Abstract

Gomisin C is a lignan isolated from the fruit of Schisandra chinensis. The current study aimed to investigate the effect of gomisin C on lipid accumulation in adipocytes and its underlying mechanism. Gomisin C effectively inhibited lipid accumulation by downregulating adipogenic factors such as PPARγ and C/EBPα. Gomisin C-mediated suppression of lipid accumulation occurred in the early adipogenic stage; C/EBPβ was downregulated by 55%, while KLF2 was upregulated by 1.5-fold. Gomisin C significantly reduced the production of reactive oxygen species but upregulated antioxidant enzymes, including catalase, SOD1, and Gpx at the mRNA level. Gomisin C regulated NRF2-KEAP1 pathway by increasing NRF2 and decreasing KEAP1, in protein abundance. Furthermore, gomisin C suppressed the JAK2-STAT signaling pathway by decreasing phosphorylation. Taken together, gomisin C reduced early adipogenesis and ROS production by inhibiting the JAK2-STAT signaling pathway but activating the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling pathway.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-023-01263-8.

Keywords: Gomisin C, 3T3-L1, Lipid accumulation, JAK2-STAT signaling, NRF2-KEAP1 signaling

Introduction

Schisandra chinensis Turcz. (Baill.) is a vine that grows naturally in East Asia, including China, Russia, Korea, and Japan (Szopa et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2022). Its fruit is called five-flavor fruit (Omija) as it produces five kinds of tastes: salty, sweet, sour, pungent (spicy), and bitter (Szopa et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2022). The fruit of this vine has long been used as a traditional medicine in eastern countries (Szopa et al., 2017). Schisandra chinensis contains various compounds classified as dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans, including gomisin A, B, and N, and schisandrin A, B, and C (Szopa et al., 2017). The extracts or compounds of S. chinensis have been reported to demonstrate various pharmacological effects, such as cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer (Chen et al., 2019; Chun et al., 2014; Dai et al., 2018). Several studies have reported that S. chinensis-derived compounds suppress lipid accumulation and obesity in vitro and in vivo (Jang et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021). However, the effects of gomisin C (GC) on lipid accumulation and its mechanisms have rarely been studied.

Adipocyte differentiation, which is a process of lipid storage, has been used as the main experimental tool for the study of lipid metabolism and obesity (Kim et al., 2018). In cell study, this process is induced by hormonal cocktails including insulin, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), and dexamethasone (DEX). Hormonal exposure induces the expression of transcription regulators which regulate lipid metabolizing genes (Kim et al., 2018). In the early phase of the process, transcription factors, including CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBP) β/δ and Krüppel-Like Factors (KLFs), are induced to affect the expression of adipogenic factors such as C/EBPα and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) in the terminal stage of adipogenesis (Kang et al., 2019). This succession of expression is known to regulate lipid synthetic genes by interacting with their DNA regions (Kim et al., 2018). Adipogenesis involves various signaling pathways that are responsible for the regulation of adipogenic factors. In particular, Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK2-STAT) signaling is known to be an upstream player that controls (early) adipogenesis, and its activation positively regulates the expression of (early) adipogenic factors (Burrell et al., 2020).

Oxidative stress is a cellular pathogenic state in which reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels are out of proportion to endogenous antioxidant responses (Masschelin et al., 2019). It has been linked to pathogenesis of the various diseases including obesity, inflammation, and cancer, in which ROS generation is known to increase (Loboda et al., 2016). Thus, regulation of ROS or oxidative stress could be a solution-oriented approach to manage ROS-mediated diseases. ROS-mediated cellular burden can be reduced by an antioxidant protection system called the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2)/kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1(Keap1) (or NRF2-KEAP1) pathway. This signaling pathway has been involved in metabolic disease conditions, including obesity (Tonelli et al., 2018).

In this study, the effects of GC on lipid accumulation were described in terms of NRF2-connected ROS regulation and early adipogenic control. This study showed that GC-mediated early adipogenic regulation is involved in the JAK2-STAT signaling pathway. This study also demonstrates the potential of GC as a S. chinensis-derived agent to control lipid accumulation or obesity.

Materials and methods

Materials

GC, and antibodies against nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1(KEAP1), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Dallas, TX, U.S.A.). 3-(4,5dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dipenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Amresco, Inc. (Solon, OH, U.S.A.). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and penicillin–streptomycin (PS) were obtained from Hyclone Laboratories Inc. (Logan, UT, USA). Dexamethasone (DEX) and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα), fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), C/EBPβ, Janus kinase 2 (JAK2/pJAK2), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3/pSTAT3), STAT5/pSTAT5, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Denvers, MA, U.S.A.). All chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.

Cell cultures

3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes were cultured and maintained in DMEM containing 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 10% BS, and 1% PS. Adipocyte differentiation was induced at two days after confluency, using DEX (1 μM), IBMX (0.5 mM), and insulin (1.67 μM). After 48 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with insulin and FBS (10%) for two more days. The differentiating culture was maintained and substituted with new DMEM with 10% FBS every two days until cell harvest. Samples were treated every two days from the induction of differentiation with GC (25, 50, and 100 μM), and hydrogen peroxide (50 mM). All samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 0.2%). Cell culture and differentiation of cells were performed at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

MTT assay

Cells (1.5 × 104–1.0 × 105 cells/well) were treated with GC (0–400 μM) every 48 h for 8 days. MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL) solution in serum-free media was replaced and stand for 60 min at 37 °C. The soluble medium was removed, and DMSO was added to solubilize MTT formazan formed on cells. Color intensity was measured at 550 nm (Spectra Max M3; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.).

Oil red O (ORO) staining

Lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes was evaluated using Oil red O (ORO) after 8 d-differentiation. Briefly, 10% formalin was added to cells for 1 h, fixed at 4 °C for 2 h, and washed out with water. Adipocytes were incubated with ORO (0.5%) solution inisopropanol (60%) for 24 h at 25 °C in the dark. The ORO-stained cells were then rinsed, dried, and observed under a microscope, and quantified using ImageJ 1.5 [National Institutes of Health (NIH)].

Determination of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production

Cells were treated with 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (20 μM) for 30 min, and then DMSO was added to disintegrate the cell membrane. ROS-mediated fluorescent DCF level was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader (an excitation: 485 nm, an emission: 535 nm) (SpectraMaxM3; Molecular device, Sunnylvale, CA, USA). In the NBT assay, differentiated cells were washed and incubated with NBT (0.2%) at 25 °C for 90 min. Stained dark-blue formazan was solubilized in acetic acid, and its level was read at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer (Spectra Max M3; Molecular Devices).

Western blot

Protein extracts (50 μg) were obtained from the cell lysates by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 5 min. The protein samples were separated by size using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the gel-containing proteins were moved to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membrane was incubated with 5% non-fat dried milk for 30 min and immunoblotted with the indicated primary antibodies for 24 h (1:1000). The membrane was rinsed three times with PBS. Antibody-bound proteins were secondly incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (1:2000) for 2 h for an enhanced chemiluminescence reaction. The membrane-bound proteins were visualized using LAS imaging software (Fuji, New York, NY, USA), and their intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, National Institutes of Health).

RNA extraction and real time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) based on the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was reversely transcribed from total RNA (1 μg) using a Maxime RT PreMix Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc.). The synthesized cDNA was mixed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and the indicated primers (100 ng/mL) (Table 1). The amplification reaction was performed in triplicate using the AriaMx Real-Time PCR system (Agilent Technologies).

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| KLF4 | CTGAACAGCAGGGACTGTCA | GTGTGGGTGGCTGTTCTTTT |

| KLF5 | ACGTACACCATGCCAAGTCA | GTGGGAGAGTTGGCGAATTA |

| C/EBPδ | AGAAGCTGGTGGAGTTGTCG | CGCAGGTCCCAAAGAAACTA |

| Krox20 | AGTTGGGTCTCCAGGTTGTG | GGAGATCCAGGGGTCTCTTC |

| Catalase | ACATGGTCTGGGACTTCTGG | CAAGTTTTTGATGCCCTGGT |

| SOD1 | GAGACCTGGGCAATGTGACT | GTTTACTGCGCAATCCCAAT |

| Gpx | AGGGTAGAGGC CGGATAAG | AGAAGGCATACACGGTGGAC |

| GAPDH | CTGCGACTTCAACAGCAACT | GAGTTGGGATAGGGCCTCTC |

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) was employed for statistical analysis. Among-group differences were assessed using one-way ANOVA, tukey’s multiple range test, and student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant by different letters. All results are displayed as mean ± standard error (S.E.M.).

Results and discussion

Effect of GC on lipid accumulation and adipogenic factors

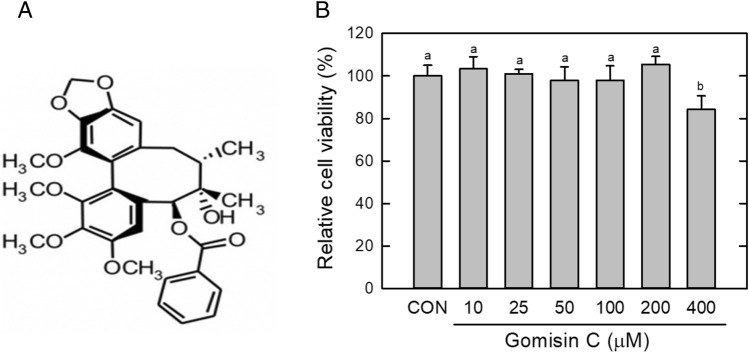

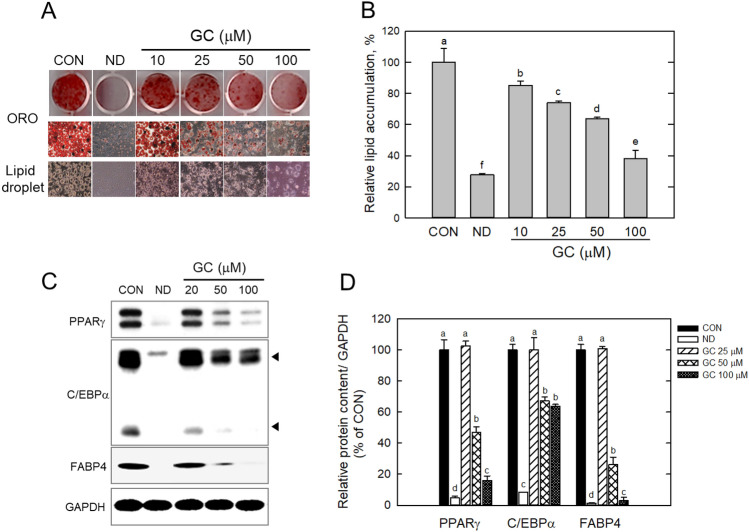

GC did not show any significant (p > 0.05) cell cytotoxicity up to 200 μM concentration; 400 μM of GC showed 83% cell viability compared with the untreated control (CON) (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, 10–100 μM GC was used in subsequent experiments. ORO staining showed that GC effectively inhibited lipid storage in the adipocytes (Fig. 2A). GC dose-dependently suppressed lipid accumulation; 50 μM and 100 μM GC decreased lipid storage by 38% and 61%, respectively, compared with the control (Fig. 2B). GC-mediated lipid reduction results from downregulation of adipogenic factors. Protein expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα was greatly reduced by GC (100 μM) treatment (Fig. 2C); PPARγ was downregulated by approximately 82% compared with the control. FABP4, a target molecule of PPARγ and C/EBPα, was reduced by over 90% (Fig. 2D). These results showed that GC suppressed lipid accumulation by downregulating adipogenic factors. In the terminal adipogenic phase, the increase in factors is accompanied by lipogenesis, in which lipogenic genes, such as fatty acid synthase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and FABP4, are induced (Ahmad et al., 2020). In particular, the increase in FABP4 in circulation has been involved in other metabolic diseases, including insulin resistance, hypertension, and atherosclerosis (Furuhashi, 2019; Saito et al., 2021). A recent study reported that elevated FABP4 in circulation could predict cardiovascular mortality in the population (Saito et al., 2021). In addition to GC, several S. chinensis-derived compounds have shown inhibitory effects on lipid accumulation and obesity (Lee et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021). Gomisin N, another S. chinensis-derived phytochemical, has been known to suppress lipid accumulation and obesity in in vitro and in vivo (Lee et al., ; Lee et al., , 2020, 2021). Lee et al. and Han et al. showed that gomisin N and gomisin A induce a brown fat-like phenotype in adipocytes (Han et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2020). GC is structurally similar to gomisin N and A, but slightly differ owing to an additive phenol group (Fig. S1). S. chinensis-derived phytochemicals have many synonymous names and may be difficult to distinguish. Gomisin C in this study has been also called as schisandrin A, and rarely studied on adipogenic lipid accumulation. Comparing the efficacy of gomsin C and N, gomisin N appears to be more effective in inhibition of lipid accumulation in cell-based studies because the effective concentration of gomisin N has been reported to be lower than that of GC in this study (Dai et al., 2018). However, a direct comparison in the same experiment would prove the difference in efficacy among S. chinensis-derived compounds. In addition, this study shows that GC has potential as another S. chinensis-derived phytochemical to control lipid accumulation.

Fig. 1.

Effect of Gomisin C (A) on cell viability in 3T3-L1 cells. Cell viability was examined by MTT assay in triplicate (B). Results presented in (B) are representative in triplicate

Fig. 2.

Effect of Gomisin C on lipid storage and adipogenic factors in 3T3-L1 cells. Relative lipid contents were assessed and quantified by Oil Red O staining (A) and Image J software (B). Adipogenic factors were determined and quantified by immunoblotting (C) and ImageJ software (D). CON only DMSO treatment, ND not differentiated. Data are representative of triplicates

Effects of GC on early adipogenesis

To understand the inhibitory effect of GC on adopogenic stage GC, the effect of GC on each adipogenic stage was determined (Fig. 3A). GC exhibited an anti-adipogenic effect in early adipogenic stages; treatment with GC from day 0 had a major inhibitory effect. Treatment after day 2 did not mainly contribute to lipid reduction (Fig. 3B, C). Therefore, GC usually inhibit lipid storage by blocking early adipogenesis. This GC-mediated suppression of the early adipogenic stage is supported by the regulation of early adipogenic factors. CCAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ), a pro-early adipogenic factor, was significantly decreased by GC treatment (p < 0.05); 50 μM and 100 μM GC downregulated C/EBPβ protein levels by 17% and 55%, respectively. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), an anti-early adipogenic factor, was upregulated; compared to the control, 50 μM and 100 μM of GC increased the protein abundance of KLF2 by 1.3-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 3D, E). Additionally, KLF4/5, C/EBPδ, and Krox20, which are pro-early adipogenic factors, were downregulated by GC treatment (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that GC blocks early adipogenesis via regulation of early adipogenic factors. Many adipogenic factors are regulated in a stage-by-stage manner to promote adipogenic fat accumulation. In this study, to induce adipocyte differentiation, growth-arrested preadipocytes in confluency were exposed to hormone cocktails, including insulin, IBMX, and DEX. This differentiation process allows cells to re-enter the cell cycle, greatly increasing cell numbers through mitotic clonal expansion (MCE) (Chang and Kim, 2019). During this process, early adipogenic factors are transcriptionally regulated; the expression of C/EBPβ/δ, KLF4/5, and early growth response protein 2 (EGR2 or Krox20) is induced, whereas KLF2 is suppressed in gene expression (Chang and Kim, 2019). Adipogenic regulation of these early factors is known to promote the expression of terminal adipogenic factors (Chang and Kim, 2019) shown in Fig. 2. Several plant-derived compounds have been shown to inhibit lipid accumulation by regulating early adipogenic factors (Choi et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016). In contrast, bisphenol A, an endocrine-disrupting chemical, promotes early adipogenesis process (Chappell et al., 2018). In addition, some phytochemicals that regulate early adipogenesis have been shown to regulate the cell cycle. Choi et al. (2014) showed that anti-early adipogenic effect of indole-3-carbinol, a cruciferous vegetable-derived compound, was involved in the suppression of cyclin A and D protein abundance. Gomisin N was also shown to inhibit early adipogenesis through the suppression of MCE, in which cyclins A and D were downregulated (Chang and Kim, 2019). Based on the anti-adipogenic effect of GC and its structural similarity to gomisin N, GC seems to negatively regulate cell cycle progression. However, further studies are needed to clarify its regulatory effects on the cell cycle.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Gomisin C on early adipogenic steps/factors. Adipocyte differentiation was induced with or without GC for indicated periods (100 μM) (A). Accumulated lipids were stained by ORO and stained levels were evaluated by Image J software (B and C). Cell differentiation was induced for 4 h with or without GC (25 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM). Ealy adipigenic factors were analyzed and quantified by immunoblotting (D), real-time PCR (F), and ImageJ (E, F), respectively. CON: only DMSO treatment, ND: not differentiation. BSM; Bovine serum media (bovine serum + DMEM, not differentiation media). Data are representative of triplicates

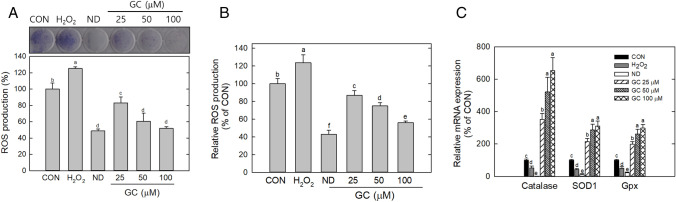

Effect of GC on ROS generation and antioxidant enzyme expression

NBT-derived formazan formation by cells increased with adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 4A). Treatment with hydrogen peroxide, a type of ROS, further increased dark blue formazan. However, GC treatment inhibited formazan production in a dose-dependent manner; and compared with the control, 25 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM GC reduced NBT formazan levels by 18%, 40%, and 48%, respectively. (Fig. 4A). ROS-mediated DCF production from the cells increased with hydrogen peroxide but decreased with GC treatment; GC (100 μM) suppressed DCF levels by 42% (Fig. 4B). These data showed that GC effectively suppressed ROS generation during adipogenesis. In addition, the effect of GC on the antioxidant status was determined. Differentiated cells showed higher mRNA levels of antioxidant enzymes than undifferentiated cells (Fig. 4C). This result indicates that an increase in differentiation-mediated ROS generation may stimulate antioxidant responses. Hydrogen peroxide treatment lowered the mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes, indicating that excessive ROS weakened antioxidant responses. However, GC considerably increased the mRNA level of the antioxidant enzymes; catalase, SOD1, and Gpx by sixfold, threefold, and threefold, respectively, compared with the control (Fig. 4C). This result indicated that GC decreased lipid accumulation by increasing antioxidant response.

Fig. 4.

Effect of Gomisin C on ROS generation and antioxidant enzyme expression. Adipocyte was differentiated for 4 d and was stained by NBT. Dark blue formazan (A) and DCF release from cells were determined by measuring absorbance and fluorescence, respectively (A and B). mRNA levels of catalase, SOD1, and Gpx, were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR, and normalized to GAPDH (C). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 50 μM) wase used as a negative control, respectively. CON only DMSO treatment, ND not differentiation. Data are representative of triplicates

Obesity is a complex disease characterized by enhanced oxidative stress (Kang et al., 2019). Oxidative stress is occurred from the imbalance between ROS generation and antioxidant responses. The increase of ROS such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide is accompanying by adipogenesis (Masschelin et al., 2019). ROS production during differentiation occurs with increased C/EBPβ transactivation and MCE (Kim et al., 2007). Thus, GC-mediated ROS reduction may be involved in the decrease in C/EBPβ protein accumulation and early adipogenesis (Fig. 3). The increase in cellular hydrogen peroxide has been shown to contribute to metabolic complications, such as insulin resistance and obesity (Fazakerley et al., 2018). In addition, peroxiredoxin, a mitochondrial antioxidant that scavenges hydrogen peroxide, is present at low levels in obese individuals and animals (Huh et al., 2012). In contrast, insulin resistance is repressed in elevation of antioxidants, such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase, in diet-induced obese animals (Paglialunga et al., 2015; Tun et al., 2020). A recent study showed that nanoSOD treatment improves triglyceride levels in the liver and plasma (Perriotte-Olson et al., 2016). Choi et al. (2018) showed that plant-derived radical-scavenging materials have anti-adipogenic effects. These results suggests that GC-mediated ROS control leads to anti-adipogenic activity.

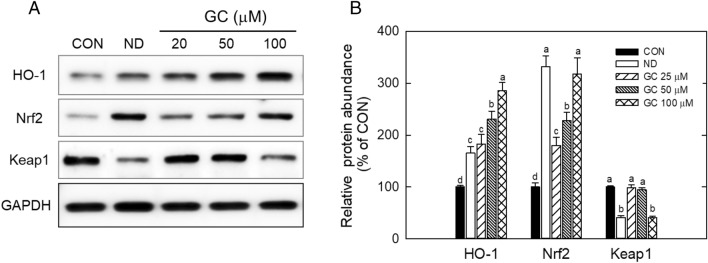

Effect of GC on NRF2/KEAP1 signaling

GC increased NRF2 protein abundance in a dose-dependent manner, in which NRF2 protein levels were enhanced by over threefold, compared to the control, in 100 μM GC (Fig. 5A). Likewise, HO-1, a target protein of NRF2, was upregulated following GC treatment. However, its counterpart, KEAP1, was downregulated; 100 mM GC decreased KEAP1 protein levels by 65%. This result showed that the GC-mediated increase in the antioxidant response was connected to the activation of NRF2-KEAP1 signaling. The NRF2-KEAP1 pathway is an antioxidant and detoxifying system in cells (Loboda et al., 2016). This machinery senses the levels of cellular ROS or electrophiles to protect cells from cellular stress or toxicity (Loboda et al., 2016). The pathogenesis/degeneration of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases is associated with the downregulation of NRF2-KEAP1 signaling while the activation of this signaling has been known to reduce the risk of disease development (Masschelin et al., 2019). In diet-induced obesity, NRF2 activation has been shown to have beneficial effects in preventing fat accumulation and oxidative overload. However, a gene deletion study showed the opposite result; NRF2-knock out condition caused a reduction in body weight and glucose levels (Chartoumpekis et al., 2011). When NRF2-KEAP1 signaling is stimulated by ROS or electrophilic chemicals, the NRF2-KEAP1 complex is disassembled in the cytoplasm. Free NRF2 migrates to the nucleus, thereby promoting the expression of target genes, whereas KEAP1 is disintegrated by the proteasome system (Loboda et al., 2016). Transactivation of NRF2 increases the gene expression of antioxidant or protective enzymes such as heme oxygenase, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1, glutathione S-transferases, and thioredoxin (Tonelli et al., 2018). In the current study, GC suppressed ROS production but upregulated the expression of antioxidant enzymes and NRF2 (Figs. 4, 5), indicating that GC-mediated activation of NRF2-KEAP1 signaling is associated with the reduction of lipid accumulation via regulation of the antioxidant response.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Gomisin C on NRF2/KEAP1 pathway in 3T3-L1 cells. Adipocytes were differentiated with GC or vehicle (DMSO) for 6 days. NRF2 and HO-1 protein abundances were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies (A). The protein levels were quantified by ImageJ software (B). CON only DMSO treatment. ND not differentiation

Effect of GC on JAK/STAT signaling

GC was shown to inhibit JAK-STAT signaling by suppressing its phosphorylation (Fig. 6A). The STAT3 and STAT5 phosphorylation was decreased by 30% and 20%, respectively, in 50 μM and 100 μM GC, respectively (Fig. 6B). JAK2, an upstream mediator of STAT signalling, was significantly inhibited by GC treatment. GC (50 or 100 μM) decreased JAK2 phosphorylation by approximately 60% compared to that in the control. This data indicated that GC inhibited STAT signaling by decreasing JAK2 phosphorylation. Activation of JAK2-STATs signaling is a prerequisite to induce early adipogenesis (Burrell et al., 2020). C/EBPβ, a major early adipogenic factor, is one of STAT3 target genes, in which phosphor-STAT3 binds to its promoter region to induce early adipogenesis (Zhang et al., 2011). In addition, STAT3/5 promotes the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ at the transcriptional level (Kawai et al., 2007; Richard and Stephens, 2014). These studies indicate that STAT signalling regulates both early and terminal adipogenesis. JAK2 is a major kinase that activates STATs by phosphorylating their tyrosine residues (Richard and Stephens, 2014), indicating that JAK2 activation is important for the induction of adipogenesis via STAT signaling. In addition to adipogenic factors, lipid metabolism-related cytokines and hormones are also regulated by JAK2-STAT signaling (Kawai et al., 2007). A recent study reported that lactobacillus-derived cell fractions, called paraprobiotics, inhibit lipid accumulation by regulating JAK2-STAT signaling (Lim et al., 2022). Taken together, the present study indicates that GC suppresses adipogenesis by deactivating JAK2-STAT pathway. As far as our present knowledge goes, this is the first study to demonstrate that the GC-mediated anti-adipogenic effect is exerted by the deactivation of JAK-STAT signaling.

Fig. 6.

Effect of GC on JAK2/STAT pathway in 3T3-L1 cells. Adipocytes were differentiated with GC or vehicle (DMSO) for 2 h. Each protein abundances were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies (A) and the protein levels were quantified by ImageJ software (B). CON only DMSO treatment, ND not differentiation

In conclusion, gomisin C suppresses lipid accumulation by regulating early adipogenesis and ROS levels. GC-mediated reduction of early adipogenesis and ROS production was shown to be due to deactivation of the JAK2-STAT signaling pathway and activation of the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway. This study demonstrated the potential of GC as an edible agent derived from Schisandra chinensis to control lipid accumulation and obesity.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a 2020 research Grant from Sangmyung University.

Abbreviations

- C/EBPα/β/δ

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha/beta/delta

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′-Dichloro-fluorescence diacetate

- DEX

Dexamethasone

- EGR2 (KROX20)

Early growth response protein 2

- FABP4

Fatty acid-binding protein 4

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Gpx

Glutathione peroxidase

- HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1

- IBMX

3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

- KEAP1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- KLF2/4/5

Kruppel-like factor 2/4/5

- NBT

Nitro blue tetrazolium

- NRF2

The nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma

- SOD1

Superoxide dismutase 1

- STAT3/5

Signal transducer and activator of transcription3/5

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ye-Lim You, Email: 0516y@naver.com.

Ji-Yeon Lee, Email: qeadzc1211@naver.com.

Hyeon-Son Choi, Email: hsc1970@smu.ac.kr.

References

- Ahmad B, Serpell CJ, Fong IL, Wong EH. Molecular mechanisms of adipogenesis: The anti-adipogenic role of AMP-activated protein kinase. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 2020;7:76. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell JA, Boudreau A, Stephens JM. Latest advances in STAT signaling and function in adipocytes. Clinical Science. 2020;134:629–639. doi: 10.1042/CS20190522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E, Kim CY. Natural products and obesity: a focus on the regulation of mitotic clonal expansion during adipogenesis. Molecules. 2019;24:1157. doi: 10.3390/molecules24061157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell VA, Janesick A, Blumberg B, Fenton SE. Tetrabromobisphenol-A promotes early adipogenesis and lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Toxicological Sciences. 2018;166:332–344. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartoumpekis DV, Ziros PG, Psyrogiannis AI, Papavassiliou AG, Kyriazopoulou VE, Sykiotis GP, Habeos IG. Nrf2 represses FGF21 during long-term high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:2465–2473. doi: 10.2337/db11-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Liu F, Zheng N, Guo M, Bao L, Zhan Y, Zhang M, Zhao Y, Guo W, Ding G. Wuzhi capsule (Schisandra Sphenanthera extract) attenuates liver steatosis and inflammation during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease development. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2019;110:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HS, Jeon HJ, Lee OH, Lee BY. Indole-3-carbinol, a vegetable phytochemical, inhibits adipogenesis by regulating cell cycle and AMPKα signaling. Biochimie. 2014;104:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SI, Lee JS, Lee S, Lee JH, Yang HS, Yeo J, Kim JY, Lee BY, Kang IJ, Lee OH. Radical scavenging-linked anti-adipogenic activity of Alnus firma extracts. Intrnational Journla of Molecular Medicine. 2018;41:119–128. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun JN, Cho M, So I, Jeon JH. The protective effects of Schisandra chinensis fruit extract and its lignans against cardiovascular disease: a review of the molecular mechanisms. Fitoterapia. 2014;97:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Yin C, Guo G, Zhang Y, Zhao C, Qian J, Wang O, Zhang X, Liang G. Schisandrin B exhibits potent anticancer activity in triple negative breast cancer by inhibiting STAT3. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2018;358:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazakerley DJ, Minard AY, Krycer JR, Thomas KC, Stockli J, Harney DJ, Burchfield JG, Maghzal GJ, Caldwell ST, Hartley RC, Stocker R, Murphy MP, James DE. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes insulin resistance without disrupting oxidative phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2018;293:7315–7328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi M. Fatty acid-binding protein 4 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2019;26:216–232. doi: 10.5551/jat.48710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YH, Kee JY, Hong SH. Gomisin a alleviates obesity by regulating the phenotypic switch between white and brown adipocytes. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2021;49:1929–1948. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X21500919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh JY, Kim Y, Jeong J, Park J, Kim I, Huh KH, Kim YS, Woo HA, Rhee SG, Lee KJ, Ha H. Peroxiredoxin 3 is a key molecule regulating adipocyte oxidative stress, mitochondrial biogenesis, and adipokine expression. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2012;16:229–243. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang MK, Yun YR, Kim JH, Park MH, Jung MH. Gomisin N inhibits adipogenesis and prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity. Scientific Report. 2017;7:40345. doi: 10.1038/srep40345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B, Kim CY, Hwang J, Suh HJ, Choi HS. Brassinin, a phytoalexin in cruciferous vegetables, suppresses obesity-induced inflammatory responses through the Nrf2-HO-1 signaling pathway in an adipocyte-macrophage co-culture system. Phytotherapy Research. 2019;33:1426–1437. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M, Namba N, Mushiake S, Etani Y, Nishimura R, Makishima M, Ozono K. Growth hormone stimulates adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells through activation of the Stat5A/5B-PPARgamma pathway. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2007;38:19–34. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Tang QQ, Li X, Lane MD. Effect of phosphorylation and S-S bond-induced dimerization on DNA binding and transcriptional activation by C/EBPbeta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2007;104:1800–1804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611137104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kang S, Jung Y, Choi HS. Cholecalciferol inhibits lipid accumulation by regulating early adipogenesis in cultured adipocytes and zebrafish. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016;469:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kim CY, Kang B, Hong J, Choi HS. Dibenzoylmethane suppresses lipid accumulation and reactive oxygen species production through regulation of nuclear factor (Erythroid-Derived 2)-like 2 and insulin signaling in adipocytes. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2018;41:680–689. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b17-00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Lee YJ, Kim KJ, Chei S, Jin H, Oh HJ, Lee BY. Gomisin N from schisandra chinensis ameliorates lipid accumulation and induces a brown fat-like phenotype through AMP-activated protein kinase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Interntional Journal of Molecular Science. 2020;21:2153. doi: 10.3390/ijms21062153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Kim JE, Choi YJ, Gong JE, Jin YJ, Lee DW, Choi YW, Hwang DY. Anti-obesity effect of α-cubebenol isolated from schisandra chinensis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1650. doi: 10.3390/biom11111650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JJ, Jung AH, Suh HJ, Choi HS, Kim H. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum K8-based paraprobiotics prevents obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory responses in high fat diet-fed mice. Food Research International. 2022;155:111066. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2016;73:3221–3247. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2223-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masschelin PM, Cox AR, Chernis N, Hartig SM. The impact of oxidative stress on adipose tissue energy balance. Frontiers in Physiology. 2019;10:1638. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglialunga S, Ludzki A, Root-Mccaig J, Holloway GP. In adipose tissue, increased mitochondrial emission of reactive oxygen species is important for short-term high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in mice. Diabetologia. 2015;58:1071–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perriotte-Olson C, Adi N, Manickam DS, Westwood RA, Desouza CV, Natarajan G, Crook A, Kabanov AV, Saraswathi V. Nanoformulated copper/zinc superoxide dismutase reduces adipose inflammation in obesity. Obesity (silver Spring) 2016;24:148–156. doi: 10.1002/oby.21348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard AJ, Stephens JM. The role of JAK-STAT signaling in adipose tissue function. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1842:431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N, Furuhashi M, Koyama M, Higashiura Y, Akasaka H, Tanaka M, Moniwa N, Ohnishi H, Saitoh S, Ura N, Sshimamoto K, Miura T. Elevated circulating FABP4 concentration predicts cardiovascular death in a general population: a 12-year prospective study. Scientific Report. 2021;11:4008. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83494-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szopa A, Ekiert R, Ekiert H. Current knowledge of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. (Chinese magnolia vine) as a medicinal plant species: a review on the bioactive components, pharmacological properties, analytical and biotechnological studies. Phytochemistry Reviews. 16: 195–218 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tonelli C, Chio IIC, Tuveson DA. Transcriptional regulation by nrf2. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2018;29:1727–1745. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun S, Spainhwer CJ, Cottrill CL, Lakhanni HV, Pillai SS, Dilip A, Chaudhry H, Shapiro JI, Sodhi K. Therapeutic efficacy of antioxidants in ameliorating obesity phenotype and associated comorbidities. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2020;11:1234. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Qiu J, Huang Z, Yu Z, Wang W, Hu H, You Y. A comprehensive review of ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. and Schisandra sphenanthera Rehd. et Wils. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 284: 114759 (2022) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang K, Guo W, Yang Y, Wu J. JAK2/STAT3 pathway is involved in the early stage of adipogenesis through regulating C/EBPβ transcription. Journal of Cell Biochemistry. 2011;112:488–497. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.