Abstract

Advanced systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) can be treated with lung transplantation. There is limited data on lung transplantation outcomes in patients with SSc-ILD, in non-Western populations.We assessed survival data of patients with SSc-ILD, on the lung transplant (LT) waiting list, and evaluated post-transplant outcomes in patients from an Asian LT center. In this single-center retrospective study, 29 patients with SSc-ILD, registered for deceased LT at Kyoto University Hospital, between 2010 and 2022, were identified. We investigated post-transplant outcomes in recipients who underwent LT for SSc-ILD, between February 2002 and April 2022. Ten patients received deceased-donor LT (34%), two received living-donor LT (7%), seven died waiting for LT (24%), and ten survived on the waiting list (34%). Median duration from registration to deceased-donor LT was 28.9 months and that from registration to living-donor LT or death was 6.5 months. Analysis of 15 recipients showed improved forced vital capacity with a median of 55.1% at baseline, 65.8% at 6 months, and 80.3% at 12 months post-transplant. The 5-year survival rate for post-transplant patients with SSc-ILD was 86.2%. The higher post-transplant survival rate at our institute than previously reported suggests that lung transplantation is acceptable in Asian patients with SSc-ILD.

Subject terms: Connective tissue diseases, Systemic sclerosis

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by microangiopathy and fibrosis affecting the skin and visceral organs. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a major complication and the leading cause of death in SSc, accounting for 35% of SSc-related deaths1. SSc-associated ILD (SSc-ILD) is a mortality risk factor for patients with SSc2. Although recent studies have shown that several immunosuppressants, such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and nintedanib (an anti-fibrotic agent), can reduce the rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) in progressive SSc-ILD, there is no evidence-based pharmacological therapy that improves survival and reverses extensive lung damage3–5.

Lung transplantation is a potentially life-saving intervention for selected patients with severe ILD refractory to medical therapy6,7. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a progressive type of ILD, is a widely accepted indication for lung transplantation7. However, several centers have been reluctant to offer lung transplants to patients with SSc-ILD and other connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated ILD (CTD-ILD). This is due to concern for worse post-transplant outcomes associated with extrapulmonary CTD manifestations7,8. Although recent studies have shown similar outcomes for lung transplantation in patients with IPF and SSc-ILD, more research is needed to determine the safety and efficacy of the transplant approach for SSc-ILD9–12.

The 2021 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) consensus document proposed that lung transplantation is an acceptable treatment for selected patients with CTD, including advanced SSc-ILD13. However, there are no reports of lung transplantation in patients with SSc-ILD from non-Western countries. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prognosis of patients with SSc-ILD on the lung transplant waiting list and evaluate post-transplant outcomes for patients attending a lung transplant center in Asia.

Materials & methods

Study participants

Using a lung transplant candidate database, patients with SSc-ILD who were registered for deceased-donor lung transplantation at the Kyoto University Hospital between April 2010 and April 2022 were identified. The diagnosis of SSc was made by rheumatologists based on the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria of 1980 or the ACR/European League Against Rheumatism criteria of 201314,15. The registration criteria for the nationwide Japan Organ Transplant Network (JOTN) are: (1) fulfilling the international listing criteria for lung transplantation and (2) age < 60 years for a single lung transplant and < 55 years for a bilateral lung transplant at the time of registration16–18. The international listing criteria for lung transplants in patients with ILD are: (1) a rapid decline in pulmonary function over six months, (2) hypoxia, (3) decreased walking distance on the 6-min walk test, (4) pulmonary hypertension (PH), and (5) previous hospitalization due to an acute event (e.g. pneumothorax and acute exacerbation)16,17,19. Patients who fulfill one or more of these items are registered on JOTN as candidates for a deceased-donor lung transplant. The algorithm for deceased-donor lung allocation is based primarily on the time the patient has been on the waiting list. In Japan, due to the shortage of donors, single lung transplantation is the standard procedure used for deceased-donor lung transplants for ILDs, including SSc-ILD and IPF. Bilateral deceased-donor lung transplants are warranted only in cases of active chronic respiratory infection, severe PH, and refractory bilateral pneumothorax. Living-donor lung transplants are an option for selected patients with two voluntary donors if the patient cannot continue waiting for a deceased-donor lung transplant due to the severity of their condition20.

Patients aged < 18 years at the time of registration and those registered for re-transplantation were excluded from the study. In addition, to investigate post-transplant outcomes, recipients who underwent lung transplantation (deceased or living donor) for SSc-ILD or IPF at Kyoto University Hospital between February 2002 and April 2022 were identified from the lung transplant recipient database.

Clinical variables

Clinical variables included in the analysis were patient demographics, body mass index, smoking history, distance in the six-minute walk test, SSc subtypes, organ involvement other than ILD, autoantibody profile, the extent of CT involvement, pulmonary function test results (PFT), previous treatments, and long-term oxygen therapy usage. These baseline parameters were obtained at the time of evaluation for lung transplantation. About the evaluation of CT involvement, the extensive disease was defined based on the Goh’s criteria21. For other organ involvement, PH was diagnosed if (1) estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (ePASP) on transthoracic echocardiogram was 40 mmHg or more or (2) mean pulmonary arterial pressure on right heart catheterization was 25 mmHg or more. Gastrointestinal involvement, such as esophageal dilatation, esophageal motility disorder, or gastroesophageal reflux disease, was screened prior to lung transplantation using upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), if possible.

Post-transplant evaluation

All lung transplant recipients underwent PFT at 3, 6, and 12 months post-transplant. They also underwent HRCT pre-transplant and post-transplant at either 3 or 6 months and 12 months. After 12 months, the recipients underwent PFT and HRCT every 12 months. The PFT results at the initial evaluation for a lung transplant and those at 6 and 12 months post-transplant were used to evaluate changes in functional impairment.

HRCT images were reviewed under blind conditions by two observers (TH and KT). Pre-and post-transplant HRCT scans were examined for evidence of relapse in the transplant lungs and changes in the native lungs (deterioration, no change, or improvement). In addition, all available post-transplant HRCT images were examined.

Statistical analyses

The Mann–Whitney U and the Fisher’s exact tests were used for group comparisons. A paired t test was used to analyze serial changes in individual patients. Survival time on the waiting list for deceased-donor lung transplants was calculated from the registration date until the patient’s death or living-donor lung transplant. Patients were right-censored at the time of the deceased-donor lung transplant or the last contact. The last observational date was 30 April 2022. A living-donor lung transplant was counted as an event as it represented the emergence of a fatal condition. The cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to identify the factors predictive of mortality on the waiting list. The post-transplant survival time was calculated from the date of the lung transplant to the patient’s death, with patients right-censored at the date of re-transplantation (including the second transplantation for the residual native lung) or the last contact prior to 30 April 2022. Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to demonstrate and compare the survival time post-transplant between the SSc-ILD and IPF groups. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)22. All analyses were two-tailed, and a P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

All study participants provided informed consent, and the study design was approved by the appropriate ethics review board. Therefore, this observational study (not being a clinical trial) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board (Kyoto University approval number R1355, R1353, R2401).

Results

Characteristics and prognosis of patients with SSc-ILD registered for deceased-donor lung transplantation

Twenty-nine patients with SSc-ILD registered for deceased-donor lung transplants between April 2010 and April 2022 (Table 1). Of these, ten patients received deceased-donor lung transplants (34%), two received living-donor lung transplants (7%), seven died while waiting for a lung transplant (24%), and the remaining ten survived on the list (34%) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The median waiting time from registration to deceased-donor lung transplant was 28.9 months (range 22.3–30.3). The median duration from registration to living-donor lung transplant or death (events) was 6.5 months (range 4.1–14.7).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease patients registered on lung transplantation waiting list.

| Patients (N = 29) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (S.D.) | 47.2 (9.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 18 (62) |

| Disease duration (Y), median (IQR) | 7.0 [5.1, 12.3] |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 21.9 [19.4, 24.8] |

| (Ex-)smokers, n (%) | 16 (55) |

| 6MWD (m), median (IQR) | 355 [251, 485] |

| SSc subtypes | |

| lcSSc, n (%) | 14 (48) |

| dcSSc, n (%) | 15 (52) |

| Symptoms/complications of SSc | |

| Raynaud phenomenon, n (%) | 27 (93) |

| Digital ulcer, n (%) | 2 (7) |

| PH, n (%) | 14 (48) |

| GI involvementa, n (%) | 20 (69) |

| SRC history, n (%) | 1 (3) |

| Treatment | |

| PSL, n (%) | 25 (86) |

| PSL dose (mg), median (IQR) | 10 [5, 15] |

| Calcineurin inhibitors, n (%) | 10 (34) |

| IVCY (previous use), n (%) | 11 (38) |

| Nintedanib, n (%) | 6 (21) |

| Autoantibodies | |

| ACA, n (%) | 3 (12) |

| ATA, n (%) | 15 (56) |

| RNA polymerase-III, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| U1-RNP, n (%) | 4 (15) |

| Extensive CT involvementb, n (%) | 22 (76) |

| Spirogram | |

| % FVC, median (IQR) | 51.1 [44.7, 57.4] |

| % DLCO, median (IQR) | 28.6 [21.8, 35.1] |

| LTOT, n (%) | 23 (79) |

| Outcomes | |

| Deceased-donor transplant | 10 (34) |

| Living-donor transplant | 2 (7) |

| Died awaiting transplant | 7 (24) |

| Alive on the waiting list | 10 (34) |

6MWD Six-minute walk distance, ACA anti-centromere antibody, ATA anti-topoisomerase-1 antibody, dcSSc diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, DLCO diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, FVC forced vital capacity, GI gastrointestinal, ILD interstitial lung disease, IQR interquartile range, IVCY intravenous cyclophosphamide, lcSSc limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis, LTOT long-term oxygen therapy, PH pulmonary hypertension, PSL prednisolone, RNA ribonucleic acid, RNP ribonucleoprotein, S.D. standard deviation, SRC scleroderma renal crisis, SSc systemic sclerosis, Y year/s.

aGastrointestinal involvement included esophageal dilatation, esophageal motility disorder, and gastroesophageal reflux disease detected using gastrointestinal endoscopy or computed tomography.

bExtensive CT involvement was defined based on the Goh’s criteria (the total disease extent in high-resolution CT > 20% was determined as ‘extensive’).

Of the patients with SSc-ILD registered for a deceased-donor lung transplant, characteristics of the patients who received a deceased-donor lung (n = 10), a living-donor lung, or those who died on the waiting list (n = 9) are compared in Table 2 to identify associated factors of a worse outcome. PH was more common in patients receiving living-donor lungs and those who died on the waiting list. It was also associated with mortality and switching to living-donor lung transplantation while waiting for a deceased-donor lung (hazard ratio: 10.1; 95% confidence interval: [1.26–81.1], P < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease patients with deceased/living-donor or who died awaiting transplant.

| Deceased-donor lung transplant (N = 10) | Living-donor lung transplant or died awaiting transplant (N = 9) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (S.D.) | 45.8 (3.1) | 47.8 (3.3) | 0.67 |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (60) | 6 (67) | 0.76 |

| Disease duration (Y), median (IQR) | 6.4 [1.2, 13.1] | 8.0 [4.0, 9.7] | 0.46 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 21.5 [20.5, 24.0] | 21.2 [15.3, 22.8] | 0.41 |

| (Ex-)smokers, n (%) | 7 (70) | 5 (56) | 0.51 |

| 6MWD (m), median (IQR) | 342 [251, 459] | 263 [151, 305] | 0.16 |

| SSc subtypes, lcSSc(n)/dcSSc(n) | 6/4 | 5/4 | 0.84 |

| Symptoms/complications of SSc | |||

| Raynaud phenomenon, n (%) | 10 (100) | 9 (100) | NA |

| Digital ulcer, n (%) | 1 (10) | 1 (11) | 0.93 |

| PH, n (%) | 3 (30) | 8 (89) | 0.009 |

| GI involvementa, n (%) | 7 (70) | 6 (67) | 0.88 |

| SRC history, n (%) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.33 |

| Treatment | |||

| PSL, n (%) | 8 (80) | 9 (100) | 0.16 |

| PSL dose (mg), median (IQR) | 10 [3, 15] | 10 [6, 15] | 0.66 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors, n (%) | 5 (50) | 2 (22) | 0.21 |

| IVCY (previous use), n (%) | 3 (30) | 4 (44) | 0.51 |

| Nintedanib, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0.28 |

| Autoantibodies | |||

| ACA, n (%) | 0 (0 | 1 (13) | 0.33 |

| ATA, n (%) | 5 (50) | 2 (25) | 0.20 |

| RNA polymerase-III, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| U1-RNP, n (%) | 2 (25) | 2 (22) | 0.89 |

| Extensive CT involvementb, n (%) | 9 (90) | 7 (78) | 0.47 |

| Spirogram | |||

| %FVC, median (IQR) | 56.6 [52.9, 65.7] | 47.8 [34.9, 55.6] | 0.10 |

| %DLCO, median (IQR)c | 23.7 [21.3, 25.0] | 33.9 [18.4, 36.1] | 0.46 |

| LTOT, n (%) | 9 (90) | 9 (100) | 0.33 |

| Duration from registration date to outcome date (M), median (IQR) | 28.9 [22.3, 30.3] | 6.5 [4.1, 14.7] | < 0.001 |

6MWD Six-minute walk distance, ACA anti-centromere antibody, ATA anti-topoisomerase-1 antibody, dcSSc diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, DLCO diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, FVC forced vital capacity, GI gastrointestinal, IQR interquartile range, IVCY intravenous cyclophosphamide, lcSSc limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis, LTOT long-term oxygen therapy, M month/s, PH pulmonary hypertension, PSL prednisolone, RNA ribonucleic acid, RNP ribonucleoprotein, S.D. standard deviation, SRC scleroderma renal crisis, SSc systemic sclerosis, Y year/s.

aGastrointestinal involvement included esophageal dilatation, esophageal motility disorder, and gastroesophageal reflux disease detected using gastrointestinal endoscopy or computed tomography.

bExtensive CT involvement was defined based on Goh’s criteria (the total disease extent in high-resolution CT > 20% was determined as “extensive”).

cBecause of low vital capacity, there were three missing data points from the deceased-donor lung transplant group and four missing from the living-donor lung transplant or died awaiting transplant group.

Table 3.

Risk factors for death or living-donor transplantation while awaiting deceased-donor lung transplantation.

| Univariate cox model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.95–1.09 | 0.82 |

| Sex, male | 0.65 | 0.16–2.60 | 0.53 |

| BMI | 0.85 | 0.71–1.00 | 0.056 |

| 6MWD (m), median (IQR) | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.054 |

| PH | 10.1 | 1.26–81.1 | 0.0049 |

| % FVC | 0.97 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.31 |

| % DLCO | 1.00 | 0.89–1.11 | 0.99 |

6MWD Six-minute walk distance, BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, DLCO diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, FVC forced vital capacity, HR hazard ratio, PH pulmonary hypertension.

Outcomes of lung transplantation for patients with SSc-ILD

Fifteen patients received a lung transplant for SSc-ILD between February 2002 and April 2022; three patients underwent a deceased-donor bilateral lung transplant, seven underwent a deceased-donor single lung transplant, four had a living-donor bilateral lung transplant, and one had a living-donor single lung transplant (Supplementary Fig. S1). In addition, three patients received a living-donor lung transplant without registration for a deceased-donor lung transplant. Individual lung transplant cases are summarized in Table 4. All recipients were managed with a combination of corticosteroids (maintenance dose: prednisolone 0.2 mg/kg every two days), calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine A or tacrolimus), and mycophenolate mofetil as the standard regimen of post-transplant immunosuppression.

Table 4.

Description of systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease patients who underwent deceased- or living-donor lung transplantation.

| No | Age | Sex | Autoantibody | Transplant type | Wait time (mo) | PH | GI involvementa | LTOT pre-transplant | Outcomes | Follow-up post-transplant (mo) | LTOT post-transplant | ILD relapse in transplanted lungs | ILD exacerbations in residual lungs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42.7 | M | ANA, ATA | Deceased (B) (due to PH) | 30 | + | + | + | Alive | 71 | – | – | (No residual) |

| 2 | 25.4 | F | ANA | Deceased (B) (due to recurrent bilateral pneumothorax) | 29 | – | + | + | Alive | 58 | – | – | (No residual) |

| 3 | 52.9 | F | ANA, ATA, U1-RNP | Deceased (B) (due to chronic lung infection) | 30 | – | + | + | Dead (sepsis) | 62 | (Dead) | – | (No residual) |

| 4 | 61.9 | F | ANA | Deceased (S) | 28 | – | + | – | Alive | 26 | – | – | – |

| 5 | 58.7 | F | ANA, U1-RNP | Deceased (S) | 17 | + | – | + | Alive | 96 | + | – | + |

| 6 | 31.8 | F | ANA, ATA | Deceased (S) | 18 | – | + | + | Re-transplantation for bilateral lungs (living-donor (B)) | 47 | (Retransplant) | – | – |

| 7 | 48.1 | M | ANA, ATA | Deceased (S) | 30 | + | + | + | Alive | 42 | – | – | – |

| 8 | 54.7 | M | ANA | Deceased (S) | 25 | – | + | + | Dead (CLAD) | 25 | (Dead) | – | + |

| 9 | 49.2 | F | ANA | Deceased (S) | 25 | – | + | + | Alive | 31 | – | – | – |

| 10 | 59.3 | M | ANA, ATA | Deceased (S) | 37 | + | + | + | Alive | 47 | – | – | – (improved) |

| 11 | 59.4 | M | ANA | Living donor (B) | – | + | + | + | Alive | 86 | – | – | – |

| 12 | 54.8 | F | None | Living donor (B) | – | + | – | + | Alive | 163 | – | – | (No residual) |

| 13 | 57.8 | F | ANA | Living donor (B) | 4 | – | – | – | Dead (sepsis) | 8 | (Dead) | – | (No residual) |

| 14 | 56.0 | F | ANA, ACA | Living-donor (B) | 11 | + | + | + | Alive | 8 | – | – | (No residual) |

| 15 | 43.8 | F | ANA, ATA | Living donor (S) | – | + | – | + | Re-transplantation for the contralateral native lung (deceased (S)) | 35 | (Retransplant) | – | + |

– absent, + present, ACA anti-centromere antibody, ANA anti-nuclear antibody, ATA anti-topoisomerase I antibody, B bilateral lung transplantation, CLAD chronic lung allograft dysfunction, F female, GI gastrointestinal, ILD interstitial lung disease, LTOT long-term oxygen therapy, M male, mo month/s, PH pulmonary hypertension, RNP ribonucleoprotein, S single lung transplantation.

aGastrointestinal involvement included esophageal dilatation, esophageal motility disorder, and gastroesophageal reflux disease detected using gastrointestinal endoscopy or computed tomography.

During the median post-transplant observation time of 47 months (range 26–71), three of the fifteen lung transplant recipients with SSc-ILD died (20%). One patient died of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), and two died of sepsis. Two patients received a second lung transplant after a single lung transplant. One patient (patient No.6) developed CLAD after a deceased-donor lung transplant. They underwent a further living-donor bilateral lung transplant 47 months after their initial transplant. Another patient (patient No.15) developed CLAD in their transplanted lung and had disease progression in their native lung. They underwent a deceased-donor right lung transplant 35 months after their initial living-donor left lung transplant. This patient had undergone their initial living-donor single lung transplant as an emergency measure as a deceased-donor lung was unavailable. Three patients in total were diagnosed with CLAD (20%). The estimated 1-year and 5-year post-transplant survival rates (re-transplantation-censored) from the time of lung transplantation were 93.3% and 86.2%, respectively. Post-transplant survival was similar in the bilateral and single lung transplant groups (log-rank test, P = 0.46).

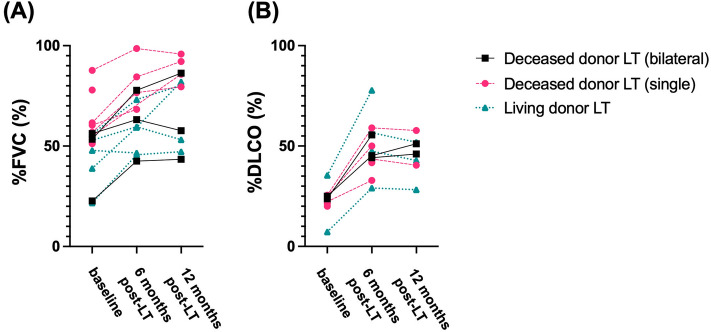

The PFT results from 6 and 12 months post-transplantation were obtained for 15 patients. Changes in %FVC from pre-transplant to 6 and 12 months post-transplant are shown in Fig. 1A. In all patients, the median %FVC was 55.1% (interquartile range [IQR] 47.8–60.4%) pre-transplantation and improved to 65.8% (IQR 49.8–77.5%) at 6 months and 80.3% (IQR 53.2–86.3%) at 12 months post-transplant. Nine patients (69%) were free from long-term oxygen therapy use 6 months post-transplant. Changes in % diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) from pre-transplant to 6 and 12 months post-transplant are shown in Fig. 1B. In all patients, the median % DLCO was 23.7% (IQR 20.7–25.3%) pre-transplantation and improved to 46.4% (IQR 42.1–56.4%) at 6 months and 46.0% (IQR 40.5–51.9%) at 12 months post-transplant.

Figure 1.

(A) Changes in forced vital capacity (%) from the baseline (pre-transplant) to 6 and 12 months post-transplant. FVC forced vital capacity, LT lung transplantation. (B) Changes in diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (%) from the baseline (pre-transplant) to 6 and 12 months post-transplant. DLCO diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

The pre-transplant and post-transplant data of ePASP on transthoracic echocardiogram were obtained for patients who had pulmonary hypertension before LT. The median ePASP was 56 mmHg (IQR 46-77 mmHg) before LT and decreased to 37 mmHg (IQR 24-41 mmHg) at six months post-transplant.

During the post-transplant period (median 47 months, range 26–71), there was no ILD relapse in the transplanted lungs. A renal crisis was not observed for any patient. Disease progression in the native lung on HRCT was observed in three of the eight single lung transplant recipients.

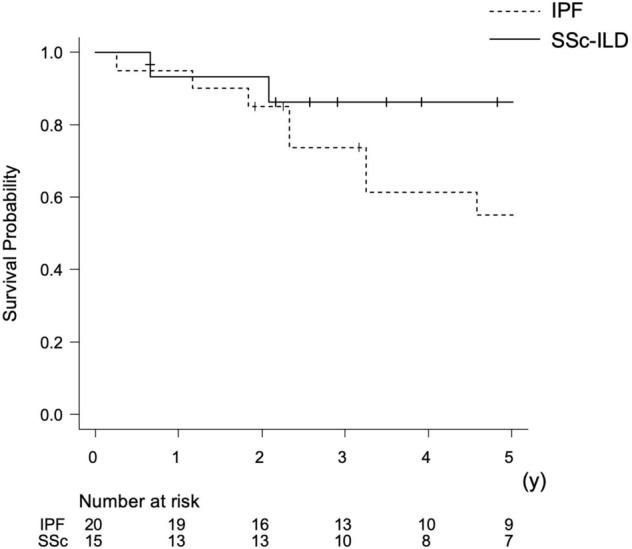

Comparison of post-transplant outcomes between patients with SSc-ILD and IPF

Fifteen patients with SSc-ILD and twenty with IPF (diagnosed through multidisciplinary discussions) underwent lung transplantation between February 2002 and April 2022. Of the 20 cases of IPF, 11 (55%) were deceased-donor single lung transplants, and nine (45%) were living-donor bilateral lung transplants. The baseline characteristics of recipients with SSc-ILD and IPF are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Patients in the IPF group were less likely to be female than male, had a lower incidence of PH, and had a lower prednisolone use rate. During the post-transplant period (median 47 months, range 26–71), eight of the twenty recipients with IPF died, and none received re-transplantation. The estimated 5-year post-transplant survival rate (re-transplantation-censored) was 55.3% in the IPF group and 86.2% in the SSc-ILD group (P = 0.33) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The estimated 5-year post-transplant survival curves (re-transplantation-censored) post-transplant in patients with systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. IPF idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, SSc-ILD systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease.

Discussion

In this study, 34% of patients with SSc-ILD on the waiting list received a deceased-donor lung transplant after a median wait time of 28.9 months. A total of 31% of patients on the wait list died or required a living-donor lung transplant as an emergency treatment. Lung transplantation improved pulmonary function and led to the cessation of long-term oxygen therapy in approximately 70% of patients, with no relapse of SSc-ILD in the transplanted lungs and no serious deterioration of extrapulmonary manifestations post-transplant. Post-transplant survival for patients with SSc-ILD was comparable to those with IPF.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the outcomes of patients with SSc-ILD registered for deceased-donor lung transplants. Similar studies of patients with IPF on the waiting list for deceased-donor lung transplants showed that 40–60% of patients died while awaiting transplants23–27. We recently reported that in a study of 166 patients on the transplant waiting list (who had ILDs, including SSc-ILD, IPF, and other ILDs), 33% of these patients received a deceased-donor lung transplant19. Another study from a single institute in Japan showed lower mortality rates for patients with non-IPF ILD (57.9% of patients with CTD) than those with IPF, 40.4% vs 61.4%, respectively27. Our results (deceased-donor lung transplant in one-third of patients and mortality or a living-donor lung transplant in another third) were comparable with the reported outcomes of patients with IPF and other ILDs on the waiting list for a deceased-donor lung transplant in Japan. Thus, registration for deceased-donor lung transplants should be considered for patients with severe SSc-ILD at an appropriate time, as well as for those with IPF and other ILDs.

Approximately one-third of patients with SSc-ILD died or needed living-donor lung transplants as an emergency treatment, if available, during the waiting time for a deceased-donor lung transplant. PH was predictive of these fatal outcomes. The combination of ILD and PH in SSc has been associated with a worse prognosis than ILD or PH alone28,29. The 2021 ISHLT consensus document proposed three pulmonary phenotypes of SSc in lung transplant candidates according to the extent of ILD and hemodynamic profiles: predominant ILD, combined ILD-PH, and predominant PH13. Earlier waitlisting for a deceased-donor lung transplant may be advisable if a patient with SSc has a combined ILD-PH phenotype.

In 2021, the ISHLT proposed lung transplantation was an acceptable option for selected patients with advanced CTD-ILD, including SSc-ILD, after a long-standing debate lasting decades13. Particular concerns for patients with SSc-ILD include an increased risk of CLAD associated with esophageal dysmotility and, consequently, a worse post-transplant survival rate than other ILDs16,30. However, high-volume lung transplant centers in both the US and Europe have consistently reported acceptable outcomes of lung transplantation for SSc,the estimated 1-year survival rates post-transplant were 81–100%, and the 5-year survival rates were 61–76%9–11,31–33. The risk of CLAD was similar between lung transplants for SSc and those for other ILDs. Esophageal disease in SSc did not affect post-transplant survival compared with lung transplants for recipients with other ILDs11,31,32. Our results are consistent with previous reports from the US and European lung transplant centers and support the 2021 ISHLT proposal. This study is the first lung transplantation report in cases of SSc-ILD from a high-volume center in Asia. The estimated 5-year post-transplant survival rate was higher than previous reports from other countries, suggesting that favorable post-transplant outcomes can also be achieved in non-Western high-volume lung transplant centers.

The potential effects of the underlying autoimmune condition on the transplanted tissue have been postulated for SSc and other CTD-ILDs31,33. In our study, there was no relapse of ILD in the transplanted lung, although ILD in the native lung was progressive for some patients who received a single lung transplant. No serious extrapulmonary complications associated with SSc, such as renal crisis or bowel pseudo-obstruction, were noted. The 2021 ISHLT consensus document listed cardiac, venous thromboembolism, renal (renal crisis), gastrointestinal, and vascular (Raynaud’s phenomenon) involvement as disease-specific extrapulmonary manifestations that require consideration and evaluation prior to lung transplantation for SSc13. Although the previous 2014 ISHLT criteria for lung transplantation did not include disease-specific listing criteria for SSc-ILD16, patients with either active or uncontrolled extrapulmonary manifestations, severe swallowing/esophageal dysfunction, and active myocarditis were excluded from the registry for lung transplantation. Thus, if transplant candidates are carefully selected, lung transplantation for SSc-ILD can be performed with minimal risk of exacerbating extrapulmonary manifestations. Evaluating extrapulmonary manifestations based on a protocol may facilitate the selection of appropriate transplant candidates and thus improve the post-transplant outcomes of recipients with SSc-ILD.

The functional benefits obtained from lung transplantation, post-transplant survival, and risks should be considered. Our results suggest short-term improvement and maintenance of pulmonary function after lung transplant for patients with SSc-ILD, as shown in Fig. 1. Additionally, more than 60% of patients ceased long-term oxygen therapy post-transplant.

Bilateral lung transplant is the preferred procedure for patients with CTD-ILD because of the theoretical benefit of improved survival and post-operative right ventricular function and better reserve to compensate for any decline in lung function due to CLAD34. Despite evidence supporting the superiority of bilateral lung transplantation, single lung transplants are still utilized in some countries and lung transplant centers34. In Japan, bilateral lung transplants are restricted to patients with active chronic infection, severe PH, or refractory pneumothorax due to the shortage of deceased donors. About half of the recipients in our cohort received a single lung transplant for SSc-ILD, with similar post-transplant outcomes between bilateral and single procedures. ILD progression in the native lung was observed over time in one-third of the single lung transplant recipients. Post-transplant changes in the native lung may influence long-term outcomes after single lung transplantation35,36. The impact of transplant procedures (bilateral vs single) and ILD progression in the native lung (following a single lung transplant) on post-transplant outcomes should be addressed in a larger cohort.

This study had limitations in terms of generalizability. The number of transplant candidates for SSc-ILD was insufficient to investigate the predictors of fatal outcomes on the waiting list. The high frequency of single lung transplants in Japan may have a significant effect on the waiting time for transplants37. A single-institution study design may also have biased the post-transplant outcomes. Although the 2021 ISHLT consensus paper proposed the need for hemodynamic profiles in lung transplant candidates for SSc, only a few patients underwent right heart catheterization pre-transplant13.

Conclusions

Using data from one of the highest-volume lung transplant centers in a non-Western country, we showed that lung transplantation could be an acceptable treatment for selected patients with severe SSc-ILD. Lung transplant indications for SSc and the appropriate time for referral to lung transplant centers should be determined individually in a disease-specific manner.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage [http://www.editage.com] for editing and reviewing this manuscript for English language.

Abbreviations

- SSc

Systemic sclerosis

- ePASP

Estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure

- CLAD

Chronic lung allograft dysfunction

- IQR

Interquartile range

- DLCO

Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

- PFT

Pulmonary function test results

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- HRCT

High-resolution computed tomography

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- PH

Pulmonary hypertension

- ISHLT

International society for heart and lung transplantation

- CTD

Connective tissue disease

Author contributions

Y.N., R.N., T.H., A.O. and K.T. conceived the idea of the study. Y.N. and R.N. developed the statistical analysis plan and conducted statistical analyses. Y.N., R.N., T.H., A.O. and K.T. contributed to the interpretation of the results. Y.N. and R.N. drafted the original manuscript. Y.Yu., D.K., Y.Ya., S.T., S.H., K.I., M.S., R.H., H.T., K.K., S.A., H.Y., H.D., M.A. and other authors substantially contributed to the revision of the manuscript drafts. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. Informed consents were obtained from from all subjects for publication of this study.

Funding

No specific funding was received from public, commercial, or not-for-profit bodies to carry out the work described in this article.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

RN has collaborated with Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd. and has received speaking fees from Astellas Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Asahi Kasei, Japan Blood Products Organization, and Nihon Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. HY has received a lecture fee from Chugai, Janssen, and Boehringer Ingelheim outside of this work. YN, TH, AO, YYamada, DN, YYutaka, ST, SH, KI, KT, MS, RH, HT, KK, SA, HD, and AM declare no potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-37141-w.

References

- 1.Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, Airò P, Cozzi F, Carreira PE, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: A study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010;69:1809–1815. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.114264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hax V, Bredemeier M, Didonet Moro AL, Pavan TR, Vieira MV, Pitrez EH, et al. Clinical algorithms for the diagnosis and prognosis of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, Lees B, Newlands P, Goh NSL, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3962–3970. doi: 10.1002/art.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liossis SNC, Bounas A, Andonopoulos AP. Mycophenolate mofetil as first-line treatment improves clinically evident early scleroderma lung disease. Rheumatology. 2006;45:1005–1008. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, Azuma A, Fischer A, Mayes MD, et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thabut G, Mal H, Castier Y, Groussard O, Brugière O, Marrash-Chahla R, et al. Survival benefit of lung transplantation for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2003;126:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Natalini JG, Diamond JM, Porteous MK, Lederer DJ, Wille KM, Weinacker AB, et al. Risk of primary graft dysfunction following lung transplantation in selected adults with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.01.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JC, Ahya VN. Lung transplantation in autoimmune diseases. Clin. Chest Med. 2010;31:589–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan EY, Goodarzi A, Sinha N, Nguyen DT, Youssef JG, Suarez EE, et al. Long-term survival in bilateral lung transplantation for scleroderma-related lung disease. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018;105:893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miele CH, Schwab K, Saggar R, Duffy E, Elashoff D, Tseng CH, et al. Lung transplant outcomes in systemic sclerosis with significant esophageal dysfunction. A comprehensive single-center experience. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016;13:793–802. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201512-806OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crespo MM, Bermudez CA, Dew MA, Johnson BA, George MP, Bhama J, et al. Lung transplant in patients with scleroderma compared with pulmonary fibrosis. Short- and long-term outcomes. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016;13:784–92. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-177OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minalyan A, Gabrielyan L, Khanal S, Basyal B, Derk C. Systemic sclerosis: Current state and survival after lung transplantation. Cureus. 2021;13:e12797. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crespo MM, Lease ED, Sole A, Sandorfi N, Snyder LD, Berry GJ, et al. ISHLT consensus document on lung transplantation in patients with connective tissue disease: Part I: Epidemiology, assessment of extrapulmonary conditions, candidate evaluation, selection criteria, and pathology statements. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:1251–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masi AT. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2737–2747. doi: 10.1002/art.38098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, Dark JH, Davis RD, Keshavjee S, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014–an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, Conte JV, Corris P, Egan JJ, et al. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update–a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maurer JR, Frost AE, Estenne M, Higenbottam T, Glanville AR. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, the American Thoracic Society, the American Society of Transplant Physicians, the European Respiratory Society. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:703–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagata S, Ohsumi A, Handa T, Yamada Y, Tanaka S, Yutaka Y, et al. Assessment of listing criteria for lung transplant candidates with interstitial lung disease. Gen. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023;71:20–26. doi: 10.1007/s11748-022-01861-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajima D, Date H. Living-donor lobar lung transplantation. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021;13:6594–6601. doi: 10.21037/jtd-2021-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh NSL, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: A simple staging system. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;177:1248–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett D, Fossi A, Bargagli E, Refini RM, Pieroni M, Luzzi L, et al. Mortality on the waiting list for lung transplantation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A single-centre experience. Lung. 2015;193:677–681. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Oliveira NC, Julliard W, Osaki S, Maloney JD, Cornwell RD, Sonetti DA, et al. Lung transplantation for high-risk patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;33:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikezoe K, Handa T, Tanizawa K, Chen-Yoshikawa TF, Kubo T, Aoyama A, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes in Japanese lung transplant candidates with interstitial lung disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyahara S, Waseda R, Tokuishi K, Sato T, Iwasaki A, Shiraishi T. Elucidation of prognostic factors and the effect of anti-fibrotic therapy on waitlist mortality in lung transplant candidates with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respir. Investig. 2021;59:428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2021.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirama T, Akiba M, Watanabe T, Watanabe Y, Notsuda H, Oishi H, et al. Waiting time and mortality rate on lung transplant candidates in Japan: A single-center retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021;21:390. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01760-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefèvre G, Dauchet L, Hachulla E, Montani D, Sobanski V, Lambert M, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2412–2423. doi: 10.1002/art.38029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young A, Vummidi D, Visovatti S, Homer K, Wilhalme H, White ES, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of coexistent pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1339–1349. doi: 10.1002/art.40862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tangaroonsanti A, Lee AS, Crowell MD, Vela MF, Jones DR, Erasmus D, et al. Impaired esophageal motility and clearance post-lung transplant: Risk for chronic allograft failure. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2017;8:e102. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2017.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saggar R, Khanna D, Furst DE, Belperio JA, Park GS, Weigt SS, et al. Systemic sclerosis and bilateral lung transplantation: A single centre experience. Eur. Respir. J. 2010;36:893–900. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00139809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sottile PD, Iturbe D, Katsumoto TR, Connolly MK, Collard HR, Leard LA, et al. Outcomes in systemic sclerosis-related lung disease after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95:975–980. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182845f23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein EJ, Peterson ER, Sell JL, D’Ovidio F, Arcasoy SM, Bathon JM, et al. Survival of adults with systemic sclerosis following lung transplantation: A nationwide cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1314–1322. doi: 10.1002/art.39021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bermudez CA, Crespo MM, Shlobin OA, Cantu E, Mazurek JA, Levine D, et al. ISHLT consensus document on lung transplantation in patients with connective tissue disease: Part II: Cardiac, surgical, perioperative, operative, and post-operative challenges and management statements. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez FJ, Alvarez E, Moreno P, Poveda D, Ruiz E, Fernandez AM, et al. The influence of the native lung on early outcomes and survival after single lung transplantation. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0249758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.King CS, Khandhar S, Burton N, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, Lefrak E, et al. Native lung complications in single-lung transplant recipients and the role of pneumonectomy. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Japanese Society of Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Registry report of Japanese lung transplantation 2020. Transplantation. 2020;55:271–276. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.