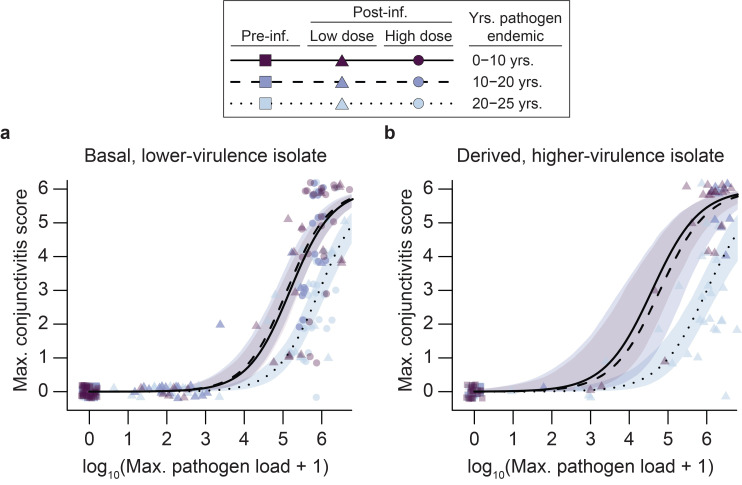

Fig 2.

House finch populations (n = 2–3 populations per endemism category) in which the bacterial pathogen, Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG) has been endemic longer (20–25 years, lighter symbols and shading, dotted line) were more tolerant of experimental infection than house finch populations with little or no history of MG endemism with both (a) an evolutionarily basal, lower-virulence MG isolate (n = 141 birds from 7 populations) and (b) an evolutionarily derived, higher-virulence isolate (n = 61 birds from 6 populations). We quantified tolerance as the ability to maintain health (y-axis, lower maximum conjunctivitis scores) despite increasing pathogen loads (x-axis; log10(maximum pathogen load + 1)). The most pronounced difference we detected in resistance, measured as lower log10(maximum pathogen load + 1), was within the low-dose, low-virulence treatment, between populations with 0–10 years of pathogen endemism (dark triangles) and those with 10–20 years of pathogen endemism (medium-shaded triangles). For the low-virulence isolate (a), we used data collected from the same individuals both pre-infection and at post-infection peaks in pathogen load and conjunctivitis scores following either a low- or high-dose inoculation (7.5x102 and 7.5x106 CCU/mL, respectively). For high-virulence infections (b), we performed analyses similarly, but used only the 7.5x102 CCU/mL inoculation dose (see main text). Lines show predictions from generalized linear mixed effects models with shading representing bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Data have been jittered in the graph to clearly visualize all points.