 (19.8) | |

| Lifetime TBI | 291 (77.8) | |

| Current PTSD dx | 180 (48.1) | |

| Current dissociative subtype | 28 (7.5) | |

| Current PTSD sx sev | 25.55 (16.01) | |

| Current dissociative sx sev | 0.36 (1.05) |

Note. Dissociative subtype prevalence determined via the CAPS-5 interview and scoring rules. PTSD severity possible range: 0 – 80. Dissociation severity possible range: 0 – 8. Am Ind = American Indian; Alask = Alaskan; Pacif = Pacific; TBI = traumatic brain injury; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; dx = diagnosis; sx = symptom; sev = severity.

Measures

Psychopathology.

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., 2013, 2018) was administered to assess the PTSD and dissociative subtype diagnostic criteria and their symptom severity. The CAPS-5 assesses each of the 20 DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, and symptoms of derealization and depersonalization, on a severity scale from 0–4 (Supplementary Materials). The initial prompt for the depersonalization item is as follows: “In the past month, have there been times when you felt as if you were separated from yourself, like you were watching yourself from the outside or observing your thoughts and feelings as if you were another person?” The prompt for the derealization item is: “In the past month, have there been times when things going on around you seemed unreal or very strange and unfamiliar?” Both items have multiple follow-up prompts depending on responses to the initial prompt. Prior versions of these dissociation items (from the DSM-IV version of the CAPS) were used in the original LPA model that identified the subtype (Wolf et al., 2016) and in several other studies (Table S1). Total symptom severity reflects the sum of PTSD (and separately, dissociation) items. A threshold of two or greater on each item is used to determine symptom presence and the DSM algorithm is applied to determine PTSD diagnosis (Weathers et al., 2018). On the CAPS-5, diagnostic criteria for the dissociative subtype are met when the full PTSD criteria are met and either the depersonalization or derealization item is scored at two or greater. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (SCID; First et al., 2015) was administered to assess comorbid psychiatric diagnostic conditions and used in follow-up analyses examining covariates. The SCID is the leading structured diagnostic interview for the assessment of a wide range of psychiatric diagnoses.

Trauma and TBI.

Lifetime trauma exposure was assessed with the self-report Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000), an inventory of 21 different types of traumatic experiences. We examined the total number of different types of traumatic experiences across the lifespan in our follow-up covariate analyses, and separately, the total number of different types of childhood traumatic experiences. Military and non-military-related TBI across the lifetime was assessed with the Boston Assessment of TBI-Lifetime (BAT-L; Fortier et al., 2014), a semi-structured interview. We examined the total number of TBIs across the lifespan as a covariate in follow-up analyses.

Neuropsychological Measures.

Given that a large number of neuropsychological tests were administered in this protocol, we reduced the number of tests by creating latent variables (using CFA) that reflected Working Memory, Executive/Attentional functioning, and Explicit Memory. Factors scores were extracted from these latent variables and used in our main analyses (Table S3). The 21 indicators of these three factors were derived from a variety of neuropsychological tests, including (but not limited to): Digit Span Forward/Backward (Wechsler, 2008); the California Verbal Learning Test-II (Delis et al., 2000); and subtests from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS; Delis et al., 2001). See Supplementary Materials for the full list of tests. We were interested in two additional cognitive phenotypes that were not represented by these factors: tendency to fail to respond to appropriate stimuli (i.e., tests of omission) and tendency to respond incorrectly to stimuli (i.e., tests of commission). These were measured via the CANTAB Affective Go/No Go (www.cantab.com) task which is an index of attentional information processing bias; responses to positive and negatively valanced stimuli on this task were averaged for these analyses. Symptom validity was assessed using the Medical Symptom Validity Test (MSVT; Green, 2003) and was examined in association with dissociative symptoms and included as a covariate in follow-up analyses.

MRI Acquisition and Processing

Neuroimaging data were acquired from the two aforementioned sites with near identical parameters. For the first 27 participants scanned at the site in the northeast, images were acquired on a 3-Tesla Siemens Trio whole-body Tim Trio MRI scanner with the following parameters: two Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MP-RAGE) T1-weighted structural scans with TR=2530ms, TE=3.32ms, flip angle=7°, FOV=256, Matrix=256×256, voxel size=1mm3 and two six minute resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) scans (for which participants were instructed to keep their eyes open and to stay awake) with TR=3000ms, TE=30ms, flip angle=90°, voxel size=3mm3, 38 slices, gradient echo planar imaging (EPI). After a scanner upgrade at this site, the following 155 participants included in this study had two MP-RAGE T1-weighted structural scans and two six-minute rsFMRI scans acquired on a Siemens Prisma scanner with near identical parameters except the MPRAGE TE was 3.35ms. 123 participants were scanned at the southwestern site with a 3-Tesla Siemens Trio MRI scanner with the same parameters as participants scanned with the Prisma at the northeastern site. A scanner flag was included in MRI analyses as a covariate to account for potential scanner and site differences. The two T1-weighted structural scans were averaged to create a single high contrast-to-noise image. A second MP-RAGE was unavailable for 10 individuals. For those individuals, cortical thickness and volume analyses were completed with a single MP-RAGE.

All T1-weighted images were visually inspected for motion artifact and gray-white contrast. Cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation were performed with version 7.1 of the FreeSurfer image analysis suite, which is documented and freely available for download online (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). The technical details of these procedures are summarized in the Supplementary Materials.

Cortical Thickness.

Cortical thickness analyses were performed using FreeSurfer version 7.1. Vertex-wise general linear models were computed over the cortex using FreeSurfer’s mri_glmfit. Images were spatially smoothed at 10mm full-width half-maximum (see data analysis section for details on multiple comparison correction).

Volume Parcellations and Hippocampal Subfield Volumes.

After cortical reconstruction, cortical parcellation volumes as well as hippocampal subfield volumes were acquired with FreeSurfer, version 7.1. The procedure to obtain the volume estimates from cortical parcellations of interest (for follow-up analyses based on initial results) is outlined in Desikan et al. (2006) and summarized in the Supplementary Materials.

An automated pipeline released as part of FreeSurfer version 7.1 was used to perform hippocampal subfield segmentation, which is described in Iglesias et al. (2015). It uses a probabilistic atlas built with ultra-high resolution ex vivo MRI data to produce an automated segmentation of hippocampal substructures. This procedure yields volumetric estimations of each subfield subdivided into head, body, and tail for a total of 19 subfields for each hemisphere. It also outputs whole hippocampus, whole hippocampal head, and whole hippocampal body estimates for each hemisphere. The whole hippocampal head and body encompass the respective subfields that fall within either the head or body: the whole hippocampal head is subdivided into the parasubiculum, presubiculum-head, subiculum-head, cornu ammonis (CA)1-head, CA3-head, Ca4-head, granule cell molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (GC-ML-DG)-head, molecular layer of the hippocampus (molecular layer HP)-head, and hippocampal amygdala transition area (HATA); the whole hippocampal body is subdivided into the presubiculum-body, subiculum-body, CA1-body, CA3-body, Ca4-body, GC-ML-DG-body, molecular layer HP-body, and fimbria; the hippocampal tail and fissure are not encompassed by the hippocampal head or body. Given that we didn’t have lateralized hypotheses for hippocampal subfields, we averaged the subfields across both hemispheres.

Default Mode Network.

DMN resting state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) data were processed using a combination of FreeSurfer (Fischl, Sereno, & Dale, 1999), AFNI (Cox, 1996), and FSL (Jenkinson et al., 2012), based primarily on the FSFAST processing stream (http://freesurfer.net/fswiki/FsFast). Preprocessing of rs-fMRI data involved motion correction, time shifting, concatenation of scans, regression of motion from time series, regression of the global mean as well as white matter and ventricle time courses, and band pass filtering (0.01–0.10 Hz). First, data were sampled and smoothed on the surface and registered to a surface-based template (Fischl et al., 1999). The bilateral superior third of the isthmus of the cingulate, which corresponds to the PCC, was used as the seed region and derived from each participant’s native space surface-based parcellation (Fischl et al., 2002). Connectivity maps were clustered at a vertex-wise threshold of p < 10−20 and yielded four regions in the DMN from each hemisphere: isthmus of the cingulate, angular gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and medial prefrontal cortex.

Genotyping and Associated Statistical Processing

Blood samples were obtained and DNA extracted from buffy coat. Genotyping was derived from the Illumina HumanOmni2.5–8 array. We examined the 10 SNPs from our prior GWAS of derealization/depersonalization symptom severity (Wolf et al., 2014) that achieved p < 10−5 in that study. These SNPs all passed quality control filters and had a minor allele frequencies (MAFs) of at least 5%. Given differences in linkage disequilibrium (LD) as a function of ancestry, these analyses were conducted in the genetically confirmed white, non-Hispanic cohort (n = 193) to match the population structure examined in Wolf et al., 2014. Population substructure within this cohort was modeled through principal components (PC) analysis of 100,000 randomly selected SNPs with at least 5% MAF, and the top three PCs were included as covariates in genotype analyses (see Wolf et al., 2019 for details).

Data Analyses

We first conducted LPAs to determine if a dissociative subtype of PTSD would emerge (defined by high PTSD symptom severity and uniquely high ratings on symptoms of derealization and/or depersonalization on the CAPS-5). We tested solutions with 2 – 5 classes using Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2020). Models were estimated with the robust maximum likelihood estimator with an increased number of initial stage random starts and final stage optimizations. Models with different class solutions were compared against each other using the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT; p-values < .05 suggest the class solution is preferred over a model with one less class; McLachlan & Peel, 2000), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMRA; the associated p-value is interpreted in the same manner as the BLRT p-value; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001), and the Bayesian (Schwartz, 1978) and Akaike information criteria (BIC and AIC, respectively; models with smaller values are preferred). We also examined entropy (an index of class distinction with higher values preferred) and considered the size and interpretability of the class compositions when determining the optimal class solution. The selection of the optimal class solution was guided by examination of these parameters as a whole. We also compared the fit of the best class solution to CFA and factor mixture model solutions using BIC (Supplementary Materials).

After determining the optimal solution, we compared those assigned to the dissociative subtype of PTSD to those assigned to the other classes from the LPA on each CAPS-5 item severity score, trauma exposure, number of lifetime TBIs, comorbid SCID-based psychiatric diagnoses, self-reported non-specific neurological symptoms, and demographic characteristics (including service-related disability) using ANOVA or Chi-square tests as appropriate. We also compared assignment to the dissociative class per the LPA with assignment to the dissociative subtype of PTSD diagnosis per the CAPS-5 scoring rules using chi-square analyses. We did this both for the cross-sectional associations and for testing if assignment to the dissociative subtype at baseline was associated with dissociative subtype diagnosis at follow-up (for the n = 163 subset who returned for a second assessment), per the CAPS-5.

Next, we conducted a series of regressions to compare neurobiological correlates of dissociative symptom relative to PTSD symptom severity. Given that individuals assigned to the dissociative subtype class per the LPA also showed greater total PTSD symptom severity and given the relatively low prevalence of the dissociative subtype, we examined the neurobiological correlates of the symptoms that define the subtype by including total dissociation and PTSD symptom severity as cross-sectional predictors in the models (see Supplementary Materials). This was conducted for five families of tests: (1) DMN functional connectivity parameters; (2) hippocampal subfield volume; (3) whole brain cortical thickness; (4) neuropsychological functioning; and (5) candidate SNPs. Each regression model included the covariates PTSD symptom severity, age, and sex in the first step of the model. Models evaluating neuroimaging outcomes additionally covaried for scanner and, as appropriate, for intracranial volume (i.e., eTIV, included in volumetric analyses only) in this first step of the model. Dissociation (derealization plus depersonalization) symptom severity scores on the CAPS-5 were added in the second step. The analyses examining hippocampal subfield volume were organized into three sets of regression models. In the first, we examined the whole hippocampal volume. In the second, we examined the hippocampal head and body superordinate parcellations. In the third set of analyses, we examined the subordinate parcellations from the head or body based on which superordinate region was significant in the prior set of analyses. In each, we covaried for age, sex, PTSD severity, scanner, and eTIV. The 95% confidence interval (CI) is provided for dissociation associations that were at least nominally (p < .05) significant.

We also conducted follow-up analyses to evaluate potential confounds in step one of the models, including lifetime number of TBIs, lifetime trauma exposure, childhood trauma exposure, and antidepressant use (in separate models). For the neuropsychological measures, we additionally covaried for a test-of-effort in follow-up analyses (MSVT), after first demonstrating that effort was not associated with dissociative symptom severity. For the DMN analyses, we additionally covaried for movement in the scanner.

For analyses focused on neuropsychological functioning and neuroimaging parameters (except the whole-brain cortical thickness model), we computed multiple testing corrected p-values using a Monte Carlo null simulation permutation procedure with 10,000 replicates. This procedure accounts for the number of dependent variables in each family of tests and their correlational structure (Miller et al., 2015). This approach is preferable to both a Bonferroni correction and the false discovery rate correction, which are conservative when the variables being analyzed are correlated. For example, as there are four bilateral DMN parameters, the dissociative symptom severity scores were shuffled across participants 10,000 times, and these replicates were each analyzed versus the eight dependent variables (four bilateral regions). The minimum p-value across these eight analyses was recorded to generate a null distribution for the smallest p-value expected for the number of tests and correlation structure between the tests. The percentile of the observed p-values in the null distribution is reported as the simulation-based adjusted p-value (padj). For the whole brain cortical thickness analyses, multiple testing correction was achieved using FreeSurfer version 7.1 with the mri glmfit-sim tool using the cache option, which uses a precomputed Z Monte Carlo simulation procedure (Hagler et al., 2006). We used a vertex-wise/cluster forming threshold of p < .0001 and a cluster wise p-value of p < .05.

Genotype analyses were conducted using linear regression models for each of the 10 SNPs as predictors of dissociation severity. The first step of the model included age, sex, the top 3 ancestry PCs, and PTSD severity; the second step included a given candidate SNP. As these analyses tested for evidence of replication (Wolf et al., 2014), we did not conduct a multiple testing correction across the ten SNPs. Rather, p < .05 was sufficient for evidence of replication.

Transparency and Openness Promotion

To gain access to these data, qualified investigators may apply to the TRACTS Data Repository by writing to Dr. Regina McGlinchey. Analyses were conducted using Mplus, R, SPSS and FreeSurfer’s mri_glmfit. Analytic code and associated statistical output from these analyses are available by writing to Dr. Erika Wolf. This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Results

Prevalence of the Dissociative Subtype per the CAPS-5

The prevalence of current DSM-5 PTSD per the CAPS-5 was 48.1% (n = 180) and of those with current PTSD, 15.6% (n = 28) met criteria for the dissociative subtype of PTSD on the CAPS-5 (Table 1). Of the full sample, 7.5% were diagnosed with the dissociative subtype of PTSD on the CAPS-5.

Latent Profile Analysis

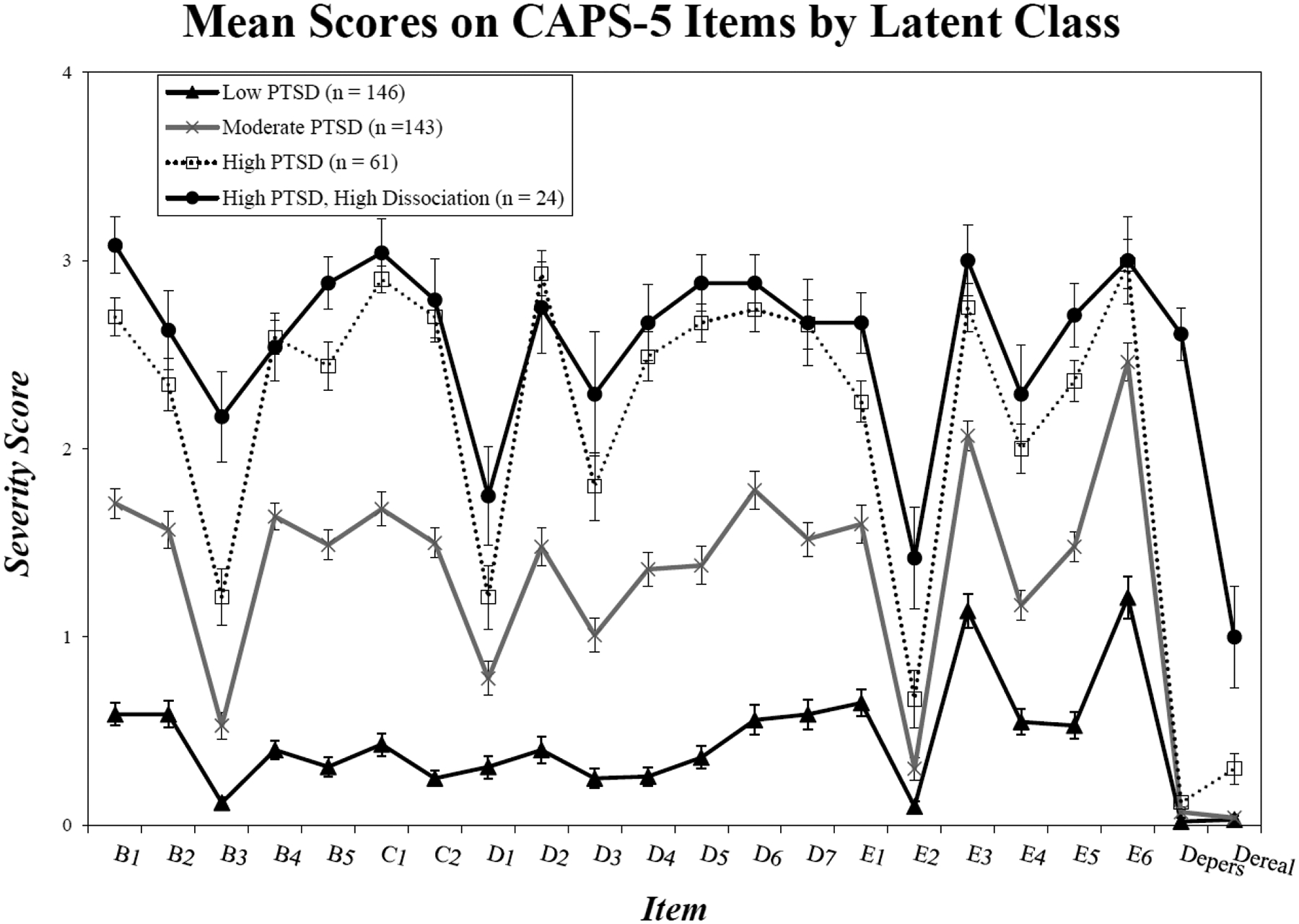

The LPA of the 20 DSM-5 PTSD symptom severity scores and the two dissociation items suggested that the best fitting class model was the 4-class one (Table 2). Each successive addition of a class from the 2 to 5 class models was associated with significant BLRT p-values (suggesting that each class model was preferred over the model with one fewer classes) and the AIC and BIC values decreased with the addition of each class, with minimal impact on the entropy classification statistic. However, the 5-class model was problematic in that the best loglikelihood value was not replicated, despite the use of random starts, and the smallest class comprised just 3.7% of the sample. Together, this suggests that the model extracted too many classes for the data and that the 4-class model was superior. Evaluation of the 4-class solution (Figure 1) revealed a class defined by low symptom severity on all items (38.9% of the sample), a class with moderate PTSD symptoms and no symptoms of dissociation (37.6%), a class with high PTSD symptoms and no or minimal dissociative symptoms (17.1%) and a class with high severity of both PTSD and dissociative symptoms (6.5%), which we refer to as the dissociative subtype. We also empirically compared the best LPA solution to dimensional (CFA) and hybrid dimensional/class (factor mixture model) solutions and found that the 4-class LPA model was superior (Supplementary Materials and Table S4).

Table 2.

Fit of Competing Latent Profile Analysis Solutions (n = 374)

| Model | BLRT p | LMRA p | BIC | AIC | Entropy | Smallest class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 class | < .0001 | < .0001 | 23094.180 | 22831.255 | .95 | 45.5% |

| 3 class | < .0001 | .02 | 22473.824 | 22120.641 | .93 | 19.8% |

| 4 class | < .0001 | .18 | 22133.020 | 21689.579 | .94 | 6.5% |

| 5 class | < .0001 | .45 | 21893.452 | 21359.753 | .95 | 3.7% |

Note. The best fitting solution is shown in bold font. In the model with 5 classes, the best loglikelihood value was not replicated and the standard errors were not trustworthy. BLRT = bootstrapped likelihood ratio test; LMRA = Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; AIC = Akaike information criterion.

Figure 1.

The figure shows mean scores (and SEs) for each PTSD and dissociation item as a function of class membership derived from the best-fitting 4-class LPA solution. The dissociative class evidenced greater severity scores than the high PTSD class on items B3 (flashbacks, p < .001), E2 (recklessness, p < .001), depersonalization (p < .001), and derealization (p < .001).

We examined how the LPA classes differed from each other on baseline mean scores on each CAPS-5 item submitted to the analysis (Figure 1) and on total current PTSD symptom severity. The ANOVA revealed significant omnibus F-tests for all items (ps < .001; Table S5), but the follow-up pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s HSD revealed only a limited number of significant differences between the high PTSD versus the dissociative classes (i.e., the primary comparison of interest). The dissociative class evidenced greater severity than the high PTSD class on items B3 (flashbacks, p < .001), E2 (recklessness, p < .001), depersonalization (p < .001), and derealization (p < .001). They were also higher on total current PTSD severity, Mdiss = 52.08, SD = 9.53 versus Mhigh = 46.33, SD = 5.57 (p = .001). There were no pairwise differences between the dissociative and high PTSD classes on childhood trauma (p = 1.0), adult trauma (p = .94), or the total number of lifetime TBIs (p = .19). A Chi-square analysis comparing just the dissociative subtype classification against the high PTSD one revealed no differences in the prevalence of comorbid current mood disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol-use disorders, non-alcohol substance-use disorders, or eating disorders (smallest p = .23). Similarly, there were no differences between the LPA-defined dissociative subtype versus the high PTSD class on self-reported neurological symptoms, including self-reported history of vertigo, fainting, headaches, and tremors (smallest p =.09). With respect to demographic characteristics, there were no significant differences between the groups on sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, or VA Service Connection (i.e., disability) application (smallest p = .08).

There was good overlap between the empirical 4-class LPA-based dissociative class determinations and those diagnosed with the dissociative subtype on the CAPS-5, χ2 (6, n = 363) = 484.27, p < .001. Specifically, of those assigned to the dissociative subtype class per the LPA, all but one (95.7%) were also diagnosed with the dissociative subtype of PTSD on the CAPS-5. Similarly, of those identified with the dissociative subtype of PTSD per the CAPS-5, 78.6% were assigned to the dissociative subtype on the LPA while 17.9% were assigned to the high PTSD class and 3.6% to the moderate PTSD class per the LPA.

In the subset of n = 163 participants who returned for a follow-up assessment (on average, 553 days later, SD = 194), we found that assignment into the dissociative subtype per the LPA at baseline was associated with subsequent dissociative subtype diagnosis per the CAPS: χ2 (6, n = 163) = 113.86, p < .001. Specifically, of those assigned to the dissociative subtype at baseline, 83.3% were identified as meeting the diagnostic criteria for the dissociative subtype of PTSD on the CAPS-5 at follow-up (and the remainder met criteria for PTSD without the subtype at follow-up). Comparatively, of those assigned to the high PTSD (no dissociation) class at baseline, just 20.0% met the criteria for the dissociative subtype at follow-up, 46.7% met criteria for PTSD without the subtype at follow-up, and 33.3% did not meet criteria for PTSD at follow-up.

Associations with Default Mode Network

We next examined the eight DMN functional connectivity parameters (four per hemisphere). There was a nominally significant negative association (Table 3) between dissociation severity and functional connectivity between the bilateral PCC and right isthmus of the cingulate (B = −.013, CI = −.024 to −.003, p = .015; Figure 2), although it was not significant after correction for multiple testing (padj = .097). Follow-up testing revealed that this nominally significant association was not better accounted for by the number of lifetime TBIs, lifetime or childhood trauma exposure, antidepressant use, or motion in the scanner, as these potential confounders were not associated with connectivity between these regions and dissociation severity remained nominally associated with connectivity in this region when any of these variables were included in the model (p < .020). Based on these results, we performed exploratory analyses examining the association between dissociation severity and bilateral (averaged across right and left hemisphere) posterior cingulate gyrus (PCG) volume and right isthmus (i.e., to be consistent with the nominal DMN association with bilateral PCC seed and right isthmus). Dissociation severity was positively associated with bilateral PCG volume (B = 46.43, CI = 2.39 to 90.47, β = .112, p = .039) but not with right isthmus volume (B = 31.23, β = .086, p = .133), covarying for age, sex, scanner, eTIV, and PTSD severity.

Table 3.

Dissociation as a Predictor of Default Mode Network Functional Connectivity Parameters (n = 275)

| PTSD Severity | Dissociation Severity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | β | p | p adj | B | β | p | p adj |

| Left hemisphere | ||||||||

| PCC-frontal | −.001 | −.121 | .046 | NA | .005 | .053 | .432 | .969 |

| PCC-temporal | −.001 | −.162 | .007 | NA | .0003 | .003 | .968 | 1.0 |

| PCC-isthmus | 6.120E−.05 | −.013 | .839 | NA | −.007 | −.089 | .190 | .705 |

| PCC-angular gyrus | −.001 | −.088 | .147 | NA | −.007 | −.071 | .290 | .864 |

| Right hemisphere | ||||||||

| PCC-frontal | −.001 | −.130 | .032 | NA | .009 | .077 | .251 | .817 |

| PCC-temporal | −.001 | −.126 | .037 | NA | .008 | .064 | .335 | .909 |

| PCC-isthmus | −.0001 | −.044 | .479 | NA | −.013 | −.165 | .015 | .097 |

| PCC-angular gyrus | .0003 | .016 | .796 | NA | −.013 | −.105 | .117 | .525 |

Note. Models also adjusted for age, sex, and scanner in the first step. The multiple testing correction was adjusted over all 8 phenotypes examined. PCC = posterior cingulate cortex. NA = not applicable; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; adj = adjusted.

Figure 2.

The figure shows brain regions that were implicated in the default mode network (DMN) connectivity analyses. The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; defined as the posterior portion of the superior third of the bilateral isthmus of the cingulate) was the seed region and is shown in light blue and the right isthmus is shown in dark blue. Functional connectivity between the seed and right isthmus cingulate was nominally associated with dissociation severity after correcting across the eight (four per hemisphere) DMN variables.

Associations with Hippocampal Subfield Volume

As shown in Table 4, there was a significant overall positive relationship between dissociation severity and whole hippocampal volume (B = 36.94, CI = 2.86 to 71.02, p = .034).3 Follow-up analyses demonstrated that this effect remained significant (largest p = .044) when additionally covarying for lifetime TBIs, lifetime trauma exposure, childhood trauma exposure, and antidepressant use, none of which were associated with whole hippocampal volume. In the second set of analyses evaluating the hippocampal head and body separately, there was a corrected significant positive relationship with the whole hippocampal head (B = 24.30, CI = 4.29 to 44.30, p = .017, padj = .032) but not the whole hippocampal body (p = .117, padj = .192). The former association also remained significant (largest p = .023) when further adjusting for lifetime TBIs, lifetime trauma exposure, childhood trauma, and antidepressant use, which were not associated with volume. Based on this, we further examined the nine hippocampal subfield parcellations that are subsumed by the whole hippocampal head. This third set of analyses revealed several nominally significant associations with: the molecular layer hippocampal head (B = 5.38, CI = 1.31 to 9.44, p = .010, padj = .053), CA1 head (B = 8.42, CI = 1.39 to 15.44, p = .019, padj = .092), GC-ML DG head (B = 2.50, CI = .43 t 4.56, p = .018, padj = .088), and CA4 head (B = 2.03, CI = .41 to 3.66, p = .015, padj = .074), which are shown in Figure 3. The most significant association (with the molecular layer hippocampal head) was further examined and withstood additional correction for lifetime TBIs, lifetime and childhood trauma exposure, and antidepressant use (largest p = .012).

Table 4.

Dissociation as a Predictor of Hippocampal Subfield Volume (n = 280)

| PTSD Severity | Dissociation Severity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | β | p | p adj | B | β | p | p adj |

| 1. Whole hip | .143 | .007 | .891 | NA | 36.939 | .116 | .034 | NA |

| 2. Hip head & body | ||||||||

| a. Hip head | .459 | .037 | .452 | NA | 24.296 | .130 | .017 | .032 |

| b. Hip body | −.114 | −.017 | .745 | NA | 9.264 | .090 | .117 | .192 |

| 3. Hip head subfields | ||||||||

| a. Subiculum head | .020 | .012 | .838 | NA | 2.163 | .083 | .187 | .600 |

| b. Presubiculum head | −.012 | −.011 | .834 | NA | 1.592 | .101 | .088 | .345 |

| c. CA1 head | .172 | .041 | .422 | NA | 8.416 | .133 | .019 | .092 |

| d. Parasubiculum | −.034 | −.050 | .369 | NA | −.005 | 0 | .994 | 1.0 |

| e. ML head | .086 | .035 | .488 | NA | 5.378 | .145 | .010 | .053 |

| f. GC-ML DG head | .080 | .064 | .205 | NA | 2.497 | .132 | .018 | .088 |

| g. CA4 head | .044 | .045 | .373 | NA | 2.034 | .136 | .015 | .074 |

| h. CA3 head | .065 | .055 | .296 | NA | 1.584 | .089 | .128 | .454 |

| i. HATA | .037 | .061 | .229 | NA | .638 | .069 | .217 | .657 |

Note. Subfield volumes were averaged across hemispheres. Models adjusted for age, sex, scanner, and total head volume. The p-value adjustment was performed for each set of analyses (as enumerated in the table) and we only proceeded to test successive subfield regions if the overarching region evidenced a corrected significant association with dissociation severity in the second step of the model. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; Hip = hippocampus; CA = cornu ammonis; ML = molecular layer; GC = granule cell, DG = dentate gyrus; HATA = hippocampal-amygdaloid transition region; NA = not applicable; adj = adjusted.

Figure 3.

Sample subject segmentation of significant hippocampal subfields. Subfields shown are the four regions that were at least nominally significant in regression analyses. CA = cornu ammonis; GC-ML-DG = granule cell molecular layer of the dentate gyrus; HP = hippocampus; L = left; R = right.

Associations with Whole-Brain Cortical Thickness

We examined whole brain cortical thickness associations with dissociation severity covarying for age, sex, scanner, and PTSD severity. Across the hemispheres, there were no significant whole brain associations that survived multiple comparison correction.

Associations with Neurocognitive Functioning

We initially examined if dissociation severity was associated with increased odds of “failing” the MSVT. A total of 32 participants were above the collective standard cut-points on the MSVT and a logistic regression revealed that dissociation severity was not associated with MSVT failure (OR = 1.06, CI = 0.79 to 1.42, p = .69), but PTSD severity was (OR = 1.04, CI = 1.01 to 1.06, p = .01). We next examined the neurocognitive constructs of interest (Table 5). Covarying for age, sex, and PTSD severity, dissociation severity was not associated with the Working Memory factor scores (p = .079), and was only nominally associated with Executive/Attentional factor scores (B = .26, CI = .008 to .51, p = .043, padj = .153) and Explicit Memory factor scores (B = −.06, CI = −.12 to −.002, p = .041, padj = .149). Dissociation was not associated with Affective Go/No Go mean commission errors (p = .458) and was nominally associated with Affective Go/No Go mean omission errors (B = 1.34, CI = .23 to 2.45, p = .018, padj = .079). We conducted secondary analyses of the Affective Go/No Go mean omission errors by additionally covarying for MSVT failure and total number of lifetime TBIs. Dissociation severity remained nominally and positively associated with omission errors (p = .029) with these additional variables included in the model.

Table 5.

Dissociation Severity as a Predictor of Neurocognitive Functioning (n= 337)

| PTSD Severity | Dissociation Severity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | β | p | p adj | B | β | p | p adj |

| Working Memory FS | −.013 | −.204 | .005 | NA | −.095 | −.101 | .079 | .248 |

| Exec/Attn FS | .031 | .213 | .005 | NA | .260 | .117 | .043 | .153 |

| Explicit Memory FS | −.007 | −.220 | .003 | NA | −.061 | −.116 | .041 | .149 |

| Commission Errors | .064 | .204 | .019 | NA | −.433 | −.070 | .458 | .882 |

| Omission Errors | .109 | .339 | .004 | NA | 1.338 | .210 | .018 | .079 |

Note. Models adjusted for age and sex. The first three dependent variables listed were factor scores derived from a confirmatory factor analysis of raw scores on select neuropsychological measures (Supplementary Materials for details). Higher scores on the Working Memory and Explicit Memory factors indicate better performance whereas higher scores on the Exec/Attn factor and on Commission and Omission Errors indicate worse performance. Adj = adjusted; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; FS = factor score; Exec/Attn = Executive/Attentional; NA = not applicable.

Associations with Candidate SNPs

Table 6 shows the association between each of the 10 candidate SNPs and dissociation severity, covarying for age, sex, the top three ancestry PCs, and PTSD severity. The SNP rs263232 in the gene ADCY8 evidenced a significant association with dissociation severity (B = .43, CI = .05 to .82, p = .026). In particular, each additional copy of the minor allele (A) was associated with a .434 score increase in dissociation severity. The direction of effect was the same as we previously reported (Wolf et al., 2014). No other candidate SNPs were significantly associated with dissociation.

Table 6.

Candidate Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Associations with Dissociation Severity (n = 193)

| SNP | Gene | CHR | BP | MAF | Ref Allele | B | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs9725031 | SIPA1L2 | 1 | 232444455 | 0.118557 | A | −.168 | .166 | .313 |

| rs1915919 | KAT2B | 3 | 20083881 | 0.408247 | A | −.045 | .115 | .693 |

| rs77006546 | near CMAHP | 6 | 25219582 | 0.04433 | G | .265 | .280 | .343 |

| rs71534169 | DPP6 | 7 | 154592866 | 0.081443 | C | .098 | .175 | .576 |

| rs62488971 | TRMT9B | 8 | 12808108 | 0.054865 | A | .052 | .204 | .800 |

| rs2460905 | TRMT9B | 8 | 12834600 | 0.085567 | A | .118 | .181 | .514 |

| rs2466273 | TRMT9B | 8 | 12866004 | 0.087992 | C | .126 | .181 | .488 |

| rs263232 | ADCY8 | 8 | 131808169 | 0.078351 | A | .434 | .193 | .026 |

| rs682457 | near MIR3166 | 11 | 87949532 | 0.186722 | G | −.067 | .145 | .645 |

| rs77963519 | near MEX3B | 15 | 82193846 | 0.073347 | A | −.129 | .194 | .506 |

Note. Models covaried for age, sex, the top three ancestry principal components, and PTSD symptom severity. The significantly associated variant is shown in bold font. BP location is referenced to the Human Genome (HG) 119 build. MAF are based on the largest white non-Hispanic cohort genotyped cohort (regardless of DSM-IV/DSM-5 PTSD assessment) of n = 485. SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism; CHR = chromosome; BP = base pair; MAF = minor allele frequency; Ref = reference; SIPA1L2 = signal induced proliferation associated 1 like 2; KAT2B = lysine acetyltransferase 2B; CMAHP = cytidine monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase, pseudogene; DPP6 = dipeptidyl peptidase like 6; TRMT9B = probable tRNA methyltransferase 9B; ADCY8 = adenylate cyclase 8; MIR3166 = microRNA 3166; MEX3B = Mex-3 RNA binding family member B.

Discussion

The literature concerning the dissociative subtype of PTSD has consistently identified a unique subgroup of individuals with PTSD and marked symptoms of derealization and depersonalization. However, evaluating the validity of the subtype requires more than just a reliable psychometric structure. It is critical to test if the subtype features are associated with differential risk factors, neurobiology, clinical correlates, symptom course, and/or treatment response. Though research has begun to address this question (e.g., Nicholson et al., 2019; Harricharan et al., 2020), results with respect to the neurobiological correlates of the subtype have been inconsistent. This may be due to sample size constraints associated with the small number of individuals with the subtype when categorical scoring rules are applied, failure to account for PTSD symptom severity, which may be elevated among those with the dissociative subtype, or variability in neural seed regions and other imaging parameters that impact the results of functional connectivity analyses. To our knowledge, this was the first study to broadly evaluate the biological correlates of the symptoms that define the dissociative subtype of PTSD, with respect to neurocognitive performance, brain structure and function, and genetics, using a large cohort with a high prevalence of PTSD. We evaluated these correlates in a manner that incorporated data from all participants and covaried for the possible confounding effects of PTSD symptom severity.

Our results suggested that, per the LPAs, the prevalence of the dissociative subtype of PTSD was 7.5% among the full sample of trauma-exposed Veterans, which represented 15.6% of the subset with current PTSD. While numerous studies have reported similar subtype prevalence estimates of 15% or less (e.g., Wolf, Miller et al., 2012; Blevins et al., 2012; Stein et al., 2013), some have suggested dramatically higher estimates (e.g., > 30 or 40%; Frewen et al., 2015; Hansen et al., 2016). These differences may be due to variation in assessment procedures (such as web-based and self-report assessments as in Frewen et al., 2015) and sample characteristics (such as inclusion based on childhood sexual abuse history as in Hansen et al., 2016) that may yield higher prevalence estimates. In this study, identification of individuals with the dissociative subtype of PTSD per the LPA was nearly identical to that using standard CAPS-5 scoring rules (i.e., meeting full criteria for PTSD plus a score of two or greater on either derealization or depersonalization), which provides support for the accuracy of this scoring algorithm. Results demonstrated that the class structure was the best fit to the data when compared against dimensional and hybrid models, providing further evidence that elevated scores on derealization and/or depersonalization reflect a unique type of PTSD comorbidity. The dissociative subtype appeared to be highly stable over time, with over 80% of those identified on the baseline LPA still meeting CAPS-5-based diagnostic criteria for the subtype approximately 1.5 years later, suggesting the importance of identifying these individuals as soon as possible through standard assessment of dissociation in trauma-exposed individuals in clinical, research, and forensic settings. This carries implications for our ability to accurately identify risk factors, correlates, and treatments for PTSD if this variability in the diagnosis is not adequately measured.

With respect to structural neuroimaging parameters, we found that dissociation symptom severity was associated with increased bilateral hippocampal volume, an effect that appeared to be driven by the hippocampal head, and more specifically, by the molecular layer head (with nominally significant positive associations also observed for CA1, GC-ML DG head, and CA4 head). These associations were not better accounted for by PTSD symptom severity. In a prior study, whole hippocampal volume was reduced among individuals with DID versus healthy individuals, though PTSD was not considered in those analyses (Vermetten et al., 2006). A study of hippocampal subfield volume among those with DID, which did not partial out the effects of PTSD, also reported that dissociative amnesia (but not depersonalization or derealization symptoms) was associated with decreased hippocampal volume and decreased bilateral CA1 subfield volume in particular (Dimitrova et al., 2021). Similarly, PTSD has been associated with smaller bilateral CA1 (Postel et al., 2021), CA2–3 dentate gyrus (DG; Postel et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2010), and bilateral CA4/DG volume (Hayes et al., 2017), although some effects for CA1 have been lateralized (Chen et al., 2018).

Thus, the finding for increased subfield volume in this study was surprising. However, it is not without precedent. In particular, administration of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine, which shows success in treating refractory depression (Serafini et al., 2014) and PTSD (Feder et al., 2021), is associated with acute, though transient, dissociative symptoms (Mello et al., 2021; Short et al., 2018) and with immediate increases in hippocampal volume (Höflich et al., 2021) and cerebral blood flow (Bryant et al., 2019) among healthy adults. The time course of the dissociative side effects and increased hippocampal volume overlaps, though to our knowledge no study has examined the correlation between these responses to ketamine. Animal studies provide further support for ketamine’s impact on unusual perceptual (schizophrenia-like) symptoms (Keilhoff et al., 2004) and immediate changes in brain structure following ketamine administration, including rapid increases in the CA1 and granular cell layer of the DG in rats (Ardalan et al., 2017). Increased hippocampal volume is thought to reflect neurogenesis as suggested by animal experiments demonstrating that ketamine administration elicits increased neurogenesis in the DG (Keilhoff et al., 2004), and increased hippocampal dendritic spine density (Treccani et al., 2019). The DG, which evidenced nominally increased volume in association with derealization/depersonalization symptoms in this study, is a particularly interesting hippocampal subfield to consider in association with dissociation. Though best known for its role in pattern separation, the DG also receives all manner of sensory input and is critical for object-space and spatial learning (Kesner, 2018). These processes may be altered among those with impaired proprioception (as in depersonalization) or with a disintegrated sense of the physical world (as in derealization). Thus, one possibility is that the neurobiology of ketamine-induced dissociative symptoms is similar to the pathophysiology of endogenous dissociative experiences: increased hippocampal volume could reflect increased neurogenesis and associated information overload, disintegration of incoming sensory information, and altered perception and learning. Additional research is necessary to test the role of NMDA receptors in dissociative experiences.

With respect to neural function, we found that derealization/depersonalization symptoms were nominally associated with decreased functional connectivity between the bilateral PCC and right isthmus. Dissociation symptoms were also associated with increased brain volume in bilateral PCG, an area with projections from the parahippocampus and hippocampal formation (Buckner et al., 2008). The PCC is critical for integration of information, consciousness, and related processes such as mind wandering, day dreaming, and retrieval of autobiographical memory (Buckner et al., 2008; Leech & Sharp, 2014). It also appears to be specifically related to both interoceptive and exteroceptive perception, including sense of self-location and direction (Guterstam et al., 2015), and altered states of bodily awareness, such as body illusions (Park et al., 2016). A case study found that a tumor in the PCC was associated with symptoms consistent with depersonalization (Hiromitsu et al., 2020) and similarly, stimulation of the region has been associated with the perception of limb movement when at rest (Popa et al., 2019). The isthmus is adjacent and posterior to the PCC; it connects the PCC to the parahippocampal gyrus. This tract has previously been shown to be associated with the flattened affect commonly observed in schizophrenia (Whitford et al., 2014); the volume of the isthmus is associated with symptoms of depression (McLaren et al., 2016), and a case study suggested that damage to this region elicited symptoms of spatial disorientation and confusion (Katayama et al., 1999). Given this, decreased functional connectivity between the PCC and isthmus could reflect inefficient or slowed synchronization between these regions of the brain that are critical for sensory integration, consciousness, and the physical sense of self and place. Our finding of decreased DMN connectivity is consistent with at least one EEG study of pre-treatment dissociative conditions, with data suggesting increased DMN connectivity following treatment (Schlumpf et al., 2021). It is important to note that we studied trait but not state dissociation, thus this functional connectivity correlate could represent a vulnerability to derealization/depersonalization rather than (or in addition to) the neurobiology of an active dissociative state.

These alterations in brain structure and function could potentially underlie the nominally significant associations we observed between dissociation and executive functioning, explicit memory, and self-monitoring, as indicated by errors of omission (the latter association just missed the adjusted p-value cut-off). An association between dissociative symptoms, including depersonalization/derealization specifically, and greater errors of omission has previously been reported among traumatized refugees (Lee et al., 2016); we did not replicate prior results suggesting associations between dissociation and commission errors (Giesbrecht et al., 2007). Unlike the results obtained for the neural imaging parameters, these neurocognitive deficits were not specific to the dissociative symptoms as PTSD symptoms were also associated with each of these neurocognitive variables (and additionally with worse working memory performance and more commission errors). Thus, neuropsychological characteristics may not sufficiently distinguish PTSD from its dissociative subtype, though neurocognitive functioning may still be an important clinical consideration for treatment of the subtype.

We replicated the association between the SNP rs263232 in the gene ADCY8 and derealization/depersonalization symptoms; this SNP previously emerged as the peak SNP from the only published GWAS of derealization/depersonalization symptoms (Wolf et al., 2014). Adenylyl cyclase 8 (AC8) is a calcium-dependent enzyme that is involved in the conversion of ATP to cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate (cAMP). AC8 deficient mice evidence normal behavioral indicators of anxiety at baseline but show reduced anxiety-like responses following restraint stress (Razzoli et al., 2010; Schaefer et al., 2000). Preclinical evidence also suggests that AC8 is associated with slowed hippocampal-mediated fear-related learning and worse spatial learning and memory (Zhang et al., 2008). Similarly, a recent study of peregrine falcons found that the ADCY8 gene was indicated in long-term memory for migratory patterns (Gu et al., 2021), further highlighting its role in spatial learning and memory. Mice lacking both the ADCY8 and ADCY1 gene show deficits in long term potentiation in the CA1 hippocampal subfield (Wong et al., 1999), an effect which can be reversed by AC8 administration in the mouse forebrain (Wieczorek et al.,2012). Collectively, these studies suggest that ADCY8 is important for fear-related spatial learning and memory, particularly in the hippocampus, and that alterations in the gene relate to failures to respond to environmental stressors in a contextually congruent manner (Wieczorek et al., 2012). These types of deficits could relate to dissociated states defined by lack of response to the environment and spatial disorientation, consistent with depersonalization and derealization.

Limitations & Future Directions

Results should be considered in light of a number of limitations. This study was comprised of primarily male military Veterans and thus the generalizability is limited to this group. Genetic association results were further limited to the white, non-Hispanic Veterans, which was the largest ancestrally homogenous subgroup in the study. The sample size was small for genetic association studies, however, to our knowledge, this study was the first to test for replication of SNP effects identified in a prior GWAS. We did not have a replication sample to test the reliability of the results. Concerns have recently been raised about the use of FreeSurfer’s hippocampal subfield parcellations (Wisse et al., 2021). Specifically, we used FreeSurfer’s (version 7.1) automated procedures to segment the hippocampus on 1mm3 T1-weighted images, a resolution at which hippocampal subfield structures can rarely be visualized (Wisse et al., 2021). Hippocampal subfield segmentations on 1mm3 T1-weighted images have not been validated against manual segmentations on 1mm3 T1-weighted images (Wisse et al., 2021). However, this concern is offset by the results of a recent study demonstrating high test-retest reliability of FreeSurfer’s automated segmentation procedure (Brown et al., 2020). Future work should attempt to replicate these findings with higher resolution T1-weighted images and manual segmentations. A number of our results were nominally significant (p < .05) but just failed to meet the multiple testing adjusted p-value threshold, which could indicate insufficient sample size for observing statistical significance or may suggest the nominally significant associations were due to Type I error. This highlights the importance of efforts to replicate these results in larger cohorts. While we examined numerous potential confounds to our results, including trauma exposure, TBI, intracranial volume, effort on neuropsychological tests, medication use, and motion in the scanner, there are undoubtedly other factors that could potentially confound our results. We did not actively elicit dissociative states and thus the neurobiology of state dissociation may differ from these results. Future research should incorporate measures of both state (e.g., with The Clinician Administered Dissociative States Scale; Bremner et al., 1998) and trait (e.g., with The Dissociative Subtype of PTSD Interview; Eidhof et al., 2018) dissociation to delineate biological features associated with each process. Further, as analyses were based on cross-sectional methods, we cannot determine causality or identify if the neurocognitive correlates represent a vulnerability factor for dissociation or a consequence of it.

In addition to the importance of future replication efforts, follow-up research concerning the biological correlates of the subtype could evaluate if these biomarkers can be used to inform treatment. For example, work evaluating ADCY8-related biological pathways could lead to novel pharmacotherapeutics to treat dissociative symptoms. Likewise, future psychotherapy research could test if brain morphology and function are differentially altered following PTSD treatment for those with versus without the subtype. Future research will need to carefully consider the appropriate composition of cohorts, as it would be most informative if dissociative subtype groups are compared against PTSD groups that are matched for PTSD symptom severity, psychiatric comorbidity, trauma histories, and demographic characteristics. An ongoing challenge to this line of work will be achieving sufficient sample sizes to adequately power such studies, given that the subtype comprises a minority of the PTSD population. Consortium efforts could help address this issue if standardized definitions of the subtype are coordinated across investigators.

Conclusions