Abstract

The reactivities of halido[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (chlorido (5), bromido (6), iodido (7)), bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (8), and bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]dihalidogold(III) (chlorido (9), bromido (10), iodido (11)) complexes against ingredients of the cell culture medium were analyzed by HPLC. The degradation in the RPMI 1640 medium was studied, too. Complex 6 quantitatively reacted with chloride to 5, while 7 showed additionally ligand scrambling to 8. Interactions with non-thiol containing amino acids could not be detected. However, glutathione (GSH) reacted immediately with 5 and 6 yielding the (NHC)gold(I)-GSH complex 12. The most active complex 8 was stable under in vitro conditions and strongly participated on the biological effects of 7. The gold(III) species 9–11 were completely reduced by GSH to 8 and are prodrugs. All complexes were tested for inhibitory effects in Cisplatin-resistant cells, as well as against cancer stem cell-enriched cell lines and showed excellent activity. Such compounds are of utmost interest for the therapy of drug-resistant tumors.

Introduction

The need for new and improved drugs in tumor therapy is growing rapidly, because of the occurrence of an increased number of tumoral diseases that are resistant to conventional anticancer drugs. Especially, metallodrugs are promising candidates to circumvent acquired and intrinsic resistance.1−6 In particular, gold complexes were established as effective cytostatics, since the approval of Auranofin in 1985 as a drug against rheumatoid arthritis.7−11 Auranofin is now approved by the FDA for phase-II clinical trials in cancer therapy.12

During the past years, gold containing drug candidates with N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) as ligands received high attention, because of their easy synthesis and good biological activity.8,13−16 Antiproliferative effects of (NHC)gold(I)-X complexes where X represents a leaving group are well documented. This particularly applies to halido derivatives. While the meaning of halido leaving groups at platinum(II) complexes on the reactivity in water and thus also on the cytotoxicity has been intensively studied,17,18 comparable investigations with (NHC)gold(I)-X (X = Cl, Br, I) complexes are rather rare. In aqueous solution, nucleophiles can force ligand exchange reactions, but ligand scrambling is observed, too.19 Chloride, present in cell culture media, transforms the bromido complex to the chlorido species as demonstrated in time-dependent experiments on the example of halido[3-ethyl-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-(2-methoxypyridin-5-yl)-1-propyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) complexes (mono-NHC-Au(I)-X, Chart 1). Kinetic reactions with other nucleophiles of the media, e.g., amino acids or glutathione (GSH), were not investigated yet, although such reaction is described for other metal complexes, including Cisplatin.20−22 However, even for Cisplatin, this issue has not yet been fully elucidated as recently discussed by Hall.23

Chart 1. Reaction Behavior of Halido[3-ethyl-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-(2-methoxypyridin-5-yl)-1-propyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) Complexes (mono-NHC-Au(I)-X, X = Cl, Br, I).

Unlike platinum(II) complexes, aquation is not the preferred reaction of mono-NHC-Au(I)-X complexes in water. Instead, they show partially ligand scrambling resulting in the cationic [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex (bis-NHC-Au(I), Chart 1) and [Au(I)X2]− ion. The latter finally decomposes to Au(0).24,25

Especially, the mono-NHC-Au(I)-I complex displayed this reaction during the first minutes of incubation.

Such transformations are of high importance for the interpretation of the biological results, because there are several clues that the antiproliferative activity of [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ species is generally more than 5-fold higher than that of the related (NHC)gold(I)-X (X = Cl, Br, I) complexes.26−31

In water-free organic solvent, e.g., dimethylformamide (DMF), the mono-NHC-Au(I)-X complexes (Chart 1) were stable for 72 h (degradation <2%),24 so stock solutions for the in vitro testing can be prepared. The final concentrations for the cell culture experiments were achieved by dilution with the respective medium, to realize a maximum amount of organic solvent of 0.1%.

It is assumed that the first contact with the medium started the ligand scrambling of mono-NHC-Au(I)-X and present nucleophiles force the degradation further. Therefore, we investigated in a preliminary study the stability of the complexes in acetonitrile/water = 50/50 (v/v) in the presence of 0.9% NaCl. To simulate the reaction with medium ingredients, the complexes were treated with a 20-fold excess of iodide as a model nucleophile.

Mono-NHC-Au(I)-Br and mono-NHC-Au(I)-I rapidly reacted in NaCl solution to mono-NHC-Au(I)-Cl, but also underwent a distinct degradation to bis-NHC-Au(I) (Chart 1).19,27,32

Iodide as the nucleophile led to a fast reaction to mono-NHC-Au(I)-I and subsequently to an increased formation of bis-NHC-Au(I).

These interesting results induced us to monitor the transformation of (NHC)gold(I) complexes in the cell culture medium more detailed on the example of halido[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (chlorido (5), bromido (6), iodido (7)), bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (8), and bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]dihalidogold(III) (chlorido (9), bromido (10), iodido (11)) complexes.

It is very likely that reaction products reduce on the one hand the concentration of the investigated complex and on the other hand have antiproliferative activity themselves.

The RPMI 1640 cell culture medium used in this study contains, besides numerous l-amino acids, vitamins such as biotin, i-inositol, or vitamin B12. Also present is a large amount of glucose and chloride containing inorganic salts (sodium and potassium chloride) as well as the tripeptide GSH.

In this study, we reacted the halido(NHC)gold(I) complexes 5–7 with main ingredients of the medium, e.g., chloride and amino acids. The products, in particular, the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ species, were time-dependent quantified by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis.

Besides the reaction with each nucleophile, the degradation of the complexes in a complete RPMI 1640 cell culture medium was monitored.

Another relevant aspect is the presence of GSH in the cell culture medium. The glutathione ″supersystem″ causes detoxification due to binding of GSH to heavy metals and other toxins.33−35 Since it is well known that gold complexes have a high affinity for thiol-bearing compounds,36 we also quantified the reaction of the (NHC)gold complexes 5–7 with GSH.

Of further interest is the redox behavior of GSH, which allows a reduction of Au(III) to Au(I). Therefore, we included in this study [(NHC)2Au(III)X2]+ complexes with X = Cl (9), Br (10), and I (11) and determined their stability in the presence of GSH.

Furthermore, the complexes 5–11 were investigated for antiproliferative effects in various cell lines, sensitive and resistant to known cytostatics, as well as in cancer cell lines with enriched proportions of cells with stem cell characteristics (cancer stem cells, CSC).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Characterization

The synthesis of the complexes 5–11 was performed in a multistep procedure as depicted in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Routes to Obtain Complexes 5–11.

The reaction of benzil (1) with paraformaldehyde (PFA) and ammonium acetate in concentrated acetic acid yielded the 4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazole 2,37 which was subsequently N,N′-diethylated with iodoethane and sodium hydride (→3) in anhydrous acetonitrile (ACN).32,38

Since iodide is a strong coordinative anion, which forces the formation of iodido(NHC)gold(I) complexes as a by-product in the synthesis of the chlorido/bromido(NHC)gold(I) derivatives,19 an anion exchange with 3 was carried out using potassium hexafluorophosphate in methanol (MeOH)/water (→4).

The chlorido(NHC)gold(I) complex 5 and bromido(NHC)gold(I) complex 6 were synthesized from the 1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazolium hexafluorophosphate salt (4) with silver oxide, chlorido(dimethyl)sulfidegold(I), and a 5-fold excess of lithium chloride or lithium bromide, respectively, following the procedure as previously described.19,27,38,39 The complexes were purified by silica column chromatography with dichloromethane (DCM) and MeOH.40

A simple Cl/I exchange reaction of 5 with sodium iodide in dry acetone for only 5–10 min at room temperature (rt) provided the iodido(NHC)gold(I) complex 7 in high purity.19

In a similar way, the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 was prepared from the bromido(NHC)gold(I) complex 6 by reaction with an equimolar amount of 4 for several days.11,26,27 To separate 8 from unreacted educts, purification by column chromatography was necessary.11,27

Oxidation of 8 with either dichloroiodobenzene (PhICl2), bromine, or iodine yielded the (NHC)gold(III) derivatives 9–11, respectively.26,41 All compounds could be obtained in high purity as determined by HPLC (>97%, Figures S1–S7). For structural characterization, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) were used.

The influence of the halido ligands on the NHC resonances in the 1H NMR spectra of 5–11 (Figures S8–S14) was only marginal and did not allow a structural discrimination. However, this is possible based on the resonances of the C2 carbon directly bound to gold(I/III). From the 13C NMR spectra (Figures S15–S21), it is obvious that the chemical shift depends on the bound halide and oxidation state of the metal center.

As expected, a low-field shift dependent on the electronic density was observed in the (NHC)Au(I)-X series (5 (X = Cl: 169.21 ppm) < 6 (X = Br: 172.83 ppm) < 7 (X = I: 179.96 ppm)).31,40,42

This resonance was located in case of the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 at 182.63 ppm. Oxidation to [(NHC)2Au(I)X2]+ caused a strong high-field shift: 11 (X = I: 142.84 ppm) < 10 (X = Br: 149.99 ppm) < 9 (X = Cl: 153.26 ppm).

X-Ray crystallography confirmed the structure of the complexes 5–11 (Figure 1 and Figures S22–S25). Crystals were grown by slow crystallization over several days from an ACN solution (for crystallographic data, see Tables S1–S8).

Figure 1.

ORTEP of 5, 8, and 9. For 6, 7, 10, and 11 see the Supporting Information.

The spatial structures of the NHC ligand and the length of the NHC-gold bond (1.995–2.028 Å) were nearly identical in all (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes, while the Au(I)-X distance (2.299 Å (5), 2.394 Å (6), and 2.584 Å (7)) increased with the atomic radius of the halide. The complexes formed slightly distorted columnar structures with Au(I)-Au(I) distances of 3.532 and 3.579 Å in 5 and 6, as well as of 4.011 Å in 7. These values point to weak aurophilic interactions.

The [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 (Au(I)-Au(I) distance: 9.680 Å) and [(NHC)2Au(III)X2]+ complexes 9–11 (Au(I)-Au(I) distances: 8.992 Å (9), 11.898 Å (10), and 7.921 Å (11)) showed no Au(I)-Au(I) interactions in the crystal.

The ligands took an orientation, in which the NHC moieties are perpendicularly arranged.

Oxidation to Au(III) and coordination of two halido ligands resulted in a square planar environment at the metal center. The NHCs were aligned perpendicular to this plane due to the steric repulsion with the halido ligands.

Reactivity Studies

In a previous study, we established an HPLC system, which allows the quantification of mono-NHC-Au(I)-X (X = Cl, Br, and I) in the presence of nucleophiles. This method was adapted to the analysis of the complexes 5–11.

As mentioned above, the RPMI 1640 medium contains as nucleophiles besides chloride a variety of amino acids and GSH, which can coordinate to the metal or be involved in the redox reaction with gold(I/III).

All nucleophiles (chloride, amino acids, and GSH) were separately reacted with 5–11 in ACN/water = 50/50 (v/v) mixtures at a complex concentration 0.5 mM. This solvent composition was chosen to prevent precipitation of the complex and the formed degradation products.

As a source for chloride, a NaCl (12.0 g/L)/KCl (0.8 g/L) solution was prepared. After mixing with ACN (50/50 (v/v)), the concentration corresponds to that in the medium.

Amino acids, as well as GSH, were used in 20-fold excess, as realized at a complex concentration of 10 μM in the cell culture medium. Thereto, the respective complex, dissolved in ACN (1 mM), was combined with the same amount of aqueous solution of the nucleophile (20 mM).

The mixture was then incubated for 24 h at rt and monitored at various time points via HPLC using an RP-C18 column and gradient elution (70/30 (v/v) to 90/10 (v/v)) of ACN/water (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)).

It must be mentioned that ACN can act as a weak nucleophile and is able to displace the halide from the gold(I) center of (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes, resulting in the ((NHC)Au(I)-ACN) species. This reaction product would be the same for 5–7.

However, the chromatograms of the complexes in ACN solution (Figures S1–S3) show peaks with different retention times (5: tR = 5.13 min, 6: tR = 5.92 min, and 7: tR = 7.00 min). An additional peak probably caused by (NHC)Au(I)-ACN is not present. Transformation to the Au(I)-ACN can therefore be excluded.

A further clue that the peak at tR = 5.13 min in the chromatograms of 5 results from (NHC)Au(I)-Cl and not from (NHC)Au(I)-ACN can be driven from Figure 2. High chloride concentrations prevent the substitution of the chloride leaving group by weak nucleophiles. As depicted in Figure 2, only a small amount (0.9%) of 5 underwent ligand scrambling to the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 during 24 h of incubation. No further peak of a possible (NHC)Au(I)-ACN species was observed.

Figure 2.

HPLC chromatograms of 5–11 (solution: ACN/water = 50/50 (v/v)) in the presence of 6.0 g/L NaCl and 0.4 g/L KCl at t0h (A) and t24h (B). Complex concentration: 0.5 mM.

In contrast, the bromido derivative 6 reacted quantitatively to 5 immediately after mixture of complex and chloride solution (Figure 2A), followed by the same degradation profile as observed for 5 (Figure 2B).

A slightly different reaction behavior showed 7. At t0h (exactly after 1.5 min), 13.3% of 7 converted to 5 and 3.6% to 8 (Figure 2A). After 24 h, 18.9% of 8 was detected. The quantity of 5 stayed constant (Figure 2B).

Incubation of 8 under the same conditions did not result in any degradation. This finding proves that it is the most stable complex and that its formation from (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes 5–7 is irreversible.

In the next step, the stability of the gold(III) species 9–11 in the presence of chloride was investigated (Figure 2).

Ligand exchange at the dichlorido complex 9 was not observed. However, it was slightly reduced to 8 during 24 h of incubation (by 12.5%).

In contrast, the dibromido derivative 10 underwent preferred substitution reaction to 9 (t0h: 24.0%, t24h: 54.4%). The amount of 8 remained nearly constant (t0h: 2.2%, t24h: 5.1%) during 24 h.

The iodido ligands at the gold(III) center of 11 stabilized the complex. In chloride containing solution, only traces of 9 (0.4%) were detected at t0h without further degradation.

Next, it was evaluated on the example of 7, whether (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes generally interact with amino acids available in the medium.

The HPLC analysis indicated that 7 did not react with the amino acids. Only ligand scrambling to 8 occurred. Time-dependent investigations pointed out that this reaction mostly finished within the first 30 min of incubation (Figure 3). Only in pure ACN/water and in the presence of glutamic acid (Glu) or methionine (Met), a further degradation to 8 took place (t24h: Glu (31.6%), Met (27.5%), and water (31.2%)).

Figure 3.

Formation of [(NHC)2Au(I)]+8 from 7 in the presence of 20 equiv of non-thiol containing amino acid in ACN/water = 50/50 (v/v). Complex concentration: 0.5 mM.

Interestingly, arginine (Arg) diminished the formation of 8. After 30 min, the ratio of 7/8 was 90/10 and remained stable until 24 h of incubation (Figure 3 and Figure S26).

The most important bionucleophile in the medium represents GSH, which is a strong nucleophile and strong reductant due to its cysteine moiety. It was incubated together with the respective complex (5–11), and the results are depicted in Figure 4.

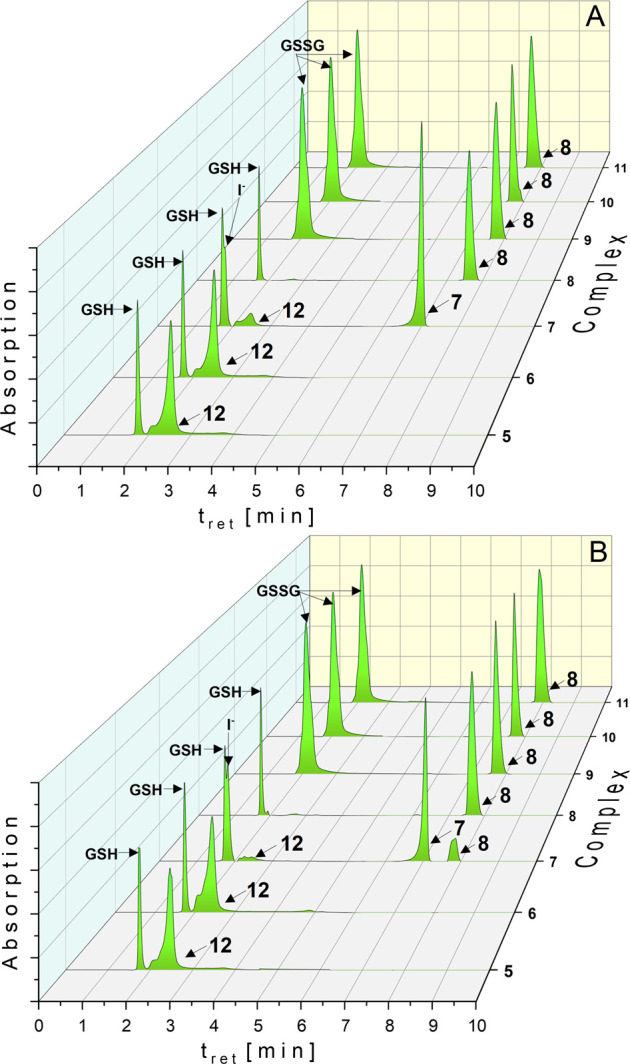

Figure 4.

HPLC chromatograms of 5–11 in the presence of 20 equiv of GSH (solution: ACN/water = 50/50 (v/v)) at t0h (A) and t24h (B). Complex concentration: 0.5 mM.

The used HPLC method allowed the discrimination of GSH from its oxidized form GSSG as well as 5–11 from the (NHC)Au(I)-GSH adduct 12.

The chlorido complex 5, as well as the bromido complex 6, reacted quantitatively with GSH in a substitution reaction. Already after 1.5 min (t0h, Figure 4A), only 12 was observed, without further degradation (t24h, Figure 4B). Redox reactions did not occur.

In contrast, GSH displaced iodide from 7 (→12) only in a proportion of 9.7% (t0h, Figure 4A), which decreased during 24 h to 4.7%, while 9.8% of 8 was formed (Figure 4B). Time-dependent analysis indicated that ligand scrambling of 7 started after 1 h. At the same time, the amount of 12 diminished (Figure S27).

GSH caused only substitution reactions, without reduction of Au(I) to Au(0). Other redox agents, too, did not affect the (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes. For instance, complex 5 incubated with sodium ascorbate or NADPH for 24 h showed only marginal ligand scrambling to 8 (ascorbate: 3.4%; NADPH: 5.6%, Figures S28 and S29). Neither reduction to gold(0), release of the NHC ligand, nor coordination to the gold(I) center occurred.

In the next step, the influence of reductive agents on the gold(III) complexes 9–11 was studied on the example of GSH.

Already the first contact (t0h) with GSH led to a quantitative reduction to 8 and formation of GSSG (Figure 4).

These results clearly demonstrates that (1) the reduction of [(NHC)2Au(III)X2]+ complexes is independent on the coordinated halides, and (2) the fast reduction to [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ implicates that 8 might be the biologically active form of 9–11, why examinations in the complete medium are necessary (see below).

The reactions of (NHC)gold(I)-X and [(NHC)2Au(III)X2]+ complexes with GSH were also investigated on the example of 5 and 11 by HR-MS.

Thereto, 5 and GSH were dissolved in MeOH/water mixture (50/50 (v/v)) to a 1/1 proportion and final complex concentration of 100 μM.

In addition to the expected reaction product 12 at m/z 780 (for confirmation via HCD fragmentation see Figure S30), also, higher adducts were detected after 24 h (Figure 5). The doubly charged ion with m/z 626 ((NHC)2Au2GSH) and the positive ion with m/z 1252 ((NHC)2Au2GS–) correspond to a T-shaped intermediate similar to that identified in the water-mediated scrambling reaction of mono-NHC-Au(I)-X complexes.25

Figure 5.

Full mass spectrum obtained from a mixture of 5 in MeOH and GSH in water (50/50, (v/v)) after 24 h.

HCD fragmentation of the ion m/z 626 (Figure S31) led among others to a species with m/z 749, which agrees with the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8, confirming the assumed structure with aurophilic interactions. Table S9 lists all identified ions. These findings document that 12 is capable for ligand scrambling.

Comparable HR-MS studies with 11 and GSH (proportion 1/10, complex conc. 100 μM) were performed. Already after an incubation time of 1.5 min, only signals of 8 (m/z 749), GSH (m/z 308), and GSSG (m/z 613) were observed in the solution, indicating a very fast reduction process (Figure S32).

To study the degradation in the complete cell culture medium, RPMI 1640 (without fetal calf serum (FCS)) was combined with the respective ACN solution of 5–11 in a 50/50 (v/v) ratio. Sample preparation and HPLC analysis were performed as described above. The results are depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

HPLC chromatograms of 5–11 (solution: ACN/RPMI 1640 = 50/50 (v/v)) at t0h (A) and t24h (B). Complex concentration: 0.5 mM.

As expected from the experiment in chloride containing solution, the bromido complex 6 immediately converted to the chlorido complex 5 (t0h, Figure 6A) and degraded subsequently comparable to 5 (Figure 6B). After 24 h of incubation, 5 only marginally reacted to the GSH-adduct 12 (5.1%) and the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 (6.2%).

The reduced transformation (compared to the direct reaction with GSH) might be the consequence of the high chloride concentration in the medium. To confirm this assumption, 5 was incubated in a control experiment with 20 equiv of GSH (as described above) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). At t0h, 65.7% of 12 was formed. The amount increased during 24 h to 68.0% of 12 and 2.1% of 8 appeared (Figure S33). These results points to an inhibitory effect of chloride on the substitution reaction of (NHC)gold(I)-Cl complexes.

The iodido complex 7 was more stable in the RPMI 1640 medium and transformed at t0h only by 14.3% to 5 and by 0.8% to 8. During 24 h, the amount of 5 remained constant, but 8 increased to 23.1%. No GSH-adduct 12 could be detected.

As expected from the reactivity studies, complex 8 was stable in RPMI 1640 during 24 h of incubation.

The gold(III) complexes 9–11 strongly degraded in the medium. Complex 9 was reduced immediately after contact with the medium to 8 by 5.0% and during 24 h by 36.3%.

In case of 10, additionally, a fast Br/Cl exchange took place. At t0h, 42.3% of 9 and 9.3% of 8 were formed. During 24 h, the amounts of gold(III) complexes 9 and 10 decreased to 18.2 and 10.7%, respectively, in favor to the gold(I) species 8 (71.1%). In contrast, the solution of 11 contained at t0h only the [(NHC)2Au(III)I2]+ complex, which then completely converted to 8 in the redox reaction with GSH within 8 h (Figure 6B and Figure S34).

In a final experiment, the influence of proteins on the degradation and free available (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes was studied on the example of the iodido complex 7.

The complex (conc. 30 μM) dissolved in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in the dark. Subsequently, the proteins were precipitated with ACN and the supernatant was dried by lyophilization. The remaining complexes were extracted from the lyophilizate with DCM. The organic layer was evaporated, and the residue was finally dissolved in 1 mL of ACN. This solution was then analyzed by HPLC as described above.

It is obvious from Figure 7 that, besides 7, the chlorido complex 5 and the cationic complex 8 were present as a free fraction. From the peak areas, the concentrations were calculated with 10.12 μM (5), 0.78 μM (7), and 2.14 μM (8). This means that about 50% of the complexes were protein-bound and were separated by protein precipitation with ACN.

Figure 7.

HPLC chromatogram of 7 after 4 h incubation in RPMI 1640 + 10% FCS (complex concentration: 30 μM), protein precipitation, and lyophilization.

In conclusion, the reactivity studies clearly demonstrate that (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes converted in the cell culture medium dependent on the bound halide.

The chlorido complex 5 was very stable in aqueous solution, while the bromido derivative 6 was rapidly and nearly quantitatively transformed to 5. In both cases, marginal ligand scrambling to the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ species 8 took place, whose participation on the biological activity cannot be excluded.

A more complicated degradation profile showed the iodido complex 7. Besides the initial complex 7, 5 and 8 were built at concentrations, which make their participation on the biological effects very likely.

The gold(III) complexes 9–11 were not stable in the medium. They undergo halide exchange reactions and reduction to 8.

The [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ species 8 was the most stable complex among the tested compounds without degradation in the cell culture medium.

Biological Activity

Effects against Wild-Type and Resistant Cancer Cells

In vitro cytotoxicity assays were performed to get an insight into the antitumor activity of the (NHC)gold complexes. Complexes 5–11, the established antitumor drug Cisplatin as well as Auranofin, used as a reference for a gold containing drug, were tested in different wild-type and corresponding resistant cancer cell lines. The influence on the metabolic activity was quantified in a modified MTT assay. It involves the conversion of the water-soluble yellow dye MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to an insoluble purple formazan by the action of mitochondrial reductase. Formazan is then solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the concentration is determined by optical density at 570 nm.

The complexes 5 and 6 were low active in the lung cancer cell line A549, the Taxol-resistant subclone A549-R, and chronic myelogenous leukemia(CML) cell line K562 and its Doxorubicin-resistant subclone K562-R (Table 1). The IC50 values of both complexes were higher than 10 μM. However, the complexes reduced the viability of human MCF-7 breast cancer cells and the Tamoxifen-resistant subline (MCF-7TamR) with IC50 = 4.54–5.76 μM (Table 1). The comparable results of both complexes might be the consequence of the degradation of 6 to 5 in the cell culture medium.

Table 1. Metabolic Activity in A549/A549-R, K562/K562-R, and MCF-7/MCF-7TamR Cells Determined in a Modified MTT Assay.

| metabolic

activity IC50a [μM] |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | A549 | A549-R | K562 | K562-R | MCF-7 | MCF-7TamR |

| 5 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | 5.76 ± 0.88 | 4.95 ± 0.39 |

| 6 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | 4.54 ± 0.52 | 4.64 ± 0.44 |

| 7 | 1.12 ± 0.17 | 1.21 ± 0.36 | 0.72 ± 0.30 | 1.53 ± 1.04 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 1.63 ± 0.79 |

| 8 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.26 | 1.79 ± 0.23 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| 9 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 1.43 ± 0.29 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.05 |

| 10 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 1.59 ± 0.30 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.18 |

| 11 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.26 | 2.26 ± 1.08 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.07 |

| Auranofin | 4.26 ± 0.45 | 4.42 ± 0.44 | 3.66 ± 0.27 | 3.75 ± 0.38 | 3.15 ± 0.36 | 1.14 ± 0.46 |

| Cisplatin | 6.67 ± 0.63 | 6.99 ± 0.57 | 7.91 ± 0.78 | 9.93 ± 0.77 | 7.18 ± 1.28 | 4.13 ± 0.59 |

The IC50 value represents the concentration causing a 50% decrease in metabolic activity after 72 h of incubation and is calculated as the mean ± SD of two or three independent experiments.

The higher activity in hormone-dependent breast cancer cells points to the carrier function of the 1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene moiety as related imidazoles were identified as drugs interfering with the estrogen receptor pathway.43,44 This finding will be evaluated more detailed in a forthcoming structure–activity relationship study.

In contrast, the iodido complex 7 showed high potency in A549/A549-R (IC50 = 1.12 and 1.21 μM) and K562/K562-R cell lines (IC50 = 0.72 and 1.53 μM) and distinctly higher cytotoxicity in MCF-7/MCF-7TamR cells (IC50 = 0.48 and 1.63 μM, Table 1), respectively).

The [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 was the derivative, which reduced the metabolic activity most effectively in the low nanomolar range, independent on the cell line used (IC50 = 0.14–1.79 μM, Table 1). The complex was 10- to 20-fold higher active than Cisplatin or Auranofin.

Complex 8 is the one with the highest stability, without transformation under cell culture conditions, why the effects can unequivocally be assigned to this species.

The gold(III) derivatives 9–11 (IC50 = 0.18–2.26 μM, Table 1) were comparably active as 8. Since it was demonstrated that GSH present in the medium reduces gold(III) to gold(I), it can be assumed that 9–11 are prodrugs and 8 was the active ingredient.

8 was also involved in the activity of 7. The latter is partially transformed in a ligand scrambling reaction to 8 and in a substitution reaction to 5 as discussed above. Therefore, it is very likely that the effects observed for 7 caused at least three compounds.

The complexes 5–11 were further submitted to an extended testing in various ovarian cancer cell lines (Table 2), since related derivatives showed good effects against A2780 ovarian cancer cells, especially Cisplatin-resistant subclones (A2780cis cells).27,32

Table 2. Metabolic Activity in A2780/A2780cis/A2780V-CSC, IGROV1/IGROV1-CSC Cells Determined in a Modified MTT Assay.

| metabolic activity IC50a [μM] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | A2780 | A2780V-CSC | A2780cis | IGROV1 | IGROV1-CSC |

| 5 | 9.45 ± 0.96 | 9.71 ± 1.20 | 4.08 ± 0.80 | 7.53 ± 1.90 | 9.18 ± 1.32 |

| 6 | 9.38 ± 0.80 | 8.28 ± 0.74 | 2.87 ± 0.33 | 5.78 ± 0.90 | 8.78 ± 0.60 |

| 7 | 1.43 ± 0.40 | 1.65 ± 1.23 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 1.94 ± 0.35 | 0.47 ± 0.13 |

| 8 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 1.04 ± 0.71 | 0.97 ± 0.66 |

| 9 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.70 ± 0.38 | 1.74 ± 0.19 |

| 10 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.19 | 1.29 ± 0.23 |

| 11 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 1.07 ± 0.21 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 1.28 ± 0.93 | 2.45 ± 0.97 |

| Cisplatin | 6.65 ± 1.42 | 4.88 ± 0.40 | 9.80 ± 0.64 | 2.84 ± 0.76 | 3.76 ± 0.40 |

The IC50 value represents the concentration causing a 50% decrease in metabolic activity after 72 h of incubation and is calculated as the mean ± SD of two or three independent experiments.

The cytotoxicity tests included besides the A2780/A2780cis cell lines also those enriched with cells with CSC characteristics (A2780V-CSC and IGROV1-CSC cells).45

CSCs are characterized by clonogenicity, asymmetric division, and high tumorigenicity and thus are related to drug resistance and tumor relapse in diverse cancers. Hence, novel inhibitors that eradicate CSCs are promising for mono or combination therapy of refractory and difficult-to-treat cancers.46

Auranofin served as a reference and showed a comparable activity in ovarian A2780/A2780cis cancer cells as already published.19,47

Compounds 5 and 6 were active with IC50 values of 6–9 μM in A2780, A2780V-CSC, IGROV1, and IGROV1-CSC cells and 3–6 μM in A2780cis cells.

Complex 7 showed significantly higher effects due to the transformation in the medium, with the highest cytotoxicity in A2780cis (IC50 = 0.40 μM) and IGROV1-CSC cells (IC50 = 0.47 μM).

The [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex 8 reduced the metabolic activity of A2780/A2780cis/A2780V-CSC cells with IC50 values in the range of 0.02–0.45 μM. It was slightly less active against IGROV1 (IC50 = 1.04 μM) and IGROV1-CSC cells (IC50 = 0.97 μM). Complexes 9–11 showed comparable effects as 8, indicating again that they act as prodrugs.

The data listed in Table 2 show that A2780cis cells were high-sensitive to 8 and 9–11, with IC50 = 0.02–0.10 μM. Cisplatin was 100- to 300-fold less active (IC50 = 9.80 μM). Therefore, it seems to be possible to circumvent Cisplatin-resistance with these compounds.

Against A2780 (IC50 = 0.18–0.29 μM) and A2780V-CSC (IC50 = 0.45–1.07 μM) cells, too, 8–11 were more active than Cisplatin (IC50 = 6.65 and 4.88 μM), which documents an obvious selectivity for the human ovarian adenocarcinoma.

Especially, the activity in the low nanomolar range against the Cisplatin-resistant subclones is of interest. The resistance of A2780cis cells is triggered by an elevated ability to repair Cisplatin-damaged DNA.48

In contrast to Cisplatin, which forms intrastrand cross-links at the DNA, the (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes 5–7 can only be mono-functionally bound to nucleobases. This could bypass the DNA repair system.

More difficult is the interpretation of the high cytotoxicity of 8 and its prodrugs 9–11. Complex 8 is inert against substitution reactions, and binding to bionucleophiles seems to be difficult. Nevertheless, Casini et al.49 identified the G-quadruplex DNA as binding partner of [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complexes. This might be true as mode of action of 8–11.

Further targets are recently discussed by Augello et al.11 for the 4-OCH3 derivatives of 6 and 8. Interestingly, although higher antiproliferative, the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ complex did not inhibit the thioredoxin reductase, the well-accepted target of (NHC)gold(I) complexes.16 Interference into other cellular pathways resulting in an increase of the intracellular ROS (reactive oxygen species) level, which in turn cause DNA damage, could also play an essential role.

These results clearly demonstrate that the complexes 7–11 are suitable for the treatment of cells with acquired and intrinsic resistance to common antitumor drugs. Especially, the high effects against CSC-enriched cell lines are noteworthy. Exceptionally, 7 was the most active complex against IGROV1-CSC cells.

Finally, it was evaluated in a preliminary experiment, whether the (NHC)Au(I)-GSH complex 12 possesses cytotoxic effects. It was incubated with A2780 cells and reduced the cell growth with IC50 = 15.9 μM, which is about 2-times higher than that of 5 and 6. Therefore, it is very likely that the GSH adduct is not part of the detoxification system of (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes. Detailed information will be published in a forthcoming paper.

Influence on Noncancerous SV-80 Cells

Finally, 5–11 were tested against the noncancerous lung fibroblast cell line SV-80 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Metabolic activity in noncancerous SV-80 lung fibroblast cells determined in a modified MTT assay and calculated as the mean of three independent experiments.

Compounds 5 and 6, reduced the metabolic activity only at a concentration of 10 μM to 64 and 20%, respectively, while the same effect was achieved with 7 at 5- to 10-fold lower concentrations (metabolic activity 1.5 μM: 77%). Much higher was the influence of the cationic complexes 8–11. A significant reduction of the metabolic activity was already detected at the lowest concentration used (metabolic activity at 0.4 μM: 20–30%).

Conclusions

Halido[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) and [bis(1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene)]dihalidogold(III) hexafluorophosphate (halido = chlorido, bromido, iodido) complexes were synthesized and characterized. Of particular interest was the reactivity of the complexes against components of the cell culture medium and the identification of reaction products. Additionally, the complexes were tested in wildtype and drug-resistant cancer cell lines for antimetabolic activity.

X-Ray structures of the (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes 5–7 showed the existence of dimeric units with Au(I)-Au(I) distances of 3.5 to 4.0 Å. Such aurophilic interactions can also be assumed in solution as a prerequisite for the observed ligand scrambling to the [(NHC)2Au(I)]+ species 8. Nucleophiles, such as chloride or GSH caused substitution reactions at (NHC)Au(I)-X, in case of the bromido complex 6 even quantitatively to 5 and 12.

An interaction with non-thiol containing amino acids was not evident. The role of GSH on the cytotoxicity of (NHC)Au(I)-X complexes is not fully elucidated. (NHC)Au(I)-GSH is partially formed in the medium. Interestingly, this reaction did not lead to an inactive species. (NHC)Au(I)-GSH caused antiproliferative effects in A2780 cells, only 2-fold less than 5.

Regarding the antiproliferative effects of 5–11, it must be mentioned that only 5 and 8 were stable against nucleophiles of the cell culture medium and the biological activity can be ascribed to these species.

The nearly identical activity of 5 and 6 in all cell lines (IC50 > 5 μM) resulted from the fast transformation of 6 to 5 in the cell culture medium, while partial ligand scrambling of 7 (→8) strongly increased the effects. The formed complex 8 was the most active compound in this study.

In the complete RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with FCS, protein binding must be taken into account. Quantification of 7 and its degradation products in RPMI 1640/FCS indicated that about 50% of the available complex 7 is located in the protein bound fraction.

The complexes 9–11 showed another reaction profile, without ligand scrambling, but with halide exchange reactions.

Most importantly, GSH reduced the gold(III) complexes to 8, indicating the prodrug character of the [(NHC)2Au(III)X2]+ complexes 9–11.

Complexes 8 and 9–11 possessed high cytotoxicity and reduced the viability of, e.g., A2780cis cells in the low nanomolar range. The circumvention of Cisplatin-resistance in ovarian carcinoma cells is therefore feasible with these complexes. Remarkably, the complexes also showed a promising potential to eradicate therapy-resistant CSCs.

Unfortunately, selectivity for tumor cells is not given for 5–11. The growth of SV80 fibroblasts was reduced to the same extent as tumor cells. Therefore, we will use in the following structure–activity relationship study the 1,3-dialkyl-4,5-diaryl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene as a new NHC carrier ligand to design effective (NHC)gold(I) complexes. The results will be presented in forthcoming papers.

Experimental Section

Chemical reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, BLDpharm, Fluka, Alfa Aesar, and Abcr) and were used without further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography was performed using Polygram SIL G/UV254 (Macherey-Nagel) plastic-backed plates (0.25 mm layer thickness) with fluorescent indicator and Merck TLC Silica gel 60 F254 aluminum-backed plates. The spots were visualized by UV light (254 nm). Column chromatography was done using silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063 mm). NMR spectra were from a Bruker Avance 4 Neo spectrometer (1H: 400 MHz, 13C: 101 MHz). The center of the solvent signal and the TMS signal were used as internal standards. Deuterated solvents purchased at Eurisotop were used as solvents. HPLC experiments were performed using a Shimadzu prominence HPLC with an autosampler SIL-20A HT, column oven CTO-10AS VP, degassers DGU-20A, detector SPD-M20A, and pumps LC-20 AD with a KNAUER Eurospher 100-5 C18, 250 × 4 mm column. The software used for data processing was LabSolutions. Mass spectra were from an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using direct infusion and electrospray ionization (ESI). MS data analysis was carried out with Xcalibur. The purity of all tested compounds was >95% as determined by HPLC analysis.

Synthesis and Characterization

Synthesis of the NHC-Ligand

4,5-Diphenyl-1H-imidazole (2)

Benzil (1) (2000 mg) was dissolved in 30 mL of conc. acetic acid together with 15 equiv of ammonium acetate (11.000 mg) and 1.1 equiv of paraformaldehyde (326 mg). The reaction mixture was then refluxed at 118 °C. After 5 h, the solution was neutralized dropwise with saturated aqueous sodium carbonate and extracted three times with ethyl acetate. Removal of the solvent and precipitation with toluene afforded compound 2 (1953 mg, yield 93%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.48 (s, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.20–7.49 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 135.62, 128.67, 128.16, 127.87, 127.06, 126.35.

1,3-Diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazolium Iodide (3)

To a stirred solution of 2 (1000 mg) and 1.1 equiv of sodium hydride (120 mg) in 30 mL of anhydrous ACN, 10 equiv of iodoethane (7081 mg, 3.65 mL) was applied and the reaction was stirred under an argon atmosphere at 82 °C for 24 h in the dark. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was taken up in DCM and water. The aqueous phase was separated and washed three times with 20 mL of DCM, and the collected organic phases were dried over sodium sulfate and evaporated in vacuo to yield compound 3 (1802 mg, yield 98%) as a brownish solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.50 (s, 1H), 7.53–7.39 (m, 10H), 4.11 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 1.32 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 135.70, 131.90, 131.42, 130.81, 129.69, 125.99, 43.46, 15.42.

1,3-Diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazolium Hexafluorophosphate (4)

To exchange the iodide counterion for hexafluorophosphate, 1000 mg of 3 was dissolved in 5 mL of MeOH and 5 equiv of potassium hexafluorophosphate (2276 mg) in 5 mL of water was added dropwise. The desired product (4) precipitated, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for another 24 h. The precipitate was sucked off and washed three times with 10 mL of water. After drying in high vacuum, pure compound 4 (989 mg, yield 95%) was obtained as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.48 (s, 1H), 7.53–7.39 (m, 10H), 4.11 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 135.49, 131.71, 131.14, 130.60, 129.49, 125.75, 43.20, 15.13.

General Synthesis of Chlorido/bromido(NHC)gold(I) Complexes

The hexafluorophosphate 4 (125 mg) was dissolved under an argon atmosphere and exclusion of light in an anhydrous DCM/MeOH (3 + 3 mL) mixture and supplemented with 0.7 equiv of silver(I)oxide (48 mg). The resulting suspension stirred overnight (12 h) at rt. Then, 5 equiv of lithium chloride/lithium bromide and 1.2 equiv of chlorido(dimethylsulfide)gold(I) (105 mg) were added to the reaction mixture. After stirring for additional 6 h and evaporating of the solvent, the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with DCM/MeOH = 9.8/0.2.

Chlorido[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (5)

Complex 5 was synthesized according to the general method with lithium chloride (63 mg) as a chloride source. After chromatography and recrystallization with n-pentane, the pure complex 5 (90 mg, yield 60%) was collected as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.36–7.33 (m, 6H), 7.22–7.19 (m, 4H), 4.21 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 1.32 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 169.23, 131.10, 130.49, 129.37, 128.87, 127.70, 44.40, 16.92. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – Cl + ACN]+ = 514.1557; found 514.1557, calculated for [M – Cl + N2]+ = 501.1353; found 501.1359. HPLC purity: 99.8%.

Bromido[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (6)

Complex 6 was synthesized according to the general method with lithium bromide (129 mg) as a bromide source. Off-white solid, 87 mg (yield 52%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.38–7.35 (m, 6H), 7.22–7.19 (m, 4H), 4.20 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 1.31 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 172.83, 131.04, 130.48, 129.36, 128.87, 127.71, 44.30, 16.93. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – Br + ACN]+ = 514.1557; found 514.1552. HPLC purity: 99.3%.

Iodido[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) (7)

5 (30 mg) dissolved in 5 mL of anhydrous acetone was stirred together with 10 equiv of sodium iodide (88 mg) for 5 min at rt. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was dissolved in DCM and subsequently filtered through a pad of Celite to separate the remaining salts (NaI/NaCl) from 7. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness, and the residue was recrystallized from n-pentane to yield 7 (31 mg, yield 88%) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.40–7.33 (m, 6H), 7.22–7.19 (m, 4H), 4.21 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 1.32 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H. 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 179.96, 131.92, 130.48, 129.34, 128.87, 127.73, 44.05, 16.96. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – I + ACN]+ = 514.1557; found 514.1548. HPLC purity: 99.8%.

Bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) Hexafluorophosphate (8)

6 (59 mg) together with 1 equiv of 4 (45 mg) and 2 equiv of potassium carbonate (29 mg) was dissolved in 5 mL of anhydrous acetone under an argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred for 72 h under protection from light. Subsequently, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (DCM/ethyl acetate = 1/1). Recrystallization from n-pentane yielded the pure complex 8 (77 mg, yield 87%) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.41–7.33 (m, 12H), 7.28–7.20 (m, 8H), 4.27 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 8H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 182.63, 131.82, 130.60, 129.43, 128.93, 127.47, 44.31, 17.37. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – PF6–]+ = 749.2918; found 749.2919. HPLC purity: 97.9%.

Synthesis of (NHC)gold(III) Complexes

Bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-yliden]dichloridogold(III) Hexafluorophosphate (9)

8 (30 mg) was dissolved in 6 mL of DCM, and 10 equiv of dichloroiodobenzene (99 mg) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 24 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was washed three times with 10 mL of diethyl ether and dried to yield the pure complex 9 (32 mg, yield 98%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.48–7.26 (m, 20H), 4.38 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 8H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 153.26, 133.82, 130.58, 130.19, 129.23, 126.05, 44.04, 16.12. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – PF6–]+ = 819.2296; found 819.2249. HPLC purity: 98.3%.

Bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]dibromidogold(III) Hexafluorophosphate (10)

To 30 mg of 8, 1.1 equiv of bromine (6 mg, 2 μL) was added under constant stirring to 6 mL of DCM at −30 °C. Cooling was maintained for 30 min. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was stirred for another 2 h without cooling. The workup was carried out in the same way as described for 9 and yielded pure 10 (33 mg, yield 94%) as an orange solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.48–7.27 (m, 20H), 4.35 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 8H), 1.45 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 149.99, 134.19, 130.61, 130.17, 129.21, 126.11, 44.24, 15.74. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – PF6–]+ = 907.1285; found 907.1305. HPLC purity: 99.7%.

Bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diphenyl-1H-imidazol-2-ylidene]diiodidogold(III) Hexafluorophosphate (11)

Complex 11 was synthesized according to the procedure described for 10 with the difference of using iodine (10 mg) instead of bromine. Red-orange solid, 37 mg (yield 94%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetonitrile-d3) δ 7.47–7.26 (m, 20H), 4.30 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 8H), 1.40 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetonitrile-d3) δ 142.84, 135.50, 131.70, 130.64, 129.51, 127.28, 45.04, 15.12. HR-MS m/z: calculated for [M – 2I, PF6–]+ = 749.2918; found 749.2872. HPLC purity: 99.1%.

HPLC Investigations

Experiments in ACN/water: 1.0 mM solutions of the respective complex were prepared in ACN and diluted with HPLC-grade water (50/50, (v/v)) containing the double-concentrated amount of respective amino acid (20 mM), GSH (20 mM), sodium ascorbate (20 mM), or NADPH (20 mM). As a chloride source, an aqueous solution of KCl 0.8 g/L and NaCl 12 g/L was used. In each case, a final complex concentration of 0.5 mM was achieved. The solutions were incubated for 24 h at rt. For the experiments with RPMI 1640, the aqueous phase was replaced by a cell culture medium.

Samples (20 μL each) were taken at appropriate time points (t = 0 (1.5 min), 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 8, 12, and 24 h) and analyzed with a Shimadzu prominence HPLC system. The mobile phase consisted of ACN (HPLC-grade) and water (HPLC-grade) with 0.1% TFA. To achieve a separation of the compounds, gradient elution from (70/30 (v/v) to 90/10 (v/v)) of ACN/water (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)) was used with a flow rate of 1 mL/min at an oven temperature of 35 °C. All solvents have been degassed before use. The injection volume was 20 μL, and the detection wavelength was set at 235 nm, to detect the gold complexes and the amino acids in the chromatogram. Each experiment was displayed with the program Origin Pro 2018 (Origin LabCorporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

ESI-MS Measurements of 5 or 11 with GSH

5 and 11, respectively, dissolved in MeOH were combined with an aqueous solution of GSH containing 0.2% formic acid, to get a 50/50 (v/v) solution with a complex concentration of 100 μM and a complex/GSH proportion of 1/1 (5) and 1/10 (11).

The mixtures were measured on an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using direct infusion and the HESI source in positive mode after 2 min and 24 h and analyzed with Xcalibur (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Determination of the FCS Influence on Stability of 7 in RPMI 1640

To 11 mL of RPMI 1640 including 10% FCS, 11 μL of a freshly prepared 3 mM DMF solution of 7 was added. The solution was then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in the dark. Proteins were precipitated with 33 mL of ACN. The mixture was cooled to −30 °C and stored for 2 h at −20 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was separated by centrifugation (3000 rpm), collected, and dried by lyophilization. The lyophilizate was extracted three times with 5 mL of DCM and finally dried under reduced pressure. The residue was taken up in 1 mL of ACN, and 30 μL was analyzed by the HPLC method described above. Peak area was used for quantification. The calibrations of 5, 7, and 8 were obtained by injecting 30 μL of the respective solution of pure substances in ACN at a concentration of 1–30 μM (R2 > 0.99).

Crystallography

A Bruker D8 Quest Kappa diffractometer equipped with a Photon 100 detector was used to collect the single-crystal intensity data. Monochromatized MoKα radiation was generated by an Incoatec microfocus X-ray tube (50 kV/1 mA power settings) in combination with a multilayer optic. The supplementary crystallographic data were deposited as CCDC 2180314-2180320 (5–11). Copies of the data can be obtained, free of charge, at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Biological Methods

Cell Lines

The ovarian carcinoma cell lines A2780 and A2780cis were kindly provided by the Department of Gynecology, Medical University Innsbruck. To maintain resistance, A2780cis cells were incubated every second week with Cisplatin (1 μM). The resistance of the A2780cis cells is caused by an increased ability to repair DNA damage mediated by cytogenetic abnormalities.48 The fibroblast cell line SV-80, the lung cancer cell lines A549 and A549-R, and the ovarian cancer cell lines IGROV1, IGROV1-CSC, and A2780V-CSC were kindly provided by the Department of Internal Medicine V, Medical University Innsbruck. A549-R cells are resistant against Paclitaxel (5 nM). The resistance was generated by cultivating the A549 cells with gradually increasing concentrations of Paclitaxel. IGROV1-CSC and A2780V-CSC (originally termed IGROV1 SP and A2780V SP) represent therapy resistant cell lines with an enriched proportion of cancer cells with stem cell characteristics.45 The CML cell line K562-R cells was originally described by Hui et al. as a Doxorubicin-resistant subclone of the K562 cell line (originally termed as KD225).50 K562-R cells are also resistant toward Imatinib, as we described in previous publications.51−54

The breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MCF-7TamR were purchased from DSMZ, German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany. To maintain Tamoxifen resistance, the MCF-7TamR cells were treated with Tamoxifen (1 μM) every two weeks.

The cell lines A2780, A2780cis, A2780V-CSC, SV-80, A549, A549-R, K562, K562-R, IGROV1, and IGROV1-CSC were cultivated in RPMI 1640 without phenol red (BioWhittaker, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA), supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM) and FCS (10%) (all from Invitrogen Corporation, Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere and fed/passaged twice weekly. The cell lines MCF-7 and MCF-7TamR were cultivated in DMEM without phenol red (PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) and supplemented with sodium pyruvate (100 mM) (PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) and FCS (10%) (Invitrogen Corporation, Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) under the same conditions as the other cell lines.

Analysis of Cell Growth Inhibition

Exponentially growing cells were seeded at a density of 1500 cells/well (A2780, A2780cis, A2780V-CSC, A549, and A549-R), 1750 cells/well (MCF-7 and MCF-7TamR), 2500 cells/well (IGROV1 and IGROV1-CSC), 3000 cells/well (SV-80), and 20,000 cells/well (K562 and K562-R), respectively, into clear flat-bottom 96-well plates in triplicates. After 24 h of incubation for adherent cell lines and 1 h of incubation for suspension cell lines (K562 and K562-R) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2/95% air), the compounds were added to reach the indicated concentrations, respectively. The indicated final concentrations of the compounds in the well are 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 μM for substances 5 and 6 and the references Cisplatin and Auranofin, as well as 1.5, 0.75, 0.375, 0.1875, 0.09375, and 0.046875 μM for substances 7–11. All stock solutions were prepared in DMF at a concentration of 10 mM and were then diluted with RPMI 1640, supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM) and FCS (10%), to the respective concentrations. After another 72 h of incubation, the cellular metabolic activity was measured employing a modified 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (EZ4U kit, Biomedica, Vienna, Austria) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The optical density of the particular medium was subtracted to exclude the unspecific staining caused by FCS containing medium. The values were calculated with Excel 2019 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) using nonlinear regression and decal logarithm of the inhibitor versus variable slope equation, while the top constraint was set to 100%.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACN

acetonitrile

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- CSC

cancer stem cells

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMF

dimethyl formamide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- equiv

equivalents

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HR-MS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- MeOH

methanol

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NHC

N-heterocyclic carbene

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PhICl2

dichloroiodobenzene

- ppm

parts per million

- RP

reversed phase

- rpm

rounds per minute

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- rt

room temperature

- TamR

Tamoxifen resistant

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- (v/v)

volume per volume.

Data Availability Statement

Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00589.

1H and 13C NMR spectra of 5–11; HPLC chromatograms of 5–11 recorded in ACN, 7 recorded in ACN/water in the presence of amino acids and GSH, 11 recorded in ACN/RPMI 1640, 5 recorded in ACN/PBS in the presence of GSH, and 5 recorded in ACN/water in the presence of NADPH or sodium ascorbate; HR-MS data of experiments with GSH and 5 or 11; ORTEP of 6, 7, and 10–11; crystallographic data of 5–11 (PDP IDs: 2180314 (5), 2180315 (6), 2180316 (7), 2180317 (8), 2180318 (9), 2180319 (10), 2180320 (11) (PDF)

Molecular formula strings of 5–11 with IC50 values in A549, A549-R, K562, K562-R, MCF-7, MCF-7TamR, A2780, A2780cis, A2780V-CSC, IGROV1, and IGROV1-CSC cell lines (CSV)

Author Contributions

# P.K. and A.S. contributed equally. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Tiroler Wissenschaftsförderung (TWF), project (F.45021/8-2022), as well as by the intramural funding program of the Medical University Innsbruck for young scientists MUI-START, project 2021-01-005.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Valente A.; Podolski-Renić A.; Poetsch I.; Filipović N.; López Ó.; Turel I.; Heffeter P. Metal- and Metalloid-based ompounds to Target and Reverse Cancer Multidrug Resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 58, 100778 10.1016/j.drup.2021.100778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott I.; Gust R. Non Platinum Metal Complexes as Anticancer Drugs. Arch. Pharm. 2007, 340, 117–126. 10.1002/ardp.200600151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust R.; Beck W.; Jaouen G.; Schönenberger H. Optimization of Cisplatin for the Treatment of Hormone Dependent Tumoral Diseases, a Review. Part 1: Use of Steroidal Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 2742–2759. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gust R.; Beck W.; Jaouen G.; Schönenberger H. Optimization of Cisplatin for the Treatment of Hormone Dependent Tumoral Diseases, a Review. Part 2: Use of Non-Steroidal Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 2780–2779. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucaciu R. L.; Hangan A. C.; Sevastre B.; Oprean L. S. Metallo-Drugs in Cancer Therapy: Past, Present and Future. Molecules 2022, 27, 6485. 10.3390/molecules27196485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. V.; Desai N. M.; Casari I.; Massi M.; Falasca M. Metal-based Antitumor Compounds: Beyond Cisplatin. Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 119–135. 10.4155/fmc-2018-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kean W. F.; Hart L.; Buchanan W. W. Auranofin. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1997, 36, 560–572. 10.1093/rheumatology/36.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porchia M.; Pellei M.; Marinelli M.; Tisato F.; Del Bello F.; Santini C. New Insights in Au-NHCs Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 709–746. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora M.; Gimeno M. C.; Visbal R. Recent Advances in Gold–NHC Complexes with Biological Properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 447–462. 10.1039/C8CS00570B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou T.; Lum C. T.; Lok C.-N.; Zhang J.-J.; Che C.-M. Chemical Biology of Anticancer Gold(iii) and Gold(i) Complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8786–8801. 10.1039/C5CS00132C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augello G.; Azzolina A.; Rossi F.; Prencipe F.; Mangiatordi G. F.; Saviano M.; Ronga L.; Cervello M.; Tesauro D. New Insights into the Behavior of NHC-Gold Complexes in Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 466. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdalbari F. H.; Telleria C. M. The Gold Complex Auranofin: New Perspectives for Cancer Therapy. Discov. Oncol. 2021, 12, 42. 10.1007/s12672-021-00439-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott I. On the Medicinal Chemistry of Gold Complexes as Anticancer Drugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1670–1681. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand B.; Casini A. A Golden Future in Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry: The Promise of Anticancer Gold Organometallic Compounds. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 4209–4219. 10.1039/C3DT52524D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti G.; Banditelli G.; Bonati F. Metal Derivatives of Azoles. 3. The Pyrazolato Anion (and Homologs) as a Mono- or Bidentate Ligand: Preparation and Reactivity of Tri-, Bi-, and Mononuclear Gold(I) Derivatives. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 658–663. 10.1021/ic50193a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y.; Ma X.; Chang X.; Liang Z.; Lv L.; Shan M.; Lu Q.; Wen Z.; Gust R.; Liu W. Recent Development of Gold(I) and Gold(III) Complexes as Therapeutic Agents for Cancer Diseases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5518–5556. 10.1039/d1cs00933h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corinti D.; Coletti C.; Re N.; Piccirillo S.; Giampà M.; Crestoni M. E.; Fornarini S. Hydrolysis of Cis- and Transplatin: Structure and Reactivity of the Aqua Complexes in a Solvent Free Environment. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 15877–15884. 10.1039/C7RA01182B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R. G.; Gray H. B.; Basolo F. Mechanism of Substitution Reactions of Complex Ions. XVI.1 Exchange Reactions of Platinum(II) Complexes in Various Solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 787–792. 10.1021/ja01489a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzfried S. K.; Kapitza P.; Gallati C. M.; Nindl A.; Cziferszky M.; Hermann M.; Wurst K.; Kircher B.; Gust R. Investigations on Reactivity, Stability and Biological Activity of Halido (NHC)gold(I) Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 1395–1406. 10.1039/D1DT03528B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omondi R. O.; Ojwach S. O.; Jaganyi D. Review of Comparative Studies of Cytotoxic Activities of Pt(II), Pd(II), Ru(II)/(III) and Au(III) Complexes, their Kinetics of Ligand Substitution Reactions and DNA/BSA Interactions. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 512, 119883 10.1016/j.ica.2020.119883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milutinović M. M.; Bogojeski J. V.; Klisurić O.; Scheurer A.; Elmroth S. K. C.; Bugarčić Ž. D. Synthesis and Structures of a Pincer-type Rhodium(iii) Complex: Reactivity Toward Biomolecules. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 15481–15491. 10.1039/C6DT02772E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corinti D.; Paciotti R.; Re N.; Coletti C.; Chiavarino B.; Crestoni M. E.; Fornarini S. Binding Motifs of Cisplatin Interaction with Simple Biomolecules and Aminoacid Targets Probed by IR Ion Spectroscopy. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 92, 3–13. 10.1515/pac-2019-0110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. D. Surrounded by Ligands: The Reactivity of Cisplatin in Cell Culture Medium. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 27, 691–694. 10.1007/s00775-022-01970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzfried S. K.; Koenig S. M. C.; Gallati C. M.; Gust R. Internal and External Influences on Stability and Ligand Exchange Reactions in Bromido[3-ethyl-4-aryl-5-(2-methoxypyridin-5-yl)-1-propyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 8546–8553. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzfried S. K.; Gallati C. M.; Cziferszky M.; Talmazan R. A.; Wurst K.; Liedl K. R.; Podewitz M.; Gust R. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Gold(I) Complexes: Mechanism of the Ligand Scrambling Reaction and Their Oxidation to Gold(III) in Aqueous Solutions. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 15312–15323. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Bensdorf K.; Proetto M.; Hagenbach A.; Abram U.; Gust R. Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vitro Studies of Bis[1,3-diethyl-4,5-diarylimidazol-2-ylidene]gold(I/III) Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3713–3724. 10.1021/jm3000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallati C. M.; Goetzfried S. K.; Ortmeier A.; Sagasser J.; Wurst K.; Hermann M.; Baecker D.; Kircher B.; Gust R. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity of Bis[3-ethyl-4-aryl-5-(2-methoxypyridin-5-yl)-1-propyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(i) Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 4270–4279. 10.1039/D0DT03902K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob C. H. G.; Dominelli B.; Hahn E. M.; Berghausen T. O.; Pinheiro T.; Marques F.; Reich R. M.; Correia J. D. G.; Kühn F. E. Antiproliferative Activity of Functionalized Histidine-derived Au(I) bis-NHC Complexes for Bioconjugation. Chem. – Asian J. 2020, 15, 2754–2762. 10.1002/asia.202000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S.; Li Y.; Lynch V.; Arumugam K.; Sessler J. L.; Arambula J. F. Expanding the Biological Utility of bis-NHC Gold(i) Complexes Through Post Synthetic Carbamate Conjugation. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 10627–10630. 10.1039/C9CC05635A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binacchi F.; Guarra F.; Cirri D.; Marzo T.; Pratesi A.; Messori L.; Gabbiani C.; Biver T. On the Different Mode of Action of Au(I)/Ag(I)-NHC Bis-Anthracenyl Complexes Towards Selected Target Biomolecules. Molecules 2020, 25, 5446. 10.3390/molecules25225446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran D.; Müller-Bunz H.; Bär S. I.; Schobert R.; Zhu X.; Tacke M. Novel Anticancer NHC*-Gold(I) Complexes Inspired by Lepidiline A. Molecules 2020, 25, 3474. 10.3390/molecules25153474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallati C. M.; Goetzfried S. K.; Ausserer M.; Sagasser J.; Plangger M.; Wurst K.; Hermann M.; Baecker D.; Kircher B.; Gust R. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity of Bromido[3-ethyl-4-aryl-5-(2-methoxypyridin-5-yl)-1-propyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-imidazol-2-ylidene]gold(i) Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 5471–5481. 10.1039/C9DT04824C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzorno J. Glutathione!. J. Integr. Med. 2014, 13, 8–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman H. J.; Zhang H.; Rinna A. Glutathione: Overview of its Protective Roles, Measurement, and Biosynthesis. Mol. Aspects Med. 2009, 30, 1–12. 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi M.; Bohm S.; Di Re F.; Oriana S.; Spatti G. B.; Tognella S.; Zunino F. Glutathione and Detoxification. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1990, 17, 203–208. 10.1016/0305-7372(90)90048-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacchioni G. A Not-So-Strong Bond. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 226–226. 10.1038/s41578-019-0094-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan K.; Tiwary B. K.; Hossain M.; Chakraborty R.; Nanda A. K. A Mechanistic Study of Carbonyl Activation under Solvent-Free Conditions: Evidence Drawn from the Synthesis of Imidazoles. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 10743–10749. 10.1039/C5RA16386B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Bensdorf K.; Proetto M.; Abram U.; Hagenbach A.; Gust R. NHC Gold Halide Complexes Derived from 4,5-Diarylimidazoles: Synthesis, Structural Analysis, and Pharmacological Investigations as Potential Antitumor Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8605–8615. 10.1021/jm201156x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scattolin T.; Nolan S. P. Synthetic Routes to Late Transition Metal–NHC Complexes. Trends Chem. 2020, 2, 721–736. 10.1016/j.trechm.2020.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bian M.; Fan R.; Jiang G.; Wang Y.; Lu Y.; Liu W. Halo and Pseudohalo Gold(I)–NHC Complexes Derived from 4,5-Diarylimidazoles with Excellent In Vitro and In Vivo Anticancer Activities Against HCC. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 9197–9211. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado A.; Bohnenberger J.; Oliva-Madrid M.-J.; Nun P.; Cordes D. B.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Nolan S. P. Synthesis of AuI- and AuIII-Bis(NHC) Complexes: Ligand Influence on Oxidative Addition to AuI Species. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4111–4122. 10.1002/ejic.201600791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh H. V.; Guo S.; Wu W. Detailed Structural, Spectroscopic, and Electrochemical Trends of Halido Mono- and Bis(NHC) Complexes of Au(I) and Au(III). Organometallics 2013, 32, 4591–4600. 10.1021/om400563e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gust R.; Keilitz R.; Schmidt K.; von Rauch M. Synthesis, Structural Evaluation, and Estrogen Receptor Interaction of 4,5-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)imidazoles. Arch. Pharm. 2002, 335, 463–471. 10.1002/ardp.200290000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust R.; Keilitz R.; Schmidt K.; von Rauch M. (4R,5S)/(4S,5R)-4,5-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-imidazolines: Ligands for the Estrogen Receptor with a Novel Binding Mode. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 3356–3365. 10.1021/jm020809h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesch M.; Zeimet A. G.; Reimer D.; Schmidt S.; Gastl G.; Parson W.; Spoeck F.; Hatina J.; Wolf D.; Sopper S. The Side Population of Ovarian Cancer Cells Defines a Heterogeneous Compartment Exhibiting Stem Cell Characteristics. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 7027–7039. 10.18632/oncotarget.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkar P. S. Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) Inhibitors in Oncology—A Promise for a Better Therapeutic Outcome: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 15279–15307. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini I.; Lapucci A.; Pratesi A.; Massai L.; Napoli C.; Perrone G.; Pinzani P.; Messori L.; Mini E.; Nobili S. Selection and Characterization of a Human Ovarian Cancer Cell Line Resistant to Auranofin. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 96062–96078. 10.18632/oncotarget.21708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. J.; Eastman A.; Bostick-Bruton F.; Reed E. Acquired Cisplatin Resistance in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells is Associated with Enhanced Repair of Cisplatin-DNA Lesions and Reduced Drug Accumulation. J. Clin. Invest. 1991, 87, 772–777. 10.1172/JCI115080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand B.; Stefan L.; Pirrotta M.; Monchaud D.; Bodio E.; Richard P.; Le Gendre P.; Warmerdam E.; de Jager M. H.; Groothuis G. M.; Picquet M. Caffeine-based Gold(I) N-Heterocyclic Carbenes as Possible Anticancer Agents: Synthesis and Biological Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2296–2303. 10.1021/ic403011h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui R. C. Y.; Francis R. E.; Guest S. K.; Costa J. R.; Gomes A. R.; Myatt S. S.; Brosens J. J.; Lam E. W. F. Doxorubicin Activates FOXO3a to Induce the Expression of Multidrug Resistance Gene ABCB1 (MDR1) in K562 Leukemic Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 670–678. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepf A. M.; Salcher S.; Hohn V.; Veider F.; Obexer P.; Gust R. Synthesis and Characterization of Telmisartan-Derived Cell Death Modulators to Circumvent Imatinib Resistance in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 1067–1077. 10.1002/cmdc.202000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepf A. M.; Salcher S.; Obexer P.; Gust R. Identification and Development of Non-Cytotoxic Cell Death Modulators: Impact of Sartans and Derivatives on PPARγ Activation and on Growth of Imatinib-Resistant Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 195, 112258 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepf A. M.; Salcher S.; Obexer P.; Gust R. Overcoming Imatinib Resistance in Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Cells Using Non-Cytotoxic Cell Death Modulators. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 185, 111748 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepf A. M.; Salcher S.; Obexer P.; Gust R. Tackling Resistance in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Novel Cell Death Modulators with Improved Efficacy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 216, 113285 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.