Highlights

-

•

Retinol fluorescence lifetimes in phosphatidylcholine liposomes consist of a short and long component.

-

•

Changes in the average lifetime resulting from 10% cholesterol or BHT result from changes in the relative amplitude, rather than magnitude, of the two components.

-

•

Excitation of the fluorophore by UV light results in photodegradation of the retinol and lipid peroxidation.

-

•

Cholesterol protects against photodegradation but BHT in some cases can increase it.

Keywords: Retinol, Fluorescence lifetime, FLIM, Photosensitizer, Photodegradation

Abstract

Retinol shows complex photophysical properties that make it potentially useful as an exogenous or endogenous probe of membrane microenvironment, but it has not been fully explored. In this study, we use bulk fluorescence lifetime measurements and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to examine the stability of retinol in phosphatidylcholine (PC) multilamellar and unilamellar vesicles with and without cholesterol. We find that both light and exposure to ambient temperature and oxygen contribute to retinol degradation, with the addition of an antioxidant such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) essential to provide stability, especially in the absence of cholesterol. With exposure to ultraviolet light to excite its native fluorescence, retinol degrades rapidly and can photosensitize vesicles. Degradation can be measured by a decrease in fluorescence lifetime. In POPC vesicles without cholesterol, BHT leads to initially higher lifetimes compared with no BHT, but it increases the rate of photodegradation. The presence of 10 mol % cholesterol protects against this effect, and vesicles with 20 mol % cholesterol show longer lifetimes without BHT under all conditions. Because of its environmental sensitivity, retinol is interesting as a FLIM probe, but careful controls are needed to avoid degradation, and additional work is needed to optimize liposomes for food and cosmetic applications.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Retinol and lipids

Retinol (Vitamin A1) is an essential micronutrient that consists of a cyclic head group, a polyene chain, and an alcohol end group (Fig. 1A). It is practically insoluble in water, but is soluble in ethanol, methanol, and fats and oils. It plays a physiological role in the visual cycle, where it is a precursor to the chromophores necessary for vision. It is also necessary for maintaining integrity and function of all epithelia. Its uses in medicine and commercial products are wide-ranging. Stabilized forms (usually retinyl acetate or palmitate) are used to enrich foods in Vitamin A. Topical retinol and other retinoids are used in pharmaceutical and cosmetic preparations to treat acne and signs of photodamaged skin [1], [2], [3], [4]. Retinoid preparations must be protected from light, refrigerated, and protected with an antioxidant preservative, as exposure to light and oxygen leads to degradation into a variety of potentially harmful compounds, including reactive oxygen species [5], [6], [7]. A substantial amount of research has focused on development of delivery vehicles for retinol, including liposomes, chitosan, pectin, and zein particles [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Cholesterol, which reduces the permeability of a fluid phase bilayer to water and reduces the flexibility of the lipid chains around it (Fig. 1 B) [18], was shown to increase the stability of retinol in liposomes in at least one study [19].

Fig. 1.

Amphipathic structure of retinol and cholesterol. (A) Retinol structure. (B) Schematic of lipids with polar headgroups interacting with cholesterol, leading to locally increased stiffness.

Retinol is photoluminescent, and its emission intensity may be used to determine its concentration to some extent, though varying lipid concentrations can affect emission yield [20,21]. The absorption band at 325 nm with emission at ∼490 nm is due to a π- π transition of the polyene chain. Most literature on retinol is several decades old, and many of the studies use egg or soy phosphatidylcholine (PC) as a solvent. Updated results using modern techniques and purified lipids are therefore of interest. Fluorescence quantum yields and lifetimes have been shown to vary with solvent; reported values of quantum yield are 0.004 in aqueous solvent, 0.011 in ovolecithin (egg PC), and 0.013 in ovolecithin with 30% cholesterol; average lifetimes are 2.5 ns in aqueous buffer, 7 ns in ovolecithin, and 8 ns in ovolecithin plus cholesterol [22]. This variation in lifetime with environment has been reported to result from changes in microviscosity, with retinol reporting largely from the area near the polar headgroups of the lipid bilayer, in contrast to probes such as 1,6-diphenyl- 1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) [23].

1.2. Retinol as a fluorescent probe

Fluorescence lifetimes are sensitive to microenvironments on a spatial scale of the size of the fluorophore, so the use of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) has shown great utility in biology [24]. FLIM may be performed using dyes or fluorescent proteins, or the emission of endogenous fluorophores may be exploited for label-free imaging of living specimens without risk of damage from dyes. The most commonly used endogenous fluorophores are the metabolic cofactors reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), which indicate redox state [25], [26], [27]. Because of its highly environmentally sensitive lifetimes, retinol could potentially be useful as an endogenous or exogenous FLIM probe for lipid microenvironments. However, despite its potentially useful photophysical properties, its use as an endogenous fluorophore for imaging is not often reported. A 2014 study used 2-photon-excitation (TPE) imaging to visualize structures in primate eyes using endogenous fluorophores, including retinol [28]. Progress has been made towards the use of TPE imaging in live human eyes, though the brightest fluorophores are compounds other than retinol [29]. Retinol has also been used for hyperspectral imaging in conjunction with FLIM [30], and identified in a phasor based approach to cell imaging [31].

The goal of this study was to use bulk time-resolved lifetime measurements to characterize fluorescence lifetimes of retinol in liposomes with and without cholesterol, and to compare these results with FLIM of individual vesicles to compare the lifetime patterns seen on the microscopic scale with the bulk measurements. The effects of light exposure were examined in both cases, investigating the ability of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and cholesterol to protect against ultraviolet- and storage-induced degradation.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Chemicals

Crystalline all-trans retinol (Part #R7632), retinol at 100 µg/mL in absolute ethanol stock with 0.1% w/v BHT (reference material, part #V-011), chloroform, methanol, sodium chloride, and cholesterol were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL as a chloroform solution. Crystalline retinol was dissolved to a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL in absolute ethanol, with or without the addition of 0.1% w/v BHT. Cholesterol was dissolved at 20 mg/mL in chloroform. Stocks were stored under nitrogen at -70 ºC in light-proof bottles.

2.2. Liposome preparation

All handling of retinol was performed with the room lights off and the experiment shielded from light by a black curtain.

To produce POPC vesicles, 91.2 µL (3 µmol) POPC and 216 µL retinol stock at 100 µg/mL or 21.6 µL at 1 mg/mL (0.075 µmol) were added to a glass vial, yielding a molar ratio of 40 mol phospholipid:1 mole retinol. If desired, 10 or 20 mol% cholesterol was added at this stage. The vials were rotated under a stream of nitrogen gas to evaporate the solvent, resulting in a thin lipid film on the inner surface of the vials. 1.0 mL of cyclohexane was added to dissolve the thin lipid film in the vial. The samples were vortexed for ∼3 min and frozen for at least 30 min in an n-propyl alcohol and dry ice bath. The frozen samples were lyophilized for at least 1 h to remove the cyclohexane, yielding phospholipids in the form of a dispersed white powder. 3 mL of aqueous buffer (HEPES 10 mM, KCl 60 mM, 30 NaCl 60 mM, pH 7.25) was then added to the vials, which were vortexed thoroughly to produce multilamellar vesicles (MLVs). Some MLVs were reserved for spectroscopy and/or FLIM at this stage; the rest of the preparation was subjected to 9 freeze/thaw cycles to produce large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs), then passed 11 times through a 100 nm pore size filter using an Avanti Mini Extruder at room temperature, which is the manufacturer's recommended practice for obtaining liposomes with a narrow size distribution around the pore size though it does not completely exclude the possibility of multilamellarity [32]. The resulting stock contained 1 mM lipid.

All spectroscopy and imaging studies were performed < 48 h after sample preparation. Samples for fluorescence measurements were prepared at a concentration of 150 μM phospholipid, which is low enough to prevent inner filter effects, by diluting the vesicles into aqueous buffer at a ratio of 180 µL vesicles: 1020 µL buffer into each cuvette. At least 3 independent cuvettes were prepared for each sample or condition.

For measurements of lifetimes in aqueous buffer, retinol in chloroform was dried and resuspended in aqueous buffer by sonication to a concentration of 1 µM as measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy with an extinction coefficient at peak of 52700/mol cm [33]. For measurement of lifetimes in ethanol, ethanol stocks were diluted directly into additional absolute ethanol.

2.3. Fluorescence decay

Bulk time-resolved measurements were performed with a Chronos frequency-domain fluorescence lifetime spectrometer (ISS, Urbana, IL). An external function generator modulated the polarized excitation source at high frequency, producing a sinusoidal wave with a typical frequency range of 5-250 MHz. A reference quantum counter and PMT were employed to adjust for any variations in laser intensity and output. Excitation was at 374 nm and 15 modulation frequencies were used, logarithmically spaced from 5 to 250 MHZ. Temperature was varied and maintained using a water-circulating thermostat. Samples were allowed to equilibrate for at least 10 min after the water bath attained a new set point temperature before the lifetime measurement. A cut-off filter was used in the emission light path to eliminate scattered light. All lifetime measurements were made with the emission polarizer at the magic angle of 54.7° from the vertical polarized excitation beam, and with 1, 4-bis(5-phenyloxazole-2-yl) benzene (POPOP) (=1.35 ns) in absolute ethanol as a lifetime Ref. [34].

2.4. Light exposure

Effects of light exposure were studied by placing the quartz cuvette lengthwise onto a UV transilluminator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for a set period of time. The transilluminator wavelength is 312 nm and power at the sample was measured at 312 nm using a Coherent FieldMaster power meter with an IM2 UV sensor to be ∼900 μW/cm2.

2.5. FLIM

Lifetime images were obtained on a ZEISS LSM 880 confocal system with a Becker & Hickl SPC-150 FLIM module with a BIG2 detector. All images shown were taken using a 63x oil immersion objective (NA = 1.4). To prevent drift during acquisition, vesicles were embedded in low-melting-point agarose (ThermoFisher Scientific) by mixing the vesicle stock 1:1 with liquefied 0.4% agarose in aqueous vesicle buffer. The mixture was pipetted onto a microscope slide and coverslipped before hardening. The wavelengths captured by the BIG2 detector were 500–550 nm (green channel). The red channel (575–610 nm) showed no significant signal. Excitation for FLIM was provided by a Chameleon Ultra Ti:Sapphire laser (Coherent) operating at a rep rate of 80MHz. The two-photon wavelength used for retinol excitation was 730 nm based upon the literature [35]. FLIM data were analyzed using SPCImage (Becker & Hickl). To study the effects of light exposure, the laser power was increased to 7.0 mW (usual acquisition power, 1-2 mW) or a Hg lamp with a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) filter was used to illuminate the sample (excitation 350 ± 25 nm).

2.6. Lifetime analysis

Fluorescence lifetime is the average time a photoexcited molecule spends in the excited state before relaxing to the ground state. This value is determined by the identity of the fluorophore as well as its microenvironment. For a single exponential the time-resolved fluorescence intensity can be expressed as:

| (1a) |

where α is the intensity at t=0 and τ is the lifetime.

For a multiple exponential,

| (1b) |

where are the normalized intensity-weighted factors such that and are the fluorescence intensity decay time constants. The average intensity-weighted fluorescence lifetime is given by

| (2) |

All reported average lifetimes are intensity weighted.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Lifetimes

An example of raw lifetime spectroscopy data is shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1. Retinol in aqueous buffer at 1 µM showed a double-exponential decay, with the faster component consistent with previous results in aqueous solutions; the slower component indicates the formation of micelles, as has also been reported previously [22]. Retinol in ethanol also showed a double-exponential decay, with the average lifetime consistent with previous results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average lifetimes (calculated using Eq. (2)) for retinol in solution and in POPC vesicles with varying temperature. n/d = not done. Errors show standard deviations for 3-4 independent measurements.

| Condition | <τ> 10 ºC (ns) | <τ> 23 ºC (ns) | <τ> 30 ºC (ns) | <τ> 37 ºC (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinol in buffer | n/d | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 |

| Retinol in ethanol | n/d | 2.64 ± 0.05 | n/d | n/d |

| Retinol in ethanol +BHT | n/d | 2.68 ± 0.02 | n/d | n/d |

| Retinol in POPC | n/d | 7.00 ± 0.09 | 6.50 ± 0.03 | 5.95 ± 0.09 |

| Retinol in POPC +BHT (Liquid stock) | 9.8 ± 0.1 | 9.29 ± 0.06 | 8.59 ± 0.07 | 8.26 ± 0.07 |

| Retinol in POPC +BHT (crystalline) | n/d | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 8.29 ± 0.03 | 7.7 ± 0.1 |

| Retinol in POPC + 10% Ch | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 7.31 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 0.1 |

| Retinol in POPC + 10% Ch +BHT | 9.8 ± 0.1 | 8.90 ± 0.08 | 8.42 ± 0.09 | 7.81 ± 0.04 |

| Retinol in POPC + 20% Ch | 11.7 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 0.5 | 9.9 ± 0.4 | 9.6 ± 0.3 |

| Retinol in POPC + 20% Ch +BHT | 11.3 ± 0.3 | 10.6 ± 0.3 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 0.6 |

In POPC LUVs, bulk lifetime measurements usually required three-exponential decays for optimum fitting, although the third (shortest) component was frequently <1% of the total amplitude. Table 1 and Fig. 2A give intensity-weighted average lifetimes and Supplementary Table 1 gives full fits. There was a ∼2 ns decrease in average lifetime as the temperature was raised from 10 ºC to 37 ºC in all samples; the slope of the temperature dependence was nearly identical in all bilayer compositions and experimental conditions. Storage under inert atmosphere with BHT was essential for stability under even the minimal handling required to produce the vesicles. Despite manipulations in the dark, the pre-dissolved liquid ethanol reference material containing BHT showed slightly longer lifetimes than the crystalline stock prepared in our lab; thus, to ensure fair comparisons, all data shown are from the crystalline stock to which BHT was added (or not) after dissolution into ethanol. At 10 ºC, the reference material required only 2 components for an optimum fit (Supplementary Table 1).

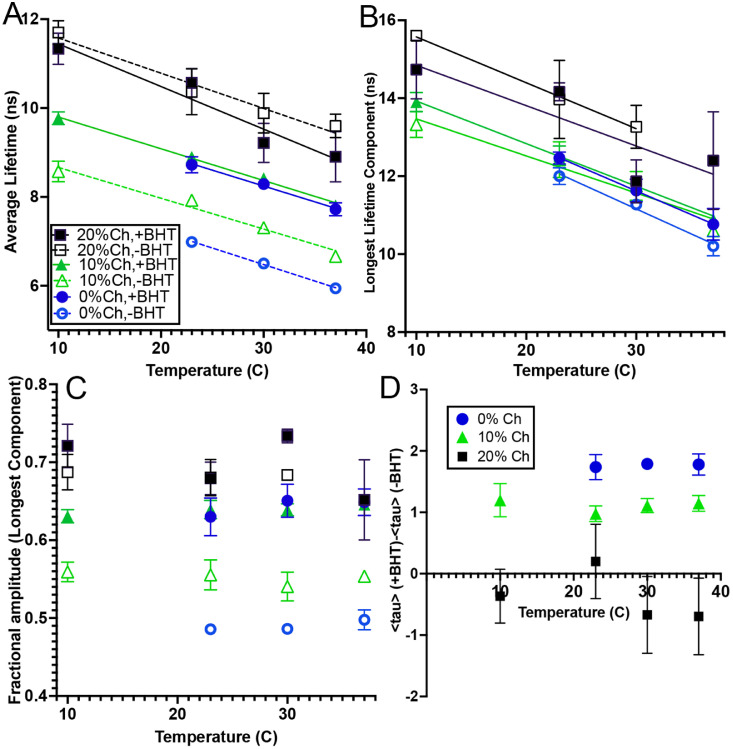

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence lifetimes (also see Table 1) for POPC LUVs with and without 10% Ch and/or BHT. The points are mean values of 3-4 independent preparations with error bars showing standard deviations. The linear fits show slopes and intercepts (R2 > 0.99). (A) Average lifetime <τ> (calculated from Eq. (2)) for retinol in POPC with and without 10 mol% Ch and/or BHT. Straight line fits are: no Ch, no BHT: y = 8.71-.0745x; no Ch, + BHT: y = 10.39 -0.0714x; 10% Ch, no BHT: y = 9.359-.0694x; 10% Ch, + BHT: 10.51-.0715x; 20% Ch, no BHT: 12.37-.0794x; 205 Ch, +BHT: 12.41-.0960x. (B) Values of the longest lifetime component with temperature. There were no statistically significant differences among the samples with 0% or 10% cholesterol; values with 20% cholesterol were higher. Straight line fits are: no Ch, no BHT: y = 15.01-.1282x; no Ch, + BHT: y = 15.27 -0.1214x; 10% Ch, no BHT: y = 14.42-.09515x; 10% Ch, + BHT: 15.02-.1092x; 20% Ch, no BHT: 16.75-.1178x; 20% Ch, +BHT: 15.88-.1035x. (C) Fractional amplitude of the longest component with temperature for the 4 samples. There was no statistically significant change with temperature. (D) Difference in average lifetime between the samples with and without BHT. Lifetimes were significantly longer for the 0% and 10% cholesterol samples, but shorter in the 20% cholesterol sample.

The stock solutions stored at -70 ºC, with or without BHT, were stable over the period of the study (> 4 months) as reflected in consistent lifetimes seen in successive batches of liposomes. Thus, any degradation seen was due to handling after removal from the freezer. Pure POPC liposomes made from stock without BHT showed lifetimes over 1 ns shorter than those with BHT. Liposomes with 10% cholesterol without BHT showed higher lifetimes than pure POPC liposomes, but in the presence of BHT, 10% cholesterol did not affect the lifetime. The presence of 20% cholesterol increased the lifetime with BHT playing an insignificant role (Fig. 2A, Table 1). Examination of the fit parameters showed that the differences in lifetime observed among all the samples (except those containing 20% cholesterol) were almost entirely due to differences in the relative amplitudes of the short (2-3 ns) and long (10–15 ns) lifetime components, rather than changes in the magnitude of these components. There was no statistically significant difference in the magnitude of the longest lifetime component across any of the 0% and 10% cholesterol samples; the longest component was 1-2 ns higher in the 20% cholesterol sample (Fig. 2 B). With BHT, the fraction of the longest component was >60% across all temperatures, with no significant effect of cholesterol. In the absence of BHT, the longest component accounted for ∼55% of the decay in vesicles with 10% Ch, and <50% in vesicles without Ch (Fig. 2C) (also see Supplementary Table 1). The gap in lifetime between vesicles with and without BHT was greater in liposomes without cholesterol than in those with 10% cholesterol; in liposomes with 20% cholesterol, BHT caused a variable but significant reduction in lifetime (Fig. 2D).

The magnitude of the shorter component was more variable than the longer component. In vesicles without cholesterol or BHT, the magnitude of this component and the slope of its change with temperature were not significantly different from the values in pure buffer. The values with 20% cholesterol appeared higher but were highly variable (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

3.2. Light exposure

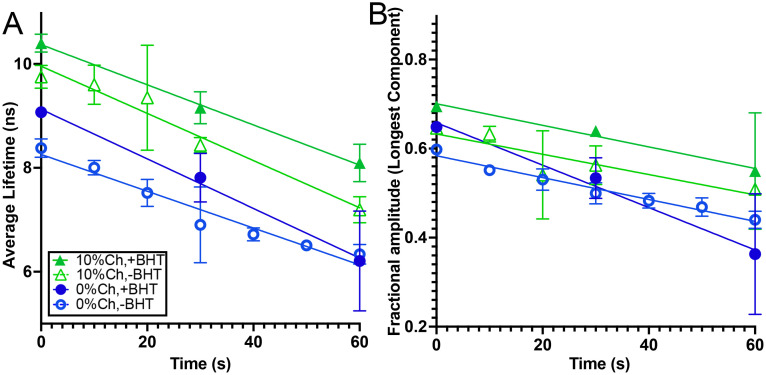

Samples were exposed to UV light until their signal intensity became too weak to measure reliably. The light source used was a 312 nm transilluminator for consistency with our previous results; light fluence may be adjusted by varying the sample distance from the illuminator surface [36]. The slope of the lifetime reduction with exposure time was largely consistent across samples, though somewhat greater with pure POPC with BHT than in any of the other samples (Fig. 3 A). This was largely due to a reduction in the fractional amplitude of the longest component, where the effect was marked (Fig. 3 B). The samples with 20% cholesterol showed extreme variability and no reliable slope could be obtained; the slope of the sample without BHT did not differ significantly from zero (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Lifetime changes with light exposure (at room temperature) to 312 nm transilluminator. The points are mean values of 3-4 independent preparations with error bars showing standard deviations. (A) Average lifetimes with linear fits. Slopes of the fits with standard error are: 0% Ch, no BHT: -.034 ± .006; 0% Ch, +BHT: -.048 ± .008; 10% Ch, no BHT: -.043 ± .003; 10% Ch, +BHT: -.039 ± .004. (B) Fractional amplitude of the longest component with linear fits. Slopes of the fits with standard error are: 0% Ch, no BHT: -.0024 ± .0002; 0% Ch, +BHT: -.005 ± .001; 10% Ch, no BHT: -.0023 ± .0006; 10% Ch, +BHT: -.0024 ± .0009.

We previously [36] used fluorescence intensity measurements with varying light fluence to fit an expression for the fluorescence intensity I as a function of the time of light exposure t (relative to the initial intensity I0) that contains two parameters: one (k1) reflecting first-order photobleaching, and the second-order term (k2) reflecting second-order bleaching or fluorophore reconstitution (depending upon sign):

| (3) |

In our case, the integrated fluorescence intensity is given by Eq. (1b); if only the amplitudes and not lifetimes change with light exposure, then

| (4) |

which is a function of a single changing variable A1(t). Since we have seen that the change in A1(t) is linear in our time range with some slope α:

| (5) |

we can rewrite Eq. (4) as

| (6) |

where the constant B is defined as

| (7) |

For small values of time t, in which is linear, both Eqs. (3) and (6) can be expressed as Taylor expansions to linear order, giving

| (8) |

This relates the slope of the decay of the fractional amplitude of the longest component α, as measured in Fig. 3B, to the product of the first- and second-order rate constants. Although it does not deconvolve the two constants, it does provide useful insight, as Fig. 3B shows that α has a consistent value in all samples except the sample without cholesterol or BHT.

3.3. FLIM

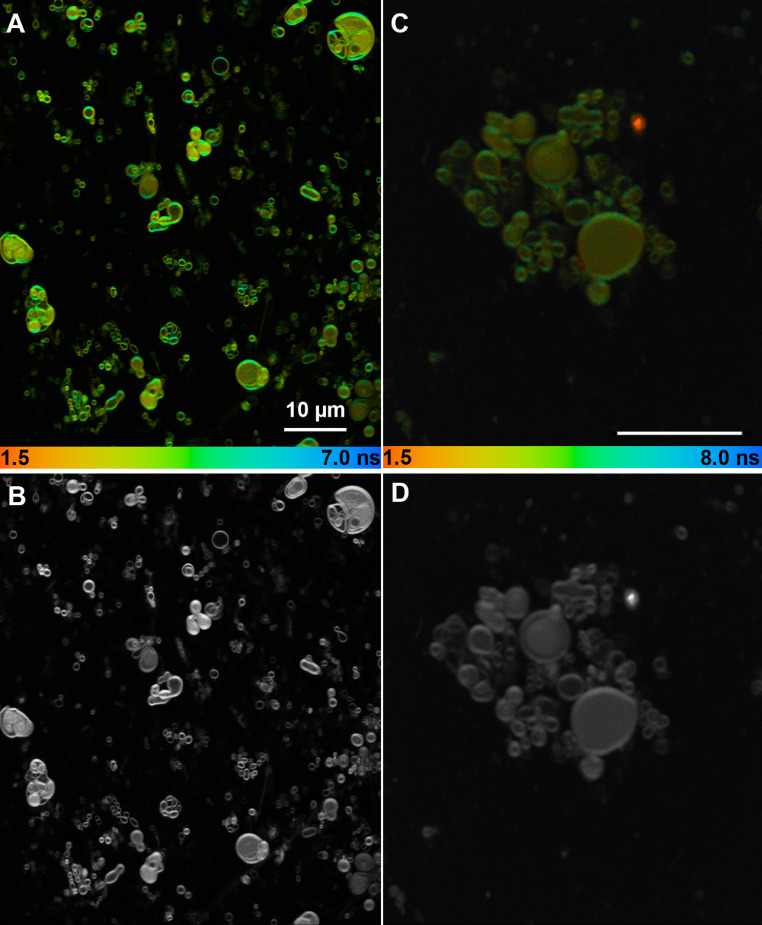

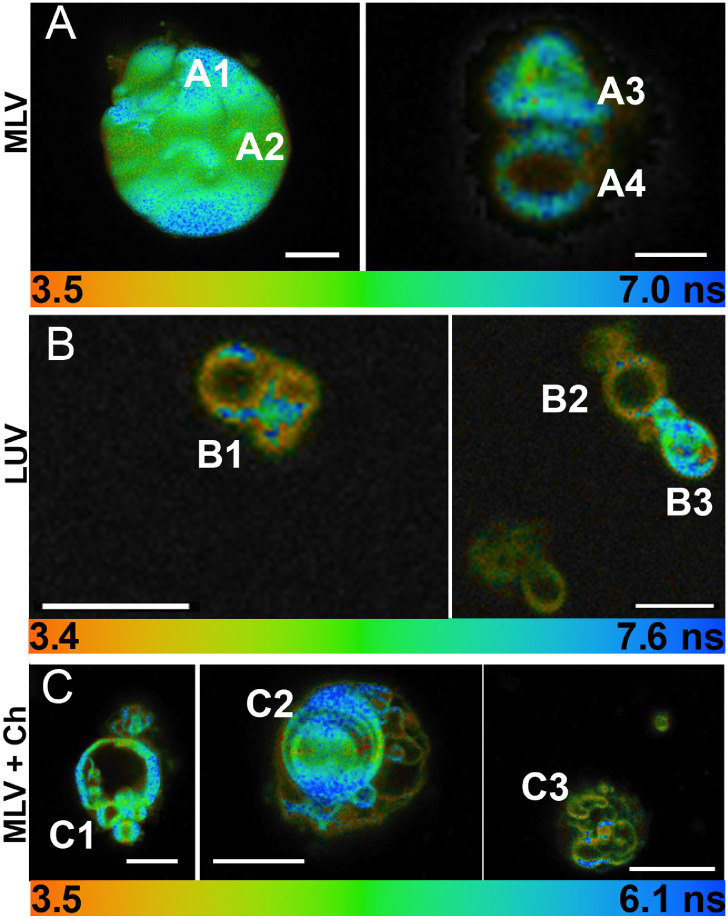

We chose to perform most of the imaging using MLVs, as they were much easier to find and resolve than LUVs. The lifetimes of MLVs and LUVs in bulk solution were nearly the same at 23 ºC (see Supporting Information Fig. S3). The use of agarose as an embedding medium did not change the lifetimes (not shown). Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) of the MLV samples revealed heterogeneous vesicle shape, size, and lamellarity both without cholesterol (Fig. 4 A, B) and with cholesterol (Fig. 4 C, D). As a general rule, longer retinol lifetimes were associated with the outer perimeter of the vesicles, and shorter lifetimes with the vesicle interior, though combinations of both short and long lifetimes were seen in all regions. Close-ups of selected regions of interest (ROIs) are shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 5A shows MLVs without cholesterol or BHT; their measured lifetimes along with the average lifetime of the entire image are given in Table 2. All samples fit to dual-exponential decays; the long component necessitated the use of an incomplete decay model for an accurate fit (see Supporting Information Fig. 4 and Table S2 for comparison between models). Fig. 5B shows LUVs after extrusion. Measured lifetimes were slightly longer in the extruded vesicles, though it is likely that the smallest vesicles were not observed. Fig. 5C shows vesicles with 10% cholesterol (no BHT).

Fig. 4.

FLIM lifetime (A) and intensity (B) of MLVs with retinol, no cholesterol and lifetime (C) and intensity (D) of MLVs with retinol and cholesterol. The color code shows the intensity-weighted average lifetime as indicated.

Fig. 5.

Measured lifetimes from selected ROIs of FLIM images of MLVs and LUVs. Scale bar = 5 µm. Fit parameters given for the indicated regions in Table 2. (A) MLVs. (B) LUVs. (C) MLVs+10% cholesterol. No samples contained BHT.

Table 2.

Lifetimes from FLIM in regions indicated in Fig. 5.

| Sample | <τ> (ns) |

|---|---|

| MLV Region A1 | 7.78 |

| MLV Region A2 | 7.23 |

| MLV Region A3 | 6.96 |

| MLV Region A4 | 6.82 |

| MLV A entire image | 7.21 |

| LUV Region B1 | 8.23 |

| LUV Region B2 | 8.16 |

| LUV region B3 | 8.37 |

| MLV + Ch Region C1 | 6.83 |

| MLV + Ch Region C2 | 7.11 |

| MLV +Ch Region C3 | 6.57 |

| MLV +Ch entire image | 7.15 |

3.4. Effects of light exposure

The 2-photon laser light used to excite the vesicles also led to photobleaching and photodegradation over a time course of several minutes. Fig. 6 shows FLIM images and lifetime histograms of POPC vesicles without cholesterol (Fig. 6A) and with cholesterol (Fig. 6B) before and after exposure to 120s of 2-photon excitation light (no BHT in any samples). In both cases, a drastic shift to shorter lifetimes and distortion of the vesicles was seen. In the lifetime histograms (Fig. 6 C,D) the dominant lifetime peak at ∼6 ns disappeared, and the secondary peak at ∼4 ns increased. In the vesicles without cholesterol, the spectrum became dominated by very fast components with lifetimes < 2 ns (Fig. 6 C). These components were not seen in the cholesterol-containing vesicles. Photobleaching by brief (∼10 s) exposure to Hg lamp excitation through a DAPI filter was also attempted. This led to a complete loss of signal from the POPC-only vesicles (not shown). The cholesterol-containing vesicles retained some signal, but further shifted to ∼2.5 ns (Fig. 6D). Phasor analysis could also be used to examine the distribution of lifetimes before and after light exposure; results were similar to those seen in the histograms (Supporting Information Fig. S5).

Fig. 6.

Selected MLVs before and after exposure to 120 s of 7.0 mW 730 nm laser light. All samples were made from stock with BHT. (A) POPC alone. (B) POPC with 10% Ch. (C) Histograms of lifetimes in the indicated samples without cholesterol. (D) Histograms of lifetimes in the samples with cholesterol. Also shown is a histogram of lifetimes in a sample exposed to excitation through a DAPI filter with a Hg lamp for 30 s.

Time-lapse imaging of illuminated vesicles showed gradual loss of internal vesicle structure followed by distortion and rupture of the vesicle over a time course of 4-5 min (Fig. 7, Supplementary Video 1).

Fig. 7.

Time lapse of a selected region of retinol-containing POPC MLVs illuminated with 730 nm two-photon excitation at 7.0 mW.

4. Discussion

Although retinol is a naturally occurring chromophore and widely used pharmaceutical ingredient, its fluorescence properties have not been widely investigated. Steady-state fluorescence is used to measure vitamin A levels in the food and cosmetics industry [37], [38], [39], and time-resolved measurements are of growing interest in studies of the visual cycle [40,29]. Several reasons for this apparent lack of interest in retinol fluorescence are its low quantum yield and broad blue/green emission that overlaps much cellular autofluorescence. Thus, its fluorescence intensity is of little use in in vivo or tissue measurements. However, fluorescence lifetime measurements can be used to distinguish it from other fluorophores, even in complex environments. A recent study reported FLIM tracing of a retinoid drug, tazarotene, in human skin [41]. Fluorescence lifetime imaging ophthalmoscopy is an emerging area of interest, as well, although the precise nature of the fluorophores involved is not certain [42,43].

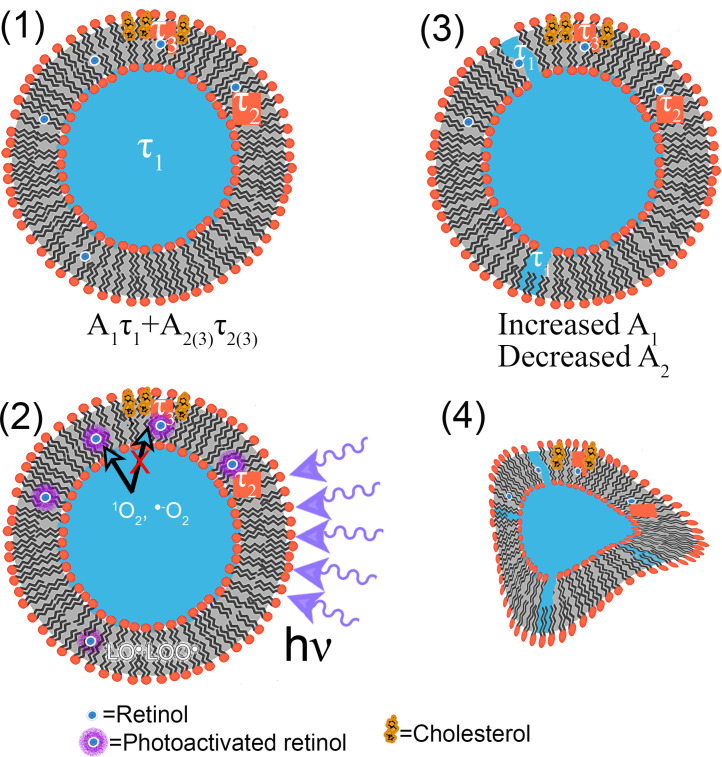

Characterization of retinol fluorescence lifetimes in different environments is necessary to determine its utility as a possible reporter or indicator of environmental conditions. The current study using POPC vesicles reports slightly longer lifetimes than previous reports in the literature, but only when the retinol was preserved with BHT. The variations in lifetime seen with addition of 10% cholesterol and/or BHT resulted from changes in relative amplitudes rather than the lifetimes themselves. With 20% cholesterol, there was an increase in the lifetime of the longest component, and no significant effects of BHT (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Schematic of interaction of retinol, cholesterol, and light with POPC liposomes. (1) Retinol in the aqueous phase has a lifetime τ1. Retinol in lipid has a significantly longer lifetime τ2. In vesicles with 20% cholesterol, this second lifetime has a greater value, τ3. (2) Upon photoexcitation of the retinol, reactive oxygen species 1O2 and ˙−O2 are produced, as well as lipid radicals LO˙ and LOO˙. The presence of cholesterol can inhibit the passage of free radicals through the membrane (indicated by the red X). (3) Lipid radicals and reactive oxygen species can permeabilize the membrane, leading to more exposure of retinol to water so an increased fraction of molecules with lifetime τ1. Areas with cholesterol are less affected. (4) Oxidation and pore formation eventually permeabilize and destroy the vesicle, with many of the retinol molecules degrading into photoproducts that are nonfluorescent or which have lifetimes too fast to measure with our techniques.

The two primary components of the decay were highly consistent across the samples. The shortest component was not significantly different from the lifetime of retinol in aqueous solution (2.5-3 ns), suggesting that decreased lifetimes correlated to increased exposure of the retinol to water. This exposure may occur in intact vesicles, but will increase with oxidative photodamage. Interaction of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by photooxidation of retinol may interact directly with the remaining retinol, but also interact with lipids and cholesterol, leading to peroxy-lipids and oxidized cholesterol products [5,7,44] (Fig. 8B). This effect has been widely studied with photosensitizers in liposomes, where exposure to light may be used to permeabilize the liposome for purposes such as drug delivery [45,46]. Even small amounts of lipid peroxidation can permeabilize vesicles (Fig. 8C). Examination of individual vesicles with FLIM confirmed that exposure to 2-photon laser or mercury lamp excitation led to a decrease in fluorescence intensity and lifetime, with eventual morphological alterations and rupture of the vesicle (Fig. 8D). Thus, it is extremely likely that widespread lipid peroxidation was taking place when the retinol was photoexcited.

These observations are consistent with the protective effects of cholesterol, even at such a low concentration as 10 mol %. A molecular dynamics study has shown that cholesterol can hinder permeation of certain ROS through membranes even without permeabilization, perhaps explaining the increased sensitivity of cholesterol-depleted cancer cells to cold atmospheric plasma treatment [47] (Fig. 8B). As oxidation progresses, cholesterol can prevent pore formation in photosensitized vesicles [48] (Fig. 8C,D). In membranes made with oxidized lipids, cholesterol reduces membrane disorder [49]. In the images in Fig. 6, it can be seen that prolonged 2-photon excitation of vesicles without cholesterol led to vesicle deformation and the creation of many products with lifetimes < 1 ns. In the presence of cholesterol, the vesicles remained intact for significantly longer, and these products did not appear in the time course studied. These breakdown products appear to be associated with the aqueous phase in the images.

In the absence of cholesterol, we found that the antioxidant BHT had a significant effect on the lifetimes of retinol in vesicles. BHT is a lipophilic radical scavenger that is able to intercept lipid radicals (LO• and LOO•) [50]. It can be used to stabilize retinol in vesicles as well as solid lipid nanoparticles [51]. What is surprising is that BHT led to a reduction in lifetime in vesicles containing 20% cholesterol, as well as to faster photodegradation in samples without cholesterol.

These results are all consistent with our previous study using retinol in egg PC MLVs [36]. We found that 18 mol % cholesterol did not protect the retinol from photodegradation, but all samples contained BHT or similar antioxidants. Lifetimes seen in FLIM images were comparable to those reported here. It thus appears that egg PC MLVs are substantially equivalent to POPC LUVs, at least at room temperature.

A third component seen in most of the decays, representing a fraction with lifetime < 1 ns, likely represents decomposition products of various kinds. Oxidative and photodecomposition of retinol is a complex process that leads to different products depending upon the environment; some of these products are fluorescent, but with very low quantum yields and short lifetimes with respect to retinol (<100 ps) [52].

Future work will involve the use of lipids other than POPC, including those of different saturation levels, and the use of reporter dyes such as LAURDAN or dehydroergosterol [53] to further examine vesicle structure. Sterols other than cholesterol may also be of interest.

5. Conclusion

Both bulk and FLIM measurements illustrated the sensitivity of retinol to UV light. BHT helps protect vesicles in the absence of cholesterol, but has no effect at 10% cholesterol and an apparently deleterious effect at 20% cholesterol. Retinol may be useful as a FLIM probe indicating oxidation state and/or vesicle permeability.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

L. Sumrall: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. L. Smith: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. E. Alhatmi: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Y. Chmykh: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. D. Mitchell: Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. J. Nadeau: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a contract from Marie-Veronique Inc. to Portland State University. We acknowledge expert technical assistance by staff in the Advanced Light Microscopy Core in the Department of Neurology and Jungers Center at Oregon Health and Science University.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbadva.2023.100088.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kafi R., et al. Improvement of naturally aged skin with vitamin A (retinol) Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:606–612. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.5.606. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17515510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varani J., et al. Vitamin A antagonizes decreased cell growth and elevated collagen-degrading matrix metalloproteinases and stimulates collagen accumulation in naturally aged human skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2000;114:480–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00902.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10692106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farris P., Zeichner J., Berson D. Efficacy and tolerability of a skin brightening/anti-aging cosmeceutical containing retinol 0.5%, niacinamide, hexylresorcinol, and resveratrol. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD. 2016;15:863–868. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27391637 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho E.T., et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled comparative trial of the anti-aging properties of non-prescription tri-retinol 1.1% vs. prescription tretinoin 0.025% J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD. 2012;11:64–69. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22206079 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolleson W.H., et al. Photodecomposition and phototoxicity of natural retinoids. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2005;2:147–155. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2005010147. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16705812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu P.P., et al. Photoreaction, phototoxicity, and photocarcinogenicity of retinoids. J. Environ. Sci. Health C. 2003;21:165–197. doi: 10.1081/GNC-120026235. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15845224 Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu P.P., et al. Photodecomposition of vitamin A and photobiological implications for the skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007;83:409–424. doi: 10.1562/2006-10-23-IR-1065. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17576350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argimoon M., et al. Development and characterization of vitamin a-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for topical application. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2017;28:1177–1184. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000404521000005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Y., Pyo S.M., Muller R.H. smartLipids (R) as third solid lipid nanoparticle generation - stabilization of retinol for dermal application. Pharmazie. 2017;72:728–735. doi: 10.1691/ph.2017.7016. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000426406700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eskandar N.G., Simovic S., Prestidge C.A. Chemical stability and phase distribution of all-trans-retinol in nanoparticle-coated emulsions. Int. J. Pharm. 2009;376:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.04.036. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000267790800024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang S.J., Sun S.L., Chiu C.C., Wang L.F. Retinol-encapsulated water-soluble succinated chitosan nanoparticles for antioxidant applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2013;24:315–329. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2012.690278. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000316011600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S.C., et al. Stabilization of retinol through incorporation into Liposomes. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;35:358–363. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000177173900002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ro J., et al. Pectin micro- and nano-capsules of retinyl palmitate as cosmeceutical carriers for stabilized skin transport. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015;19:59–64. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2015.19.1.59. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000347747200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan Y., Tikekar R.V., Wang M.S., Avena-Bustillos R.J., Nitin N. Effect of barrier properties of zein colloidal particles and oil-in-water emulsions on oxidative stability of encapsulated bioactive compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;43:82–90. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000345683500011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emami S., Azadmard-Damirchi S., Peighambardoust S.H., Valizadeh H., Hesari J. Liposomes as carrier vehicles for functional compounds in food sector. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2016;11:737–759. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000375599800006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shukla S., et al. Current demands for food-approved liposome nanoparticles in food and safety sector. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02398. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000417046800002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goncalves A., Estevinho B.N., Rocha F. Microencapsulation of vitamin A: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016;51:76–87. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000375336300009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakraborty S., et al. How cholesterol stiffens unsaturated lipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:21896–21905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004807117. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32843347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S.C., Lee K.E., Kim J.J., Lim S.H. The effect of cholesterol in the liposome bilayer on the stabilization of incorporated retinol. J. Liposome Res. 2005;15:157–166. doi: 10.1080/08982100500364131. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000234273200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drujan B.D., Castillon R., Guerrero E. Application of fluorometry in determination of vitamin A. Anal. Biochem. 1968;23:44–52. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90007-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5645128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furr H.C. Analysis of retinoids and carotenoids: problems resolved and unsolved. J. Nutr. 2004;134:281S–285S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.281S. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14704334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radda G.K., Smith D.S. Retinol: a fluorescent probe for membrane lipids. FEBS Lett. 1970;9:287–289. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80379-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11947694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schachter D., Shinitzky M. Fluorescence polarization studies of rat intestinal microvillus membranes. J. Clin. Investig. 1977;59:536–548. doi: 10.1172/JCI108669. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berezin M.Y., Achilefu S. Fluorescence lifetime measurements and biological imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2641–2684. doi: 10.1021/cr900343z. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20356094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skala M.C., et al. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19494–19499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708425104. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18042710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blacker T.S., et al. Separating NADH and NADPH fluorescence in live cells and tissues using FLIM. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3936. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4936. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24874098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Datta R., Heaster T.M., Sharick J.T., Gillette A.A., Skala M.C. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy: fundamentals and advances in instrumentation, analysis, and applications. J. Biomed. Opt. 2020;25:1–43. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.25.7.071203. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32406215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palczewska G., Golczak M., Williams D.R., Hunter J.J., Palczewski K. Endogenous fluorophores enable two-photon imaging of the primate eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:4438–4447. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14395. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24970255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palczewska G., et al. Noninvasive two-photon optical biopsy of retinal fluorophores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117:22532–22543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007527117. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32848058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue Y., et al. Retinal organoids long-term functional characterization using two-photon fluorescence lifetime and hyperspectral microscopy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.796903. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34955757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stringari C., et al. Phasor approach to fluorescence lifetime microscopy distinguishes different metabolic states of germ cells in a live tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:13582–13587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108161108. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21808026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott H.L., et al. On the mechanism of bilayer separation by extrusion, or why your luvs are not really unilamellar. Biophys. J. 2019;117:1381–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.09.006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31586522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaffer M.W., et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of retinol, retinyl esters, tocopherols and selected carotenoids out of various internal organs form different species by HPLC. Anal. Methods. 2010;2:1320–1332. doi: 10.1039/c0ay00288g. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20976035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelezetsky I., Tossi A. Alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides–using a sequence template to guide structure-activity relationship studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1436–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16678118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imanishi, Y. & Palczewski, K. in Retinoids: methods and protocols, Vol. 652 247-261 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Chmykh Y.G., Nadeau J.L. Characterization of retinol stabilized in phosphatidylcholine vesicles with and without antioxidants. ACS Omega. 2020;5:18367–18375. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c02102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32743212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.San Andres M.P., Vera S., Torre M., Valiente M. Retinol fluorescence in lecithin/n-butanol/water aggregates: a new improvement for its analysis in cosmetics without pretreatment. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;399:851–859. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4322-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21049268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vinas P., Bravo-Bravo M., Lopez-Garcia I., Hernandez-Cordoba M. Quantification of beta-carotene, retinol, retinyl acetate and retinyl palmitate in enriched fruit juices using dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled to liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection and atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1275:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.12.022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23290361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura Y., Inoue H., Takemoto S., Hirano K., Miyaura K. A rapid method to measure serum retinol concentrations in japanese black cattle using multidimensional fluorescence. J. Fluoresc. 2021;31:91–96. doi: 10.1007/s10895-020-02640-w. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33094367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palczewska G., et al. Noninvasive multiphoton fluorescence microscopy resolves retinol and retinal condensation products in mouse eyes. Nat. Med. 2010;16:1444–1449. doi: 10.1038/nm.2260. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21076393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong S., et al. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy with phasor analysis for visualizing multicomponent topical drug distribution within human skin. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:5360. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62406-z. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32210332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sauer L., Vitale A.S., Modersitzki N.K., Bernstein P.S. Fluorescence lifetime imaging ophthalmoscopy: autofluorescence imaging and beyond. Eye. 2021;35:93–109. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01287-y. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268846 (Lond) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernstein, P. et al. in High resolution imaging in microscopy and ophthalmology: new frontiers in biomedical optics 10.1007/978-3-030-16638-0_10. (ed. J.F. Bille) 213-235 (Cham (CH); 2019). [PubMed]

- 44.Cherng S.H., et al. Photodecomposition of retinyl palmitate in ethanol by UVA light-formation of photodecomposition products, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129–138. doi: 10.1021/tx049807l. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000227168000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Derycke A.S., de Witte P.A. Liposomes for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.07.014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14706443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massiot J., et al. Impact of lipid composition and photosensitizer hydrophobicity on the efficiency of light-triggered liposomal release. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:11460–11473. doi: 10.1039/c7cp00983f. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28425533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van der Paal J., Verheyen C., Neyts E.C., Bogaerts A. Hampering effect of cholesterol on the permeation of reactive oxygen species through phospholipids bilayer: possible explanation for plasma cancer selectivity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:39526. doi: 10.1038/srep39526. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28059085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van der Paal J., Neyts E.C., Verlackt C.C.W., Bogaerts A. Effect of lipid peroxidation on membrane permeability of cancer and normal cells subjected to oxidative stress. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:489–498. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02311d. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28791102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schumann-Gillett A., O'Mara M.L. The effects of oxidised phospholipids and cholesterol on the biophysical properties of POPC bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2019;1861:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.07.012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30053406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yehye W.A., et al. Understanding the chemistry behind the antioxidant activities of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT): a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;101:295–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.06.026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26150290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jee J.P., Lim S.J., Park J.S., Kim C.K. Stabilization of all-trans retinol by loading lipophilic antioxidants in solid lipid nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2006;63:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.12.007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16527470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samimi K., et al. In situ autofluorescence lifetime assay of a photoreceptor stimulus response in mouse retina and human retinal organoids. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2022;13:3476–3492. doi: 10.1364/BOE.455783. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35781966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chong P.L., Olsher M. Fluorometric assay for detection of sterol oxidation in liposomal membranes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;400:145–158. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-519-0_10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17951732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.